Report 3 Determining the unit cost of drug-related harms

| Reports - A Report on Global Illicit Drugs Markets 1998-2007 |

Drug Abuse

5 Determining the unit cost of drug-related harms

A significant challenge when trying to compare the economic cost of any health related behaviour across multiple countries is the development of consistent unit cost estimates. Health care systems differ, which impact the average cost of services received and who pays for those services. Further, labour markets differ, which impacts the average cost of a lost day of employment as an individual’s wage may or may not be a good measure of the average productivity at work. Added to that in the case of using an illicit drug is the additional challenge of trying to prevent use of an illegal substance. The difficulty is not just in terms of thinking how one might want to measure these average costs, but also in actually obtaining reasonably good data of those costs you are trying to capture. Herein lies the greatest challenge.

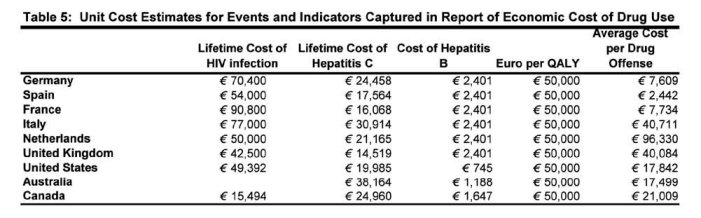

Table 5 provides a summary by country of unit cost estimates that might be applied to calculate the total cost of drug use for the some of the indicators constructed thus far. As was the case with the actual indicators of harm, going through the exercise of identifying the source for potential unit cost estimates makes explicit the pitfalls and issues involved in trying to construct these estimates. To the extent possible, the unit cost estimates represent the average costs of particular events, and have all been adjusted and/or inflated to reflect 2006 Euros.16 In many cases the method for obtaining the unit cost estimate for a particular event differs across country. To the best of our ability, we attempt to keep the unit cost estimates homogeneous with respect to the resources used to manage an event. It is not possible in all cases to cost an event in the exact same fashion, however. Differences in approaches and resources included in particular unit cost estimates are discussed in greater detail below.

5.1 Estimates of the lifetime medical cost of HIV infection

Estimating the average cost of treating HIV over the probable disease states across countries is particularly difficult as transition rates to various stages of the disease could differ substantially across countries as well as the therapies applied in any given disease state. Given the difficulty in trying to consider these aspects, we rely on estimates generated in previous work by Postma et al. (2001), who estimate in 1995 dollars that the lifetime costs of HIV infection for 10 European countries varied from €42,500 to €90,800 (UK = €42,500; France = €90,800; Italy = €77,000; Netherlands = €50,000; and Spain = €54,000) 17. It is clear that the typical treatments (and hence the cost of these treatments) have changed substantially since 1995, the year in which this study estimates lifetime costs. Indeed, one study using a sample of patients in Alberta Canada reports that in 1995 the cost of antiretroviral drugs accounted for 30% of the cost per treated patient per month. In 2001, they accounted for 69% of the cost per treated patient per month due largely to the widespread use of HAART (Krentz et al., 2003). Nonetheless, the Postma study takes the very important step of considering the mix of specific therapies used at various stages of the disease by country in the construction of their estimates, which represents to us a very important step for ensuring that the cost estimates are truly reflective of the cost of treatment overall.

In an effort to construct unit cost estimates for non-European countries in a fashion that is medically consistent with estimates reported by Postma et al. (2001) for Europe, we use a somewhat dated estimate of the cost of HIV reported by Zaric et al. (2000) to approximate the average lifetime cost of treating HIV in the United States. Zaric et al. (2000) report the average cost of treating HIV among injection drug users in 1998, which we inflate to 2006 dollars and convert to Euros. Information on the cost of treating HIV infection over its life course in Canada come from an Alberta study providing estimates for 1999 (Krentz et al., 2003). We were unable to obtain an estimate of the lifetime cost for the same general period for Australia (using a more current estimate would reflect improved medicines and make the comparison inconsistent).

