6. American Heroin Policy: Some Alternatives

| Reports - Drug abuse council report |

Drug Abuse

6. American Heroin Policy: Some Alternatives

Erik J. Meyers

The author gratefully acknowledges the contributions of the following individuals in preparing background materials for this chapter (However, the opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of these contributors): Leon G. Hunt, Troy Duster, Jane McGrew, Charles Morgan, Jr., Hope Eastman, Norman Siegel, and Gerald F. Uelman.

THOUGHTFUL OBSERVERS OF the American drug situation have frequently stated the belief that our problems may be caused more by our policies than by the drugs they seek to regulate. As one writer has commented, the United States may have "created a monster out of what was initially a gnat" in moving from a nineteenth-century laissez-faire approach to drugs to a twentieth-century preoccupation with eliminating use of certain drugs.' If we look at present studies on the "social costs" of drug use, we see that they examine more the costs of present drug policies to American society than the intrinsic social costs of drug use itself. Nowhere is this dilemma over drug policy more clearly shown than in our national response to heroin use.

The discussion of alternative heroin policies that follows is meant to stimulate and focus public discussion of drug policy. We hope to promote reasoned, nonrhetorical consideration of the nature of the problems and the most appropriate means of minimizing social disruption and harm to individuals. While no policy will eliminate all problems, our analysis shows that some policy responses are more likely than others to minimize detrimental effects. This discussion begins with a look at the full spectrum of policy choices available and at specific policy models along that spectrum. Following that, we will examine the key issues heroin policy must deal with, in terms of four selected policy choices.

Our list of potential policy choices ought not be viewed as a serial progression, nor does this identification of separate, individual options necessarily preclude the adoption of more than one at a time. Implementation of one option may preclude others or instead stimulate consideration of others. The policy choices examined in the following discussion are merely illustrative of the existing possibilities; they are not intended as a complete and final list nor as a timetable for change.

The Choices

The range of possible heroin policy options is wide, extending from efforts to prohibit and eliminate all types of heroin use to official promotion of nonmedical heroin use by means of a government monopoly. The shades of difference within this spectrum of policies are nearly infinite. For example, a heroin policy could be fashioned to subject illicit sellers and distributors to criminal penalties while levying only small civil fines on those possessing small amounts of heroin for their own use. Another approach would be to subject all convicted users to long, mandatory jail terms, with lifetime parole. Both of these approaches are consistent with a policy seeking to deter use and ultimately eliminate consumption, in spite of their obvious differences in the means employed to achieve these goals. Other possible heroin policy choices falling between the poles of stringent prohibition and totally unregulated sale and consumption are: experimental use of heroin in medical and drug treatment research, development of government-sponsored heroin treatment clinics, removal of criminal penalties for personal possession, prescription of heroin by private physicians, regulation of heroin as an over-the-counter drug; and development of a "pure food and drug" model for distribution of the drug.

Complete Prohibition.

This is current American policy, in which laws provide criminal penalties for the possession, use, sale, and distribution of heroin. Federal law and a few state laws treat possession as a misdemeanor (maximum penalty: one year in jail), while other jurisdictions treat it as a felony. All jurisdictions treat sale and distribution as felonies (more than one year in jail), though penalty provisions as to fines and terms of imprisonment vary widely.

Many jurisdictions provide for the diversion of certain classes of heroin offenders into treatment programs. Successful completion of a treatment regimen may result in the dropping of pending criminal charges or may be considered evidence of rehabilitation at sentencing. Failure in treatment returns the offender to the normal criminal justice process for trial and sentencing if found guilty.

In practice, many urban criminal justice agencies do not attempt to fully enforce laws against personal use or possession of heroin. For these jurisdictions, "total prohibition" means that occasional "sweeps" may be made in areas where use levels are high or that the laws may be used selectively to punish some users while others are ignored. Conversely, many jurisdictions do not have a great many heroin users, and are inclined to arrest and fully charge every heroin offender who is apprehended.

Medical and Drug Treatment Research with Heroin.

Current federal law does not permit heroin to be prescribed for legitimate medical purposes or for "maintenance" treatment of compulsive users. The only permissible use is for certain highly restricted research projects. For example, heroin was used several years ago to test the effectiveness of narcoticdrug antagonists. However, recent interest from the medical community and segments of the general public in using heroin to alleviate the pain associated with certain types of cancer could play a role in ending official reluctance to permit research into therapeutic applications for the drug.2 Still, despite interest in the scientific and medical communities to test the efficacy of heroin as an analgesic, an antitussive, or as a tool in opiate addiction treatment, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA)—the agencies whose administrative approval is required—have discouraged heroin research. It is because these agencies have been so reluctant to allow research with heroin that we have identified medical and drug treatment research as an independent policy option.

Our further discussion of this option below pertains to experimental research into drug abuse treatment applications for heroin, rather than to investigation into other medical uses for the drug. The decision to confine our discussion to drug treatment research reflects the primary concern of this chapter—control of the nonmedical use of heroin. However, it should be noted that research indicating useful therapeutic applications of heroin would probably have a spillover effect on general public attitudes toward the drug.

Government-sponsored Heroin Treatment Clinics.

The "heroin treatment" envisioned by this policy could take many forms. One form would be a proposed heroin "induction" or "lure" model using heroin or injectable morphine to entice otherwise reluctant heroin users voluntarily into treatment, essentially a short-term detoxification program using heroin in the initial state and methadone in the intermediate one.3 This model, in fact, is similar to the original Dole-Nyswander research program with methadone maintenance; in that study, morphine was administered to patients who at admission showed signs of withdrawal. Substitution of methadone (administered orally) would quickly follow that initial stage, as is generally contemplated with the "heroin-lure" model of heroin treatment. However, abstinence from all opiate use within a relatively short, one-to-two-year period is often stated as the goal of the "lure" or "induction" model, whereas the Dole-Nyswander approach contemplated indefinite maintenance on oral methadone.

Another possible form for American heroin treatment is provided by the British. The current American approach to heroin treatment differs significantly from prevailing British drug treatment practice, which allows indefinite opiate maintenance—intravenous heroin, intravenous methadone, oral methadone, or any combination of methods—for opiate drug dependents.' In the United States, while the new proposed federal regulations on oral methadone treatment do not require programs to drop patients within any definite period of time, they do, however, continue to emphasize strongly the patients' withdrawal from methadone and achievement of a completely drug-free state.5 In England the choice of both the opiate and the method of administration is left to the discretion of the clinic physician; although abstinence is stated to be desirable, the British consider stabilization and normalization of an addict's life and keeping track of as many addicts as possible to be equally desirable goals. Therefore, if stabilization or continued treatment-involvement can be attained only by the continuing prescription of an opiate at stable dosage levels, then such maintenance meets the social policy objectives of British treatment.

A wide degree of flexibility marks the British response to the treatment of heroin dependency. In discussing the potential effects of a heroin treatment clinic policy in the United States, we include this characteristic in our policy model. Rather than one specific type of treatment model, the clinic policy examined could encompass a variety, whether "lure," induction, true maintenance, or other types. Attention will be called to potential differences among various models in the following discussion of the issues affecting heroin policy.

Prescription of Heroin by Private Physician.

This option is still further removed from total prohibition and total government control of heroin. Practicing physicians—rather than special-purpose, government-sponsored clinics—would be the primary dispensers of licit heroin. However, this could still permit tight controls over heroin's legal availability, in that both recipient and prescribing physician would be subject to registration, reporting requirements, and official surveillance. The strictness of these controls could vary. Prescription could be limited either to legally or medically defined addicts or to those with a legitimate medical need for heroin other than for drug abuse, such as for relief of the severe pain associated with certain cancer conditions. Distribution and administration could be handled either directly in the prescribing doctor's office or by the British practice of filling the prescription through general pharmaceutical outlets and self-administration of the drug.

For this to take effect, heroin would have to be rescheduled from Schedule I to a lower control schedule of the federal Controlled Substances Act and to lower state schedules as well (for those states that have adopted a form of the Uniform Controlled Substances Act). This rescheduling process would also have to occur in order to implement medical and treatment research and the over-the-counter drug and pure food and drug models which are discussed below.

