3 CHALLENGES AND CHOICES FOR VICTORIA

| Reports - Drugs and our Community |

Drug Abuse

3 CHALLENGES AND CHOICES FOR VICTORIA

3.1 Introduction

The significant information and facts about illicit drugs that have informed Council's investigations are outlined in chapter 2.

Council's terms of reference required it to provide the State Government with recommendations regarding the response that should be made to illicit drug use in the community. Council has reached conclusions about the most appropriate strategy, and this chapter outlines the major issues considered and the rationale for Council's recommendations.

As a result of its investigations, Council has many significant concerns about illicit drug use in Victoria. These concerns focus on the harmful effects that drugs can have on the users, their families, friends and the community. More broadly, the Council is concerned that as a community we have a poor understanding of the impact that drugs have on society and the mixed consequences that their legal status generate.

The drugs under consideration in this inquiry are illegal. Licit drugs are available but are subject to varying levels of regulation and restriction. The differing legal response to drugs is a result of complex social and political forces not a statement about the intrinsic status of these drugs. The community is increasingly aware of the risks of misuse of drugs and has accepted greater regulation when dangers are clear. The section of this chapter on the law outlines and assesses a range of legal options.

Reducing drug use and misuse is critical in the light of Council's concerns about the impact of drugs. Prohibition can contribute by containing supply and reducing demand. A wide range of other strategies also prevent use and misuse and deserve attention. Important among these options are education and information strategies. In this area, Victoria is well placed because of its successful health promotion and education strategies, particularly in relation to alcohol and tobacco.

Providing support and treatment to people with serious drug use problems may prevent the development of further problems and will, in some instances, reduce use. Effective support and treatment must be flexible to respond to the diverse needs and situations of drug users. Treatment services need to focus on those with serious problems, and to respond to the harms produced and the context in which misuse occurs.

Since 1985, and particularly since effective responses were developed to HIV/AIDS, Australia has pursued a drug policy goal of harm minimisation. Council believes available evidence lends strong support to current Victorian and Australian approaches. None of the evidence received by Council has argued that there is a set of policies or strategies capable of eliminating drug use from our society in the foreseeable future. On the contrary, considerable concern has been expressed about the social causes of drug use and the likelihood that trends will be towards increased rather than decreased use.

Victoria's response to illicit drugs requires clear objectives that enable evaluation of existing activity and assessment of the likely impact of alternative approaches. The objectives need to be framed in the knowledge that the health consequences of misuse are substantial and that any law enforcement, prevention and treatment approach can have positive and unintended negative consequences.

Council believes the objectives for Victoria's response to drugs should be:

• Minimising the harms caused by the misuse of psychoactive drugs.

• Minimising the use of psychoactive drugs.

Chapter 2 provided a brief description of what is meant by harm minimisation (2.4). The overall objectives through which minimisation of drug-related harms are to be achieved have been spelt out by the National Campaign Against Drug Abuse (NCADA—now the National Drug Strategy) as:

• Promoting greater awareness and participation by the Australian community in confronting the problems of drug abuse.

• Achieving conditions and promoting attitudes whereby the use of illegal drugs is less attractive and a more responsible attitude exists toward those drugs and substances which are both legal and readily available.

• Improving both the quantity and quality of service provided for the casualties of drug abuse.

• Directing firm and effective law enforcement efforts at combating drug trafficking, with particular attention to those who control, direct and finance such activities.

• Supporting international efforts to control the production and distribution of illegal drugs.

• Seeking to maintain, as far as possible, a common approach throughout Australia to the control of drug use and abuse.

The Council had eleven weeks to conduct its inquiries. It has had the benefit of input from written submissions, public hearings, specialist hearings and discussions with experts from Australia and overseas. Approaches that will improve Victoria's approach to illicit drugs have been distilled from these extensive and generous contributions.

Material presented in this report raises a wide range of policy and operational issues. While Council has developed a strategy that underpins its recommendations, it acknowledges that many matters require further consideration, informed public debate and careful reform.

Council has attempted to develop an approach to Victoria's drug problems that, above all else, minimises the harm caused by misuse. This chapter provides the building blocks that give substance to Council's aspirations.

3.2 Current Knowledge

Council heard many inaccurate, false, and misleading assertions during its investigations. Illicit drugs and their effect on the community, and especially on the young, seem to promote views that are not always well grounded in factual information. This tendency is not confined to the general public as many people claiming to be expert in the area of illicit drugs are not always well-informed.

It is likely that the lack of well-informed public debate about illicit drugs is in part due to the fear they inspire in the community, their low prevalence relative to other drugs such as alcohol and tobacco and a lack of concerted public education.

Community understanding of the consequences of alcohol and tobacco misuse is relatively high. This level of understanding probably results from the extensive public education efforts made in recent years. The same does not exist for illicit drugs. While it is fortunate that use of illicit drugs, other than cannabis, is not widespread, efforts to provide the community with information have been limited, partly because of their illegal status. Prohibition has not helped to engage the community in efforts to reduce the harms of illicit drugs or reduce overall usage.

There are many important gaps in the data required to confidently formulate policy, design programs, and monitor service effectiveness. This has affected the shape of proposals put by Council. Qualifications have been placed on much of the data included in chapter 2. Examples of problems are:

• Information on the level of use, particularly dependent and problematic use, is limited and almost certainly understates the position. The data is collected through small-scale household surveys (National and Victorian Household Surveys). Such surveys, because of the nature of the sample, are likely to underestimate the numbers using illicit drugs (Sutton et al, 1995).

- Very few of the preventive and educational initiatives that have been undertaken have been subject to critical evaluation. Some of the completed evaluations were not available to Council as they were regarded as confidential by the organisations that commissioned the work. Evaluations that can be used to predict future behaviours are difficult and costly to conduct. Results are sometimes not available for years, by which time most programs have already changed. This limits the applicability of the results.

• There are gaps and inadequacies in the international data that limit comparisons and analysis (Reuband, 1995). This includes any systematic analysis of the impact of various legislative regimes.

- Few evaluations of treatment services address illicit drug use in any substantive or authoritative manner. Those that exist are equivocal about the effectiveness of various service types or lack of consideration of costs (Pead, 1996).

• Treatment data to describe the patterns of use of services, and the clients of these services, have been inconsistent and unreliable.

- Data gathered by police, the courts and corrections systems are often not comparable, nor is it easy to integrate the data for purposes of evaluation or research. There is virtually no way to track a person's movement through the systems or to assess the impact of the process. Counting methods and definitions constrain comparisons and reliance on longitudinal data.

• Information sharing is not common across services and systems, with data often collected for different purposes and in different formats.

• Researching behaviours that are illegal is difficult. Users are understandably reticent about participating in research and providing reliable answers. Information which includes admissions of illegal activity poses ethical and possible legal impediments to the conduct of useful research since there can be no guarantee of confidentiality.

In this context, advice about reform options should be cautious. Council has heard on several occasions about the risk of 'unintended consequences' of action in this area (Wardlaw, oral submission 1995; Sutton, oral submission, 1996). This is an area where the consequences of action are significant, and where public support and understanding are important. Uncertainty about the consequences of reform and the level of support for any policy option indicates that an incremental and carefully monitored approach is required. Specific action will be required to engage and inform the community, and to better inform policy and program design and operational practice.

