5. Marijuana and Cocaine: The Process of Change in Drug Policy

| Reports - Drug abuse council report |

Drug Abuse

5 Marijuana and Cocaine: The Process of Change in Drug Policy

Robert R. Carr and Erik J. Meyers

The authors acknowledge with gratitude the contributions of Jared R. Tinklenberg.

MARIJUANA IS ONE OF THE FEW illicit drugs with which nearly all Americans are at least somewhat familiar. Most of us have a good idea as to how the drug is consumed, and in fact the latest surveys show that a quarter of the American adult population has used marijuana at least once—a figure that indicates that if we have not used the drug ourselves we certainly have friends, relatives, business associates, or acquaintances who have.

The continuing debate over marijuana is also a matter of great familiarity. Despite the remarkable consistency of official reports on marijuana—from the 1894 Report of the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission to the 1972 report of the National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse, Marihuana: A Signal of Misunderstanding, and the 1977 HEW report to Congress, Marijuana and Health— in addressing beliefs that marijuana is addictive, leads to violent crime, and that its use results in the use of other drugs, a national debate has continued nearly unabated. Researchers have sometimes been called upon to provide evidence either of marijuana's harmfulness or of its harmlessness. Much of the public has been simply confused over the conflicting reports. The factor most often lacking in this ongoing argument over public policy has been objectively derived evidence.

Given the stridence of the opponents it is remarkable that American marijuana policy has changed at all within recent years. It is instructive to examine the process of change that has occurred. Marijuana "decriminalization" has come about within the lifetime of the readers of this report, an experience which shows that public attitudes toward a particular drug can shift significantly, leading to the abandonment of long-held beliefs and practices in favor of less socially destructive drug policies. However, the long, slow process of marijuana "decriminalization" indicates also how difficult any drug policy change is; the national experience with cocaine provides confirming evidence of this tenacity of the law enforcement approach to drug control in the United States.

We begin with a look at those who use marijuana today, at their numbers, demographic characteristics, and reasons for using the drug. Following this section, the background and process of change in the marijuana laws from harsh criminal penalties to "decriminalization" are examined. The medical and social science arguments used by both sides of the marijuana issue are reviewed in detail, and we close with an analysis of the impact of marijuana finalization in the state of Oregon.

The afterword on cocaine quickly reviews recent developments associated with that drug's rising popularity in the United States. Once again the medical and social science arguments are enumerated and briefly evaluated, as is the policy response to the drug. Finally, the American experiences with cocaine and marijuana are compared and contrasted, with particular attention paid to the policy impact of those differences and similarities.

Current Patterns of Use

Demographics of Use: Who Uses Marijuana Today?

The "typical" marijuana smoker today is practically indistinguishable from his nonusing peers. In the more distant past,f marijuana use in this country was most commonly associated with racial and ethnic subgroups and certain occupations, such as jazz musicians.`; With the recent growth of use, first on college campuses and then elsewhere, marijuana in the 1970s became no longer restricted to any particular group or class within the general population. This broadening of the social base of users has undoubtedly been an important element in the move to decriminalize possession and use of marijuana.

Marijuana use cuts across all demographic lines, with age the sharpest dividing line (though the disparity of use levels between age groups masks the fact that a large number of individuals over age twenty-five have used and continue to use marijuana). Educational attainment is also highly correlated with marijuana use: Thirty percent of college graduates and those with some college experience have used marijuana, and 50 percent of present college students have at least experimented with it, while only 12 percent of those adults who are not high school graduates and 22 percent of high school graduates with no college experience have used the drug. Similarly, professional and higher-income adults rank among the highest of all occupational groups in the experimental use of marijuana.'

I Although male users outnumber female users by two-to-one in surveys taken since 1971, recent high school student surveys indicate that this gap may be narrowing.2 Total use within minority American population groups was estimated at 25 percent in 1976, compared with 21 percent for adult whites.'

Marijuana use varies significantly among cities of varying size and among regions of the country. In the largest twenty-five metropolitan areas as well as in other metropolitan areas (SMSAs) approximately one of every four adults has at least tried marijuana, whereas in nonmetropolitan or rural areas only one in eight adults has tried it.' Regionally, the western states have the highest percentage of use. Twenty-eight percent of western adults say they have used marijuana, while in the northeastern states 24 percent report use as do 19 0percent in the north central states. The southern states, which have traditionally shown the least use, still trail other regions among adults, but use has more than tripled since 1971, from 5 to 17 percent.°

Prevalence and Incidence of Marijuana Use.

The use of marijuana, both experimental and current,* has increased significantly since 1971, although regular use seems to be leveling off. In the 1976 national survey commissioned by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), adults and youth showed similar experiences with marijuana: 21.3 percent of the adults (age eighteen and over) and 22.4 percent of young people (ages twelve to seventeen) reported having used marijuana.e Three earlier national surveys documented the upward trend in cannabis use; comparable figures for youth in both 1971 and 1972 were 14 percent, which rose to 23 percent in 1974. For adults, use went from 15 percent in 1971 to 16 percent in 1972 to 19 percent in 1974.'

urrent marijuana use (reported use in the past month) doubled for youth etween 1971 and 1974—from 6 to 12 percent—but had increased only slightly by 1976 to 12.3 percent.° Though experimentation among adults is as high as among youth, there are fewer current users in the adult group; this figure has remained at about 8 percent since 1972.',

Marijuana experience is still predominantly associated with youth and young adults. The eighteen to twenty-five-year-old segment of the adult population has had the greatest experience with the drug, with 53 percent having used it, of whom 25 percent practice current use. The figures drop for the twenty-six to thirty-four-year-old group, to a range of 36 to 11 percent, and drop still further for the thirty-five-and-older group. Among youth, total marijuana experience varies from 6 percent between the ages of twelve and thirteen to 40 percent at ages sixteen and seventeen. (Current use is 3 and 21 percent respectively for these age groups).9

An annual national survey of a random sample of thirteen thousand high school seniors on lifestyles and values relating to drugs shows a significant increase in marijuana smoking between 1975 and 1976 for this group: 47 percent in the class of '75 had used marijuana while 53 percent in the class of '76 had done so. Those who had used marijuana within the preceding month (current users) increased from 27 percent to 32 percent.10

Drug use surveys among male high school students in San Mateo County, California, have been conducted since 1968.11 These surveys provide particularly good indications of drug use trends among school-age youth. The use of marijuana in this particular area may have reached a plateau, while the use of some other drugs seems to be diminishing; marijuana use rose from a 50 percent level in 1969 to stabilize at about 61 percent in 1972, where it has been ever since. A report of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare notes that, now that California has decriminalized the personal possession of small quantities of marijuana (1975), the results from this annual survey may serve as one measure of the impact of decriminalization on adolescent use.12

The first marijuana experience for a large number of users now occurs between the ages of fourteen and twenty-one. For example, in the period 1975 to 1976, 9 percent of youths age fourteen and fifteen had tried marijuana for the first time in the previous twelve months; the corresponding figure for those sixteen and seventeen was 13 percent and for those eighteen to twenty-one, 11 percent. At present, relatively few individuals begin use after age twenty-five; incidence of first use within the past year for those age twenty-six to thirty-four is only 4 percent, and for those past thirty-five, less than .5 percent. '2

Causes of the Increase in Use.