A variant "option within an option" would be to allow physicians to exercise professional discretion in determining whom to treat with heroin, how long treatment should be continued, and what amounts of heroin are required. Such a model is analogous to the British pre-maintenance clinic "system" (i.e., pre-1968 practices) and is subject to the same risks namely, the abuse of discretion or outright drug-prescription profiteering by a few physicians. (The British experience with heroin regulation is discussed in greater detail on pages 216-219.) Government supervision would be minimal, similar to present FDA and DEA monitoring of Schedule III prescription drugs, where some reporting and recordkeeping is required and prescription refills are limited.

Removal of Criminal Penalties for Personal Possession.

This policy model could be referred to as heroin "decriminalization" or "legalization." However, those terms are at best ambiguous and imprecise. The heroin treatment clinic policy previously described is, of course, a form of heroin decriminalization, since it would permit heroin to be used and possessed legally under certain circumstances. The fact that such different schemes could be termed heroin "decriminalization" is reason enough to avoid use of that term.

The marijuana decriminalization legislation of recent years has largely consisted in the removal of the possibility of a jail sentence for first-time possession of a small amount of marijuana, generally an ounce or less. In most states adopting such legislation, the offense is a civil rather than criminal one, and the offender pays a fine (generally in the $20-200 range) as if for a traffic violation. This policy model anticipates a similar, though not necessarily identical, legislative scheme for heroin. Our discussion of this option will be predicated on a policy which eliminates all criminal penalties for possession of a small amount of heroin for personal use. It, like the new policy for marijuana, does not contemplate a legal, regulated source of supply, but merely changes the penalty for illicit possession.

Removal of criminal penalties for heroin possession could be implemented at various jurisdictional levels. For example, Congress has not changed the federal law pertaining to simple possession of marijuana; possession continues to be a federal criminal offense punishable by a prison term of up to one year. However, since 1973 several states have enacted legislation making marijuana possession a civil offense—the equivalent of a traffic violation—within their borders. Although the marijuana user remains subject to both federal and state laws, since little federal enforcement effort is directed against simple possession offenses the state law has a greater impact on users. Similarly, in states that permit "local option" ordinances, some cities have formally adopted a civil-fine procedure for marijuana offenses that differs from the otherwise applicable state law. The same pattern of piecemeal implementation of the removal of possession penalties could occur with this heroin policy model.

Over-the-Counter Drug Regulation.

Dispensing heroin without a prescription would require changes in both the federal Food and Drug Act and the Controlled Substances Act. States could not implement this policy on their own in the face of a continuing federal prohibition of heroin. Currently, the only controlled substances afforded over-the-counter regulation are those listed in Schedule V of the Controlled Substances Act. It is likely that the recipient of heroin regulated according to this policy would have to meet a minimum age requirement, offer some form of identification, and have his name entered on a record kept by the pharmacist.

In addition to the registration and minimum-age requirements, heroin sold in this manner would have to be subject to standards of purity, safety, and effectiveness set by the Food and Drug Administration. (This, however, would also be true of heroin dispensed in treatment clinics, by a physician's prescription, or in the pure food and drug model discussed below.) The Federal Trade Commission could set rules on labeling requirements and warnings as well as establish any advertising restrictions desired. Basically, this model places the decision to use heroin directly with the consumer and regulates closely only those who manufacture or distribute the drug.

Pure Food and Drug Model.

This model would allow heroin to be marketed and consumed in the United States rather as caffeine presently is in coffee, tea, soft drinks, and candy. Obviously, significant statutory changes would be required at all levels of government to change heroin from a contraband substance to a legitimate product. Formal government involvement would be limited to the regulation of the quality and purity of the heroin offered for sale. Any retail establishment permitted to sell food, drugs, or other consumables would be able to market heroin. Advertising might be limited, however, in ways similar to present restrictions on the advertisement of alcoholic beverages and tobacco products in certain media.

This policy model could also be varied so that either the federal government or the states could be in direct control of manufacture and distribution. As with state lotteries, a governmental agency could have monopolistic control over the production and sale of heroin; in that case revenues realized from sales would devolve directly to the government producer. Alternatively, private production might be allowed but with sale to consumers done only by "state stores," as is currently required for alcoholic beverages in several states.

The policy models discussed above provide an idea of the variety of ways in which we control certain psychoactive substances in the United States, ways in which heroin could also be controlled. Of these policy options four have been selected for a detailed examination of their probable effects. These four—medical and treatment research, government-sponsored heroin clinics, removal of criminal penalties, and over-the-counter drug regulation—represent a diverse yet feasible sampling of points along the overall spectrum of policy choices. Research with heroin in treatment and "heroin maintenance" clinics frequently crops up as a topic in public discussions of drug abuse. Likewise, the removal of criminal possession penalties is frequently mentioned as a possible solution to present illicit drug control problems. All of these options, however, are important only insofar as they provide an analytical framework for dealing with specific concerns regarding heroin and appropriate public policy. The following discussion deals with the major issues influencing heroin policy.

