2 ILLICIT DRUGS: CONTEXT AND FACTS

| Reports - Drugs and our Community |

Drug Abuse

2 ILLICIT DRUGS: CONTEXT AND FACTS

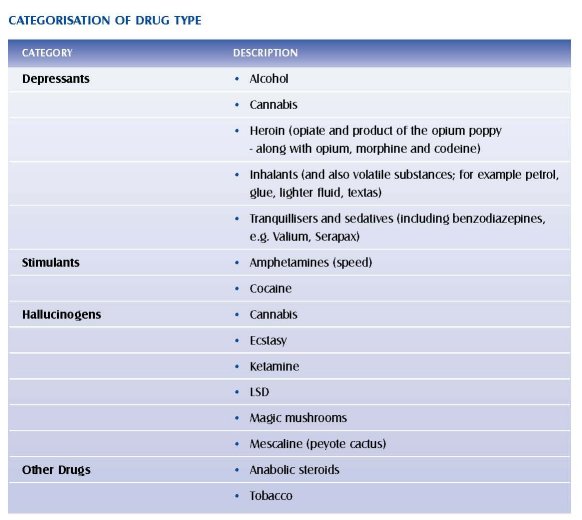

The Council's terms of reference require it to consider issues and options relating to illicit drugs. Figure 1 categorises and briefly describes a range of drugs, both licit and illicit. It is important to recognise that the illicit drugs are, in functional terms, the same as legal drugs. Alcohol and tobacco have a considerably greater health impact because of their widespread use.

Throughout the consultation process, the Council received comment about the use and dangers of inhalants, misuse of legal drugs (principally pharmaceuticals), and anabolic steroids. While recognising the importance of these problems and the overlapping issues regarding the causes of drug use, educational opportunities and treatment strategies, the Council has focused on five major drugs:

• Heroin

• Cannabis

• Amphetamines

• Cocaine

• Ecstasy and designer drugs

Council is also aware that misuse of inhalants is a problem with very young adolescents and can have seriously detrimental effects on their health. The misuse of legal substances legally available has not been a major focus of this inquiry.

The Premieres Drug Advisory Council is not the first such body to address these issues in Australia.

During the 1970s and 1980s in particular, there was a series of commissions and inquiries into drugs; the most relevant are listed in appendix 5. A number of common themes were addressed by these bodies, including investigation of the importation and distribution of illicit drugs, the consequences of illicit drug usage, law enforcement, and treatment options. In addition, most also examined the dimensions and consequences of licit drug use, in particular tobacco and alcohol.

2.1 Nature and Extent of Trafficking and Use

SOURCES OF ILLICIT DRUGS

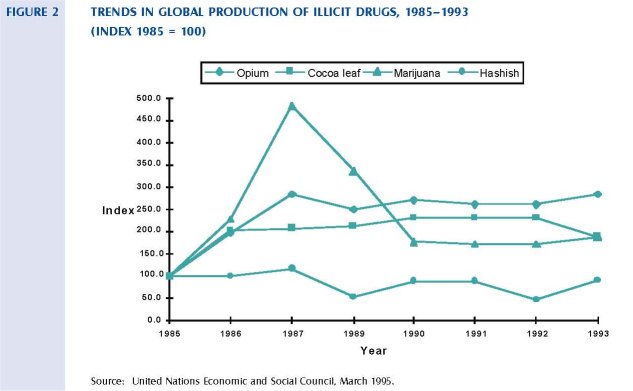

In 1995, the United Nations (UN) Economic and Social Council's Interim Report: Economic and Social Consequences of Drug Abuse and Illicit Trafficking, commented that although there are no universally accepted figures on illicit drug production, trends indicate that worldwide production is expanding. The trends in global production from 1985 to 1993 are presented in figure 2. These data suggest that global coca and cannabis production, after rising dramatically in the 1980s, has levelled and decreased in the 1990s. In contrast, global production of opium (from which heroin is derived) is still rising.

The overwhelming majority of illicit drugs consumed today are plant products, or plant products that have undergone some semi-synthetic processes. Illicit crop cultivation is concentrated in certain geographic areas, but it frequently shifts within, and sometimes between, continental subregions. Synthetic drug markets are, however, developing rapidly. The Australian Bureau of Criminal Intelligence (ABC!) details the major sources of illicit drugs in Australia in the 1994 Australian Illicit Drug Report. The information is summarised in the following section. The 1995 report will be available in the later part of 1996.

CANNABIS

Most of the world's cannabis is produced in Lebanon, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Morocco, which together in 1993 produced an estimated 1150 tonnes of cannabis resin (hashish). However, the vast bulk of cannabis consumed in Australia is grown locally in open-air plantations, or in indoor hydroponic nurseries. Supplies of concentrated cannabis products (hashish and oil) come mainly from South-East Asia. The most common importation method is by mail and larger quantities arrive as sea or air shipments. Smaller quantities are carried by individual couriers.

HEROIN

The four main areas of opium production affecting Australia include:

• The 'Golden Triangle' (Burma, Laos and Thailand).

• The 'Golden Crescent' (Pakistan, Afghanistan and Iran).

• The Middle East (including Lebanon).

• The Andean Region (Colombia, Peru and Bolivia). Although Mexico and Colombia also produce opium, the ABCI reported in 1995 that there were no indications that this heroin has reached Australian markets (ABCI, 1995).

Worldwide production of heroin in 1993 was estimated to be 3699 tonnes. The Golden Triangle was the largest single producer at 2797 tonnes (UN Economic and Social Council, 1995). About 80 per cent of heroin seized in Australia can be traced to the Golden Triangle. There is evidence that suggests that much heroin now comes to Australia from Burma through China to Hong Kong, rather than via Thailand. In addition, Vietnam is also emerging as a transit country for heroin. Heroin is imported by a number of methods that include individual couriers, concealed in cargo and on ships disguised as fishing vessels, and on light aircraft using the northern Australian coastline.

AMPHETAMINES

Amphetamines are generally locally produced in clandestine laboratories and only very small amounts are imported into Australia. Law enforcement strategies have targeted illegal laboratories that are sometimes found in rural areas. Twenty-nine clandestine laboratories were detected making amphetamines in Australia during 1994. In Victoria, nine laboratories were located in rural locations and two in suburban Melbourne (ABCI, 1995).

Amphetamine production requires the supply of essential chemical precursors that are available legally in Europe and the USA. Most jurisdictions in Australia have introduced legislation to control access to these chemicals. Interstate distribution is by truck, car or motorcycle, as well as by domestic air travel. Jurisdictions also report use of courier and postal services to distribute amphetamines. Evidence put to the Council suggests that some motorcycle gangs are involved in the manufacture and distribution of amphetamines throughout Australia, although it is clear that production and distribution also occurs through other channels.

OTHER DRUGS

The world's supplies of cocaine are nearly all produced in South America. Level of importation of cocaine into Australia remains low compared with other illicit drugs. Cocaine reaches Australia mainly by being imported via the USA and/or Europe. This adds to the cost of the drug. LSD is produced in clandestine laboratories in the USA, United Kingdom and the Netherlands and there is no evidence of manufacture in Australia. It is easily imported because of its small form, usually tablet. There were a number of new developments in the illicit drug trade in Australia during 1994 with emerging drugs including Nexus, PMA, Cloud 9-Yohimbix 8, Ketamine, GBH. It has been suggested that the range of designer drugs is likely to increase.

2.1.2 PRICE AND PURITY

Due to its illegal nature, the quality, composition and purity of street drugs is unknown and can be highly variable. There is no mechanism for ongoing monitoring of prices and purity levels. Heroin purity is generally measured as the percentage of heroin in a given sample. In its pure form, heroin is relatively non-toxic to the body and causes little damage to body tissue and other organs. It is however highly addictive and, depending on dose, can arrest breathing. Street heroin is usually a mixture of pure heroin and other substances known as cutting agents such as talcum powder, baking powder, starch, glucose or quinine. These additives can be highly toxic and can cause chronic health problems. Their presence also contributes to accidental overdose and death as a result of users being unaware of the level of purity of the heroin they are using. Information provided to the Council indicates that heroin is currently readily available in Victoria at relatively low prices. Drugs seized by the Victoria Police are analysed to determine their purity, packaging and additives. This information is often used as evidence in contested court cases and is not generally available to the public.

Purity levels are also variable in other types of illicit drugs. For example, the level of delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the primary psychoactive constituent in cannabis, can result in differing effects on the user. Hashish has a high level of psychoactive potency and more concentrated levels can have more extreme effects. Cannabis products available in an unregulated market will invariably have a range of THC levels. As a result, the majority of users will not be aware of the potency of the product and will therefore be at some degree of risk.

Amphetamines are also available in differing levels of purity and can be mixed or 'cut' with other substances. The quality of amphetamines varies slightly from state to state and, particularly at the street level, the level of purity is generally low. This suggests greater demand and the practice of adulterating the amphetamine to meet this demand (ABC!, 1995). The effect of controls on the

necessary chemical precursors may also influence the level of purity, and results from a need to further 'cute the product to maintain a constant supply. Very little is known about the level of purity of cocaine in Australia. As with heroin and amphetamines, cocaine is also available in varying levels of purity.

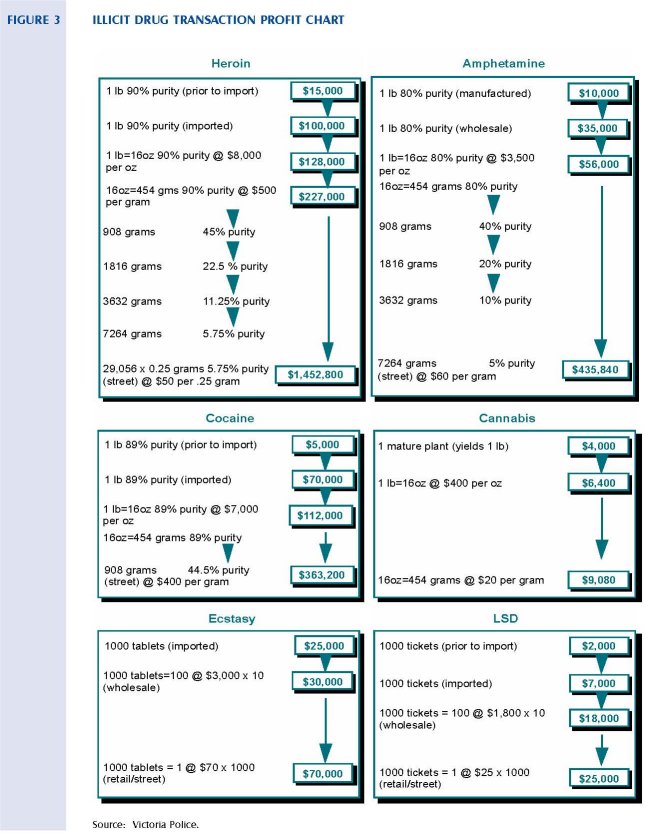

It has been estimated that more than 90 per cent of the value added (gross profit) of cocaine and heroin is generated at the distribution stage of the illicit drug industry (UN Economic and Social Council, 1995). Figure 3 charts the transaction profit of the major illicit drug types under review. It shows the value added to a given quantity of specific illicit drugs at each stage of the distribution process. Prior to importation, one pound of 90 per cent pure heroin is worth approximately $15,000. The value added to this quantity of heroin accumulates during the importation and distribution phases and, depending on the final level of purity, this original amount of heroin could be worth as much as $1.4 million (based on 5.75 per cent purity and sold at $50 per 1/4 gram). Heroin, cocaine and amphetamines generate the highest profits. This is largely due to the ability to mix or 'cut' with other substances, thereby reducing their level of purity.

2.1.3 THE COST OF ILLICIT DRUG USE

Economic and social costs of drug use are considerable. In Australia, the costs of licit and illicit drug misuse were estimated to be equivalent to 4.6 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP) in 1992. Of this, illicit drug misuse was estimated to account for 0.5 per cent of GDP (UN Economic and Social Council, 1995). The largest part of this involves drug-related crime and law enforcement. A similar investigation conducted in the United Kingdom and commissioned by the European Community found that identifiable costs of drug trafficking and abuse amounted to 1.8 billion pounds sterling in the United Kingdom in 1988, and also accounted for some 0.5 per cent of GDP (UN Economic and Social Council, 1995).

The health costs of a drug-dependent person are estimated to be some 80 per cent higher than those of the average citizen in the same age group. Special concerns arise because drug use occurs most frequently in the 15-35 age group that includes young people entering or about to enter the workforce. Given current unemployment rates, entry into the workforce is a major problem. Abuse of illicit drugs reduces chances to enter or remain in the workforce, while frustration from failure to find employment favours drug consumption and creates a vicious circle (UN Economic and Social Council, 1995).

