8. Use of Drugs Other than Cannabis and Attitudes to Drugs in U.K. Student Populations

| Books - Cannabis and Man |

Drug Abuse

8. Use of Drugs Other than Cannabis and Attitudes to Drugs in U.K. Student Populations

D. SomeIch, Department of Psychology, Bedford College, London.

In her presentation to this conference Adele Kosviner catalogues 18 or so studies of student drug use, but for the purposes of this paper, only a few of those she mentions will be reviewed. If one selects those studies published since 1970 which are surveys (as opposed to studies of referred groups such as psychiatric cases) and studies which involve young people who are no longer school-children, only five surveys need be referred to, those of Young and Crutchley, Kosviner et al, Somekh, McKay et al and Fish

and Wells.

While cannabis use is the main theme of this conference, among students, as in any other population, there are two additional forms of drug-taking, use of socially approved drugs and use of illicit drugs other than cannabis. A consideration of such drug use may serve to throw more light on the patterns of cannabis use by different sub-groups.

USE OF SOCIALLY APPROVED DRUGS

Use of cigarettes and alcohol by the student population as a whole has been described by Kosviner et al (1973), Somekh (1974), Young and Crutchley (1971) and McKay et al (1973). The first three mentioned studies found that 33 per cent to 48 per cent of students surveyed were smoking cigarettes at the time of the survey. McKay et al reported that 22 per cent of their Glasgow medical students admitted to smoking cigarettes regularly (figures quoted here will refer to McKay et al's second sample, 1971-2).

If those who have ever tried drugs are compared with non drug-users across the four studies, 66 per cent to 77 per cent of users were smoking cigarettes compared to 30 to 33 per cent of non-users. From such figures both Young and Crutchley and McKay et al infer that there is a considerable relationship between tendency to use legal drugs and illicit drug use. This view is reinforced by the findings of Kosviner et al (1974) and Somekh (1974), where drug-users were sub-divided according to degree of drug use. In both cases a strong association between numbers of cigarettes smoked and degree of drug use was found. Kosviner et al reported that only 45 per cent of novice users smoked cigarettes (in Somekh's study a similar category yielded 57 per cent smokers) compared to 74 per cent of the other, more regular users (72 per cent of Somekh's regular users smoked cigarettes). The data available is therefore fairly consistent across studies. A strong association between cigarette smoking and cannabis use, the latter being the principal drug involved, is hardly surprising, as cannabis in this country is most often utilized in the form of cannabis resin, crumbled into tobacco and rolled and smoked as a cigarette. However, there are other possible factors which may influence the relationship between tobacco and cannabis use and these need to be investigated.

When comparing areas which show less consistency in the findings, problems can arise because different studies do not yield exactly comparable data. The available material on student alcohol use illustrates this point. McKay et al report that of students who drank 'regularly' 22 per cent had taken drugs once or more, whereas only 5 per cent of those who did not drink 'regularly' had done so. Young and Crutchley actually state that cannabis users are more likely to drink than non-users although their figures are not impressive:

64 per cent of non-users (N = 34) drank once a week or more compared to 74 per cent (N = 39) of users. Kosviner et al (1973) found that only 8 per cent of users reported that they had never been drunk, compared to 31 per cent of non-users. On the other hand, there were only small differences between users and non-users as to the amount drunk on any one occasion or the frequency of drinking in the previous two months.

These rather unsatisfactory results are partly clarified by two pieces of evidence. Kosviner et al (1973) were the only workers to ask about respondents being drunk. Their findings are extended by Kosviner et al (1974) who reported that approximately 43 per cent regular users had been drunk more than ten times compared to 24 per cent of novice users (and 13 per cent of nonusers), a strong association between excessive alcohol use and regular drug use. This is supported by Somekh (1974) who reported that 12.5 per cent of regular users drank a maximum of 6 or more drinks at any one time compared to only 4 per cent of novice users and 5 per cent of non-users. These findings lead one to speculate regarding the effects of alcohol in users, but the evidence available is not sufficient to allow determination of whether or not cannabis users' responses to alcohol are different to those of non-users.

