Report 4 Discussion of findings

| Reports - A Report on Global Illicit Drugs Markets 1998-2007 |

Drug Abuse

3 Discussion of findings

The focus of the discussion in this report will be on identifying major changes and trends in individual countries and on a basic comparison of these changes and trends between these countries. Central questions will be:

• Have there been significant changes within the last decade in the drug problems in the three domains we distinguished, i.e., supply, demand and harm in certain countries?

• Have there been significant changes within the last decade in the drug policy response to these problems in certain countries?

• Can we identify certain trends in the developments of problems and policy in (groups of) countries, which share particular characteristics?

We also highlight some unexpected or remarkable findings.

However, the scope of this report is limited and is not intended to serve as an in-depth, detailed description and comparison of how drug problems and drug policy have developed over the last ten years in the selected countries. Nor will it give a full picture of global developments.

In this report we have included specific references only when using information additional to that which was presented in the country reports. References for all other information on the countries dealt with in this report can be found within the country reports (see appendix at the end of the total volume).

3.1 General remarks

Before discussing the findings we would like to make some general remarks about the data in the country reports. A comparison between countries and in one country over time is far from easy. This is even sometimes the case for countries with solid data collection like the EU Member States because there are substantial differences in the data collected (age group definitions when it comes to prevalence data, different years when certain data are collected, differences in methods of data collection, variations in detail and differentiation level, etc.). In other countries data collection is relatively weak, especially in developing and transitional countries. The drug problem is just one of many issues that these countries are facing besides other pressing issues like economic development, for instance. For most of the transitional and developing countries we selected it was difficult to find sound data, in particular on the situation a decade ago. In some countries the weakness or unavailability of data made it simply impossible to go beyond a rough and rather tentative picture.

Given that we selected countries for our sample to cover the different aspects of the drugs problem and drug policy it is clear that the selected countries differ substantially with regards to data on the indicators. For example, some countries are more affected by production or drug trafficking, whereas others are more affected by consumption. Countries also differ with regards to the nature in which they are affected by production, trafficking or consumption of one or more of the four substances we selected for our study (opiates, cocaine, ATS and cannabis), and the extent to which they are affected. As these four selected substances in fact represent four groups of substances, there are also major variations in the specific substances used in each country. Therefore for each country we specified the most commonly used substance (e.g., ‘chorny’, a homemade opiate, in Russia, as well as heroin; Captagon (amphetamine) tablets in Turkey; and various pharmaceutical drugs in India (Morphine, Pethidine and Pentazocine, among others).

Some of the selected indicators for drug policy responses cover all substances, especially if they are more generic, like drug prevention. In other cases, drug treatment for example, the focus is primarily on heroin (or opiates). Specific treatment for problem use of substances other than heroin is still quite rare, and limited to a few Western countries.

It is interesting to see that in the field of drug policy we found considerably less diversity than in the field of drug problems. The policy response in the majority of countries appears to be rather similar, at least when examining official statements in policy papers and drug laws. We will come back to this point in the chapter on drug policy issues.

Finally, we would like to emphasise that specific changes of drug problem features cannot be explained as simply results of policy measures taken (Reuter & Pollack, 2005).

3.2 Drug problems

In the discussion of the drugs problem we will follow the structure of the three domains, supply (production, trafficking and retail), demand (experimental or recreational use and problematic or chronic use) and harm (drug-related harm to the user and to society).

3.2.1 Supply

To assess supply as part of the drugs problem we selected two indicators. For production we worked with an assessment of quantities produced (specified per substance, generally assessed in kg or in some cases as other units, e.g., cannabis plants and Ecstasy tablets). For trafficking we focused on the international market, covering export, transhipment and import, and used seizure data as indicator. Seizure data are the only reliable data collected on supply in the majority of the countries selected for our study and in many other countries.

Strictly speaking seizure data are not an indicator for trafficking. Only a limited percentage of trafficked drugs are seized. There are no reliable estimates as to what these percentages are. The quantity seized is a function of three factors: domestic demand, transhipments and the effectiveness of interdiction efforts. The latter cannot be assessed solely by the budget invested by a country in measures against trafficking but also by the quality and effectiveness of investigations into trafficking activities and of the actual operations undertaken. Moreover, not all drugs seized are meant for cross-border trafficking; they could also have been domestic supply for the domestic market. A total quantity of seized drug per year alone is not a good enough indicator for trafficking. It remains unclear if this quantity contains retail seizures, i.e. small quantities sold on the streets. Combining the total quantity of seized drugs with the number of seizures (and better still, the range of the quantities seized) helps to create a better indication for trafficking and retail. In report 2 on the size of the market estimates are presented for a number of the selection countries where only minimal data were available.

3.2.1.1 Production

Opiates and cocaine

| • The production of opiates and cocaine is concentrated in only a few countries; Afghanistan is by far the main producer of opium, Colombia of coca. • In the past decade there were no changes in production countries, just some shifts in quantities produced per country. |

The production of opiates and cocaine are each concentrated in one country; opium in Afghanistan and coca in Colombia. Afghanistan is one of the poorest nations in the world, with an extremely unstable government. Colombia is a middle income country, with relatively stable economic growth over the last fifty years, but subject to a great deal of political instability.

Afghanistan is by far the major producer of opiates in the world, with around 82 percent of production in 2007 (UNODC, 2008). Myanmar and Laos play a substantial but by far less important role now. Myanmar has seen a substantial decrease in production since about 1998. This is largely due to the actions taken by the quasi-state that governs the growing areas, the United Wa State Army (UWSA). The UWSA has used highly coercive methods, including mass forced migrations, to achieve this; it has been even more coercive than the Taliban when it effectively enforced an opium-growing ban in the last year of its dominance of Afghanistan. Smaller amounts of heroin are produced in Mexico and Colombia (for the United States market) and a handful of other countries. Opiates are also widely produced in the Russian Federation, especially home-made products such as khanka (chorny) and mak, which are basically cheaply made, unrefined opium products. Yet this cultivation accounts for just a small percentage of world production, measured in morphine equivalents. Very low levels of cultivation of opium poppy continue to take place in the Caucasus Region and other CIS countries (Ukraine and some Central Asian countries).

Colombia accounts for the bulk of world cocaine production (55 percent of the global coca bush cultivation) with smaller production in Peru (30 percent) and Bolivia (16 per cent) (UNODC, 2008; Thoumi, 2005). In the period from the 1980s until the late 1990s Colombia gradually developed to become the world’s main producer of coca. “Whereas in the 1980s Colombia was the third most important producer of coca leaves, for the last ten years it has accounted for about two thirds of the total, as well as the vast majority of refining. The shift of coca growing from Peru and Bolivia to Colombia is probably the result both of tougher policies in the other two countries and the massive rural flight in Colombia. The violent conflict in Colombia’s established rural areas has brought farmers to frontiers within the country where there is little infrastructure for legitimate agricultural product and coca growing is very attractive, in part because these are areas in which coca farming is difficult to monitor or police” (Thoumi, 2005). Colombia is unique in the range of drugs that it produces. It also produced a substantial share of the heroin sold in the United States during the period 1994-2004; since then the estimates are that production has fallen by perhaps two thirds. It is not clear why eradication efforts against poppy growing in Colombia have been so much more successful than those against coca growing. During the 1970s Colombia exported a considerable amount of marijuana, again primarily to the United States.

The locations of coca and opium production have been quite stable. Still, only a limited number of countries dominate the production of these substances. It is clear that climate and availability of land play a minor role. Characteristics of government and labour history factors might be more relevant factors.