The Issues

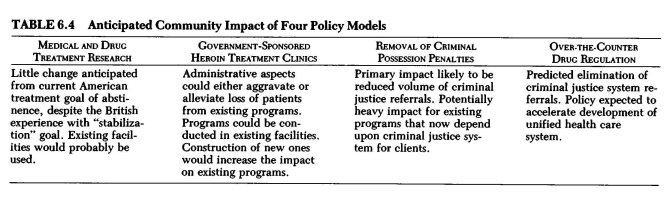

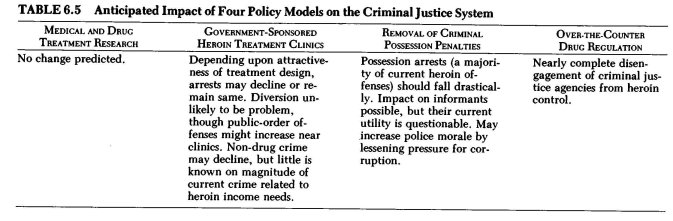

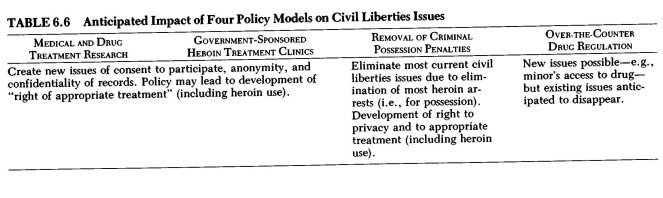

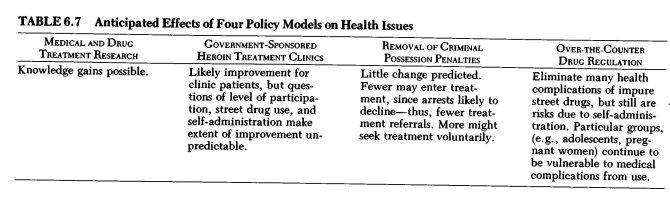

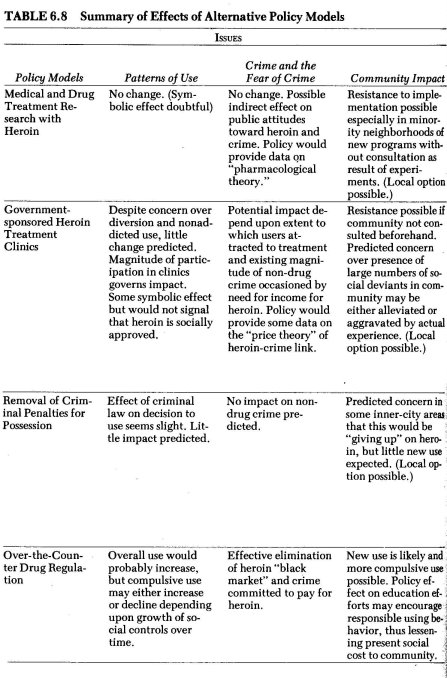

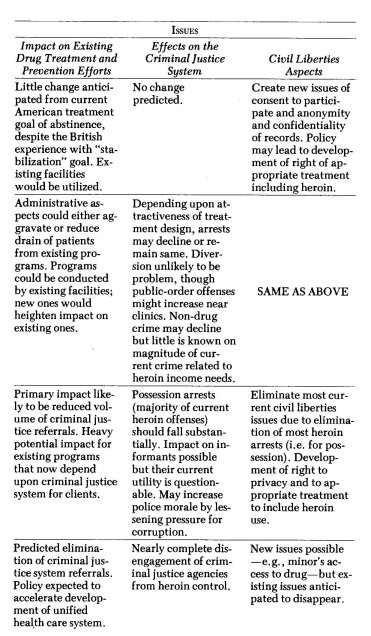

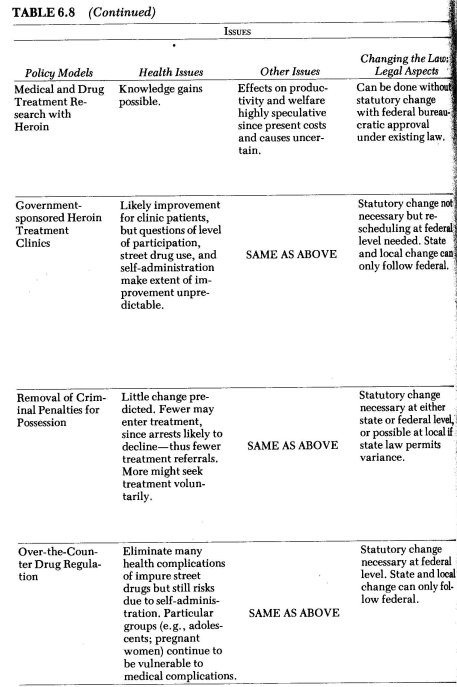

The importance ascribed to a particular issue will vary from person to person. It will also vary according to specific policy attributes. The aim of this chapter is to provide a basis for comparing the effects of different policy variables on several major areas of concern. In this way we can begin to identify those policy variables which hold special promise. An outline chart has been included (Table 6.8, pp. 244-246) to permit a summary overview of the four policy options and their predicted impact. In addition, other tables (6.1-6.7) summarize the anticipated impact of the four policy options on each specific issue.

The section below entitled "Patterns of Use" reviews the historical experiences with the fluctuating availability of other psychoactive substances as well as recent research into the extent and type of heroin use in the United States. Compulsive or dependent heroin use is a matter of particular concern in this discussion.

"Crime and the Fear of Crime" as related to heroin use is a frequently discussed topic, yet surprisingly little factual information is available on the true nature or extent of the heroin-crime link. Public attitudes and perceptions of this issue have had and will have great influence on the selection of any policy response; they are given special attention in this section.

"Community Impact" takes into account the differing impact that heroin has within the various regions, communities, and ethnic populations of the United States. Minority populations and inner-city neighborhoods are disproportionately affected by heroin at present, and are therefore emphasized in this discussion.

"Impact on Existing Drug Treatment and Prevention Efforts" and "Effects on the Criminal Justice System" deal with the impact of alternative heroin policies on these institutions, an impact depending primarily on their goals and practices. Specific policy issues such as the effect of criminal justice referrals on treatment are equally important in alternative, as well as present, policy responses.

The remaining sections deal with civil liberties, health, worker-productivity, and welfare issues. While civil liberties and health issues are matters of concern under current policy, the effect of alternatives can by no means be expected to be uniform: One policy option may create new problems to replace present ones, and another may eliminate some concerns but not others. In short, the following discussion points to no policy panacea. However, as the previous chapters herein indicate, present heroin policy is fraught with substantial shortcomings, questionable assumptions, and few identifiable benefits. The task of the policymaker is to begin to identify issues of real—as opposed to imagined—significance and reduce the costs of American heroin policy.

Patterns of Use.

The general assumption about heroin use has been that criminal penalties for possession, use, and trafficking activities deter many would-be users and keep supply at the lowest possible level by maintaining legal pressure on traffickers and consumers. Thus the conventional wisdom on proposed changes in heroin policy has been that any reduction in this pressure would result in a substantial increase in total use—and consequently in dependent use. Despite the general acceptance of these conventional theories, they have not been proven. In fact, substantial data exist on both heroin and other psychoactive substances that lead to far different conclusions.

When exploring the relationship of heroin's availability to its use, it is important to realize that there are wide variations in use patterns among those who use the drug.6 The National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse identified five primary patterns of use: experimental, recreational, circumstantial, intensified, and compulsive.' The latter two types of using-behavior constitute patterns most commonly considered misuse of drugs. The greatest policy concern, therefore, ought to be to minimize these intensified or compulsive use patterns.

In order to determine whether compulsive heroin use is likely to increase as a result of any specific policy decision we will need information on several other related issues. We need to ask whether a given policy change would increase the drug's availability; we need to know whether increased availability is likely to lead to increased use of all types; and we need to know about the relationship of compulsive use to total use. To help answer these questions we must look to data on the spread of use of both heroin and other psychoactive substances.

One potential source of data is the American experience with alcohol prohibition from 1917 to 1933, which provides some information on the effects of varying control measures on excessive consumption. However, these data are not uniform. For instance, while an old Bureau of Prohibition study showed a decrease in per capita alcohol consumption, the Department of Commerce found the opposite to be true.8 Other indicators of excessive alcohol use during the period—alcoholism deaths, alcoholic psychosis incidents, arrests for public intoxication—are equally inconclusive.9

Another possible source of information is the "gin mania," a dramatic shift from beer drinking to gin consumption that the English experienced during the period 1700-50. While the figures on taxed gin consumption suggest a tenfold increase in per capita alcohol consumption, very little is known about the causes of the "mania" or its effect, other than to say that heavy use (drunkenness) did increase as the more potent gin gained popularity relative to beer.''

The more recent use of cigarettes in the United States provides another example of how compulsive use of a psychoactive drug (nicotine) can develop after use is already widespread. Although tobacco had been used in various forms in the United States since 1613, its use did not really expand until the invention of the automatic cigarette-making machine in the late nineteenth century. However, the most significant factor in the growth of cigarette use in this country appears to have been not this new invention but rather the relentless, competitive advertising among manufacturers during the period 1918-50." Heavy advertising by commercial interests now seems to be a key factor in the rapidly escalating cigarette consumption in "third-world" nations.12 The American experience with cigarette use also indicates that a particular form of a psychoactive drug can spread at the expense of other forms, and that increasing availability, as expressed by declining price, is not necessary for rapid growth.

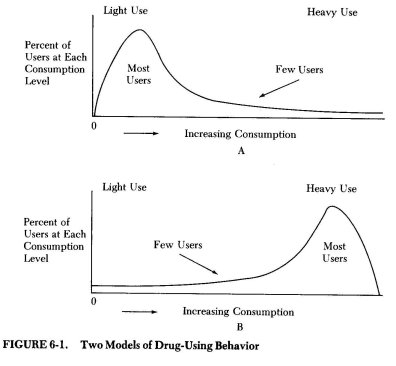

These historical examples of substance control and spread provide conflicting answers on whether compulsive use is roughly constant regardless of the number of users, or whether it fluctuates in response to increased consumption.13 The normal distribution of using behavior for most psychoactive substances (alcohol, for example) is assumed to be that represented by Figure 6.1A. According to conventional views, heroin use is distributed as shown in Figure 6.1B. However, recent studies of heroin use indicate that it is really closer to the normal curve (Figure 6.1A) than an atypical pattern of its own (Figure 6.1B). These recent studies postulate the existence of from two to four million nonaddicted users." Previous information on heroin use has tended to focus on discussions of "addicts," failing to acknowledge that heroin, like other psychoactive substances, can be used in a wide variety of patterns.

