Appendix to report 4: country reports AUSTRALIA

| Reports - A Report on Global Illicit Drugs Markets 1998-2007 |

Drug Abuse

Appendix to report 4: country reports

AUSTRALIA

1 General information

Location:

Oceania, continent between the Indian Ocean and the South Pacific Ocean

Area:

7,686,850 sq km

Land boundaries/coastline:

0 km/25,760 km

Border countries:

none

Population:

21,007,310 (July 2008 est.)

Age structure:

0-14 years: 18.8% (male 2,022,151/female 1,919,002)

15-64 years: 67.9% (male 7,233,555/female 7,038,722)

65 years and over: 13.3% (male 1,266,166/female 1,527,714) (2008 est.)

Administrative divisions:

6 states and 2 territories

GDP (purchasing power parity):

$773 billion (2007 est.)

GDP (official exchange rate):

$908.8 billion (2007 est.)

GDP- per capita:

$37,300 (2007 est.) (CIA World Factbook)

Drug research

Australia has a long tradition in drug research, there are for instance several research institutes and there is a high-quality monitoring research tradition.

Key institutes: National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre (NDARC); Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Australian Bureau of Criminal Intelligence.

Main drug-related problems

Australia is a major consumer of cannabis, amphetamines and heroin. Cannabis and amphetamines are largely produced domestically. Main trafficking focus in Australia is (import) of heroin, cocaine and ATS.

2 Drug problems

2.1 Drug supply

2.1.1 Production

Australia has some illicit drug production but not for export reasons. “Australian ATS supply is dominated by domestic clandestine production, primarily of methylamphetamine.” (Australian Crime Commission, 2007). Domestic cultivation of cannabis is predominant (Australian Crime Commission, 2007).

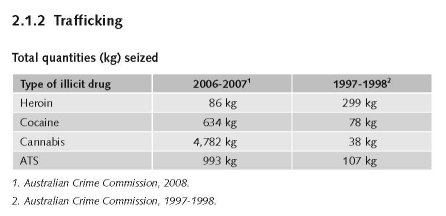

The overall trend in seizures of illicit drugs is towards a larger number of smaller shipments, i.e. over 95% in postal articles and parcels (Australian Crime Commission, 2008). This picture also goes for heroin (large number of small quantities of heroin shipped), imported mostly from or via South East Asia. Cocaine comes from Colombia, Bolivia and Peru via staging points in Africa and Asia. Seizures of large quantities remain rare. The number of ATS seizures in 2005-06 is 9,987 and the weight (in kg) was 1,297 (Australian Crime Commission, 2008).

In August 2008 the world’s largest ecstasy seizure was done, i.e. 4.4 tonnes of ecstasy (Australian Crime Commission, 2007).

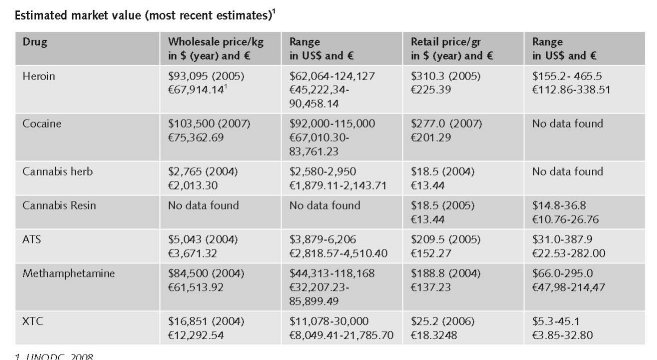

1. UNODC, 2008.

Prices are reported per territory or province, not on average for Australia (Australian Crime Commission, 2007).

1 $1= €0.728509. Exchange rate 16 December 2008.

2.1.3 Retail/Consumption

The price of heroin decreased in 2004, returning to the prices reported before the heroin shortage in 2000-2001 (Stafford et al., 2005). The annual survey of users and key informants is the national source for prices, availability, and purity. For 2006, no nationally averaged prices were mentioned for ecstasy, methamphetamine (Black et al., 2008).