ATS

| • ATS production is spread over several countries. • The number of production countries has increased over the past decade. • There are new producers, in particular in transitional countries. • ATS production is diverse, from small-scale kitchen laboratories to large industrial-scale laboratories. • There have been shifts in quantities produced from countries with intensified control to countries with less control. |

The production of ATS is spread over several countries, though one can identify some countries as having a substantial share of the global total. Some of these countries are wealthy and well developed. New producers (transitional countries) have come onto the scene but it seems that no country has exited production. The Netherlands plays a significant role in the production of ecstasy and, to a lesser extent, amphetamines. In recent years ecstasy production seems to have declined in the Netherlands and shifted to transitional countries like Poland. The intensified enforcement in the Netherlands might have helped to shift production to countries with weaker drug control measures.

The Czech Republic is one of the world’s major producers of methamphetamine. China has also become a large producing country for methamphetamine. The increase in seizures can be taken as one indicator for this. In the Russian Federation production of ‘vint’ (similar to methamphetamine or ‘pervetine’) and some production of ecstasy (around Saint Petersburg) can be found, but ecstasy seems to be mainly imported from the Netherlands, Poland and the Baltic States, in particular Lithuania. One indicator for the considerable scale of the manufacture of ATS in the Russian Federation is the fact that in 2006 Russian authorities detected 1,700 production facilities for illicit synthetic drugs, including 136 chemical laboratories. Small-scale laboratories and industrial-scale laboratories have also been discovered in the United States, though for the latter a decline was reported from 245 in 2001 to 11 in 2007. Finally, in Turkey a limited methamphetamine production has been reported based on the detection of a small number of laboratories.

Cannabis

| • Cannabis production is reportedly spread over more than 172 countries. • Cannabis resin production is more concentrated than cannabis herb production; the number of countries producing cannabis resin is estimated to be around 58, compared to 116 for cannabis herb production. • An increasing number of countries are involved in cannabis herb production. • Cannabis herb production is very diverse, from small-scale home growing to large-scale agricultural business. |

The production of cannabis is spread over many countries. In the World Drug Report 2007 it is stated that “reports received by UNODC suggest that cannabis production is taking place in at least 172 countries and territories” (UNODC, 2007). Morocco is the world’s largest producer of cannabis resin and the main supplier of Western Europe (UNODC, 2007). In the South-West Asian and Middle Eastern regions, in particular in Afghanistan and Pakistan, considerable quantities of cannabis resin are produced. The production of cannabis resin is more concentrated than cannabis herb production. Based on reports from these countries (ARQ 2002 – 2006 period) UNODC estimates the number of countries producing cannabis resin to be around 58, compared to 116 for cannabis herb production (UNODC, 2007).

Herbal cannabis production can be found in many countries all over the world, involving both large-scale plantation-style cultivation and small-scale non-professional producers. In some cases it is meant largely for the domestic market and, in the case of small-scale home growers, even for personal use by the producer. As with the production of ATS like Ecstasy and methamphetamine in some countries, cannabis production is meant both for the world and the domestic market (with, in many cases, an emphasis on export). Countries (from our sample) producing for the domestic as well as the foreign market are South Africa, Mexico and the Netherlands.

A large part of the cannabis production in Mexico seems to be intended for the United States market. Therefore Mexican criminal organizations have recognized the increased profit potential of moving their production operations to the United States, reducing the expense of transportation and the risk of seizure when crossing the border. Mexican traffickers operating within the United States generally attempt to cultivate higher-quality marijuana than they do in Mexico. This domestically produced sinsemilla

(a higher-potency marijuana) can be sold for between five and ten times the wholesale price of conventional Mexican marijuana. Yet Mexico continues to be the principal foreign supplier to the United States - not only of cannabis, but also of heroin and methamphetamine - as well as the principal conduit for cocaine to the United States. According to UNODC, all three North American countries (Mexico, the United States and Canada) are large producers. “Estimates made available to UNODC suggest that Mexico and the United States may be the world’s largest cannabis herb producers” (UNODC, 2007).

In South Africa large scale cannabis cultivation is reported in small, remote and mountainous, or otherwise inaccessible, parts of the country. In earlier years (1998 – 2001) there was no evidence of plantation-style cultivation in South Africa. In 2007 cannabis plant production was reported as 3,000,000 kg, half of which was for domestic consumption, which makes cannabis the most widely consumed drug after alcohol. The Netherlands and Switzerland are the major producers of cannabis herb in Europe (EMCDDA 2008), yet it is unclear how much of this production is for the domestic market and how much is exported. There have been, for instance, some seizures of ‘nederweed’ in the United Kingdom, Scandinavia, Germany, Belgium and France (EMCDDA, 2008; Legget and Pietschmann, 2008). However the extent of these exports remains unclear (KLPD-IPOL, 2008; Fijnaut and de Ruyver, 2008). Cannabis resin coming from the Netherlands is most probably transhipped from Morocco, through the Netherlands, to other countries. Cannabis resin is barely produced in The Netherlands (UNODC, 2007; KLPD-IPOL, 2008).

Home growing seems to be an expanding phenomenon, which can be found in an increasing number of countries, e.g. the Netherlands, Turkey, the United Kingdom, the United States and South Africa. A variety of cultural factors promote this; in Western countries, for instance, small-scale home growing is sometimes associated with organic cultivation and a healthy lifestyle. Hemp is mystified as a plant with many qualities, which cannot only be applied for pleasure but also for medical purposes and for the production of cloth and carton, playing a crucial role in ‘environment-friendly’ crop growing (Herer et al., 1995).

Discussion

| • Heroin production has increased over the past decade. • Cocaine production is reported as being fairly stable. • Development of ATS and cannabis production levels is unclear. |

For Afghanistan and Colombia, drug production is their principal drug problem, since consumption is still not substantial. In Colombia, trafficking and the violence related to it are also important components of the national drug problem. These countries produce opiates and cocaine primarily for the world market. In the Netherlands Ecstasy production is just one of the drug problems besides trafficking and consumption. The Netherlands plays a substantial role in trafficking cocaine and Ecstasy. The drug use problem in the Netherlands involves all four substances, with prevalence figures around average for EU Member States.

Global production trends over the last decade varied for the four substances. Heroin production has grown substantially over the period 1998-2007, particularly since 2004 notwithstanding the decline in production in Myanmar and Colombia. Cocaine production has been fairly stable over the same period, with some years of decline followed by increases (UNODC, 2008). For ATS and cannabis it is impossible to say how production levels have changed. Though there is evidence that the number of countries involved in ATS and cannabis production did increase along with the production spread over these countries – the latter seems to be true in particular for cannabis – there are no good data to make clear-cut statements about quantities produced. UNODC states that global amphetamine production appears to be rising (UNODC, 2007) and that there are indications of an overall stabilisation in the market in 2005, but it remains to be seen whether this will emerge as a long-term trend (UNODC, 2007) (see also report 2). UNODC claims that both global cannabis herb and cannabis resin production declined in recent years,2 yet these calculations are rather uncertain, as is conceded by UNODC: “Cultivation and production of the drug is extremely widespread. Unfortunately some of the same qualities of this pervasiveness impede any practical and rigorous reckoning of production” (UNODC, 2008).

3.2.1.2 Trafficking

| • Seizure data do not allow statements about quantities trafficked; they give indications for changes in trafficking routes. • Changes in seizures reflect policy investment rather than trafficked quantities. |

Our focus here has been on international trafficking and on drugs rather than on precursors. The quantitative basis for this study is the seizure data, which we found on the countries in our sample, mainly from EMCDDA sources and UNODC’s World Drug Report, complemented with some additional information from other international publications and experts in the selected countries. Seizures are the only trafficking indicator available but, as mentioned earlier, it is an extremely imperfect indicator.