The measurement of total consumption of all types of psychotropic drugs in "normal" (i.e., non-treatment sample) populations of users shows a distribution of using behavior like that of Figure 6.1A. Since these drugs include not only heroin but also marijuana, pharmaceutical stimulants and depressants, and alcohol, it would appear that availability alone is not a controlling factor in the shape of the consumption distribution. Roughly speaking, if a drug is easy to get more people will tend to use it, but only a relatively few will be heavy consumers. If the same drug is hard to get it will tend to have fewer total users, but about the same proportion of heavy users. This argument cannot be pursued very far, of course, since we know little about the exact nature of the distributions in Figures 6.1A and B. Conceivably, the shape of the consumption- distribution curve may change somewhat as supply increases, but there is no evidence to suggest that a normal distribution curve would turn into its obverse in response to increasing supply.

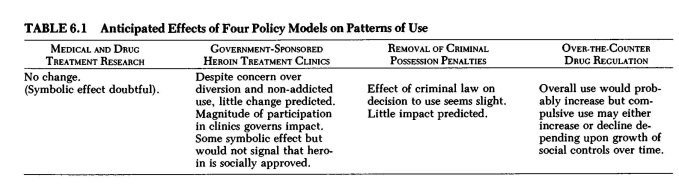

It is far from certain, however, that any movement away from current policies will have the effect of increasing supply. Looking at the following specific policy models will help us to see how the availability of heroin and the behavior of users and nonusers would be affected, if at all, by the kinds of policy adjustments considered. Table 6.1 summarizes the anticipated effects.

Medical and Drug Treatment Research with Heroin. With this very limited change in policy no great impact on current patterns of use would be likely. The very nature of this option is to permit the use of heroin only by small research populations in strictly clinical settings. However, some people have expressed concern over permitting even this very limited use of heroin, on the grounds that it would lessen the strong societal disapproval that now exists. '5 Any lessening of the rigidity of official policy would, according to this view, lead inexorably to increased nonmedical use of the drug. The use of heroin as part of an experimental drug abuse treatment plan, however, hardly constitutes a major change in official policies or social attitudes toward its use. An experimental program of any type is unlikely to affect continued societal disapproval of nonmedical heroin use—unless opponents of such a change convince the public otherwise.

Government-Sponsored Heroin Treatment Clinics. Critics opposed to the experimental use of heroin would probably be equally opposed to the broad implementation of a program of treatment clinics using heroin. Objections would almost certainly be raised, in spite of the fact that abstinence would be the most likely treatment goal of heroin treatment clinics in an American context.

Once again, however, it is doubtful that a symbolic message that heroin can be used legitimately in the context of addiction treatment would have much of an effect on general use. Permitting heroin to be given to addicted users in abstinence-oriented treatment would be unlikely to reduce the revulsion commonly felt for drug addiction by the mainstream of American society. It is likely that those inclined to use heroin—recent estimates say from 2 to 4 million persons use it in a variety of using styles—already do so in the face of strong antiheroin symbolism and actions. The symbolism of this new policy message is unlikely to affect either the numbers of users or the patterns of use any more effectively than do current efforts.

More serious are the objections to heroin treatment clinics based on potential problems of diversion and nonaddicted users, or even nonusers, being mistakenly admitted to the clinics.10 The evidence from both American and British opiate maintenance programs indicate that these problems are manageable. In the rapid expansion of American methadone treatment capacity in the early 1970s, some law enforcement officials noted appreciable illicit diversion." However, it is now generally true that methadone diversion is relatively insignificant—few if any persons have become addicted to the drug who were not already addicted to heroin.12 Assuming that the security systems adopted in an American herein treatment clinic would be at least as stringent as those in present methadone programs, it is unlikely that heroin diverted from licit supplies would be a significant problem. Likewise, admission of nonusers does seem not to be an insurmountable problem.

Additional insight into these issues can be gained from the United States' brief experience with morphine and heroin maintenance clinics.19 Opened around 1918 but closed by federal government action by 1922, the clinics—forty-four total around the country—provide valuable if disputed information on the efficacy of opiate maintenance20 Although some problems definitely did occur and, in the case of the New York City clinic, were heavily reported in the popular press, most of the clinics appear to have been operated efficiently and effectively.21 The closings were motivated more by a desire to see a reduction in the number of opiate addicts than by any proved failure of the clinics to contain the level of addictive drug use or aid in the social stabilization of clinic patients. Diversion of clinically supplied drugs and the administration of drugs to nonaddicted clientele do not, according to historical studies, appear to have been significant problems in practice. With illicit opiates still widely available on the street, there seemed to be little pressure to divert legal drugs.

A review of the British experience with clinic dispensation of heroin also gives credence to the view that drug diversion is not likely to be overly significant, nor is the possibility of nonaddicted users being drawn into the clinic. Factors other than the clinics themselves figure into the British heroin situation, but it appears that the clinics have contributed to a low-keyed societal response which has helped keep the heroin dependency at a fairly low level. The prevailing British view of their clinic system is one of "containment," rather than "maintenance," of opiate addiction.22 In fact, very little heroin is currently dispensed, although clinic physicians have the discretion to prescribe it for treatment clients. The clinic system has received steady support in its effort to limit nonmedical opiate use to those already addicted and avoid creating an environment for the growth of a large, entrenched illicit heroin distribution system. Despite the presence of illicit heroin in England, the "black market" appears not to be currently large, nor is it predicted likely to grow.23

Adolescent heroin use is also a matter for concern. The clinic option would not necessarily exclude nor include adolescent users from treatment. The legitimate receipt of heroin by youthful clinic patients would predictably be even more explosive politically than the admission of youthful users into traditional methadone programs. Whether the perceived advantages of providing treatment attractive to the youthful user outweigh the perceived disadvantages is a matter requiring more detailed examination and the exercise of careful judgment.

Removal of Criminal Penalties for Personal Possession. Implementation of this option would lead many to expect a dramatic increase in heroin use, an attitude that stems largely from our traditional reliance on law enforcement measures to control it. Many people believe that the only way to regulate drugs is to prohibit their use, enforcing that prohibition with criminal sanctions. However, drug policy seems to have less influence than is commonly presumed on personal decisions whether to use particular drugs. For example, an exhaustive study of the effects of the 1973 "get-tough" drug law in New York State showed that this strict law, even in areas where it was fully implemented by the court system and backed by law enforcement agencies, failed to demonstrate a discernible influence on the level of heroin use.24 Similarly, annual surveys conducted in the state of Oregon reveal that use patterns have changed little following the substitution of civil for criminal penalties for simple possession of small amounts of marijuana.25

The other chapters of this report have emphasized that the decades of efforts to apprehend, jail, or treat heroin users and interdict and destroy supplies of the drug appear to have had little more than transient effects on use patterns. The criminal law seems particularly ineffective in influencing the behavior of the compulsive heroin user, who is not as prone to consider the risks involved in continued use as those less involved with drug consumption. Thus, merely changing the criminal penalty structure for personal possession seems unlikely to in itself affect personal decisions whether to use heroin.

Over-the-Counter Drug Regulation. This option would make heroin far more accessible to far greater numbers than would any other. Yet one cannot conclude with any certainty that compulsive use would necessarily increase, even though it seems reasonable to predict that both general use and dependent (compulsive and intensified) use would increase to some extent. We do not know if destructive behavior would continue at the present or an increased rate; perhaps changes would also have to occur in institutional structures to promote more controlled using behavior in place of destructive patterns.

However, even though in all likelihood availability would increase, that does not seem to be the only important factor in the normal distribution curve for psychoactive drug using behavior. (See Figure 6.1 and discussion, pp. 198-200. For example, the previous discussion pointed out the role of advertising in increasing heavy, compulsive use of cigarettes in the United States and elsewhere. Heroin, contrary to sixty-year-old beliefs, appears to have developed, or is developing, a normal distribution curve similar to alcohol and marijuana use patterns.

If this is correct, one would anticipate compulsive use to continue to represent a small fraction of overall use. Nonetheless, that compulsive use would probably remain relatively small in comparison to overall use does not diminish our concern over the possibility of a net increase in compulsive or adolescent heroin use. Additionally, in light of the present widespread anxiety over any type of heroin use, any increase in general use would be of concern to most Americans. Still, current patterns of enforcement seem to be a key factor in inhibiting t íe denment oTiTóréwidely followed cntr'o o using beTiay. oi.2wWhile here is evidence of a substantial nu`~mof controlled users of heroin,27 social controls on heroin use are probably not sufficiently advanced to prevent some increase in dysfunctional use were OTC regulation to be substituted for the current prohibition approach without other intermediate policy steps.

