9. Prevalence, Characteristics and Correlates of Cannabis Use in the U.K. Student Population

| Books - Cannabis and Man |

Drug Abuse

9. Prevalence, Characteristics and Correlates of Cannabis Use in the U.K. Student Population

Adele Kosviner, Addiction Research Unit, Institute of Psychiatry, London University.

Attempting to survey characteristics of students with experience of cannabis is becoming increasingly like attempting to survey characteristics of students generally, if not of life. Experience of cannabis is no longer a small minority activity, and by the size and nature of its appeal it has become 'a phenomenon' - or part of one, depending on one's preconceptions. Anything can gain symbolic meaning but we are in danger of our reaction to cannabis being distorted by the degrees of symbolism with which it is variously attributed. It is no longer just cannabis use, but 'a symptom for which man has no inner cure', 'a symbol of the rejection of bourgeois values', 'an indication of underlying pathology', 'the glue to a bohemian subculture'. Thank goodness, sometimes, for pharmacologists, Meanwhile, its very investigation seems to have become a 'meaningful phenomenon' too, with well mannered but determined manoeuvres for possession going on between chauvinists of various disciplines, and protagonists of differing philosophies. Arguments as to the most relevant (and to whom?) theoretical or conceptual framework within which to consider possibly relevant (and to what?) correlates, is the bane or excitement of all social research. Shame that the search for clarity and meaning almost invariably leads to defensiveness and over-brave assertion of one's own perspective. But perhaps that's what being laudably controversial and inter-disciplinary is all about.

It is not the intention of the foregoing to have raised hopes as to any riveting qualities of English student drug surveys. It is merely a reminder (should there be need) that the chosen samples and variables of investigation are, in the main, reflective of these various predilections - from psychiatric referrals to sociology students, from symptoms of confusion and depression to views on the relative merits of violent and non-violent protest.

