Chapter 13 Monitoring cannabis availability in Europe: issues, trends and challenges

| Manuals - Cannabis Reader |

Drug Abuse

Keywords: availability — cannabis — market — prices — supply

Setting the context

In most of Europe, few would argue that cannabis is difficult to obtain for those who seek to use it. Nonetheless, when looking at issues of supply and demand, sellers and buyers, products and distribution, there are numerous pieces of the picture which need to be assembled to gain an insight into how policymakers may tackle the drug's distribution. This chapter looks at the broader concept of availability of cannabis, a concept that goes beyond market analysis and embraces further issues such as price and the perceived ease of purchasing a drug.

Cannabis is the most frequently used illicit drug in the EU. Some commentators have suggested that the drug has become more readily available, yet the concept of availability is one that is both difficult to define and to measure. Nonetheless, it is possible to look at a number of indirect indicators that, when taken together, allow for the construction of a more general picture of cannabis availability in Europe.

In this chapter, data on drug seizures, prices, potencies and perceived availability among the general public are used to explore overall trends in the availability of cannabis products in Europe between 1 998 and 2003. Analysis is presented for EU Member States and Norway.

Data analysis at this level is always challenging and a range of methodological issues and data limitations means that conclusions must be drawn with caution. In particular, the amount of missing data on some measures presents a serious problem for analysis. Despite these difficulties some clear trends do seem evident in some of the indicators. However, when taken together no coherent picture emerges, with some datasets supporting the assumption that cannabis availability has been increasing whilst other information suggests a more stable situation.

Further reading

Cyclical sources of data on drug supply

EMCDDA, Annual reports and Statistical bulletin, European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, Lisbon (published annually in November).

UNODC, World drugs reports and Interactive seizure reports, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Vienna.

World Customs Organisation, Customs and drugs reports (published annually in June).

General reading

Gouvis Roman, C., Ahn-Redding, Simon, R. (2007), Illicit drug policies, trafficking, and use the world over, Lexington Books, Lanham.

UNODC (1987), Recommended Methods for Testing Cannabis, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Vienna.

Monitoring cannabis availability in Europe: issues, trends and challenges

Chloé Carpentier, Meredith Meacham and Paul Griffiths

Towards a conceptual framework for exploring drug availability — approaches and data sources

The availability of illicit drugs is an important concept for drug policy, and reducing availability can be found as an explicit policy objective at both European and national levels (').

Rationale

Policy interest in drug availability can be broadly characterised as focusing on two topics. The first topic is the relationship between availability and demand and rests upon an implicit assumption that changes in the availability of drugs will be associated in some way with levels of use. At EU level this has resulted in a fairly pragmatic

monitoring strategy of collecting and analysing information that may allow changes over time in drug availability to be charted. Currently, as described below, EMCDDA activities in this area focus on improving the reliability and comparability of data sources to allow better monitoring of trends in availability at street level for the more prominent groups

of drugs.

The second topic of interest is to understand what factors can have an impact on the availability of different drugs, in order to inform the development of interventions with the aim of addressing these factors. Answering this sort of question goes beyond simply monitoring and requires more complicated research or statistical modelling exercises.

Defining 'availability'

From an operational perspective it is clear that defining availability is not simple: the word has been interpreted differently in different contexts. In a general sense, availability might be treated as synonymous with 'access', and in the drugs field the concept has sometimes been simply associated with 'drug supply data'. For example, one report from the USA on cocaine availability produced various estimates based on a model derived principally from production and interdiction data (ONDCP, 2002).

Data from demand-side indicators have also been used to estimate drug availability, most simply in questionnaires that ask respondents to rate, in some way, the availability of drugs in their locality. Additionally, data on drug consumption or offers of drugs have also been used as indirect indicators. Currently, the developing consensus supports a conceptual framework for assessing drug availability that includes both supply and demand elements, though these elements have been made operational in a variety of ways and no common approach currently prevails.

Nonetheless, it does appear reasonable to consider drug availability as consisting of a synthesis of the following elements:

• the amount of illicit drugs physically on the market (drugs produced and trafficked but not seized — drug supply to the market);

• the structure of drug flows and distribution (retail outlets, dealers, drug scenes); and

• the relationships between drug users/non-drug users and this distribution structure (access).

A further valuable analytical distinction is between global availability and street level availability. In the context of the EU, global availability might be defined as drug availability at the upper/wholesale level of the market, or at the trafficker's level, as a result of the interaction between drug supply and drug control strategies at that level of the market. Street level availability might be defined as drug availability at the retail level of the market, or at the user's level, as a result of the interaction of global availability, distribution processes and strategies, drug control strategies at retail market level and access of various groups of users/non-users to different illicit products. Except for data relating to seizures, a common link between global and street level availability, this paper will focus on the street level of availability.

Current indicators

The current EMCDDA approach has been to develop a set of indicators of drug availability, with particular focus on street level availability. As drug availability is an ill-defined concept, a multi-indicator approach has been adopted with the objective of bringing together these different data sources into a more general measure of availability. Information is provided annually through the Reitox network of national focal points and covers areas including: drug prices at retail level, contents of drugs and potency, drug seizures and the perceived availability of drugs at street level.

