2. Psychomotor and Cognitive Deficits

| Books - Cannabis and Man |

Drug Abuse

2. Psychomotor and Cognitive Deficits Associated with Long- and Short-term Cannabis Consumption: Comparison of Research Findings and Discussion of Selected Extrapolations

M. I. Soueif, Professor and Chairman, Psychology Department, Cairo University.

About four centuries ago the Arabic pharmacopoeia of Daoud Al-Entakui underlined, among other effects of cannabis, lethargy and sensory debilitation (Soueif, 1972). In the fall of 1957 we were just commencing our

exploratory studies on the psychosocial aspects of chronic cannabis consumption. We were, then, struck by the frequency of remarks made by takers and non-takers as well, and by the abundance of hints in various kinds of folklore (eg. Arabian Nights) and anecdotes, emphasizing the psychomotor and cognitive dysfunctions usually shown by hashish users. In the pilot study we conducted from 1960

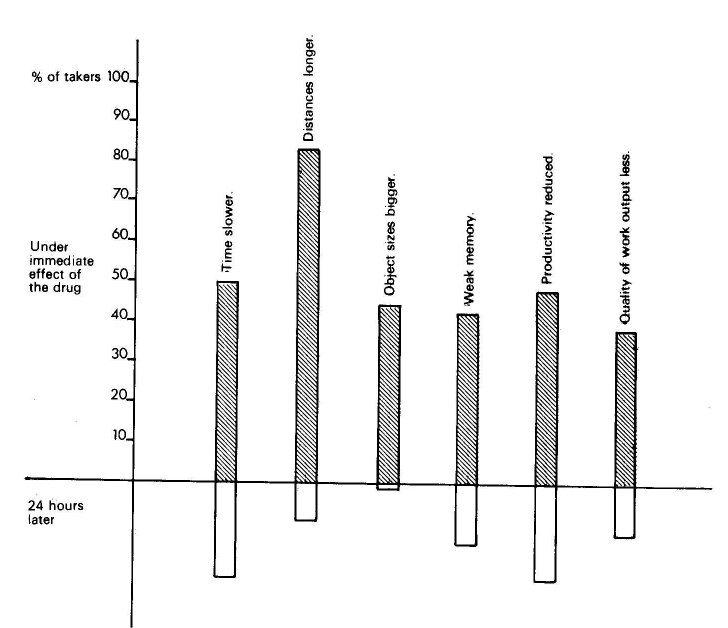

to 1962 administering a completely standardized interview (comprising about 400 items whose retake reliabilities were established) to 204 regular takers and 115 non-takers, we obtained a number of suggestive pieces of information. In Figure 2.1 we present a sample of this information about the subjective effects of hashish, immediately after smoking and 24 hours later.

A few points should be made clear here.

1. The users we interviewed for this pilot work were ordinary citizens. The average frequency they took the drug was 3 times a week, 1.08 gm. each time. Route of administration was usually smoking. When the kind of hashish they took was assayed for its THC content it was found to contain approximately 0.3 per cent by weight (Soueif, 1967).

2. Discrepancies in the same direction, though smaller in size, have been revealed on most of the items mentioned in Figure 2.1 when we interviewed about 350 chronic takers, who were all prison inmates, as part of our main study. This stability of the profile of findings emerged in spite of the fact that the latter group took the drug about 30 times a month.

The findings of the pilot study induced us to include among our tools of investigation, a number of objective psychological tests for the quantitative assessment of certain aspects of performance (Soueif, 1971). With the sampled background of exploratory information in mind, and being aware of the main aim of our project, viz, the study of the psychology of chronic cannabis consumption, the problem we were to tackle was, then, formulated as follows:

Fig.2.1. Under the immediate effect of cannabis and 24 hours later: subjective reports.

Are there significant differences between chronic takers and non-takers on the specified test variables?

In this paper my intention is to present part of our data on the performance of chronic cannabis takers on objective tests, compare such data with recently published information on analogous test performance displayed by subjects who were under the immediate effect of the drug, integrate both kinds of reports within a tentative theoretical framework and discuss extrapolations for future research.