There are probably as many reasons for using a particular drug as there are people who use it. Obviously there must be something perceived as enjoyable in the drug's effect for beginning or continuing use to occur. However, the history of marijuana use is involved with and complicated by the political and social upheavals occurring in the 1960s and early 1970s, the time of the drug's growing popularity. For many, smoking marijuana was a symbol of protest against the Vietnam War and the "establishment" in general. These were largely concerns of college and draft-age youth, but they were echoed by others both younger and older. As use became more endemic, the teenager or young adult who had never tried marijuana was quite often in the minority within his or her subgroup; peer pressure may have played a part in getting many to experiment with the drug.

Unquestionably, during the rapid increase in use in the late 1960s the drug was seen as a political and generatioLçymhol. Its use became a symbolic gesture of belonging to a particular political and social viewpoint and was interpreted as such by those with opposing views. Marijuana's involvement with the deep social issues of the day made it difficult for many to change their attitudes toward the drug and those who either used it or opposed it.

Another factor in continued marijuana use is that many who are not seeking to make a social or political statement simply find the drug's effects enjoyable. Marijuana use in the late 1970s has become characterized by a quiet expansion of experimental and regular use. While many of the so-called "radicals" of the sixties have been absorbed into society in a variety of mainstream pursuits, the legacy of that turbulent decade continues to influence attitudes toward marijuana. However, the sheer weight of the number of present users has begun to be reflected in legislative reforms and in a reduction of rhetoric from both sides of the marijuana issue. In summary, as the National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse noted in its first report,

For various reasons, marihuana use became a common form of recreation for many middle and upper class college youth. The trend spread across the country, into the colleges and high schools and into the affluent suburbs as well. Use by American servicemen in Vietnam was frequent. In recent years, use of the drug has spanned every social class and geographic region.'*

Frequency of Use and the Future.

While more than one in five of the nation's youth and adults report use of marijuana, only one in twenty have used it more than one hundred times. /By their own subjective measures of use, 3.5 percent of youth report "regular" marijuana use and 11.8 percent occasional use. Regular use among adults is only 2.1 percent, with occasional use at 7.9 percent The overwhelming majority of individuals claim to be nonusers or non-current users (84.6 percent of youth and 89.8 percent of adults); many of these have experimented with marijuana and may have been occasional or regular users at one timer's

While it is impossible to accurately forecast future marijuana use, surveys have been conducted which attempt to determine future 'intentions. Half of present high school seniors say that they would not use marijuana even if it were legally available, yet a majority of young adults age eighteen to twenty-five have reported at least experimenting with it. But even among this latter group, 48 percent say they will definitely not use marijuana in the future.' Among the reasons given for nonuse or cessation of use, simple lack of interest is the overwhelmingly predominant response; fear of legal prosecution does not rank high among the reasons commonly given. Whatever the ultimate percentage of continuing use, marijuana_ smoking is presently a cultural norm for young American adults Nothing in the surveys regarding future intentions would lead to the conclusion that it will disappear or decline to a marked extent in the near future.

Early Legislative Changes: From Felony to Misdemeanor

To understand the policy dilemma of the late sixties and early seventies we need to examine the historical context of marijuana laws. Richard Bonnie and Charles Whitebread, in their history of marijuana prohibition in the United States, describe a fifty-year period extending through the mid-sixties in which there was a social consensus supporting the nation's marijuana laws.18 They attribute this support to the generally accepted beliefs that marijuana was a "narcotic" drug indistinguishable from the opiates and cocaine, that use inevitably became abuse, that it was associated with the lowest levels of the socioeconomic structure where crime, idleness, and other antisocial behavior are common; and that it was perfectly proper to prohibit any personal behavior thought to be incompatible with society's best interests.

Punitive sanctions for marijuana use and possession were most severe in the 1950s. In 1951 Congress amended the Narcotic Drugs Import and Export Act and the Marihuana Tax Act to provide uniform penalties for drug violators.19 This legislation treated marijuana as a naxcatic rug= despite the lack of any pharmacological basis for doing so—and increased penalties for violations to ten to twenty years for third and subsequent offenses, with a $2,000 fine for all offenses; probation and parole were denied for all but first offenses. The Narcotic Control Act of 1956 added to these penalties and established separate penalty provisions for possession and sale.20 Under this act possession of any amount of marijuana brought a minimum sentence of two years for the first offense, five years for the second, and ten years for third and subsequent offenses; the fine for all offenses was raised to $20,000. Conviction for sale of marijuana was punishable by a minimum sentence of five years for first offenses with ten years for second and subsequent offenses or any sale to a minor by an adult. Probation and parole were denied for all except first possession offenders. Every state in the union followed the federal lead at the time, and in some instances provided even harsher penalties.

These stringent penalties coincided with the height of the "Cold War" and concern over foreign, especially communist, subversion. While the primary drug concern during that period was over heroin (believed to be "pushed" by communist Chinese agents in an effort to subvert American youth), marijuana was also indicted, not particularly for its own sake, but because it was held to be a "stepping stone" to other illicit drugs such as heroin.' The fact that marijuana was described by statute as a "narcotic" drug reinforced the theory that its use led inevitably to other drugs. At any rate, the penalty structure established during the 1950s carried over into the 1960s—and from there ran headlong into controversy.

No one can say precisely how and why marijuana came to be associated with the social upheavals of the sixties. From the early civil rights movement in the South to the Free Speech movement in Berkeley to the later antiwar protests, social disobedience on a massive order characterized the new decade, in sharp contrast to the conformist pressures of the 1950s. The veneer of social unanimity on America's goals and values was quickly stripped away by fast-moving events, revealing deep-rooted, emotional differences. Marijuana was a convenient symbol of protest, an available ideological banner, particularly when compared to the use of alcohol by the "establishment". But as marijuana use spread rapidly among white and middle-class youth, especially on college campuses, the attitudes of preceding decades began to change in response.

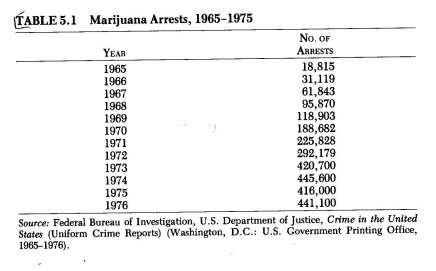

Since 1965, over 2.75 million arrests for marijuana violations have been made by state and local authorities alone, despite consistent assertions by law enforcement officials that marijuana is a low priority. In 1976 there were 441,100 marijuana arrests, compared with less than 19,000 in 1965; the overwhelming majority of these were for possessing, not selling, the drug. By 1976 marijuana arrests were thirty times what they had been in 1965 and had increased as a percentage of all drug arrests from about 40 to 70 percent (Table 5.1).

The rapid growth in arrests, most of which were for simple possession of a small quantity of the drug, reflected the increased involvement of American criminal justice with marijuana. However, despite the dramatic increase in arrests, marijuana increased greatly in popularity during this period, and many of those using it were children of "respectable" middle-class Americans. The thought that their own children were now "criminals" in the eyes of the law slowly began to convince many parents that these laws might be potentially more harmful than the drug itself.