Social costs of drug misuse are less easily quantified; however, their impacts may be more insidious. Social integration and cohesion (at the family, community and even broader levels), are almost always compromised by an escalating drug problem. The lifestyle associated with that misuse can contribute significantly to destructive anti-social behaviour, violence and child abuse, loss of employment, financial hardship, dependency, and social marginalisation.

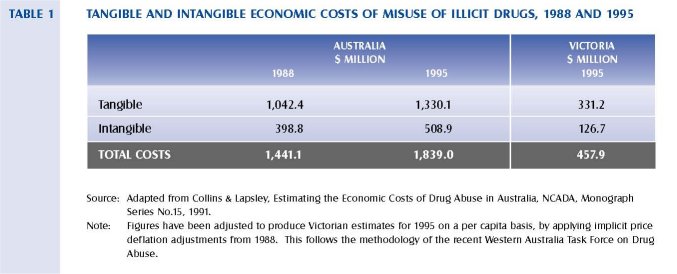

Data gaps and limitations make precise estimates of the cost of illicit drugs impossible. However, the authors of the most comprehensive and methodologically sophisticated Australian study to date indicate that a conservative estimate for Australia was in the area of $1.44 billion in 1988 (Collins and Lapsley, 1991).

Collins and Lapsley include both tangible and intangible costs in their model that has been applied to alcohol and tobacco as well as illicit drugs. Major differences emerged between licit (alcohol and tobacco), and illicit drugs regarding the estimated proportion of tangible rather than intangible costs. Nearly three-quarters of total economic costs of illicit drugs were tangible compared to 12 per cent for tobacco and 53 per cent for alcohol. Major contributions to the economic costs of illicit drugs were the resources that would be available for other purposes if consumption of illicit drugs ceased, which accounted for about half of the total costs. Law enforcement costs accounted for a further 25 per cent of total costs and net production costs another 24 per cent. `Net production costs' attempts to estimate the resources rendered unavailable for community consumption or investment as a result of loss of production due to mortality and morbidity.

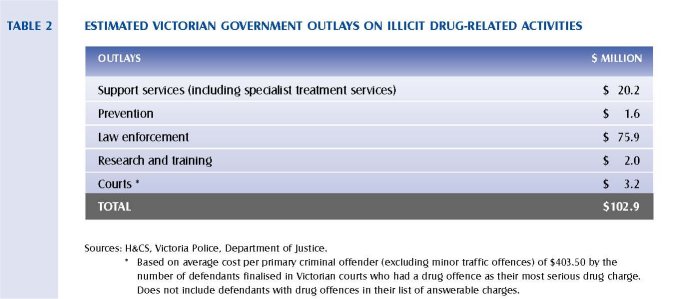

Estimated total economic costs of illicit drug misuse as estimated by Collins and Lapsley for Australia in 1988 are set out in table 1. This model does not account for the costs of all use; rather it focuses on misuse of drugs. Using these figures as a base, a conservative estimate of the cost of abuse of illicit drugs in Victoria in 1995 is about $458 million.

The current estimated State Government outlays on illicit drug-related activities are presented in table 2. It is clear that the majority of expenditure in this area is spent in the area of law enforcement: approximately 74 per cent of the total outlays. It must also be noted that these figures do not include the expenditure of federal agencies (such as the Australian Federal Police, the National Crime Authority and the Australian Customs Service), that can be attributed to activities in Victoria. It should be noted that these figures are based on those police officers exclusively employed in drug law enforcement and therefore underestimate the numbers of police involved in drug-related work. Similarly, calculating court costs on those cases directly related to drug offences underestimates the number of crimes that are drug-use related (Marks, 1992). In addition, the capital and recurrent costs of housing prisoners charged with drug offences are substantial, although difficult to quantify, and are not included in this table. As a result, caution should be taken in assessing these figures.

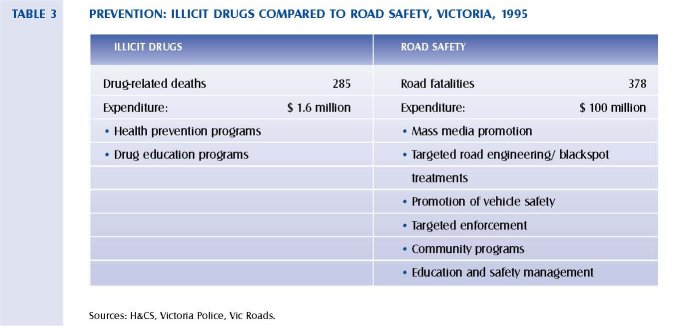

In Victoria, an estimated 285 people died from illicit drug-related deaths in 1995. In comparison, there were 378 fatalities on Victorian roads. It is interesting to note the significant difference in funding that is allocated for prevention programs addressing these issues. The high level of investment in road safety programs (approximately $100 million per annum), has resulted in a marked decrease in road fatalities of about 45 per cent in five years.

The Council notes that a large proportion of the costs attributed to road accidents actually relate to injury rather than fatalities, and that these injuries almost certainly will exceed those related to drug misuse.

2.1.4 PREVALENCE RATES AND PATTERNS OF USE

The level of illicit drug use in Victoria, relative to licit drug use, is not high. However, indications are that the worldwide supply of some drugs, especially heroin, will impact on the levels and patterns of drug usage in Australia. Evidence presented to the Council indicated that high-purity heroin is more freely available, at lower prices, in Victoria than in the past. This raises a number of questions

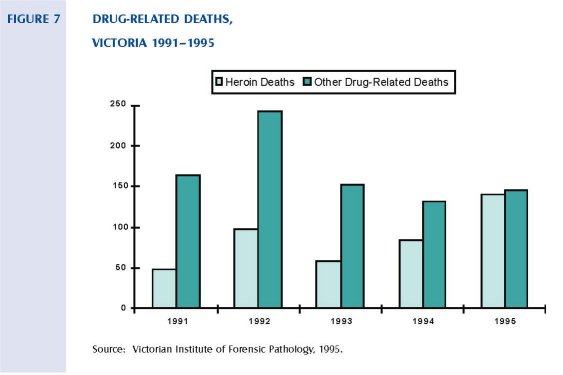

concerning increased initiation among young new users. In addition, the number of heroin-related deaths in Victoria increased significantly during 1995, and now accounts for half of all drug-related deaths reported to the State Coroner. This is addressed later in this chapter (see figure 7).

Population-based approaches, such as household surveys, aim to measure behaviour, knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and the relationships of lifestyle and other factors to drug use in a representative sample of the general population. It is argued that while they are the only way of obtaining relatively direct measures across the population as a whole, they are less valid with respect to the highly stigmatised nature of drug use. They also undersample or miss high-risk groups such as marginal populations, homeless people, or prisoners (Pompidou Group, 1994).

In Australia, the major sources of data on illicit drug usage are the Victorian Drug Household Survey and National Drug Household Survey. It should be noted that these are a general tool for gathering material on all drugs, not just those regarded as illicit. The Council has accepted advice that the nature of the surveys and their size is likely to lead to some understating of the prevalence of use in the community. They are, however, the only substantial and ongoing data-gathering tool available.

DUE TO THE NATURE OF HOUSEHOLD SURVEYS, HEROIN USERS ARE LIKELY TO BE UNDERREPRESENTED. LEVELS OF REPORTED USE SHOULD BE SEEN IN THE CONTEXT OF A NUMBER OF FACTORS ADDRESSED LATER IN THIS REPORT INCLUDING:

• A significant increase in the number of heroin-related deaths since 1991, which accounts for half of all drug-related deaths in 1995.

• Eleven per cent of all calls to DIRECT Line over a two year period concerned heroin.

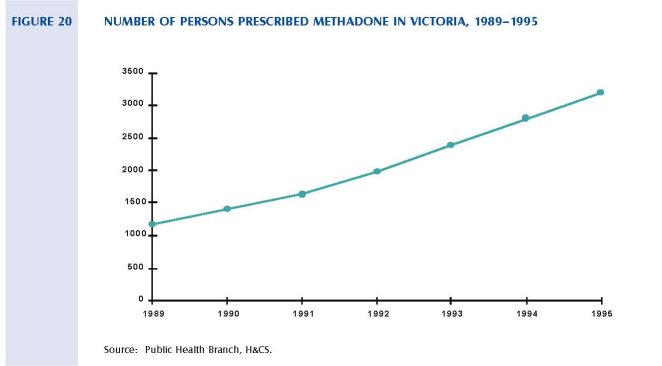

• A substantial increase in the number of people being prescribed methadone from 1989.

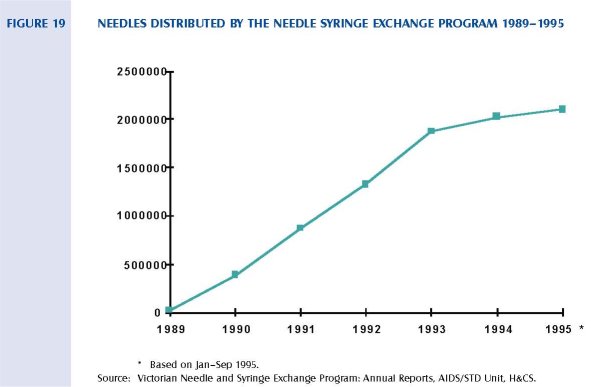

• An increase in the number of needles distributed by the Needle Syringe Exchange Program (NSEP), with over two million needles and syringes being distributed in 1995.

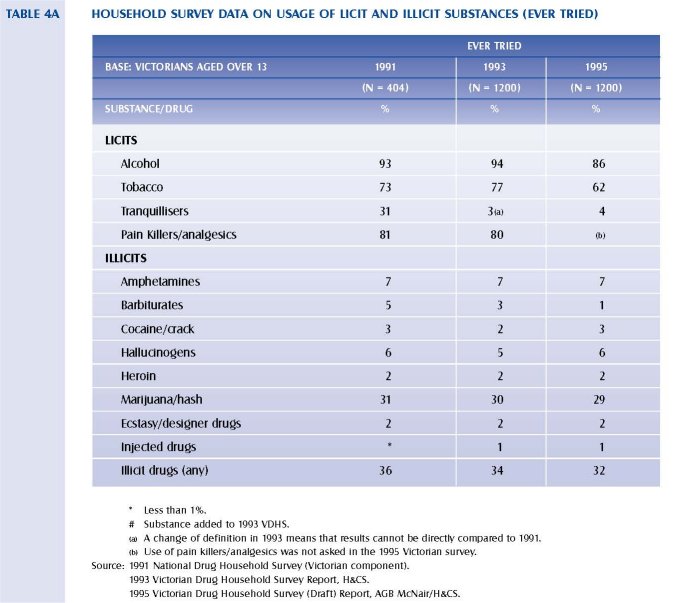

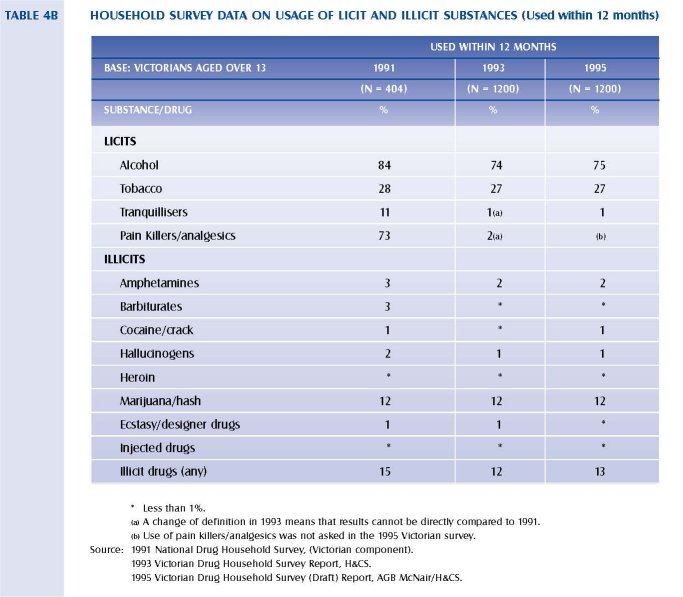

Table 4a and 4b show the level of substance use in Victoria in 1991, 1993 and 1995 as reported in the drug household surveys. These figures should be treated cautiously due to the small numbers reporting illicit drug use.

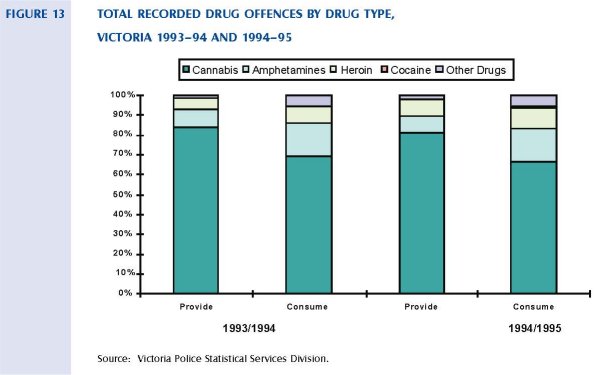

Although it would appear that the prevalence of heroin and cocaine use is similar, it is clear that heroin is regarded as a more severe social problem. There is some anecdotal evidence to suggest that cocaine users are more likely than heroin users to be sampled in such studies. Later in this section information is provided on drug offences by drug type (figure 13). These figures show that cocaine offences account for 0.1 per cent of all drug offences compared to heroin, which accounts for about 10 per cent.