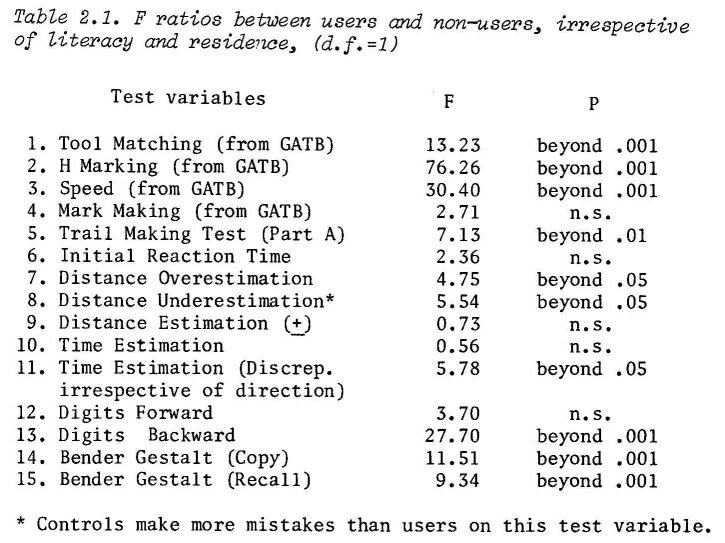

I We administered 16 test variables to 850 chronic takers and 839 non-takers. All were males ranging in age between 15 and slightly over 50 years. Our takers comprised the whole population of prison inmates that were exclusively convicted for cannabis use during the period from mid-1967 to about March 1968. Controls were selected from among inmates of the same prisons. The two groups were reasonably comparable regarding the relevant independent variables such as literacy, urbanism, socio-economic status and history of psychiatric complaint. Analysis of variance based on 3 x 3 x 2 factorial design was carried out, to supply 3 comparisons and 4 interactions for each test variable. Out of this complex matrix I am presenting in Table 1 F ratios between users and non-users irrespective of literacy and residence.

Chronic takers were definitely slow on simple psychomotor tasks as shown on tests 2,3 and 5. But when the speeded task required fine finger movements combined with change of orientation in the visual field, as was the case in test 4 (Mark Making) takers did not differ significantly from non-takers, though the latter still tended to show superiority. Again users were much below the average for controls on the Bender Gestalt (Lofvinger's method) which requires psychomotor activity scored for accuracy but not for speed.

Tests 1 and 6 involve speed of some psychic processes without appreciable motor involvement. Tool Matching measures speed of perceptual discrimination and it sorts out takers from non-takers at a high level of confidence. Initial Reaction Time requires speed of verbal reaction. This test failed to differentiate between the two groups though inspection of the cells showed that takers tended to react slowly compared with controls.

The remaining tests in Table 2.1 are rather cognitive. We found that cannabis takers tended to over-estimate moderate distances (a few centimeters), while non-takers tended to underestimate such distances. When we analysed the data regardless of direction of the error the two inclinations cancelled each other.

The result on time estimation was contrary to common expectation. Average time estimation for a period of 3 minutes (unoccupied by any overt behaviour) did not differentiate between users and non-users. When we analysed the differences between time as estimated by our subjects and geophysical time we found that the size of errors made by takers was smaller than that made by non-takers.

The Digits Forward, as a test for the span of immediate memory for numbers did not differentiate between users and controls. But the Bender Gestalt Recall which measures the subjects' span of memory for simple geometric designs discriminated between the two groups significantly.

The Digits Backward, which gauges the capacity for mentally holding and reorganizing a number of items marked a highly significant difference between users and non-users.

This is all about Table 2.1.

To summarize these findings in one comprehensive formula: The failures of chronic takers become more pronounced the more speeded motor activity combined with visual discrimination is required for the task they perform. It appears, on the basis of our observation, that within this paradigm the motor component is assigned more weight than the visual-perceptual.

II The question now is, how do these findings on the chronics compare with the rather corresponding results recently reported on the acute effects of the drug. In a series of experimental studies carried out and reported between 1968 and 1973 a number of findings were presented which make such comparison possible though conclusions should be drawn with due caution. The following sources of variability within this group of experiments, and between them on the one hand and our study on the other, set limitations to what we can make out of this comparison:

1. The wide differences between drug preparations utilized by various investigators (eg. marihuana; marihuana extract; synthetic THC).

2. The wide range of doses from one experiment to the other.

3. The different methods of administration (being sometimes given orally, and sometimes by smoking).

4. The rather narrow sector of the society to which subjects in most experiments belonged, being either students or graduates.

5. The fact that in some experiments subjects were drug-experienced while in others they were naive.

6. The setting, being always the secure but very arid lab environment.

Clark and Nakashima (1968) gave marijuana extract to a group of educated naive subjects, and used them as their own controls. Those investigators reported no consistent drug effect on the pursuit rotor. But they

found that both simple and complex hand and foot reaction times increased under drug effect. They, also, found that the magnitude of increment was positively dose related. Weil and colleagues (1968) gave marihuana to 9 naive university students to smoke. The subjects were also given placebo. The investigators report significant decrements in performance on the pursuit rotor when under marihuana. They also demonstrated a dose-response relationship. Hollister (1971) gave oral doses of synthetic THC to a group of subjects and found that they showed reduced accuracy on a drawing test which was rather difficult and with which the testees were not familiar. No slowing of performance was shown. Hollister, however, did not make it clear whether the task was explicitly speeded or not. Manno and associates (1970; 1971) reported that impairment on pursuit tracking performance would occur under the effect of cannabis smoking whether the smokers were naive or drug-experienced. When the drug was administered on a body weight basis a dose-dependent relationship could be demonstrated. Forney and collaboraters (1971) also demonstrated impaired performance on pursuit meter under drug effect. The Canadian Commission of Inquiry (1972) carried out a number of experiments in which they administered placebo, marihuana and synthetic THC to some 14 university students who were experienced with the drug. The Commission reported no effect of (smoked) cannabis on maximum tapping speed. The Commission's report mentions Bowman's work on Jamaican chronic heavy users pointing out that he found no evidence of significant psychomotor impairment. (1972, p.59).