Other costs began to become apparent as well. Legal scholars like John Kaplan and Arthur Hellman expressed their concern that the enforcement of marijuana laws may have had an even more negative impact than alcohol prohibition on the relationship between the American people and their criminal justice and legislative officials.22 Prohibition of use seemed to be applied selectively, as well. Due to their unconventionality, those with long hair ("hippies") seemed to be singled out for application of sanctions. This perception of unequal enforcement of the law alienated a substantial segment of the American people. These feelings of alienation led in some cases—perhaps in many—to active rejection of other laws and social conventions.23 However, other, more far-reaching social issues—racial segregation and an undeclared war in Southeast Asia—also led to the development of attitudes of alienation, and the role of marijuana law enforcement in producing deviant behavior should not be overstated. However, it is clear that the laws and the way they were enforced did contribute significantly to the disaffection of many Americans, particularly the young, with the established order in general.24

Growing awareness of the heavy social costs of penalizing ever-increasing numbers of young Americans prompted widespread legislative reassessment. At the state level, the process of reducing simple possession of marijuana from a felony to a misdemeanor actually began in the mid-1960s, in contrast to federal law, which took until the end of the decade to change. In 1967, just prior to congressional deliberations on a new comprehensive drug statute, the United States became a signatory to the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, an international treaty obligating the signatories to limit all traffic in marijuana and other drugs to that needed for medical and scientific investigation.25 This treaty obligated the United States to restrict the cultivation and distribution of marijuana, but did not require any specific punishment for illegal possession.

In 1969 several congressional committees scheduled hearings, not only on marijuana use but on control of LSD, heroin, and many other psychoactive substances. The result of these hearings and of discussions between the administration, the Senate, and the House of Representatives was the passage in 1970 of the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act.2e The part of the legislation dealing with control, the Controlled Substances Act, provided five regulatory schedules for psychoactive substances depending on their believed harmfulness, potential for abuse, and accepted level of medical use. Criminal penalties for sale and possession were determined by classification, with Schedule I drugs carrying the highest penalties, since they were considered the drugs with the highest abuse potential, highest dependency liability, and no currently accepted medical use. The placement of marijuana in Schedule I beside heroin and LSD was indicative of the continuing strong official attitude against the drug in spite of emerging scientific evidence showing users not to have any physiological dependency liability. In fact, marijuana was known to be less harmful than many substances regulated by lower schedules or unregulated by the act.

However, the Controlled Substances Act did reduce simple possession of small amounts of all the specified illicit drugs to a misdemeanor, and abolished mandatory minimum sentences for all convicted offenders except heavy traffickers. On the state level during the period 1969-72, nearly every jurisdiction also amended its marijuana penalties, so that by 1972 simple possession had been reduced to a misdemeanor in all but eight states, The new federal act also established a National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse, which was to conduct a year-long study on marijuana and its effects and report its findings to the administration, Congress, and the public. As the following material describes, the commission's report set the stage for further legislative changes.

The Beginning of the Decriminalization Debate

The National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse (the "Shafer Commission") was given broad responsibility for examining all aspects of the growth in illicit drug use, particularly of marijuana. Reflecting the highly charged, politicized nature of the drug issue at the time, the commission came under criticism from all sides before it even began its work. Among the criticisms were charges that it was "establishment," that there was only one commission member under forty, and that certain members might be subject to political pressure. On the other hand, President Nixon, who had himself appointed nine of the thirteen members, publicly proclaimed shortly after the commission began its work—amid rumors that some members already had doubts about current criminal policies—that whatever the commission might recommend, he was firmly against relaxing American marijuana laws.27

The Report of the National Commission.

The publication in March 1972 of the first report of the National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse, Marihuana: A Signal of Misunderstanding, provided one of the few dispassionate recent official reviews of marijuana use in American society.28 Despite pressure from both advocates and opponents, the commission achieved a result that resisted their biases. Both the first report and the companion final report, Drug Use in America: Problem in Perspective,E9 are of value as enlightening sources of information and policy analysis on illicit drugs, several years after their publication.

The commission provided the first official recognition of the widespread and pervasive use of marijuana, the use of which was previously assumed to be confined to marginal social groups.It found that use occurred in all socioeconomic groups and occupations, that among adults it was by no means confined to college students, and that although it was highest in cities, towns, and suburbs, it was not uncommon in rural areas,

The commission profiled users, traced the factors involved in becoming one, detailed the effects of marijuana, and delineated the social impact of its use. It concluded that any risk of harm probably lay in the heavy, long-term use of the drug although it lacked evidence even on this risk—and that in terms of social impact ". . . it is unlikely,that in marihuana will affect the future strength, stability or vitality of our social and political institutions. The fundamentaTpïincpies and values upon which the society rests are far too enduring to go up in the smoke of a marihuana cigarette."30 The commission also noted that pi lit rouonse.to marijuana use, according to their national survey, was moving away from approval of jail sentences toward nonpunitive forms of control.31

In reaching its own consensus as to appropriate recommendations for social policy, the commission recognized that, on the one hand, "the use of drugs for pleasure or other non-medical purposes is not inherently irresponsible; alcohol is widely used as an acceptable part of social activities,'' and, on the other, that rsociety should not approve or encourage the recreational use of any drug, in public or private."82 Recognizing that it would be impossible to eliminate marijuana use, the commission formulated the issue thus:

The unresolved question is whether society should try to dissuade its members from using marihuana or should defer entirely to individual judgment in the matter, remaining benignly neutral. We must choose between policies of discouragement and neutrality.33

The commissioners chose a policy some have characterized as one of cautious restraint. While recommending that the sale and distribution of marijuana for profit remain felonies, they recommended thattossession for personal use no longer be a criminal offense and that casual distribution of small amounts of marijuana for little or no remuneration not be a criminal offense.

ss-Roots Forces. Pressure was also building at the local level for reform of marijuana laws, especially in parts of the country where use of the drug had taken hold earliest—California, for example. There, a marijuana lobby group called AMORPHIA was organized in 1969; its membership consisted primarily of self-proclaimed marijuana smokers, and its early focus was legalization of the drug. Though AMORPHIA's position on marijuana law reform was too extreme for most California voters, it did succeed in 1972 in placing on the California ballot a legislative proposition to legalize possession and cultivation of marijuana. That 2.8 million Californians (one-third of the total vote) voted to legalize marijuana in 1972 may be an indication that many voters either were familiar with people who had used marijuana or perhaps had done so themselves.

The most influential private effort in the marijuana law reform drive took shape around 1971—coincidentally, the same year that Congress established the National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse. This group called itself the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML), and sought to influence federal and state legislation through traditional lobbyi tactics. Wishing to broaden the base of support for marijuana law reform, NORML included politicians, physicians, attorneys, civil libertarians, and people from a wide range of other disciplines on its national advisory committee. Former Attorney General Ramsey Clark was perhaps the most prominent early supporter of NORML, and his early recruitment undoubtedly brought others into the organization. While Washington, D.C. was the natural headquarters for NORML—since drug policy was largely the creation of the federal government—it also went to work on the state level, concentrating its early efforts in a few key states.

The partial prohibition approach recommended by the National Commission was unsatisfactory to many. President Nixon saw it only as disguised legalization and reiterated his opposition to any scheme making marijuana less than totally prohibited. NORML viewed the commission's recommendations with skepticism, but accepted that decriminalization was a respectable platform to carry to the states. And there was precedent for such a policy; the Volstead Act had prohibited the manufacture and distribution of alcohol, but shied away from placing criminal penalties on ' private possession for personal use, as did all but five of the states.

The strength of the commission's recommendation to decriminalize marijuana was that it was a moderate response to an issue which had previously been argued emotionally from extreme positions and on the basis of inadequate information. Thus, this form of decriminalization of marijuana was quickly endorsed by many respected national groups, such as the National Council of Churches, the American Public Health Association, the American Bar Association, and the National Education Association. A loose-knit coalition of young activists, former National Commission members and staff, medical researchers, representatives of sympathetic organizations, and even a few chiefs of police and other law officers began to form under the banner of marijuana decriminalization.