Confident policy making and program implementation in this area will require:

• A broadly based research agenda involving collaboration between the Commonwealth, states, academic and service organisations. Research on the impact of various policy initiatives and comparisons across jurisdictions is a potentially significant source of data for monitoring and future planning. It is important that research is initiated and co-coordinated in a national context although there are matters which require research support directly at state level. Commonwealth Government support for drug and alcohol research through two national research centres and an annual grant program has generated important information. Similarly, the State Government has supported some research and has established Turning Point Alcohol and Drug Centre. It has been funded to undertake research and provide clinical services and training. There remain large areas where research could have rapid and direct benefit. Council wants to encourage further research and, to this end, urges ongoing and enhanced support from the National Research Into Drug Abuse program. While integrated funding through bodies such as the National Health and Medical Research Council should also be encouraged, current specific targeted funding remains appropriate.

• Consistent databases across the State Government agencies that have responsibilities in this area. As noted earlier, some data systems within police, courts and correctional services are incompatible. A project to remedy these problems is underway. The Department of Health and Community Services is developing a new database designed to monitor the performance of treatment services. The Coroner maintains a database that is also likely to undergo development as part of a national initiative. Agreement to common definitions, core data and system compatibility is a prerequisite to improving the certainty and confidence of future decision making. Council believes that poor program design and management difficulties often result from inconsistency and gaps in data systems.

• Introduction of local early warning/monitoring systems. Many effective responses to illicit drug use need to operate at the local or street level. A particular need is early warning about changes in the types of drugs and patterns of use in different parts of Victoria. At this stage there are no structures designed to support and coordinate action in local areas, communicate with users, and develop relevant local strategies that minimise harms. A local early warning information system would also provide baseline data that could be linked to broader data systems and then reported back to local areas for comparative purposes. This matter is discussed further in sections on support and treatment and infrastructure.

• Evaluation of the effectiveness of programs. Victoria spends some $100 million annually in law enforcement, education and treatment resulting from illicit drug use. The investigation conducted by Council demonstrates that, in most areas, these funds are applied without the benefit of a strategic framework based on current knowledge about what works in varying situations. The introduction of clear outcome indicators and integrated evaluation processes would provide significant improvements to the current situation. There is a strong reason to believe that targeted evaluations could pay significant dividends in better focused and more effective service provision.

3.3 Demand and Supply Trends

Assessment of the existing and projected scale and patterns of drug supply and demand was an important baseline for Council's deliberations. A wide range of data and perspectives was provided through submissions, consultations and expert hearings.

Key issues raised relating to demand were as follows:

• Our community accepts, and in some cases values, drug use. Alcohol is a central part of many people’s lives. Medicinal drugs are widely used and vital to the health of our community. They are sometimes misused. Illicit drugs are currently used for their psychoactive properties, but potentially some could be used for medicinal purposes (for example, cannabis and heroin).

• Defining some drugs as ‘illegal’ and ‘demonising’ the users has not eliminated their use. Illegal drugs are used by tens of thousands of Victorians. In excess of 30 per cent of our community has used an illicit drug at some time (see chapter 2). These people come from all walks of life and all parts of our State. Some users suffer serious health or other problems as a result of their drug use.

• There is some evidence that problematic and harmful drug use most often occurs where people are vulnerable or lack self-esteem (McAllister et al., 1991). The illegal status of the drugs and the stigma attached to users further entrenches their marginalisation. Provision of information, support and treatment is made more difficult in these circumstances.

• There are potentially serious health consequences that arise from misuse of illicit drugs (table 10). The level and nature of the consequences varies between drugs and is, to some degree, dependent upon the circumstances of their use.

• Use of the major illicit drugs has a direct effect on a very small percentage of the population. However, compared to other countries, the rate of intravenous use of heroin and amphetamines in Australia and Victoria is high and consequently is a problem for users and their associates (see section 2.1.5).

• Data from the National Drug Household Surveys and the Victorian Drug Household Surveys does not indicate that there has been a significant increase in the proportion of people acknowledging use of illicit drugs between 1991 and 1995. The data does, however, suggest that the overall proportion of 18–24 year olds admitting to using illicit drugs has increased slightly from 1993 to 1995. In terms of specific drugs, increases have been recorded for marijuana, amphetamines, hallucinogens and cocaine. Usage rates for other illicit drugs have remained stable or declined.

• The difficulty with extrapolating from this information is that household surveys, due to their nature, are less reliable in obtaining information on highly stigmatised patterns of drug use, such as dependence or intravenous drug use. In particular, they often under-represent high-risk groups such as marginal populations (Pompidou Group, 1994).

• Estimates from the recent review of methadone treatment suggest that there has been a significant increase in number of regular and irregular heroin users in Australia. This review suggests that between 1986 and 1990 there was a 73 per cent increase in the number of regular users, and a 51 per cent increase in the number of irregular users (section 2.1.4). Increasing deaths that appear to be related to using a mix of substances, including alcohol and benzodiazepines, do indicate greater misuse and are a sign of a growing problem.

• Variations in reported prevalence rates make it difficult to estimate the impact increased availability of illicit drugs would have in Victoria. Notwithstanding the difficulties associated with interpreting the available data, a number of comments can be made:

– Males are more likely to use illicit drugs than females, although evidence put to Council suggests that amphetamine use is becoming popular among young women.

– Young males in particular form a large proportion of the drug using population.

– There appear to be lower rates of illicit drug use among employed and married people.

– Prison populations show a high rate of drug use.

Designer drugs, including Ecstasy, appear to be increasingly available. While these are currently at low levels and used among small sub-groups, it is possible that this class of drugs will be increasingly available in the future. It is difficult for Council to predict the future demand for these drugs and it is impossible to predict the harms of barely known substances. It was suggested to Council that increasing interest in quite specific psychoactive effects might contribute to increased demand for this group of drugs.

Key issues raised with Council relating to supply were:

• Global production in illicit drugs appears to be increasing and, despite significant international cooperation, international supply of illicit drugs will continue to grow, possibly at an increasing rate.

• Although not certain, it seems inevitable that some of the increased supply will reach Australia. It is, however, unclear whether increased supply will contribute directly to overall demand. Increased supply can, and almost certainly will, lower the price of some drugs but the consequences of this are hard to predict.

• The Australian Bureau of Criminal Intelligence suggests that increased supply may not have a significant impact in Australia. Heroin is currently widely available throughout Australia at high purity levels and reduced prices, suggesting that sufficient quantities are being supplied to the market.

• Law enforcement agencies throughout Australia have reported that the harder illicit drugs and cannabis were generally readily available throughout 1994.

• Occasional price fluctuations and temporary shortages may indicate either a disruption in the supply or an increase in demand for specific drugs (ABCI, 1995).

• In the case of shortages, when supplies of one drug are limited, there is often a shift to other drugs. There is some evidence to suggest that increased seizures and intensified enforcement efforts can temporarily interrupt established patterns of drug use and sources of supply. This may have the effect of moving users to substitutes or to poly-drug use.

• It is difficult to argue that the quantities of drugs seized are directly proportional to the supply of drugs. Seizure rates are estimated to be low, between 3 to 10 per cent, and seem to exert little influence on heroin price, purity or availability (Weatherburn and Lind, 1995).

