10 Identification, Cure and the End of Addiction

| Books - Drugs |

Drug Abuse

10 Identification, Cure and the End of Addiction

In the first edition of this book there was nothing about identifying addicts, because at the time this was not seen as a problem. By a kind of social tautology, the only 'addicts' in existence were the ones one knew about, and they, by definition, were the patients of doctors. Although everyone said that the Home Office figures for addicts, totalled from reports by medical, police, prison and probation services, were underestimates, no one had undertaken the detective work necessary to uncover the secret users. ,

That was true until the publication of Rathod and de Alarcân's excellent investigations19.20 into the addict population of Crawley (see p. 36 above). They, psychiatrists working in the local psychiatric service, suspected, quite rightly, that the eight known addicts in Crawley didn't represent the entire population. They developed and tested five ways of compiling a true list. These were: 1. The probation service, whose officers were asked to pass on the names and addresses of anyone known to be using drugs. 2. The police, who passed on the names of people convicted of possessing heroin, the names of those searched in the street on suspicion of possessing heroin, and the names of those associating with known drug users. 3. Known heroin users who were patients of the writers were encouraged to tell them about other users. 4. A survey was made of all hospitals and general practices in the area for patients between fifteen and twenty-five who had had jaundice (a frequent result of unsterile injections) within the last two years. 5. On the assumption that heroin users are likely to be pan-addicts and not necessarily too careful what they take, a search of all hospital casualty department records for people in this age group admitted with overdoses of hypnotics or stimulants.

This was in addition to the 'normal' detection methods of drug addicts presenting to their G.P.s and court referrals for psychiatric reports.

All this information was collated onto one card for each subject. A typical card would run: 'Jaundice, 12 December 1966; nam1 by heroin user 5 May 1967; named by second heroin user 5 June 1967; police suspect 23 September 1967; G.P. referral 5 October 1967; seen in outpatients' clinic 8 October 1967.'

Interestingly, they found that the two most productive screening methods were information from other heroin users, which produced first evidence on 46 people, and the jaundice survey, first evidence on 20. G.P. referrals produced first evidence on only 8 of 92 users. The casualty survey produced 15, police suspicions 30 convictions 4, and the probation service 2.

The same writers followed up this work with a study of clinical signs of heroin dependence, which included a useful investigation into the 'oddities of behaviour and appearance which [a group of twenty parents] had noticed in their children before the use of drugs cameo light'. These parents had noticed the following signs (the 'percentages refer to the number of I parents reporting each sign):

Poor appetite: 80%

No interest in personal appearance: 70%

Unexpected absences from home (to obtain supply): 65%

Spends long periods in his room: 65%

Sleeps out (loses motivation to come home when high): 65%

Slow and halting speech: 60%

Gives up organized activities: 60%

Receives and makes frequent phone calls (to check on supplies): 55%

Blood spotting on clothes (mainly pyjama tops and shirts): 50%

Litter in room or pockets: 45%

Stooped posture: 45%

Fully burnt matches lying around (e.g. floating in toilet) used to prepare the fix: 20%

Teaspoons lying around (used to prepare fix): 15%

'When the parents found out about their child's predicament and began to attend our groups, many of than became aware of changes in general behaviour — e.g one parent told us, "In the last two days his usual breakfast appetite has gone, he must be taking drugs again"; another said "The frequent telephone calls have started again". In both cases their suspicions were later confirmed.'

This paper goes on to distinguish the symptoms of addiction from those of other adolescent problems. Incipient schizophrenia produces many of the symptoms noted above, but doesn't lead to making new friends; depressions too, but again sufferers are unlikely to be dreamy, euphoric or spend nights out. Disappointing love affairs produce irritability and preoccupation. 'All these possibilities have to be kept in mind when considering dependence on drugs, otherwise parents may be alarmed unnecessarily. On the other hand, if many of these signs occur together, and there have been recent changes in general behaviour, drug dependence should be high on the list of differential diagnosis.'