Secondly, Somekh is the only worker to sub-divide non-users by contact with drugs. When those who had no contact, those who were offered drugs and refused, novice users and heavier users were compared in respect to frequency of drinking and maximum drunk at any one time, it was found that there was little overall differences between the latter three groups. For example, 43 per cent of those who had no contact with drugs drank once or more per week compared to 72 per cent of those who refused drugs, 72 per cent of novice users and 75 per cent of heavier users. Thus it could be postulated that the relationship between drinking and drug use was social rather than related to tendency to use psychotropic substances. This is partly borne out by Kosviner et al (1974)'s finding that significantly more novice users (30 per cent) reported drinking a maximum of six or more drinks at any one time than did regular users (14 per cent), apparently contradicting Somekh's finding, quoted above. However, Somekh has sub-divided heavier users into regular and multi-drug users (heavy users) and found similarly that alcohol use was significantly greater among regular users than among multi-drug (heavy) users. 80 per cent of those classified as regular users (N = 110) drank at least one drink daily as opposed to 60 per cent of heavy users (1 = 90). Thus there is tentative evidence of a 'break-point' in the association beteeen alcohol and cannabis use, with a relative drop-off in alcohol use among the heaviest cannabis users.

To summarize, there is a highly significant association between cigarette smoking and cannabis use among U.K. students but it has yet to be demonstrated whether this relationship has a pharmacological or some other basis. It could be useful to examine the cigarette habit of those who prefer to use cannabis in other ways than smoking it, for example. Those students who do not have any contact with illicit drugs definitely drink less than those who do but among the latter group there seem to be those who use alcohol to excess and those who use illicit drugs to excess, the overlap between these categories being perhaps limited. It may also be that those likely to use illicit drugs are more susceptible to the effects of alcohol.

USE OF ILLICIT DRUGS OTHER THAN CANNABIS

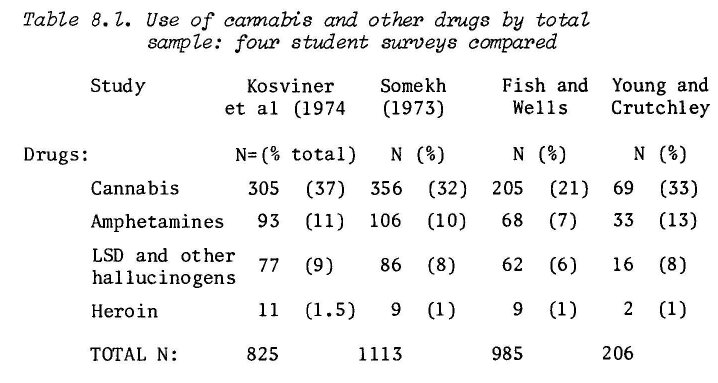

The majority of students who try other illicit drugs have tried cannabis - in Kosviner et al (1973)'s study less than 1 per cent of the sample had only used drugs other than cannabis and Somekh (1973) reported a figure of less than 2 per cent of his total sample in a like category. Table 8.1 shows a comparison of four recent major U.K. studies. The figures show the frequency and percentage of total sample that have ever tried each of the drugs mentioned. They represent approximate comparisons as there are small differences in categories, e.g. Kosviner et al's figure for amphetamine use includes some other pills and the Somekh figure for heroin use includes physeptone.

It can be seen from Table 8.1 that the data from these recent studies (data collected between October 1970 and late 1972) is very consistent, the only discrepancy being the smaller percentage of students in the Fish and Wells (1974) study who reported cannabis and amphetamine use as compared to the other three studies. These minor differences may simply be a matter of geography, the Fish and Wells study being the only one not carried out in Southern England. From Table 8.1 it seems that while 1 in 3 of students who respond have tried cannabis at least once, 1 in 10 have tried amphetamines and 1 in 10 tried hallucinogens, but only 1 in 100 has tried heroin.

Fish and Wells illustrate the patterns of illicit drug use by reference to step-down rates, that is, the percentage of users of each drug who have also used each of the other drugs. Although this presentation does illustrate well known features e.g. that only a proportion of cannabis users have tried LSD and even fewer heroin, while most heroin users have tried nearly every other drug considered, it does not allow specification of drug use profiles. Further, Fish and Wells data for patterns of use does not specify student drug use, only bulked data being given, despite the fact that this involves combining data from rather disparate sample groups.

Kosviner et al (1974) and Somekh (1973) give details of the combinations of drugs used by students. Their categories are more or less the same: thus, 54-56 per cent of users have used cannabis only, 13-14 per cent have used cannabis and amphetamines only, 15 per cent have used cannabis and LSD only, while 12-17 per cent have used cannabis, LSD, opiates and/or other drugs in combination. Furthermore Somekh (1973) has shown that although 40 per cent of those who have used cannabis only have used it more than ten times, 80 per cent of those who have used cannabis and LSD have used cannabis more than ten times and over 90 per cent of hard drug and multi-drug users have used cannabis this often. 22 per cent of drug users had smoked cannabis more than ten times and tried at least one other drug.