So much for the assessment of psychomotor performance under the effect of cannabis. In summary, most of the work, that came to our knowledge, was confined to one main area, that of visual-motor coordination or accuracy of performance. Apart from the Commission's work on tapping speed and one or two investigations on simple and complex reaction time, speed of performance was seldom amply investigated. Yet this parameter has been repeatedly demonstrated by a whole series of clinicians to be significantly correlated with psychiatric disorder. Babcock (1930; 1933) first demonstrated that performance on error-free psychomotor speed tests-was abnormally impaired in schizophrenics (A. Yates 1973). Shapiro and associates (1955) concluded that psychiatric patients were slowest in tasks which did not involve problem solving and which emphasized speed in the instructions. A

few years later Payne and Hewelett (1960) confirmed those findings in a well designed large scale study (A. Yates, 1973). Indeed this part of the clinical literature, was among the sources that inspired us to enquire into the possibility of hashish takers showing any aspect of psychomotor retardation. Not that we imply that the mechanisms operating to bring out psychomotor slowness should be the same in cannabis users as well as in cooperative psychotics. Yet the research worker cannot and should not ignore some analogies. Moreover, the analogy we have adopted here is not in disharmony with Isbell's finding that 2THC can be psychotomimetic. (Nahas, 1973; p.171).

As to visual-motor coordination, the general trend of the above cited results was that impairment could be detected. This conclusion is in line with our findings on the Bender Gestalt (Copy).

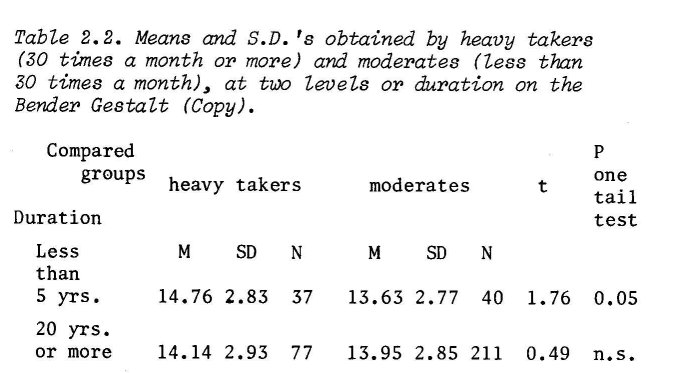

Another conclusion one may draw from the literature pertains to the positive dose-response relationship which could be demonstrated on tasks requiring hand-eye coordination. We investigated this point in a slanted way in our chronics. Two separate comparisons were made between users who took the drug less than 30 times a month and those who took it 30 times or more. The first comparison was carried out on those chronics who followed this schedule from one to five years. For a one tail test the difference was significant beyond .05 level showing moderates to be better on the Bender Gestalt Copy than heavy takers.

We made another totally independent comparison between those who took the drug at the above mentioned frequencies for more than 20 years. The difference, on the same test, at this level of chronicity, was almost nil. Table 2.2 shows the outcome of comparisons.

At face value one might conclude that the obliteration of the difference between the two latter groups was a function of the duration of drug use as such. The implication of such conclusion would then be in agreement with Weil and Colleagues' (1968) who reported that whereas naive subjects' performance on the Digit Symbol Substitution was impaired, chronics started with good baseline and improved slightly. We feel, however, that a more adequate explanation is, still, needed. It should take into account the following two facts:

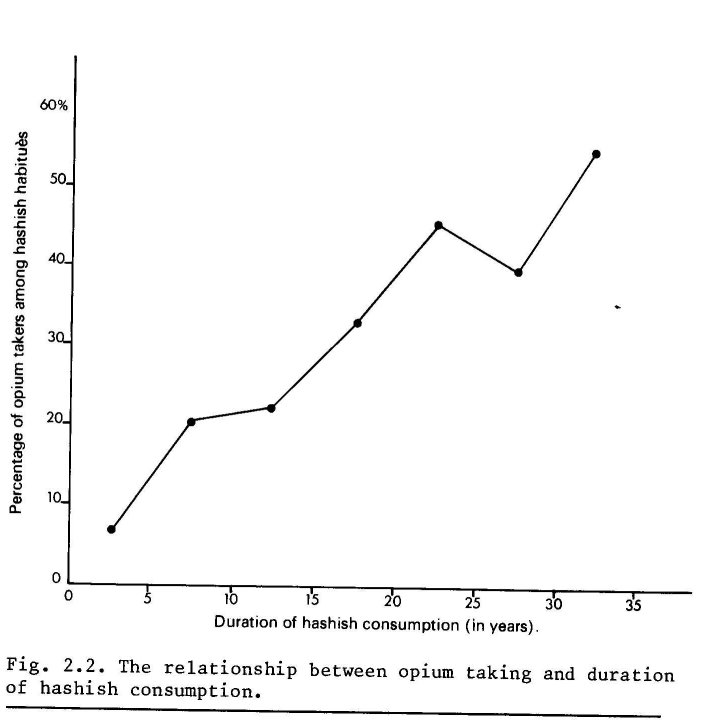

(a) Opium taking was found to be positively correlated with duration of hashish consumption. Figure 2.2 shows this relationship.

(b) It was also positively related to heavy cannabis use. (t = 2.16). (Soueif, 1971).