No national prices were mentioned for methamphetamine or for cocaine (Stafford et al., 2005). Gram prices of cannabis varied from $20 to $25 (€14.55 to €18.20) consistent with previous year (Black et al., 2008).

2.2 Drug Demand

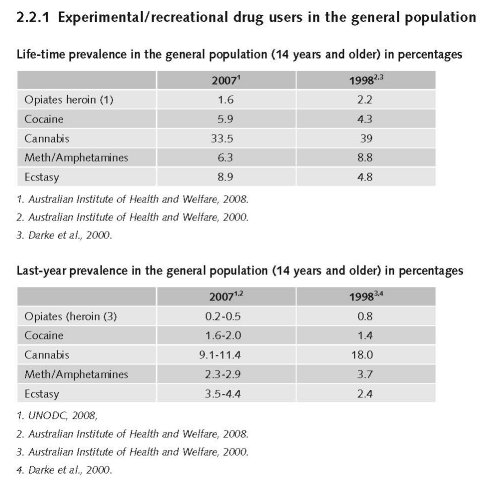

“The proportion of males who had used meth/amphetamines in the previous 12 months declined between 1998 and 2007, but a clear trend is not evident for females (…).” (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2008).

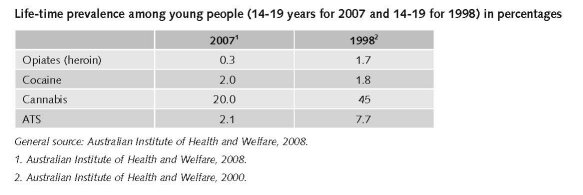

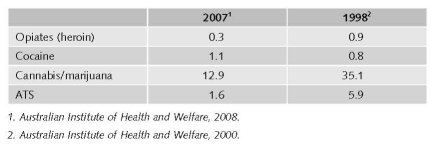

Last-year prevalence among young people (14-19 years for 2007 and 14-19 for 1998) in percentages

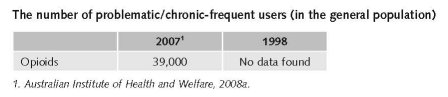

2.2.2 Problematic drug users/chronic and frequent drug users

Problematic use is not used as a measurement category. The concepts dependents versus non-dependents are used sometimes (expert’s comments).

2.3 Drug related Harm

2.3.1 HIV infections and mortality (drug related deaths)

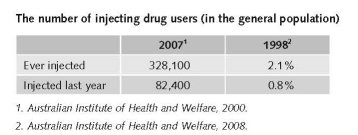

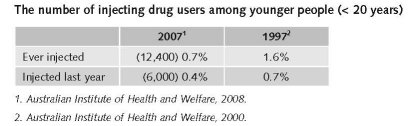

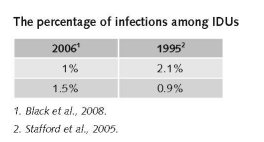

No published national data found on the number of HIV infected injecting drug users.

For 2006 this was estimated 1.5% of approximately 150,000 people who inject drugs (range 90,000 – 205,000, rounded), thus 2,250 HIV infected IDUs (Mathers et al., 2008).

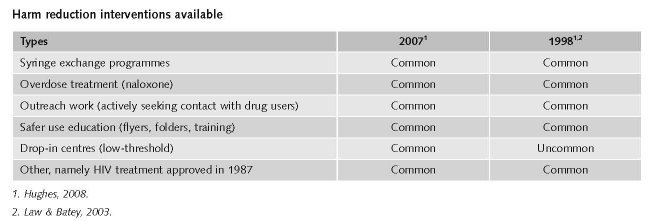

“HIV prevalence among people attending needle and syringe exchange programs has remained low (around 1% in 1998-2007). But in the subgroup of men who identified as homosexual, it was 26.1% (…). ” (McDonald, 2008).

The number of newly HIV infected injecting drug users

“Of 724 men and 456 women with a history of injecting drug use who were tested for HIV antibody at metropolitan sexual health centres in 2006-2007 three men (0.4%) and two women (0.4%) were diagnosed with HIV infection.” (McDonald, 2008).