Crime and the Fear of Crime.

Crime is perhaps the single most important consideration in both past and present heroin policy. Were it not for the assumed close connection between heroin and crime, new use—even compulsive use—would not be as great a public concern. Yet there is remarkably little information on the relationship of heroin to crime; however, that lack of knowledge has not undercut the widespread belief that there is a proved link between heroin use and consequent criminality.2B Heroin addicts are still presumed to support at least 60 percent of their heroin purchases through theft and robbery, for an estimated $695 million annual bill.29 The prediction of this annual loss is given as justification for continued, even increased, law enforcement spending on programs aimed at eliminating heroin use.

The American attitude towards heroin is deeply rooted in the history of our drug laws.30 Suppression of "narcotics"—an early catch-all word which encompassed opium, heroin, morphine, cocaine, and marijuana—proved to be popular politically. Fears of minority and immigrant groups went hand-in-hand with the fear that revolutionaries were seeking to undermine American society through drugs. For example, the Mayor of New York City established a Committee on Public Safety in 1919 to investigate "the heroin epidemic among youth and the bombings by revolutionaries."3' Such fears repeatedly surface in the development of American drug control laws;32 they were joined in the late 1960s by the idea that heroin was largely responsible for the rapidly rising rates of street crime.33

The proposition that heroin and crime are interrelated can be broken down into three more manageable concepts. The first is the "pharmacological theory," which holds that the pharmacological properties of the drug cause users to commit a variety of criminal acts, including both violent and property crimes. This view is similar to the prevailing legal view of insanity that a person can be compelled by an "irresistible impulse" to do wrong. Although this relationship is frequently assumed to exist, exhaustive studies of heroin and its pharmacological effects have not shown it.34

The second is the "social theory," which holds that because the law defines heroin use as illegal, the user will tend to be a criminal. By definition, possession or use of heroin constitutes a crime; therefore, by definition the user is a criminal. Similarly, heroin distribution activities are criminal because the law so states. The point that it is the law which ordains who is a criminal is often overlooked in discussions on drug policy. Because the heroin user is a "criminal," it is easier for the public to assume that he or she will commit other, unspecified criminal acts.

The third is the "price theory," which holds that users commit crimes such as theft, robbery, or property crimes to support their habits. The concern over acquisitive crimes purportedly committed to support use is at the heart of recent government and public concern with increasing heroin use.

The commonly held views of heroin use and crime contribute to the general belief that property crime is a necessary concomitant of use. Thus, the ordinary citizen is led to believe that the drug itself overbears the will of the user—by definition already a criminal—and causes him to commit crimes of theft or violence in order to obtain his drug. It is on this theory of a heroin-crime relationship that our discussion will focus.

There is no doubt that some, perhaps many, heroin users commit property crimes. Undoubtedly, heroin is an expensive drug which for many can only be obtained by additional, often illegal, income. However, compulsive heroin users often have a criminal history predating their heroin use,35 and it is possible that "persons who are very successful in income-generating crime may spend a sizeable portion of their income on a luxury good—heroin."38

Recent evaluations of treatment programs for heroin users show only marginal effects on reducing crime rates for enrolled patients.37 This finding supports the view that heroin use—even compulsive, daily use—is frequently an aggravating factor in property crime but is often not the primary cause. However, the conventional response is that for the criminal who uses heroin the primary cause of crime is the heroin; cessation of use is commonly equated with the "solution" of the crime problem.

Similarly, a study on the relationship between heroin price and non-drug crime rates in a large urban area (Detroit, Michigan) indicated that temporary reductions in heroin availability led to marginally higher crime rates (higher in poorer neighborhoods than in wealthier sections). 38

While these studies do have many limitations, they do seem to indicate that, to the extent that a relationship between heroin use and property crime exists, it exists because of the high cost of heroin. Thus, to the extent that drug policies increase the cost of heroin, property crimes can be expected to increase in areas where compulsive use is high and income levels low. If it is true that an increase in heroin price may lead to increased crime, it is probably also correct to predict that lower heroin prices may lead to some decline in crime rates.

It is difficult, however, to say much at all about crime rates. Reported crimes are but a fraction of actual crime, and crimes resulting in an investigation or arrest are an even smaller fraction. Increases or declines in the number of those arrested for non-drug offenses who are also heroin users mean little if their relationship to total crime is unknown. For example, the recent report on the effects of New York's so-called "Rockefeller drug law" found that in New York City during a period of rapidly increasing crime the percentage of narcotics users among those arrested for non-drug felonies declined (from 52 percent in 1971 to 28 percent in 1975)." Data such as these still give an incomplete picture, since we do not know the relative proportion of reported crime to actual crime or, in fact, of heroin users to nonusers for either reported or actual crime.

While the true nature of the heroin and crime relationship may eventually be better understood, at the moment how the public perceives that link is of paramount importance. The development of our antinarcotics laws reflects a history of shifting fears about certain proscribed drugs and their users. Apart from whatever the danger actually was, these fears motivated public support and prompted policymakers' support of stringent law enforcement policies. Fear of crime, much more than actual crime, underlies our current response to heroin.

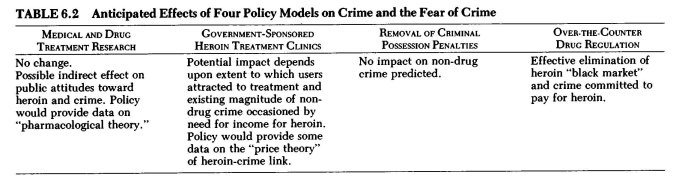

Table 6.2 summarizes the anticipated effects of the four selected policy models—research, clinics, removal of penalties, and over-the-counter drug regulation—on non-drug crime and public perceptions of the victimization risk.

Medical and Drug Treatment Research with Heroin. Implementation of this policy option would offer the possibility of developing substantial empirical data on the pharmacological effects of heroin on compulsive users. Such information might help to put to rest the notion that the effects of the drug cause users to commit crimes.

Permitting scientific research with heroin in a treatment setting would not in itself alter our current prohibition on the use of the drug outside of that small experiment. Greater public understanding about heroin and its effects would affect public attitudes toward those using the drug. For example, wide public recognition that the high cost of heroin, rather than its pharmacological properties, leads to the revenue-producing crimes some users commit would have important public-policy ramifications.

It is also possible, however, that the experimental programs may indirectly harden public attitudes toward heroin and crime. For instance, any incident involving a participant of an experimental program in a criminal act may be viewed as substantiating a firm heroin-crime link. We are all familiar with news reports headlining a person's past involvement with a mental health institution, no matter how incidental that contact is in relation to other aspects of the person's life or the incident being reported. Likewise, the tenacity of the myths and misconceptions about heroin cannot be overestimated.

Government-sponsored Heroin Treatment Clinics. For heroin treatment clinics of any type to become a reality, there must almost certainly be a strong belief in their crime-reduction potential. Substantial doubts about clinics' ability to reduce crime would leave humanitarian concern for the addicted heroin user as the chief reason for the approach, and such concern for the user's welfare really has not been a primary element in past heroin control policies; it seems unlikely to emerge as a critical consideration at this juncture. Even given an initial atmosphere of support, the public mood could shift rapidly if there were adverse publicity of clinic problems (such as occurred with morphine and heroin maintenance clinics in the period 1918-2240) or a lack of noticeable results in crime reduction (especially if there were a "hard-sell" public relations campaign on that issue). Because public fears about crime are based so much on perceptions, rather than actual levels of crime, the effect of heroin clinics would depend upon these intangibles and could only be assessed accurately in retrospect.