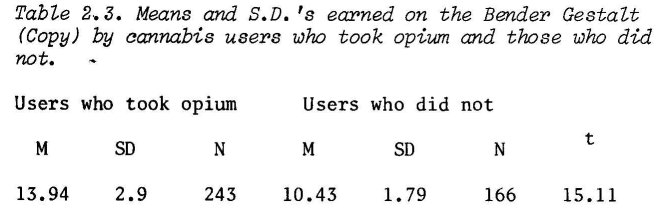

We have recently discovered that among users those who took opium over and above cannabis (14 = 243) obtained a much better score on the Bender Gestalt (Copy) than cannabis users who did not take opium. The difference was highly significant. gable 2.3).

This seems to shed light on the question why the dose-response relationship disappeared in our chronics when we moved from the 5-year group to the 20-year group.

It may be that, in the latter group, opium acts as an antidote to cannabis effects. Or it may be, basically, the question of who selects what as the drug or drugs of choice; namely that those who tend to take opium in addition to cannabis have an initially better stand on measures of accuracy of performance.

III We shall now consider the literature on the psychometric assessment of acute effects of cannabis on cognition.

Time estimation and short-term memory have been favoured as topics of research among investigators. But with distance estimation we could hardly find anything in

the experimental literature apart from a hint concerning the LaGuardia group of researchers. They reported that marihuana produced no significant changes in perception of length of lines on paper (Clark and Nakashima, 1968).

Weil and colleagues (1968) reported a tendency among naive subjects (N = 9) to overestimate a period of 5 minutes, when under the effect of smoked marihuana (containing 0.9 per cent THC by weight).

Tinklenberg and associates (1972) gave orally social doses of marihuana extract calibrated for THC content (0.35 mg./kg.) to 15 subjects who were all moderate cannabis takers. Placebo was also given within the framework of a double blind design. Time perception was guaged by the technique of time production. The investigators found that the drug induced under-production on this test compared with placebo. In another experiment by Hollister and Tinklenberg (1973) the same test was used. But this time there were no significant differences between time-production under marihuana and that under placebo.

Collating the results obtained by those three groups of researchers together with ours, no consistency could be detected.

A number of tests have been utilized to assess various aspects of immediate memory. Relevant among those tests are the Digits Forward and Backward and the Goal Directed Serial Alternation.

Melges and others (1970) and Waskow and collaborators (1970), both groups administered Digits Forward and Backward to volunteers under the immediate effect of the drug and of placebo, within the framework of a double blind design. They came out, however, with contradictory results. Melges' group demonstrated significant impairment for both functions. Waskow's group concluded that the drug had no significant effect on either.

With the Goal Directed Serial Alternation we were not in a better position.

Melges and his group (1970) reported progressive impairment of performance with increased doses of THC. But Tinklenberg and co-workers (1972) and Hollister and Tinklenberg (1973) reported no significant deterioration of function under drug effect. Tinklenberg and associates (1972) added another test labeled Running Memory Span, a variation of the Digits Forward. This test, again, did not reveal any significant effect of the drug.

Obviously, good experimental research has been invested in the area of time perception and short term memory. But the results, taken at face value, cannot be meaningfully integrated together, nor can they be reconciled with our corresponding findings on the chronics. However, initial individual differences on related functions can be utilized here. I propose the following as a working hypothesis: The amount of deterioration that is likely to be effected by the drug is a /Unction of the general level of predrug performance: other conditions being equal, the lower the initial level the less deterioration. It is probably the general case behind what Dr Tinklenberg and his colleagues called the initial level of proficiency on the tested variable (1972).

You might well recall that Waskow and co-workers studied a group of criminal offenders whose average I.Q. was 95. They got no significant impairment on Digits Forward nor on Digits Backward (1970). Contrasted with that was Melges and his colleagues who worked on a group of graduate students and got significant results (1970). Relevant here is the fact that the Digits Span test correlated up to 0.51 with the total score on the Wechsler (Wechsler, 1954, p.85).

According to the same working hypothesis, conflicting results concerning the Goal Directed Serial Alternation Test could also be resolved (rinklenberg et al., 1972).

The same idea may shed light on some of the negative results obtained by Bowman on cannabis takers among Jamaican natives (Commission's Report 1972, p.56). Possibly those natives were initially of low level of proficiency.

It is interesting to note that the same idea was mentioned, though en passant, by R.W. Payne in a totally different context. Reviewing the work, done in the sixties, on intellectual deterioration under conditions of mental illness Payne found that he was confronted with two groups of studies: Group A, which ended up with 'patients who had originally above average or average I.Q. and showed significant deterioration, and Group B, concentrating on patients who were initially subnormal and displayed very little deterioration. He drew the following conclusion: 'It is possible to speculate that the dull who had become psychotic deteriorate little intellectually'. (Payne, 1973).

Indeed this same paradigm could impose form and meaning on a sizeable amount of data we collected on our takers. The following two sets of derived hypotheses, each comprising two mutually complementary predictions, were formulated:

Set A:

Prediction 1: We would expect performance on simple psychomotor and cognitive tests to correlate significantly with literacy (up to a certain level). If this was the case, Prediction would then be: The lower the level of literacy, the smaller the size of impairment associated with drug taking.