Clearly, none of these information sources produce a simple or unproblematic reflection of the availability of drugs in Europe and any analysis must be made with caution. The corroboration of contextual and qualitative information is particularly important if erroneous inferences are to be avoided. Drug seizures, for example, are influenced by the level and efficiency of law enforcement activity (which vary both between and within countries over time) as well as the availability of drugs in a particular market. Despite this problem, seizure data do appear to be useful in looking at trafficking routes (UNODC, 2005) and in many cases it seems fair to make the assumption that drug seizures in a given country are at least somewhat correlated to the amount of drugs imported or smuggled into that country. It has even been assumed in international discourse that drug seizures represent a relatively stable proportion of the drug supply (often assumed to be about 10%) and could therefore be considered as an indicator of drug availability on the national market. In the case of cannabis, seizures of plants have also been taken as an indicator of the extent of domestic cannabis cultivation or cultivation in neighbouring countries (Pietschmann, this monograph).

Similarly, both price and the potency of illicit drugs may have an impact on the perceived availability of illicit drugs and reflect important supply-side factors that affect access. This relationship is often not a simple one, but both price and potency can be considered as indirect indicators of drug availability. Drug prices may vary according to many factors including the level of the market or volume at which they are traded. Prices are also likely to reflect the basic laws of supply and demand. In this respect, lower prices would in theory seem to indicate a higher availability (or a greater supply), or, although it is perhaps less likely, reduced demand.

For a number of methodological and practical reasons, interpreting data on potency is a complicated task — and these difficulties are particularly apparent for cannabis (see below). However, this information is collected in some EU countries principally as a legal requirement for criminal prosecutions, but also, in some cases, as part of drug monitoring activities. Although establishing a direct link between potency and availability is difficult, changes in the overall potency of drugs, especially when prices are moving in an opposing direction, can be regarded as a useful indirect indicator of availability — albeit one to be interpreted carefully.

Finally, school and adult surveys sometimes include questions on the perceived availability of drugs in the communities from which the respondents are drawn. Although important methodological questions exist, such as the influence on such perceptions of different kinds of exposure to drug use and the overall reliability of perceptions reported in drug surveys, this kind of data can also provide indirect yet complementary data on drug availability.

What do the available data tell us about cannabis availability in Europe?

Due to methodological issues and a simple absence of complete and detailed time-series data, limitations are imposed on any attempt to answer this question. Despite this setback, it is possible to some extent to construct a general picture of the different indicators of cannabis availability in Europe. Taking the year 2003 as an example, below we describe the information available and explore to what extent a coherent picture of trends in cannabis availability can be established.

Seizures

The EMCDDA dataset on drug seizures dates back to 1985, and the data records both seizures and quantities of drugs seized. Data availability has varied as countries have improved their reporting capacity, but considerable work remains to be done on improving the comparability of measures used. These data relate to all seizures made over the course of a year by all law enforcement agencies (police, customs, national guard, etc.). Although generally rare, double-counting may occur within the data presented by some countries.

The implications of looking at quantities seized or numbers of seizures can be different. A major proportion of the number of overall seizures usually comprises small seizures made at the retail or street level of the market. Quantities seized may fluctuate from one year to another due to a few exceptionally large seizures of drugs made further up the distribution chain. For this reason the number of seizures is sometimes considered

a better indicator of trends — although a count of the number of seizures is sometimes less available. A further complication for cannabis arises because of the different types of cannabis available in Europe. Only since 1995 has it been possible to begin to make a distinction between different types of cannabis products — that is, plants, herb and resin — and some countries are not able to do this. Therefore, the corresponding time series are sometimes incomplete, making the analysis of EU trends more difficult (9.

Seizures of cannabis plants

Cannabis grown within the EU is beginning to represent a significant part of the market. Data on seizures of cannabis plants from EU reporting countries and Norway in 2003 amounted to 8 600 (3) seizures of about 1.6 million plants and 8.9 tonnes of the same material. The highest numbers of seizures were reported by the United Kingdom, followed by Hungary and Finland (4), while the largest quantities were recovered in the Netherlands, followed by Italy, Poland and the United Kingdom.

Not all countries can provide data for the period 1998-2003 but based upon the information available a decline was evident in the number of seizures of plants reported until 2001, followed by a subsequent increase. Since 1998, overall quantities seized have been increasing with peaks in 2000 and 2001, mainly due to exceptionally large seizures made by Italy in these years (1.3 and 3.2 million plants, respectively).

Seizures of cannabis resin

About 200 000 seizures (5) and 1 025 tonnes of cannabis resin seized were reported in the EU and Norway in 2003, with Spain accounting for the biggest share by far, both in terms of numbers and quantities seized, and reflecting the importance of the Iberian peninsula as an importation route for Moroccan-produced cannabis entering Europe (see Gamella et al., this monograph). France and the United Kingdom, which represent relatively large markets for cannabis, also stand out as countries seizing significant quantities of the drug. Both in terms of numbers and quantities, overall cannabis resin seizures increased during the period 1998-2003. However, in 2003, the number of seizures declined while quantities increased highly due to large amounts recovered in Spain.

Seizures of herbal cannabis

In the EU herbal cannabis is less commonly seized than resin — illustrated by the fact that in 2003 the total amount of herbal cannabis seized was 79 tonnes, or less than 10% of the amount of resin seized, with the United Kingdom recovering the largest quantities every year, followed by Italy. Numbers of seizures of herbal cannabis have been increasing overall since 1998, though they remained stable in 20031 as opposed to figures for quantities seized, which have been declining for most years.