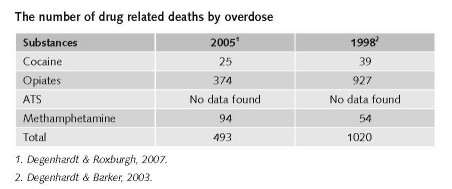

Numbers of overdose deaths over the decade are incomparable due to the heroin drought in Australia in late 2000/early 2001 (expert’s comments; Black et al., 2008).

2.3.2 Drug related crime or (societal) harm

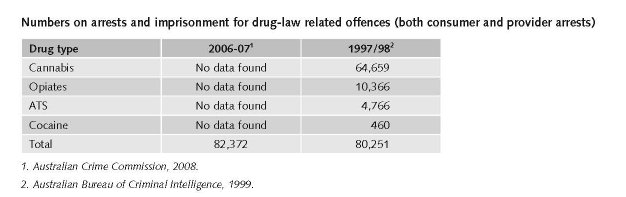

2004-05 statistics are the most recently published. The majority of illicit drug arrests are related to drug consumption rather than the provision or sale of substances. For example, in 2004-05 over three-quarters of arrests for marijuana/cannabis (84%) and steroids (83%) were related to the consumption of those substances (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2007).

The most common drug-related offence for which people were imprisoned was dealing/trafficking drugs. From 1998 to 2005 the percentages imprisoned for this offence were 7.0 and 7.9. Between 1998 and 2005, there were no significant changes in drug-related imprisonment (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2007).

3 Drug policy

3.1 General information

3.1.1 Policy expenditures

No estimates exist on specified expenditures on supply reduction, demand reduction and harm reduction (expert’s comments).

Australian governments spent in total for 2002-03 approximately $1.3 billion (€945,394,537.37)2 on proactive illicit drug policy (treatment, law enforcement, prevention, harm reduction) and at least $1.9 billion (€1,380,952,419.11)3 reactive, i.e. on the consequences of illicit drug use (i.e. ill health, acquisitive crime, amenity etc.). The majority of expenditure was enforcement-related while harm reduction accounted for only 2% of policy spending (Moore, 2005).

3.1.2 Other general indicators

Overall the numbers of drug-related arrests decreased over the past decade. Only for (meth)amphetamine this number has increased from 5% to 13% over the period 1996-97 to 2004-05 (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2007).

Numbers on arrests and imprisonment for use/possession for personal use

Number of consumer arrests in 1997-1998: 60,774 (Australian Bureau of Criminal Intelligence, 1999). Number of consumer arrests in 2006-07: 63,520 (Australian Crime Commission, 2007).

3.2 Supply reduction: Production, trafficking and retail

More specific targets are: disrupting the manufacture and supply of illicit drugs; to enhance efforts to control the inappropriate supply and diversion of pharmaceutical drugs and precursor chemicals; dismantle organised crime (Commonwealth of Australia, 2004).

The phrasing in the nationally agreed directions for drug policy has changed slightly but the content remained largely unchanged (Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care, 2001a; 2001b; 2004).

Priorities of supply reduction covered by policy papers and/or law

Since its inception in 1985, the basis of drug policy is harm minimisation, i.e. a balanced approach including demand reduction, supply reduction and harm reduction (Commonwealth of Australia, 2004).

Before 1998 a cannabis expiation notice (CEN) (a law) was initiated to keep cannabis users out of prison and instead let them pay money for offending the law (Sutton & McMillan, 1998).

2 $1=€0.727227. Exchange rate 16 December 2008.

3 $1=€0.726817. Exchange rate 16 December 2008.

More effort has been focussed on supply reduction, with less emphasis on demand reduction and even less on harm reduction. Conservative lobby groups are concerned about too much emphasis on harm reduction and not enough on demand reduction. Despite these groups, nowadays harm reduction has had more focus than prevention, but the treatment part of demand reduction remains extremely well supported, with massive expansions of Commonwealth funding to it in recent years. The National Drug Strategy is a policy established and implemented by consensus between Australia’s 9 governments and the NGO sector, not by law. There have been no significant legal changes (expert’s comments).

