Report 4 Approach

| Reports - A Report on Global Illicit Drugs Markets 1998-2007 |

Drug Abuse

2 Approach

This report, like the others in this volume, focuses on four drugs in detail: cannabis, cocaine, heroin, and amphetamine-type stimulants (ATS). In some nations other drugs are also widely used but they either contribute little to the total global market for illicit drugs or are not the subject of much explicit policy making. For example, the sniffing of substances by adolescents is common in countries as varied as Scotland and Mexico; however little is known about this phenomenon in terms of prevalence, for instance and there are few interventions targeted at users of these substances. In the national studies such phenomena will be noted, but types of drugs other than the four mentioned above will not be systematically studied on a global level.

We have taken countries as the unit of analysis. Policy is made at national level, or lower, and different parts of the world are very heterogeneous. For example, Canada has a very different, and much smaller, drug problem from that of its neighbour, the United States. It also has a different drug policy, which has undergone substantial changes over the last decade. Therefore we will focus on an assessment of how the illicit drugs phenomenon has developed globally, and in the most affected countries, in the past decade, and also on how these developments can be explained.

2.1 Selection of countries

In order to provide as full a picture of the changes in drug problems and drug policies around the world as possible, we have selected eighteen countries. In order to select countries with varying profiles we employed the following criteria:

• Coverage of all regions of the globe;

• Inclusion of countries that vary substantially with regards to the nature of the drugs problem they face (production, trafficking and use) and which reflect differences in the evolution of the drugs problem between 1998 and 2007;

• Inclusion of countries differing in drug policy choices and development in the past decade;

• Coverage of countries differing with regards to socio-economic development.

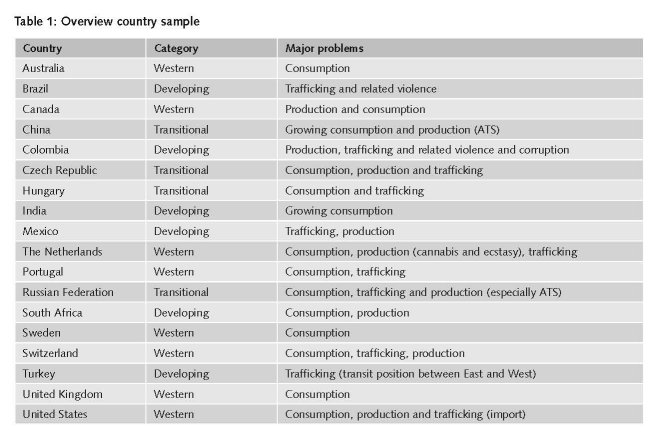

In Table 1, we present a very brief assessment of the principal drug related problems of the 18 countries that we studied, simply to illustrate their variety. These assessments are intended as rough judgments rather than nuanced statements. Countries rarely present “pure” cases. For example, Mexico does have some problems of drug consumption, e.g. marihuana and cocaine, while India does have some illicit poppy cultivation. However these judgments do provide an indication of what problems the government in each nation is most likely to target in its policy decisions.

The countries fell into two categories; those that could essentially be studied through desk research, including phone interviews with selected key experts (i.e., Australia, Canada, Czech Republic, Hungary, the Netherlands, Portugal, South Africa, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States) and other countries where it was considered necessary to conduct country visits to collect as much data as possible for our study (i.e., Brazil, China, Colombia, India, Mexico, Russia and Turkey). We distinguished between so-called Western, developing and transitional countries (see Table 1). Western refers both to a cultural identity and to a high level of wealth. Some nations could clearly be placed in more than one category. For this sample of countries we produced reports describing the drugs problem and drug policy and developments in the past decade for each country. These country reports can be found in the Appendix of this report.

For the desk research countries we drew on existing sources through the internet and available literature to provide a systematic description of drug problems between 1998 and 2007 (depending on which is the most recent available year, also taking into account comparability between countries). We contacted a number of local experts by phone and by email. We also liaised with experts from the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) who, as well as offering valuable data on the topics of interest, had considerable experience in data cleaning and quality control for each of the indicators that they are responsible for. The EMCDDA proved to be a particularly valuable source of information and expertise for our purposes. Measuring the extent of a nation’s drug problem required adaptation to the vagaries and heterogeneity of national collection. For example, the United States does not measure the number of problem drug users, a central construct for the EMCDDA, but instead has a series, not updated since 2000, for chronic users of each of cocaine, heroin and methamphetamine (ONDCP, 2001) (see also report 6 on methodological challenges).

Conversely, many developing and transitional countries do not have high quality data. As with many countries on the list, the existing data were scant and of poor quality. We therefore worked with a selection of local experts to supplement what is available officially and in published literature. Given the limited expertise and indicators available in many of these countries, particular care was given to the triangulation of both expert opinion and indicators.