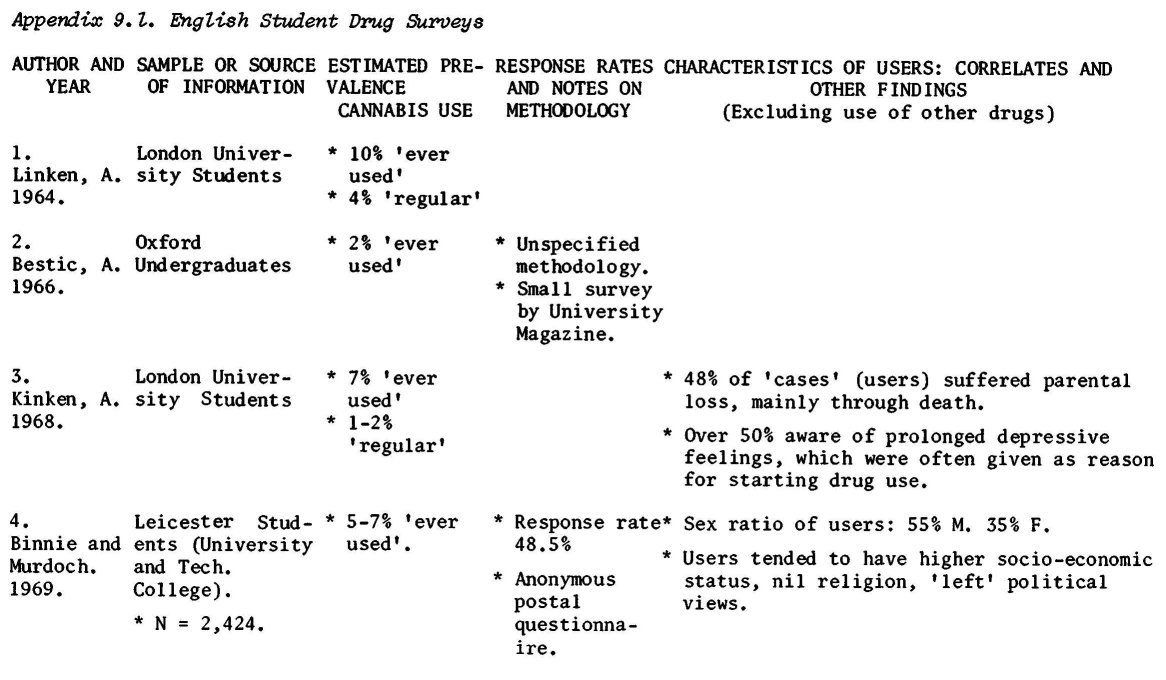

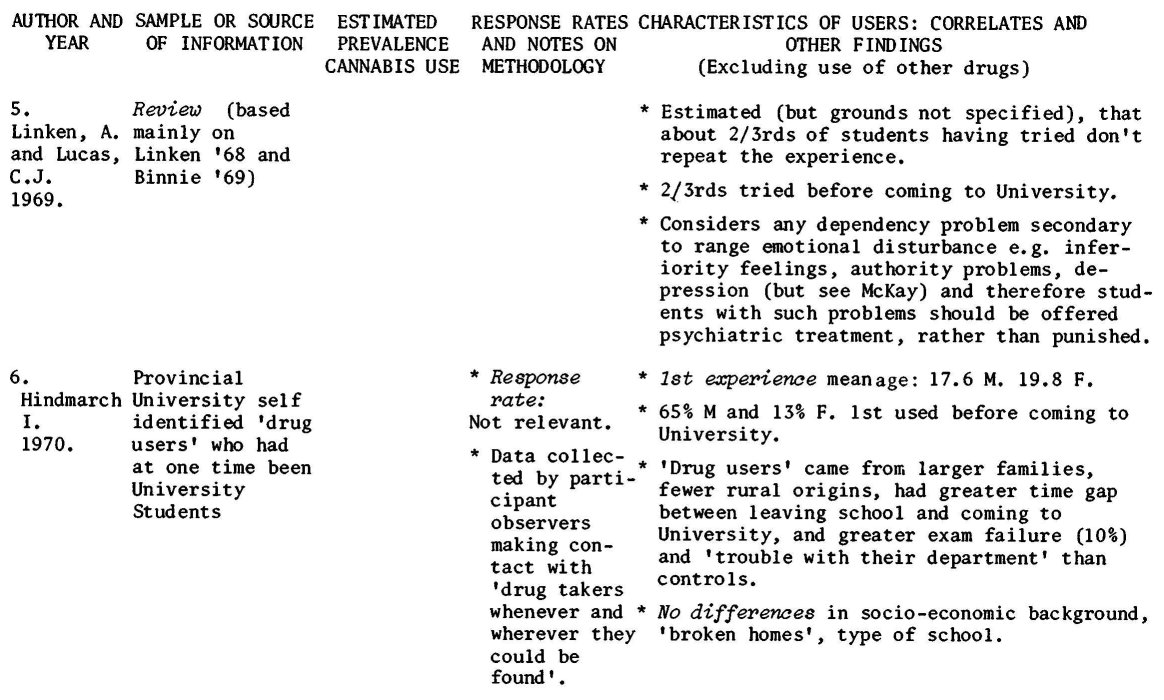

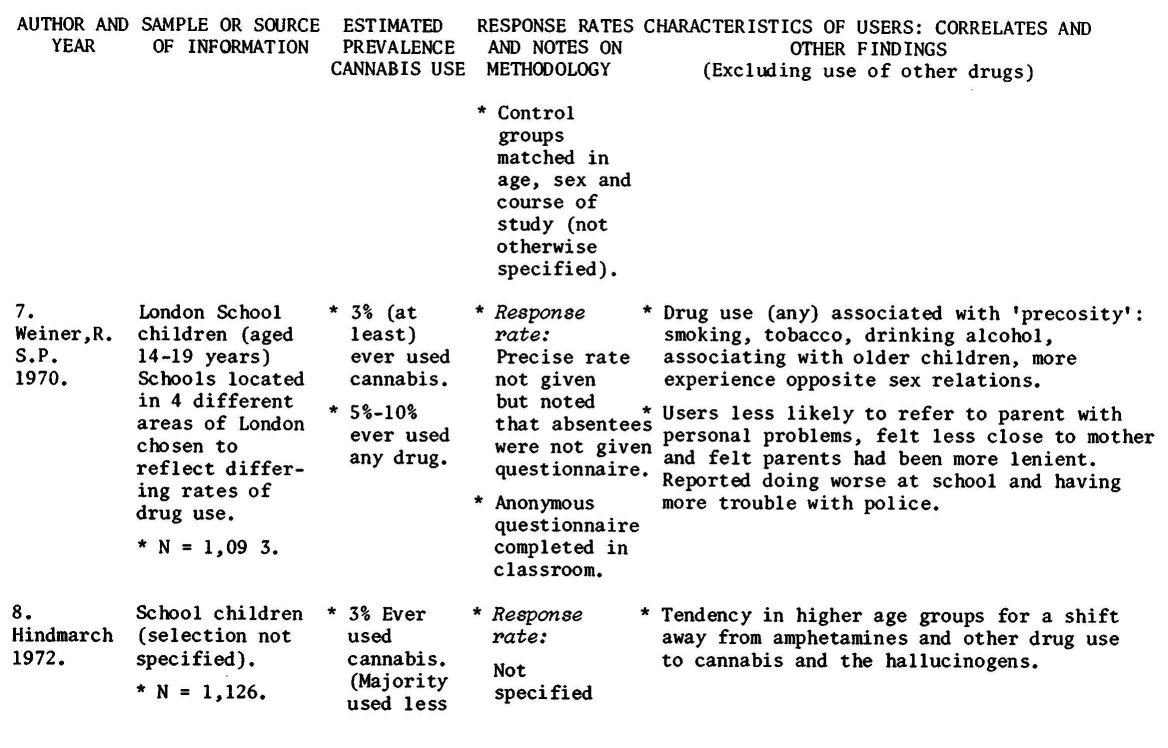

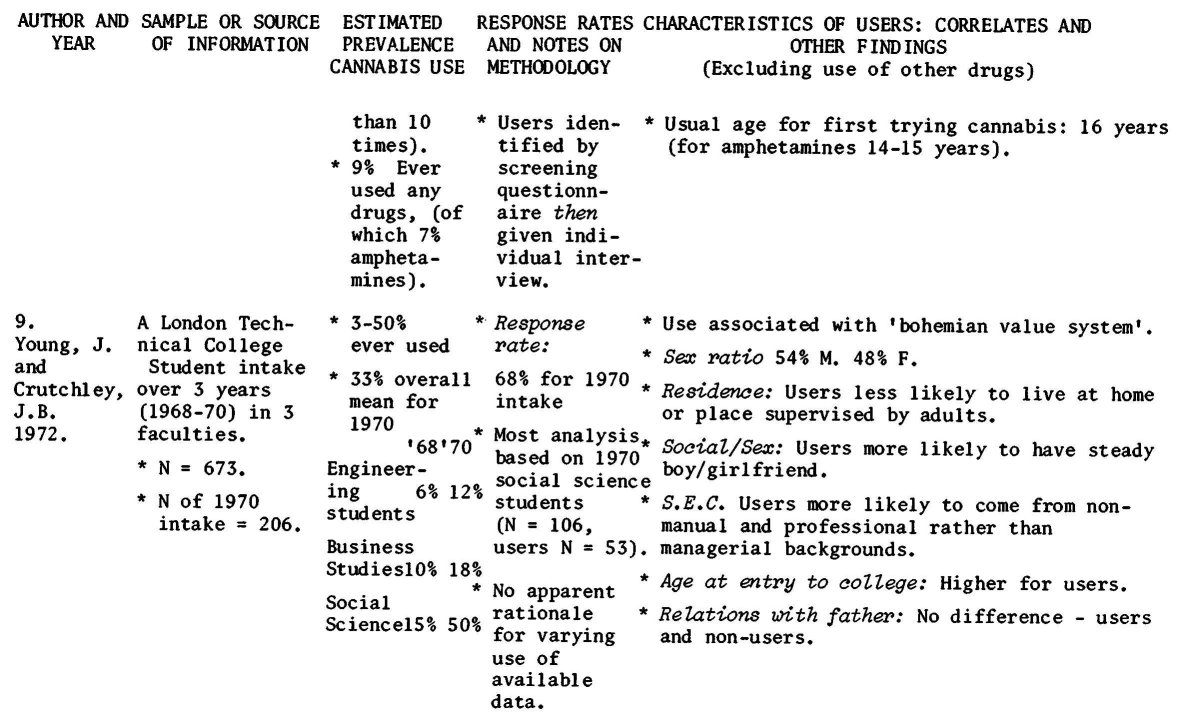

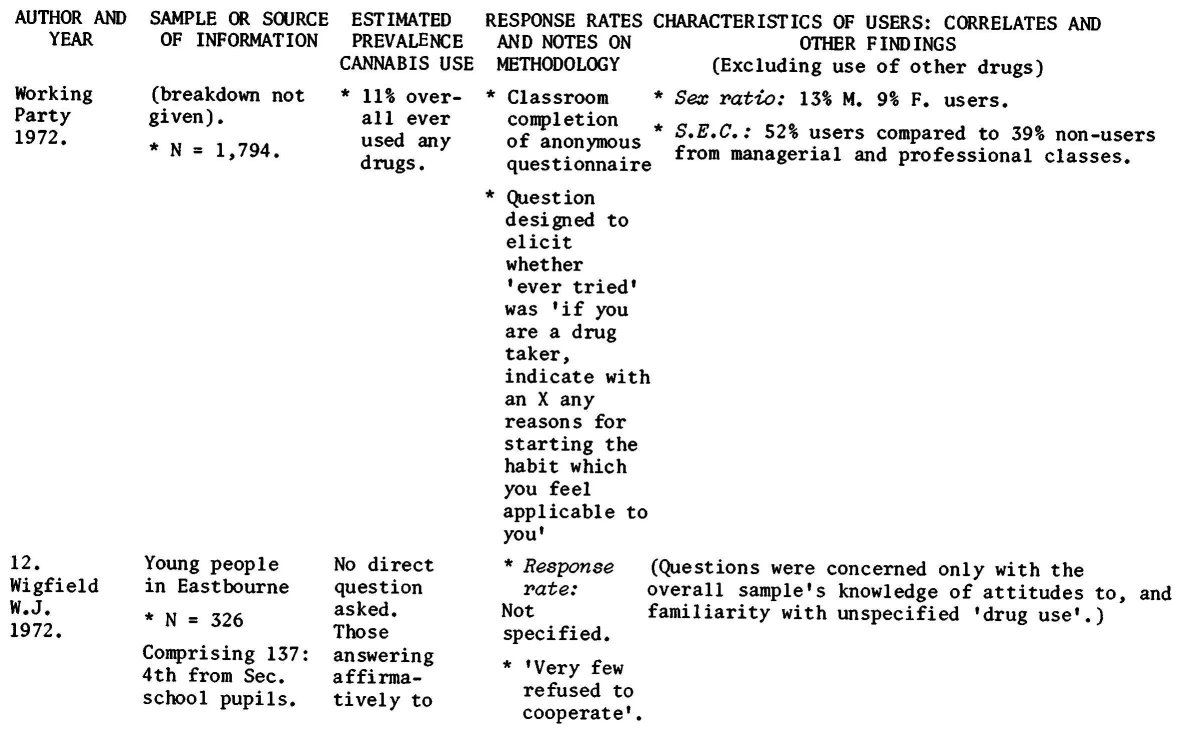

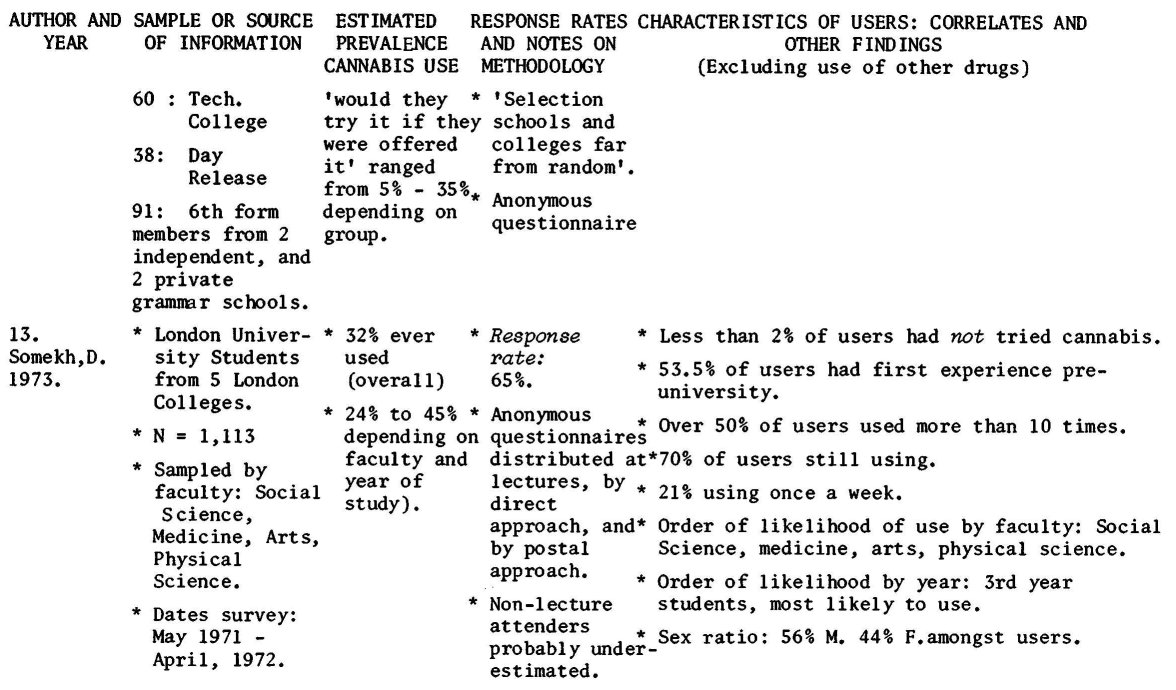

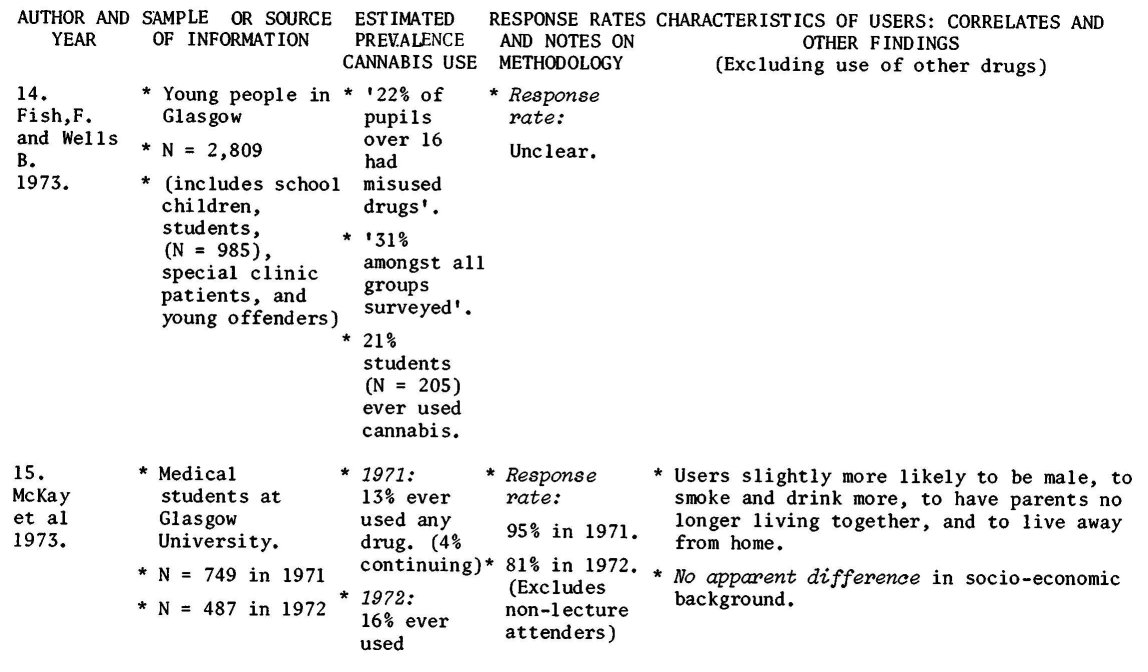

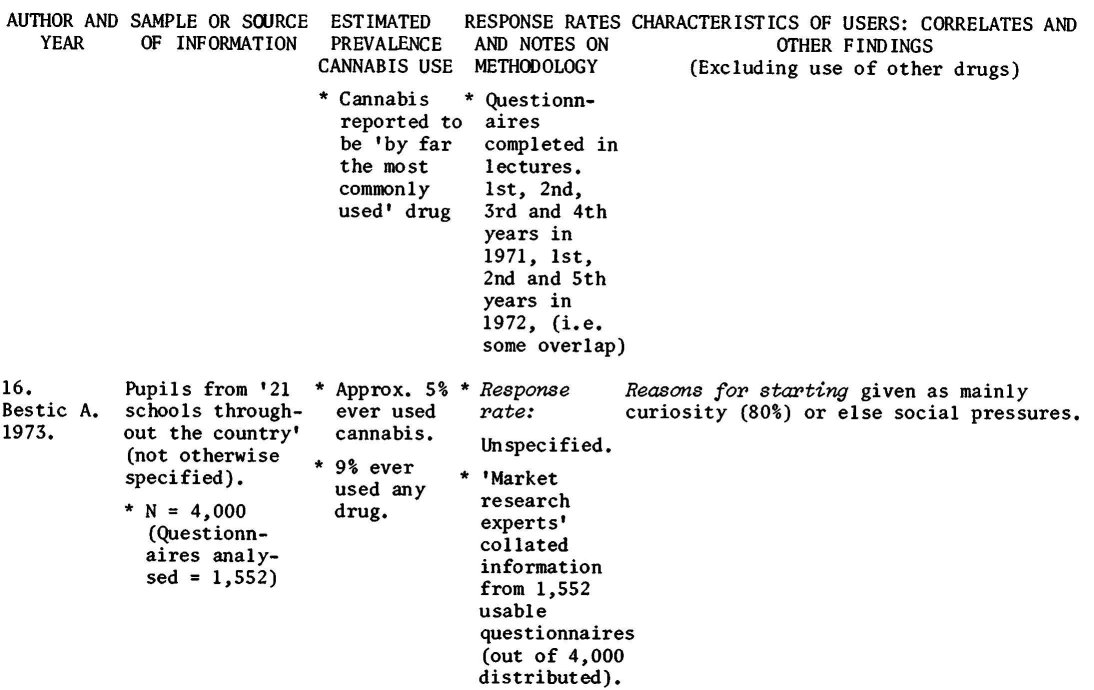

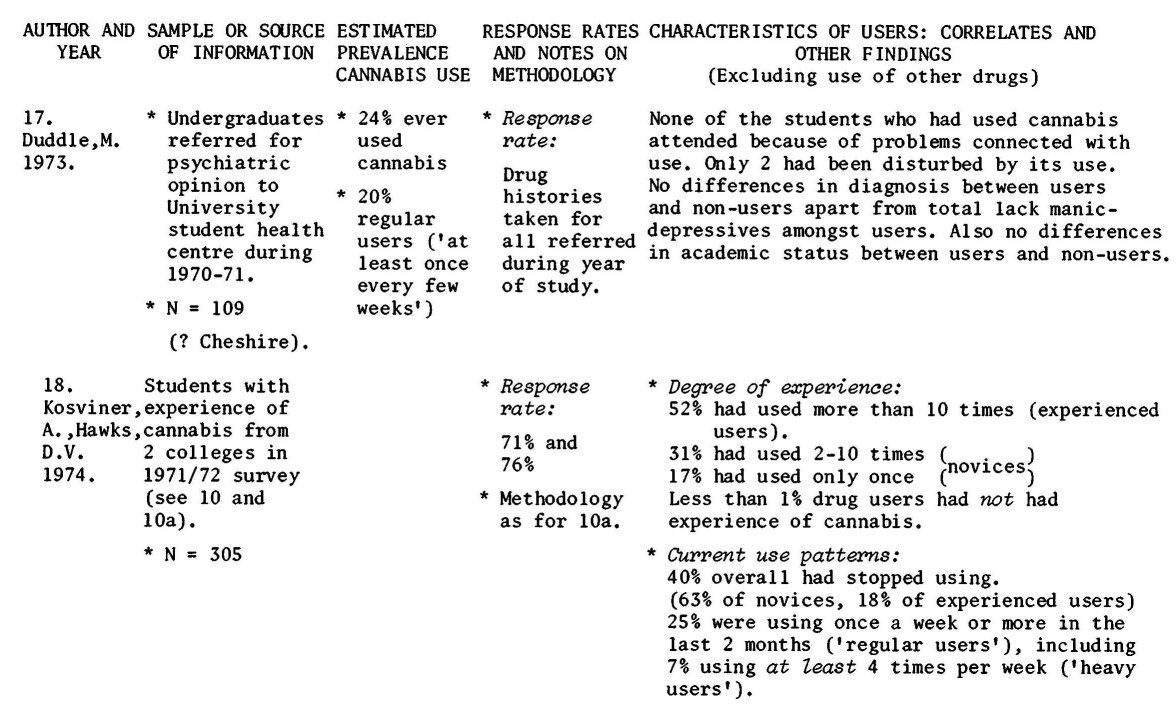

There have been approximately 18 reports of student drug use in the U.K. to date. (This includes three surveys of school children). They range in date of execution from the mid 1960's to the present. In addition to variations in the representativeness of the samples chosen, they range in sample size from just over 100 to just under 8,000; in achieved response rate from under 50 per cent to 100 per cent (but these are, in the main, unspecified); and in ease of access and audience appeal from unpublished reports through Women's Own articles to reports in the drug journals. It is the task of this review to consider what the Nation or Science might have achieved from this somewhat haphazard (if no doubt expensive) counting of heads. I intend firstly to summarize prevalence rates, then to review any common findings as to characteristics and correlates of use, and finally to consider whether there are any well supported indications as to broader contexts in which to view student cannabis use.

The 18 reports are summarized in appendix 9.1, with apologies for any unintentional omissions or misrepresentations.

PREVALENCE

It can be seen from this listing that prevalence rates of cannabis use amongst school children are estimated at between 3-5 per cent, with the higher estimate being the more recent. The overall rates for 'any' drug use amongst school children (the other major drug of misuse being amphetamines) go up to 9 per cent (ever used). Both figures are generally considered to be under estimates, as non-class attenders (where readers are informed at all) are not represented. One study (Hindmarch, 1972) considers that amphetamines are the drug of choice amongst the earlier age groups (the mean age for first use being 14- 15 years), with cannabis being more popular with older children (the mean age of first experience being 16 years).