From these figures it would seem that experimentation with drugs other than cannabis occurs in about 50 per cent of student drug take; § as a whole and about 60 per cent of regular users. The common drugs involved are amphetamines and LSD and while regular use of cannabis is associated with experimentation with other drugs, including opiates, there is also a substantial group of regular cannabis users who do not experiment with other drugs.

ATTITUDES TO DRUGS

Attitudes to cannabis as well as other drugs have been examined in users and non-users. Binnie and Murdoch (1969) inquired into respondents' attitudes to particular drugs from the point of view of risk to mental and physical health, accuracy of public attitude and adequacy of present legal controls. They found agreement between users and non-users in respect to alcohol, tobacco and opiates. User here means a person who has ever experimented with any drug. In respect to cannabis, users' attitudes were consistently more favourable. With regard to LSD and amphetamines, there was agreement on the extent of health risk, in that both users and non-users felt that LSD was dangerous and amphetamines were not, but for both drugs users felt more strongly than non-users that legal controls were too severe.

Young and Crutchley found a consistent difference between users and non-users of cannabis with their 106 social science students, fewer non-users agreeing that cannabis should be legalized, and more agreeing that cannabis is addictive or leads to heroin use. These findings could be interpreted either as a cognitive dissonance type response by cannabis users or simply that their information i.e. from experience, was more accurate.

** defined simply in this context as those who have used cannabis more than ten times.

Kosviner et al ( 1973) asked users and non-users of cannabis to evaluate the drug and answers tended to suggest that respondents' answers were less categorical if they had had experience of the drug. Greater knowledge of the drug seemed to produce more differentiated answers, something not evident from Young and Crutchley's data. Cannabis users and non-users differed little in their attitudes to injecting drugs, as Binnie and Murdoch found. Kosviner et al (1974) further analysed the attitudes of sub-groups of cannabis users. Evaluation of cannabis did tend to be more positive, the greater the use. Similarly, heavy users were more in favour of legalization. There were no differences between groups in respect to contact with and attitude to injectable drugs.

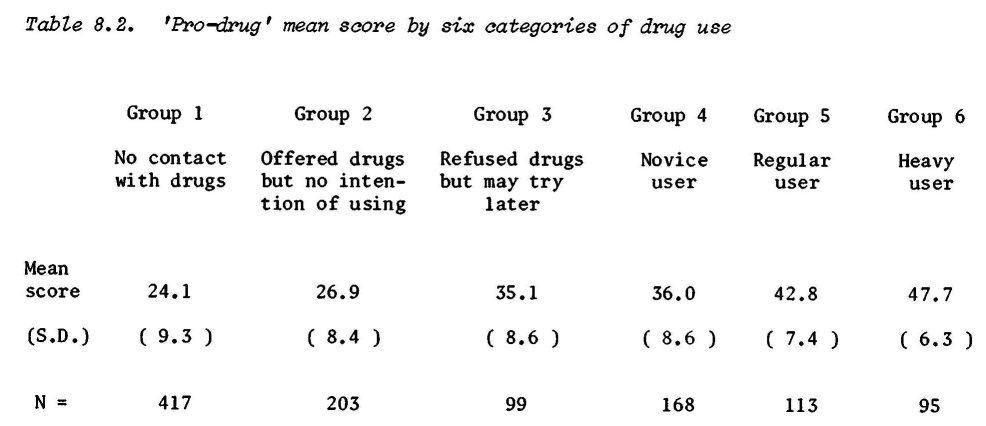

Somekh (1974) used a 25 question attitude section, each question being answered on a 5 point Likert scale ranging from Strongly Agree to Strongly Disagree. This enabled attitudes to be assessed quantitatively, as the scores for 17 questions were summed to give a 'pro-drug' or drug-favorability score for each subject. When subjects were sub-divided into groups of ascending drug involvement, a clear trend in mean 'pro-drug' score was obtained (Table 8.2).

The biggest differences in means were between groups 2 and 3 (demarcating non-users from possible users) and between groups 4 and 5 (demarcating experiments from regular users). Attitude scores were checked for split half reliability within groups using the Guttman formula and values of rll between 0.75 and 0.85 were obtained, that for the whole sample of 1113 being rll = 0.90.