5.2 Estimates of the lifetime medical cost of hepatitis C

Hepatitis C is typically identified through an evaluation of liver functions or when someone goes to donate blood. As such, it usually goes undetected until the advanced stages of liver disease have occurred, and by that time treatment is less effective and liver transplants are required or the patient will die. According to Wong (2006) combination therapy with ribavirin and pegylated interferon has improved the chances of people not progressing to later stages of the disease, although Wong notes that not all untreated individuals progress to develop cirrhosis and not all treated individuals are responsive to treatment. According to research using blood donor and community cohort samples, 14-45% of patients resolve their acute HCV infection while about 1-10% develop cirrhosis within 20 years of identification of the disease (Freeman et al., 2001; Seeff, 2002).

Information on the lifetime cost of HCV among drug users in Europe comes from a recent study by Postma et al. (2004), who attempt to estimate the lifetime costs per hepatitis C infection after introduction of HCV combination therapy. They update an earlier estimate of the lifetime cost of HCV in drug users in 10 European countries using a French Markov model that incorporates the progression of HCV disease in infected blood donors through pharmacotherapy, active HCV infection, cirrhosis, decompensated cirrhosis, transplantation and death. The disease progression model is based on Loubiere et al., (2001). The model distinguishes two phases of the disease. In the first phase (the first 1.5 years of contraction) patients are merely distributed over two stages of “recovery” and “active HCV”, which is treated mainly with pharmacotherapy. Only after the first 1.5 years to the Markovian annual transition rates into alternative phases of the disease take place, and they are not deterministic but probabilistic. The model allows for the combination of treatment (or re-treatment) with interferon and ribavirin with 40 to 50% success rate. The model is applied to a drug user diagnosed with HCV at the age of 25 (a fairly young age) and unit cost estimates for each stage of the disease are applied using information that is available for France (in 1999 Euros) when other country-specific estimates of the cost of each of these disease-stages are not available. The country-specific estimates come from Figure 4 (p 211) and are updated to 2006 Euro (from 1999). In 1999, the estimates by country were as follows: France = €14,140; Germany = €22,000; Italy = €26,200; Spain = €14,000; UK = €13,100. The updated study did not re-estimate costs for the Netherlands, which were included in the earlier study, but because were unable to find a comparable updated cost we use the estimate from the Postma et al. (2001) study.

In the case of hepatitis C, there appears to be far more convergence regarding methods for costing out the lifetime cost of the disease, as sources were identified for each of the non-European countries that used the epidemiological model for costing out the average burden of the disease. Saadany et al. (2005) use a Markov model to predict the progression of disease for individuals suffering with hepatitis C for the population of Canada from 2001 to 2040 so as to construct estimates of the annualized economic burden of the disease. We use their estimate of CAN $14,312 to represent the average cost of the first year of the disease.18 For the U.S., we use the median value of a range of estimates reported by Wong (2006) of the average wholesale price of 24 weeks of ribavirin and interferon in 1999 (assuming full compliance) to be between US $9200 and $17,612. For Australia, we use estimates from Shell & Law (2001) who estimate the lifetime discounted cost associated with each new case of HCV infection in Australia to be AUS $19,100.

5.3 Estimated cost of hepatitis B

Estimates of the average cost of treating hepatitis B by disease state for each European country were reviewed and summarized in a recent study by Brown et al. (2004). According to their study, the average cost of treatment increases with the progression of the disease and is indicated by progressively more costly disease states in 2001 Euros. Given that the estimates of the prevalence of hepatitis B were generally based on blood tests indicating the virus is present in the bloodstream rather than any more advance state of the disease, and given that the disease has become highly more manageable with pharmacotherapies, we use the median value of the range of estimates provided for Chronic Hepatitis B (CHB) treatment in Europe, given by €2245 in 2001 (average cost of CHB, €1,093- €3,396). We focus on the cost of this treatment alone, as it is something that can be consistently estimated for each of the non-European countries (and again, the disease has become far more manageable when diagnosed in the early stages). For Canada, we use an estimate of the pharmacotherapy cost of CHB treatment from Gagnon, Levy et al. (2004) and inflate this to 2006 Euros. Butler (2006) provides a comparable estimate for Australia in 2004 dollars, which we also inflate to 2006 Euros. In this case, it is the United States for which we do not have a good comparable unit cost estimate.