With regards to drugs trafficking we found major differences between the countries in our sample. We selected some countries for which transhipment is a major element of their drug problems; in some cases it is even the major element. This is the case in Brazil, Turkey and also Mexico, though in Brazil and Mexico drug use is also developing into a significant societal problem. Cocaine trafficking is a major problem in Brazil; there has been a steep rise in drug seizures (quantities) in Brazil in the past decade (between 2001 and 2006), not only for cocaine and cannabis herb, which are transhipped in substantial quantities,3 but also for heroin and cannabis resin, which are transhipped in relatively modest quantities for a country of 200 million inhabitants4 (UNODC, 2008). Mexico does not show the same consistency as Brazil. It is a major transhipment country for cocaine making its way to the United States and plays a relatively modest role in the transhipment of heroin from Colombia to the United States. In the past ten years Turkey has shown an increase in seizures (quantities) of opium and heroin, cannabis and ATS.

There are countries in which the trends in seizure quantities are in line with the consumption trends. For instance, in Australia one can see a decrease in lifetime prevalence (LTP) and last-year prevalence (LYP)5 of heroin and cannabis use (between 1998 and 2007) and at the same time a decrease in heroin and cannabis seizures. But there are also countries in which the seizure trends are not in line with consumption prevalence. This is, for instance, the case in Turkey, where the seized quantities increase while drug use prevalence grows only moderately. An explanation for this may be that Turkey is a transhipment country (with a very limited domestic spread of the transhipped drugs), whereas Australia is a destination country for drug trafficking.

Then again, there are destination countries that show growing use prevalence for a certain drug but falling seizure quantities for the same drug. Portugal is one example of this, where cannabis use increased between 2001 and 2007 (LTP and LYP in the general population of 15-64 year-olds and among young people aged 15-24) but seizure quantities are falling overall in the same period.6 With regards to cocaine, Portugal – according to UNODC - emerged as “the second most important European point of entry” (UNODC, 2007), perhaps reflecting its historical ties to Brazil. This change into a transhipment country (again with a limited domestic spread of the transhipped drug) is reflected in the increasing seized quantities7 but comparably low use prevalence data (LTP and LYP in the general population of 15-64 year-olds and among young people aged 15-24). The diverging development of seizures – decreasing seizures for cannabis and increasing seizures for cocaine – can be seen as a reflection of the priorities of Portuguese drug policy; a decrease in trafficking is one of the key priorities but special attention is paid to trafficking through Western African countries. Finally, there are without doubt transhipment countries where some drugs ‘fall off the wagon’. Brazil and Mexico are illustrations of this (see above).

2 Cannabis herb production is reported to have decreased from 7,000 mt in 2004 to 42,000 mt in 2005 (UNODC, 2007) and stabilised in 2006

at around 41,000 mt (UNODC, 2008); cannabis resin production fell from around 7,500 mt (range 3,800 – 9,500) to 6,600 mt (range

4,200 – 10,700) (UNODC, 2007) and to 6,000 mt in 2006 (UNODC, 2008).

3 Cocaine: 9,137 kg in 2001 and 14,324 kg in 2006; cannabis herb: 146,280 kg in 2001 and 166,780 kg in 2006.

4 Heroin: 12 kg in 2001 and 95 kg in 2006; cannabis resin: 44 kg in 2001 and 96 kg in 2006.

5 Lifetime prevalence: if a person has ever used a certain drug; Last-year prevalence: if a person has used a certain substance in the last year.

6 Cannabis herb: 361 kg in 2002, 119 kg in 2004 and 152 kg in 2006; cannabis resin: 6,473 kg in 2001, 31,556 kg in 2003 and 8,458 kg in 2006 (UNODC, 2008).

7 5,575 kg in 2001 and 34,477 kg in 2006 (UNODC, 2008).

3.2.1.3 Retail

Retailing itself can be part of a nation’s drug problem. The locations that serve as retail markets can be the source of disorder and crime.

Thus it would be useful to have indicators of various aspects of the retail market and to track how they have changed over time. Unfortunately there are no indicators available on a systematic basis. Anecdotally, it appears that the disorder and concentration of retail markets in cities in the United States have declined over the last few years, with an accompanying reduction in violence. However that is no more than an impression. In report 2 (on the size of the market) we provide estimates of retail sales but there is otherwise no information about retail activities as part of the drugs problem.

3.2.2 Consumption (demand)

We decided to use the term ‘consumption’ instead of ‘demand’ as the available data collection in fact measures consumption quantities and not demand, a relationship between quantity and price. For consumption we used two indicators: the number of experimenting / recreational users and the number of problematic / frequent users. Data on quantity are so rare that this important dimension is not discussed here, but the available figures are considered in report 2. For information on experimental or recreational use we used prevalence data (primarily LTP and LYP) from ESPAD, household surveys, etc. Reliable prevalence data cannot be found in all countries; in developing countries and some transitional countries these estimates simply do not exist or are of poor reliability and validity. Data on problematic drug users are often lacking in developing countries; we found hardly any data in Colombia, Mexico, Brazil and South Africa.

Report 6 (on methodological limitations) provides a detailed discussion of the limitations of the data underlying these indicators; here we provide just a brief summary. Population prevalence rates come from surveys that use different questions, interview modes (e.g., in person, by telephone, by mail) and age ranges (e.g., over 12, 14-59); this limits comparability across countries.

These surveys provide good indicators of trends in occasional use of many drugs. They are, however, of little value in estimating the size or rate of change of the much smaller populations that use expensive drugs frequently. These populations have high rates of homelessness, lead erratic lifestyles that make them hard to contact through a survey and have high rates of interview refusal and under-report consumption. As a consequence, in every country where efforts have been made to develop estimates of the extent of ‘problem drug use’, the term preferred by the EMCDDA, they have been found to be much higher than suggested by the surveys.

A major problem is that there is no generally shared definition of experimental or recreational use, or of frequent or problem use. Overall, experimental use tends to refer to a short period of ‘trying’ a certain substance, whereas recreational use also covers more regular, but non-dependent use of a substance. Also in different countries, different terms and different definitions are used for problematic (or problem) and/or frequent use. The EMCDDA defines problem drug use as the use of drugs by injection and/or the regular or long-term use of opiates and amphetamine-type drugs and/or cocaine. In the United States, data are collected on chronic users. In some countries the data collection is limited to injecting drug use.

We used treatment data and data on drug-related harm as indicators for frequent or problem use. Despite the fact that many countries, especially again the Western countries, collect data on numbers of drug users in treatment and – to a lesser degree – data on the extent of problem use, the used definitions and quality of the data differ substantially. So, again, the comparability of the available data is limited.

3.2.2.1 Lifetime and Last-Year Prevalence

| • Cannabis use prevalence dominates in Western countries (between 30% and 50% LTP). • Prevalence figures in Western countries show long waves but - in some countries - considerable fluctuations in cocaine and ATS use. • Prevalence figures are stabilising in some (advanced) transitional countries in the past decade. • Drug use prevalence increased in developing countries. |

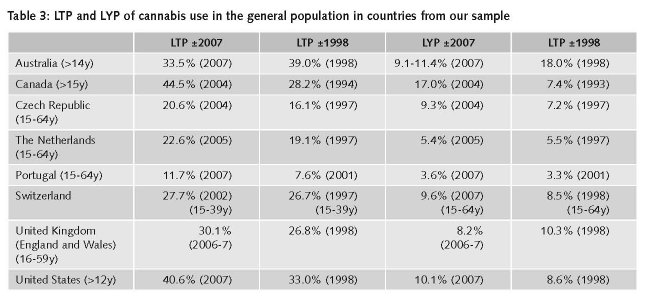

Drug consumption characteristics vary a great deal across countries. There are major differences in substances used, in prevalence and how prevalence has changed in the past decade. One example is cannabis use. It is the foremost popular drug in Western countries with high LTP in the general population and in particular among young people. This is true for most EU member states, the United States, Canada and Australia. However, in recent years these figures are stable or falling in many of these countries. Australia is an extreme: there has been a substantial decline, e.g. in LTP (in the general population) from 39.0% in 1998 to 33.6% in 2004. LYP (in the general population) fell from 18.0% in 1998 to 11.4% in 2007. Transitional and developing countries show an inconsistent picture. In the Russian Federation, China and India the prevalence may be rising but is relatively low compared to Western countries.