The apparent overall prevalence of illicit substance use, according to the survey data, has slightly declined over these years with 32 per cent of Victorian adults having used at least one illicit drug in their lifetime in 1995 compared to 36 per cent in 1991.

Marijuana is by far the most common illicit drug ever used with 29 per cent in 1995 having used marijuana/hash, 7 per cent having used amphetamines, and 6 per cent hallucinogens. Only 2 per cent of the population surveyed indicated that they had used heroin at least once in their lifetime, and less than 1 per cent had used it within the past 12 months.

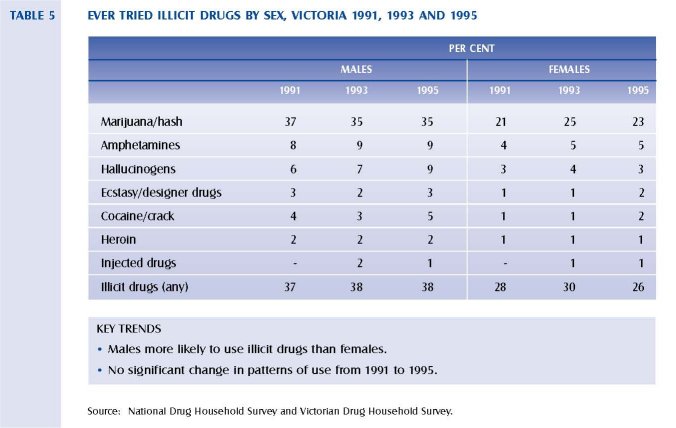

The use of illicit drugs is higher among males than females, with 38 per cent of those males surveyed having used an illicit drug at least once compared to 26 per cent of females in 1995. Illicit drug use is more prevalent among males than females for all types of drugs. In 1995, 35 per cent of males had used marijuana at least once in their lifetime, compared to 23 per cent of females.

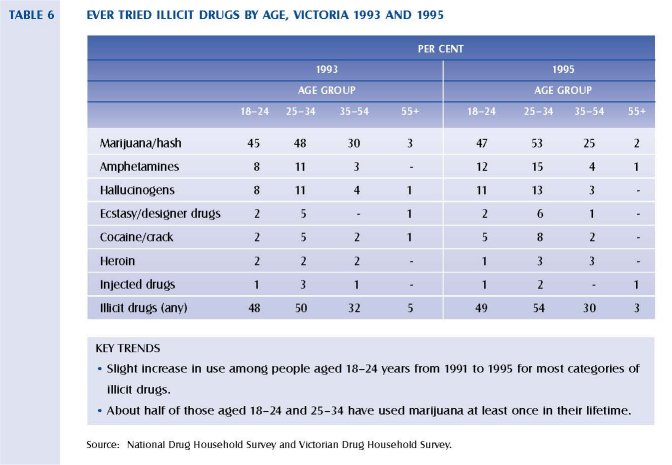

Illicit drug use was markedly higher for people aged less than 35 years of age than for older age groups.

In 1995, 54 per cent of people aged between 25 and 34 had ever used an illicit drug, compared to 30 per cent of people aged between 35 and 54 years of age, and only 3 per cent of people aged over 55 years of age. The proportion of people aged between 25 and 34 who had tried marijuana increased from 48 per cent in 1991 to 53 per cent in 1995. There was also a increase in the proportion of this age group who had ever used amphetamines, rising from 11 per cent in 1991 to 15 per cent in 1995.

Younger people, those aged between 18 and 24, were less likely to have ever tried heroin than those in this age group surveyed in 1993. There was, however, an increase in the proportion who have ever used marijuana, amphetamines and hallucinogens. These figures should be treated cautiously because, due to their nature, household surveys are unlikely to pick up young heroin users whose parents do not know they are users, or young people not living in households.

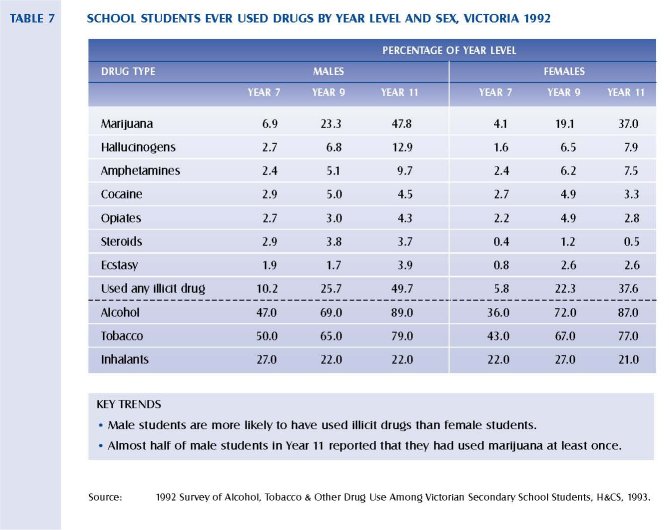

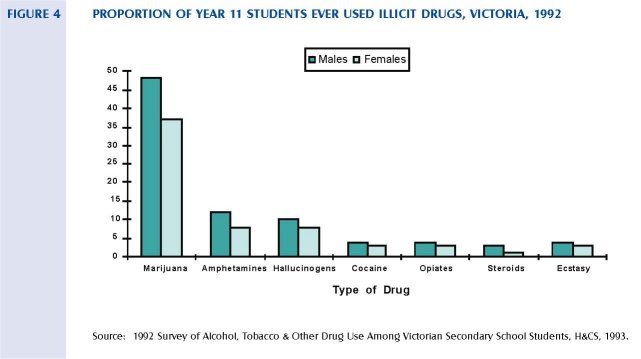

The proportion of students who have used an illicit drug increases with each year level from 10.2 per cent (males) and 5.8 per cent (females) at Year 7, to 49.7 per cent (males) and 37.6 per cent (females) at Year 11. The proportions of students in Year 11 who have ever used illicit drugs are similar to those in the adult 18-24 age group.

Use of inhalants, while not illicit, is high among school children, with over 20 per cent of boys and girls in Years 7, 9 and 11 having ever used inhalants. Illicit drug use among school students indicates similar trends to that in the adult population, with a higher prevalence of use among males compared to females. The most common illicit drug ever used was marijuana, having been used by 49 per cent of males and 37 per cent of females in Year 11. Hallucinogens and amphetamines were the next most common illicit drugs used by Year 9 and 11 students.

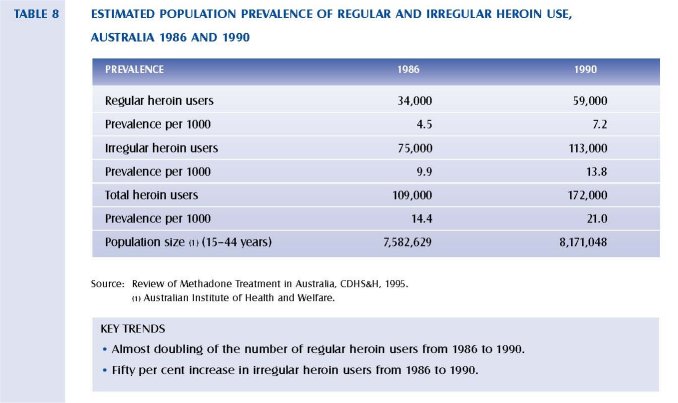

The Commonwealth Department of Human Services and Health has recently released a report titled Review of Methadone Treatment in Australia, which attempts to estimate the population prevalence of opiate dependence in Australia. Methodological difficulties notwithstanding, the report compared the estimated population prevalence of regular and irregular heroin use occurring in 1986 and 1990 and found statistically significant increases in both types of usage. The results of these calculations are presented in table 8.

These calculations suggest that the estimated prevalence of regular heroin users (per 1000 of population) had increased from 4.5 in 1986 to 7.2 in 1990. The estimated prevalence of irregular heroin users had increased from 9.9 to 13.8 per 1000 population, while the estimated prevalence of all heroin users increased from 14.4 to 21.0 per 1000 population. The report states that these increases are statistically significant (CDHS&H, 1995). Current indications are that the number of heroin users has continued to grow since 1990.

2.1.5 INTERNATIONAL COMPARISONS

Examining international, Australian and Victorian trends in the patterns of illicit drug usage is central to assessing the effects changes may have at the local level. However, as outlined in the study undertaken by the Pompidou Group (1994), it is not easy to obtain valid information on phenomena that are often illegal, stigmatised and hidden. This continuing study began in 1983 and aims to improve the quality, usefulness and comparability of indicators of drug misuse, as well as monitoring and interpreting trends in drug misuse across a network of major European cities. The Pompidou Group stresses the difficulty in comparing countries or cities where there are important differences in definitions, traditions, legal and institutional arrangements, and perspectives on drug misuse, policies and interventions. The task of interpreting the data is therefore of central importance.

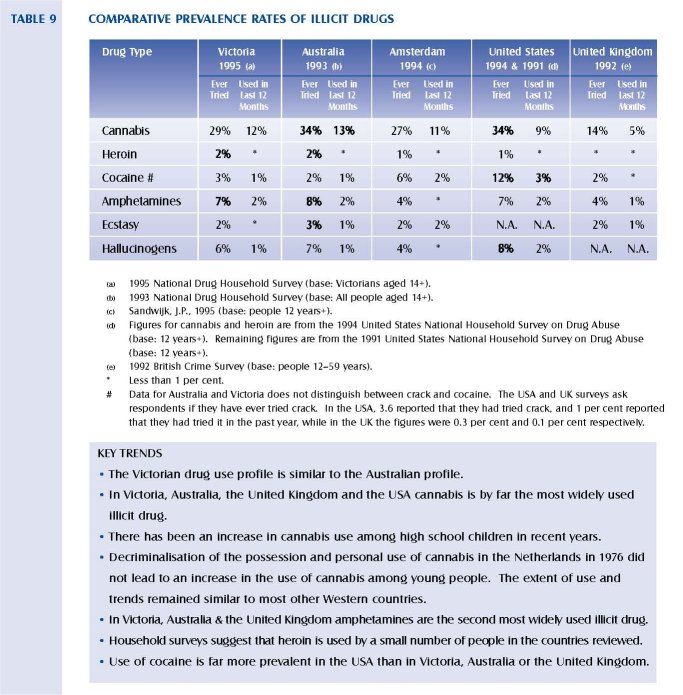

While acknowledging these difficulties, information on patterns and the extent of drug use provides the basis for which effective and strategic drug policy can be developed. Prevalence data from three overseas countries is compared to data from Victoria and Australia in table 9. The qualifications as detailed earlier in comparing prevalence rates between countries should be kept in mind when examining this information. The most recent data available to the Council is presented here.

Cannabis is by far the most widely used drug in all cases, although reported rates of prevalence in the United Kingdom are significantly lower than in other countries. Only 14 per cent of those surveyed in the United Kingdom in 1992 had ever used cannabis. Amphetamines are the second most used illegal drug in Victoria, Australia and the United Kingdom, and cocaine is the second most used drug in the USA and Amsterdam. As noted earlier, the apparent similarity in prevalence rates between cocaine and heroin use is likely to be a result of the nature of household surveys and under-representation of some members of the community.

The proportion of people who reported that they have ever tried amphetamines or hallucinogens was lower in Amsterdam compared to Australia and Victoria. In all countries examined, less than 1 per cent of those surveyed reported having used heroin within the last 12 months. Americans were more likely to ever have tried cannabis than Victorians, although a lower proportion reported that they had used in the last 12 months.

2.1.6 NATURAL HISTORY OF DRUG USE

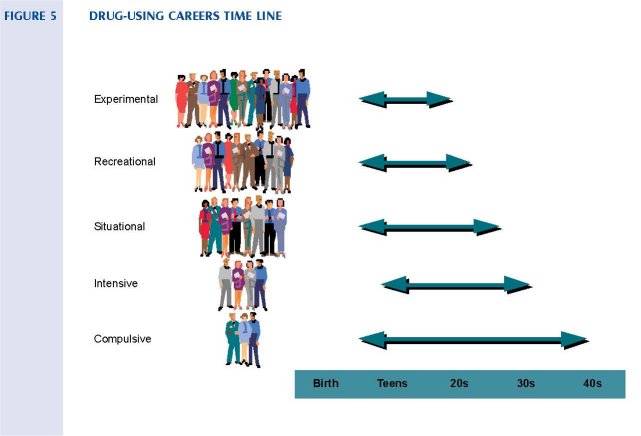

Drug users are generally divided into five major categories:

• Experimental users

• Recreational (or occasional) users

• Situational (or occupational) users

• Intensive (or binge) users

• Compulsive (or dependent) users

The majority of drug users do not progress from one group of use to another. However, of those that do, progression is generally related to:

• The route of administration: intravenous users are more likely to progress than oral users.