5.4 The intangible costs of addiction: Euro per QALY

Like any other health problem, addiction and drug dependence reduce the quality of life of those suffering from the condition, independent of its potential effects on productivity, employment, or health service utilization. Health improvements (recovery from addiction) translate into direct welfare gains for those affected by the illness as well as indirect gains for those who care for or live with the individuals afflicted. It is difficult to place a monetary value on the burden addiction places on those affected by the disease as well as their family and caregivers, but failing to do so significantly underestimates the full burden of the disease. A number of methods have been used to try to quantify the loss in well-being associated with various health conditions, including cancer, multiple sclerosis, liver disease, hypertension, and HIV/AIDS. One of the more common approaches used in health services literature today is the quality-adjusted life years (QALYs)19 technique.

The QALY approach presumes that the impact of health problems on the overall quality of life can be quantified through trade-offs that people would be willing to make between alternative health states they might live with, given variations in the length of time they would live with each. Several generic health state classification systems, such as the EuroQol, SF-36, MILQ, and the Quality of Well-Being Scale, have been developed by researchers to assist in the translation of health functioning into numerical scales (Drummond et al., 1986; Ware, 1994; Gold et al., 1996; Avis et al., 1996). Pyne et al. (2008) compare two generic preference-weighted measures for substance abuse disorders specifically to assess the burden addiction places on well-being. They examine the QWB-SA and the SF-12-SF and find that in a general population including individuals with substance use disorders that those suffering with a lifetime substance use disorder and currently experiencing symptoms have a reduction in well-being of 0.126 and 0.141 depending on which preference-weighted index was used (Pyne et al., 2008). In their study of the cost-effectiveness of expanding methadone maintenance treatment for heroin addiction, Zaric et al., (2000) find that a change in substance use behaviour is associated with a 0.2 change in QALY. The higher value is likely to be driven by the stronger association to HIV that was drawn by the population in the later study.

Given that the difference in QALYs suggested by Pyne et al. (2008) are fairly small, it suggests that differences in lost QALYs associated with drug addiction are likely to be less sensitive to the choice of preference-weighted scale and more sensitive to the population being surveyed (e.g. full population versus just a population of heroin users). Taking this into consideration, we attempt to assess the intangible burden of addiction by assuming that individuals living with addiction experience a reduction in the QALY of 0.14 per dependent user.

According to a comprehensive literature review and analysis by Hirth et al. (2008), there is tremendous variation in the estimates available in the literature on the dollar (or euro) value of a QALY and nothing close to a consensus has developed. 20 However, interventions are often assessed assuming a value of €50,000 per QALY (Drummond et al., 2006). If we assume the reduction in QALY is the same regardless of where a person is living, we can use the estimated reduction in QALY (0.14) and multiply it by this monetary value per QALY (€50,000) to generate an estimate of the intangible cost of living with addiction in a given year.

5.5 Cost of law enforcement for drug offenses

No information is readily available from most countries regarding the marginal cost of arresting, processing and adjudicating drug offenders.21 Thus, one is left only with the option of constructing an average cost estimate using a top-down approach using information on law enforcement budgets and the number of offenders going through the system. This is a common approach used in numerous national studies (e.g. Collins & Lapsley, 2008; Rehm et al., 2006). The key assumption underlying this approach is that the amount of resources used in arresting, processing and adjudicating a drug offender is the same as that for any other offender (whether violent offenders or nonviolent offenders). Clearly, such an assumption is problematic. Nonetheless, without more sophisticated data systems tracking the cost of processing specific cases in each country, no other method can be implemented.

