Report 2 Methodological issues associated with demand-side estimates

| Reports - A Report on Global Illicit Drugs Markets 1998-2007 |

Drug Abuse

2 Methodological issues associated with demand-side estimates

Demand-side estimates of illicit drug markets are usually based on self-report information about expenditures and

consumption. This information can be obtained from a variety of populations, including those in treatment, those

involved in the criminal justice system, students attending school, and respondents to general population surveys.

Since many developed countries conduct nationally representative drug use surveys of the general populations (often

based on households), we rely heavily—but not exclusively—on these figures for our consumption and expenditure

estimates.

The obvious advantage of using information from general surveys is that we can generate country-specific estimates for

a large number of countries. There are, however, three important drawbacks: 1) The survey collection/analysis methods

often differ across borders, 2) Respondents are not always honest, and 3) General population surveys often miss heavy

drug users who are in treatment, in jail/prison, in an unstable housing situation, hard to locate, or unwilling to talk about

their substance use. The latter is more likely to be a concern for highly addictive drugs (e.g., heroin) compared to those

that are commonly used in the general population (e.g., cannabis). Each section discusses how these missing populations

are addressed, but in some cases we are only able to provide estimates from those covered by the general population

surveys.

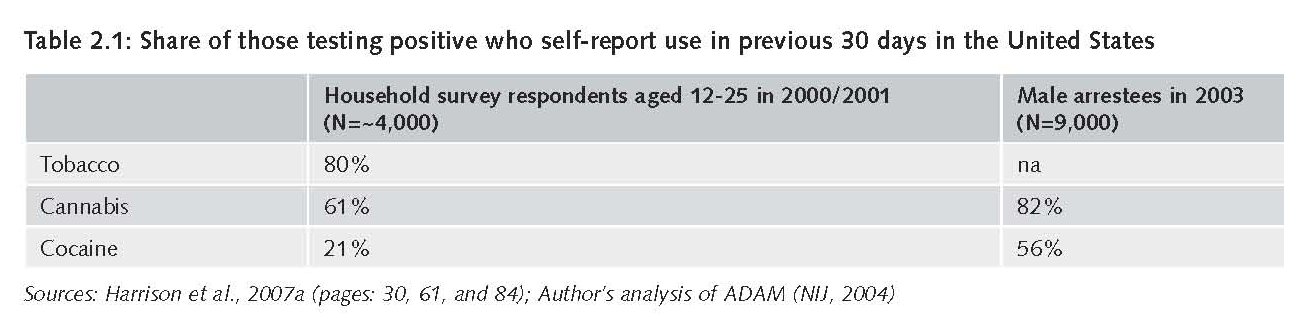

As for underreporting, a number of studies have examined this by comparing self-report information with information

from a drug test, usually urinalysis. Much of this research has occurred in North America, and here we highlight a large

U.S. study examining concordance for almost 4,000 individuals aged 12-25 who participated in the 2000/2001 National

Household Survey on Drug Abuse (Harrison et al., 2007a). Based on the results of this study, Table 2.1 presents the share

of those testing positive who actually reported using the substance in the previous thirty days (this is known as sensitivity

of the test).2 While these tests are not 100% accurate (e.g., there are false positives), they provide useful insight into the

honesty of those reporting information about drug consumption in surveys. As we would expect, the sensitivity of the

test is inversely related to the stigma (and legal penalties) associated with the substance. These results suggest that nearly

80% of tobacco users in the household population were honest about their use; the comparable figures for cannabis and

cocaine are close to 60% and 20%, respectively.

For comparison, Table 2.1 also presents the sensitivity rates for a large sample of arrestees. While there are several differences

between these two populations (e.g., arrestee rates are only based on men, arrestees are older, do not cover the

same time period), the magnitude of the difference is still striking. It appears as if these arrestees were more honest about

their drug use than the household population, which is consistent with other studies (e.g., Hser et al., 1999). Whether or

not this pattern holds outside of the United States is an empirical question.

As noted in the previous section, another drawback to the demand-side approach is that little is known about the typical

quantities consumed per use day. Thus, even if we did not have to worry about underreporting and missing populations,

there would still be uncertainty. While this report makes a useful contribution by reviewing the available international

evidence on quantity consumed for each substance, large uncertainty remains. We address this uncertainty (for this

measure and others) by presenting low and high estimates for all of our calculations In most cases we provide a best

estimate, but we are not comfortable doing this for ATS in Europe given the extremely large ranges for quantity consumed.

Readers should consider these ranges as extreme values that allow us to understand the order of magnitude.3

2 There were not enough heroin users in the sample to make comparisons and the study was unable to distinguish between legal, illegal, and OTC

amphetamines.

3 We seriously considered using a simulation approach, which would involve making assumptions about the distributions for the values and then

picking a range for the estimates; however, we ultimately decided against this approach since we wanted the readers to understand that the

large uncertainty comes from different, but reasonable assumptions about the values. We did not want readers to associate this range with

uncertainty coming from a simulation.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|