In analysing seizure data a useful distinction can be made between police and customs seizures, based on the assumption that police seizures may better reflect retail level activity and that customs seizures are at a wholesale level and may include drugs in transit to third countries. Since 1995, data collection at the European level have included a request for a breakdown by seizing entity. This dataset requires further development as not all countries are currently able to provide this information nor is it possible at present for some countries to make a distinction between different cannabis products. Therefore, due to missing data, totals will represent an underestimate of the true situation.

Despite these limitations, data show that from 1 998 to 2003 there was a general increase in the number of police seizures of cannabis (all material included) whilst the number of reported customs seizures remained relatively stable. Quantities of cannabis seized by both police and customs authorities increased during this period at about the same rate. For both seizing entities Spain was responsible for a major share of the quantity of drugs recovered. A gross calculation of the average sizes of cannabis seizures (6) over the period 1998-2003 shows that police seizures are usually smaller than customs ones, with size ratios up to 1:100 in Spain and the United Kingdom.

Retail prices

Data on retail prices of cannabis products come from a range of different sources, the comparability of which is often unclear. These sources include test purchases, interviews with arrested dealers/consumers, police intelligence and surveys of drug users. Sampling strategies used for calculating price estimates also vary considerably and in some countries the representativeness of these data is questionable. The EMCDDA is working with national experts to improve the comparability of data and methodological approaches of collecting price data at the street or retail levels. Although caution is required when drawing any firm conclusions from the currently available dataset, it is possible to obtain a general picture of overall trends.

Because prices vary by product type, efforts have been made to distinguish between different types of cannabis. The main breakdown by product type is made between herbal cannabis and cannabis resin. Whenever possible, a further distinction is made between different types of herbal cannabis, as the herbal cannabis market often contains a number of distinct products. In particular, high potency types of cannabis, such as some forms of domestically produced product, attract a premium price. However, it has only recently become possible to make this sort of distinction, and further analysis is hampered by a lack of data on the dynamics of the European cannabis market.

Prices in 2003

Data for 2003 on the price of resin and herbal cannabis are available from 24 and 21 European countries respectively. The ranges reported for minimum and maximum prices of cannabis resin and herb are relatively narrow compared with potency data (see below). Although considerable variation is seen between the cheapest and most expensive countries, considerable overlap also exists between many countries with respect to average prices reported. The average price of resin varied from EUR 1.4/g in Spain to EUR 21.5 in Norway, with about half of all countries reporting average prices in the range of EUR 5-11. Most countries reported a lower price for herbal cannabis than resin, again with a considerable range of EUR 1.1/g in Spain to EUR 12 in Latvia, and most countries reporting average prices between EUR 5 and 8 per g. The importance of looking at sub-types of herbal cannabis was illustrated by the Netherlands and the United Kingdom, where analysts were able to provide a separate estimate for home-produced cannabis, the price of which was higher — on average EUR 61g in the Netherlands and EUR 8.2/g in the United Kingdom.

Because cannabis prices may be higher in countries where other goods are more expensive or there is a higher standard of living, in order to attempt to explain differences in cannabis prices between countries, it is possible to look at correlations between a country's average prices of cannabis products and the country's demographic and socio-economic situation in the same year, as represented by two indices — the human development index (HDI) (7) and gross domestic product per capita in purchasing power parity (GDP per capita in PPS) (8). Analyses show that there is no clear correlation between such indicators and cannabis prices (by product) when considering all the reporting countries together. However, further distinction between groups of countries suggests that prices of both resin and herbal cannabis are positively correlated to both the HDI and GDP (per capita in PPS) in the countries from the EU-15 (9). In the new EU Member States, there is either a negative or non-existent correlation between prices of both cannabis products and the HDI and GDP (per capita in PPS). However, it should be noted that the negative correlations found in this group of countries were stronger for herbal cannabis than for resin (10).

Though this analysis is tentative, it does suggest some relationship between cannabis prices and national demographic and socio-economic situations in the older EU Member States, where cannabis markets are relatively long established. The picture is less clear for the new Member States, where there are not only questions of data quality but also the possibility that markets in these countries are subject to strong change. Other indicators have suggested that cannabis use is increasing, though often from low initial levels, and that these cannabis markets should be considered relatively 'young' and far less established. Routes of cannabis trafficking might also explain some of the differences observed between EU countries in the retail level price of cannabis products — particularly by noting the proximity of Morocco for producing cannabis resin and the increasing importance of Albania for producing herbal cannabis. Countries that are closer to these producing regions are likely to experience lower transport costs during trafficking and, therefore, lower prices.