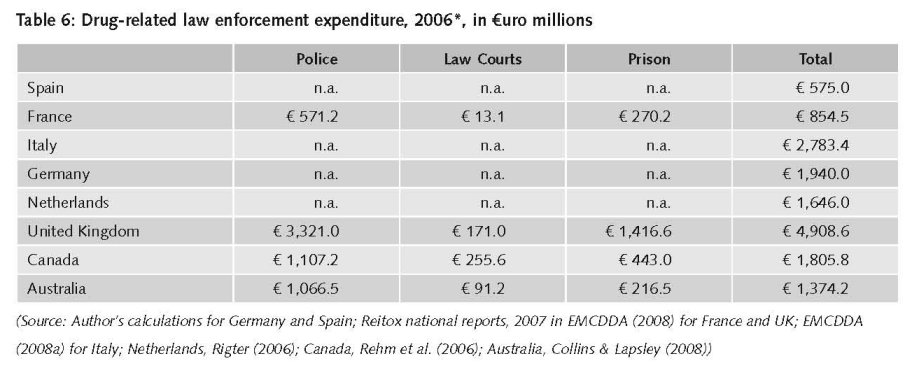

To begin, one must identify the fraction of expenditure from each country that is spent enforcing drug laws. Even in the European Community, where expenditure data are more consistently reported across countries using the international “Classifications of the Functions of Government”, or COFOG, system, information on drug-specific enforcement expenditure is not readily available for all countries. Recently, some European countries have taken the initiative to collect drug-related expenditure data utilizing the COFOG system and report this information as part of their REITOX reports. These figures are reported to the EMCDDA in two forms- labelled and non-labelled. Labelled refers to planned expenditure explicitly marked in budget and/or fiscal year end accountancy reports. According to EMCDDA, these labelled expenditures do not tell the full story since “not all drug-related expenditure is identified as such in national budgets or year-end reports” (EMCDDA, 2008). In addition, the non-labelled approach is similar to the methods employed by countries outside of Europe (particularly Australia and Canada). Therefore, the non-labelled expenditures are a more realistic measure of expenditure data and are what we use here. The non-labelled data are derived from an estimation procedure referred to as a ‘gross (or top-down) costing approach’. This consists of identifying the total amount of the budget in a given area (i.e. Public Order and Safety) and then determining the proportion of that area which is drug-related. The strategies for estimating these proportions vary quite substantially across countries, making direct comparisons of figures inappropriate (EMCDDA, 2008).

The UK provides a very rigorous estimation approach (in Euros) of all drug-related expenditure, including law enforcement, as part of its National Focal Report to EMCDDA, which partially explains why its figures exceed those of other countries in most drug expenditure categories (EMCDDA, 2008). The Netherlands, on the other hand, produce a single report (Rigter, 2006) using the top-down approach and includes it as official data in its annual report. Italy provides the overall social costs to the drug problem and the proportion devoted to law enforcement with little explanation of the definitions (EMCDDA, 2008a). Two countries, Germany and Spain, do not provide sufficient information for understanding where the amounts come from. Germany provides estimates of non-labelled law enforcement expenditure of €36 billion, with no indication as to the proportion devoted to drugs (National Focal Report 2007). Spain simply provides a rough estimate for overall public expenditure related to the drug problem, €400 million; however, no information is provided on the proportion devoted to law enforcement (EMCDDA, 2008a). Thus, we estimate figures for Spain and Germany based on 1999 estimates of the proportion of drug-related law enforcement expenditures as 0.083% and 0.059% of GDP for Germany and Spain, respectively (Kopp et al., 2003). Using these proportions for 2006 GDP data22, we find €575 million and €1,940 million on drug-related law enforcement expenditures.