During its deliberations the Council was alerted to the problem of inadequate data on illicit drug production.

The United Nations Economic and Social Council comments in its 1995 interim report, Economic and Social Consequences of Drug Abuse and Illicit Trafficking, that:

‘Assessing the economic and social consequences of illicit drug abuse and trafficking implies, first that some measure of the magnitude of the problem is available, and secondly, that there is some conceptual clarity about the nature of the consequences themselves. Estimates of the extent of illicit drug production, distribution and consumption vary enormously, and are often contingent upon the methodology and political orientation of the observer’.

The UN report, while acknowledging that there are no universally accepted figures, supports the view that on the global aggregate, illicit drug production is expanding. This is consistent with advice received by Council from a number of national and international experts (Wardlaw, oral submission, 1995).

The overall relationship between price and escalating demand is not clear. There is a question as to whether the consumption of illicit drugs, like other goods and services, decreases in response to rising prices and increases in response to falling prices. A number of studies suggest that, although small, price elasticities do exist. However, the addition of another variable, such as a successful preventive education campaign, may reduce demand and thereby cause prices to fall, without the falling prices

resulting in more consumption (UN Economic and Social Council, 1995).

On the basis of evidence available to it, Council has concluded that greater emphasis should now be placed on measures to reduce demand for drugs (such as education and health promotion) while maintaining law enforcement as an important control on supply.

Council does not condone drug taking. Nevertheless, it recognises that there will be those who, through ignorance, or other reasons, will misuse drugs whatever the consequences. The major goal of drug policy must be to ensure that people do not take drugs or if they do, that it occurs in ways that minimises the harms caused.

For people who use drugs, information and services aimed at reducing risks should be provided because this may save lives. Information provision should include unambiguous messages that abstinence from drugs is the only totally risk-free option.

Council does not believe that focusing on prevention of use and misuse represents an easy or soft option. Prevention requires multiple approaches and difficult decisions regarding targeting, and the integration of effort across the agencies involved. Minimising unintended consequences requires careful planning and implementation.

Harm reduction as a policy accepts that people use drugs on occasions. The challenge for services which come into contact with drug users is to minimise the harms associated with misuse.

Council’s framework to deal with drug availability, drug use and associated problems includes the following elements:

• Commitment to reducing harm caused by drugs.

• Greater attention to harms and patterns of use of specific drugs.

• Effective control mechanisms that emphasise prevention and variation between drugs and client groups.

• Innovative and up-to-date demand management strategies.

• Emphasis on drug use as a public health problem rather than a crime problem.

• Focus on the drug user as a prime target with intervention designed to reduce emotional, social and physical harm and stigma associated with misuse.

• Collaborative efforts between police, health and other relevant agencies.

• Legislation and law enforcement that is consistent with harm minimisation principles.

• Strong and effective responses to illicit drug trafficking, including heavy penalties.

Council’s approach incorporates a variety of strategies to reduce demand including:

• Information that is accurate, up-to-date and widely disseminated.

• Education that strengthens people’s capacity to make reasonable decisions about drug use.

• Drug treatments that recognise different treatments will work for different people and that most drug dependent people will experience difficulty in stopping use.

• Community action that helps maintain drug users’ links with supportive networks of families and friends.

• Advertising and sponsorship standards that ensure drugs are not seen as fashionable.

• Treatment targeted to high risk adolescents and adult offenders.

• Education, training and work opportunities targeted to young people at significant risk of drug abuse.

3.4 Different Responses To Different Drugs

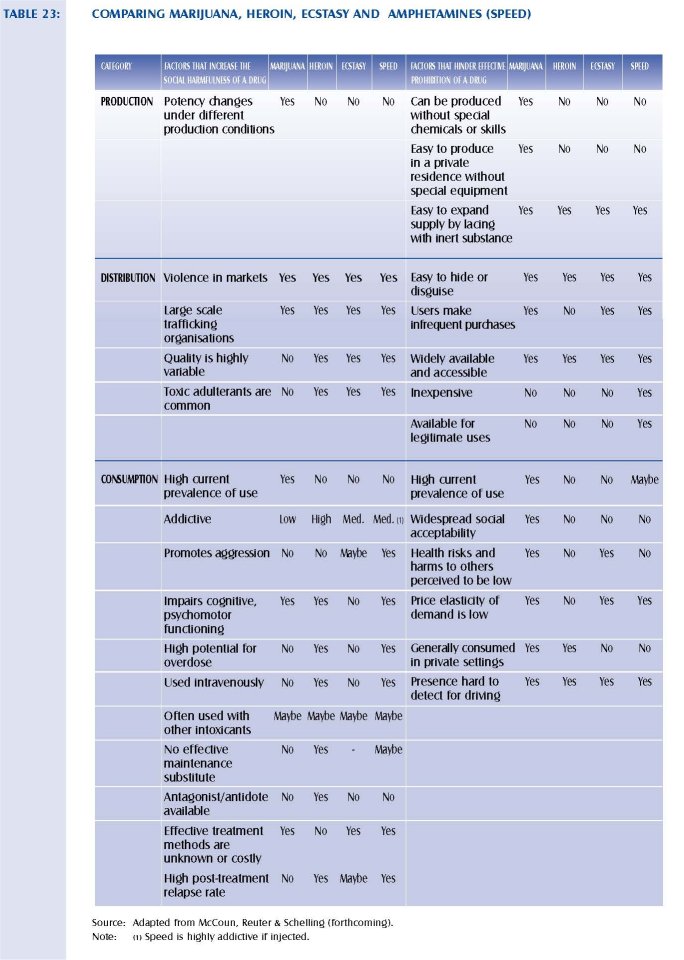

Drugs share many characteristics, in particular risk associated with misuse. However, there are important differences between individual substances. In some cases, these differences appear significant enough to justify varied responses (McCoun et al., in press). Table 23 summarises some of the characteristics that affect response options considered by Council. Analysis and debate revolve around how the production, distribution and consumption of a drug relates to its social harmfulness, and the likelihood of effective control under existing laws.

Use, prevalence and health risks associated with the use and misuse of individual drugs were outlined in chapter 2. Council also considered a range of other information about the most commonly used drugs in Victoria (marijuana, amphetamines and heroin) to assess whether different responses are appropriate for different drugs. Although cocaine is certainly available in Victoria, it was not considered in any detail by Council. Few submissions identified it as an issue and there are almost no problem users presenting at drug treatment services.

3.4.1 HEROIN

In the minds of most Victorians, heroin represents the drug problem at its worst. The prohibition of other, demonstrably less harmful drugs was justified in many submissions on the grounds that their use might lead to heroin. In terms of social cost, heroin dependence under current law is a significant contributing cause of crime, and closely associated with the serious risks of hepatitis B and C and HIV infection.

However, heroin also illustrates the central paradox of drug prohibition: use of criminal law and law enforcement for the protection of public health and morals results in an increase in associated crime and costs to the criminal justice system. Council's discussion with heroin users highlighted the fact that current heroin prices mean most users face the choice of prostitution, theft or trafficking to finance their habit. A constructive linkage between law enforcement goals and treatment is demonstrated by the methadone maintenance program that achieves a measurable reduction in crime and reduced health risks (Goldstein & Smith, 1995).