Long-term price trends

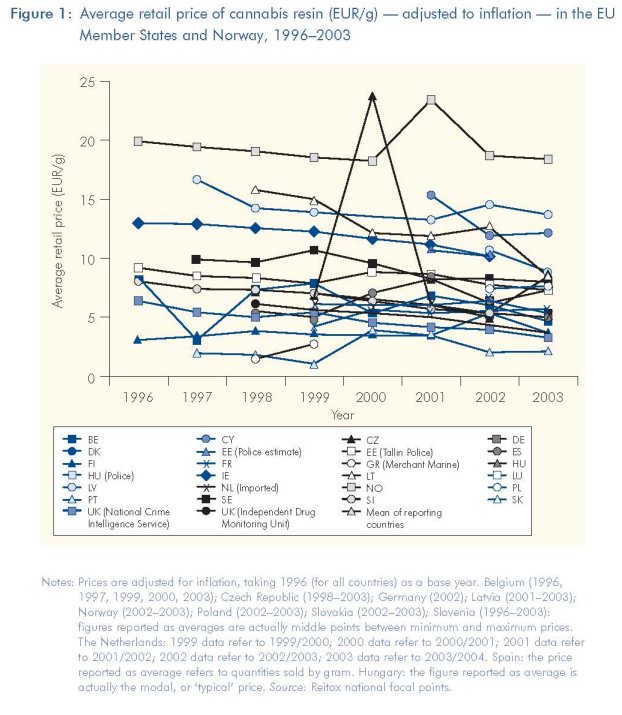

An analysis of long-term trends in prices is hampered by the fact that although a few countries have been reporting data on cannabis products since the mid-1990s or earlier, it takes several years for the dataset to grow sufficiently large enough to explore trends at a European level. It should also be noted that data from the new EU Member States have only been available since 2002. The EU mean (arithmetic mean) of average prices of cannabis resin (corrected for inflation (")) in reporting countries slowly decreased in the period 1996-2003 (see Figure 1). A more detailed analysis of such prices in countries that have been reporting for four years or more shows that overall trends for 1999-2003 (9 were either stable or declining in all countries, with the exception of France and Luxembourg, where a modest increase was noted.

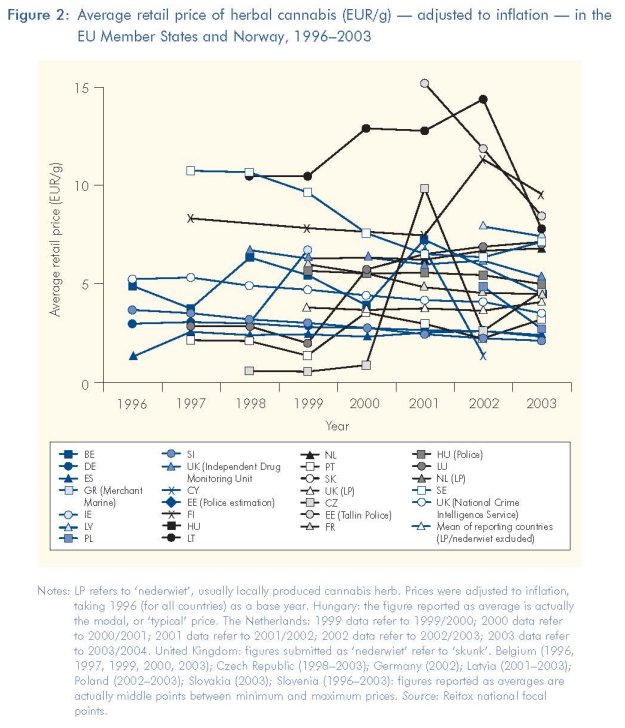

Changes in the average prices of herbal cannabis are less clear than those of cannabis resin. Indeed, Figure 2 does not show a clear overall EU trend of such prices in reporting countries, except for a fall in 2003 in a majority of countries. Over 1996-2003, however, the EU mean (13) of reported prices increased overall, with a peak in 2001 and a fall since then (14). In most of the countries reporting for at least four years, herbal cannabis prices have remained stable or have decreased (15), while an upward trend was reported by the Czech Republic, Latvia, Luxembourg and Portugal. The average price of locally produced herbal cannabis has been declining in recent years in both of the countries that are able to report on the price of these products separately (Netherlands, United Kingdom).

Time trends of the average price of both resin and herbal cannabis have also been reported by 15 EU Member States (16). Comparisons between prices of both products (9 show that over the period 1996-2003, the average price of resin was overall higher than that of herbal cannabis in all but two of the reporting countries, although this difference was not often strongly pronounced. Additionally, trends in the average price of both products by country are similar in all the reporting countries, except France, which reported an overall fall in herbal cannabis prices and an increase in average resin prices. Lastly, reported data show a possible convergence between average prices of cannabis resin and herb in many countries.

Potency

The potency of cannabis products is a topic considered in detail elsewhere in this monograph and so will only be briefly considered here. Potency of cannabis is usually defined as the tetrahycirocannabinoi (THC) content by percentage. Both practical and methodological difficulties mean that data on cannabis potency must be viewed with some caution. For example, the number of samples analysed varies greatly between countries (from four to over 3000 samples in the 2003 data submitted to the EMCDDA) and, thus, the representation of samples in a given user population may be questionable. Furthermore, there are analytical difficulties in the precise and accurate determination of the potency of cannabis products (EMCDDA, 2004) and considerable variations in both the practice of taking samples from cannabis cultivation sites for analysis and that of sampling parts of the material to be analysed (ENFSI, 2005). All of these reasons mean that there is a need to improve and standardise approaches in this area if the reliable monitoring of cannabis potency is to be achieved. As stated above, it is important to distinguish between different types of cannabis (resin and herbal cannabis) — especially when considering potency. Theoretically, a further distinction should be made whenever possible between imported herbal cannabis and home-produced herbal cannabis, although in practice very few countries can systematically report data separately. For all types of cannabis the assessment of trends over time are hampered by a lack of historical data, with only a couple of countries reporting before 1999.