Another example for variations in drugs preferences and prevalence is heroin use, which in a number of countries - after a serious epidemic – is stabilising or even decreasing. Examples are Hungary and the Czech Republic. The development in these countries shows signs of at least a partial stabilisation of prevalence of illicit drug use. After a period of a rather steep increase per year the prevalence curve of illicit drugs use is reported to be flattening, showing relatively modest prevalence variations from year to year. In recent years – from around 2003 onwards – the prevalence figures, especially for opiates, stabilised and even decreased, whereas cannabis and ATS are increasing. In both countries, especially cannabis lifetime prevalence among young people rose, as can be shown by the LTP figures taken from the ESPAD.8

This (partial) stabilisation might be an indication of having reached the peak of the epidemic and being on a par with Western countries that generally have relatively stable prevalence figures, as can be seen from other countries in our selection, such as the Netherlands, Sweden and the United Kingdom. The prevalence figures of these countries show fairly modest fluctuations in prevalence of use of different substances but hardly any sharp rise or fall. Yet there are Western countries showing substantial fluctuations for cocaine and ATS. Australia is one example of this. In the years between 1998 and 2007 LTP and LYP (in the general population) increased significantly for Ecstasy and – to a lesser degree – for cocaine. In the same period LTP and LYP decreased (in the general population) considerably for meth/amphetamines.

Although there have been changes in drugs preferences in some countries, others show considerable stability. Sweden and other Nordic countries have seen a consistent level of amphetamine use over a long period of time.

For the Russian Federation the picture is less clear. Solid prevalence data are lacking for recent years; even less is available for 1998. A reliable picture of how the drug problem has evolved in the past ten years is hard to obtain. However, according to the World Drug Report 2008, the use of heroin and other opiates, cocaine, cannabis herb and resin, amphetamines, methamphetamines and related substances in the RF was stable in 2006. There was, however, some increase in the use of Ecstasy (MDMA, MDA, MDEA) in the Russian Federation in 2006. One alarming sign might be that the average age of first-time users of illicit drugs fell in last decade from 17 to 14. As in the majority of the countries studied, cannabis is Russia’s main drug of choice.

8 In Hungary cannabis LTP (among 15-16 year-olds) went up from 4.5% in 1995 to 11.5% in 1999 and to 16% in 2003; amphetamine LTP for the same group went up from 0.4% in 1995 to 2.3% in 1999 and 3.1% in 2003; ecstasy LTP from 0% in 1995 to 2% in 1999 and 3% in 2003. In the Czech Republic ESPAD figures show a rise in cannabis LTP from 22% in 1995 to 35% in 1999 to 44% in 2003; amphetamine LTP went from 2% in 1995 to 5% in 1999 to 4% in 2003; ecstasy LTP from 0% in 1995 to 4% in 1999 and to 8% in 2003.

For other, mainly developing, countries (China, India, South Africa) the available data suggest rising prevalence of illicit drug use. However, reliable national data on drug use are absent in all three countries. There are some local or regional studies. In South Africa they are predominantly in densely populated regions, e.g., Cape Town, Gauteng (Johannesburg and Pretoria) and Durban. Overall, in international comparison the levels of use of illicit substances seem to be still relatively low. UNODC reports a strong decline in heroin use for China in 2006, but a large increase in cannabis use. Also, for India the number of cannabis users is estimated at 8.7 million but there is no information about change over the past 10 years. Still the prevalence of cannabis use is low compared to Western countries. 8.7 million is less than 1% of the general population (1.148 billion).

Also, in Brazil and Mexico, countries that – though not in transition – are nonetheless facing significant societal changes and social disruption, one can find rising prevalence. Brazil shows relatively high LTP and LYP (for the age group 10-18) for solvents/inhalants, marihuana, benzodiazepines, ATS and cocaine. While in comparison still low, the use of illicit substances has increased over the years. According to UNODC, Brazil has the largest opiate consumer population in South America with 0.5% annual use rate (mainly synthetic opiates, only 0.05% heroin) and the second largest cocaine market in the Americas (around 870,000 persons) after the United States (some 6,000,000 persons) (UNODC, 2008). In Mexico LTP seems to rise for all substances (between 1990 and 2001/2). The same holds for LYP with the exception of cannabis use. For the younger age group (18-29 years), illegal drug use (LTP of marijuana and cocaine) has grown faster than ten years ago and earlier.

Some countries in our selection show features that diverge from what can be observed in countries with similar characteristics. Turkey is one of these interesting cases. It plays a major role as a transhipment country, forming a bridge between continents. From the East (Iran and Afghanistan) there is an important heroin-trafficking route crossing to Western Europe. From the West, Ecstasy is transported from Europe to the East. Many transhipment countries subsequently experience a growth in domestic use of the transhipped substances. For instance, in South-East Asian countries the cities with a relatively high prevalence of heroin use form the visible traces of the heroin transhipment route (Paoli et al., 2009). In Turkey, however, the prevalence of the transhipped illicit substances remains relatively low. There has been an increase in drug use over the years, but heroin use especially is rather low compared with the use of cannabis and synthetic drugs and with rates in Western European countries such as the United Kingdom and Switzerland. Ecstasy started to show up around 2003 but the prevalence is still modest: 2% in the 2003 ESPAD (15–16 years). Again, these conclusions are rather tentative as solid data are lacking.

Another interesting case is Canada. It is a startling exception to the rule that prevalence curves in Western countries are pretty steady, showing some fluctuation rather than sharp increases (or decreases). LTP of illicit substances increased dramatically for all substances in the past decade, both in the general population above 15 years of age and in the age group 15 – 24 years. The Canadian Addiction Survey of 2007 states that Cannabis LTP among young people (15-24 years) reached a level of 61.4% in 2004 (the latest available survey). Cannabis is followed by hallucinogens (16.4%), cocaine (12.5%), Ecstasy (11.9%), Speed (9.8%) and inhalants (1.8%). Yet there are major differences between data sources, probably due to differences in methods used. However the available data are consistent regarding the picture of substantial growth in prevalence of illicit substance use over the past decade. LTP of cannabis, cocaine/crack, LSD/hallucinogens, speed and heroin increased significantly as did LYP of cannabis. Studies show that crack use has become increasingly prevalent in street drug-use populations across Canada in the past ten years, although considerable local differences exist.

3.2.2.2 Problem drug use

| • Figures for problem drug use are rare and weak. • Problem drug use seems to be fairly stable in Western countries. • There are indications of a stabilisation or even decline in transitional countries. • In developing countries, problem drug use seems to be increasing, though there are indications of stabilisation, especially for opiates. |

Data on problem use are particularly weak, even in Western countries. This may be seen as an indication of the inherent difficulty of estimating this target group on a national level. There are extreme differences in estimates as, for instance, in Canada where two estimates of the number of heroin users (probably an important part of the population of problematic drug users) are 35,000-40,000 for 2002/2003 and another is 80,000 opioid users. There is one estimate of the number of injecting drug users (IDUs) of 125,000 for 2000/2001, while another shows a range of 50,000-90,000. Figures from other countries show a similar picture. Trend data for the past decade are hard to find.

For developing countries the situation is even worse. In some countries, e.g., in Brazil, Colombia and South Africa, there are no estimates at all. In some others, available estimates are not useful, due to the large differences between them. For instance, this is the case in Turkey where the estimate of IDUs varies between 0 and 100,000.

The picture we found regarding problem use of illicit drugs in our sample of countries is quite similar to what we described above in terms of LTP and LYP. Again, Western countries show relatively stable (sometimes even falling) prevalence figures. This trend can be seen in Australia, the Netherlands and Sweden. This also includes countries that went through a transition phase, such as the Czech Republic and Hungary. In the Czech Republic problem opiate use is reported to have decreased in recent years (based on treatment data) whereas the number of problem pervitin users increased (8%) between 2003 and 2004. In Hungary injecting drug use was reported to have dec reased between 2002 en 2005. On the other hand, there was a 10% increase in 2006. The primary explanation for that increase is the 15% rise in the number of injecting heroin users in treatment. The estimate of injecting drug use is based on treatment data. Injecting use of other substances has been virtually non-existent.