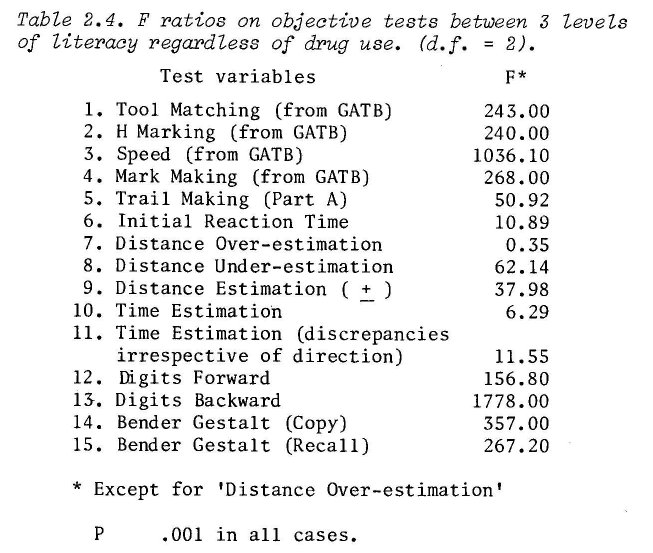

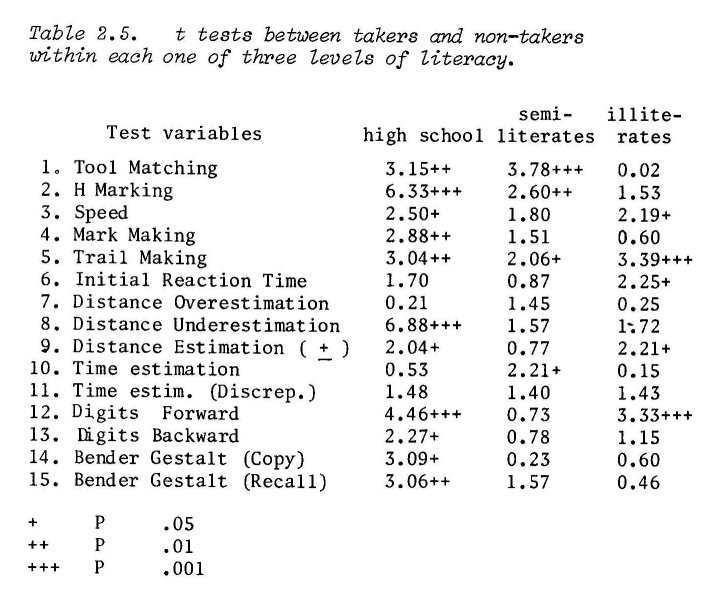

That the two predictions were in fact borne out can be readily seen in Tables 2.4 and 2.5. Table 2.4 shows the outcome of analysis of variance for the data on the same tests mentioned before; this time between 3 levels of literacy irrespective of drug use.

Except for 'Distance over-estimation' F r atios were invariably very highly significant.

Table 2.5 presents 3 columns of t values. Each column shows the outcome of comparison between means (or medians) earned by takers and controls within each of 3 levels of the literacy-illiteracy continuum.

Set B:

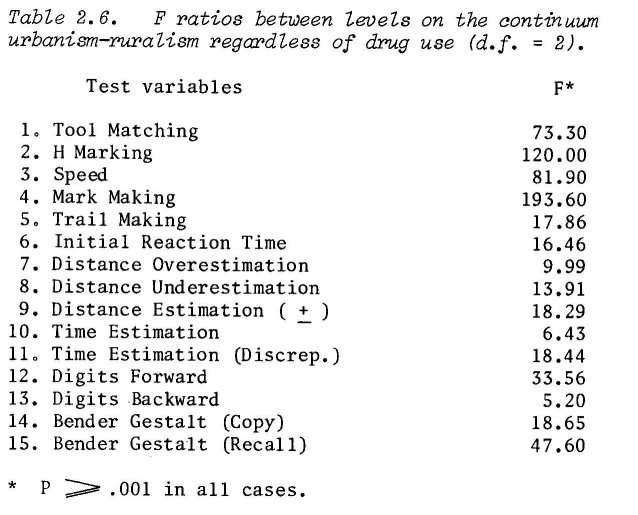

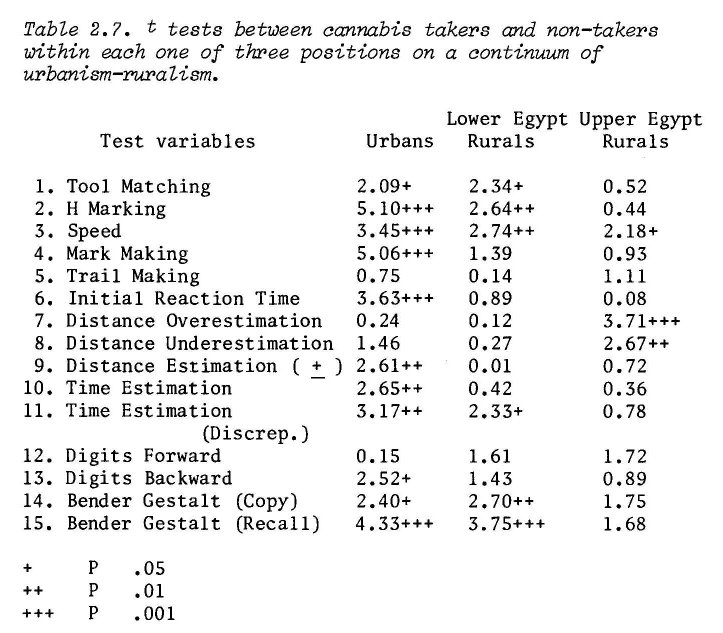

This was analogous to set A except for the fact that it hinged upon the parameter of urbanism-ruralism instead of literacy.