Cannabis resin potency

Compared with prices, cannabis potency is reported by fewer countries but still shows considerable variation. Average potencies of cannabis resin in 2003 varied between less than 1% and nearly 25%, with a majority of countries reporting average potencies between 7% and 15%. The range of values upon which average potencies are calculated was very wide in some countries — raising questions about how meaningful the reported average values are for describing the cannabis market. An extreme example is in Slovakia, where there is a difference of 53 percentage points between the lowest and the highest potencies found. Out of the 16 countries reporting data on resin potency in 2003, eight report minimum values under 1% while seven report maximum values over 25% (three of which report maximum values of 40% or over). Given that much of the cannabis resin consumed in Europe is produced in North Africa under similar conditions, these differences are difficult to explain (see GameIla, this monograph). Data available show an overall (moderate) increase in the average potency of cannabis resin since 1999, although there has been a decline in 2002 in a majority of reporting countries.

Herbal cannabis potency

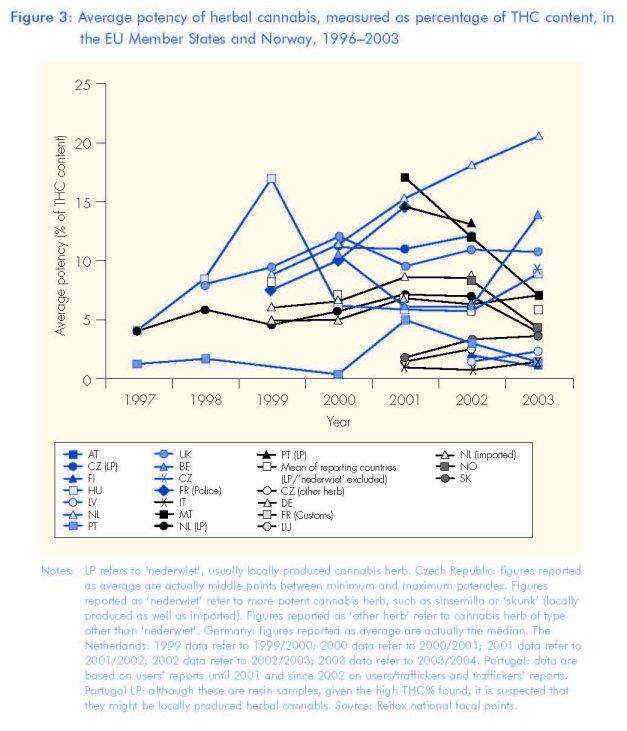

The average reported potency of herbal cannabis in 2003 was generally lower than that of resin in all countries, with the exception of the United Kingdom. Reported values ranged from less than 1% to nearly 14%, with half of the countries (18) reporting estimates of between 4% and 9%. Locally produced herbal cannabis is now available in most EU countries, and when produced under intensive conditions it can be of high potency. Only the Netherlands was able to provide a separate estimate in 2003 for this type of product (20.3% THC on average). It is hard to observe any overall clear trend for the EU in the potency of herbal cannabis in general over the last five years (see Figure 3). At a national level some countries reported a modest increase. Elsewhere, a relatively stable situation can be observed. Overall, the mean value (19) of the reported averages of herbal cannabis shows little variation over the period 1999-2003 (9. The reported potencies of locally produced herbal cannabis where these data are available show an increase in the Netherlands, and a relatively stable situation in the Czech Republic. In both countries the estimated potency of home-produced herbal cannabis exceeded that of cannabis resin from 2002.

Similar trends in resin and herbal cannabis potency?

Data available from 12 countries allow a time trend comparison of the average potency of both resin and herbal cannabis. Although resin potency was estimated as higher in 2003, this was not necessarily the case in previous years: only two countries reported resin as having a consistently higher potency than herbal cannabis. Overall trends are difficult to define. Data available show similar trends in resin and herbal cannabis potencies in France (customs data) (21), the Netherlands and Slovakia. In France both resin and herbal potencies showed a moderate increase from 1997-2002 and then a decrease in 2003. In the Netherlands and Slovakia, average potencies of all cannabis products have been increasing (1999-2003 in the Netherlands, 2001-2003 in Slovakia), although the increase for resin (and locally produced herb in the Netherlands) was much steeper. In the United Kingdom too, overall trends in the potency of resin and herb in the period 1998-2003 are similar, although the potency of resin increased steadily while the potency of herbal cannabis fluctuated greatly within the general upward trend. Austria (2001-2003) and Italy (1999-2003) (22) reported the opposite trend in resin and herbal cannabis potencies. In Austria, resin potency decreased from 2001 to 2002 then increased in 2003, while the potency of herbal cannabis increased and then decreased. In Italy, cannabis resin potency increased until 2002 then decreased, while the potency of herbal cannabis decreased then increased. Although these reports must be checked against data for future years, trends reported in 2003 suggest a convergence between potencies of cannabis resin and herbal cannabis in some countries — Belgium, Italy, Latvia and the United Kingdom (").