While many submissions advocated legalisation of heroin, the case for prohibition remains strong. However, Council also acknowledged the costs of prohibition, including increased misery of those who become dependent. To these are added community costs such as the spread of disease, user crime, and the expenditure of scarce law enforcement resources.

A practical response to heroin hinges on maximising the contribution of various programs designed to:

• Discourage initiation into heroin use.

• Control predatory drug trafficking.

• Contain the spread of disease among heroin users.

• Provide easy access to a range of programs that enable dependent users to manage the dependency with a reduced reliance on heroin, or to stop using.

Practical responses also involve the provision of support and treatment to drug dependent people willing to use such services. These are discussed in more detail in other parts of this chapter.

Special attention needs to be given to well-targeted action to prevent initiation. Available evidence suggests general anti-drug messages are of limited value in preventing heroin dependence because those at greatest risk of trying heroin and of becoming dependent are least likely to pay attention to messages from schools or the mass media. Special problems for anti-heroin messages are that only a tiny fraction of any identified population is likely to start using heroin. Thus, if messages have any 'advertising' effect, the number of new users inadvertently attracted could outnumber the number of new or potential users deterred. Consequently, anti-heroin messages need to be targeted very carefully. Current heavy users are likely to be enormously resistant to messages. The prospects of telling them something they do not already know are small and negative messages sometimes contradict their own experiences. To the extent that recently recruited heroin users can be identified by health workers or police, there seems some benefit in making them targets of 'secondary prevention' efforts designed to prevent progression to heavy and dependent use (Kleiman, 1992).

3.4.2 AMPHETAMINES

After cannabis, amphetamines are the most widely used illicit drugs in Victoria. Advice from Victoria's Drug Squad suggests that there is a risk of substantial growth in use of these drugs. Local production continues to provide a readily available supply, despite police success in detecting and closing an average of one amphetamine laboratory a month.

While data remain patchy, there are indications from research studies and official statistics that amphetamine use increased among young Australian adults during the mid 1980s. This was probably because of their widespread availability, their lower cost by comparison with heroin and cocaine, and their relatively benign reputation. Amphetamines appear to be primarily used for recreational purposes in social settings where young people gather to 'party' and have a good time (Hando & Hall, 1995).

Concerns about growth in amphetamine use focus on several issues:

• Australian amphetamine users are more likely to inject the drug than users in other parts of the world. Reasons are unclear, but the apparent increase in the prevalence of injecting amphetamines generates a number of public health concerns. Large individual doses can be fatal. Chronic heavy use can lead to dependence and paranoid psychosis. There is also a high risk that following treatment some users may relapse. In addition, users can become aggressive and violent (Hall & Hando, 1993).

• There are increased risks of motor vehicle and other accidents arising as a result of intoxication from amphetamines and alcohol (Hall, 1993), both of which may lead to aggressive and dangerous driving.

• Many young people do not consider amphetamines to be dangerous. These young people often frequent nightclubs or 'rave' parties and take the drug for the extra energy that allows all night dancing.

• Better organised criminal groups are moving into amphetamine production as a growth market without the inherent risks associated with importation (ABC!, 1995).

• Much production is relatively primitive and there are significant risks of impurities and contaminants in products, adding to health risks for users.

• Withdrawal from amphetamines appears to be more difficult than, for example, heroin.

Practical responses to amphetamines include:

• Legislation to restrict the supply of chemicals necessary for manufacture, law enforcement, and improved national intelligence exchange concerning clandestine laboratories. While significant progress has been made, particularly in developing national legislation relating to precursor chemicals, supply and availability of drugs has not been reduced except for short periods.

• Reducing risks associated with injecting, by improving access to needle exchanges and discouraging unsafe sexual practices among amphetamine injectors.

• Improving information for health professionals about the range of amphetamine related health problems for which young people may seek medical care. In accident and emergency contexts, amphetamines mixed with alcohol contribute to accidental injury and assault.

In psychiatric settings, amphetamine psychoses may be present in young adults with acute psychotic symptoms that remit with minimal treatment over several days (Hall and Hando, 1993). In general practice, concern should be aroused by young adults who come seeking medication to deal with insomnia or who show features resembling a depressive illness.

• A comprehensive training package (From Go to Whoa) has been developed in Victoria for the Commonwealth Department of Human Services and Health and Council urges its promulgation and use.

• Development of effective amphetamine-specific treatment. While replacement programs are now being tested, numbers of dependent users involved are very small. Alternative approaches also need to be explored.

Council's attention was also drawn to a number of initiatives in the Netherlands to minimise harm associated with amphetamine use. These included publication of guidelines for safe organisation and conduct of 'raves' or dances and special facilities to identify, via rapid chemical analysis, the likely content of substances purchased by young people. Both initiatives appear practical approaches to reducing the risks young people face in consuming these drugs.

Ecstasy is a widely used derivative of amphetamines. Ecstasy is probably the best known of a range of so called 'designer drugs'. These drugs can be manufactured to produce a range of different effects on the brain. Council has been advised that the range of such drugs may expand in the next few years. The appearance of such drugs on the market raises new, largely unknown risks to users and uncertainty for health services.

As with amphetamines, usage is likely to occur primarily at 'rave' parties or similar. However, it is possible that as the range of drugs expands, usage patterns may also change. The early warning information service proposed by Council will be vital in monitoring the extent and pattern of use of these drugs.

Although there is evidence of an increase in the use of drugs such as amphetamines and Ecstasy , users of these drugs are only now beginning to appear for treatment. Careful monitoring of new and emerging drugs should be accompanied by development and trialing of appropriate responses which may be similar to existing programs, or new and different interventions.

3.4.3 MARIJUANA

Marijuana is the most widely used illicit drug. Twelve per cent of Victorians have used marijuana in the past year, and this is considerably more than all other illicit drugs combined. Evidence provided to Council regarding a rural police district indicated that more than 90 per cent of police work was drug related. Of this, around 65 per cent related to cannabis, and most of this to use and possession. Use and possession charges also constitute a significant proportion of all charges heard in the Magistrates' Court. Yet marijuana does not loom large among drug problems in terms of observable and measurable harm done to users or to others. It is undoubtedly a powerful intoxicant and can generate a number of serious problems if abused. To decide how large a problem marijuana poses requires judgement of fact and value.

Even if marijuana posed few health risks itself, it would still represent a problem if it tended to lead to the use of other more dangerous substances. Dutch experience indicates that marijuana is not a 'gateway' to heroin. While marijuana is available throughout Dutch cities, there are very low rates of heroin initiation. The most careful study to date, conducted during the 1970s in the United States, explored the marijuana-heroin link among the largely minority-group adolescent population of Manhattan (Clayton & Voss, 1981). Its findings confirmed a relationship between heroin and marijuana, but with an unexpected twist. Heavy marijuana smokers did appear at greater risk of becoming heroin users, but the mechanism did not seem to involve the drug experience itself. Rather, heavy marijuana use appeared to generate involvement in drug selling, either as a way of paying for the marijuana consumed or simply by association with drug sellers. Drug selling, in turn, gave adolescents access to heroin and the money to buy it. This suggests marijuana was a gateway for these adolescents because it was illicit (Kleiman, 1992).