An attempt was made to assess the validity of such a drug involvement score by comparing attitudes to specific drugs with actual use of those drugs. As had been found by other workers, attitudes to cannabis were more favourable, the heavier the use of the drug. Attitudes to LSD showed a similar pattern with non-drug users having a mean score of 4.31 (over 3 questions, maximum LSD-favourable score: 12.00), non- LSD using drug-users 6.15 and LSD users 8.38. Within LSD users (N = 86), 23 who had used hallucinogens once only had a mean score of 7.83 while 21 who had used hallucinogens more than 10 times yielded a mean score of 9.51. Greater involvement with a particular drug therefore gives rise to higher s cores on questions specific to that drug, although it is impossible to say whether this is because the particular drug is viewed more favourably or that this reflects greater overall drug involvement. The fact that multiple drug users in Somekh's survey were the heaviest cannabis users suggests that the two factors go hand in hand and this is borne out by the fact that over 85 per cent of those who had used LSD more than ten times were also to be found among the multiple drug users. It would seem that Somekh's attitude questions have a degree of face validity and that the attitude questionnaire might prove useful in the assessment of the effects of drug education films and the like.

THE USE OF UNIVERSITY STUDENTS AS SUBJECTS FOR SURVEY

Adele Kosviner, in her paper, has spoken of the study of the student drug taker as approximately to a description of students in general. It seems worthwhile to follow up her point briefly by looking at the appropriateness of using students as a specific survey group.

There are two basic disadvantages involved in surveying students, the first being that this results in a 'focussing'phenomenon in that, subsequently, results may be interpreted as if students were the only young people engaged in the behaviour studied. This, despite the fact that (a) the origins of the behaviour lie, in many instances, in a much earlier environment, i.e. school, common to all young people and (b) there is nothing to suggest that drug involvement among non-students is any smaller, rather students are likely, e.g. to be less opiate-involved because of such behaviour being incompatible with life as a student. The other disadvantage is that students are undoubtedly over-exposed to such enquiry methods. This means that students are very often sick and tired of filling in forms and hardly qualify as naive subjects, as many probably have developed their own form-filling set. These disadvantages can be disposed of, to some extent. Students are over-exposed because there are definite advantages in studying them. With students we have a circumscribed group, easier to reach and more approachable than most and the behaviour to be studied can be related to specific aspects of their environment, similar for many students and hence likely to be generalizable within certain limits. The point about focussing is important as it forces us to reconsider the purposes of the investigation - why are we asking?

The main reason for wanting to know something about 'how many?' and 'which drugs?' is to confirm the order of magnitude of the situation, little more, so that sensational guesses can be obviated. The essence of the question 'why drugs?' on the other hand may be to provide a reliable (and hopefully valid) description of the student drug taker in relation both to his or her membership of the group 'students' and the group 'drug-takers' and provide corresponding descriptions of students who are not involved with drugs. In doing this, whole focussing on students in a possibly undesirable way, we may hope to provide a paradigm for consideration of other members of more than one group, e.g. delinquent drug-users. In both these examples, membership of one group is not a necessary condition for membership of the other but membership of both groups may produce an interaction which is useful for the investigation of processes underlying membership of either or both groups.

Students who live at home illustrate this notion. Several workers have found that students who live at home during term-time are less drug involved than those who live away. For example, Somekh (1974) states that nearly a quarter of students who had no contact with drugs

lived at home during term-time as opposed to only 8 per cent of drug users. The danger here is the temptation to use such a finding in a simplistic way, which Young and Crutchley seem to have done. They support their hypothesis that marijuana use is related to social maturity rather than immaturity by quoting the student living at home as an example of the social isolate who is therefore less likely to use marijuana. In fact the case of the student living at home bears a much more complex relation to student life, as Brothers and Hatch (1971) have shown. Brothers and Hatch found that students living at home during term-time were less satisfied with university life, more highly motivated to achieve success and yet differed only very slightly from hall-based students in respect to contact with staff, participation in student activities and extent of university-based friendships.

The point being laboured is that when data from student surveys is interpreted at over and above the most basic demographic level, student status itself becomes a confounding variable. Once this is recognized, however, and the characteristics of student drug use are examined using the premise that student drug use represents the interaction between student status and drug-taking status, a greater understanding of both of these phenomena becomes possible.

REFERENCES

Binnie, H.L. and Murdock, G. (1969). The attitudes to drugs and drug takers of students at the University and Colleges of Higher Education in an English Midland City : Vaughan Papers No. 14: University of Leicester.