Nonetheless, studies of drug treatment reveal that criminal activity generally declines to some undetermined degree (although not completely) while a person is enrolled in treatment. '41 The real difficulty is in determining the magnitude of this reduction and which influences are responsible for it. If the addition of heroin to a treatment program—whether it be "maintenance," "lure," or some other concept—would at- ' tract a substantial portion of the large population of compulsive users who have never been in treatment, it may be possible for these clinics to have a measurable impact on non-drug crime. Even if they did not attract significant numbers of clients, they might, as current programs do, help reduce the total amount of crime. To the extent that crimes are committed to secure funds to pay for high-priced illicit heroin, enrolled clinic patients would have one less need for income.

Removal of Criminal Penalties for Personal Possession. This option would lead us to expect no change in the market prices of heroin; the mere removal of penalties for possession of small amounts would not create a legal supply of heroin nor would it effectively reduce the profitability of illicit heroin sales. Thus, one could expect whatever crime is being committed to pay the street price of heroin to continue whether possession were punishable or not.

Over-the-Counter Drug Regulation. More than the other three options, this policy could only come about after significant changes in public attitudes toward heroin and crime had occurred, rather than be a factor in changing those attitudes. Putting aside the question whether this option would have a realistic chance of being implemented, the potential impact of over-the-counter regulation on non-drug crime would be enormous. As noted previously, heroin's high street price is undeniably a factor in the resorting to theft and other illegal sources of income by some users. Should heroin become as cheap as aspirin or Valium, it seems logical that the need to resort to theft to pay for even a heavy heroin habit would be effectively eliminated."

Community Impact. It is clear that the effects of heroin policy are felt most acutely at the local community, neighborhood level. Some neighborhoods are much more affected than others by heroin users and governmental heroin policy. There is therefore an obvious danger in talking about the effects of alternative policies on the "community" as if there were a common reference point. Certain aspects of heroin policies will have disproportionate effects on specific communities within larger metropolitan areas.

Compulsive heroin use tends to cut the user off from the society of nonusers and enmesh him deeply in that of other deviants. This "disenfranchising" effect is the most notable community impact of heroin use at present. Laws making use a criminal act stigmatize the user, as does the association of revenue-raising crimes with heroin use.

The communities most affected by heroin are those most affected by a deeply rooted set of social maladies—poverty, unemployment, racial prejudice, inadequate housing and transportation, poor education, and poor vocational training opportunities. These communities experience heroin dependence and trafficking as additional hardships.

Permitting a degree of "local option" among policy alternatives may help to minimize potential negative consequences and increase the opportunities for community improvement. Many localities—entire states, even—today have little problem with heroin use and associated social problems; for these areas it may be logical to continue a prohibitionary approach. For other areas, where the use of illicit drugs is high despite efforts to prevent it, it might be more appropriate to allow greater local discretion in the formulation of drug policies and programs. To some extent, local option occurs even under present policies; for example, some metropolitan police departments choose to ignore heroin possession offenses, and some courts establish informal penalty structures for them.

There are many precedents for "local option" in the regulation of substances or activities. Alcohol consumption regulation, for example, has been left largely to the individual states. The federal government regulates only international aspects, production, interstate transportation, and unfair practices regarding alcohol." States have come up with a considerable variety of regulatory control schemes; the majority of them also provide some form of "local option" for municipalities, counties, or other organs of local government.

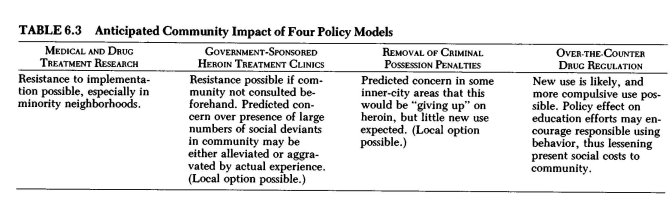

Other examples exist as well. Gambling is now primarily a subject for state or local, rather than federal, control." Laetrile, a compound derived from apricots and claimed by some to be a cancer cure, is at present only regulated by the states (though the federal government may intervene in the future). Likewise, as discussed previously, some degree of "local option" has emerged with marijuana regulation; differences among the states and the federal government on marijuana, however, have been confined to the severity of the penalty for possession. Table 6.3 summarizes the predicted impact of particular heroin policy options at the neighborhood level and indicates where "local option" may be feasible.

Medical and Drug Treatment Research with Heroin. Implicit in this option is a very limited scale of closely monitored experiments. Experimental research with heroin under these circumstances would not be likely to have much immediate impact on the community, local or otherwise. For example, the use of heroin as an analgesic for cancer patients would occur within established hospitals; no new facilities would have to be created nor additional patients sought. Similarly, the use of heroin in experimental drug treatment therapy would most likely be undertaken in existing medical research centers, hospitals, or drug treatment programs, carefully selected for program quality and security.

There is, however, great concern expressed by some community spokesmen that experimental heroin treatment research would lead to the rapid expansion and permanent establishment of "heroin maintenance" clinics. Those in minority communities often suspect that their desires and needs on the local level will be ignored by federal policy makers, and, just as the initial success of Drs. Vincent Dole and Marie Nyswander with methadone maintenance led to large-scale federal support for methadone clinics, so the fear is that, regardless of community feelings, experiments with heroin in drug treatment will inevitably lead to a national heroin clinic system with most centers located in inner-city areas.

Although this apprehension persists, many local leaders seem convinced of the need for heroin treatment research. The National League of Cities (NLC), as part of its 1977 National Municipal Policy Statement, passed a resolution which supported further study of heroin maintenance, including specific research studies with heroin. Reaffirmed in 1978, this action by the NLC is an indication that experimental research may indeed be not just possible but actually welcome in certain communities. Local officials and their constituents express concern over the continuing high social costs of compulsive heroin use under present policies, and seem more willing now to consider and examine alternatives previously regarded as too radical or controversial.

Medical heroin research could have a widespread educational effect, and could help break down many of the present misconceptions about the drug. Public acknowledgment that heroin is a drug with a capacity for both beneficial and adverse effects, depending upon the circumstances of its use, would be a significant advance in public understanding regarding the drug. Research studies may help to produce this public understanding.

Government-sponsored Heroin Treatment Clinics. Resistance to the location of drug treatment facilities in residential neighborhoods has frustrated the desire of many drug treatment programs to be close to the population to be served. While in the abstract everyone is eager to have community-based drug treatment, a caveat is that the proposed facility should be on someone else's block, near someone else's home, family, and neighbors. Heroin treatment clinics would face even greater hurdles of public resistance than other, existing forms of drug abuse treatment in the United States. The treatment in using heroin to stem compulsive use will have to be fully and carefully explained. In spite of explanations of the treatment process, there may still be objections to the clinics because of the fear of new crime they may engender.

To the extent that clinically supplied heroin would reduce a user's need for illegal income to pay for street heroin, the community would be better off. However, users who support their use through crime tend to rely on criminal activities to satisfy their other income needs as well. Despite the provision of clinic heroin, crimes by some program clientele can be expected, since such behavior already occurs in existing treatment situations. However, it would be unfortunate and inaccurate for the local community to point to such crimes as evidence of the failure of the treatment programs.

Regardless of the crimes actually committed, the presence of a group of social deviants—often criminal—within a residential area is a frightening prospect to those who see themselves or their children as likely victims. If experimental treatment programs using heroin precede the institution of heroin clinics, community perceptions of the risk involved may change. A successfully run experimental research program may help ease fears of heightened criminal activity in the neighborhood of the program. Attitudes may evolve sufficiently to permit clinics to be established within neighborhoods where the problems of compulsive heroin use are most severe. However, the potential for reversal is also great, since highly publicized, negative incidents involving a program or one of its clients could conceivably affect acceptance of all such programs and lead to demands for their abolition. This scenario occurred during the early 1900s with American morphine and heroin maintenance clinics,45 and to a lesser degree with the more recent methadone clinics.

Removal of Criminal Penalties for Personal Possession. To the extent that crimes are committed to pay for heroin, this policy change would not alter the present situation. While this change would eliminate the social deviance labeling of heroin use which may contribute to users' criminal behavior, it is unlikely to alter significantly present patterns of criminal behavior.