The Russian Federation shows signs of a stabilising number of problem drug users following a period of dramatic increase since the mid-nineties. According to UNODC the number of drug addicts in the Russian Federation increased by ninefold in the last decade. The impression that the situation has stabilised is supported by the fact that the number of registered drug-dependent persons (350,267 in 2006), including the number of registered opiate users (307,232 in 2006), has remained largely unchanged over the period 2002-2006 (UNODC, 2008).

Data from China point in the direction of an increase in the problem use of heroin and – in particular – amphetamines, in the past decade, though there are signs that heroin use recently is stabilising (or even falling). Noteworthy is the report of a trend towards injecting heroin as opposed to ‘chasing the dragon’9, as the first involves more serious health risks. However, the number of IDUs is unclear. Estimates range from 356,000 to 3.5 million. Besides heroin, methamphetamine, diazepam, pethidine and morphine are the most commonly injected drugs.

One paradoxical finding is that there are countries with stabilizing or even falling LTP (and LYP) whilst showing an increasing prevalence of problem use. One example in our country selection is the United Kingdom. LTP of drug use among young people (16-24) is reported as falling between 2001 and 2006. This is true for the total of illicit drug use. Specified per drug, one can see that LYP for cannabis and volatile substances is falling, LYP for opiates, amphetamines, crack and magic mushrooms are stable and LYP for cocaine is rising. The number of problematic/chronic frequent users in the general population went up (in England and Wales) from 162,544 - 251,000 in 1998 to 397,033 – 421,012 in 2005.

If one takes LTP and LYP as indicators for experimental or recreational use, it might be assumed that LTP and LYP translate, after a couple of years, into corresponding problem use prevalence. However this does not take account of the long duration of drug dependence for many of those who cannot desist early in their using career. Everingham and Rydell (1994) modelled the changing distribution of cocaine use over two decades. They showed that in the early stages of the epidemic in the United States, most users were light users. Over time, some of them became frequent or heavy users, consuming on average a much larger quantity per annum. By the early 1980s the number of users had started to decline but the share of all users who were heavy users had risen; that resulted in a larger total quantity consumed. Thus declining prevalence can be accompanied by rising seizures in the middle stages of an epidemic.

3.2.3 Drug-related harm

The concept ‘drug-related harm’ covers health damage for the drug users as well as all the adverse consequences for society, such as crime, disorder and communicable diseases.

9 Chasing the dragon is a way of inhaling the drug by heating it on a foil and breathing in the smoke through a straw.

3.2.3.1 Harmful consequences for drug users

| • Numbers of drug-related deaths and HIV positive drug users in Western and advanced transitional countries are fairly stable. • Countries with good coverage of comprehensive harm reduction services have stable or falling rates of drug-related death and HIV prevalence. • Developing countries and countries in full transition show increasing prevalence of drug-related deaths and HIV positive drug users. |

The number of HIV+ drug users and drug-related deaths (by overdose) (DRD) are considered strong indicators for drug-related harm to the user for which relatively good data are available in many countries. We also looked for data on recent (last year) HIV infections among drug users. However, numbers on HIV+ drug users are frequently calculations based on samples and on assumptions of the actual source of infection, either sexual behaviours or injecting drug use. The way they are collected differs substantially between countries. But recently a few global overview studies in the field of HIV prevalence and prevalence of injecting drug use were published that we considered useful for our purpose (Mathers et al., 2008; Cook & Kanaef, 2008).

Drug-related death (by overdose) posed a different kind of a problem. The procedure for determining whether death is the consequence of a drug overdose ranges from a full post-mortem to a superficial medical check by a GP. Nations also differ in how the data are aggregated. However, the comparison of the number of overdose deaths within a country between two different points in time is an important element in our study; these comparisons are more meaningful than cross-country comparisons. Note that we are including only deaths in which drug use was the direct, acute cause. Not included are those in which drug use is the ‘indirect’ cause, e.g. death by drug use-related diseases and accidents; for example, deaths related to Hepatitis B, in which the cause of the infection was previous injecting drug use, are not counted as drug-related deaths. In some countries, e.g. in India, drug related deaths are not monitored at all. By choosing these two indicators for drug use-related harm, our focus is restricted to just three of the four substances selected for this study, i.e. opiates, cocaine and ATS.

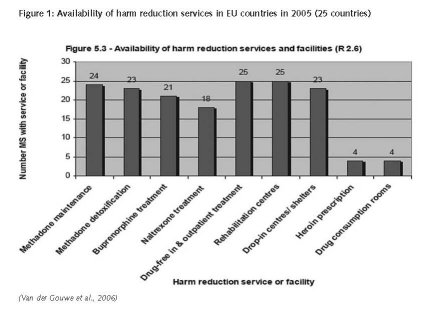

The figures on drug use-related harm, in the sense of health damage for the drug users, show again, in Western countries, relatively stable figures on the indicators selected (HIV infections and overdoses). The Netherlands, the United Kingdom and Sweden, but also the Czech Republic and Hungary, are examples of this. The latter two, together with Australia, are countries that have long had very low prevalence of HIV infection among drug users and with a falling number of overdoses deaths in the last decade. Interestingly enough, the Czech Republic and Hungary never experienced a real HIV epidemic. The annual growth rates of incidence and prevalence were always low. Recent prevalence rates (of IDU’s) are no more than 2.7% in the Czech Republic and 0% in Hungary. Also Turkey – for which reliable data are lacking– seems to be a country with low HIV prevalence rates among drug users. This may reflect the fact that (injecting) drug use started relatively late there and still seems to be limited.

Besides these countries with traditionally low HIV infection rates, some countries show a decrease in HIV infections among drug users. Brazil is one of these countries, though since there are no national surveys, this is based on some local studies in big cities (and prisons) showing that HIV prevalence among IDUs fell in some cities. Portugal is another example, showing both falling HIV prevalence among drug users and a decline in numbers of overdose deaths.

In those countries with low, stable or falling HIV and overdose prevalence rates, harm reduction is a part of drug policy, both officially and in terms of programmes implemented. Most of these countries have a relatively long tradition and broad geographic coverage of harm reduction programmes, having started syringe exchange programmes (SEP) and opiate substitution treatment (OST) at the latest by the mid-nineties. Exceptions are Brazil, where harm reduction started in the late nineties and still is mainly focused on HIV prevention, and Hungary, where harm reduction services do not cover all regions. Switzerland, now an active proponent of harm reduction (including heroin maintenance as well as safe injecting rooms and SEP), has a relatively high HIV rate among IDUs. This may be a consequence of the fact that the country adopted harm reduction after the heroin epidemic was well started.

Again, Canada is a partial exception. Despite introducing harm reduction programmes by the end of the eighties, problem drug use and drug use-related harm have been growing over the years. However, the latest data point in the direction of a change. According to data published by the Public Health Agency of Canada in 2008 the number of new HIV infections among IDUs appears to be decreasing overall in recent years.

Though the federal government of the United States firmly opposes harm reduction in international forums, there are many harm reduction programmes within the United States, reflecting the multiple levels of government (federal, state and local), as well as the very active and liberal philanthropic sector. SEP can be found in many cities, along with other interventions intended to encourage safer injecting practices. There are, however, no safe injecting facilities, and harm reduction programmes are not available everywhere.