A number of cross-national reviews indicate that response to cannabis would be more effective if it was clearly distinguished from more dangerous drugs. In particular, current levels of marijuana use are more likely to be reduced through education and persuasion than appears likely for other illicit drugs. Marijuana is already widely used and therefore less exotic than other drugs. Therefore there is less risk that discussion in school will create an awareness and curiosity that would otherwise have been absent. By the same token, the target efficiency of the messages—the probability that any given recipient would have seriously considered using the drug now or in the future—is higher for marijuana than any other illicit substance. Benefits of carefully developed education to discourage marijuana misuse seem to outweigh risks (Kleiman, 1992).

During its investigations, Council was made aware that some Victorians may experience significant problems as a consequence of cannabis abuse. Development of a trial treatment service for cannabis users is recommended in chapter 4. Provision of information and support for parents responding to their children's marijuana use was also raised as a significant issue. This is discussed further in the next section. Law enforcement and legislative responses to marijuana are also discussed later in this chapter.

3.5 Information and Health Education

Lack of information and inaccurate information are disturbing features of the Victorian community's knowledge about illicit drugs. While these shortcomings are widely acknowledged, there is less agreement about how information, health promotion and education become active and effective components of Victoria's response to illicit drugs. There has been little planning for a comprehensive, coherent and coordinated information and education approach to illicit drugs in Victoria.

Council believes that prevention must be one of the foundations of Victoria's long-term drug strategy. Dissemination of accurate information, and providing education about drugs within a health promotion framework, is a major component of the Council's proposed strategy.

Health education and information dissemination should always occur within supportive environments. Passive provision of information, even if accurate and well done, will have little or no impact. Information provision in the form of pamphlets, telephone services or curriculum should also take account of relationships between young people's mental status and attitudes to authority—two factors strongly related to drug use.

For legal drugs, primarily alcohol and tobacco, strategies to prevent misuse occur in a health promotion framework. There is now considerable experience in Australia and elsewhere about the effectiveness of health promotion that includes information and education about alcohol and tobacco.

A health promotion approach is likely to make a significant, long-term contribution to reducing use and misuse of illicit drugs. However, the combination and significance of strategies and settings for communicating health messages will be different from those used for legal drugs.

Total population approaches are likely to be more appropriate for drugs that are used by a large segment of the population. The increased prevalence of marijuana use suggests that a health promotion strategy similar to that used with alcohol and tobacco deserves attention.

Focussed strategies regarding the more dangerous drugs are required. Greater attention will need to be paid to ensuring that messages and support services are targeted to user populations and their networks, rather than the general public.

Detailed development of Council's strategy will require considerable community and expert input. An effective framework will require identification of:

• Groups that are the targets of the information.

• Drug(s) to be addressed.

• Behaviours to be targeted (for example, 'safe' use—injecting practices, sharing needles and equipment).

• Means to disseminate the information.

• Desired outcomes (these might include attitudes, knowledge and skills, intended behaviour and actual behaviour with regard to illicit drugs).

3.5.1 COMMUNITY INFORMATION SERVICES

Given that the community receives most of its drug information from mainstream media sources, it is important to facilitate accurate and appropriate reporting as far as possible. The media liaison service that the Australian Drug Foundation offers is an important resource. The media should be encouraged to include information about other targeted services as part of its reporting, such as telephone numbers for further information or advice. The use of community announcements to advertise services might have a role.

The most important specific vehicles for disseminating accurate information to the general community are telephone information and printed materials. However, information provision without other reinforcing activity is unlikely to increase young people's capacity to resist drugs.

Existing specialist alcohol and drug telephone services provide different kinds of information. DIRECT Line provides specific information about the nature and effects of drugs. This information is targeted to those who are contemplating using drugs and their families, and is provided where counselling and referral to specific services is possible. DRUG Info provides a broad base for general information about drugs to the community, and back-up written materials on request. The two services are able to automatically transfer calls where a person's needs can best be met by the other service. Both receive calls from throughout Victoria, but calls from regional and rural Victoria are fewer than expected based on population figures.

Joint promotion of these two services should be encouraged, and opportunities for increased integration explored. Improved data regarding the use of these services is also required for future planning purposes.

Specific strategies are required to address the needs of people from diverse cultural and language groups, and regional and rural communities. Ethnic communities may be better informed through linkages with existing 24-hour interpreter services, recorded messages in languages other than English, recruitment of bilingual staff, and by using ethnic radio and press. Joint promotional efforts would increase the effective use of DIRECT Line and DRUG Info by people from these communities.

The National Drug Strategy has funded development of much printed material over the past ten years. While there have been repeated calls for coordination, printed material continues to be developed in isolation. Pamphlets and other printed materials are most useful when used in conjunction with other broad-based or specific information strategies. Information about illicit drugs, in particular, is likely to be of little or no value on its own.

Council believes that printed materials should be reviewed, and where appropriate for use in conjunction with other information dissemination activities, be translated into languages other than English.

Libraries are an important source of detailed information for the general public. Council has not explored the issue of drug information in general libraries, but notes the value of the comprehensive, specialist alcohol and drug library and information services at the Australian Drug Foundation.

3.5.2 YOUNG PEOPLE, SCHOOLS AND BEYOND

Young people often experiment with drug use, licit and illicit. For a small number, use is chaotic and at problematic levels. Many young people's interest in information is high, particularly where it relates to the functioning of their bodies. Young people are one of the major audiences of mainstream media (particularly television and radio) where they receive information about drugs and lifestyle issues. A range of strategies is required in terms of information provision and education depending upon their developmental stage and social situation and cultural background. Public information is particularly important to assist parents to discuss these issues with their children.

Council believes that efforts to prevent young people using and misusing illicit drugs should be given a high priority.

A hierarchy of approaches exists for responding to young people's drug use. These include broad-based prevention strategies, closely linked to personal and mental health promotion, that aim to prevent the use of drugs when most young people are considering experimentation. This type of program, delivered as an integrated part of the school curriculum, will be all that most young people will need.

Some young people are at a particularly high risk of illicit drug use. It is important to note that these same young people are vulnerable to other health risks, including psychiatric illness, self-damage or mutilation, youth suicide, nutritional disorders, and the broad cluster of problems that are often associated with social disadvantage such as homelessness, family disruption and unemployment. Youth unemployment is strongly correlated with substance misuse (Ray and Ksir, 1990).

To prevent these marginalising circumstances, efforts to support young people are important. Efforts to reintegrate or provide resources and opportunities, such as training programs are likely to be very important drug prevention activities, although detailed consideration of these is beyond the scope of Council.

Council was particularly concerned about the suggestion that there is a lost generation of young people who are using illicit drugs in a destructive way and who, as a consequence, are alienated from mainstream society and are beyond help. This pessimistic view, and variants of it, were put to Council at community and expert forums and in written submissions. Others who spoke to Council had significantly more hope that more could be achieved, first in preventing young people from commencing problematic drug use and second, in intervening to reduce the harms associated with some young people's drug use. This latter view has informed Council's thinking. Council believes very strongly that no young person should be abandoned by the community, no matter how difficult or seemingly intractable many of their problems may be.