Within eighteen months of the issuance of the National Commission's report, Oregon became the first state to adopt legislation decriminalizing marijuana.35 The Oregon statute was similar to the approach recommended by the commission; it officially discouraged marijuana use by the imposition of aeilyiLfine, but eliminated criminai.penalties.and arrest fo>n_ possession ..of-an-eance-or--less, Subsequently, decriminalization—at least in the sense of jail sentences being replaced by fines for personal possession of small amounts—has been adopted by ten other states: Ohio, Alaska, Colorado, Maine, California, Minnesota, Mississippi, North Carolina, New York, and Nebraska. The populations of these states amount to one-third of the total U.S. population; thus one of every three Americans now lives where simple possession of small amounts of marijuana no longer exposes one to criminal arrest and imprisonment.

Despite the cáréfu1lÿ rësearched and caûtiöùsly worded conclusions of the reports of both the National Commission and Canada's Commission of Inquiry into the Non-Medical Use of Drugs (the "LeDain Commission")—reports which actually repudiated many of the myths and questioned other beliefs about marijuana—the debate continues. The cutting edge of the debate is still the disputed evidence on the health and social consequences of use of the drug. Although more is now known about marijuana than many other drugs, there are still wide areas of disagreement among professionals about its effects on health. This continuing disagreement is reflected by the countless articles on the subject which have appeared in both technical and popular journals. Unfortunately, many research studies seem to have been designed to produce a predetermined finding while such findings make headlines, they do little to help the concerned and confused public. The media are also poorly equipped to distinguish between reputable research, research geared to a predetermined end, or that which is frankly inconclusive.

Nonetheless, policymakers must make decisions on the best available evidence. The following section reviews the research reports in those areas receiving the most concern and attention: such medical issues as brain damage, immune response, chromosome breakage, sexual dysfunction, lung damage, tolerance and dependence, psychomotor skills, and marijuana's therapeutic potential; and such social issues as crime and violence, an "amotivational syndrome," or use of other drugs.

Medical Issues

Some medical research about the effects of marijuana seems to have been influenced by the drug's reputation in this country. Although the 1930s film Reefer Madness appears ludicrous today, many of its portrayals of the stereotypical results of marijuana use—insanity, immorality, and crime—find a home in "modern," "scientific" studies of the drug. The legal classification of the drug by the Controlled Substances Act as a Schedule I controlled substance meant, according to the law, that it had no accepted medical use, a high potential for "abuse," and a high probability' of dependency. If one looks at marijuana research over the past ten years, much of that effort seems to have been directed at substantiating this position. Any indication of possible harm to users has frequently been viewed by defenders of the status quo as justification for the stringent controls placed on the drug; in other words, punitive measures against users have been justified on the basis of preventing users from harming themselves. Many still believe marijuana must be proved totally harmless before any policy change can be justified.

Today it appears that marijuana use in moderate amounts over a short term poses far less of a threat to an individual's health than does indiscriminate use of alcohol and tobacco. Millions of dollars have been invested by public and private sources to determine what effects marijuana might be having on the growing number of users; since 1972 the U.S. government alone has given over $25 million in grants for research on marijuana.3° The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), the federal watchdog agency on drug use and misuse, has issued six reports to Congress since 1971 summarizing the hundreds of research reports which have been published during that period. It is significant that research reports by NIDA have not concluded that mariiuana.poses a major publlc health hazard, though NIDA has specifically stated that it feels a duty to call public attention to certain potentially adverse consequences of its continued use. It is also significant that now NIDA is required to produce a marijuana report only every other year instead of annually, which indicates that extreme concern over marijuana use may be receding.

Marijuana research will in all probability never demonstrate harmlessness, nor could research on any psychoactive drug be expected to establish absolute harmlessness. Too little is known about neurophysiology and the central nervous system to.make such expectations realistic. However, enough is now known about marijuana's effects to make a claim of harmlessness specious. Unfortunately, it is evident from the following review of the research that any evidence of physical harm from marijuana -still tends to be regarded as justification for stringent measures to enforce prohibition rather than simply as a reason to discourage and-try to control use.

Many of the scientific studies to date have been merely descriptive of the feelings of intoxication due to marijuana smoking. Common among users are short-term increases in heart rate, reddening of the eyes, drying of the mouth, and dose-related distortions of sensory information—touch, smell, taste, hearing, and vision may become intensified and perceived by many as pleasurable. However, novice users have sometimes experienced acute anxiety characterized by feelings of "losing control" and paranoia which are short-term and transient. Marijuana intoxication can be very subtle, as attested by novice users reporting that they could feel no effects whatsoever from first exposure to low dosages of the drug. Responses_ are also greatlly_.influensed-by-the expectations-ef-tle user-and the settingin which use takes place. The margin of safety in dosage—i.e., from demonstrable toxicity—is enormous; no overdose death has been reported in the United States.

Brain Damage.

There is undisputed evidence that cannabis use produces reversible, dose-related changes in brain waves as measured by electroencephalography. However, these changes are not markedly different from those caused by other psychoactive drugs.37 More sensational reports have described irreversible organic brain damage, alleged to lèad to a permanent behavioral effects such as the "amotivational syndrome." While there is general agreement that marijuana does produce such symptoms as short-term memory loss and time distortion, these disappear as the drug's effects wear off, usually within hour

Studies to date of populations which have long used cannabis preparations have found little evidence of significant harmful effects of continued, heavy use. Separate research projects in Jamaica,38 Costa Rica,39 and Greece40 did not find any evidence of brain damage or impaired mental or physical functioning due to even heavy, chronic cannabis use. Similarly, two independent research teams in the United States—one at the Harvard Medical Schoo141 and one at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis42—sought to replicate the findings of an earlier British , study on brain damage. Both efforts employed a newly developed X-ray technique to scan sections of the human brain. All but one of the heavy marijuana users in both studies were healthy males with no current or antecedent history of neurological disorder or cognitive deficit. The subjects in both studies had also used other drugs, such as alcohol, LSD, amphetamines, and barbiturates. Neither study produced evidence that indicated a structural change in the brain or central nervous system due to heavy, long-term marijuana use; brain damage was not apparent on any of the X-ray scans.

These studies are to be contrasted with earlier reports of brain damage caused by chronic cannabis use. The first such study was reported by a highly respected British medical journal in 1971.43 However, the claims made by that study are extremely doubtful in light of the scientific inadequacies of the research. For example, the ten chronic cannabis smokers observed in the study were described by the authors as "addicts" in terms of their marijuana use, despite the fact that all of them had used LSD at least a few times and the majority had used one or more other powerful drugs, such as amphetamines, barbiturates, mescaline, morphine, and cocaine. (Alcohol was also used, though this fact was, curiously, left out of the discussion on the effects of marijuana.) Simply on the basis of the subjects' own anecdotal reporting of high levels of use of drugs other than marijuana, the designation of cannabis as the sole causative factor in whatever brain atrophy might have been observed is highly suspect.44 In addition, some of the patients suffered from epilepsy, mental retardation, schizophrenia, and past accidental head injuries. All had been brought to the attention of these researchers because of psychiatric difficulties; it seems therefore, as one American psychiatrist has noted, that "these patients are not ideal candidates for this kind of brain research ."45