Cure

The 'cure' of addiction presents two problems, one physical, and the other social and psychological. The first arises only with the truly addictive drugs — opiates and barbiturates — which produce physical changes and dependence in the body. Although a great deal is said about this physical aspect of drug cures, it is in fact a relatively minor matter. Taking heroin and the opiates first, the problem of reducing an addict's dosage to zero can be solved in several ways. One is simply to cut off his supplies, to let him go 'cold-turkey', and fight his way through the withdrawal as best he can. Though quick, and offering the advantage that he is too weak to run away until fairly over his physical dependence, this method is now considered too brutal for use in medical practice. Régimes for gradual withdrawal vary according to the institution and the doctor administering them. They divide again into those that employ a substitute drug, and those that do not. Much fuss is made over 'heroin cures', meaning drugs that can be substituted for heroin without producing further addiction— as heroin was at first substituted for Morphine — but it does not seem that they are anything more than a convenience, and whether they are used or not has no real bearing on the final outcome. In the American Public Health Hospitals at Fort Worth and Lexington, methadone — a synthetic and less active opiate — is given by mouth in decreasing doss; in other systems the actual drug of addiction is progressively reduced in quantity. At the same time vitamins and tranquillizers may be given, and sleeping pills at night, which may have to be continued for some months to combat the ex-addict's insomnia. In any event there is no need for the addict to feel more than the discomfort of a sharp dose of flu during a modern medically supervised withdrawal. In H.M. prisons the treatment followed is left to the discretion of the medical officer, but it is usual to withdraw drugs according to the general principles outlined above.1

Any addict who will stay, or can be kept, under supervision and without being able to get at drugs for ten days can be restored to a normal metabolic state. It may take another three months of rest, good food and exercise to put him back in reasonable physical condition. Medical science has gone this far; it has not begun to attack the problem of drug dependence.

As we have seen in earlier chapters, the person who is dependent on drugs — whether they are addictive or not — is the end result of many years of damaging pressures. He probably comes from a bad, cold home, he has no self-confidence, no belief in his own identity, no experience of normal living and normal satisfactions, and, on the contrary, powerful impressions of the pleasures to be got from drugs. The very first problem after withdrawal is that he has nothing to do all day, and no one to talk to.

As a habit takes hold, other interests lose importance to the user. Life telescopes down to junk, one fix and looking forward to the next, 'stashes' and 'scripts', 'spikes' and 'droppers'. The addict himself often feels that he is leading a normal life and that junk is incidental. He does not realize that he is just going through the motions in his non-junk activities.2

And again:

... it's like telling a man afflicted with infantile paralysis to run a hundred yards. Without the stuff Tom's face takes on a strained expression; as the effects of the last fix wear off all grace dies within him. He becomet a dead thing. For him, ordinary consciousness is like a slow desert at the centre of his being; his emptiness is suffocating. He tries to drink, to think of women, to remain interested, but his expression becomes shifty. The one vital coil in him is the bitter knowledge that he can choose to fix again. I have watched him. At the beginning he is over-confident. He laughs too much. But soon he falls silent and hovers restlessly at the edge of a conversation, as though he were waiting for the void of the drugless present to be miraculously filled. (What would you do all day if you didn't have to look for a fix?) He is like a child dying of boredom, waiting for promised relief, until his expression becomes sullen. Then when his face takes on a distasteful expression, I know he has decided to go and look for a fix.'

Whether he remains off drugs after withdrawal depends crucially on his morale and motivation, and these depend entirely on his relationship with his doctor. The successful addict curer has to combine the qualities of gaoler and wild-animal catcher, to be gentle yet more single-minded than the monomaniacs he has to deal with. One of the dozen London doctors who dealt with addicts before Treatment Centres started reports that she follows an elaborate preparatory routine before embarking on dose reduction: The addict is at first given unlimited drugs to establish confidence and binding ties. Then he is made to conform to a set dose, then to a reduced dose. At the same time he is helped and encouraged, even being lent money if necessary, to get a home, find a job, settle down, keep away from other addicts, and genetally to begin learning what ordinary life is about. Psychiatric treatment begins:

The goal ... is to correct as far as possible these personality difficulties, to give the patient a sense of security, self-reliance and self-confidence and a sense of responsibility towards himself, his family and friends, and towards the community, and to replace his sense of anxiety and insecurity with a sense of well-being.... At the same time it was made clear that insight was not enough; that a constructive attempt must be made to control and strengthen the weaknesses of a personality which had been led to disaster. Even those few young patients who had been led into taking drugs out of curiosity and through the influence of bad companions were made to realize that the danger was due to a personality disorder which must be rectified.'