2.2 Selecting indicators

Drug problems involve many diverse issues, with an emphasis on problematic forms of drug use, drug use-related morbidity and mortality, social problems in neighbourhoods caused by drug-related crime and public nuisance, and criminal activities linked to the illicit drugs market. Therefore the policy response to these problems is an inherently intersectoral activity involving, at a minimum, health, social, criminal justice and educational agencies to be effective. It is the sum of laws and programmes and is described not merely by the stated policies and related expenditures but by how it is implemented. Thus a major task of the project was to develop a parsimonious set of indicators that would characterize the nature and severity of the drug problems in a country and would also highlight the differences in drug policy.

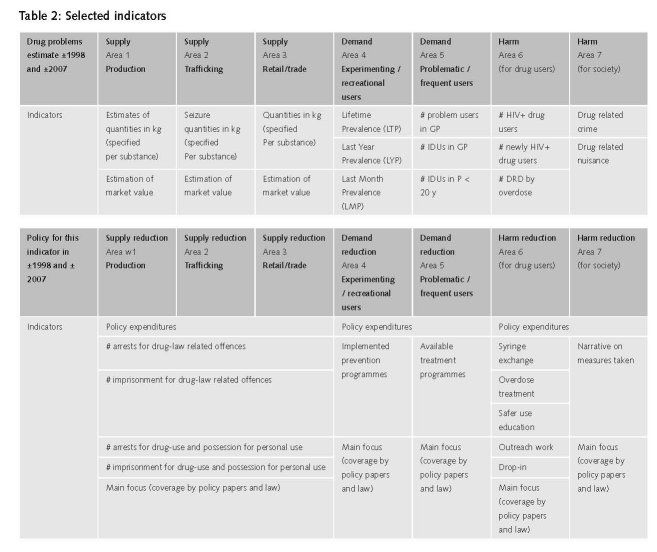

We developed a set of indicators, one sub-set to assess the drug problems (supply, consumption (demand) and harm) and another sub-set to assess drug policy in the selected countries (supply reduction, demand reduction and harm reduction). We subdivided these domains of drug problems into seven areas. Under supply we differentiated between production, trafficking and retail; under demand, between experimental or recreational use and problematic or chronic use; and under harm, between drug-related harm for the users and harm for their surroundings.

It was difficult to strike a reasonable balance between selecting sufficient indicators to give us a thorough insight into drug problems and drug policy, and the need to limit the number of indicators (due to limited time and resources, as well as the limited availability of data on many relevant issues). We used the following questions to select the indicators:

• What information do we need to characterize the drug problems and drug policy in a country?

• What indicators provide pertinent information on drug problems and drug policies?

• Are there appropriate data sources available for a certain indicator?

• What indicators are available and have been used throughout the last 10 years?

• What data/information on these indicators is available on the current situation and on that of ten years ago?

The indicators selected to characterise drug problems should obviously match with the indicators selected to describe drug policy. For instance, selecting the number of HIV- infected drug users as indicator for drug-related harm resulted in selecting HIV prevention as a drug policy indicator. In table 2 we present an overview of the selected indicators.

We aimed to compile a set of indicators that would allow the comparison of drug problems and drug policy in a single country and also between countries within the past decade, based on stable definitions over time and data collection at regular intervals. Where possible we built on the work already done by EMCDDA, UNDCP/UNODC and other data collectors to standardise the collection of monitoring data. We are aware that these international data collections have their limitations. The most robust are the EMCDDA data as they are systematically collected, evaluated, commented and reported. Still they also have some limitations (see also report 6 on methodological challenges). For instance, there have been some changes in the EMCDDA data collection system during the past years but these have been minor changes.1 Therefore we decided to take the EMCDDA data at face value for the country reports of the EU Member States (Czech Republic, Hungary, The Netherlands, Portugal, Sweden and the United Kingdom).

For some other countries we could use high quality research data from, among others, household or school surveys. This was the case for Australia, Canada, Switzerland and the United States. In these cases the methods are briefly characterised for the reader.

For countries where there were no such studies, we used data from reports of international organisations, mainly from the UNODC (in particular World Drug Reports and the 2008 Global ATS Assessment), UNAIDS, the OAS/CICAD (mainly for South American countries) or the 2008 International Harm Reduction Association (IHRA) report on the global state of harm reduction. Many of these reports depend on primary research in separate countries, on data collection of lesser quality (e.g. largely based on systematic questionnaire research in countries around the world such as the Annual Research Questionnaire of the UNODC (ARQ) on drug problems and the Bi-annual Report Questionnaire (BRQ) on activities to reduce drug problems) or expert judgment (e.g. data collection via governmental agencies). For many countries the data from these reports are the best available at this moment (see report 6 on methodological challenges).

Finally, where no data were reported, expert judgement was the best we could obtain.

2.3 Data collection by questionnaire

We used the set of indicators to develop a questionnaire with a number of questions per selected indicator. This questionnaire was used both for desk research, to examine relevant literature on all 18 countries, and the actual interviews (by phone or mail with selected key experts in the desk research countries, face to face in the visited countries). Where possible we checked information by using different sources. The data collected served as basis for writing the country reports.

1 Examples are the data collection on syringe availability (Standard Table 10) and on drug treatment (standard questionnaire 27) which has recently been divided into two parts, one on treatment programmes and one on treatment quality.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|