The British study is not the only suspect research on possible brain damage from marijuana use. The Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) published two articles in 1971 and 1972 by several American psychiatrists who reported their clinical impressions of patients in their psychiatric practice who used marijuana.4ó The first study described a wide range of psychopathological symptoms exhibited, including apathy, mental sluggishness, loss of interest in personal appearance, slowed time sense, difficulty with recent memory, confused verbal responses, ego decompensation, paranoia, sexual promiscuity, depression, and suicidal tendencies, ascribing these symptomatic changes in personality solely to drug use. Further, despite the lack of a systematic history of their patients' drug-using behavior, including alcohol consumption, the researchers concluded that it was unlikely that "any drug other than cannabis could have been the causative agent."47 In those cases where the perceived "symptomatology" of cannabis use persisted after cessation of use, they suggested the "possibility of more permanent structural changes in the cerebral cortex," such as those reported in the British study.48

Another source of highly publicized reports on the effect of heavy marijuana use on the brain has been laboratory animal studies. One such study subjected rhesus monkeys to the equivalent of over one hundred marijuana cigarettes a day for a six-mongh period.49 Not surprisingly, considering the very high dosage of smoked material, two of the monkeys died of lung complications from the smoke forced into them, and a few of the survivors were observed to have behavioral changes described as persistent. However, "permanent brain changes" were neither observed nor claimed by the researchers.50

These findings of "harm" from marijuana, although highly speculative, received wide national medial coverage. They were given even greater prominence and credibility in the hearings of the Senate's Subcommittee on Internal Security, where they seemed to be viewed as an explanation of the disaffection of many American youths, particularly students, with a variety of social institutions and traditional values.51 Reports that questioned the scientific and methodological accuracy of the initial studies, even official ones such as the Third Report to the United States Congress: Marihuana and Health by NIDA52, failed to receive similar widespread public coverage.

Although the research to date does not rule out the possibility of "cerebral atrophy" or other brain damage due to marijuana use, it does seem likely on the basis of the Harvard and Washington University studies and those in Jamaica, Greece, and Costa Rica that demonstrable brain damage is not a normal or probable result of continued cannabis use. In particular, there is at present no evidence to suggest that light or occasional use of cannabis has any permanent harmful effects on brain functioning. This conclusion was reached by NIDA in its 1976 report, Marihuana and Health, which stated, after reviewing overseas studies and other current research, that there is virtually "no evidence of impaired neuropsychologic test performance in humans at dose levels studied so far."53

Immune Response.

During the same period when the "brain damage" reports were appearing came a report by four researchers at Columbia University claiming that a noticeable reduction in the immune response resulted from marijuana use.54 This reduction was said to be comparable to that in cancer and uremia patients, and was interpreted to mean that marijuana smokers would eventually come to lack an essential means of defense against infectious diseases. However, the validity of this claim remains in doubt. The Columbia study was based on in vitro findings (observable in a test tube only); attempts to replicate them and explore their implications by testing for immune-response depression by other means have resulted in contradictory reports.55 To further complicate matters, it has been found that marijuana obtained from illegal sources may figure in a reduction of the type of immune response involving "T-cell" or thymus-dependent lymphocytes. This reduction did not, however, occur in users smoking quality-controlled marijuana;55 thus it may have been the result of some common factor of lifestyle other than marijuana.

As was the case with the brain damage reports, however, the initial "scare" report received the headlines. The results were described by the researchers in a press report as "the first direct evidence of cellular damage from marijuana in man."57 It was immediately suggested that the findings of the National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse be reappraised and that this study provided the "hard facts" desired by legislators and educators wishing to show the harmfulness of continued use of the drug.

The "hard facts" were not immediately forthcoming. The press release on the research preceded publication of the study by several months; thus a considerable period of time passed before the scientific community could examine the research methodology and review the conclusions based upon it. Once the study was published, it prompted strong criticisms from other researchers, and subsequent studies at the Veterans Administration Hospital in Washington, D.C.58 and at UCLA59 failed to corroborate the Columbia study. The UCLA team noted "that chronic marijuana smoking does not produce a gross cellular immune defect.... '80

Missing in the controversy over cannabis inhibiting resistance to infectious diseases is information on whether the users themselves showed signs of increased infection and illness. One skeptic has pointed out,

At colleges, where marijuana use has been documented to include over 50% of the population, one would surely expect the use of the health services to have shown a significant increase. No such increase has been reported. This lack of clinical evidence to support the decrease in immune capacity is particularly striking when one considers how marijuana is used. The ritual of passing a joint from mouth to mouth should be as good a way of spreading infections as anyone could devise. Were effective immune responses interfered with, clinicians should have been seeing a virtual deluge of infections, which is not so.e1

Though some feel the issue of impaired immune response is still unresolved, the fact is that at present, according to the latest HEW report to Congress, there is "no evidence that users of marijuana are more susceptible to such diseases as viral infections and cancer which are known to be associated with lowered production of T-cells."02

Chromosome Alterations and Genetic Damage.

A third health concern that received headline treatment was the furor in 11974 over a report that marijuana use, whether light or heavy, causes chromosome "breaks."63 The press coverage of this research implied that marijuana smoking might cause birth defects similar to those associated with thalidomide. However, once again a further study undertaken shortly after the first was unable to confirm it; there was no discernible increase in chromosome alterations due to either marijuana or two more concentrated forms of cannabis.84 The researchers in the second study concluded, "There does not seem to be any genetic damage produced by the use of marijuana in healthy individuals and without the use of any other drugs. "8`

This conclusion was endorsed by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, which convened two technical conferences on the issue in 1973 and 1974.86 Studies of long-term cannabis use in foreign countries tends to support NIDA's findings.67 Most important to understanding these studies is the fact that the relationship between chromosome alteration and genetic defects is poorly understood. Many substances are known to cause such breaks, including caffeine, aspirin, and Valium. Their effects, if any, on the human fetus are unknown. Despite the absence of positive evidence of genetic breaks due to marijuana use, use of it and most other drugs seem inadvisable during pregnancy, since the possibility of adverse reproductive consequences has not been entirely ruled out by current research.

Sexual Dysfunction.

One other possible health hazard has received substantial press coverage: sexualysfunction,, If one looks back over the years at popular myths about marijuana, one finds that marijuana has commonly been attributed with the power to stimulate sexual drive and lower inhibitions in users. Nothing has been uncovered in the interim which would confirm that marijuana is indeed an aphrodisiac, but it is ironic that the headlines in 1974 dealt with its role in decreased male sexual functioni

A study by the Reproductive Biology Research Foundation in St. Louis, Missouri reported a significant decrease in the plasma testosterone levels of male research subjects from heavy marijuana use.88 A second study by the same research team a year later reached the same result, yet another research effort—this one at Harvard University—failed to replicate the first study's findings. 89

Limitations in both of the St. Louis studies have been pointed out by the researchers themselves as well as by colleagues. Such factors as the small sample tested, the fact that those tested might be using other unreported drugs, and lack of knowledge of the purity or potency of the marijuana used were indicated by the St. Louis researchers.70 Other commentators have noted that testosterone levels normally vary considerably from day to day and even from hour to hour.71 One scientist has pointed out that "it takes a very large decline to affect sexual performance much; even castration has very variable effects on sexual activity in monkeys."72 Still another research team has suggested that "it is possible that a tolerance to marijuana develops that overcomes some inhibitory action of marijuana...."73 Faced with this data, NIDA's fifth annual report to Congress on marijuana and health concluded that the observed decreases in testosterone have still been within what are generally conceded to be normal limits, and that "their biological significance remains in considerable

doubt. "74

In addition to the health issues just discussed, four other less publicized issues deserve examination. These are lung damage, tolerance and dependence, psychomotor skills, and potential therapeutic uses.

Lung Damage.