• Individual's characteristics: for example, those who use at a younger age are more likely to progress and a history of psychiatric problems is also associated with increased progression.

Most drug use is neither abusive nor problematic to the individual or the community and falls within the experimental and recreational patterns of use. The drug-using careers of these people is relatively short. Drug users in the intensive and compulsive categories are the least numerous, but on an individual basis, have the longest drug-use careers. Episodic abstinences and decreases in drug use appear to moderate the drug-using career. Lifestyle changes, such as employment and stable relationships, are correlated with cessation of drug use.

CANNABIS

The majority of cannabis use is experimental or recreational, and most people use the drug on a small number of occasions. They either discontinue their use, or use intermittently and episodically after first trying it. Among these people who continue to use cannabis over longer periods, the majority discontinue their use in their mid to late 20's. Only a small proportion of those who ever use cannabis use it on a daily basis over extended periods. Some 10 per cent of regular cannabis users develop dependence or complications from its use; a situation similar to that of regular users of alcohol. Daily users are more likely to be male and less well educated. They are also more likely to regularly use alcohol and have experimented with a variety of other illicit drugs.

HEROIN USE

The peak period of initiation of heroin use usually occurs in the late teens. Many individuals who commence heroin use continue to do so for a relatively brief period (weeks or months). Among individuals who develop a regular pattern of heroin use, 10 per cent have stopped by the end of the first 12 months, and a steady 2 per cent to 3 per cent of people are commonly found to be abstinent in each subsequent year. At the end of the a 10-year follow-up, 40 per cent abstinence from heroin is a typical finding. The remaining 60 per cent are accounted for by active drug use, imprisonment and death. The death rate in these studies is typically of the order of 1-2 per cent per year. Follow-up studies indicate a high-level of polydrug use, especially alcohol, in the group that became abstinent from heroin 10 years after first use (Heather et al, 1989). Heroin can be injected, smoked or sniffed. Experience in Europe suggests that when the price is high and relative purity is low, users tend to inject heroin. As the price decreases, users tend to smoke or sniff heroin.

AMPHETAMINES

Current trends indicate relatively high levels of experimental and recreational use of amphetamines among young people. There are also indications that experimentation with injecting as a route of administration is becoming more widespread (Hando and Hall, 1995). Amphetamines are also used by situational users such as long distance truck drivers, shift workers, and students who need to stay awake for long periods of time. Process workers may use amphetamines to relive the monotony of repetitive tasks. Athletes wishing to increase their energy, desensitise themselves from pain or even increase their aggressiveness may also use amphetamines (McAllister, 1991). Amphetamines can be injected or taken orally. Injecting amphetamines directly into the bloodstream increases the risk of harm to the user. These risks include a greater propensity of the user to succumb to bloodborne viruses.

COCAINE

Until recently, cocaine use was thought to be restricted to upper socio-economic levels, but it is increasingly being evenly distributed throughout the community. Cocaine users tend to be unmarried and also polydrug users. A recent study in Sydney found that there were two main subcultures of cocaine use: casual or recreational use among high socioeconomic status intranasal users, and more compulsive, serious use among lower socioeconomic status injectors. Ages for both types of users ranged from the late teens to about 50 years of age, although the typical user was aged between 20 and 40. Initiation was generally through friends, partners or work colleagues (Hando, 1995).

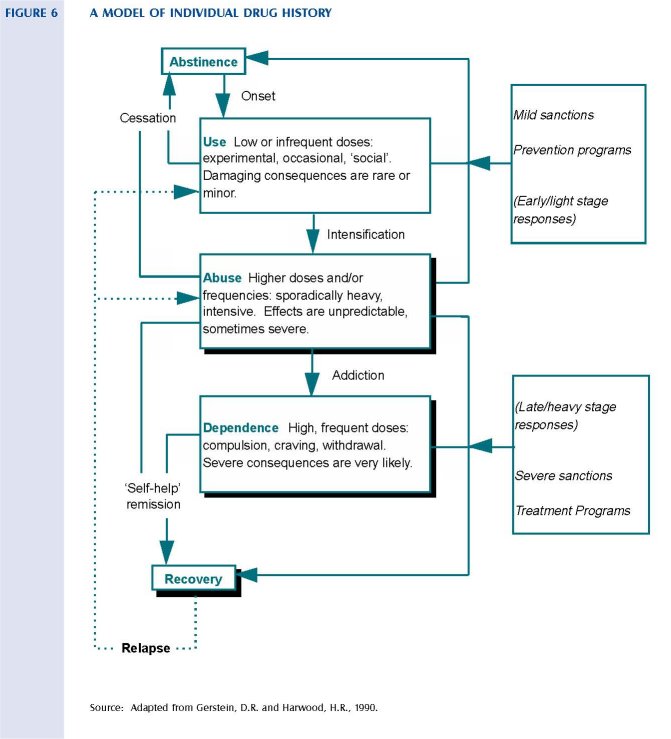

The above model shows the principal patterns or types of drug-taking behaviour. It groups them into common stages that, taken together, constitute a developmental pathway for individuals.

2.1.7 SOCIAL FACTORS

There are no reliable broadly based Australian studies that detail the social factors that contribute to illicit drug use. The relevance of international studies is limited as the social, cultural and political circumstances that prevail do not adequately relate to the Australian situation.

The factors which contribute to drug use are not clear. Many theorists suggest that psychological factors are the pre-eminent causes of drug use and abuse (West, 1991). Others have noted that the unemployed are over-represented in the numbers of those who have tried illicit drugs (Makkai, 1994). It is difficult to ascribe causal status in the development of drug abuse to socioeconomic factors. This is because not all people who have grown up in socioeconomically deprived circumstances go on to use drugs and commit crime. The reverse is also true: that some individuals from economically advantaged backgrounds have problems with substance abuse. However, the phenomena of youthful commencement leading to entrenched substance abuse often travels with a history of disordered relationships in the family of origin, socioeconomic disadvantage, and early and prolonged periods of homelessness (Spooner et al, 1995). The acceptability of drug use within any given society might also be a factor in determining the prevalence of drug use although evidence of a causal relationship is not to be found in the research literature.

Those who present to tertiary treatment centres or who become involved with the criminal justice system are usually economically impoverished and psychologically disordered. It is likely that those who come into treatment or the criminal justice system are there partly because the illicit nature of their addiction has led to, and maintained them in, a state of socioeconomic disadvantage. It is plausible therefore to suggest that substance abuse occurs within a matrix of socioeconomic disadvantage and emotional disorder. The origins of these substance abuse problems are often to be located in complex social and family risk factors and individual protective factors (Huba, Wingard, & Bentler, 1980; Sadava, 1987; Zucker & Gomberg, 1986).

Changes in the labour market, particularly as these affect young people first entering the job market, make a significant contribution to the sense of hopelessness many young people experience in relation to their future, as well as affecting their investment in society generally. Low-skilled jobs taken up by young people living on the fringes of society was historically an important means by which this group was integrated into society (Victorian Youth Affairs Council Submission, 1996). As greater emphasis is placed on the development of a highly skilled work force it is likely that these jobs are less available than has previously been the case.

The growth in the number of marginalised young people who comprise a chronic core of the young unemployed, almost certainly leads to an increasing probability that this group will initiate illicit drug use. If these factors are mediated by the influences of poor school achievement and diminished family support it is likely that emerging from this matrix of factors is a young person who has an increased likelihood of initiating and maintaining substance abuse (Ray & Ksir, 1990). The link between illicit drug use and crime means that this particular group of vulnerable young people are further marginalised.

2.1.8 PHYSIOLOGICAL AND PSYCHOLOGICAL EFFECTS OF DRUG USE

The effects of use of any drug vary from person to person, and vary on different occasions for the same person. The situation in which they are used can also influence the experience of the drug, and the effect of some of the drugs can be more variable than others.

The experience of most of these drugs for most individuals, at least in the early stages of use, is positive. This is the main reason people continue to use drugs. At later stages, some use is self-medication, where the user takes the drug to treat a drug withdrawal effect. There are only a few users who do not enjoy their use.

The immediate effects of a drug can be influenced by the following factors:

• The drug itself

Most of the drugs under review have a specific effect on various areas of the brain which, for some of the drugs, determines the subjective effect. This is not the sole determinant of the experience for any of these drugs. Some drugs, such as cannabis, have a range of effects and might be classified variously as a depressant or a hallucinogen.

• Drug strength

The amount and intensity of the active substance taken is significant in determining the effect. In general, a higher dose is more likely to produce more extreme effects (but this is not always the case).

• Drug purity

There are two ways in which mixing drugs or substances can influence the effect or experience of using a drug. First, some effects of drugs are due to the mixers or cutting agents used in preparing the substances and these can be very dangerous (for example, the use of talcum powder in cutting heroin). Second, drugs can be mixed by consumption of more than one drug at a time or over time. The pattern of poly or multiple drug use is common. While some users are experienced and deliberate in their mixing of drugs to enhance the effect of one drug or reduce the side effects of another, most use a range of substances in response to market phenomena or unreliable supply, and to treat the long-term effects of chronic use. The use of licit drugs such as alcohol and tobacco, as well as prescription drugs is common among long-term heroin users for example.

• Experience with the drug

Where a person has developed a tolerance to the drug, the effect of using the same quantity will diminish. Some of these drugs have a greater capacity to induce tolerance with prolonged use than others. This is one reason why users tend to continue to increase their dose over time. In other words, they need to use more to achieve the same experience.

• Route of administration

While injecting is the most efficient way of administering some of these drugs to achieve maximum effect for the amount available (and one reason why those who inject do so), other drugs are equally effective when taken orally.

• Expectations of the effect (sometimes known as ‘set’)

The effect of most of these drugs can be influenced by the learned and socially or culturally determined reputation that the drug has. If the user is expecting it to make them ‘high’, this significantly increases the chances that this is one of the effects that will be reported on use. The effects experienced on use of these drugs have been described as highly suggestible.

• Setting

Drugs taken in settings where the user feels safe and secure are less likely to produce anxiety reactions than the same drugs taken in unfamiliar settings. In addition, the behaviours that are associated with the use of the drug can influence the way in which it is experienced (for example, taking a drug at a dance or ‘rave’ party will be a different experience to taking it at home, as it is likely to be associated with intense dancing and physical activity, heat and sometimes dehydration).

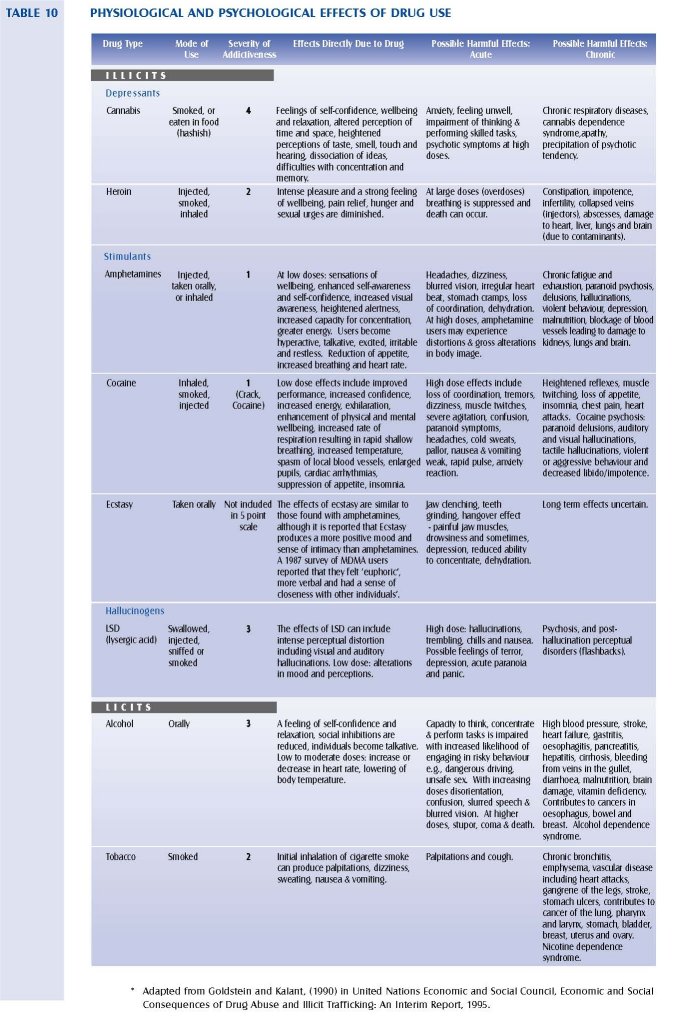

Table 10 outlines the immediate, acute and chronic effects of the major drugs under review by the Council. The effects of alcohol and tobacco are also presented here for comparison. Also included is the relative risk of addiction for these drugs, as outlined by Goldstein and Kalant (1995), on a five-point scale where 1 is the most severe. In this model, cocaine and amphetamines are seen as the most addictive of the psychoactive substances, and cannabis the least addictive. Falling between these in terms of addictiveness are the opiates (2), nicotine (2), alcohol (3) and hallucinogens (3).