Prediction 1: We would expect performance on simple psychomotor and cognitive tests to be significantly related to urbanism. In this case,

Prediction 2 would be: The less urbanized cannabis takers were, the smaller the degree of impairment correlated with drug taking.

These two predictions were also confirmed, as can be seen in Tables 2.6 and 2.7.

By and large, our hypotheses were confirmed. Other predictions may also be worked out to amplify our basic formula. For example, we would expect the same pattern of findings to emerge in the area of creative thinking abilities. This means that, contrary to common belief, the highly creative per ns would show more impairment than the mediocre under drug effect. Research in creativity has been making tremendous progress during the last 20 years. To test this prediction the research worker can find available a bit number of good tools for the measurement of factorially purified relevant parameters such as originality, flexibility, ideational fluency and maintaining direction (Soueif and S. Farag 1971; Freeman et al. 1971).

Another example still, concerns the difference between age groups. We would expect young cannabis takers (-25 yrs.) to be more seriously affected than older age groups (40+). Relevant data is in the process of analysis.

The implications of this theory for any policy making, concerning prevention, education, legislation or direction of future research are quite obvious. The main point would always be the fact that, citizens who lie within the higher brackets of ability (in the broadest sense of the word) are likely to get the greater damage, when exposed to the effects of cannabis use.

The question now is: Where do we go from here?

At face value the present state of information concerning the behavioural effects of cannabis consumption suffers from two serious difficulties: gaps and conflicting results. To overcome the consequences of such a situation we may have to choose between two alternatives marking the two opposite poles of a continuum: empiricism or rationalism. An empirically oriented approach would aim at symptomatic treatment of the situation and would suggest simultaneously adopting two lines of action:

1. Filling in the gaps: For example: in spite of the fact that epidemiological reports make it clear that about one third of cannabis takers in some Western countries were females we had almost no information on behavioural sex differences under cannabis. This area, therefore, should be covered. Another area would be speed of psychomotor performance. A third would be speed of intellectual processes. A fourth would be the capacity for distance estimation. A fifth size estimation. A sixth creative thinking ... etc. One could go on counting a number of such relevant areas.

2. Resolving sources of conflict in research findings: One would recommend increasing the number of subjects tested in the various experiments in order to permit individual differences to play their role fully. Or, one would recommend explicitly stating the initial scores of the subjects on specified variables without the investigator being bothered by the question of the size of N.

Such an empirically oriented approach, however, will suffer from the shortcomings of any post-hoc framework, no matter how finely its details were worked out. It will always remain remedial, but not preventive; always an after-thought, never a guiding insight.

The need for a more rational approach, therefore, seems compelling. In preparing a rational plan of work, field and lab studies accomplished so far, may be viewed as explorations, suggesting an adequate scheme for a well integrated study of the problem. It would be advisable to give optimum chance at the initial stage of developing such a scheme, to all relevant questions to be raised, by simply enumerating all points already investigated, suggested for further research or mentioned by way of speculation. A conference or a circular letter of enquiry for the brainstorming around this inventory of problems should follow. We should then try to obtain a more or less comprehensive list of queries including instructive hints on priorities. If priority is given to a selected group of items (research and application-wise), a well balanced programme for a broad attack on the problem in its genuine complexities can then be considered.

Three main requirements, at least, are necessary in such a programme: (a) it should make use of standardized and calibrated tools for the assessment of drug effects, (b) it should allow for the systematic study of significant individual differences, (c) it should permit transnational and transcultural integration of findings.

When we select tools for the objective study of drug effect, they should be representative of a whole universe of tests or scales for the assessment of a certain function (or group of intercorrelated functions). When objective assessment is mentioned, there is always the hazard of research-workers becoming test-minded rather than function-minded. The trouble with some tests is that they have rather narrow common variance. A sensible rule in factor analysis is never to identify a factor by less than three variables. It may add to the accuracy and meaningfulness of our work to start by explicitly defining what functions to measure, then select and/or devise more than one test variable to use for the measurement of each function.

Individual differences, with their multiplicity and diversity, have always been among the main sources of variance in the experimental study of human behaviour. Nevertheless, the systematic handling of this variate is still far from attaining the status of an essential ingredient in the design of experiments on human behaviour. An adequate formula has to be worked out to help future researchers select the right dimensions

that would act as good intervening variables to impose optimum regularity on whatever dependent variables are considered for investigation. Sources of inspiration to serve this purpose may be clinical psychiatric chapters dealing with premorbid personality and with indicators of prognostic value. A useful rule is to consider promising intervening variables those dimensions which have been demonstrated (usually in other areas of research) or thought on explicitly stated grounds, to correlate with the variables under study.