There is growing evidence that smoking marijuana may have adverse effects on the human pulmonary function. Tetrahydro-cannabinol (THC) and other psychoactive ingredients in marijuana smoke seem to have some of the same effects on the lungs as do tobacco and other kinds of smoke. A study of Jamaican marijuana users showed evidence of a reduction in lung capacity and other pulmonary deficiencies, but those studied were also heavy tobacco users.75 Although tobacco use probably has more severe effects on the lungs than does marijuana, because it is more heavily consumed and does not dilate the bronchial passages as THC does, heavy marijuana smoking may cause similar deficiencies, since, for instance, mari uana smoke is held in the lungs longer to achieve the psychoactive effect

Tolerance and Dependence.

Tolerance to a drug is said to occur when increasingly larger doses must be administered to obtain the same effects observed originally.70 Any such tolerance to marijuana at the dose levels of recreational users is rarely reported, either anecdotally or experimentally. In fact, novice users very often have to use more of the drug to achieve the desired subjective effects than do experienced users who can better identify and are more sensitive to the desired effects. However, a sort of behavioral tolerance has been described which allows an individual to compensate for his or her intoxication and perform certain physical and mental functions which less experienced users would find more difficult or impossible)?

"Addiction" or "drug dependency" implies a permanent physiological change causing an individual to persistently crave the consumption of a particular substance. I i irwtthhel&,-the uses rs wi harawal symptoms, such as chills, pains, restlessness, perspiration, twitching of muscles, nausea, and diarrhea—symptoms which depend on the particular drug and ordinarily subside with time. While the meaning of cannabis dependency is somewhat vague, if defined as a physical dependency manifested by some physical symptoms following cessation of continued use, there is some evidence that it can occur after large THC doses. to the 1975 HEW report, "It should be noted, however, tha t e after effects reported followed unusually high doses of orally administered THC under research ward conditions. Such changes have not commonly been observed in other studies nor has a `withdrawal syndrome' typically been found among users here or abroad. "7B Additionally, the observation of heavy cannabis users in Jamaica79 and Greeceó0 following a period of abstention from use showed none of the typical symptoms associated with withdrawal.

Psychomotor Skills.

There are real and potentially serious risks involved in using cannabis while undertaking a variety of activities requiring exact time and spatial judgments, precise mental and muscular coordination, and constant alertness. Driving a motor vehicle or operating complicated machinery—all potentially hazardous when sober—become more so when intoxicated with marijuana. That conclusion is reached in the Canadian LeDain Commission report on marijuana81, the report of the National Commission on Marihuara and Drug Abuse, and every HEW report to Congress since 1971.

However, it is generally acknowledged that marijuana results in a somewhat lesser impairment than alcohol of fine motor skills, such as those used in driving, because its effects appear to be more subtle and variable.82 Despite these qualifications, impairment of such skills due to marijuana intoxification is clearly indicated by research findings.

Potential Therapeutic Uses.

The idea of marijuana's medical usefulness catches many contemporary Americans by surprise. However, references to the therapeutic use of cannabis can be found as early as the fifteenth century B.c.; it is still used as a folk medicine in many cultures. In this country it was used for a wide variety of ailments throughout the nineteenth century and was referred to in numerous medical publications. In fact, cannabis was contained._inthe .U. Pharmacopoeia until 1941, when it was finally removed because of the difficulties in prescribing it after passage of the Marijuana Tax Act of 1937. The medicinal popularity of cannabis had already begun to decline in the early part of this century, however, due in part to new developments with other drugs. During the period of the early 1940s to the early 1970s medical professionals largely bypassed investigation of marijuana's potential medical uses; then, in the early 1970s, cannabis research, although focused primarily on the possible deleterious effects, began to reveal some possible therapeutic benefits.

For example, marijuana has recently been used to help reduce intra-ocular pressure in the eyes of glaucoma patients. In addition, it has been used experimentally to relieve the pain of cancer patients and reduce or eliminate loss of appetite, nausea, and vomiting following chemotherapy; to relieve asthmatic distress by temporarily dilating the bronchial passages; and to facilitate sleep as a sedative-hypnotic. Other possible uses of marijuana now being investigated are as an antidepressant and in the relief of migraine. If marijuana proves to have antiemetic properties, as investigators now seem to be finding, there may be other possible applications.82

However, in many instances where cannabis has been found to have therapeutic value, its side effects (e.g., increased heart rate) have contraindicated its acceptance by physicians. Though several state legislatures have legalized marijuana for limited therapeutic prescription, it remains pharmaceutically prohibited at the federal level. Synthetic cannabinoids have been developed which in preliminary research do not appear to have bthe disadvantages of natural THC, such as the "undesired" psychic effects and the instability and insolubility of the drug. For glaucoma sufferers, eye-drop preparations containing delta-9-THC have been developed, and are now being tested on laboratory animals, with promising initial results.84

The Controlled Substances Advisory Committee of the Food and Drug Administration is currently considering the merits of rescheduling marijuana to allow for limited medical application. An interagency coordinating committee has recently been established by White House directive under the aegis of the National Institute of Health to reassess the medical efficacy of all controlled substances, specifically marijuana and heroin. Whether or not marijuana or its chemically related synthetics will reach the pharmacists' shelves in the next few years can only be answered by further research and careful evaluation of findings. The Department of Health, Education, and Welfare has observed, "The hemp plant and its derivative chemicals turn out to be neither the best nor the worst of substances. Like everything else it should be used for its beneficial effects and avoided for its noxious aspects."85

Social Issues

Other concerns, whether real or imagined, have also influenced the marijuana debate. It is claimed, for instance, that use of marijuana leads to a loss of desire to work or engage in other meaningful activities. It has also been suggested that it can lead to crime and violence and to the use of other drugs. The following discussion examines these concerns.

"Amotivational Syndrome."

For many years marijuana use, particularly heavy use, has been thought to be associated with an "amotivational syndrome." This belief that use of the drug leads to "a loss of interest in virtually all other activities other than drug use—lethargy, social deterioration and drug preoccupation that might be compared to that of the skid row alcoholic's preoccupation with drinking in the western world"88—draws heavily on the association of marijuana with minorities, lower economic groups, and, more recently, "hippies" and Vietnam War protesters. The public generally has perceived these groups as rejecting traditional societal values, such as the work ethic; it was, therefore, easy to make the assumption that marijuana use was connected to other "dropping out" symptoms.

The Canadian LeDain Commission and the National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse both examined the evidence on the causal relationship between marijuana and loss of traditional motivation. Both found proof lacking. The LeDain Commission concluded, "The role of cannabis in this alleged syndrome is not clear, nor is the research adequate or conclusive."87 The National Commission reached the same conclusion, adding, "The clinician sees only the troubled population of any group. In evaluating a public health concern, the essential element is the proportion of affected persons in the general group."88

More recent studies on the "amotivational syndrome" have failed to confirm its existence. Two separate longitudinal studies of college students on the West Coast were undertaken to determine whether representative samples of marijuana-using student populations differed significantly in performance and adjustment from their nonusing peers; neither study found any difference to exist.B9 In addition, heavily marijuana-using working-class populations have been studied in cultures where extensive cannabis use is traditional. These latter investigations in Jamaica" and Costa Rica,B1 financed by HEW, were designed to compare numerous psychological, social, and health indices among cannabis users and nonusers.