Opportunities to provide information exist at youth-specific venues, but it is inappropriate that materials relating specifically to illicit drugs should generally be placed in such venues because of the potential `advertising' effect for non-users. An exception might be where those at high risk of hazardous and harmful drug use congregate, and the use of peer education approaches to reach those especially marginalised. Case management services provide important links for this group.

Response to, and support for, this group of young people are included in later discussions of community involvement, and support and treatment services.

Schools have a critical role to play in informing and educating young people about the role of drugs and their use and misuse in our society. Submissions strongly supported greater priority in this area. Views about when and how this education should be provided were more diverse.

Council heard about efforts of all school systems (government, independent and catholic), individual schools and community bodies to provide school-based drug education. These efforts have primarily concentrated on legal drugs and have produced a number of resources and materials addressing alcohol and tobacco use issues. Much of this effort is positive and deserves support.

However, Council is concerned that some current, widely supported activity does not accord with sound educational principles. Council is aware of the international literature that shows that drug education which is intensive and 'one off' can be ineffective or, in some cases, counterproductive, in fact increasing the likelihood of use. Recent Victorian research confirms these findings (Hawthorne, 1995). Council believes that drug education must be built into the normal structures of education.

Problems arise because the State has had no systematic and formal structure into which drug education fits, and has not equipped schools with the skills and resources to educate students effectively. The absence of a framework has allowed a range of ad hoc initiatives to develop (Hawthorne et al., 1994).

Recent activity has been directed at the development of resources including curriculum guidelines and materials. The principal outcome is the Get Real package developed by the Directorate of School Education (DSE), in consultation with a wide range of relevant organisations. These products are of high quality and deserve support.

Principles to guide school drug education should include:

• Education policy and programs should be consistent across the school environment and developed in conjunction with broader school policy about drugs, and student welfare. School ownership of policy and programs is vital.

• Objectives should be linked to the overall goal of harm minimisation.

• Programs should have sequence, progression and continuity over time throughout schooling and provide consistent and coherent messages.

• Drug education is best included within the health strand of the curriculum, but may also be appropriate to include in other areas such as science.

• Drug education should be delivered by teachers of the subject in which it is included. The teacher should retain responsibility for materials and any other resources used including outside programs.

• Programs should take account of research-based evidence supporting what is effective, and

recognising that what seems like common sense can sometimes be counterproductive.

Success at school levels will also need to ensure that the following issues are addressed:

• Policy development: Schools must develop policies that deal directly and appropriately with the full range of issues about legal and illegal drugs.

• Curriculum space: While Council has not been able to assess the impact on existing curriculum, it believes drug education, incorporating licit and illicit drugs, should be part of core curriculum. While endorsing the need to commence drug education in primary school, Council believes that material relating to illicit drugs should be introduced in the late primary or early secondary curriculum.

• Curriculum content and materials: Further work is required to develop curriculum materials dealing with illicit drugs, particularly cannabis.

• Trained teachers: Council was advised consistently of the importance of ensuring that teachers are pivotal to drug education. Teachers must select and deliver the curriculum and materials appropriate to young people's level, needs and context using the principles outlined above. To deliver this, teachers need to be confident of their competence regarding drug education. This is not currently the case.

Teachers will require enhanced professional development and in-service training opportunities and resources if comprehensive drug education initiatives are to be successful.

Council received some evidence suggesting the presence of illicit drugs in Victorian schools. Given the reported use of drugs by school-age adolescents, this is hardly surprising. Council received no evidence, however, of illicit drug use within school hours.

Schools confront illicit drug use in many ways; drug education within the curriculum, policies relating to drugs and the possible use of drugs at school, and pupil welfare that can involve liaison with parents and community services. The preparedness, capacity, resources and responsiveness to these issues varies widely.

Council heard that some schools had moved to develop strong welfare responses and links to community services, especially those dealing with young people. Other evidence suggested that some schools actively discouraged young people with problems or, at best, provided little support. This leads to an apparent differentiation of schools into what is informally known as 'good' schools (those less likely to retain troubled youth) and 'bad schools' (those schools which worked to retain young people in schools). Further work is required to assess and minimise the long-term damage caused by such differentiation.

Within the school community, there is a small group of young people who are vulnerable to developing serious and lifelong substance use problems. It is important that strenuous efforts be made to retain this group within the school system to enhance their skills, knowledge and preparation for the workplace, and to prevent or delay their labelling and experience of unemployment. Additional resources are needed for this to be effective.

In instances where young people are using drugs, it is important to involve parents where possible, and community-based services in the provision of early intervention or treatment to address drug use issues. This collaboration could be arranged by school pupil welfare coordinators or other appropriate persons.

If the young person leaves school, careful case management into the community and linkage with other facilities and resources could reduce the impact of the sudden lack of support and connectedness to the general community, which makes young people particularly vulnerable to increased and harmful drug use.

3.5.3 TRAINING AND PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT

'While alcohol and other drug problems are relatively common, the majority of human service providers do not receive education and training on how to effectively respond. Consequently, many staff and organisations do not perceive that they have the knowledge, skills, confidence or legitimacy to respond to alcohol and drug related harm. However, a substantial literature has demonstrated that a broad range of human service providers such as general practitioners, nurses and police can have a significant impact on the reduction of alcohol and drug related harm at an individual and societal level.' (Allsop, S., 1996, p.2)

Submissions, expert witnesses and commissioned work brought Council's attention to the role of a wide range of people whose jobs bring them into contact with current and potential drug users. Many of these are professionals in contact with drug users at a time when they may be motivated to change their behaviour.

While specialist services are important to drug users, treatment can be an unnecessary or inappropriate response for some people. Young people and adults are unlikely to seek help or support from specialists until dependency is established and social problems arise. Information, education and practical support can be effectively provided by generalist workers in a range of contexts.

These workers have a potentially critical impact on the provision of information and education about drug use and related issues as part of their principal role. They also have the potential to develop sustainable linkages across the range of health and welfare, law enforcement, and other support services and organisations within the community. This would assist communities to pool their resources and efforts, and provide an integrated response to drug issues.

Incorporating alcohol and drug training in undergraduate courses, and providing ongoing skill development in drug-related issues, has been given relatively little attention, at least partly because of the legal status of many drugs. Making harm minimisation principles relevant to the practice of many professionals can significantly enhance the preparedness and effectiveness of general health and welfare service providers who have an opportunity to intervene with drug users.

An effective strategy to reduce drug use and misuse will, in part, be dependent upon enhancing the knowledge and skills of people like police, doctors, teachers, nurses, welfare staff and youth workers about drugs and a harm minimisation approach. For some of these groups, integrating these matters into existing professional development and training structures is required, and in others, innovative action is needed. Planning in these areas will need to take into account opportunities to make this training part of, or consistent with, accredited educational courses so that participants can gain some professional recognition.

Although there is some shared training between Victorian programs and the National Centre for Education and Training in Addictions in Adelaide, Council believes this is not adequate to address the extent of the need.

There are currently three specific drug-related postgraduate courses available in Victoria. There are also some in other states, including at least one that can be accessed through distance education.