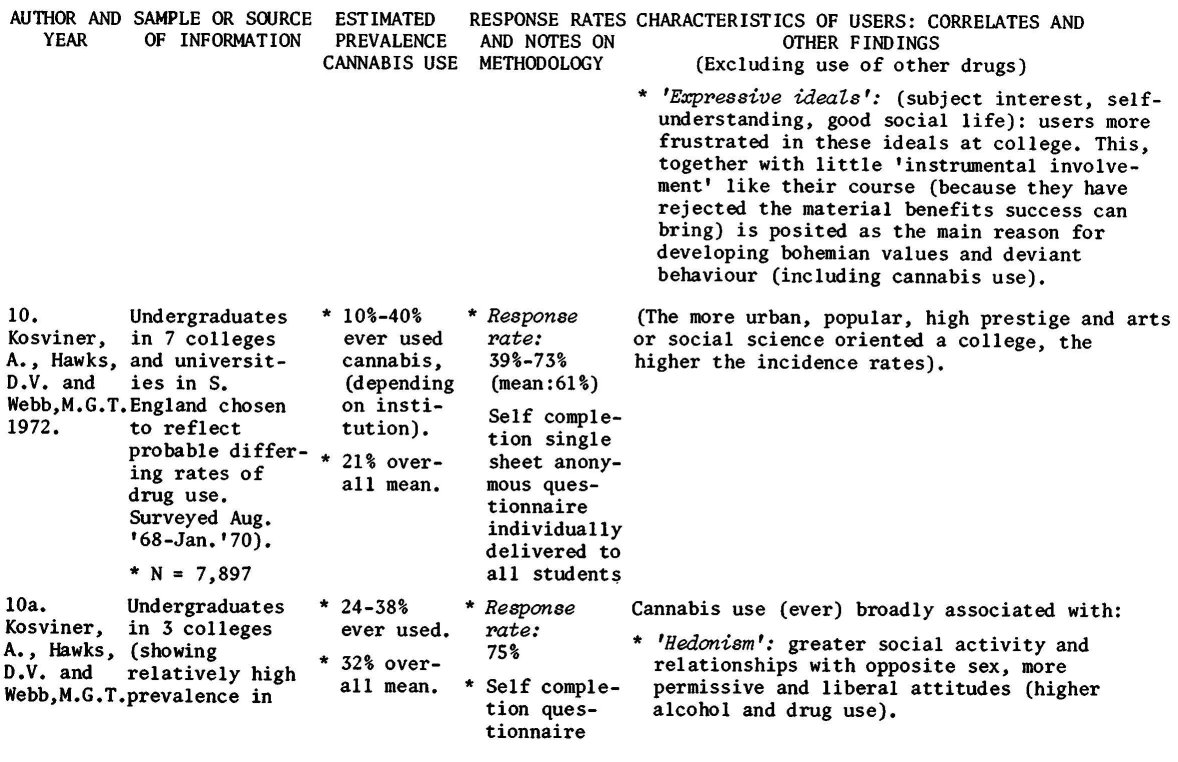

Considering surveys of student drug use the prevalence rates obtained have varied hugely, from 2 per cent to 50 per cent. This is due to a number of reasons including year and type of survey, type and location of college, and type of student. In the earlier reports (published before 1970), the estimated prevalence range was 2 to 10 per cent ever used, with perhaps 1 to 4 per cent counting as (ill defined) 'regular' users. Since then estimates have ranged from 3 to 50 per cent (ever used) but the source of differences are more distinctly attributable. Excluding studies with very biased samples or exceptionally low response rates, the probable range for use within colleges (rather than broken down by faculty) is, on the evidence available, approximately 10 to 40 per cent. This again, if anything, would be an underestimate: time has passed since the last survey taken and there are indications to suggest both that users are over represented amongst non-respondents and that use is perhaps becoming more widespread. (Kosviner and Hawks unpublished data). Rates appear to be highest amongst more urban, popular, prestigeful colleges, and those oriented towards disciplines in which users are over presented. The faculties which appear to reflect higher rates of use are, again on the basis of available evidence; social science, arts and medicine, with physical science, engineering and business studies reflecting lower rates. However if one is looking for an average figure, then considering only those studies of adequate response rate, covering a variety of subject faculties, which are relatively recent and focused on colleges likely to reflect relatively high rates of use (9, 10a, 13), then the mean prevalence rate found was remarkably consistent at around 33 per cent ever used.