Perceived availability

In addition to market information, the availability of drugs has been a part of questions posed in surveys of both general and school populations. Surveys allow researchers to get information on the perception of availability and behaviours of the population in terms of reported use or non-use of illicit substances. Availability questions have been used in a number of surveys in Europe, though with no standardisation of approach. Thus, differences in formats, variables and answering modalities make comparisons and analysis difficult at the EU level. The EMCDDA is currently working with Member States to develop a new module on drug availability in the existing European Model Questionnaire (EMCDDA, 2002) for population surveys. Recently, guidelines have been developed to include questions on exposure (offers or propositions of drugs and opportunities to use drugs), perceived availability (subjective assessment of drug availability based on current individual circumstances) and access to drugs (how, where and from whom to get drugs in individuals' current situations).

Currently, the only cross-European source able to provide standardised data on perceived availability is the ESPAD (2005) school survey series (European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs) (see Hibell, this monograph). This is a repeated survey carried out among 15-16-year-old students in 26 to 35 European countries in 1995, 1 999 and 2003. The survey allows a comparison to be made on the perceived availability of cannabis across the EU Member States and Norway for the age group sampled. Results for 2003 show that getting 'hashish or marijuana' was reported to be 'fairly easy' or 'very easy' by 40-60% of the students in the Czech Republic, Denmark, Ireland, France, Italy, Slovenia, Slovakia and the United Kingdom; by 25-40% in Poland, Portugal and Norway; and by 10-25% in Estonia, Greece, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, Malta and Sweden. The percentage of those finding it fairly or very easy to get cannabis has been increasing overall since 1995 in the Czech Republic, Estonia, Italy, Lithuania, Hungary, Poland, Slovenia and Slovakia, and at a more moderate rate in Cyprus, Denmark, France (24), Latvia, Malta, Portugal, Finland, the United Kingdom and Norway, while the reported ease of getting cannabis decreases in Ireland, Greece (25) and Sweden.

These differences broadly reflect patterns found in consumption data in the EU Member States and Norway between aggregated data on perceived availability of cannabis and lifetime prevalence of cannabis use in this population — demonstrated by a strong linear correlation for the years 1995 (r =0.91), 1999 (I- = 0.81) and 2003 (r= 0.90). There is also a relatively strong correlation between changes in perceived availability of cannabis and changes in lifetime prevalence of cannabis use, between 1995 and 1999 (r =0.83) and between 1999 and 2003 (r= 0.62).