A more detailed summary of the health effects of each drug type, including production, and mode of use, is provided in appendix 7. Also presented in appendix 7 is a comparative appraisal of the health risks of alcohol, tobacco and cannabis.

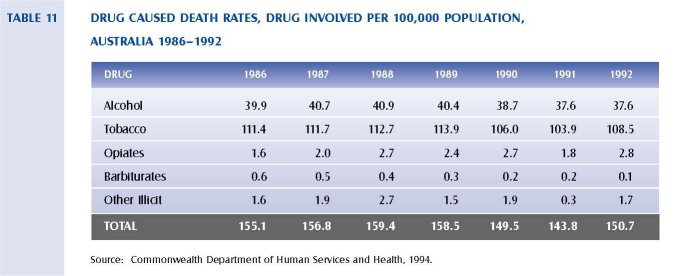

In Australia, the vast majority of deaths caused by drugs were as a result of the use of licit drugs: tobacco and alcohol. This is clearly demonstrated in table 11. An extremely small proportion of deaths is related to the use of opiates, barbiturates and other illicit drugs.

Any certification of death where drugs are considered to be the main cause of death is required to be reported to the State Coroner. The Victorian Institute of Forensic Pathology (VIFP) has provided the Council with information on the prevalence of illicit drugs in sudden and unexpected deaths in Victoria. Deaths are classified as being drug-related if the cause of death is, at least in part, attributed to the toxic effects of drugs. In some cases, the drugs will have been used as part of a suicide rather than reflecting continued misuse of drugs. The number of heroin-related deaths reported to the State Coroner increased markedly in 1995 and accounted for half of all drug-related deaths.

The proportion of all drug-related deaths that are heroin-related has increased over the last four years from 23 per cent to 49 per cent. This increase is a result of a decrease in non-heroin-related deaths, and a gradual increase in deaths attributed to heroin. The average number of heroin-related deaths per year is 86, or 1.9 per 100,000 population. Further statistics from the VIFP indicated that 78 per cent of heroin-related deaths are males, and that the mean age for males and females is 28 years. Only 15 per cent of all heroin-related deaths did not involve other drugs.

The prevalence of amphetamines in deaths reported to the Coroner has remained relatively steady in recent years. On average, 32 cases are detected each year involving amphetamines. Males account for 73 per cent of amphetamine-related deaths, and the mean age for males and females is 29 years. In Victoria, cocaine is rarely seen in deaths reported to the Coroner. Over the last five years there have been eight cases involving cocaine, four of which occurred in 1995. All cases were male and the mean age at death was 35 years.

Although marijuana is frequently detected in post-mortem specimens, its presence was not considered by the toxicologists as being a significant contributor pharmacologically to any death. However, its presence may contribute to the circumstances in which the death occurs; for example, in the case of fatal motor vehicle accidents.

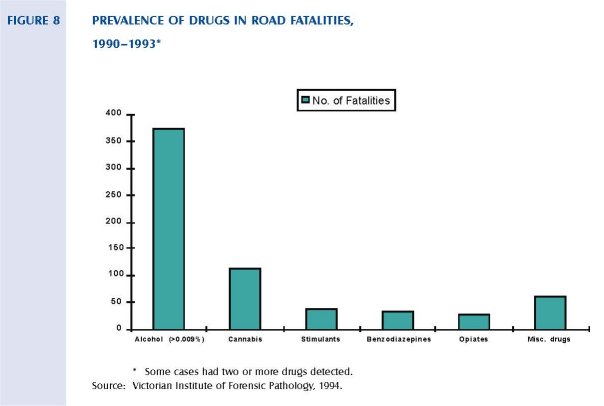

A study by the VIFP analysed the drug content in the blood of over 1000 drivers killed in accidents in Victoria, Western Australia and New South Wales over the period 1990 to 1993. It concluded that alcohol was involved in 36 per cent of deaths, and other drugs involved in 22 per cent of deaths. Figure 8 indicates the major drugs involved. The most frequent drug involved was cannabis, which was detected in 11 per cent of fatalities. It should be noted that the presence of some drugs can be detected in the body for extended periods well after use. In the case of cannabis, although the effect of the drug may last for a number of hours, it can still be detected in the body for up to six weeks after use.

2.1.10 COMMUNITY ATTITUDES

Public knowledge about drugs and drug use, as well as public attitudes toward a range of drugs, is highly variable. The National Drug Household Survey and the Victorian Drug Household Survey seek to provide an insight into public opinion, knowledge and awareness of both licit and illicit drugs. In addition, other public opinion polls often seek information on the publics attitudes to the legalisation of certain drugs.

Many members of the community use the terms decriminalisation and legalisation interchangeably. Results from public opinion surveys should therefore be viewed cautiously.

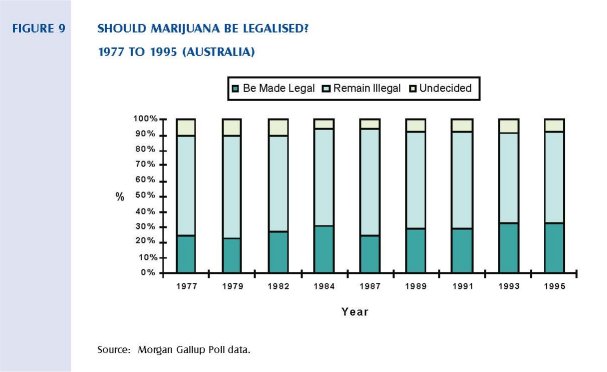

Morgan Gallop Polls have regularly polled public attitudes to the legalisation of marijuana since 1977. In 1995, 33 per cent of Australians polled supported the legalisation of marijuana; an increase from 24

per cent in 1977. The highest levels of support came from those aged between 18 and 24 years (45 per cent), and 41 per cent of those aged 25-34 supporting legalisation. In Victoria, 31 per cent of those polled supported legalisation.

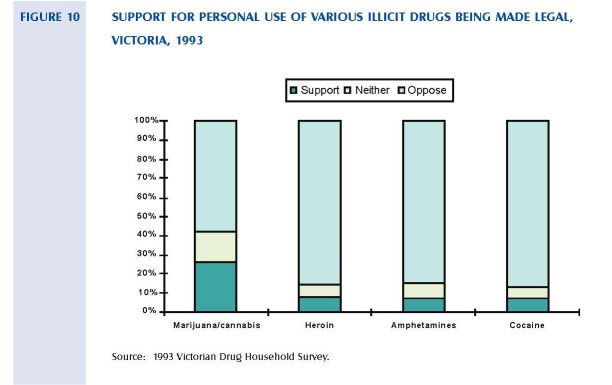

The Victorian Drug Household Survey asked people if they supported the proposal to make personal use of specific illicit drugs legal. Figure 10 shows the level of support for the legalisation of personal use of illicit drugs of those surveyed in 1993. Approximately 26 per cent supported legalising personal use of cannabis, while only 8 per cent supported legal personal use of heroin.

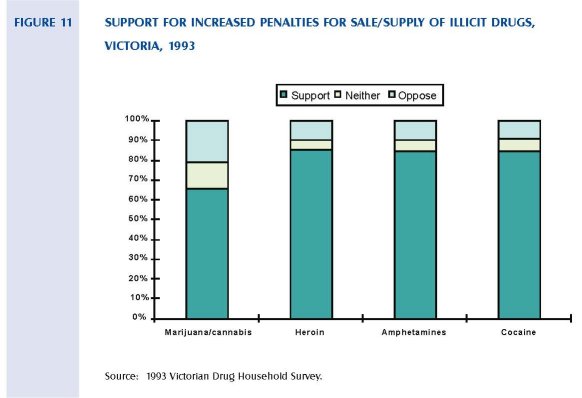

In relation to penalties for the sale or supply of illicit drugs, support for higher penalties was high particularly in the case of heroin, amphetamines and cocaine. Approximately two-thirds of those surveyed supported increased penalties for the sale or supply of cannabis.

2~.2. Detering Manufacture, Supply and Distribution

2.2.1 INTERNATIONAL CONVENTIONS

The Australian Government is a signatory to a wide range of international treaties. Several of these relate to illicit drugs and are relevant to the work of the Council.

International treaties related to illicit drugs reflect the concerns of many nations about the impact of these drugs. They are also a recognition of the fact that controlling the supply of these drugs requires international cooperation. The extent and nature of the international treaties has evolved over many years. The first such agreement was the 1912 Hague Convention controlling the manufacture of opium.

A number of conventions were signed after 1912 and included:

• The 1925 International Opium Convention.

- The 1931 International Convention for Limiting the Manufacture and Regulating the Distribution of Narcotic Drugs.

• The 1936 Convention for the Suppression of the Illicit Traffic in Dangerous Drugs.

• The 1946 Geneva Protocol that transferred functions exercised by the League of Nations under various narcotic treaties to the United Nations.

• The 1948 Paris Protocol that authorised the World Health Organisation to place under international control any dependence-producing drug, synthetic or natural.

• The 1953 New York Opium Protocol that limited the use of opium and international trade in it to medical and scientific needs.

The major treaties involving illicit drugs are:

• The 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs that Australia ratified in 1967. The convention defines the drugs covered (consistent with those that are the subject of the Council's terms of reference) and details the agreement that the trade and use of these drugs should remain illegal.

• The 1972 Protocol attaches to the 1961 Convention. The importance of this protocol is that it places greater emphasis on treatment, education and rehabilitation for abusers who commit minor offences as an alternative or adjunct to imprisonment.

• The 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances added synthetic hallucinogens, stimulants and sedatives to the list of banned drugs, and provided improved structures to distinguish medical use of drugs from other purposes.

- The 1988 Convention Against the Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances was ratified by Australia in 1993. This convention enhanced the provisions relating to inter jurisdictional cooperation in the detection and prosecution of drug trafficking. It sets standards for signatories in such matters as dealing with possession and purchase of illicit drugs.

The impact of these conventions on legislation and policy are the subject of continuing debate in Australia and internationally. While there is clear international desire that all the specified substances remain controlled and that their use be diminished or contained, regimes for managing their use and the treatment of users vary widely.

In Australia and several other countries, there is concern about the impact of the treaties on policy flexibility. The debate on the legal status of cannabis and the most effective way to reduce its use and misuse is perhaps the most visible focus of concern. The discussions in Australia and elsewhere about the merits of prescribing heroin would also test the requirements of the treaties. Discussion of these matters occurs in other sections of this report.

Legal opinions on these matters have been produced in the past. The opinions vary both because of the questions asked, and because the obligations arising from the treaties are capable of varying interpretations.

In the time available the Council did not seek any further legal opinions, nor was it seen as a necessary or appropriate course of action. This report details the legislative and policy directions that the Council believes are most appropriate. The Government will need to obtain advice on the specific options proposed.

2.2.2 STATE AND COMMONWEALTH LEGISLATION

Australian drug policy, prior to the 1960s, was largely determined by public servants and had bipartisan support. In general, drug use was condemned not only because of the perceived health risks involved, but also because of its lack of acceptance by the majority of the population. However, legislation enacted during the 1970s and 1980s reflected a major shift in focus, and the crime of possession was central to the structure of recent drug legislation (Manderson, 1992). Movements in legislation also reflected Australia's involvement in international treaties and conventions that became increasingly more important during the 20th century.

Manderson provides a useful history of drug legislation in Australia that is briefly summarised below:

- During the 19th century, the consumption of drugs (medical, quasi-medical and recreational) was largely a matter of personal choice.

• The Victorian Poisons Act 1876 provided that, in general, poisons had to be sold by either a doctor or chemist and had to be labelled `poison'. There were few controls on who could purchase them and for what purpose they were used. Self-prescription of opium and laudanum (an opiate) was prevalent. Around this time, Australia had the highest per capita consumption in the world of patent medicines, whose secret active ingredients were principally alcohol or opiates.

• The first drug laws in Australia were enacted at the turn of the century to prevent opium smoking. The laws were not based on a belief that addiction was unhealthy or immoral, but rather were racially based. At this time, the smoking of opium was a primarily Chinese habit and racism was an important element of political life in Australia.

- The first law prohibiting the smoking of opium was enacted in South Australia in 1895 and all other States had followed suit by 1908. This was linked to community attitudes to Chinese immigrants.

- In 1905, the Commonwealth proclaimed that the importation into Australia of opium in a form suitable for smoking was 'prohibited absolutely. However, these laws did not deal with the opium contained in patent medicines, nor with its common and frequently habitual consumption in the form of laudanum.