Three hospitals in and around London accept addicts for treatment, but there seem to be few attempts made at adequate preparation before withdrawal, or even more important, at the intensive social support needed after withdrawal. The success rates are in. line with those reported from institutions in America and other parts of the world: 16 per cent free for seven years according to one writer,s or 10 per cent.6 The importance of strong character and motivation in the therapist is shown by the relatively higher success rates claimed by Anglican nuns who run a nursing home at Spelthorne St Mary's (near Egham in Surrey). This establishment accepts female addicts and alcoholics, who are encouraged to stay for some months in the community for rehabilitation after withdrawal. Because of their vocations and personal stability the nuns seem able to give considerable emotional support to their patients, and ex-patients often form very strong attachments to the place. At every weekend it is common to find one or two there on a visit, and at Christmas there are likely to be more visitors than patients. Apart from the hospitals that offer out-patient treatment centres and the three or so that accept addicts as in-patients, there is a number of half-way houses, day centres, and other more or less loose organizations designed to help and support addicts. These wax and wane with the enthusiasms of their promoters, but cannot be said to offer together more than a palliative to the basic problems of drug dependence.

The comparative rarity of British addicts in the past has meant that there was neither need nor material for the elaborate comparative studies of cure methods and successes that are necessary before any realistic policy towards addiction can be devised. As usual, we have to turn to the superior resources of the United States.

Since the typical American addict is now a twenty-year-old Negro boy living in a big city7 their experience can be suggestive only. It has been mentioned that the cure and study of addiction is regarded as a Federal responsibility., The two public-health hospitals (see p. 31) are open to voluntary and prison patients. An attempt is made to rehabilitate both classes by work in the hospital; voluntary patients are expected to stay for a minimum of five months at Lexington. About one patient in six is a prisoner. A follow-up over twelve years of a hundred addicts discharged from treatment at Lexington in 1952-3 shows several interesting facts about the relative effectiveness of different régimes. Of this hundred, many were in Lexington more than once either as voluntary patients or prisoners in the years after 1953. There were altogether 270 voluntary admissions, but only eleven times did these patients stay off drugs for more than a year after treatment. Almost as many did as well themselves, going cold-turkey at home. The most effective treatment turned out to be a prison sentence of more than eight months followed by more than a year's parole — but the prison sentence without parole was hardly more effective than voluntary treatment:

... the likelihood that significant abstinence would occur after prolonged involuntary imprisonment followed by prolonged involuntary supervision was fifteen times greater than after voluntary hospitalization.

And long hospitalization, produced most often by court pressure, produced longer abstinence than short hospitalization.

The importance of coercion in treating addicts seems widely underestimated. The author of this paper says:

The findings of this paper suggest that addicts may differ from most psychiatric patients.... In general psychiatric patients cannot be ordered to give up symptoms, and prolonged hospitalization drives patients towards increased dependence rather than maturity....

Addicts tolerate anxiety poorly; they 'act out'; they often engage in self-destructive behaviour that is not consciously realized as detrimental. Individuals with such defences often do not experience a strong conscious desire to change. ...

Psychotherapy is most often directed towards relieving or correcting unrewarding behaviour that has arisen out of too much, or the wrong sort of training. The delinquent addict, however, has often encountered too little consistent concern from authority rather than too much or the wrong sort. The professional permissiveness of the psychiatrist may , seem to threaten the addict's immature efforts to control his impulsa. Both at Lexington and at the Riverside Hospital in New York, patients not uncommonly ask for more controls, not fewer. A ithe same time there is little to suggest that punishment per se either deters or benefits the addict . . .9 He needs someone to care when he is honest and independent.st

Addicts are notoriously resistant to ordinary psychotherapy. One way of looking at this is to observe that analysis depends on communication, on the patient's acceptance of the therapist as a real human being who can have a real effect on him. But the addict's whole life is organized to remove any dependence on humanity; given his drugs, he is self-sufficient, able to generate his own satisfactions and guilts and to live a rich emotional life

independent of the outside world. He therefore has no motives for communication when things are going well; when he does ( present himself for treatment it is often not because he wants to , be cured of addiction, but because his addiction is not working as it should.$ He is a two-time loser who wants to get back to being a one-time loser; not to take the much more perilous step to being an unloser. 'The ordinary psychiatric patient is like a burr, offering many hooks to the world and the therapist — often too many; the therapist's best strategy is to stand still and let his patient attach himself as he will. But the addict is like a nut; smooth with a thick armour. The only hook he offers is his need for drugs, and that can be satisfied in a number of ways. To reach the addict, his shell must be cracked. We might guess that it would be necessary to counter the coercion of opiates with the coercion of therapy; it is noticeable that those London doctors who treat addicts often have strong, obdurate personalities,9 in contrast to the majority of psychiatrists, and that their writings often show authoritarian tones — for example the writer quoted above and on p. 143.