Discussion

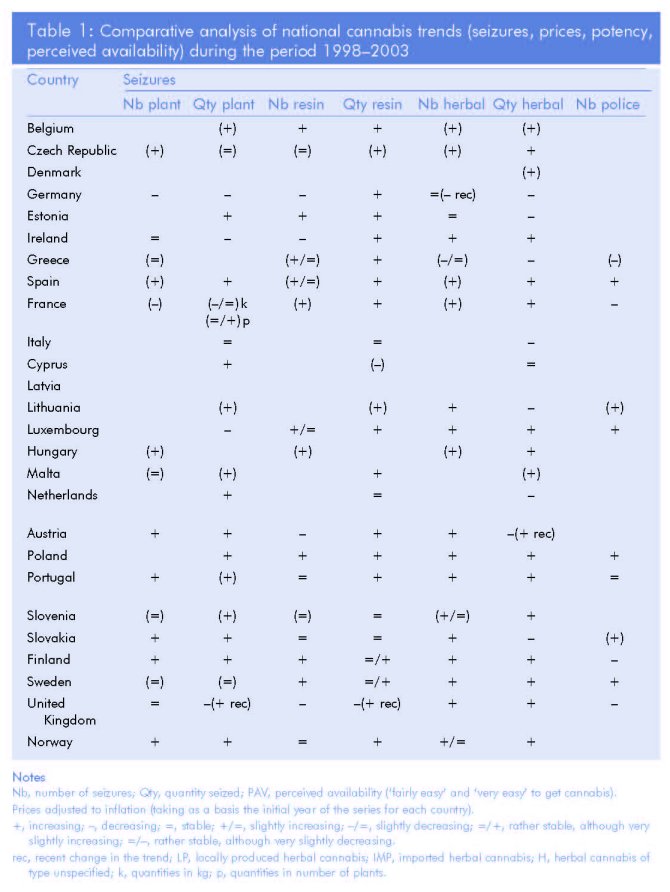

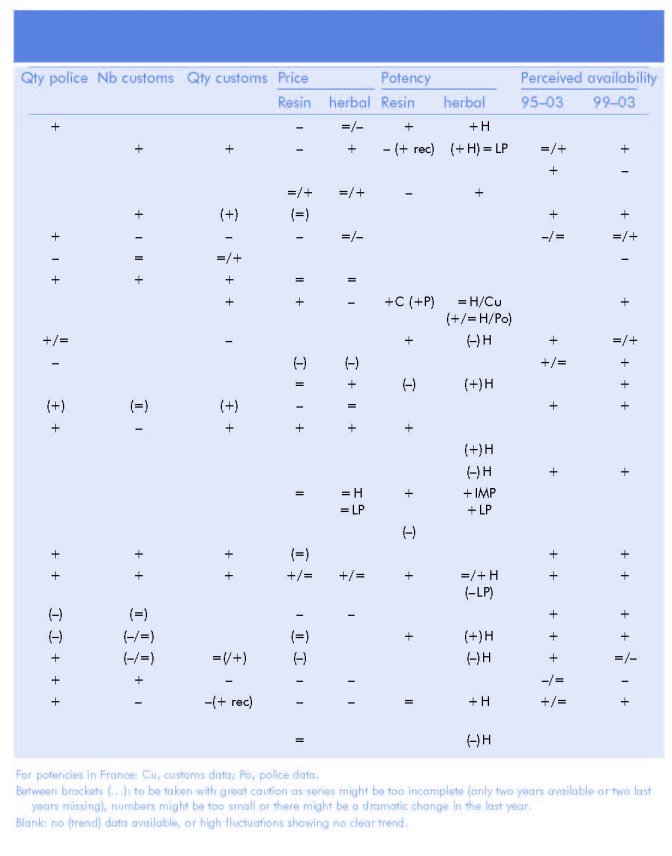

Clearly, many methodological challenges exist regarding the interpretation of data on seizures in general (26), the analysis of data on price and potency, and understanding data on perceived availability in general and school populations. One of them, not yet mentioned, is that available data may indicate changes in different parts of the population. Indeed, changes in the perceived availability in one group of young people (which uses only a small proportion of all the cannabis consumed) may indicate something else than, for example, changes in seizures or potency. Yet, if analytical difficulties are put aside for a moment, a simple comparative analysis of the national trends in each of the indicators over 1998-2003 (") can be constructed. This can be seen in Table 1 (pp. 232-233), which summarises the trends per indicator and per cannabis product that available data show.

Existing data point towards increasing availability of cannabis products in four countries. In Belgium, there seems to be a clear trend towards the increasing availability of both resin and herbal cannabis, based on an upward trend in seizure and potency data and a downward trend in cannabis prices. In the United Kingdom too, the availability of both products seems to be on the increase, although this is comparatively less clear-cut as seizure and perceived availability data experienced shifts in trends. Data from France point towards an increasing availability of herbal cannabis, while it is less clear that this is also true for resin. In the Netherlands, the availability of locally produced herbal cannabis seems to be on the increase, while that of resin and (imported) herbal cannabis might be said to have remained comparatively stable, or have slightly increased, during this period.

In other countries the picture is less clear, or there is simply insufficient information available to judge. In Italy, Lithuania and Slovakia data point to a possible increase in the availability of resin, while in Spain, Portugal and Slovenia data seem to indicate an increase in the availability of both resin and herbal cannabis. In Ireland it is not clear whether data point to an increasing availability of both herb and resin (especially at retail level as quantities seized by customs are decreasing) or to a stable trend. And in Poland there is a possible increase in availability of cannabis in general (data do not allow for more specificity). It should be noted, however, that data may point to decreasing availability in Greece at the retail level, in particular for herbal cannabis, and in Germany, with respect to resin.

Conclusion

It is not our intention here to suggest that this simple analysis can be anything but exploratory. However, it is helpful in illustrating the difficulties in producing an operational research and analysis framework for the concept of availability, especially for a drug like cannabis. The first of these difficulties is the simple observation that availability is a very difficult concept to separate out from that of prevalence. Trying to decide this from available indicators risks asking chicken-or-egg type questions. For example, perceived availability can be seen as closely associated with levels of use, as can some seizure data. That said, there may still be a use for a general concept of availability that is not simply reducible to an indirect reflection of prevalence. Clearly, both conceptual and modelling work is required here if a more robust and useful conceptual framework for thinking about drug availability is to emerge.

A second general observation regards the need to improve both the availability and quality of data sources. In all the data sources discussed above, some progress has been made in moving towards common approaches, definitions and reporting standards. But in comparison to other areas of monitoring much remains to be done and at present any attempt at identifying trends is severely limited by the available time-series data. This is a particular problem for cannabis because there are particular methodological and practical problems to overcome in some of the areas of data collection, such as assessing potency or the amount of plant material seized. Additionally, at least three, and possibly more, major product types exist and trends in availability vary by each type and may be different in different countries. Trends in the availability of herbal imported cannabis, cannabis resin and cannabis grown with the EU may all be different and yet at the same time are all important in understanding the overall availability of the drug. Currently, data sources are simply not sufficiently developed to elaborate this complexity adequately. In conclusion, if cannabis has, as many believe, become a more available drug in Europe, it is difficult to show it convincingly using the available data. If the concept of availability is to remain a key target for drug policy then investment is required in improving the availability of data necessary to measure changes in this area, as is conceptual work to better understand and define the concept of availability itself.

(1) Drug availability appeared in the EU political debate in the mid- to late-1990s. One of the four initial aims of the UK 10-year (1998-2008) Drugs Strategy, 'Tackling drugs to build a better Britain' (UK Government, 1998), was 'to stifle the availability of illegal drugs on our streets'. It was soon followed by a similar target (Target 4) at the EU level in the EU Drug Strategy 2000-2004 (European Council, 1999), 'to reduce substantially over five years the availability of illicit drugs', while the EU Action Plan 2000-2004 (European Council, 2000) emphasised a monitoring approach of this issue in its call for the development of 'indicators of availability of illicit drugs (including at street level) and drug seizures' to be supported by the EMCDDA and Europol.

(2) Caution is required on the reporting of herbal and plant seizures, as practices might vary by country, possibly leading to the incorrect categorisation of one type of substance into either herbal or plant seizures.

(3) Reported by 17 countries (data not available for Denmark, France, Italy, Cyprus, Latvia, the Netherlands, Poland, Slovenia and Sweden).

(4) However, data on the number of seizures made were not available for countries seizing the largest quantities — Italy and the Netherlands.