Limitations in the scope of changes should be recognised due to the complex nature of the Federal system of government in Australia (e.g. the widely recognised tensions between the Australian National Council on Drugs and the Intergovernmental Committee on Drugs and the number of participants in the National Drug Strategy: 9 governments, 18 Australian and 2 New Zealand Ministers, 24 government officials, and approximately 140 individuals of various ministerial committees). Furthermore, there are clear linkages between the drug strategy and a number of other related national strategies, that need to be more effectively coordinated to enhance the scope and impact of these strategies (flexible and time-limited working groups are proposed instead of expert advisory committees to render the consultative mechanisms more efficiency).

Education must be included alongside health and law enforcement with a major role for prevention (community capacity building) and early intervention. Emphasis on development and funding of the workforce (training, professional identity, and development) (Australian Government, 2003).

An evaluation of the period 2004-2009 will be reported in 2009 (expert’s comments).

Significant expansion of drug diversion programmes (diverting users away from the criminal justice system to treatment options (Hughes & Ritter, 2008).

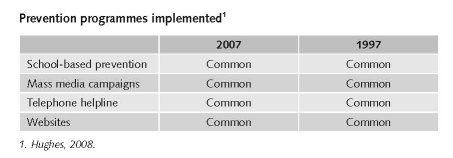

3.3 Demand reduction: Experimental/recreational drug use + problematic use/chronic-frequent use

Education must be included alongside health and law enforcement with a major role for prevention (community capacity building) and early intervention. Whether this increased focus on drug prevention has been realised is unclear. Next evaluation of the drug strategy is mid 2009 (expert’s comments).

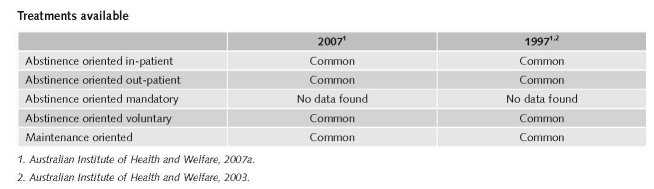

Methadone treatment is an established form of opioid substitution treatment in Australia (main focus, i.e. highest number of participants). From March 2001 buprenorphine is also available. In April 2006 Suboxone was introduced (Black et al., 2008).

Australia has Drug Treatment Court regulations (cf. Canada) giving opportunities for judges in case of drug offences to refer the convicts to treatment facilities in lieu of prison for instance (expert’s comments). Most jurisdictions have formal, sometimes legislated, provisions for this. These so-called ‘drug courts’ have been trialled, with success (Hughes & Ritter, 2008).

Priorities of demand reduction covered by policy papers and/or law

Since its inception, the basis of drug policy is harm minimisation, i.e. a balanced approach including demand reduction, supply reduction and harm reduction (Commonwealth of Australia, 2004).

The target of national drug policy is to reduce the supply and use of illicit drugs in the community. The relevant objectives are to prevent the uptake of harmful drug use and to increase access of high-quality prevention and treatment services (Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care, 2001a; 2001b).

Cooperation between law enforcement, health and other key stakeholders has increased significantly during the past years and will remain a focus in the new phase of the national Drug Strategy.

One of the more specific targets is to implement effective legislation and regulatory regimes, and education programmes for key justice and health professionals, and to implement effective legislation and regulatory regimes of alcohol, tobacco and other substances to reduce associated harms to the community.

Action will be taken to minimise barriers to treatment, support effective treatment interventions and promising new treatment options; build strong partnerships between treatment services and mental health services; increase the involvement of primary health care; improve access to treatment programmes and services in the criminal justice system; improve knowledge of the effectiveness of culturally secure treatment for specific groups (Commonwealth of Australia, 2004).

All Australian states and territories have legislation against the possession, manufacture and distribution of illicit drugs. Although the content of these legislations may be different in each jurisdiction area, the central themes are the same. Penalties are higher for those who found to be dealing in drugs than those possessing them for their own use, and people convicted of trafficking large amounts of drugs are liable for a greater penalty than lower level dealers (Australian Institute of Criminology, 2008).