Another successful American treatment centre, Synanon, an informal self-help community of addicts and ex-addicts, also seems to rely on force for its operation. The organization was founded in 1958 by an ex-alcoholic member of Alcoholics Anonymous. In 1966 it had 450 members. An addict who wishes to join first has to withdraw cold-turkey as an earnest of his good faith. He is then required to live in the community for a minimum of two years. The central features of the treatment are the seminars — mispronounced `synanons' by an early illiterate member — where the members meet in groups of eight or twelve for one and a half hours three times a week and subject each other to the most searching and vicious criticism, abuse and ridicule. The members of each seminar are rotated so that all the community come under fire from one another. Since it is one of the most characteristic personality problems of addicts that they cannot bear disparagement, this daily discovery that one can be criticized and still live on amicable terms with one's attackers must be a most salutary lesson. As well as this cathartic ` gut ' experience, the members have a positive frame of society to live in that also deeply understands their problems. They work, and ate paid a small amount of pocket money. They have the prospect of rising to the Board of Management. People who seem not to be benefiting from the community are given the choice of expulsion or trial by their peers. If they choose trial and are found guilty the men have their heads shaved; women have to wear a placard round their necks: 'I am a returnee from the twilight zone.' Desperate appliances relieve desperate diseases; Synanon has the motto `Hang Tough' and claims a success rate of fifty per moo

Daytop (Drug Addicts Treated On Probation) Village is an offspring of Synanon, with much the same organization. In 1967 it had a membership of ninety people, all ex-addicts. It understands the problems of the addicts' personality and takes a strong line with them. Barry Sugarman, describing Daytop in New Society,21 writes:

In very forcefid terms the entexing addict is told by senior members of Daytop that he is responsible for what he has done and that be 'cannot slough it off on unloving parents, negligent teachers, a corrupt society or any of the usual culprits. He decided to take dope and to steal and lie to get the money for it. He is also told that the reason he is an addict is because he is a child in terms of character and emotional development. Therefore they will treat him like a child at first: he must obey all the many rules of the house and all the decisions of the senior members without question. He may not leave the house, write letters, make phone calls, have visitors: he must perform the tasks assigned to him which at first will be the most menial household cleaning chores: cooking pots, floors, lavatories.

Another variant of the basic Synanon idea, but apparently more democratic in its organization, is found in the Phoenix Houses of New York. They claim a success rate of 80 per cent, and one opened in London under the wing of the Maudsley Hospital in 1970.

A fourth regime, which also uses cured addicts, backed by the sanctions of the courts, to wrestle with the uncured is New York State's programme under which addicts convicted of any crime can be committed to a clinic for up to five years. The system was developed in Puerto Rico by Dr Efran Ramirez.

In the light of these views, the Brain Committee's second report reads curiously:

Para. 24... we are mindful of the obstinacy of some addicts and the likelihood that some of them will not attend a treatment centre. Since compulsory treatment meets with little success [author's italics) there is little that can be done for these people beyond restricting the possibility of illicit supplies. Others may want to break off treatment after they have embarked on it. This may be a short-lived feature caused by the discomfort of the withdrawal symptoms. We think that the staff of a treatment centre should have powers to enable them compulsorily to detain such a patient during such a crisis. This we appreciate would require legislation.11

To withdraw an addict, even forcibly, but then to leave him virtually on his own, is as useful as pulling a broken leg straight, and then expecting its owner to walk away. The Brain Committee realized that 'the situation would in our view be greatly improved 148

if there were proper facilities for long-term rehabilitation, both psythological and physical, in the treatment centres and elsewhere. To go into more detail about this would be outside our term of reference . ..' (para. 25). All the material discussed above suggests that something much more drastic is needed; how this is to be achieved without alienating addicts and creating an even more virulent sub-culture is discussed in the next chapter.