CHARACTERISTICS OF USE

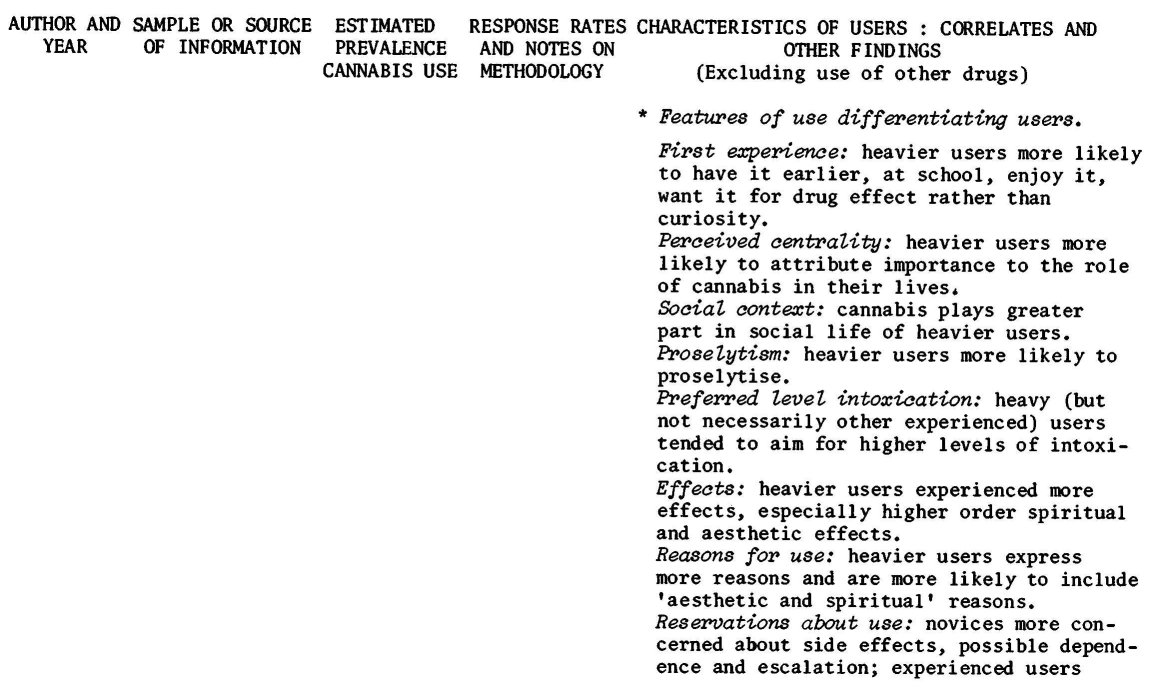

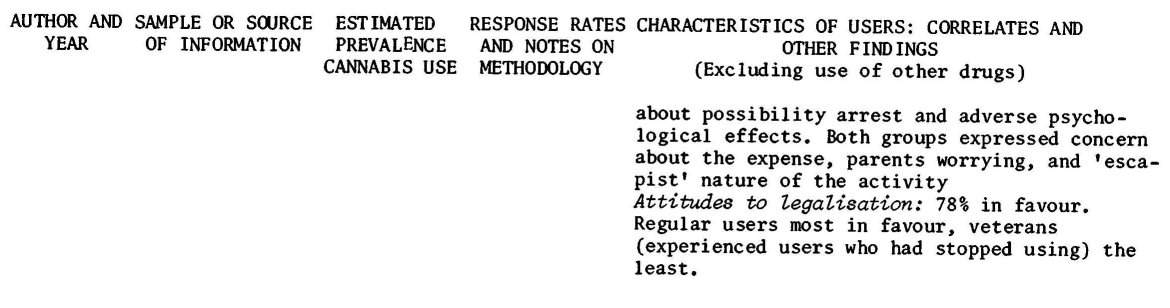

Students with experience of cannabis seem to be divided almost equally into those who have tried it 10 times or less, and those who have tried it more than 10 times (13,18). Those studies reporting information on current (as opposed to 'ever') use (13, 18) suggest that some 60 to 70 per cent of those who have experienced cannabis see themselves as continuing to use it, and 20 to 25 per cent are using it once a week or more. According to one study (18) , the majority of those who stop using the drug do so after very few experiences of it. The drop off rate was 75 per cent for those who smoked only once, 57 per cent for those who had smoked 2-10 times, and 18 per cent for those who had smoked more than 10 times.

Briefly considering other characteristics of student use, it is apparent that the average age for first trying cannabis is in the region of 17 to 19 years and that people who have had experience of cannabis are older at entry to college than their contemporaries who have not. Estimates of the percentage of students who first tried cannabis prior to starting college range from 8 per cent to 65 per cent, with no obvious explanation for the discrepancies. Whilst Dr Somekh will be reporting on the use of other drugs it is perhaps worth mentioning here that cannabis is far and away the most popular drug choice amongst undergraduates, with fewer than 2 per cent of those with any drug experience not having experience of cannabis (10a, 13).

I understand it is not my belief to review details of subjective effects and reasons for cannabis use, but it is perhaps worth mentioning that in this sample, 45 per cent of users said they had experienced some physical ill effects (usually mild), 30 per cent 'nervousness, confusion or panic '; and 25 per cent a 'bad experience' as such. To avoid any appearance of bias it should perhaps be added that 73 per cent reported pronounced feelings of well being.

CORRELATES OF USE

Before attempting to extract any common correlates of use from the studies listed, another note of warning is appropriate, however familiar. Whether one sees the spread of cannabis use in psychological terms of diffusion of innovation or sociological development of sub-cultures; attitudes, expectations and styles of behaviour can spread or develop in the same way. Therefore attribution of causal or even temporal qualities to correlations between drug use and any other particular variable (including demographic or personality features or even drug effects) can be, as many have pointed out, (e.g. 10, 19, 20) a spurious business.

This is not to say, of course, that correlates are not of interest; only that they are to be treated with due respect to their unknown origins. Considering first demographic and background features, a number of studies have investigated association between use and socioeconomic background. Disregarding such niceties as concern for similarity between measuring techniques, three studies have found broad associations between likelihood of having used and higher class origins (4, 9, 11) and three have found no significant differences between users and non-users in this regard (6, 10a, 15). One study (Young, (9)) has placed considerable theoretical importance on finding (uniquely) an association between professional rather than managerial background and likelihood of use amongst social science students. Whilst not at this stage commenting on theory, we are obliged as empiricists at least to note the representativeness and replicability of findings (see Table 9.1, and Appendix 1) in order better to assess any theoretical assertions

based on them.

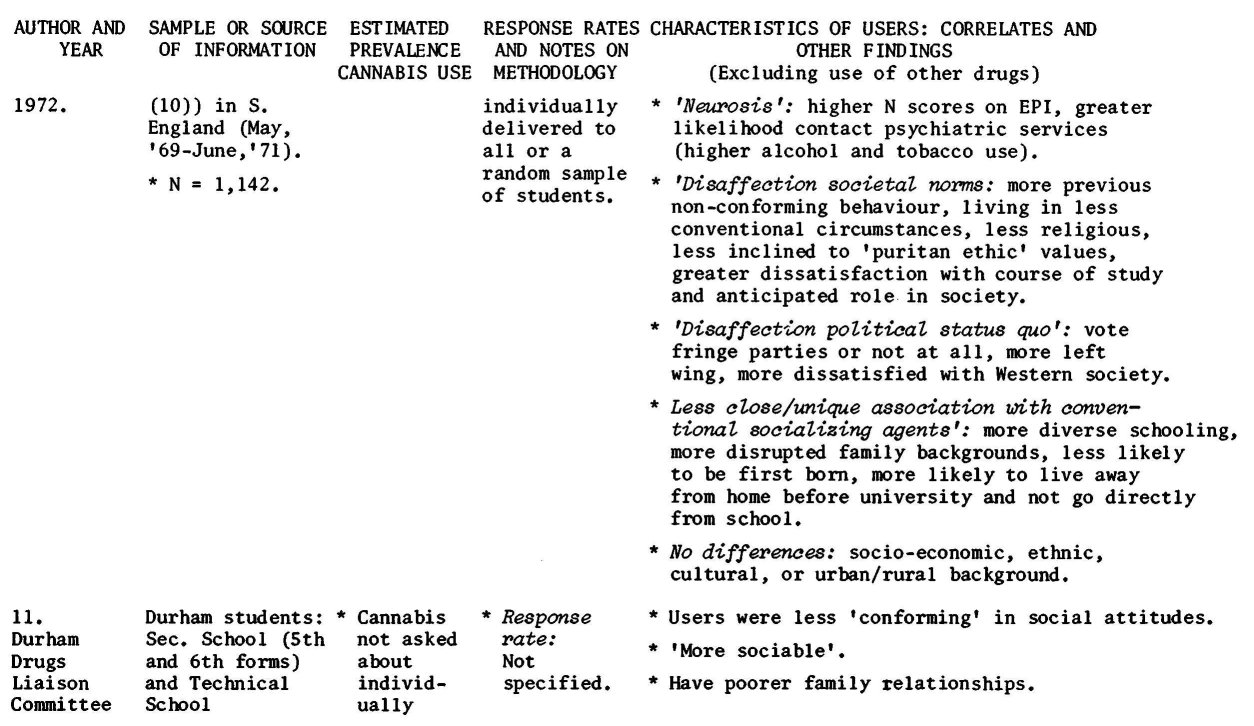

A further area of demographic interest has been sex differences. Again findings vary and it seems that where differences are found they are slight, and in terms of a preponderence of males amongst users (4, 11, 13, 15). Other studies have found no sex differences (9, 10a). It may be that sexual differences balance out as cannabis use moves from being primarily of an innovatory nature to a social one. One study (10a) enquired after birth order and found users less likely to be first born children.

There are conflicting findings on urban vs. rural background, with one study (6) finding fewer users than non-users came from rural backgrounds, another (10a) finding no such differences. As regards type of schooling one study (6) found no differences in school type, another (10a) found a tendency for users to have had more diverse schooling (i.e. changed school more often), and if anything to be more likely to have been to public schools than non-users.

Studies that investigated the students career from school to college (10a, 6) found that users tended to have had a longer time gap between leaving school and starting college. According to three studies (9, 10, 15) users

were also more likely to have lived away from home.