It would serve our purpose in the long run, to include, among our tools of investigation a minimum of tests that would be 'fair' to a wide variety of cultures. The academic problem of whether there are tests which

can really be 'culture-fair' should not disturb us much. What we actually need is to use a number of test variables that can with minimum modification be administered to members of various cultural groups. The research worker should always be able to distinguish between two aspects of human behaviour: action and significance, or the overt and the covert components. The field of attitude research teaches us a good lesson about how intricate the relationship between these two ingredients is. Briefly stated, they should be treated as two separate variates, which sometimes, but not always, are intercorrelated (Dillehay 1973). Speed of psychomotor performance, proficiency of immediate memory, accuracy of fine movements ... etc.; those are demonstrable parameters of overt behaviour which can and should be investigated in their own right. The meaning of the testing situation to an average English= man might differ from what it looks like to an average Egyptian, but that would not negate the fact that relative inaccuracy of fine movements could be shown in both English and Egyptian takers. Such solid facts should be recorded on the widest possible scale without waiting for the problem of the covert component to be solved.

It seems quite feasible and indeed should prove rewarding to plan straight away for comparative studies based on the systematic variation of total cultures (or well defined cultural parameters) together with degrees of permissiveness towards the drug. We may need to remind ourselves, all through this kind of work, of the following statement made by Cluckhohn 20 years ago: 'It is true., that for roughly half a century now, anthropologists have concentrated preponderantly upon.. culturally relative behaviors. Nevertheless, there has been more effort at stating and testing universal hypotheses than many psychologists recognize.' (C. Kluckhohn, 1954). True, correction terms will, in all probability, be needed. The safest way to secure such terms is usually to present users' scores in the light of norms for local controls. Meaningful comparisons across national or cultural boundaries can, then, be made in terms of some kind of standard scores. This procedure, however, cannot be a guarantee against the absurdities of unwarranted conclusions. A measure of caution on the part of the investigator is always indispensable.

We must remember that cannabis dependence is the end result of an international activity with many forms of clandestine cooperation to perpetuate the phenomenon. Granting that our scientific efforts in this field are, ultimately, steered towards utilitarian targets, they should be run on an equally broad basis of international collaboration to attain comparable efficiency. True, we are, in a sense, working here on such lines. Our collaboration at the moment, however, takes the form of discussing work already accomplished and some extrapolations therefrom. Something more drastic is needed. We should start designing and carrying out an international project that requires transnational division of labour. How to operate this in actual fact? Probably, the correct approach would be to allow, right from the beginning, for more than one solution to meet this demand. The real challenge is to keep flexible, by drawing up a repertoire of alternative solutions, but never losing direction to the main target.

Cannabis consumption is endemic in one part of the world; there, we can find a wealth of data just waiting to be collected and processed. Apart from cultural differences as filtered into personality, those chronics presumably represent the clinical picture of the user we may have to deal with, in the very near future, in other parts of the world where chronicity is just emerging.

REFERENCES

Babcock, H. and Levy, L. Manual of Directions for the Revised Examination of the Measurement of Efficiency of Mental Rinctioning. Chicago: Stoeling.

Clark, L.D. and Nakashima, E.N. Experimental studies of marihuana, Amer. J. Psychiat., 1968, 125/3, 379-384. Commission of inquiry into the non-medical use of drugs: Cannabis, Ottawa, 1972.

Dillehay, R.C. On the irrelevance of the classical negative evidence concerning the effect of attitudes on behavior, Amer. Psychologist, 1973, 28/10, 887-891.

Forney, R.B. Toxicology of marihuana, PharmacoZ. Rev., 1971, 23, 279-284.

Freeman, J., Butcher, H.J. and Christie, T. Creativity: A selective review of research, London: Society for Research into Higher Education, 1971.

Hollister, L.E. Marihuana in man: Three years later, Science, 1971, 172, 21-28.

Hollister, L.E. and Tinklenberg, J.R. Subchronic oral doses of marihuana extract, Psychopharmacologia, 1973, 29, 247-252 (memeographed).

Kluckhohn, C. Culture and behavior, Handbook of social psychology, G. Lindzey ed., Cambridge, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, 1954, 921-976.

Manno, J.E., Kiplinger, G.F., Haine, S.E., Bennett, I.F. and Forney, R.B. Comparative effects of smoking marihuana or placebo on human motor and mental performance, Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 1970, 11/6, 808-815.

Manno, J.E., Kiplinger, G.F., Scholz, N. and Forney, R.B. The influence of alcohol and marihuana on motor and mental performance, Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 1971, 12/2, 202-211.

Melges, F.T., Tinklenberg, J.R., Hollister, L.E. and Gillespie, H.K. Marihuana and temporal disintegration, Science, 1970, 168, 1118-1120.

Nahas, G.G. Marihuana, deceptive weed, New York: Raven, 1973.

Payne, R.W. Cognitive abnormalities, Handbook of abnormal psychology, H.J. Eysenck ed., London: Pitman Med., 1973, 420-483.