- These laws formed the precedent for later laws that developed through the 1920s and 1930s and restricted the use of drugs such as heroin, morphine and cocaine. They were largely a response to international and bureaucratic pressures, rather than a conscious determination to create a comprehensive system of control over an ever-expanding range of drugs.

• The large number of treaties to which Australia became subject committed Australia to the prohibitionist approach advocated by the international community under the leadership of the USA. As a result of this pressure, the Commonwealth expanded the 1905 proclamation dealing with opiumin 1914 to deal with a range of other drugs covered by the Opium Convention of 1912. The importation of these substances was not prohibited absolutely, but was made subject to certain restrictions designed to ensure that they were used for 'medicinal purposes only.

• State legislation also expanded to prohibit morphine, cocaine and heroin. In 1913, Victoria legislated that these drugs could only be available through a written prescription, or the order of a duly qualified medical practitioner. Regulations concerning various 'dangerous drugs' were introduced in 1922, and created a complex system of licences and authorisations. They penalised not only sale without a prescription but also possession. These laws were later put into the body of the Poisons Act.

• International pressure continued to expand the range of drugs that were legally available only with medical authorisation. Before and after the Second World War, Australia had very high levels of heroin consumption. By 1951 it recorded the highest per capita level of use in the world. Internationally, pressure for the complete prohibition of heroin grew.

• In 1953, the Commonwealth acted to prohibit absolutely the importation of heroin and began to pressure the States into enacting parallel legislation prohibiting manufacture, use and possession. As a result, all States prohibited the manufacture of heroin, although Victoria did not make the possession of heroin illegal, although heroin was legally unobtainable.

• Laws against cannabis were passed, although in the 1940s and 1950s its use in Australia was almost unknown. In 1940, the Commonwealth extended import controls over Indian Hemp, and its extract and tincture, to include preparations made using it. In 1956, the Commonwealth absolutely prohibited the importation of cannabis into Australia.

• In 1981, the Drugs, Poisons and Controlled Substances Act 1981 (the act) replaced the Poisons Act in Victoria.

The Act sought to provide a framework for the protection of the public from the harm that could follow from the misuse or abuse of drugs and poisons that came under the control of the Act. The Act regulates the availability of drugs and poisons to those who need them and are equipped to handle them. With some substances, special facilities or training may be necessary for their safe use.

The Guide to the Drugs, Poisons and Controlled Substances Regulations 1995, published by the Department of Health and Community Services (H&CS), states that:

"The Act regulates the availability of drugs and poisons by:

(a) classifying drugs and poisons via a Poisons Code into different schedules, each of which represents a different level of availability; and

(b) establishing a system of authorising, licensing and permitting according to profession or activity; that is to say:

(i) authorising medical practitioners, pharmacists, veterinary surgeons and dentists to possess, use and supply;

(ii) licensing persons to manufacture and supply or to supply; and

(iii) permitting persons to possess and use for particular purposes, for example, industrial, educational or the provision of health services."

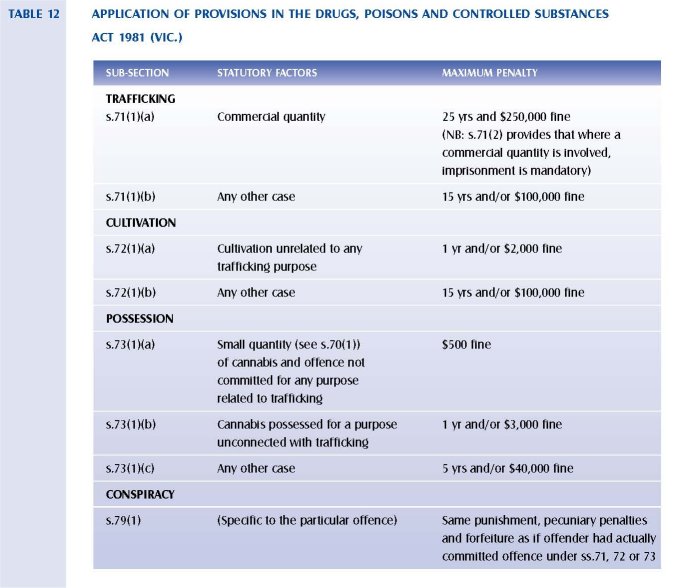

Maximum penalties for Victorian drug offences contained in the Act are outlined in table 12. As is the case with Commonwealth offences, the penalty range open to a sentencer is contingent upon certain statutory factors.

Other pertinent Victorian legislation includes:

• Bail Act 1977

• Crimes (Confiscation of Profits) Act 1986

• Road Safety Act 1986

• Sentencing Act 1991

• Summary Offences Act 1966

Relevant Commonwealth legislation includes:

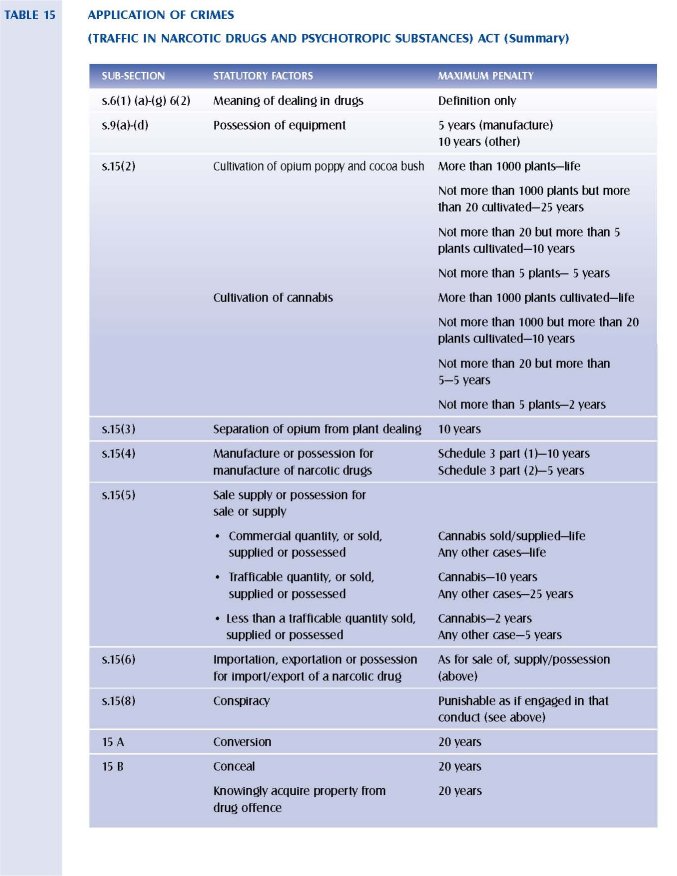

• Crime (Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances) Act 1990

• Customs (Prohibited Imports) Regulations

• Customs Act 1901

• Narcotic Drugs Act 1967

• Therapeutic Goods Act 1989

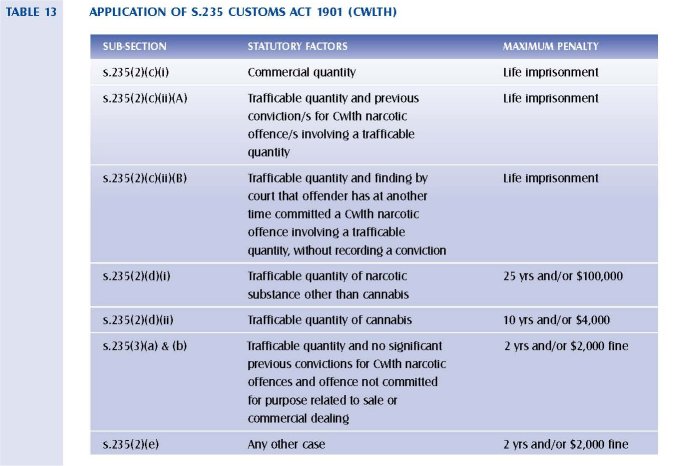

The statutory factors and maximum penalties included in the Customs Act 1901 are detailed in table 13.

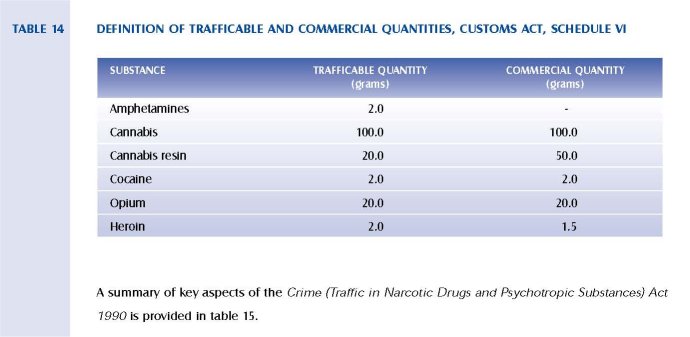

The trafficable quantities vary for each specific drug under Schedule VI of the Customs Act and are outlined in table 14.

2.2.3 LAW ENFORCEMENT

Law enforcement measures are recognised as an important strategy in minimising the harmful effects of drugs on Australian society. Policing is one of several law enforcement measures used to reduce the level of use of illicit drugs. It ranges from the investigation of drug trafficking and importation by the Australian Federal Police and the Australian Customs Service to police activities at the community level dealing with problems arising from illicit drug use. The roles and functions of the major law enforcement agencies are outlined in appendix 8.

The Department of Justice, in its submission to the Council, advised that official police statistics on drug offences are dependent on the level of policing activity and the priority given to an area. For this reason, any increase or decrease in police recorded drug statistics is less likely to reflect changes in actual levels of drug use in the community than the priority given by police to drug-related offences and/or their efficiency in detecting and apprehending drug offenders. As a result, the Department of Justice advises that caution is taken in interpreting the police statistics for drug offences, as they are, like crime statistics generally, subject to a variety of influences, many of which are unrelated to the actual level of crime in the community.

The number of drug seizures and the type and weight of drugs is one indicator of the availability of drugs. The Australian Customs Service reported to the Council that 6831 kilograms of illicit drugs were seized at the Australian border during 1994–95. These comprised 6520 kilograms of cannabis, 295 kilograms of heroin and 16.5 kilograms of cocaine. The amount of heroin seized constitutes a substantial increase on the amount seized in 1993–94 (54 kilograms) and 1992–93 (53 kilograms).

There has been a consistent decline in the number of drug seizures by federal agencies in Victoria, New South Wales and Western Australia since 1990–91. The decline in the number of seizures in Victoria is largely due to the reduction in cannabis-related seizures. All other categories of drugs have not shown a major change over this period in terms of number of seizures, although the weight involved has fluctuated.

In 1994–95, there were 9291 drug seizures by Victoria Police. Of these, 75 per cent were of cannabis, 12 per cent of amphetamines and a further 8 per cent of heroin. Smaller numbers of seizures were made for cocaine, LSD, Ecstasy and other drugs.

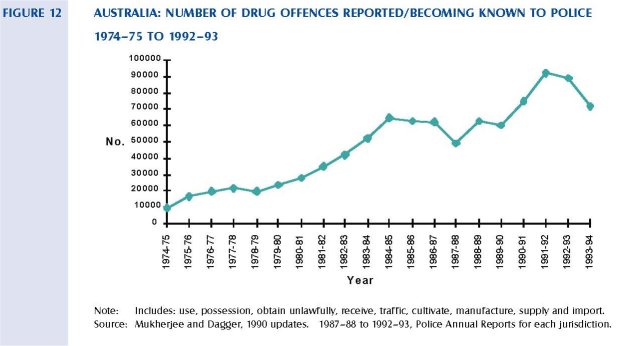

Police statistics indicate that the volume of recorded drug offences has increased over the last 20 years.

The number of drug offences reported or becoming known to police throughout Australia from 1974–75 to 1993–94 is presented in figure 12.

It should be noted that many of the variations identified here reflect changes in enforcement practices as much as changes in patterns of drug supply and use. The trend over the same period for Victoria shows that number of drug offences per 100,000 population has also significantly increased. The rate of recorded drug offences has increased tenfold from 52.5 in 1974–75 to 542.0 in 1992–93.

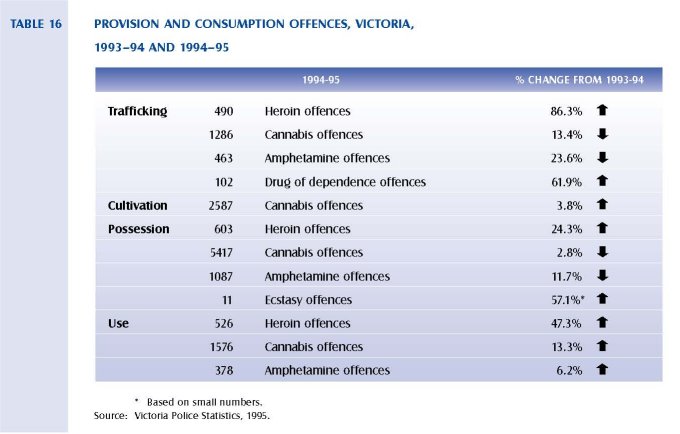

Police record drug offences for statistical purposes in terms of two categories: those involving possession and use of the drug (drug consumption), and those involving the cultivation, manufacture and trafficking of drugs (drug provision). Key statistics were provided to the Council from the Victoria Police relating to provision and consumption offences. They are presented in table 16.