An interesting new approach to the cure of heroin addicts is simply to transfer them to another, slower acting drug. No attempt is made to wean them from drugs altogether, but because the substitute drug that is often used, methadone, has a span of 24-35 hours as against heroin's 8 hours, their lives are transformed. Instead of being constantly busy (see p. 46) they now have time to work, eat and live something of a family life. Also because tolerance to methadone produces cross tolerance to heroin the ex-addict can get no 'high' however much heroin he takes. He gets his substitute from a clinic, and so it is possible to break his contacts with the drug sub-culture. Dole and Nyswander in New York have 800 addicts, all with four years' or more experience of main-lining and several attempts at cures, on this regime. The treatment begins with six weeks in hospital getting rested up, assessed and transferred to methadone. The patients are given the largest daily dose that doesn't make them sleepy — this prevents escalation onto heroin. After this they live out, helped by massive psychiatric and social care, go to a clinic every day for their dose of methadone and leave a urine sample as a check against other drug use. This lasts a year. In the third phase, when they have settled down as functioning members of society, they go once a week to get their doses. It is accepted that they will probably never be able to do without drugs, but in this they are like diabetics. It doesn't much matter.

Acupuncture, which is said to cure almost any disease, is also reported to be effective against heroin addiction. A treatment centre in Kowloon claims to have cured 600 addicts by passing a 125Hz, 5V electric wave through the conchae of their ears.23 (I tried it, without perceiving any effect, but then, I am not an addict.) An English doctor involved in the experiments plans to set up a-unit here to continue the worlc.24 But before one concludes that the addiction problem is solved, it might be as well to remember that, as for U.S. conscripts in Vietnam (p. 34), life for the average Chinese in overcrowded Hong Kong is so tiresome that, even in the absence of fundamental psychic predisposition, heroin addiction may be an attractive strategy for dealing with it. British addicts probably need the drug much more and are that much harder to cure.

So far this chapter has dealt with opiate addiction. Much the same techniques are used in withdrawing barbiturates, except that, because of the risk of convulsions and possible death, the daily redaction must be made smaller and the period of reduction extended to three weeks or more. The patient should never be allowed to walk about unattended, and the doctor should be constantly ready to give a holding dose to prevent withdrawaLls The subsequent problems are presumably the same.

Untreated Addiction

If an addict is not cured - and few are - one can say with some certainty that sooner or later he will either give up drugs or die. But the morbidity of drugs is uncertain; numbers are too few to calculate death and suicide rates accurately, even if the population at risk were known.

A survey by Bewley of the 507 heroin addicts known to the Home Office between 1954 and 1964 shows, in spite of the fact that there were seven times as many at the end of the decade as there had been at the beginning, a curiously constant rate of death at about two a year.11 This is probably explained by the youth of new addicts; so far we can draw no useful conclusions about the morbidity of heroin from our native experience. In America a recent study followed up Kentucky addicts discharged from Lexington between 1935 and 1959. (The average age of these patients on discharge was forty-two and they conformed to the old or southern pattern of addiction (see p. 31); in England we have something nearer the northern pattern, so these results must be read with some caution). The death-rate for male addicts over twenty-five was 2.7 times that for normals; for females it hardly differed from nomials14- another pointer to the weaker sex. In Formosa between 1901 and 1935 the death-rate for licensed opium addicts was also 2.7 times that for the rest of the population.15 This is a fairly impressive morbidity, contributed to by disease, murder, suicide, accidents; but figures of this sort can give no indication whether it is caused by drug use, or whether drug use, as it were, selected a particularly weak population which is unusually susceptible to the ills of this world. It is even conceivable that addicts might die quicker if they were not calmed and immobilized for a large part of their lives. In fact this may positively contribute to addicts' longevity. A recent government study in America showed that although heroin addicts drove nearly twice as many miles a year as the ordinary American (18,000 miles as against 10,000), mostly in order to get their drugs, they had half as many car accidents, even though they would almost all make the return journey in a state of euphoria. The moral is that calm saves lives on the road, even if it is pharmacological.