Considering home backgrounds and family relationships, more studies found a higher incidence of 'distress' of some sort in family history or family relations of users (3, 10a, 11, 15) than no such association (6, 9), but the relevant percentage differences are generally small. In the main this has been investigated by enquiring into whether there had been any sort of break in parental relationship due to death or separation (3, 6, 10a, 15), otherwise through questions directly on family relations (9, 10a, 11).

Most studies have included some questions on current attitudinal behavioural and personality correlates, and although in the main these are not directly comparable a few common features are apparent.

Those studies that have enquired into political attitudes (4, 9, 10a) found users over-represented amongst those with 'left wing' and 'fringe' politics. Two studies (9, 10a) found in addition that users were more likely to be active politically (or in favour of it). One of these studies (9) further found that whilst users were consistently more likely to be in favour of non-violent political action (e.g. sit-ins), only social science users were significantly more in favour of violent political action.

Turning to religious views, again all studies investigating this concur on finding users very much less likely to hold current beliefs or more especially be currently active in any religion (4, 9, 10a). Considering general social attitudes, values, and behaviour users have been found to be more hedonistic and likely to have opposite sex relationships (7, 9, 10a) and more active socially (10a, 11). They tend to be more likely to shun what might be called the 'puritan ethic', (10a), and express greater dissatisfaction with their course of

study and anticipated role in society (9, 10a). One of these studies (9) found users more likely to hold what were termed 'expressive ideals' (subject interest, self understanding, good social life) than 'instrumental ideals' (skills to obtain a higher income and job security). Users were also said to be frustrated in their expressive ideals at college. Other studies (10a, 11) found association between cannabis use and general liberal, permissive 'non-conformist' social attitudes. Briefly anticipating Dr Somekh's report it

is relevant to note here that studies which investigated use of alcohol and tobacco (the use of which might be considered partly under a hedonistic umbrella) reported some association with greater use of these drugs and likelihood of cannabis use.

There is very little comparability between the studies in terms of any personality correlates measured. One study (3) found SO per cent of 'cases' were 'aware of prolonged depressive feelings' and the same author later considered any dependency problem to be secondary to a range of emotional disturbances including depression. Another study of a specialised sample of psychiatric referrals (17) found that none of the students had attended because of problems associated with their cannabis use and that the only difference in diagnoses between users and non-users was a total lack of manic-depressives amongst users. In our study we found users tended to

have higher 'N' and 'E' scores on the EPI, to have had more contact with psychiatric services in the past, and to express less 'purpose in life' as measured by Frankl's test. As mentioned earlier other studies have also cited more social activity amongst users.

OVERVIEW AND INDICATIONS OF 'LIFE STYLES'

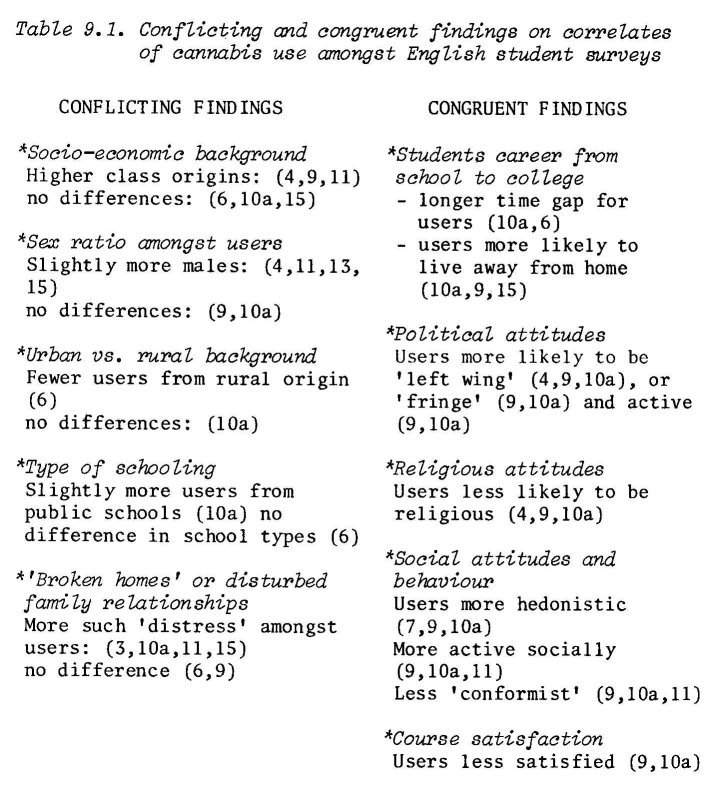

To attempt any synthetic overview of this messy array of correlates runs the risk of that 'over-brave assertion' mentioned earlier. Whenever there is conflicting data, especially from sources of widely differing reliability using widely different measuring techniques, there is a temptation to ignore or belittle that which doesn't fit. To minimize the risk of doing this without due cause, I shall firstly summarize the existing data (with source specified) under two headings: conflicting and congruent (see Table 9.1).

I shall then rely in the main on data from the two recent studies of adequate response rate, clearly specified (and to a degree, heterogeneous) samples, which have attempted to systematically report on variables relevant to consideration of 'life-styles' (9, 10a). However, the findings of other studies will be clearly available for due comparison where there is overlap of relevant data.

Personality. As mentioned earlier there are very few comparable findings. Some indications of higher neurosis and extraversion (10a), less 'purpose in life' and optimism in conventional future (9,10a). Unclear findings on depression (3,17).

As can be seen from Table 9.1 it is the 'harder' demographic and background data that reveal most discrepancies in findings. This is perhaps because a greater variety of studies have included these variables in their investigation. There is considerable congruence on the attitudinal and behavioural data, although of course measurement techniques differed. Further isolated findings (i.e. those that have been investigated by one study) are not included in the table but may be mentioned below.

It seems certainly to be the case that as a generalization, English students who have had experience of cannabis differ as a group from those with no such experience, in terms of having generally more hedonistic, non-conformist, non-religious and 'left' political values and styles of behaviour. They also appear to be if anything, more emotionally disturbed and frustrated with their lot. Analysis of these variables by frequency or heaviness of use would facilitate differentiation of users according to differing balance of these features in their life styles. Meanwhile approximately one third of students in the 'higher-rate' colleges have had experience of cannabis. Until further multi-factorial analyses have been completed, investigation of cannabis use and its correlates is more profitably regarded as investigation of differing patterns of 'life styles' amongst students generally. Cannabis use may certainly play some role amongst some of these, but there is no reason to assume ad hoc that it is of central, or for that matter, peripheral, importance. It may be of interest not so much as a dependent variable, but as a good predictor of other values and behaviours which in turn, may become the 'interesting phenomenon'.

Both studies under consideration (9, 10a) found that use ever was associated consistently with the set of attitudes and behaviours mentioned above. Young termed this a 'bohemian value system'. We: 'hedonism', 'disaffection with societal norms' and 'disaffection with the political status quo'. In addition both studies found indications of frustrations with course of study and anticipated role in society. Young termed this rejecting instrumental values and being frustrated in expressive ideals. We noted less achieved and anticipated 'pay-off' from conformity. It has to be emphasised of course, that these generalisations are rather like 'ideal types' of students, as percentage differences between the groups were not often large.