In some black and Hispanic communities, spokesmen have charged drug law enforcement authorities with an abdication to lawlessness by failing to strictly enforce penalties against heroin use and possession. This tension between the community and the authorities is heightened by both real and perceived differences in police effort between poor and wealthier sections of our cities. A policy mandating the uniform application of decriminalization of heroin possession may help end such discriminatory law enforcement practices, or may instead stimulate renewed charges of an official surrender to widespread drug use.

The policy is also unlikely to satisfy concern over new use, especially use by the young, school-age segment of the population. While white, black, and Hispanic neighborhoods are equally concerned with spreading heroin use, it is unlikely that new use would be evenly split between predominantly white suburban areas and predominantly black or Hispanic inner-city areas. At least one study suggests that inner-city neighborhoods are already nearly saturated with heroin in that it seems to be readily available.4B However, the notion persists that removing criminal penalties would further increase availability in these inner-city neighborhoods and result in higher rates of use.47 To the contrary, easier availability would seem to have the greatest potential impact in those neighborhoods where heroin is now typically more difficult to obtain, for example, in largely white, middle-class suburban areas.

Even in these areas new use may not automatically result from mere removal of criminal penalties for possession. Studies of drug use over a ten-year period among the school population of a suburban California school district suggest that in many communities heroin is seldom used even when available.48 However, other recent studies suggest that the use of heroin is more prevalent than is commonly believed.49 Regardless, the rates in inner-city areas are conceded by all to be the highest, and are thus the least likely to be greatly affected by this policy option.

If criminal penalties for possession of heroin were to be removed, there is some evidence to support the view that many people would come to eventually favor the policy. During the four years following the decriminalization of marijuana in Oregon, surveys noted increasing support for the policy, even for more liberal extensions of it.5° However, public support of drug decriminalization does seem highly drug-specific. To suggest that such support would grow for heroin at the same rate as for marijuana would be to ignore the very real social stigma and fears in every American community surrounding heroin use, as well as the actual differences between the two drugs.

Over-the-Counter Drug Regulation. Some information on the potential impact of over-the-counter drug regulation of heroin can be obtained by examining the British experience prior to 1968. Before enacting the Dangerous Drug Act of 1967, the United Kingdom had experienced a rapid growth in the number of known heroin addicts, from 342 in 1964 to 2,240 in 1968.5' This growth, while minimal compared to the estimated population of American addicts, alarmed the British public and their lawmakers. At the time any physician could prescribe heroin or cocaine for nearly any reason, and a very small number abused this public trust by writing prescriptions on demand to increasing numbers of users. The 1967 act and, ten years later, the 1977 Misuse of Drugs Act (which required physicians to be specially licensed), were passed in response to this problem of overprescribing.

One view of this relatively unrestricted access to heroin is that sooner or later new users will come forth, and more compulsive users will result. Doubtless this situation will be feared in nearly all communities, even though relatively little problem exists with morphine and codeine which are available now in any corner pharmacy. Some experts have postulated that for many compulsive heroin users the attraction to the needle may be as great as the attraction of the drug itself.52 An over-the-counter policy for heroin, while unlikely at present, could conceivably become an appropriate regulatory vehicle for the control of dysfunctional heroin use at some time in the future.

Impact on Existing Drug Treatment and Prevention Efforts. The primary modes of American drug treatment for heroin addiction at present are methadone maintenance, detoxification using methadone or other pharmacological assistance, and various types of drug-abstinent programs such as "therapeutic communities." The quality and number of supportive services—which include employment, education, and psychiatric counseling—vary widely within these broad treatment categories.

The largest single mode of drug treatment in terms of numbers of heroin-using clients and official expenditures is methadone maintenance. Short-term detoxification programs generally operate within existing health facilities and are also numerous. Therapeutic communities, while fewer in number and smaller in size, provide an alternative for heroin users motivated to become totally abstinent.

As the federal effort to eliminate illicit drug use expanded rapidly in the early 1970s, court referral and diversion programs for illicit drug users emerged as an important new ingredient in the modern American heroin use treatment scheme. Clients are now referred to treatment as a condition of probation or parole or are "diverted" into it before trial. These referrals from the criminal justice system now comprise a significant portion of all treatment populations.53 Although the selection of treatment in lieu of continued imprisonment or criminal trial proceedings is technically voluntary, the client is faced with a difficult choice between alternate forms of official supervision and control; since at least some element of coercion is involved, he or she cannot be considered an entirely "voluntary" entrant into treatment. One would therefore expect the greatest impact of alternative policies among drug treatment clientele to be felt by this group, a highly significant and numerous segment of the total heroin treatment population. Particular types of drug treatment may be disproportionately affected, depending upon the policy alternative, as is shown in Table 6.4.

In the face of rising drug use among the young in all social and economic settings, "drug abuse education" and "prevention" became national concerns by the late 1960s. The earliest school-based education programs tended to rely more on fear than fact. Later programs were geared more toward providing factual information and avoiding value judgments. However, the underlying assumption of educators seemed to be that once the pupil had the "true facts" he or she would decide not to use illicit drugs. The goal sought by all educational programs was and still is complete abstinence from illicit drugs. (In fact, in some communities the abstinence goal is so strong that undercover police activity has been termed part of those school "drug education" efforts.)54 The reason most often given for continuing heroin prohibition is that any relaxation in official attitudes would diminish the present stigma attached to heroin use and lead to increased use.

More recently, programs have sought to reduce the use of licit psychoactive substances like alcohol and tobacco products as well as illicit drugs. However, the arbitrary and pharmacologically artificial distinctions between illicit and licit drugs place educators in a difficult position. Drug educators are caught in an inherent contradiction in telling students that licit drugs can generally be used responsibly (though they can be mis-used), but that illicit drugs must never be used. However, policies focused less on the drugs themselves might be better able to promote the concept of responsible use whatever the substance.55 Policy changes which demonstrate heroin to have the capability for both harmful and beneficial applications (i.e., use as analgesic for cancer patients) might increase the understanding of the general public about drug use and misuse. Drug education of this very broad sort is the kind that seems most needed.

Table 6.4 summarizes the predicted impact on existing drug treatment and prevention efforts discussed below.

Medical and Drug Treatment Research with Heroin / Government-sponsored Heroin Treatment Clinics. The research model envisions a trial of new treatment modalities for attracting, retaining, and treating compulsive heroin users. What is curious is that many current drug treatment and drug education workers are alarmed by discussion of experimental heroin treatment research. All recent proposals to try injectable opiates as part of an experimental heroin addiction treatment program have as their ultimate goal complete abstinence,56 as do current methadone and drug-free approaches to heroin addiction. From all appearances, the intent of proposed experimental approaches using heroin is identical that of the existing American efforts with methadone.

There are, of course, other possible program goals which do not necessarily include total abstinence from drug use. For example, a former federal drug policy spokesman has described opium maintenance in Iran, heroin maintenance in Great Britain, and methadone maintenance in the United States as identical in their predominant objectives: reduction of social costs, stabilization of the treatment patient's life, and establishment of a means of control over the patient so that a therapeutic relationship has a chance to develop between the patient and treatment personne1.57 Heroin research and treatment programs suggested for American investigation would be unlikely to differ from these goals.

Should American researchers prove—as English clinicians have done already—that heroin can be used appropriately in a treatment setting, current American treatment and education efforts may be led to reevaluate their positions on heroin. They may consequently focus less on heroin use per se and more on making the treatment client functional in society. On the other hand, present goals expressed by treatment programs—lower social costs, stabilization, and control leading to eventual abstinence—would probably remain. The important changes would be in the general philosophical consensus on how to achieve these goals.

A fear frequently expressed when "heroin maintenance" is proposed is that new clinics would be implemented as methadone maintenance clinics were only a few short years ago, raising the public's expectation of a quick and easy solution to the social problems associated with heroin use. Leaving aside for the moment objections to using pharmacological supports in the treatment process, one can see the risks in this. Although treatment professionals can point with pride to certain benefits of methadone treatment, it has been far from the quick solution to urban crime and heroin addiction overzealous advocates promised. To make unfulfillable promises in connection with heroin clinics would tend to undermine all drug treatment, despite very real accomplishments and reasonable potential. The impact on existing treatment would largely depend upon what results are predicted from the use of heroin in treatment.