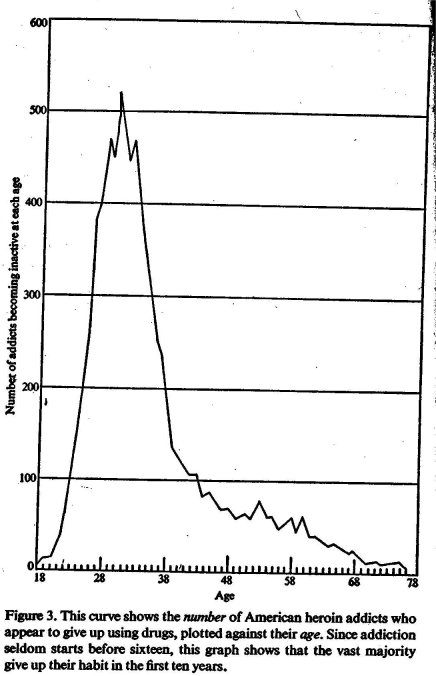

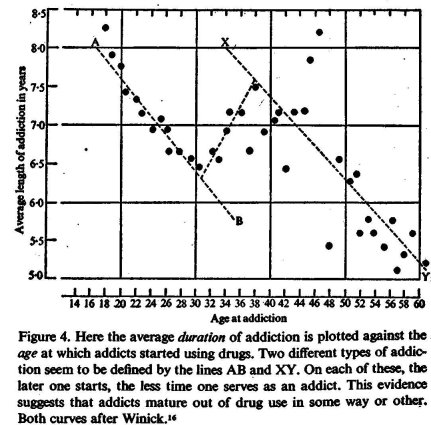

It is commonly thought that addiction to heroin ends inevitably in the addict's dissolution and death. It is not impossible that this is folk-lore rather than fact. The evolution of the addict's relationship with opiates, and its possibilities as a self-limiting process, are explored in two important papers by Winidc. He concludes intriguingly that for two thirds of addicts the use of opiates is a process that lasts for a comparatively short part of their lives. He finds, on examining the records held by the Federal Bureau of Narcotics of 7,234 addicts who had been active in 1955 and had not been reported by 1960, that the average length of addiction is 8 -6 years. Analysis showed that addiction lasted on the average from the early twenties to about thirty-five. The graph reproduced here, Figure 3, shows that a large number of addicts drop out after a very short period of use. An even more interesting curve, Figure 4, shows the relationship between the length of addiction and the age at which addiction begins. Cases whose addiction lasted more than sixteen years have been omitted; but forthe majority of addicts it appears that the duration of drug use is very simply related to the age of starting. The earlier you start, the longer you go on. It also suggests that there are two great groups of addicts: the 'adolescent' and the `middle-aged' - perhaps corresponding to the northern and southern patterns of addiction. The decrease in duration of addiction with later starting is extremely consistent, with a correlation of -.95 on the adolescent line, and -80 on the other. The points in between turn out to be averages between the two. The curves are so regular that Winick deduces simple formulae to predict the probable length of an individual's addiction:

If L = length of addiction and a = age

for those aged between 19 and 35

L= 10.09 - 0.126a

for those aged between 38 and 60 L= 11 .58 — 0.107a

One hopes that such regularity shows more than happy mathematical neatness, and proclaims a buried natural law. Winick supposes that this dropping out is the result of a process of maturing; that the earlier in each group an addict begins drug use, the more intense his problems are and the longer it takes him to grow out of them. The two ages from which the longest periods of addiction are likely are 18 and 37, both ages of greater stress for American men. He points out that at 18 the adolescent is confronted with the problems of deciding what sort of person he is; at 37 the man is faced with accepting what he has become. At the one age decisions must be made; at the other they have become irrelevant. He also points out that the curve in Figure 3 is identical in shape and distribution to the drop-out curve for psychotics, and very similar to that for recidivism among juvenile delinquents. It is possible that drugs, delinquency, psychosis are different methods of dealing with the same problems.16 But before we follow this line of thought, it is necessary to consider some criticism of Winick's work. There are two major assumptions: first, that an addict inevitably appears in the Bureau's file, as it claims, within five years of beginning drug use — there is no independent evidence in support of this; second, that non-appearance in the file means non-addiction.

At first glance, one might suppose that the high death-rates reported by O'Donnell and Tu would imply that all the drop-outs were in fact dead. But if one works backwards from Winick's survivors, using a death-rate 2.7 times the normal, one finds that his 4,000-odd addicts would, on this assumption, be the remnants of more initial users than the entire population of the U.S.A.