Providing enhanced educational and training opportunities at all levels is important. Council received submissions indicating that there was only a small pool of expert alcohol and drug personnel in Victoria currently and that staff recruitment to specialist programs was difficult. Career opportunities were limited in this relatively small specialist field which indicates that educational opportunities might best be located within broader based undergraduate and postgraduate programs. Council did not examine the current courses with regard to the illicit drug curriculum specifically but believes there are insufficient drug and alcohol educational programs at tertiary levels.

Consistent training for all workers in direct contact with drug users, or people at risk of drug use, would enable better linkages to be made across service systems. Extensive work on development of protocols between specialist drug and alcohol services and other general and specialist services has commenced in some areas, such as child protection and psychiatric services. Some of these are still in their infancy and are currently underutilised. Some remain at draft stage and may lack commitment and resources to implement them.

Council agrees that there is a need to build a core of people from a variety of disciplines who have specialist expertise in substance abuse issues. Building and diversifying the expertise base will also require a long-term investment in higher degrees and research. This is particularly relevant in the professions involved in public health.

Council believes that a strategy for providing education and training is urgently required. This strategy should enable the development of an integrated approach to the provision of drug education across services and organisations.

3.5.4 COMMUNITY INVOLVEMENT

Local government bodies and local communities presented to Council either through submissions, specialist forums or at public hearings. They described initiatives to address specific alcohol and drug issues in their communities. Some of these have been in place for a sustained period, but there has been little attempt at a coordinated local government effort in Victoria.

Advice from groups meeting with Council highlighted the impact of drug use. Advice also highlighted the fact that communities can play a positive role in reducing the harm caused by drugs. Council accepts that there is neither an easy nor consistent way to engage communities whether they be local communities or communities of interest. Fostering positive 'health-oriented' community involvement is likely to be an important ingredient in prevention, education, and reducing the harm caused by drugs.

Communities vary in their level of concern. All share a hope that drugs will not cause problems either directly through use, or indirectly through disruptive behaviour and illegal activity, such as the theft and burglary associated with illicit drug use. Some communities experience heightened concern from time to time that is related to an apparent increase in drug problems or drug-related incidents. The media plays an important part in influencing this level of concern.

The absence of readily available guidelines and well-publicised resources contributes to considerable duplication of effort and frustration. Systematic and reliable information about patterns of drug use and associated harms is usually not readily available at a local level and makes planned responses difficult. This needs to be addressed in an overall effort at enhancing data collection and dissemination.

The involvement and collaboration of major service sectors at the local level are also vital. Council noted examples where this was working well, and others where the different orientation of some sectors contributed to confusion and inconsistent approaches. Intersectoral linkages might occur through a variety of existing structures, such as local government, or sector-specific consultative mechanisms such as Police Community Consultative Committees. Council is not confident that any one of these is necessarily appropriate or working well across all communities.

Current efforts to bring together, document and evaluate these efforts and the subsequent production of guidelines for local action should be supported.

Council noted that the involvement and collaboration of major local service sectors is particularly crucial in establishing strategies and initiatives that address the issues of drug use and misuse among young people. Such strategies and initiatives may include:

• The development of stronger linkages between local services and organisations including schools, youth services, police, sporting and service clubs.

• The establishment of a range of local activities for young people. Young people should be involved in the development of these activities.

• Improving the local public transport service where required to allow young people access and safer travel to entertainment venues within and outside the local area.

• Providing information about drugs and their effects that are appropriately targeted to reach young people where they congregate, or through other appropriate media such as radio and television programs.

Strategies to provide additional support to young people who are particularly 'at risk' and those who have an established drug use problem, may include:

• Providing information about drugs in settings where they congregate, and through appropriate media such as radio and television programs.

• Ensuring access to stable housing.

• Providing assistance in seeking and obtaining employment.

• Re-establishing linkages with their families.

• Providing access to a range of relevant support and treatment services if and as required.

3.5.5 PARENTS

Parents are a critical influence on drug use by young people. This occurs through general care, welfare and provision of guidance and resources, as well as through their own drug use, and their values and opinions on drugs. Parents and peers act as role models and provide information about drugs. A major concern is that misinformation can often take the place of facts.

Parents have stronger influence on younger age groups. While peers become more influential during adolescence, parents remain important and can provide vital stability.

While there were general calls for the provision of information about drugs to parents, there was no clear evidence that parents actively seeking this information had not been able to obtain it.

Many parents of those already using drugs expressed frustration at the lack of information about drug use and related services. Parents with a child who is actively using drugs and sometimes already experiencing severe problems need targeted help. Council heard many distressing stories from parents of drug users. These people were consistently seeking compassion and support and none sought controls or penalties. Many sought assistance for themselves and spoke of the inconsistent advice they received from a range of sources. Some of this advice suggested they 'reject' their child, which they found unacceptable. These parents told stories describing their role in supporting their children that suggested they experienced considerable fear, anger, distress and a sense of impotence. These parents came from all strata of the community.

This group needs specific assistance to deal with their own reactions and to support their child. Where possible counselling should involve interaction between the child, parents and those able to provide support. Council recognises the often complex family relationships associated with drug use and believes that this group might benefit from self-help and other peer support and information initiatives. This was not explored further by Council.

Parents should be encouraged to utilise those whom they ordinarily turn to for support and assistance in their community. This might be a friend, community member, or someone located in a specific service. For those who feel they do not have these resources available, the DIRECT Line telephone service can provide advice, counselling and referral. DRUG Info can assist with information about the drugs that their children are using and printed materials.

Council received advice that in many communities, including ethnic communities, parents often approach religious or community leaders as a first port of call to request information and assistance on drug issues. These parents or religious and community leaders may not be fully aware of resources available. The development of strategies to ameliorate the situation, including those outlined in section 3.5.1, need further consideration. Council's attention has been drawn to the recent seminars organised by the Ethnic liaison Unit of Victoria Police and involving the Centre for Adolescent Health and Odyssey House on 'Drugs in the Greek Community. These seminars aimed to disseminate relevant information to Greek-speaking parents on drugs from the medical, legal treatment, and policing perspective. Further such initiatives should be encouraged and supported.

Improved knowledge and skills relating to drugs and their use could be acquired by parents through increased involvement in schools and promotion of community information services. Information about drugs could also be included in courses or workshops provided for parents (such as parenting skills workshops) by local community organisations. The training of generalist health and welfare workers (including general practitioners, nurses and other health and welfare workers) would increase their ability to provide parents with information and to direct them to appropriate services as required. Schools may also contribute to the knowledge and skills of parents by involving them in issues and activities relating to the provision of drug education within the school.

3.5.6 DRUG USERS

Council was made aware that the provision of prevention and information services to drug users or potential drug users is difficult to achieve, primarily because the illegality of drug use and their mistrust of authorities make them a difficult group to contact. Education targeted to users must therefore be non-judgemental and aimed at harm reduction and safe use. Any insistence on abstinence may impede efforts to disseminate information. Referral to treatment services should be offered on request by the user.

The limited resources or strategies currently addressing the prevention and education needs of drug users concerns Council. Information is currently provided by DIRECT Line, VIVAIDS and at needle syringe exchange outlets.

Drug users are at high risk of suffering the harmful acute and chronic effects of drug use, including HIV/AIDS, hepatitis B and C, as well as the risk of overdose and death. Peer education is likely to be one of the most effective ways of reducing these harms. Drug users who met with Council supported the use of peer-based education. However, Council has also been informed that conventional peer education has not been effective for certain ethnic user groups, and that for these groups outreach services are more effective.