Not only do these studies fail to confirm "amotivational" differences between groups using cannabis and those not using the drug, at least one of the studies indicated that the use of cannabis in one culture was popularly associated with an increase in the aptitude of the user for work.92 That study of Jamaican users of "ganja" (a form of cannabis) concluded,

It would appear that the socio-economic profiles of smokers and controls generated by these data are virtually indistinguishable from each other.... From the self-reported but verified life histories, we are led to at least one conclusion: no negative effect on work history and, therefore, on work motivation due to chronic cannabis use is discernible in this sample.°'

However, there are methodological limitations to this particular study. For example, while complaining about work may be less, efficiency might also be less than for a nonuser. In addition, the cross-cultural studies do not tell much about the effect of marijuana on complex work tasks, as opposed to simple manual labor. Despite these qualifications, no studies have found any marijuana-induced "amotivation."

Use of Other Drugs.

The belief that marijuana use leads to the use of other illicit drugs, such as heroin or cocaine, has its basis in the early public relations efforts of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, beginning in the late 1930s. Marijuana, mislabeled a "narcotic" drug, was labeled a "stepping stone" to other drugs by the bureau. Belief in this claim is common even today; a national poll in May 1977 found a majority of adult Americans convinced that marijuana use leads to "hard drugs."94

Surveys measuring the nature and extent of American drug use do provide some statistical association between the use of marijuana and other illicit drugs. For example, a 1974-75 national survey of the licit and illicit psychoactive drug-using patterns of young American men found that most of those using cocaine, psychedelic drugs, heroin, stimulants, or sedatives also had used marijuana.B5 However, this survey found the same to be true for alcohol. In fact, drug use surveys show that the use of any specific drug can be statistically associated with that of any other drug. This statistical correlation is often confused with the notion that use óf one drug—marijuana, for instance—induces through its pharmacological properties physical changes that impel the user to move on to other drugs. Such pharmacological cause-_and-effect relationship between marijuana and other drugs has never been shown .to. exist. Recent research efforts on the issue of marijuana's involvement with subsequent use of other drugs concur on this point.98 One study of heroin users found that 70 percent had their first drug experience with alcohol, and only 2 percent with marijuana.97

Crime and Violence.

A final issue in the current debate over marijuana's relative harmfulness relates to its role, if any, in the commission of criminal acts. The prevailing opinion in this country through the late 1960s was that marijuana is causally linked with murder, rape, and aggravated assault. Once again, this belief appears to have originated in the campaign of the old Federal Bureau of Narcotics to eliminate the drug from American society.9ß Despite a complete lack of empirical evidence to support this claim, a majority of Americans in 1971 believed that such a relationship did in fact exist; the National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse found that 56 percent of adult Americans believed that "many crimes are committed by persons who are under the influence of marijuana5

While widely held, these public attitudes are erroneous. Both the National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse and the Canadian LeDafn Commission have concluded that there is no evidence whatsoever, in the words of the National Commission, "to support the thesis that the use of marijuana either inevitably or generally causes, leads to or precipitates criminal, violent, aggressive or delinquent behavior of a sexual or non-sexual nature."loo

A more recent study of violent crimes (particularly sexual assault) and the use of psychoactive substances (including both marijuana and alcohol), found alcohol the drug most likely to be associated with serious assaultive and sexual offenses. '91 Alcohol was also selected by the offenders themselves as the drug most likely to increase aggression. In contrast, marijuana was generally believed by offenders to decrease aggressive tendencies. The unanimous conclusion of recent examinations of the commonly presumed marijuana-crime relationship is that no such connection exists.

The Experience of Decriminalization

In spite of the continuing, sometimes acrimonious, debate over marijuana's hazards, several state and local governments have adopted significant policy changes. Eleven states have now decriminalized the possession of marijuana in small amounts (generally an ounce), thus eliminating criminal arrest and judicial proceedings for personal use of the drug. Several local governments, where permitted by state law, have enacted ordinances which similarly treat marijuana possession as a "civil" offense, even though state law does not. The procedure in these jurisdictions operates much like the citation-and-fine procedure for motor-vehicle traffic offenses, minimizing the involvement of the criminal justice system with marijuana possession offenses.

While no state has removed all penalties for personal possession or any criminal penalties for sale or distribution of marijuana, four of the states which have decriminalized some possession have also treated distribution of small amounts for no remuneration in a similar fashion.'°2 Twenty states currently provide for the expungement of arrest and conviction records for certain categories of marijuana use, and discretionary conditional discharge is possible in most states.10'

The judiciary as well as the legislature has become involved in revising marijuana laws. For example, the Alaskan Supreme Court has overturned criminal penalties for personal possession or use of marijuana in the home as a violation of a person's right to privacy.104 The Alaskan court based this ruling on an explicit state constitutional right to privacy in addition to an implicit right to privacy under the federal constitution. While other constitutional challenges have been made to existing marijuana laws, rulings in favor of these challenges have been confined to relatively narrow points; most of the broadly based challenges have been rejected.1°5

Changing attitudes toward the use of criminal law against the marijuana user seem to have influenced local law enforcement authorities. More than half of the 414 cities responding to a 1976 survey by the National League of Cities and the U.S. Conference of Mayors reported that they were moving "toward decriminalization of marijuana or less enforcement of marijuana laws."106 The slight decrease in arrests nationally between 1974 and 1975 may reflect a gradual shift in attitudes (see Table 5.1). Nonetheless, marijuana possession arrests are by far the most common drug arrests in the United States; annual arrests still number over the .4 million mark. Reformers point to this continuing high level as an indication that marijuana law reform is still a critical issue.

Oregon: A Case Study.

The focus of recent legislative debates over the effects of marijuana decriminalization has been the experience of the state of Oregon, now in its fifth year of decriminalization. Proponents and opponents alike have relied heavily upon the evidence of "success" or "failure" in Oregon. While proponents of decriminalization base their arguments on the necessity of reforming the penalty to fit the offense, opponents base their opposition on the grounds that it would promote new and continued use. Supporters of decriminalization have never argued that the policy would reduce marijuana use, but rather that it is a more reasonable way to discourage widespread nonmedical use of the drug. Thus, objective gauges of Oregon's "success" or "failure" have been difficult to construct.

Since one of the initial fears voiced by opponents of marijuana decriminalization has been of a precipitous increase in the number of regular and experimental users, in the amount of marijuana customarily consumed, and in outsiders moving to the state to take advantage of the new law, one measure of success is to look at these factors. Measuring the "humanitarian" aspect of the law is difficult to accomplish in a statistical fashion. Surveys of public opinion concerning approval of the law or a desire to see further legislative changes can give some indication of the law's acceptability. However, the best measure would seem to be the testimony of ordinary citizens and public officials alike on their perceptions of the appropriateness of public policy and the administration of justice regarding marijuana.

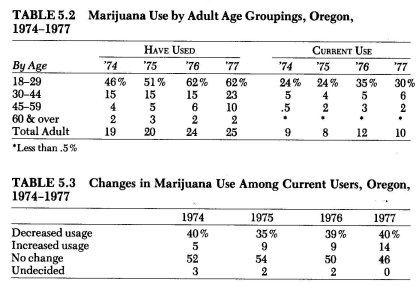

One of the tools used to evaluate the Oregon marijuana law experience has been the public opinion survey. Statewide surveys have been conducted annually from 1974 through 1977 to learn citizen attitudes toward the new law and how or if usage patterns may have changed.107 Examination of these survey results shows that marijuana use in Oregon has remained at levels typical of other western states—(most of which have not "decriminalized" possession)—and national trends generally. Adult Oregonians (over age 18) who have used marijuana have increased from 19 percent of the state population in 1974 to 25 percent in 1977. Significantly, current use of marijuana has remained at a relatively constant level during this four-year period in which experimentation has risen. Although there is no way to validate the reliability of the responses, the majority of current users felt they either had not changed or had decreased their frequency of use, in every year the survey was taken. Another way of looking at these results is to say that 91 percent of Oregon adults did not engage in current use of marijuana in 1974 and 90 percent did not in 1977. Tables 5.2 and 5.3 illustrate the changes in use patterns among various age groupings in the Oregon adult population.