(5) Reported by 19 countries (data not available for Denmark, France, Italy, Cyprus, Latvia, the Netherlands and Slovenia).

(6) Dividing quantities seized by numbers of seizures.

(7) The Human Development Index is a composite index measuring the average achievements in a country in three basic dimensions of human development: a long and healthy life (measured by life expectancy at birth); knowledge (measured by the adult literacy rate and the combined gross enrolment ratio for primary, secondary and tertiary schools); and a decent standard of living (measured by GDP per capita in purchasing power parity (PPP) US dollars) (UNDP, 2005).

(8) Taking as a basis EU-25= 100 (source: ).

(9) The correlation coefficients in the EU-15 in 2003 were: 0.66 between resin price and HDI; 0.46 between resin price and GDP (per capita in PPS (purchasing power standard)); 0.54 between herbal cannabis prices (type unspecified or imported) and HDI; and 0.59 between herbal cannabis prices (type unspecified or imported) and GDP (per capita in PPS).

(10) The correlation coefficients in the new Member States in 2003 were: –0.16 between resin price and HDI; –0.05 between resin price and GDP (per capita in PPS); –0.50 between herbal cannabis prices (type unspecified or imported) and HDI; and –0.34 between herbal cannabis prices (type unspecified or imported) and GDP (per capita in PPS).

(11) Taking 1996 as a base year for the value of money in all countries.

(12) Taking 1999 as a base year for the value of money in all countries.

(13) Arithmetic mean.

(14) Taking 1996 as a base year for the value of money in all countries.

(15) Taking 1999 as a base year for the value of money in all countries.

(16) Belgium, Czech Republic, Germany, Ireland, Spain, France, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Slovenia, Sweden, United Kingdom.

(17) In each country, we have taken the first year of the series of data available (from 1996 onwards) as a basis for the value of money.

(18) Seven out of a total of 14 countries reporting data on the average potency of herbal cannabis in 2003.

(19) Arithmetic mean.

(20) It is actually slightly decreasing over 1999-2003, but variations in the mean can be explained by the fact that the number of countries reporting data has varied over the period, thus affecting the number of countries upon which the mean is calculated; indeed five countries reported data on the average potency of herbal cannabis of type unspecified or imported for 1999 and 14 for 2003. Indeed, the calculated means of the data from the nine countries reporting over 2001-2003 and of those from the seven countries reporting over 2000-2003 are both slightly increasing.

(21) This is also the case in France for the data from the police, but this source reports only data for 2002 and 2003, which limits the analysis of time trends.

(22) As well as in Latvia and Norway, but these countries report only data for 2002 and 2003, which limits the analysis of time trends.

(23) In Germany, too, a convergence was reported, but only in 2001 and 2002 since 2003 data were not available.

(24) Based on 1999-2003 only.

(25) Based on 1999-2003 only.

(26) It is now widely acknowledged that, across countries, drug seizures do not represent the same proportion of the amount of drugs being smuggled into or circulating in a given country, especially as this may vary according to trafficking routes and location of production areas. We have assumed for this analysis that there is a somewhat positive relationship between cannabis seizures and its availability on the national market.

(27) However, trends in perceived availability in school surveys have been included for both 1995-2003 and 1999-2003, as considering only the latter trend means calculating a trend between only two measures, which is quite limited.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Reitox network of national focal points and their national partners for providing the data on which this analysis is based, as well as Bjeirn Hibell for his useful comments on this paper.

References

European Council (1999), European Union drugs strategy (2000-2004), CORDROGUE 64 REV 3, 12555/3/99, 1 December.

European Council (2000), EU-action plan on drugs 2000-2004, CORDROGUE 32, 9283/00, 7 June.

European Council (2004), EU drugs strategy (2005-2012), CORDROGUE 77, 15074/2004, 22 November.

European Council (2005), EU drugs action plan (2005-2008), Official Journal of the European Union C 168/1,8 July.

European Network of Forensic Science Institutes (ENFSI) (2005) Workshop on cannabis potency, Sesimbra (oral communications).

EMCDDA (2002), Handbook for surveys on drug use in the general population — final report, EMCDDA Project CT.99. EP.08 B, European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, Lisbon.

EMCDDA (2004), 'An overview of cannabis potency in Europe', EMCDDA Insights 6, European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, Lisbon.

EMCDDA (2005), Annual report 2005: the state of the drugs problem in Europe, European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, Lisbon.

Hibell, B., Andersson, B., Bjarnasson, T., Ahlstrôhm, S., Balakireva, O., Kokkevi, A., Morgan, M. (2004), The ESPAD report 2003 – alcohol and other drug use among students in 35 European countries, The Swedish Council for Information on Alcohol and Other Drugs (CAN) and Council of Europe Pompidou Group, Stockholm.

Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP) (2002), Estimation of cocaine availability — 1996-2000, Office of National Drug Control Policy: Washington.

Reitox National Reports (2002-2004) www.emcdda.europa.eu/index.cfm?fuseaction=public.Content&nNodelD=435 Reitox Standard Tables (2002-2004).

UK Government (1998), Tackling drugs to build a better Britain – the government's ten-year strategy for tackling drugs misuse/Guidance notes, The Stationery Office.

UNDP (2005), Human development report 2005 — international cooperation at a crossroads; aid, trade and security in an unequal world, United Nations Development Program, New York.

UNODC (2005), 2005 world drug report, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Vienna.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|