Another fear is that a large-scale program using heroin for drug treatment purposes would draw clients away from existing programs. This belief seems to be based on the assumption that heroin is so intrinsically desirable that, given the choice, people would prefer to use it over any other substance. Despite solid evidence to the contrary,58 this belief in heroin's overwhelming attractiveness persists, convincing many that the use of heroin in treatment would virtually force other treatment modalities to cease operation.

There is another reason for believing that new-style heroin treatment clinics might draw clients from existing programs: the quality of treatment services provided. The high volume of criminal justice-referred clients in "drug-free" programs and the frequently criticized "gas station" approach of some methadone programs are just some of the problems of existing programs. These problems lend support to the view that voluntary clients would, if possible, leave present programs for the new clinics.

However, it would not be necessary for new programs to be completely independent of present treatment efforts. For example, some dependent individuals might not be ready to become abstinent or switch drugs (methadone), but they might be prepared to take an initial step toward controlling their heroin use by enrolling in a treatment program that supplied the drug; later they could be directed toward another treatment regimen. It is also possible that treatment efforts might not focus so intently upon achieving abstinence, but would tolerate or encourage controlled using behavior in return for personal and social stabilization.

Administrative regulations could either alleviate or exacerbate the potentially adverse impact on existing programs. For instance, if failure in other types of treatment were made a prerequisite for admission to the new clinics, it is possible that some would enroll in existing programs just to "fail" and be eligible to participate in a heroin clinic. Decisions on whether to allow "take home" drugs or require on-site administration would influence the relative attractiveness of the new heroin clinics over existing methadone programs. Also, having to visit a clinic for a heroin injection more than once a day, if required, might make heroin clinics relatively unattractive to those interested in stabilizing and normalizing their lives.

Some information can be obtained by looking at the English experience with heroin treatment. In what is commonly referred to in America as a "heroin maintenance system," English law and medical practice permit clinic doctors to prescribe injectable heroin to maintain addicted users, generally on a weekly basis; these prescriptions are filled through local pharmacies and reviewed frequently for dosage level—and for the question of the necessity of continuing to prescribe heroin. The ultimate decision of whether to prescribe heroin is left to the clinic physician. Actually, little heroin is currently prescribed; oral and injectable methadone are increasingly preferred by clinicians as maintenance drugs.59 However, heroin may still be prescribed, should the clinic physician feel it to be in the best interest of the patient.

The British situation provides evidence that methadone and heroin treatment need not be incompatible. If American treatment programs would use heroin along with or in place of methadone, this addition of heroin as a support drug in the treatment process might enhance the overall attractiveness of treatment. Drug treatment therapists stress the importance of establishing contact with the user as a first step toward controlling compulsive drug use. It is possible that heroin clinics would encourage more troubled users to seek treatment, whatever the type, rather than merely redistributing the same individuals being treated at present.

The impact of such new clinics on existing American drug treatment programs would also depend somewhat on whether new, separate facilities are required. Separate facilities for new programs would probably mean that the prospective treatment client, not the physician, would have the most control over the choice of treatment program, since current programs tend to compete for similar clientele. New facilities would require initial capital expenditures for construction, and this would either draw funds away from existing funded treatment programs or require additions to the drug abuse treatment budget. Since federal government treatment funding has been relatively stable over the last few years—reflecting both budgetary constraints and reduced interest in drugs—reallocation of existing funding is more likely than new budget additions.

However, nothing necessitates separate facilities to implement this policy. In fact, the variety of ways in which heroin could become a part of addiction treatment—e.g., use with other drugs, use only in the beginning, and so forth—suggests that its integration with existing efforts could be an eminently reasonable approach. Existing methadone programs with appropriate counseling and support services and adequate security could be adapted relatively easily to accommodate the ancillary use of heroin in treatment. And other medical delivery systems could be utilized; for example, one writer has proposed utilization of health maintenance organizations (HMOs) to provide heroin treatment."

Removal of Criminal Penalties for Personal Possession. Enactment of heroin decriminalization measures similar to current marijuana legal reforms would greatly affect the numbers of court-referred treatment clients. "Drug-free" treatment modalities would be especially affected, since most referrals at present go to them rather than to methadone programs.e1 However, should heroin decriminalization impose a requirement that the offender be referred to treatment rather than given a civil fine, more criminal justice referrals would be likely.

Aside from that possibility, indications are—despite our inability to predict precisely—that the level of treatment referrals (if treatment referrals are not mandatory) would drop. Marijuana decriminalization in California led to a dramatic drop in the number of marijuana law offenders sent to treatment or education facilities by judges who felt jail was an inappropriate or extreme punishment. Any decline in drug treatment populations is significant to the programs involved, since government funding is tied to the number of clients. If existing treatment programs were unable to enhance the quality of their present services and attract an increased number of purely voluntary entrants, treatment populations would probably decline substantially, and with that decline would come a funding reduction.

Despite removal of possession penalties for heroin, court referrals could continue to be significant to treatment programs if heroin users arrested for non-drug crimes were referred to treatment in lieu of imprisonment or trial or as a condition of probation or parole.

Implementation of decriminalization of heroin may also lead to greater acceptance of the concept of "responsible use" by drug treatment, education, and prevention professionals. No longer compelled indirectly by law to concentrate on abstinence, these professionals might begin to narrow their efforts in order to deal with truly compulsive or dysfunctional using patterns. On the other hand, the strength of the current abstinence goal of treatment programs would indicate substantial difficulty in making this conceptual change.

Over-the-Counter Drug Regulation. Over-the-counter regulation of heroin would seem to spell an absolute end to criminal justice referrals to treatment. Whatever treatment was provided would have to be done on a purely voluntary basis, except for some minor mandatory programs similar to those for intoxicated drivers (the driving-while-intoxicated [DWI] programs) that now exist in many states.

Over-the-counter regulation of heroin would tend to accelerate the trend toward a unified health care delivery system for a variety of medical, psychiatric, and social needs. The expansion of general health services to include antiaddiction, detoxification, and similar services for those with drug problems may come through existing health maintenance organizations or similar group-care programs. Alcoholism treatment programs are presently offered by a variety of medical service systems—hospitals, HMOs, individual doctors, and private self-help organizations. Over-the-counter heroin regulation would provide an impetus for these medical care providers to expand their services to include persons with other drug problems, including heroin.

In an expansion of the traditional health care delivery system to meet the special problems of the misuse of no-longer-illicit drugs large-scale separate drug treatment programs would probably cease to exist. However, the continuation of privately funded therapeutic communities and self-help, drug-free programs would be likely; it is possible that these programs would be able to reestablish their attractiveness to voluntary clients. For example, Alcoholics Anonymous is currently a widely recognized self-help program for those with alcohol problems.

Adoption of OTC regulation for heroin would almost inevitably mean that the consensus of opinion on a relationship between heroin and crime had changed. Abandonment of the crime-control aspect of drug treatment—particularly for methadone maintenance—would also be a factor in the absorption of existing treatment into a broader health and social-service provision mechanism and the consequent disappearance of separate facilities for drug treatment.

Effects on the Criminal Justice System. The phrase "criminal justice system" refers to a varied group of institutions and individuals who together enforce and administer American criminal law. There are three major subgroups: law enforcement, the courts, and corrections. Within each of these subgroups are divisions based on a specialized function and the jurisdictional authority of the government agency in question. Federal, state, and local authorities overlap and occasionally conflict in the enforcement and administration of drug laws. In order to gain a better understanding of how alternative policies may affect particular criminal justice agencies, it is important to keep in mind the complexity of the system and its interrelationships and note that policy enacted by one level of government may conflict with that of another.

Law Enforcement. Local and state police comprise the bulk of the drug law enforcement effort. However, there are several agencies at the federal level that are significant in terms of policy leadership and as a source of law enforcement funding. These agencies—primarily the Drug Enforcement Administration, the Customs Service, and the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration—have major responsibilities and interest in American heroin law enforcement. However, their policy missions are more narrowly drawn than those of the ordinary police force.