The public's acceptance of the new law can also be seen in the survey results. A majority of Oregon adults consistently favored either the present possession decriminalization or further revisions, such as legalizing sale and use of marijuana. In 1977 only 35 percent of the adults surveyed in Oregon advocated a return of stiffer penalties for possession. Although those who have used marijuana clearly are the most supportive of the legal reforms, those who have never used the drug also favor decriminalization or further revisions over a return to criminal penalties by a 51 to 41 percent margin.

Support for marijuana decriminalization has not had negative political effects for those legislators who supported it. Nor has decriminalization become a significant political issue for campaigning candidates to debate. Rather, the new Oregon law appears to enjoy widespread public support. J. Pat Horton, the district attorney from Eugene and a vocal supporter of marijuana law reform, noted the acceptance of decriminalization by Oregonians in testimony before a U.S. Senate subcommittee.

Acceptance of the new legislation in Oregon has been overwhelmingly positive, especially among middle-aged people who have children in grade, junior high, or the high school level. An attempt by a small number of people in the state to restore criminal penalties for possession was overwhelmingly defeated. Virtually every candidate for office and every incumbent in the State of Oregon, when questioned on the new decriminalization law, has indicated publicly that he favors such legislation and would vote legislatively to continue it.'°t

The Oregon State Office of Legislative Research released an analysis of the law's effects one year after passage.109 Legislative Research attempted to assess the attitudes of law enforcement agencies, courts, clinicians, and prosecutors toward implementation of the new law. Although the response to their mail survey was too low to give a representative reading, the cautious conclusion of the office indicated that decriminalization was having the desired effect.

What evidence there is suggests that decriminalization of marijuana has successfully removed small users or possessors from the criminal justice machinery without relaxing the criminal penalties for pushers or sellers of the drug, and has enabled officials in law enforcement, district attorneys' offices and courts to concentrate on other matters within their jurisdiction. uo

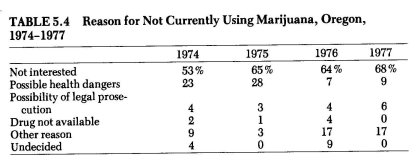

Among the most illuminating findings of the Oregon marijuana surveys were the reasons people gave for not using the drug. Although historically it has been assumed that the criminal law has a powerful deterrent effect, the survey results indicate that fear of legal prosecution played only a minor role in influencing personal decisions on whether to use marijuana. These responses of Oregon adults are similar to responses given in national surveys to the same questions."' Simple lack of interest was consistently given as the reason why most nonusers chose not to use the drug. However, in 1974 and 1975 "possible health dangers" was a frequently cited reason for not using marijuana; it was during this period that many of the reports of serious health hazards were widely publicized. Table 5.4 illustrates the findings.

Another factor in support of marijuana decriminalization is the potential cost saving to government. The Health and Welfare Agency of the state of California undertook a study of the effects of that state's marijuana decriminalization act on the criminal justice system.12 It found, of course, that there had been a substantial reduction in reported marijuana possession offenses, based on comparative 1975 and 1976 arrest and citation data. Total arrests and citations for marijuana possession in the first six months of 1976 decreased 47 percent for adults and 14.8 percent for juveniles, compared to the first six months of 1975; arrests for cultivation also dropped 46.9 percent during that same period, and those for trafficking 5 percent. This decrease in marijuana-related arrests led to a corresponding decrease in police agency and criminal justice costs. Total law enforcement costs for the six-month period dropped to $2.3 million, $5.3 million less than in the comparable period in 1975. Judicial system costs—including prosecution, diversion, and public defender costs—were reduced from $9.4 million in the first half of 1975 to $2 million in the first half of 1976, a difference of $7.4 million. "s

As stated previously, ten more states have followed Oregon's lead in enacting similar legislation reducing the level of the marijuana "simple possession" offense to that of a traffic violation. More than twenty other states are actively considering marijuana decriminalization, and it has been proposed at the federal level by President Carter. The absence of unusually large increases in usage rates in Oregon and the other decriminalized states and the generally high level of public support for these changes once made are persuasive points for those seeking marijuana reforms at federal and state levels.

Yet the debate over marijuana's possible harmfulness continues to be argued as well. Marijuana policy continues to be more concerned with public attitudes and values than with objective consideration of the facts. Medical and scientific research disputes have been used to obfuscate the real issue in the marijuana debate. Far too often, marijuana policy is portrayed as an "all or nothing" choice.

The Future of Marijuana Policy

Persistent use for nearly a decade by large numbers, despite significant attempts to discourage marijuana use, suggests that cannabis use is more than a fad and may well prove to be an enduring cultural pattern in the United States.'"

This statement by the NationaUnstitiite on Drug_Abuse recognizes a fact of modern American life: Marijuana is, has been, and will probably continue to be widely used despite policies designed to prohibit it. The recent trend toward decriminalization seems to reflect a growing attitude that civil fines are more appropriate penalties for marijuana use than criminal sanctions. A 1976 national survey by the National Institute on Drug Abuse indicated that 86 percent of adults were against sending marijuana smokers to jail for first conviction of possession, preferring other alternatives ranging from no penalty to probation and mandatory treatment.15 More recently, a May 1977 Gallup poll found that a majority (53 percent) of Americans felt that possession of small amounts of marijuana should not be treated as a criminal offense, while 41 percent favored retention of criminal sanctions. 118

Even more lenient attitudes toward marijuana laws are seen among the youth who will be reaching voting age in the next few years. A University of Michigan study of the lifestyles and values of youth began monitoring high school seniors in 125 high schools around the country, beginning with the class of 1975.11 Three-fifths of the class of 1976 believed that marijuana should either be legalized or treated as a minor civil offense like a parking violation—"decriminalized". This 61.7 percent was an increase of 9 percent over the class of 1975, where only 52.9 percent approved.

If America's youth and young adults maintain the attitudes they now have, and if marijuana usage remains at its present level or increases in subsequent young adult groups, we can expect to £ind,an_jnereasing.acceptance of marijuana in,h.years ahead. While acceptance of marijuana does not necessarily imply increasing pressure for the removal of all criminal sanctions, that would be a distinct possibility. A national survey in 1974 revealed a sharp division between those who have used marijuana and those who have never tried it in their attitudes toward marijuana law reform.118 Eight of every ten adults who have used the drug favored reducing or eliminating criminal penalties, compared with only three in ten of those who have never used it.

Some observers have suggested further changes in the laws, such as the elimination of penalties for the cultivation of a few cannabis plants for personal consumption."° These suggestions appear less radical as time passes and public opinion surveys record increasing support for the legalization of marijuana. A 1977 Gallup poll showed that support for full-scale legalization had nearly doubled in the period 1972-77; at that it was still favored by only 28 percent of adults nationally.120 Thus while the public remains divided on what would be the proper legal response to marijuana use, it seems to be moving toward more lenient approaches. Considerations of tax revenues to be realized from the legitimate sale of marijuana, as with tobacco products, may also fuel future legislative initiatives on marijuana legalization in a time when many levels of government are financially pressed.