The countries in our sample that are in the middle of a major transition process (China, India and the Russian Federation) seem to be confronted with a substantial rise of drug use-related harm. Though the figures are again weak – for the number of deaths by overdose we did not find any reliable data – available data point in the direction of a substantial increase in the number of drug users infected with HIV. In China the estimated number of HIV infected drug users went up from 12,536 in 1998 to 637,000 in 2007, though again there are substantial differences between available estimates. In India the number of new HIV infections increased over the past 10 years, but there are signs of stabilisation.

There are conflicting estimates of the number of drug-related HIV infections in the Russian Federation but overall the number of HIV infected drug users is reported to be high. According to information from the International Harm Reduction Association (IHRA) there are 2,000,000 IDUs in the Russian Federation, among which adult HIV prevalence is between 12 and 30%. Although the percentage of new HIV cases accounted for by IDUs is reported to have decreased from 95.6% in 2000 to 63.7% in 2007, the main route of HIV infection in Russia in 2006-2007 remained intravenous drug use.

3.2.3.2 Harmful consequences for society

The nature of harmful consequences for society differs widely across countries. It covers matters like crime linked to production, trafficking and retail/use (like violence, corruption and organised crime, but also drug use-related acquisitive crime, like shop-lifting, burglary and robbery) and public nuisance such as visible drug dealing and drug use in the streets, drug users congregating in the neighbourhood and discarded used syringes on the streets. In Latin-American countries the focus is on corruption and violence; in European countries on acquisitive crime and public nuisance.

Comparisons across countries are therefore difficult. The only relatively reliable data we have to hand is the number of drug law-related crimes. However, this clearly reflects decisions on the stringency of enforcement of drug prohibitions. Data on this indicator are available in a number of countries. Yet other forms of drug-related crimes might be more indicative of societal harm, for instance, so-called acquisitive crime or crime specifically linked to production, trafficking and selling. Data on these types of crime are never available on a systematic basis. Using the available data on drug law-related offences does not provide meaningful information for an assessment of drug-related harm for society. (Information on drug law-related offences can be found in the chapter on supply reduction.)

Drug-related harm is clearly a major problem to society for many countries; this is made clear in many different reports. Solid data on public nuisance are impossible to find; the only information available are narrative reports and expert judgement on whether the problem is substantial, comparing the 1998 and 2007 situation.

The Netherlands is one of the countries where public nuisance is perceived as a major element of the drugs problem. Since the late eighties it has become one of the key targets of drug policy to reduce drug-related public nuisance in neighbourhoods, i.e., drug users congregating and using drugs in the streets, dealing in the streets and drug use-related crimes like street robbery, shop-lifting and burglary. Another country where public nuisance is a prominent element of the drug problem is the United States of America.

A specifically Dutch problem is public nuisance caused by so-called drug tourism. The larger cities and those in the border region attract considerable numbers of young people from neighbouring countries (i.e., Belgium, Germany and France) who cross the border to buy cannabis in Dutch coffee shops. People living in the neighbourhood where these coffee shops are situated complain about crowds on the streets until very late in the evening, heavy car traffic and parking problems, etc. Consequently, initiatives have been taken on a local level to address this.

The disruptive impact of crime, violence, corruption and organised crime linked to drug production and trafficking cannot only be seen in Colombia, a country that is permeated by crime related to drug production and trafficking, and Mexico, where corruption is widespread and where the Northern states at the border of the United States suffer severely from drug related crime and violence caused by rivalry between drug syndicates (Goehsing, 2006); comparable information has been reported in South Africa, where the Italian Mafia, Russian criminal organisation, Chinese Triads and Nigerian syndicates play an important role in drug trafficking activities (UNODC, 2002; Shaw, 2002).

3.3 Drug policy

| • Drug policy papers convey little information on the actual implementation of policy; most are rather uniform with regards to supply and demand reduction objectives. • Across many countries criminal laws regarding supply are highly uniform concerning the substances classified as illicit, the acts defined as criminal offence and the ranking of the severity of drug-related crimes, i.e., considering production and trafficking as more serious offences than possession (of small quantities for personal use). • Demand reduction activities reflect widely-shared views of experts and support abstinence-oriented treatment and drug prevention. • Harm reduction is in some cases supported and in others impeded by legal provisions (e.g., not allowing OST); there is also growing agreement that harm reduction measures like OST and SEP are required to deal effectively with drug use-related harm. • Differences between countries in all three policy domains concern approaches, coverage and quality of the programmes realised. |

There is broad agreement among countries on key elements of drug policy. Viewing official drug policy papers – like drug strategies and drug action plans – reveals conformity with regards to aims of drug policy and measures to realise these aims. This is especially true for supply reduction and – to a lesser degree – for demand reduction, as will be illustrated below.

Yet, official drug policy papers do not really tell us a lot about policy measures actually implemented. Often these papers are, for the most part, political rhetoric based on ideological concepts rather than presenting a strategy to tackle the actual drug problem a country is facing. They are commonly formulated in general terms, striving for a ‘balanced and comprehensive’ approach to the drug problems.

Nearly all countries in our sample have in place formal drug strategies or action plans. This also holds true for most of the transitional countries included that generally have very comprehensive drug strategies. One diverging example is the Netherlands that, once in several years, – for example when a new government is installed – produces a general drug policy plan. When urgent problems require a formal policy response, policy papers on certain issues are produced on an ad hoc basis. In recent years this has been the case for Ecstasy and cannabis (Tweede Kamer, 2001 and 2004).

For that reason we decided to include in our analysis ‘official policy papers’, i.e. besides drug strategies and drug action plans, all governmental policy papers presenting objectives and plans for drug policy. In reviewing policy papers (and drug laws) we focused primarily on their coverage of the policy measures we selected as indicators in the three domains of supply reduction, demand reduction and harm reduction.

Drug laws also show considerable conformity in the majority of the countries. This is true for laws and legal regulations, among others:

• For the substances classified as illicit or legally controlled drugs (in many countries GHB was classified in recent years as an illicit drug);

• For the acts defined as a criminal offence, like production, trafficking, selling, possession, etc.;

• For ranking the severity of drug-related crimes, i.e., considering production and trafficking as more serious offences than possession (of small quantities for personal use).

The shared view that can be found in policy papers, in legal provisions and – to a lesser degree – in realised policy has, at least partly, to be explained by the quite intense international efforts to come to a uniform drug policy. International conventions, as for instance the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs (United Nations, 1961), the 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances (United Nations, 1993) and later additions to them, specify the substances that have to be brought under legal control and define what this control should entail, including exceptions to general rules and the measures to be taken against these substances. The origins of these treaties date back to the second decade of the twentieth century. Endorsing these international treaties and ensuring the implementation of their requirements is a prerequisite for being a member of the United Nations.

The EU is also working on a more uniform drug policy response especially in the field of supply reduction. One example is the European Council Framework Decision of 25 October 2004, laying down minimum provisions on the constituent elements of criminal acts and penalties in the field of illicit drug trafficking. This decision requires Member States to inflict standardized penalties for criminal acts linked to trafficking in drugs and precursors (Council of the European Union, 2004).

There are of course differences between countries, for instance in maximum penalties for drug law offences. The maximum penalty in China for possession of 50 or more grams of heroin is a death sentence. In most European countries one would face a maximum penalty of just some years of imprisonment for the same offence. Some countries apply minimum penalties for more severe drug law offences or in cases of recidivism. For instance, in the United Kingdom a more strict approach to trafficking offences was developed in recent years, including, among others, a minimum sentence of 7 years imprisonment for a third conviction for trafficking in Class A drugs. Other countries, for instance the Netherlands, oppose minimum penalties, because they seriously limit judicial discretion, i.e., the possibility to take into account particular circumstances of a specific offence.10 In some countries – e.g., in Sweden – drug use is defined as a criminal offence, in others – for instance in the United Kingdom – it is not. In recent years various countries have decriminalised drug use (see chapter on supply reduction).