Brothers, J. and Hatch, S. (eds) (1971). Residence and Student Life. Tavistock Publications, London.

Fish, F. and Wells, B.W.P. (1974). Prevalence of drug misuse among young people in Glasgow, 1970-72. Brit. J. Addict. (in press).

Kosviner, A., Hawks, D. and Webb, M.G.T. (1973). Cannabis use amongst British university students: 1 Prevalence rates and differences between students who have tried cannabis and those who have never tried it. Brit. J. Addict. 69 : 35-60.

Kosviner, A., Hawks, D. and Webb, M.G.T. (1974). Cannabis Use amongst British University Students: 11 Patterns of Use and Attitudes to Use Amongst Users. (Draft report - unpublished).

McKay, A.J., Hawthorne, V.M. and McCartney, H.N. (1973). Drug-taking among Medical Students at Glasgow University. B 1 : 540-543.

Somekh, D.E. (1973). Prevalence of self reported drug use among London undergraduates (unpublished report).

Somekh, D.E. (1975). A survey of self-reported drug use among London undergraduates. 1971-2. (in press).

Young, J. and Crutchley, J.B. (1971). Student cultureproject: (Enfield Polytechnic) first annual report submitted to the Social Science Research Council (unpublished).

DISCUSSION

CANNABIS AND ALCOHOL

Dr Hawks said 'it has been demonstrated in one or two studies that there is an association between cannabis use and heavy use of tobacco, suggesting that there is some predisposition towards use of licit and illicit drugs. Whilst the excessive use of alcohol may not be associated with the excessive and concurrent use of cannabis, there is some evidence that people who now use cannabis have in the past been heavy users of alcohol. There is the possibility that alcohol use amongst those people currently smoking cannabis is suppressed because of the potentiating effect of the two drugs.'

Dr Miller spoke of the need for studies to differentiate between-subject at a single point of time and within-subject behaviour over time. If one divides studies according to whether they are describing between-subject correlation at a single time or within-subject correlation over time, then one sees that the within-subject data points towards a decrease in alcohol use with onset of cannabis use. 'As far as I know the statement often made that cannabis merely adds to alcohol use is without substance: not one good study addresses itself to that question. What we need here is prospective research.'

Dr Rubin offered some information on use of cannabis and other drugs in Jamaica; there tend to be fewer cigarette smokers among non-cannabis smokers. Cannabis smokers tend to drink less alcohol than non-smokers. Also, cannabis tends to be used quasi-medically instead of prescription drugs - it is an all-purpose drug. Nor is there significant use of any other drug such as heroin in Jamaica.

Dr Edwards asked to what extent alcohol and cannabis were substitutable for each other, and suggested that knowing this could tell us quite a lot about the meaning and purpose of the behaviour. 'I'm particularly interested in Kosviner's finding that the heavier cannabis users are the ones who are more often getting drunk. I would be interested to know whether cannabis users were more skilled at getting drunk - getting drunk requires a certain skill just as getting high does. Perhaps the cannabis user, when he does drink, uses drink in a special way. As well as the expensive prospective studies, we can look at the history of drug use of young people with drinking problems, compared with a control group of those without drinking problems. We should look particularly at the motivations, as well as the frequencies, of the behaviour'.

Dr Tinklenberg spoke of the cycle of drug use that could sometimes be seen in individuals. There tends to be a period of quite extensive drug use, with a preference for stimulants in adolescence and early twenties. As they get older there may be a levelling off for most of the population. So in considering whether drugs will be addictive or not, we have to specify a stage in the life cycle.

CANNABIS AND TOBACCO

It was agreed that, with the exception of North America where marijuana is typically smoked alone, cannabis resin is smoked together with tobacco in most parts of the world.

Both cannabis and opium were used alone before the introduction of tobacco into the East, but they were now often used with tobacco.

Professor Paton pointed out that vomiting, salivation, slowing of the pulse or tachycardia, raised blood pressure, antidiuretic effect, and fainting were possible effects of tobacco. Among the physiological effects attributed to cannabis are tachycardia, diuretic effect and sometimes vomiting and fainting. Thus many cannabis effects might be masked or distorted by tobacco effects if the two are taken together. Dr Miles reported that he had good data showing that cardiovascular tolerance to cannabis develops over a period of 70 days. If the subject is then deprived of cannabis for a long time and then given a small dose of cannabis there is a marked rise in blood pressure.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|