It is clear that hepatitis C is more readily transferred than HIV within the intravenous drug using population. There is a need for further research to determine why this is the case. There is a need to develop targeted education programs aimed at intravenous drug users if the success in controlling HIV spread in the Australian intravenous drug using population is to be replicated for hepatitis C.

3.5.7MEDIA CAMPAIGNS

Council received many written and oral submissions requesting a major media campaign to address the issue of illicit drugs in Victoria. Evaluations of such campaigns conducted nationally and internationally indicate that while they are useful in preparing the community for proposed changes to policy and drug control strategies they have not been successful in convincing users to change their using behaviour. They have also not been successful in stopping use once established. Evidence for their effectiveness in preventing drug use is missing. More dangerously, such campaigns if not very carefully developed, as part of a comprehensive strategy, have the potential to attract some people to illicit drug use.

Major media campaigns are only likely to be used effectively when advertisements are one component of a broader strategy. Evaluation of Victoria's successful campaign to reduce alcohol-related road fatalities has clearly demonstrated the importance of police activity (including speed cameras, booze buses, targeted sponsorships and education) in delivering the impact of key messages in television advertisements.

Council believes that media campaigns should only be used to communicate major changes to policy and arrangements in Victoria: where appropriate, this should be in cooperation with the Commonwealth Government.

Illicit drugs differ from other issues commonly dealt with in media campaigns because they effect a small percentage of the community. Messages targeted at this group run the risk of communicating unintended messages to non-users. They would also have a poor cost benefit return.

Council urges ongoing liaison between journalists and those in the drug and alcohol sector, particularly those involved in information provision. While various efforts could be made to develop appropriate codes of conduct, Council recognises the difficulty of consistently implementing these. This is an area that may warrant future attention.

3.6 Support and Treatment Services

A wide range of problems and issues confront many people who use drugs. The services available to assist them range from the informal through to highly specialised drug and medical services. During its deliberations, Council received wide-ranging input about support and treatment for drug misuse. At times, the same information was used to draw widely divergent conclusions about support services for drug users. The same services were highly praised by some submissions and heavily criticised by others.

Council has not endeavoured to be comprehensive but has examined identified problems and searched for achievable solutions. Council believes that the problems of youth deserve special attention and it has accordingly considered these issues in a separate part of this section. Similarly, the issues for drug users who come into contact with the criminal justice system warrant increased attention and a specific discussion of these issues is included.

Council is aware that there are other vulnerable groups who use illicit drugs; for example, opiate-dependent women with young babies. Many of the issues surrounding this group relate to the absence of adequate family support and general welfare services. Shortages of these services work against these often fragile families gaining the necessary skills to meet the developmental and survival needs of vulnerable young babies and children. This, in turn, may lead either to tragedy, or the precipitous and repeated engagement of child protection services. Solutions to these problems do not lie in the expansion of specific drug and alcohol services but rather a stronger and more able generalist health and welfare sector capable of responding without prejudice to the medical, dental and other care and support needs of opiate or other drug dependent women and their families.

Homeless people are another vulnerable group who experience difficulties in accessing services in the general health and welfare system. Such people are often living on the fringes of society and this increases their chances of having a range of problems, including illicit drug misuse.

Chronic pain sufferers constitute a special group of opiate-dependent people. Issues surrounding this group are, however, not discussed in detail.

Council believes that proposals developed in respect of treatment and support services, although not directly addressing the needs of these groups in detail, will benefit them.

The community and professionals working in all support, treatment and related sectors need to be aware of the importance of illness prevention approaches with illicit drug users. These may include provision of information and education as well as counselling and, for some, substitute drug therapies.

Information and advice about the prevention of spread of blood-borne infections, improvements in nutrition, and sexual health are especially important. Council notes that the needs of injecting drug users require special attention. It may be appropriate that injecting drug users be encouraged to use in less harmful ways, such as inhaling, smoking or snorting.

The provision of secondary consultation by the Drug and Alcohol Clinical Advisory Service is an important means by which the capabilities of generalist health and welfare professional are strengthened to deal effectively with clients who have substance use problems.

It should also be noted that people who take illicit drugs usually take more than one drug simultaneously, although they might have a drug of preference. This phenomenon is described as poly-drug abuse and commonly increases the harms associated with drug use.

3.6.1 SUPPORT SERVICES

PEER SUPPORT AND SELF-HELP GROUPS

Many drug users have had negative experiences that have resulted in an enduring sense that they are alienated from the community and not able to access services. In this context, they have found the support and advocacy offered by peer support groups invaluable. Council has also formed the view that these organisations are vital. Their potential as a link into other services and legal systems is currently underdeveloped. For example, organisations offering peer-based support are successful in delivering family and other support services that have credibility and relevance to users, but also take account of the needs of user's children (McGregor, 1994).

Council urges that these services should be consulted extensively about their role with a view to developing more sophisticated use of the expertise.

NEEDLE SYRINGE EXCHANGE PROGRAMS (NSEP)

Needle exchange programs (NSEP) playa critical role in reducing rates of infection and safer injecting practices, be they provided by outreach services or at fixed locations usually in health centres. Council also acknowledges the important role NSEPs play in providing education to users and, where requested, referral to treatment agencies. Many pharmacies also provide needles, syringes and, where appropriate, advice to users.

Growth in the number of needles/syringes distributed in recent years is evidence both of the demand and support for these programs. Council heard several descriptions of positive and collaborative efforts to maintain individual services. One example involved police and local health services in St Kilda.

The NSEP program remains contentious for some people and examples of local community reluctance to accept these services was apparent. There are important planning decisions that need to be considered, including the harms that result to users and others from unsafe injecting practices. Long delays in establishing NSEPs have hidden and potentially significant costs for the community that must be actively balanced with local issues.

Council was advised that injecting drug use continues in Victoria's prisons despite vigorous attempts to eliminate drugs. In the absence of provision of clean injecting equipment, intravenous drug use in this environment is likely to be high risk. Council accepts that management of this situation requires careful consideration.

3.6.2 ACUTE SERVICES

Individuals experiencing problems with illicit drug use may develop problems that require emergency care. Currently, help may be sought in the emergency rooms, the psychiatric care system, from general medical practitioners and the ambulance service. These services are an important link in the acute care system that supports and treats people with drug problems.

Council was advised that the ambulance service plays a vital role in responding to drug use, particularly in the case of overdose or suspected overdose. Ambulance officers are able to provide general health care and, in the case of a heroin overdose, administer a drug (Narcan) which rapidly counteracts the effect of heroin.

Council was advised that some young drug users believe that the ambulance service will notify either their parents or the police if called. As a result the ambulance service is not called to some overdose situations, dramatically increasing the risk of death. Council believes this issue should be addressed through policy and practice guidelines and protocols.

3.6.3 SPECIALIST DRUG TREATMENT SERVICES

SERVICE REDEVELOPMENT

Victoria has been a leader in the development of many drug and alcohol services over the past thirty years. Council noted, for example, the respect that a number of experts from elsewhere in Australia and from overseas have for the Victorian Methadone Program. This program is delivered largely through general practitioners and community pharmacies rather than specialist clinics.