In terms of drug offences recorded by the police, cannabis is the overwhelming drug involved in drug provision (81 per cent in 1994–95) and drug consumption offences (68 per cent in 1994–95).

Amphetamines accounted for approximately 8 per cent of provision offences and 14 per cent of consumption offences. Heroin also accounted for 8 per cent of consumption offences, and 11 per centn of provision offences.

Heroin offences, for provision and consumption, showed the only significant change between 1993–94 and 1994–95. In 1993–94, heroin offences accounted for 5 per cent of all provision offences and 8 percent of all consumption offences. In 1994–95, the proportion of heroin offences increased to 8 percent of all provision offences and 11 per cent of all consumption offences.

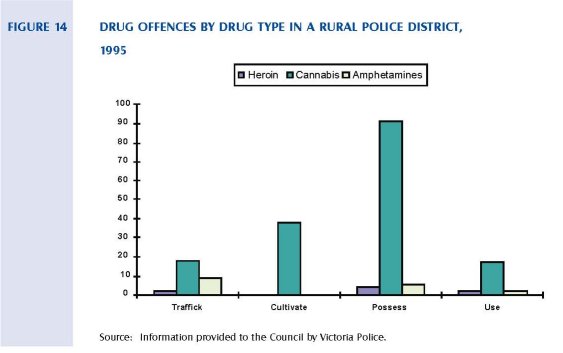

Drug offences for a typical rural police district in Victoria are outlined in figure 14. The vast majority of charges relate to cannabis offences and reflect law enforcement practices in many rural areas.

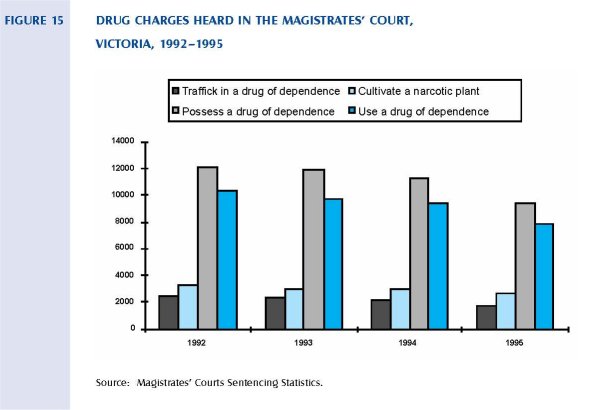

The offences of possessing a drug of dependence and using a drug of dependence are the third and fifth most frequent specific charges in the list of the top 100 charges heard in the Magistrates’ Court. When individual offences are broadly categorised into property, driving, drugs, personal crime and other, the drug offence category is third most frequent after property and driving offences. However, it should be noted that many property offences are drug-related, even though not recorded as such in the readily available statistics.

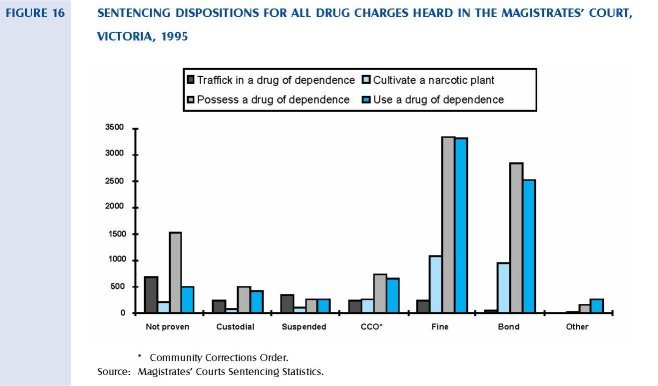

The four major drug charges heard in the Magistrates’ Court are trafficking in a drug of dependence, cultivating a narcotic plant, possessing a drug of dependence, and using a drug of dependence. Figure 15 compares the number of drug charges heard for each of these categories from 1992 until 1995.

It is clear that the vast proportion of drug charges heard relates to possession and use of a drug of dependence, rather than trafficking or cultivation offences. Sentencing dispositions vary according to the type of charge heard. Possession, use, and cultivation of a drug of dependence are most likely to result in a fine or bond. Trafficking charges are more likely to result in a custodial or suspended sentence. A high proportion of trafficking charges is not proven. In 1995, 38 per cent of all trafficking charges were not proven in the Magistrates’ Court.

The majority of defendants convicted of a drug offence in the higher courts receive a term of imprisonment. This proportion has remained relatively stable from 1991 to 1995. Fines and bonds are used infrequently for drug offences finalised in the higher courts (whereas they are the most likely penalty to be imposed for drug offences in the Magistrates’ Court).

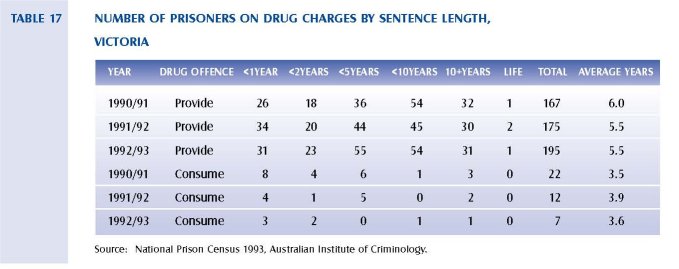

When the expected sentence length is computed for each drug offender, prisoners with drug provision offences as their most serious offence serve approximately five years in custody. Prisoners with a drug consumption offence as their most serious offence serve approximately 3.6 years in custody. These figures should be treated cautiously because of the averaging process and the small numbers involved. The distribution of sentence lengths for drug providers has not changed significantly over the period from 1990–91 to 1992–93. However, there has been a decrease in the overall numbers of prisoners on drug consumption charges over this period, while the number on provision charges has increased. The number of prisoners serving sentences of over 10 years for drug consumption charges may reflect the tail end of earlier sentencing policy.

A study of male and female sentenced prisoners in Victoria found that 69 per cent of those sampled were diagnosed as having a lifetime diagnosis of dependence on or abuse of alcohol, other psychoactive substances, or a combination of these (Herman, McGorry, Mills and Singh, 1991). In this context, a lifetime diagnosis refers to a diagnosis that has been sustained over time. Other studies have also found high levels of prior drug use among prisoners. Miner and Gorta (1987) found that 79 per cent of women prisoners in their sample reported prior drug use, and heroin was the drug most commonly mentioned.

2.3 Preventing Use and Reducing Harm

2.3.1 Community Education and Information

The Commonwealth, Victoria or any other State has not implemented a sustained effort to communicate with, inform or educate the community about illicit drugs. In Victoria, few resources have been allocated to the provision of community education and information programs in relation to drug use. Those that have been conducted have had a strong focus on licit drugs, especially tobacco, alcohol and prescription drugs. Table 2 indicates that of the $103 million spent on addressing illicit drug issues in Victoria in 1995, only $1.6 million was spent on prevention/education and information activities.

Key elements of community education strategies include information provision, media campaigns, sponsorships, school-based drug education, print resources and community development. There is very limited knowledge of which approaches to community education provision work. This is due to a lack of disciplined evaluations against which to judge the effectiveness of various strategies. These evaluations are in fact difficult to conduct. The overriding principle of drug education is that there is no one response to addressing the illicit drug problem through campaign information and education activities and that any strategic response must be multifaceted, integrated, coordinated and

sustainable.

There are a range of audiences and target groups that might usefully be identified in thinking about drug information and education. They are:

• Members of the general community including specific subgroups that may warrant specific attention, such as people of other language and cultural groups and people from regional and rural Victoria.

• Community leaders, including religious leaders.

• Professionals to whom drug users and their families turn to for advice and support, including:

• Generalist health and welfare professionals such as general practitioners, and nurses; those especially well placed to provide information, education and early interventions, such as youth workers.

• Those whose work involves them being in contact with drug users, such as police and ambulance officers.

• The law makers and those charged with its implementation, such as politicians, magistrates and those working in public administration.

• Specialist alcohol and drug personnel.

• Parents and friends.

• Young people.

• Those contemplating using drugs.

• Users: those who are already experimenting with, or regularly using, various drugs.

COMMUNITY INFORMATION

The community obtains information about drugs from a variety of sources; some are accurate, others are inaccurate. The mainstream media are prime providers of drug information to the community. They rank ahead of health, welfare and education services and personnel.

Analysis of content and style of reporting of legal and illegal drug issues was conducted by the Australian Drug Foundation in 1990 and replicated in 1994. In brief, this indicated that illicit drug matters were reported far in excess of their usage and 'harm levels'. Often this reporting was inaccurate and sometimes dangerous. It was usually sensationalised, particularly through headlines.

Strategically, it is crucial to maximise the reach and impact of the media as a source of drug information. At the same time it is important to understand the motives for the type of reporting of different drug issues.

Drug use can be affected by media reporting. For example, research has shown a direct link between media reporting of inhalant use and increased usage among young people; especially where the report includes naming products that can be used or includes diagrams and symbols which show use.

To enhance the level of knowledge and to inform community debate, the availability of accurate information is essential.

Sources of drug information include the media, printed and other information at specifically targeted venues such as waiting rooms in health services, and information available at needle syringe exchange programs.

Where people actively seek information, initial contact is usually made by telephone. Written material can often be an adjunct to verbal advice, information, counselling or referral.

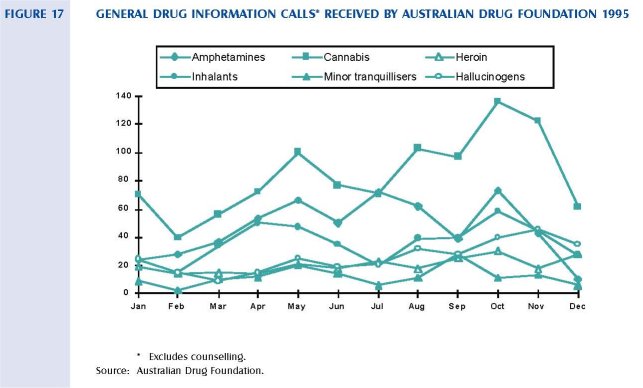

Figure 17 shows the number of general drug information calls received by the Australian Drug Foundation by drug type during 1995. Information requests for cannabis and heroin appear to have peaked around May and October, but care is needed in interpreting these figures.

Community information services are provided by the Australian Drug Foundation's Info Service, which provides information to the general community about drugs and which is strongly linked to a comprehensive specialist alcohol and drug library. DIRECT Line 24 hour telephone information, counselling and referral service provides the general community with information about drug use, counselling and support services and referral to alcohol and drug services. The Drug and Alcohol Clinical Advisory Service (DACAS) provides general practitioners and other generalist health and welfare professionals with advice and information on the clinical management of alcohol and drug problems. DIRECT Line, DACAS and Drug Info provide for regional and rural residents through the provision of a Freecall (1-800) number. Each of the above services are well utilised by the general community, as well as by a range of professionals working in the alcohol and drug and allied fields.

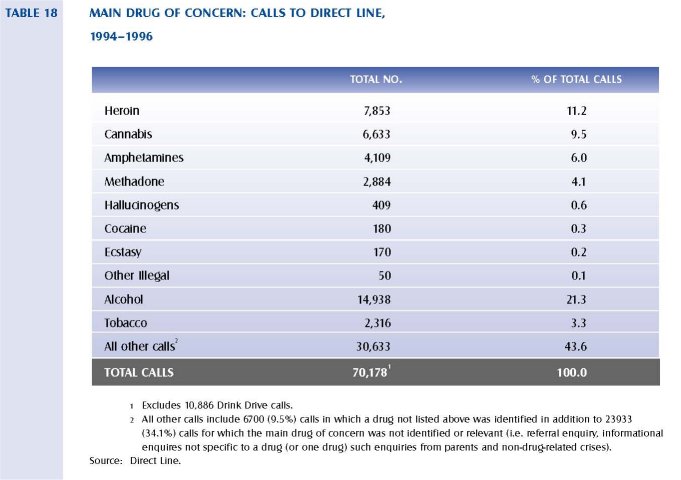

Information received from DIRECT Line indicates that it receives an average of 41,000 calls per year. Seventeen per cent of these calls are from people living in regional and rural areas of Victoria. Calls to DIRECT Line from 1994 to 1996 by the main drug of concern are detailed in table 18.