Payne, R.W. and Hewlett, J.H.G. Thought disorder in psychotic patients. Experiments in personality, vol. II, Psychodiagnostics and psychodynamics, H.J. Eysenck, ed., London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1960, 3-104.

Shapiro, MB., Kessell, R. and Maxwell, A.E. Speed and quality of psychomotor performance in psychiatric patients (Memeographed copy, 1955).

Soueif, M.I. Hashish consumption in Egypt, with special reference to psychosocial aspects, Bulletin on Narcotics, 1967, 19/2, 1-12.

Soueif, M.I. The use of cannabis in Egypt: A behavioral study, Bulletin on Narcotics, 1971, 23/4, 17-28.

Soueif, M.I. The social psychology of cannabis consumption: myth, mystery and fact, Bulletin on Narcotics, 1972, 24/2, 1-10.

Soueif, M.I. and Farag, S.E. Creative thinking aptitudes in schizophrenics: A factorial study, Sciences de l'Art — Scientific Aesthetics, 1971, 8/1, 51-60.

Tinklenberg, J.R., Kopell, B.S., Melges, F.T. and Hollister, L.E. Marihuana and Alcohol, Arch. Gen. Psychiat., 1972, 27, 812-815.

Waskow, I .E., Olsson, J.E., Salzman, C., Katz, M.M. and Chase, C. Psychological effects of tetrahydrocannabinol, Arch. Gen. Psychiat., 1970, 22, 97-107.

Wechsler, D. The measurement of adult intelligence, Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins, 1944.

Weil, A.T., Zinberg, N.E. and Nelsen, J.M. Clinical and psychological effects of marihuana in man, Science, 1968, 162, 1234-1242.

Yates, A.J. Abnormalities of Psychomotor Functions, Handbook of abnormal psychology, H.J. Eysenck, ed., London: Pitman Med., 1973, 261-283.

DISCUSSION

Professor Soueif's paper excited considerable interest and discussion, mostly on methodological considerations.

Dependence

Dr Soueif was asked about his use of the term 'cannabis dependence', and explained that he was adopting a WHO convention in using the term. The user group in his study were operationally defined by their conviction for a cannabis offence. For him cannabis dependence was synonymous with extended periods of cannabis use: in spite of the constraints against use and the threat to the organism, many people did use cannabis for extended periods, and many reported that they could not stop.

ACUTE VERSUS CHRONIC EFFECTS

Dr Edwards stressed the distinction between effects of intoxication, and long-term effects of previous use: 'It is important with many sedative-type drugs to ensure that a sufficiently long time period occurs between

cessation of use and testing. Do you have any information about this time interval in your study?'

Professor Soueif explained that 'we were pretty sure that some of those prisoners didn't stop taking cannabis while they were in prison. So they might have been using cannabis the day before they were tested.'

GENERALISABILITY OF RESULTS

Mr Hasleton pointed out that 'if one takes groups in prison, then one is not taking a sample from which one can generalise to other samples other than other groups in prison. So if prisoners who have used cannabis differ in various ways from prisoners who have not, it does not necessarily follow that non-prisoners who have and have not used cannabis will differ from one another in the same ways.'

Professor Soueif stated that he was not attempting to generalise to other populations.

MAGNITUDE OF OBSERVED SCORE DIFFERENCES

Several participants were concerned to know the magnitude of the differences between the test scores of users and non-users. Dr Smart remarked "I don't get any feeling from your paper or your remarks of the size of difference you are talking about. In two of the tables the differences that come out significant are really quite tiny. When we're talking about the social policy-implications of the differences, I think that we should know their magnitude.'

In response to this and other similar questions about size of differences, Professor Soueif suggested that differences were always a function of the test used, that the means and standard deviations had been published (Bull. Narc. XXIII, 4, 1971), that he did not think it would be appropriate to present detailed data to a large seminar group, and that even small differences were important. Later tests could be developed to find bigger differences, 'the point I am trying to make is that there are significant differences. Are we ready to ignore that?'

QUESTION OF EQUIVALENCE OF GROUPS: MATCHING

Dr Miller: 'The real significance of these differences, whatever their sizes, depends on how closely you were able to match the experimental and control groups. I wonder if you could give us a list of the specific operational variables on which they were matched and tell us whether or not you ran the same kinds of statistical tests on those matching variables between the two groups.'

Professor Soueif: 'What can I say, globally, is that they were similar on a number of variables, and there were also some dissimilarities.'

Dr Miller asked if Professor Soueif had tried to correlate the group differences in matching variables with the test score differences, and Professor Soueif said that they were looking again at the data and

might do this.

SAMPLE SIZE AND MEANING OF STATISTICAL SIGNIFICANCE

Dr Miller suggested that statistical significance, with sample sizes of about 800, must be interpreted with caution, especially bearing in mind the fact that the samples were not exactly equivalent in terms of matching variables. He suggested that two groups of only one hundred subjects might be taken, well matched on a variety of variables, and that the differences in test score between these groups be looked at.

In conclusion, it is fair to say that some of the participants felt that insufficient data had been presented to justify full acceptance of the conclusions drawn.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|