3.4 Harm reduction

3.4.1 HIV and mortality

Priorities of harm reduction covered by policy papers and/or law

“Australia has largely avoided a punitive and moralistic drug policy, developing instead harm minimisation strategies and a robust treatment framework embedded in a strong law enforcement regime.” (Hall et al., 2002). Since the nineties illicit drug policy is a strategic balance between supply reduction, demand reduction and harm reduction. The balance is the cornerstone, in policy and in practice. The relevant objectives here are to reduce personal and social disruption, loss of life and poor quality of life, loss of productivity and other economic costs associated with harmful drug use (Commonwealth of Australia, 2004). For instance a National Heroin Overdose Strategy was launched that aims at:

• Increasing the number of drug users entering and remaining in treatment;

• Assisting drug users to reduce their risk of overdose and increasing awareness of the consequences of overdose;

• Improving the evidence base to inform strategies and programs to reduce overdose;

• Increasing the timelines and reliability of data in respect to overdose (Commonwealth of Australia, 2001).

Cooperation between law enforcement, health and other key stakeholders has increased significantly during the past years and will remain a focus in the new phase of the national Drug Strategy (Commonwealth of Australia, 2004).

From 2003 possession of small amounts of cannabis was not punished anymore by prosecution or imprisonment. Minor cannabis offences, including cultivation of not more than two plants, were permitted (CIN).

A few years ago, a national cannabis strategy was endorsed and published with the following priorities:

• Community understanding of cannabis;

• Preventing the use of cannabis;

• Preventing problems associated with cannabis use;

• Responding to problems associated with cannabis use.

The objective is to reduce the availability and demand for cannabis, and minimise related harms within the Australian community.

The four aims are:

• Increase community knowledge about cannabis and associated harms and influence (>) the level of acceptance of cannabis within the Australian community;

• Prevent the uptake of cannabis use and minimise use in individuals and the community;

• Prevent and minimise the social, physical, mental and financial harms of cannabis to individuals and the community;

• Provide effective and accessible interventions, tools, treatments and support for those who develop problems associated with their cannabis use (Commonwealth of Australia, 2006).

Expert comments

There were no significant changes over the past ten years in harm reduction interventions, mainly because it was set up so well in 1985 that we have 100% NSP coverage since that year. The implementation has changed, e.g. there is now more diversion of the criminal justice system toward more treatment opportunities instead of prison, more treatment resources, greater acceptance of people who use illegal drugs in policy-making forums, and an expansion of the use of infringement notices for minor cannabis offenders.

There is:

• More diversion from the criminal justice system to treatment and education;

• More treatment resources;

• Greater acceptance of people who use illegal drugs in policy-making forums;

• Greater acceptance of the role of families and friends of people experiencing drug-related harm, including overdose fatalities, in policy forums and service delivery;

• Expansion of the use of infringement notices for minor cannabis offenders;

• More mass media drug education;

• Trial of a supervised injecting facility;

• Better cooperation between law enforcement and health agencies – implementing a common policy;

• Increasing acceptance of the importance of the social determinants of health, though still struggling to incorporate this understanding into policy and action within the drug sector;

• A strengthened evidence base for law enforcement, treatment and harm reduction;

• One supervised injection centre in Sydney.

3.4.2 Crime, societal harm, environmental damage

Trends in different statistics over the years show that crime may have increased.

Obvious increase rates are present for:

• Drug abuse violation arrests (1980-2004);

• Numbers of arrests for:

- drug possession and for sales and manufacturing (1998-2006);

- different types of drugs: ceiling effect for heroin and cocaine, but increase for cannabis and other drugs and a slight increase for synthetic drugs (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2008).

References

Consulted experts

S. Lenton, Associate Professor and Deputy Director, National Drug Research Institute, Curtin University of Technology, Perth.

D. McDonald, Visiting Fellow at the Australian National University (ANU) in Canberra, Director Social Research & Evaluation Pty Ltd, Wamboin NSW 2620.