Although not part of the EU reporting system, the estimates for Australia and Canada are calculated through a similar top-down procedure. Australian data utilizes an updated set of fractions for drug-related crimes from the Australian Institute for Criminology and cost data from the Steering Committee for the Review of Commonwealth/State Service Provision (Collins & Lapsley, 2008). Canadian data on drug-related law enforcement expenditure is developed from surveys of the prison population on proportions of criminal activity involving drugs and expenditure data from government sources (Rehm et al., 2006).

The following table displays the drug-related law enforcement expenditures for all countries except the United States, whose estimate is done in a somewhat different fashion and will be discussed shortly. The expenditure data is for 2006, except for the Netherlands which is for 2003. For Canada and Australia, the figures are 2006 adjusted for inflation using national statistics databases for CPI data and converted to Euros using European Central Bank data based on 01/07/2006 exchange rate.

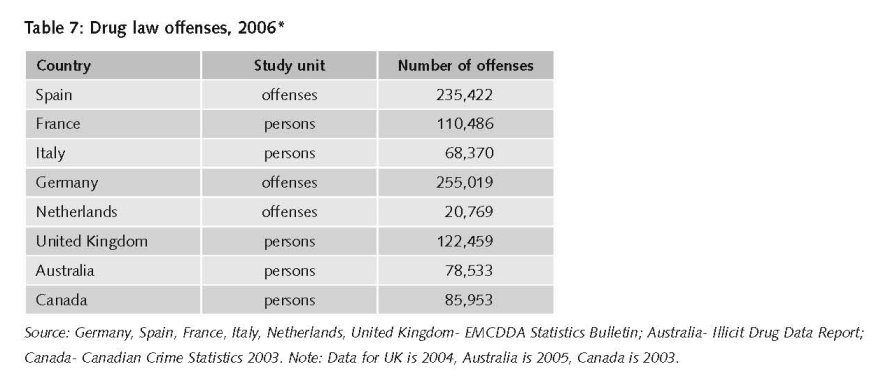

To convert these estimates into unit costs, we need a measure of the total number of drug offenders going through the system in each country. Drug activities that are considered unlawful offenses vary across countries. Generally, drug law offenses refer to producing, trafficking, dealing, possessing or using illicit drugs. Table 7 presents the total number of reports for drug offenses by country. The data has been reported and documented at various stages within the criminal justice system (by police, courts, or prison personnel).

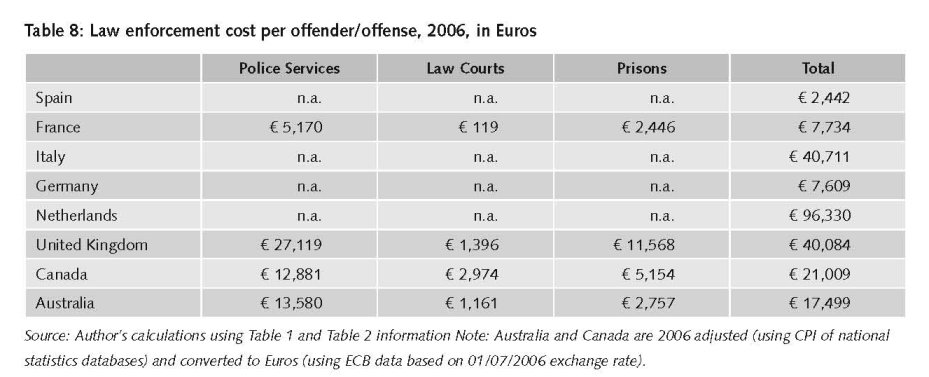

By dividing total drug-related law enforcement expenditure by the number of drug offenders being processed through the system, one can generate a unit cost estimate of the average cost of a drug related offense, which we do in Table 8. As can be seen in that table, unit costs vary greatly across countries since the countries have different costing procedures and offenses definitions. Italy and the UK have virtually the same unit costs of approximately €40,000 per offender per year. Although France has similar offender rates as the UK, total costs are much lower and thus, the total unit cost in France is €7,734. Canada and Australia exhibit similar total unit costs for drug enforcement of approximately €20,500 and €17,500, respectively.