A follow-up of Puerto Rican opiate addicts in New York designed to test the maturation theory found that two thirds were still addicted, and that their drug use had tended to increase over the years. But on the other hand the rest had become abstinent, bad given up their criminal behaviour and had become reasonably productive citizens. About half were steadily employed and 90 per cent had not been arrested in the previous three years. The authors of this paper conclude:

It appears, then, that two major patterns exist with respect to the life course of opiate addiction in the United States. In one instance the addict becomes increasingly enmeshed in a non-productive or criminal career as his dependence on opiates increases into adult years. In the second case, the addict terminate; his drug-centred way of life and assumes, or re-establishes, a legitimate role in society. In this latter sense, it may be said that some one third of opiate addicts mature out of their dependence on drugs.22

If, after a certain period of addiction, the criminal and 'straight' ways of life compete for addicts, that would be another excellent reason why we should try to avoid driving drug use any further underground.

It must of course be remembered in attempting to apply these results to our experience, that few American addicts actually have access to any quantity of opiates, and that few in consequence have well-developed physical habits. It would perhaps be more accurate to say that most American addicts are no more than drug dependent. On the other hand English addicts, supplied with pure heroin, are able to build up really massive habits, and have their freedom of action very much reduced (see p. 173 below). But it is not uncommon for users of up to a grain a day in England to give their habit up. In the course of my own casual inquiries I was told of nine who had done so.

There is obviously not enough evidence to say with any certainty whether addicts use opiates for a while, and give them up when their emotional needs have passed; or whether they are grabbed and held, unwilling, by the drug. More research is essential; here we can only speculate on the consequences of Winick's interpretation.

One wonders, then, whether it is any use trying to 'cure' addicts simply by withdrawal, before they are ripe to give up drugs. It is possible that the normal 10 per cent cure rate for this method is due simply to people who would have ended their addiction anyway. It may even be harmful in certain cases to prevent the addict using heroin. We are so accustomed to consider drugs as unmitigated evils that it is worth rehearsing the argument leading to this conclusion.

1. Some pre-addicts (see p. 48) sound very like some young pre-schizophrenics described by Laing. Both groups were 'good' — i.e. passive — babies, often coming from homes that were materially not too badly off, both had strong but ambivalent relationships with their mothers, but ineffective fathers, both showed extremely plastic personalities.

2. Laing suggests that schizophrenia is the rest of a long attempt to evade deep anxiety, guilt and insecurity caused by the individual's failure to conceive of himself as a real, solid human being. He builds a false and variable personality front; he pretends to behave as people seem to want him to. Eventually the vacuum inside this shield becomes so large that the individual is cut off from reality and becomes mad.17

3. Heroin (see p. 21) is a specific against anxiety and painful emotions.

4. It is possible that the sort of person who uses heroin to obliterate his worries might otherwise. embark on the schizo- . phrenic's manoeuvres to avoid them.

5. Winick's work suggests that the heroin addict is likely to mature out of addiction as his instinctual drives die down, as the social pressures on him lessen, and Perhaps — since he is relieved of tension by the drug — as he completes the learning processes he could not in childhood.

6. The schizophrenic, once his disease has been acute for more than a year, is likely to suffer irreversible damage, and is — in the present state of psychiatry — incurable.

7. Perhaps it is better that he should be a drug addict for nine years or so, with at least the chance of some social function during this time, and a two to three chance of eventual recovery, than to be mad for a lifetime.

8. It may be possible that premature withdrawal from drugs re-exposes the addict to schizophrenia.

Laing writes, in a letter to the author,

From my own clinical practice, I have had the impression on a number of occasions that the use of heroin, might be forestalling a schizophrenic-like psychosis. For some people heroin seems to enable them to step from the whirling periphery of the gyroscope, as it were, nearer to the still centre within themselves;

and he suggests the usefulpess of surveys to discover if the use of heroin were less among schizophrenics than among the population at large, and if the incidence of schizophrenia were less among addicts.

In the present state of public opinion it would require some hardihood in a psychiatrist to addict his adolescent schizophrenic patients. The nearest reference in the literature seems to be the already quoted account of opium use to pacify violent insane criminals in nineteenth-century America.18 Opium is also said to be given to delinquent children in Formosa, who subsequently grow out of both habits.

*success of prolonged imprisonment in treating the addicts reported was due simply to keeping them in contact with therapy.

t During my interview with the author of the paper quoted on p. 139 n.4 an ix-addict who had been out of treatment for some years rang to tell her he was a father. His son was barely an hour old. `Then,' she said, that's the sort of relationship you've got to have to help addicts.'

$ 1 owe this idea to Dr Salomon Resnik.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|