There are more significant differences between countries with regards to the application of the laws. The implementation of drug laws in different countries shows that not all legal provisions have the same priority. In some countries the investigation and prosecution of offences involving cannabis are given less priority than offences related to opiates. In some countries this differentiation is based mainly on a tacit agreement, in others it is formal policy. The latter is, for instance, true for the Netherlands where the so-called discretionary principle “allows the Public Prosecution Service to waive criminal proceedings in the public interest. Law enforcement policy gives a high priority to large-scale trafficking in all kinds of drugs and dealing in hard drugs. Sale and possession of cannabis for personal use are much lower priorities. Details of these priorities are published in official guidelines. Dutch policy on law enforcement is therefore more explicit than in some other countries, which operate along the same lines in practice” (Available: http://www.om.nl/vast_menu_blok/english/verzamel/frequently_asked/what_are_the_main/, last accessed 21 January 2009). The guidelines include recommendations regarding the penalties to be imposed and priorities to be observed in investigating and prosecuting offences. Highest priority with regards to drug offences is given to large-scale production and international trade, lowest priority is possession for personal use. So-called hard drugs (opiates, cocaine and ATS) have higher priority than soft drugs (cannabis products) (Openbaar Ministerie, 2004).

However, certain principles are generally shared. There is, for instance, a universal agreement that drugs prohibition is an appropriate policy response to the drugs problem. This is the basis for the drug laws in all countries defining certain substances as illicit and stipulating measures against production, trafficking, selling and in many cases also the use of these listed drugs. There is also a widely shared understanding on which drugs should be listed in this law.

The drug law is one of the keystones of drug policy giving shape to and sanctioning policy choices. In particular drug supply reduction is firmly based on the provisions in drug law. Here one can also find the origin of many policy measures, which are common all over the world, not only in the countries studied. Examples are border control programmes to counter drug trafficking and drug squads to counter drug selling in the streets.

Yet, there are more legal provisions giving direction to drug policy. In some countries the implementation of policy papers is supported by legal means, e.g., the government in Portugal and Hungary specified by law how elements of the drug strategy should be implemented.

Legal provisions can stipulate, support or prohibit certain policy measures. One example for the latter is the Russian Federation, where methadone and buprenorphine treatment are prohibited by law. Also in India methadone treatment is ruled out by law. In other countries, such as Turkey, OST awaits legal approval from the government. In China harm reduction measures are being scaled up rapidly following the (legal) support offered by the authorities. Sometimes laws are formulated in such a way that one does not read the term harm reduction anywhere in the text, but the text itself supports or promotes some of these interventions. For instance, in 2003 the Russian State Duma (parliament) adopted a series of amendments to the Russian criminal code that included that “promotion of the use of relevant tools and equipment necessary for the use of narcotic and psychoactive substances, aimed at prevention of HIV infection and other dangerous diseases” did not violate the law, provided that it is implemented with the consent of relevant health and law enforcement authorities.

10 One regularly applied option to get around these limitations is to ‘go for’ an alternative, less severe offence in case the minimum penalty for the actual offence is considered too high.

Demand reduction and harm reduction policies are generally less well backed by legal provision than supply reduction. Still there is a widely shared consensus on the measures to be taken to reduce drug use. This consensus is at least partly – and in different countries to a different degree – supported by legal provision. Yet, in all policy documents on drug demand reduction of the countries in our sample we found emphasis on drug prevention and abstinence-oriented drug treatment as appropriate measures against drug use. Drug prevention, like school-based drug education programmes and mass media campaigns, can be found in nearly all countries. The same is true for abstinence-oriented drug treatment programmes.

However, this general consensus on which demand reduction measures are appropriate to tackle drug demand can be found in policy paper priorities rather than in practice. There are major differences between countries with regards to models / approaches chosen, coverage (investment, measurable as amount of expenditures) and quality of the programmes actually realised. In countries like the Netherlands and the United Kingdom short-term and out-patient forms of abstinence-oriented treatment are quite common. In other countries like the Russian Federation, long-term in-patient treatment is more prevalent. Western countries such as the United Kingdom, Australia and Switzerland have more diverse treatment programmes available and better geographical coverage of treatment services. In many of these countries quality assurance instruments are applied to enhance effectiveness and efficiency of treatment.

There is also growing agreement that harm reduction measures like OST and SEP are required to deal effectively with drug use-related harm. Still, there are some countries, which oppose the principle of harm reduction and/or certain measures. The federal government of the United States firmly opposes SEP; in the Russian Federation OST is banned by law.

Also in the field of supply reduction one can find major differences between countries with regards to approaches used, coverage and quality of the implemented programmes and the focus of measures taken. For instance, border control measures can focus on international traffic hubs like airports and harbours or on tracing trafficking routes. These differences also reflect differences between countries with regards to the nature and extent to which they are affected by supply problems. In countries playing a major role in the production of certain drugs, the features and extent of drug production have an influence on the priorities set and measures taken. In Colombia, the major coca producing country in the world, crop substitution programmes and spraying of coca fields are important measures. In the Netherlands, a major Ecstasy-producing country, measures to control production and handling of precursors are a policy priority as well as dismantling Ecstasy laboratories.

Many factors apart from the socio-economic situation and the nature and extent of drug problems, contribute to the formation of a nation’s drug policies. It often fits into a broader political agenda. Notably in the United States in the 1980s the alarming rise in homicides, only partly related to drug use and distribution, gave a harsh tinge to responses to the growing problem with crack. Recent tightening of drug policy in the Netherlands (e.g. restricting the number of coffee shops) is part of a broader wave of conservatism in social policy.

Expenditures

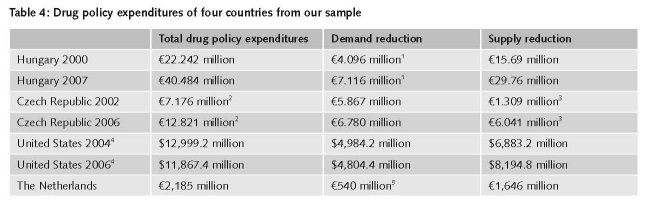

| • Drug policy expenditures in many countries increased significantly in the past decade. The biggest share of the budget is spent on supply reduction. |

It was our intention also to include data on drug policy expenditures in our discussion of differences and communalities of drug policy in the selected countries. This would allow assessment and comparison of investment in the three policy domains and the different policy measures taken. However, reliable data on drug policy expenditures are rather rare. In some countries specified drug expenditure data are non-existent. In many countries these data (if available) cover drug policy budgets in general, and don’t disaggregate these into budgets per drug policy domain, let alone into specific drug policy measures like drug treatment or drug prevention.

Also in many countries with relatively solid monitoring of drug problems and policy, as in most of the EU Member States, there are no good data on drug policy expenditures, not even for the specifically labelled drug-related expenditures. Therefore we limit ourselves to a discussion of some basic features of drug policy expenditures discernible from the available data and experts’ opinions, e.g., on the share of budget made available for the three drug policy domains.

Many countries in our sample report that drug policy expenditures increased significantly in the last decade. This is true for, among others, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Portugal, India and the United States. Yet detailed figures are available for very few countries. India, for instance, does not have data on national drug policy expenditures but experts assess the spending on supply reduction as much higher than on demand reduction. More detailed information can be found in the national reports of the Czech Republic and Hungary presented to the EMCDDA and in reports on the United States and the Netherlands (see table 4 below).

1. Figure includes expenditures for treatment, harm reduction and other social care.

2. National/federal budget (i.e. not including local/state budgets).

3. Not including the expenditures for the national drug squad which increased from €3,395,000 in 2003

(2002 figures are not available) to €3,757,000.

4. These figures show the executed budget and only include federal expenditures and exclude some

major items, in particular the costs of prosecution and imprisonment. It is usually assumed that

state and local governments spend as much as the federal government. Total national expenditures,

dominated by enforcement, are probably around $35 billion.