Results indicate court costs per drug offender are the lowest costs and policing per offender are the greatest costs for all countries. Although it is problematic to compare across countries, it is interesting to note that while total unit costs in the UK are nearly twice the amount of that in Australia, the court costs are nearly identical. Comparing Canada and Australia, which have similar total unit costs, Canada spends more per unit on prisons and Australia spends more on policing. Another potentially interesting comparison is between France and Australia in which Australia has a total unit cost more than double that of France and yet both France and Australia have similar prison unit costs.

As noted previously, the estimate of the average unit cost of an arrest for the United States is actually constructed in a different manner, using information provided in Nicosia et al. (2009) on the marginal cost of each stage of the process (arrest, adjudication, sentence, and jail/probation/parole). The U.S. estimate represents a weighted average cost of the probable outcome of a misdemeanour possession offense or a felony sales offense. According to the Sourcebook of Criminal Justice statistics, in 2006 only 18% of all drug offenses were for sale/trafficking (which would include a jail sentence) while 82% were for possession. Taking the weighted average generates an estimate of US $21,335.

While the above exercise demonstrates the difficulty in trying to obtain reasonably consistent unit cost estimates of the significantly trimmed set of indicators that one could use to measure harms from drug use, it also highlights that there may be potential in the future depending on continuing efforts that have been initiated in some regions (i.e. Europe). The fact that the EMCDDA has been able to get some harmonization of measures for 27 different countries with very different approaches to the problem is a very promising sign. The fact that scientists are considering the cost of treating a disease by particular regions (e.g. Postma et al, 2004) is further indicative that efforts in the future may be possible. But the previous two sections also show that such efforts need to be initiated with the intention to develop consistent and comparable measures across countries; the indicators and unit cost measures that have developed in a consistent fashion across some countries have occurred because there was a concerted effort to make them that way. If there is a world goal to get a better idea of the cost of drug abuse globally, then coordinated efforts across countries in the identification, measurement, and costing of relevant indicators need to take place.

16 Costs are inflated using the country-specific inflation rate, and then converted into Euros using the average currency conversion rate for 2005. The date of 2005 for the conversion rate was done to make estimates from this report more consistent with estimates obtained in our report of the size of the global market for illicit drugs.

17 The estimates for Italy, Netherlands and Spain are approximate readings off of a graph chart presenting their results for specific European countries.

18 The average lifetime discounted cost of the disease per new case generated from this model actually was only CAN $4,568.21, far below lifetime estimates for any one disease and even smaller then the cost in the first year for Fulminant, which seemed implausible, so we went with this alternative estimate instead.

19 QALY is a subset of a full class of quality adjusted life indices (QALI) that have been developed to try to measure loss in quality of life. What’s unique about QALYs is that they measure quality of life both in terms of the amount of the disability and the survival probability of living with the illness. So the index is measured in terms of years of quality life. Other QALI indices can measure changes in well-being in terms of functioning or disability (DALYs).

20 Much of the US and European literature presumes a value of a statistical life in the range of $50,000 - $100,000 (or €50,000 – €100,000) per QALY. One review of this literature (Tolley, Kenkel and Fabian, 1994) places the value of a life year in the $70,000-$175,000 range, while another study (Cutler & Richardson, 1997) puts the number at $100,000 but both of these study presume a value of a statistical life of $1 million. More recent studies put the value of a statistical life (which is of course a function of an individual’s age, life expectancy and income) in the range of $4 million - $9 million, well above those used to monetize these QALYs (Aldy & Viscusi, 2008; Viscusi & Aldy, 2003).

21 The ideal measure of unit cost for law enforcement is the marginal cost, not the average cost, as the infrastructure for arresting, processing and adjudicating is exactly the same regardless of the crime committed. Thus, fixed costs associated with enforcement should not be considered as part of the unit cost estimates.

22 Eurostat, accessed on 24 November 2008.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|