Young has interpreted his findings in terms of a sub-culture theory emanating from Merton and Matza. In brief he argues that all deviant behaviour has purpose in terms of resolving problems, in particular unachieved aspirations. Those students who have rejected 'instrumental values' from 'official morality' (such as discipline, deferred gratification, caution and reliability) might develop an alternative 'bohemian' value system characterised by more 'expressive', 'subterranean' values such as self expressivity, hedonism, autonomy and impulsivity. Such a value system might well incorporate in the pursuit of its goals the use of cannabis or other drugs that enhance its values of pleasure and expressivity.

That having had experience of cannabis use and holding these sorts of values are broadly associated is not in dispute. There may be more disagreement when considering the importance of individual differences,

how students may come to hold such values, and what other variables might be relevant to understanding student cannabis use.

According to Young, his findings suggest a link between student bohemianism (and therefore cannabis use) and a non-commercial middle class background (i.e. 'professional' value than 'managerial'). He argues that this class has always been critical of 'pecuniary values and instrumentality of the managerial bourgeois class', and that 'it is a short step to conclude that their children....should develop and transform their parents' values' (9).

A quick glance at Appendix 1 shows that out of 6 studies only his own found an association between professional rather than managerial class backgrounds (3 finding no class association at all).

In considering a number of background and developmental variables we found tentative indications that perhaps users had experienced less 'close or unique association with traditional transmitters of societal morality'. (See Appendix 1 for ingredients). But the findings are again by no means unequivocal - disrupted family background is one variable to be found in the 'conflicting' side of Table 9.1.

Young later argues that 'the emergence of marijuana smoking is not a function of family pathology but a bohemian sub-culture which is itself a solution to certain problems of thwarted aspirations faced by students'. I would argue that correlations between variables can be viewed from different angles. Marriages didn't stop breaking up (with varying effect) when subcultures came on the field. Social injustice didn't cease when someone found the meaning of life in a monastery. In an area of so little data, and so much of it conflicting, there is no intellectual need to rule that any one perspective holds the total truth, and that others are irrelevant or misleading. There is a danger of 'the phenomenon' getting treated as a homogeneous thing. In early days of heroin research those searching for a 'typical junkie' got due scoffing. It is boring to be reminded again, whatever one's discipline, that people with experience of cannabis cover a wide spectrum. There isn't going to be an 'explanation' of 'the phenomenon' until it is very much better differentiated within itself. It might be that understanding the development of values is crucial for understanding certain sorts of users, and irrelevant for others. The need for self expression might have to jostle with other 'needs' - from curiosity and affiliation to consistency and identity. Individual differences are important. Factors other than values and thwarted aspirations may be important. If those who, for example, Young says, are less likely to be frustrated in their expressive ideals (sociologists and militants) still rank high amongst cannabis smokers, further levels of explanation are required. It might be that associations found in our study between use and current personality characteristics are spurious, or emanate from a particular subgroup, or hold generally.

It is not easy to remain coldly academic when social action is involved, as with cannabis. It is not 'right' for 'innocent people' to suffer unnecessarily and unwillingly either 'in prison' or from 'adverse drug effects'. We are all presumably eager to minimize injustice, and have to accept that our conception of it differs and that it probably affects our 'scientific' conviction in varying degrees.

To return to the original theme of this paper, we can only try to be aware of the danger of our own tendency to chauvinism, and avoid trying to squeeze the scanty data available into a single model. We can do without another variant on the nature-nurture type of controversy - in this case the individual blown helplessly about either by his own personal pathology or a world of structural pressures.

REFERENCES

1. Linken, A. (1964). In Psychological Aspects of Drug Taking. Proceedings of a one-day conference at University College, Sept., 1964, summarized by Sington, D. Pergamon Press, 1965.

2. Bestic, A. ( 1968). Reported in Turn me on Man, (Ch.8), Tandem Books, London, 1966.

3. Linken, A. (1968). In Adolescent Drug Dependence (Ed.) Wilson, 'The psychosocial aspects of student drug taking'. Pergamon Press, Oxford, 1968.

4. Binnie, H.L. and Murdoch (1969). The attitudes to drugs and drug takers of students at the University and Colleges of Higher Education in an English Midland City. University of Leicester Vaughan Papers, No.14.

5. Linken, A., and Lucas, C.J. (1969). Drug taking among students. Journal of the Medical Women's Federation, October, 1969.

6. Hindmarch, I. (1970). Patterns of drug use in a provincial University. Brit. J. Addict., 1970, 64, pp. 395-402.

7. Weiner, R.S.P. (1970). Drugs and schoolchildren. Longman, 1970.

8. Hindmarch, I. (1972). The patterns of drug abuse amongst school children. Bull. Narcotics, XXIV, No. 3.

9. Young, J. and Crutchley, J.B. et al (1972). Student Drug Use in Drugs in Society, October, 1972. Also 1st and 2nd Annual Reports of Student Culture Project, Aug., 1971 and Nov., 1972.

10. Kosviner, A., Hawks, D.V. and Webb, M.G.T. (1972).

10a. Cannabis use amongst British University Students: I Prevalence rates and differences between students who have tried cannabis and those who have never tried it. Brit. J. Addict., 1973, 69, pp. 35-60.

11. Durham Drugs Liaison Committee (1972). Working Party Preliminary Report. An Enquiry into drug taking carried out among a group of young people in Durham County, July, 1972.

12. Wigfield, W.J. (1972 ). Survey of young people's attitude to drug abuse. Community Medicine, Nov., 1972.

13. Somekh, D. ( 1973). Prevalence of self-reported drug use among London undergraduates. Unpublished report, 1973.

14. Fish, F. and Wells, B. (1973). Reported in Times Educational Supplement. Drugs survey leads to a rethink. April, 1973. Also report in press for Brit. J. Addict.

15. McKay, A.J., Hawthorne, V.M. and McCartney, H.N. (1973). Drug taking among medical students at Glasgow University. Brit. Med. Jour., 1973, 1, p.540.

16. Bestic, A. (1973). Your child and drugs. Woman's Own, Nov., 1973.

17. Duddle, M. (1973). Drug taking amongst emotionally disturbed university students. Brit. J. Addict., 68, 1973, pp.166-169.

18. Kosviner, A. and Hawks, D.V. (1974). Cannabis use amongst British University students: II Patterns of use and attitudes to use amongst users. Draft report, 1974.

19. Blumberg, H.H. Drug taking among children and adolescents. Ch.23, in Recent Developments in Child Psychiatry, M. Rutter and L. Hersov (Eds.). In press, Oxford: Blackwell.

20. Young, J. (1973). Student drug use and middle-class delinquency. In Contemporary Social Problems in Britain. Bailey, R. and Young, S. Lexington Books, 1973.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|