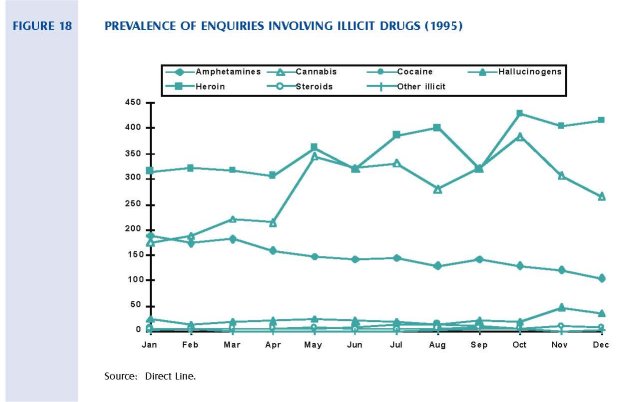

Figure 18 shows the prevalence of enquiries involving illicit drugs during 1995 to Direct Line. The number of calls relating to hallucinogens, steroids and other illicit drugs is relatively low and stable throughout the year, while calls about amphetamines declined. The majority of enquiries about illicit drugs relate to heroin and cannabis.

A number of generalist telephone services, such as Life Line, who receive a total of 30500 calls a year and Aids Line, include calls about drug use. However, the way data is collected by these services makes calls relating to alcohol and drug issues difficult to quantify. Information about drugs is also freely available on the Internet from a variety of sources. There is currently no way of ensuring that the information provided is accurate.

DRUG EDUCATION IN SCHOOLS

Schools are a natural site for drug education, as they offer access to the whole cohort of adolescents up to the school-leaving age of 15 years (and in many cases up to 17 years as the majority of students now complete Year 12).

The Drug Education Strategic Plan 1994-1999 guides the provision of drug education in Victorian schools. It was formulated under the aegis of the Directorate of School Education (DSE) in consultation the with Catholic Education Office, the Association of Independent Schools of Victoria, the Australian Drug Foundation, QUIT and Victoria Police. The plan seeks 'to enhance and sustain drug education in order to contribute to the minimisation of harm associated with drug use by young people'.

Over the past five years, a range of drug education materials and programs has evolved. These have been funded both from national and state government programs, and a range of community-based organisations and individuals. There appear to be no evaluations of the specific provision of information in Australia.

Evaluation of school drug education programs has been a focus overseas and elsewhere in Australia for some time. Evaluation results suggest that approaches which may appear appropriate to the lay person may not always be so. Evaluations of Victorian education programs have emerged particularly in the past five years. In the early 1970s efforts to dissuade young people from using drugs showed them the 'terrible troubles' that drugs could cause. These were the scare tactic campaigns. These programs sometimes included testimonials of ex-users describing their life when using drugs. Evaluation research found that many of these programs actually increased the likelihood of young people using drugs.

Moving away from this approach, the late 1970s saw drug education directed at personal development, such as enhancing self-esteem and decision making, and there was no mention of the drugs themselves. Evaluations of this approach produced varied results.

Findings from research and evaluation have helped improve knowledge about appropriate and effective drug education. It is likely that the educational approach to different drugs will vary according to a number of factors including their legal status. There is a suggestion that direct discussion of drugs that are legal and commonly available needs to be approached differently to the provision of information and education about illicit and rarely encountered drugs.

Consistent with guidelines suggested by the National Initiatives in Drug Education (NIDE) project, which aims to increase and improve drug education for school aged young people, the DSE has recently completed the development of Get Real. This package provides a resource that allows schools to respond to drug education from a policy, curriculum and welfare perspective within the health and physical education section of the curriculum, sequentially across the school years from Prep to Year 10. There is, however, no obligation on schools to undertake drug education or to use the resource material provided.

Council has been made aware of the efforts of some government and independent schools to provide drug education. During the consultations, representatives of some schools involved in the development of Get Real told Council how positively it had assisted their school.

Victoria Police also briefed the Council on its Police Schools Involvement Program (PSIP) in which 80 officers trained in harm minimisation work in schools across the State. Drugs and alcohol is one of seven modules delivered to students. A major role of the PSIP is on improving attitudes toward police. Australian Drug Foundation (ADF) research indicates that the program is effective with respect to alcohol and drugs if the officers have been trained and when their work is integrated into broader school programs.

Representatives of other schools and community groups with an interest in education talked about the efforts to provide drug education through visiting programs, and through written and other resource material. The Council has been provided with copies of some of this material. Some of these initiatives are large statewide programs one-off, visiting inputs, such as Life Education Centres. Others are local efforts initiated by concerned citizens. No detailed description of the extent and nature of these initiatives has been possible in the time available to the Council.

PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT

The potential role that health and welfare professionals can play in any drug strategy has long been recognised. Generalist health and welfare professionals are regularly responding to ongoing drug issues and related crises.

This group includes medical workers (GPs, hospital doctors and nurses), welfare personnel workers, employment officers, supported accommodation and assistance (SAAP) workers and youth workers. Their interaction with clients at a time when they are concerned or are experiencing problems with their health or lifestyle provides a unique opportunity to deliver information, and to educate the client and their family about illicit drug issues. It is also an invaluable opportunity to provide an early intervention.

A comprehensive, national report was prepared on the training needs of an extensive set of professional and other groups who are involved in delivering services to alcohol and drug users in 1986 (Commonwealth Task Force on Training, 1986 and 1987). A National Centre for Education and Training in Addictions (NCETA), has been established in South Australia and has links to Victorian organisations.

Some drug and alcohol specialist education opportunities are currently available and national courses offering distance education can be accessed, however, these cater for only a small number of students.

Police and teachers are also in a prime position to provide information, education and early interventions to young people. Preservice and ongoing professional development in current issues, policies and practice, contribute significantly to effectiveness.

In-service training and professional development of generalist health and welfare workers is currently minimal and ad hoc. The level of preservice training available to key professional groups is also variable. Under the current redevelopment of alcohol and drug services in Victoria, $1 million has been allocated for the provision of training for generalist health and welfare workers, but this program is still in its early stages.

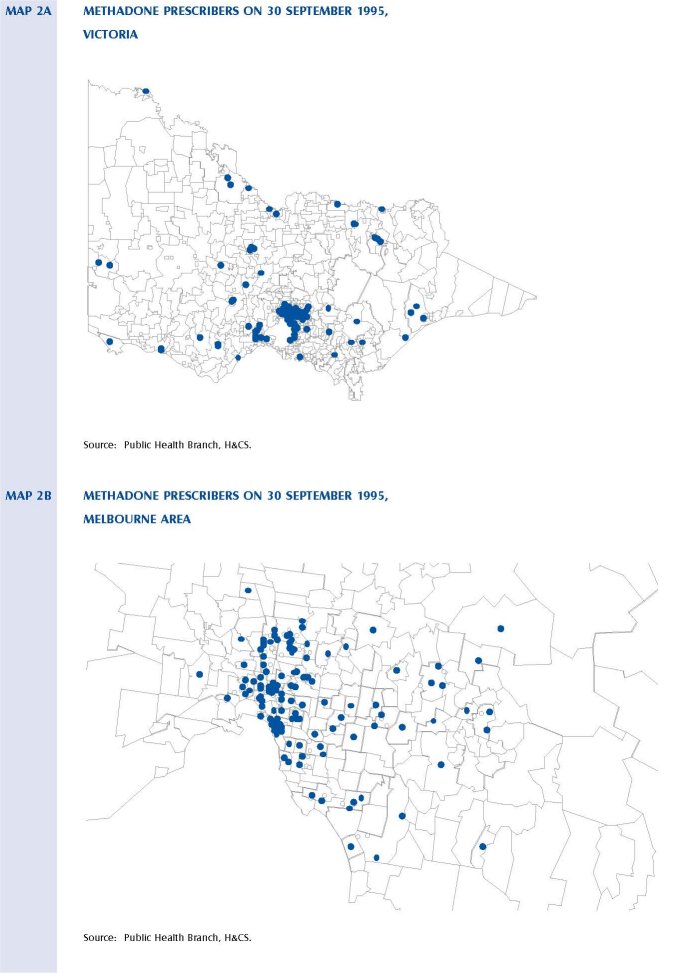

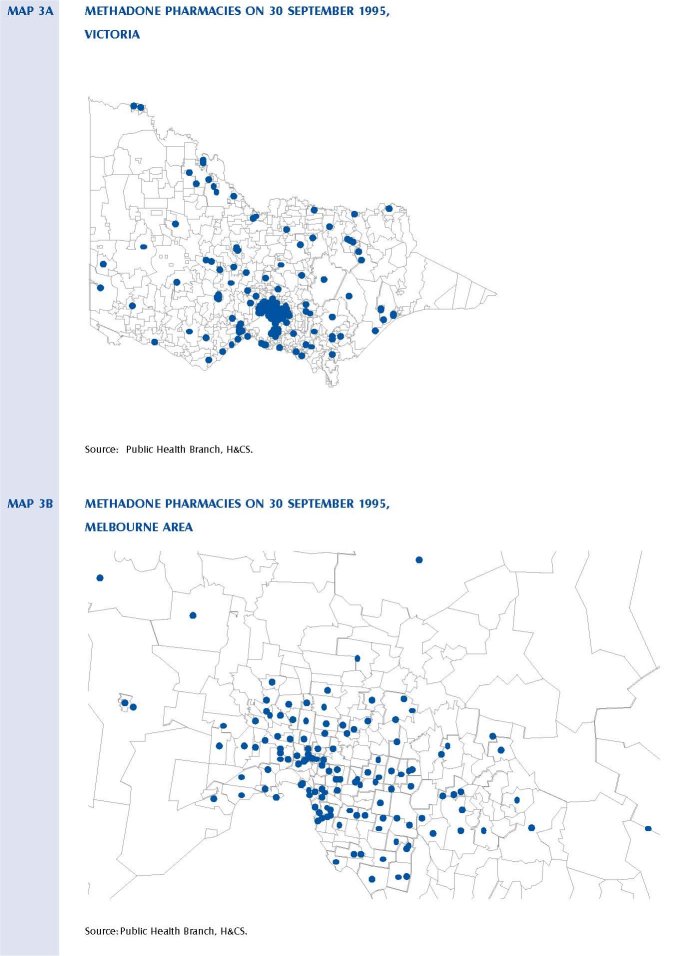

The Victorian Medical Post Graduate Foundation (VMPF) has also received funding from the Department of Health and Community Services (H&CS) to provide training for methadone prescribers through the Methadone training program and Prescriber Forums, in conjunction with the Turning Point Alcohol and Drug Centre. The training program aims to increase skills of methadone prescribers in identifying patients who are suitable for methadone, in assessing procedures for the safe prescribing of methadone, and in managing methadone clients within a context of long-term harm minimisation. Prescriber Forums are conducted every quarter and aim to meet some of the needs for ongoing prescriber education.

MEDIA CAMPAIGNS

Few major media campaigns have been conducted that address illicit drug use. The two most recently conducted in Australia were the Speed Catches Up With You Campaign in 1993-94 and Heroin Screws You Up in 1987-88. Evaluations of these and other media campaigns have been equivocal at best. This is consistent with evidence relating to campaigns in other countries. Miller and Ware (1989) conducted a thorough review of the effectiveness of media campaigns and concluded that they have an important role to play in providing an information base that would predispose the community to be receptive to other drug control strategies. Mass media campaigns should be viewed as one plank in a platform of strategies required to effectively address the problems associated with alcohol and other drug use, and are probably less appropriate for illicit drugs than for licit drugs (Miller and Ware, 1989).

COMMUNITY INVOLVEMENT

Drug issues are issues for the whole community. Community involvement strategies can aim to change structural, environmental, and social factors that contribute to drug use and drug harms. They often require the support of a dedicated worker who is skilled in working with divergent groups, and who has an understanding of community development principles and processes.

A small number of local councils are supportive of this approach and have provided submissions and verbal presentations to Council describing their current or proposed local projects. One example of community involvement is the St Kilda Project in the City of Port Phillip. This project has been in operation since 1991 and aims to reduce the negative impact of alcohol and other drug issues on the life of the St Kilda community through a process of community consultation, participation and education, and through the development of specific projects. Independent task groups and special project groups are developed to address specific issues in the community. A coordinated approach is encouraged through the interaction of task groups on activities and initiatives. This project is currently being evaluated.

The City of Greater Dandenong and the Victorian Department of Justice jointly fund a Safer Communities Project. This project aims to build partnerships between police, council, and the community to identify, develop and implement community safety initiatives. The strategy encompasses broad community safety and crime prevention issues (such as urban design and planning safer communities, violence prevention, community education), and interaction with educational institutions and youth specific drug and alcohol and health initiatives.

The Westgate Drug Task Force has been established to address the drug problem that has escalated in the western suburbs of Melbourne. The task force has representatives from regional Police Community Consultative Committees that include local community representatives and police. The task force's proposed strategies to address the drug issue in the western suburbs include, an integrated public education program, and a drug and violence assistance unit. It combines the resources of Victoria Police, local government and H&CS.