A. Ritter, Director, National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre (NDARC), Sydney.

Documents

Australian Bureau of Criminal Intelligence. Australian illicit drug report 1997-1998. Canberra, Australian Bureau of Criminal Intelligence (ABCI) (endorsed by the eight Police Commissioners in Australia and the Australasian Police Ministers’ Council), 1999.

Australian Crime Commission. Illicit drug data report 2004-05. Canberra, Australian Crime Commission (endorsed by the eight Police Commissioners in Australia and the ACC), Canberra, 2006.

Australian Crime Commission. Illicit drug data report 2005-06. Canberra, Australian Crime Commission (endorsed by the eight Police Commissioners in Australia and the ACC), 2007.

Australian Crime Commission 2008, Illicit drug data report 2006-07, Australian Crime Commission, Canberra. Available:

www.crimecommission.gov.au/html/pg_iddr2006-07.html, last accessed 20 December 2008.

Australian Government. Evaluation of the National Drug Strategic Framework (NDSF) 1998-99 – 2003-04. Canberra, Australian Government, 2003.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 1998 National drug strategy household survey. Detailed findings. Canberra, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2000.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Alcohol and other drug treatment services in Australia 2001-02. Report on the National Minimum Data Set. Canberra, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2003.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Alcohol and other drug treatment services in Australia 2003-04. Report on the national minimum data set. Canberra, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, August 2005.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Statistics on drug use in Australia 2006. Canberra, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2007.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Alcohol and other drug treatment services in Australia 2005-06. Report on the National Minimum Data Set. Canberra, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2007a.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2007 National drug strategy household survey. First results. Canberra, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2008.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. National opioid pharmacotherapy statistics annual data collection: 2007 report. Canberra, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Bulletin 62, July 2008a.

Black E, Roxburgh A, Degenhardt L, Bruno R, Campbell G, de Graaf B, Fetherston J, Kinner S, Moon C, Quinn B, Richardson M, Sindicich N, White N. Australian drug trends 2007. Findings from the Illicit drug reporting system (IDRS). Sydney, University of New South Wales, National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre (NDARC), Australian Drug Trend Series, nr. 1, 2008.

Black E, Dunn M, Degenhardt L, Campbell G, Georg J, Kinner S, Matthews A, Quinn B, Roxburgh A, Urbancic-Kenny A, White N. Australian trends in ecstasy and related rdrug markets 2007. Sydney, University of New South Wales, National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre (NDARC), Australian Drug Trend Series, nr. 10, 2008.

Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2008. Available: www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/dcf/enforce.html, last accessed 20 December 2008.

CIA - The World Factbook: Australia. Available: www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/ge-os/as.html, last accessed 20 December 2008.

CIN. Overview of Cannabis Infringement Notice Scheme (CIN). Available: www.74.125.77.132/search?q=cache:T1GNRgssoR8J:

www.dao.health.wa.gov.au/Publications/tabid/99/DMXModule/427/Default.aspx%3FEntryId%3D747%26Command%3DCore.Download+Cannabis+Infringement+Notice+Scheme&hl=nl&ct=clnk&cd=3&gl=nl, last accessed 20 December 2008.

Collins DJ, Lapsley HM. The costs of tobacco, alcohol and illicit drug abuse to Australian society in 2004/05. Summary version. Australian Government, Department of Health and Aging, Monograph No. 66, 2008.

Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care. National action plan on illicit drugs. 2001 to 2002-03. Canberra, Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care (endorsed by the Ministerial Council on Drug Strategy), July 2001a.

Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care. National action plan on illicit drugs. 2001 to 2002-03. Summary Fold-out. Canberra, Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care (endorsed by the Ministerial Council on Drug Strategy), July 2001b.

Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care. National action plan on illicit drugs. 2001 to 2002-03. Background paper. Canberra, Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care (endorsed by the Ministerial Council on Drug Strategy), July 2001c.

Commonwealth of Australia. National Heroin Overdose Strategy. Canberra, Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care (endorsed by the Ministerial Council on Drug Strategy), July 2001.