5. Figure includes expenditures for prevention, treatment and harm reduction.

In all countries where we found information on drug policy expenditures – from actual calculations to rough estimates – the biggest share of the budget is spent on drug supply reduction. For Australia it is stated that the majority of expenditure is enforcement-related, while harm reduction accounted for only 2% of policy spending. Still, in the National Drug Strategy 2004-2009 it is stated that, since its inception, the basis of drug policy is harm minimisation, i.e., a balanced approach including demand reduction, supply reduction and harm reduction.

3.3.1 Supply reduction

| • Many countries show a trend to a more tough, punitive approach to production and trafficking and at the same time a more lenient, health-oriented approach to use and possession of small quantities for personal use. • Developing and transitional countries are following this trend. |

For supply reduction, involving measures against production, trafficking and retail, we selected seizure data (number of seizures and quantities seized) and data on arrests for drug law-related offences as indicators. These data are available for many countries, but they do not always specify the substances involved and the underlying offence, e.g., whether it is related to production, trafficking, dealing or consumption. We also looked into imprisonment figures for drug law-related offences. Yet only in (some) Western countries are these data collected systematically, and specific information on the underlying offences is even more rare. Of course, here one also has to take into account the differences in methods and quality of data collection in different countries mentioned in earlier chapters. Where possible we singled out data for arrests for drug use and possession of small quantities for personal use, as there are countries where drug use as such is not regarded as a criminal offence.

There are hardly any quantitative data on specific measures taken against production, trafficking and retail. Comparing production countries with regards to measures taken does not make much sense as one would have to take into account the extent of the production, the differences between the production of the four substances studies (how to compare crop eradication against coca cultivation with dismantling laboratories targeting Ecstasy production), country specifics (e.g. densely populated, urban vs. unpopulated, rural), the budget available and the effectiveness/efficiency and quality of the measures taken. Also for trafficking (and retail) comparable information on the measures taken is unavailable. Hence, we decided to confine ourselves to giving some narrative account and analysis of measures taken, based on available reports and expert judgement.

3.3.1.1 Policy priorities

Policy documents from the majority of countries in our sample show that there is general agreement on the key issues of drug supply reduction. In almost all countries the fight against production, trafficking, dealing and, in a number of cases, also consumption of illicit drugs is considered a priority. Examination of reports from international bodies and organisations like UNODC and EMCDDA supports this impression for countries other than those in our sample. This may be just rhetoric in part but aside from statements in policy papers one can identify in some countries a trend towards putting more effort into fighting production and trafficking and to tightening the drug law provisions, in particular against trafficking. One of the countries choosing a more strict approach to trafficking offences is the United Kingdom, including a minimum penalty for a third conviction for trafficking in Class A drugs and a maximum penalty of life imprisonment for trafficking in Class A drugs, while trafficking of Class B and C drugs can attract a penalty of up to 14 years in prison. Besides the decision to have tougher legal provisions, seizure and arrest figures and, where available, data on expenditure, prove that countries invest substantial amounts of money in supply reduction. In countries where we found information on drug policy expenditures, the largest part of the budget is allocated to drug supply reduction (see table 4).

Along with this trend towards a more punitive approach to production, trafficking and dealing, one can see a moderation in the policy towards use and the possession of small quantities for personal use. In several countries drug use is no longer listed as an offence in drug law. In the Netherlands and the United Kingdom this law change was introduced in the seventies. The United Kingdom Misuse of Drugs Act of 1971 states that drug use per se is not an offence but it is the possession of the drug, which constitutes an offence. As in the Netherlands the severity of penalties for the unlawful possession of drugs differs per type of drug. In the United Kingdom possession of Class A drugs such as heroin or cocaine is punished more severely than possession of a Class B or C drug. In countries like the Czech Republic and Portugal, decriminalisation of drug use has been introduced into drug law in the past decade.

In Portugal the drug law change in 2001 included decriminalising illicit drug use but maintains drug use as illicit behaviour. However, for a person caught in possession of a quantity of drugs for personal use (established by law), sanctions can be applied, but the main objective is to explore the need for treatment and to promote recovery. This health- rather than penalty-oriented attitude towards possession of small quantities can also be found in the countries, which opted for fully decriminalising consumption. Where penalties are applied they are generally administrative sanctions (a fine or warning) as for instance in the Czech Republic.

Transitional and developing countries have started to follow this line. The Russian Federation, Brazil, Mexico and India have all reduced penalties for consumption and possession of small quantities for personal use. In the Russian Federation the use of drugs is only an administrative offence since 2004. In Brazil the political decision to change the law in favour of a less strict approach to possession of small quantities seems to lack support by the judiciary system. We received reports that courts still adhere to a tougher approach.

3.3.1.2 Seizures

We have already dealt with seizures as an indicator for trafficking. However, number and quantities of seizures, being outcomes of measures taken against production, trafficking and retail, are more powerful indicators for supply reduction measures. Still, the limitations mentioned earlier should be borne in mind.

The chapter on supply made clear that there are major differences between countries with regard to drugs seizures. This is due to different factors like the specifics of the drug problem in a particular country, whether it has a trafficking rather than a consumption problem, what drugs are used in the country, etc. Yet, when using seizures as an indicator for supply reduction measures one obtains a less confusing picture. Number of seizures and quantities seized mirror relatively well the drug supply reduction policy efforts in a country. Seizure data underpin that in the past decade different countries put more effort in bringing down production and in particular trafficking.

In many countries drug seizures have increased in recent years. We already mentioned Brazil and Turkey in the drug supply chapter. The United Kingdom is another example where, in particular, an increase of heroin, cocaine and Ecstasy seizures (in number of seizures and quantities seized) has been reported for the period from 1998 to 2004. In Portugal the increase of seized quantities of cocaine might reflect the prioritising of measures against cocaine transhipment from Western African countries to other countries in Europe. In Hungary the number of seizures of heroin, cocaine and amphetamines has been increasing continuously in recent years (till 2006).

3.3.1.3 Drug-law offences and arrests

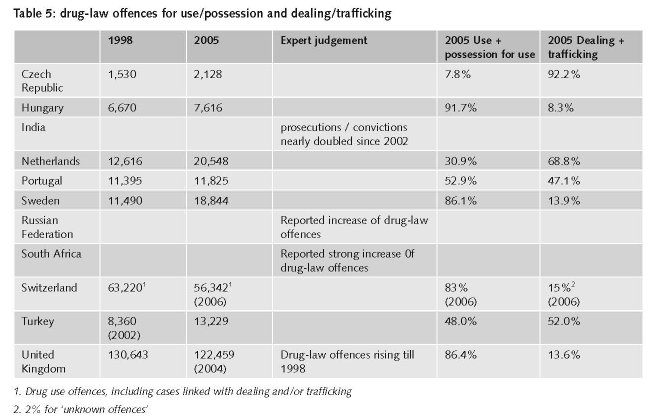

| • The majority of arrests in most countries are related to use and possession. • The biggest share of drug law arrests is related to cannabis offences. |

The increasing number of drug law-related arrests in several countries gives strength to the impression that supply reduction measures gained priority in recent years. This trend can be identified in Western and in transitional countries. In Canada drug arrest rates reached an all-time high in 2002. In many EU countries drug law offences rose in the past decade. Also for transitional countries like the Russian Federation, China and India one finds reports of a rise in numbers of arrests.

There are of course many factors possibly contributing to raising arrest numbers. In countries like India and the Russian Federation the growing market might lead to an increase in efforts. In Turkey increasing arrest figures might reflect the adaptation to EU drug policy priorities as part of the preparations to accede to the EU.

There are countries diverging from this trend of growing arrest numbers. In Portugal the figures seem to be pretty stable.

The United Kingdom even reports a falling trend.

Yet there is more to say about these trends. For the countries specifying their arrest data the bulk of arrests is related to use and possession. Again there are diverging countries like Czech Republic, the Netherlands and Portugal (see table 5 below).