Commonwealth of Australia. The National Drug Strategy. Australia’s integrated frame work 2004-2009. Canberra (endorsed by the Ministerial Council on Drug Strategy), 2004.

Commonwealth of Australia. National Cannabis Strategy 2006-2009. Canberra, Commonwealth of Australia (endorsed by the Ministerial Council on Drug Strategy), 2006.

Commonwealth of Australia. National corrections drug strategy. 2006-2009. Canberra (endorsed by the Ministerial Council on Drug Strategy), 2008.

Darke S, Ross J, Hando J, Hall W, Degenhardt L. Illicit drugs in Australia: Epidemiology, use patterns and associated harm. Sydney, University of New South Wales, National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, 2000.

Degenhardt L, Barker B. Investigating trends in cocaine and methamphetamine mentions in accidental drug-induced deaths in Australia 1997-2002. Sydney, National Drug and alcohol Research Centre, 2003.

Degenhardt L, Barker B. Australian Bureau of Statistics data on accidental opioid-induced deaths. Sydney, National Drug and alcohol Research Centre, 2003.

Degenhardt L, Roxburgh A. Accidental drug-induced deaths due to opioids in Australia. Sydney, National Drug and alcohol Research Centre, 2005.

Degenhardt L, Roxburgh A. Cocaine and methamphetamine related drug-induced deaths in Australia. Sydney, National Drug and alcohol Research Centre, 2007.

Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations. National School Drug Education Strategy.

A Commonwealth Government Initiative. Canberra, Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations,

May 1999. Available: www.dest.gov.au/sectors/school_education_funding, last accessed 20 December 2008.

Hall W, Hamilton M, Ali R. Harm minimisation in a prohibition context – Australia. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences, 2002, 582(1): 80-93.

Hughes, C. The Australian (illicit) drug policy timeline: 1985-2007. Drug Policy Modelling Program. Last updated 31 January 2008. Available: www.dpmp.unsw.edu.au/dpmpweb.nsf/page/Drug+Policy+Timeline, last accessed 20 December 2008.

Hughes C, Ritter A. A summary of diversion programs for drug and drug-related offenders in Australia. Sydney, NDARC, 2008.

Law MG, Batey RG. Injecting drug use in Australia: needle/syringe exchange programs prove their worth, but hepatitis C still on the increase. Health Journal of Australia, 2003, 178(5): 197-198.

Macintosh A. Drug law reform. Beyond prohibition. Canberra, The Australian Institute, discussion paper Nr. 83, 2006.

McDonald A. (ed.). HIV/AIDS, viral hepatitis and sexually transmissible infections in Australia. Annual surveillance report 2008. Darlinghurst, National Centre in HIV Epidemiology and Clinical Research, 2008.

Moore TJ. What is Australia’s “drug budget”? The policy mix of illicit drug-related government spending in Australia. Draft version, May 2005.

Moore TJ. The size and mix of government spending on illicit drug policy in Australia. Drug and Alcohol Review, 2008, July, 27(4): 404-413.

Ross J. (ed.) Illicit drug use in Australia: Epidemiology, use patterns and associated harm (2nd Edition). Sydney, University of New South Wales, National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, 2007.

Stafford J, Degenhardt L, Black E, Bruno R, Buckingham K, Fetherston J, Jenkinson R, Kinner S, Moon C, Weekley J. Australian drug trends 2004. Findings from the Illicit drug reporting system (IDRS). Sydney, University of New South Wales, National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre (NDARC), 2005 (NDARC Monograph No. 55).

Strang J, Darke S, Hall W, Ali R. Editorial. BMJ, 8 June 1996, 312: 1435-1436.

Success Works. Evaluation of the national drug strategy framework 1998-99 – 2003-04. Success Works Pty Ltd., 2003.

Sutton A, McMillan E. A review of law enforcement and other criminal justice attitudes, policies and practices regarding cannabis and cannabis laws in South Australia. Canberra, Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care,

May 1998.

UNODC (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime). 2008 World Drug Report. Vienna, UNODC, 2008.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|