What Influences Young People's Use of Drugs? A qualitative study of decision-making

Drug Abuse

What Influences Young People's Use of Drugs? A qualitative study of decision-making

ANNABEL BOYS,* JOHN MARSDEN, JANE FOUNTAIN, PAUL GRIFFITHS, GARRY STILLWELL & JOHN STRANG

National Addiction Centre, London, UK

ABSTRACT Recent surveys in the UK indicate that approximately half of all young people aged 16-22 have used an illegal drug. Despite such observations, remarkably little research has been conducted in the UK about the motivating factors which shape the decisions that young people make to use drugs or alcohol. This paper reports on a qualitative study exploring the range of factors which young people reported to be influential over such decisions. Results are presented from in-depth interviews conducted with 50 16-21-year-olds. Analysis of the data revealed individual-level influences (the perceived functions of drug use (or specific purpose for using a particular substance), drug-related expectancies, physical/psychological state, commitments and boundaries) and social/contextual-level influences (environment, availability, finance, friends/peers and media) on decision-making. Of these, the perceived function for using a particular substance was identified as particularly influential. The findings are related to existing drug prevention approaches and opportunities for their further development are discussed.

Introduction

In the UK, surveys suggest that the number of young people who have tried illegal drugs has increased during the past decade. The 1996 British Crime Survey reported that 35% of 16-19-year-olds had ever used cannabis, as had 42% of young people aged between 20 and 24 years (Ramsay & Spiller, 1997). Use of the so-called 'dance drugs' was also prevalent, with amphetamine use reported by 16% of 16-19-year-olds and 21% of 20-24-year-olds; followed by LSD (used by 10% and 14%, respectively) and then ecstasy (9% and 13%). In 1995, a Health Education Authority (HEA) survey in England reported similar findings and concluded that over half of all 16-22-year-olds have tried an illicit drug (HEA, 1997). The survey also points to an increase in the number of young people who have been offered drugs (Aldridge et al., 1995; Balding, 1996; HEA, 1997). This suggests that although the number of people experimenting with illicit drugs has risen, for various reasons a significant number of young people have also decided to resist use.

Numerous etiological theories of substance use amongst young people have been advanced (see Lettieri et al., 1980, for discussion). The influence of the environment or 'setting' where substance use takes place on behaviour has also been recognized (Zinberg, 1984). In general, early work regarded individuals as essentially passive and influenced by social and environmental circumstances (e.g. Elliott et al., 1989, 1985) while more recent perspectives have focused on active decision-making in which an individual considers the costs and benefits of taking a substance (e.g. Ajzen, 1985, 1988; Langer & Warheit, 1992).

Much of the work in this area has tended to focus on the decision to initiate into use of a given substance. However, although this decision is an important one, once initiation has occurred, an individual's decisions about substance use do not cease. Decisions are made about whether to use the substance on subsequent occasions and if so, how much to consume. Glasner & Loughlin (1987) observed that there were certain occasions when almost all of the young people in their study (including the heaviest users) decided against using drugs. They suggested that users had fairly rigid rules governing their drug-taking behaviour and established certain boundaries that they would not cross. The majority of their sample regarded their substance use as reflecting self-controlled choices.

There is evidence that young people's beliefs or expectancies about the effects of alcohol predict future drinking patterns (Christiansen et al., 1989). However, little is known about the effects of other substance-use expectancies. It seems that expectancies concerning the effects of specific drugs are not necessarily solely based on their pharmacological effects, but are heavily influenced by reports from peers and socio-cultural factors (Stacy et al., 1994). Studies have also explored the reasons and motivations cited by substance users for their behaviour. In some reports, these reasons vary from quite broad statements (e.g. to feel better) to more specific roles or functions for use (e.g. to increase self-confidence). However, much of this literature focuses on 'drugs' as a generic concept and makes few distinctions between different types of illicit substances (e.g. Butler et al., 1981; Carman, 1979; Cato, 1992; McKay et al., 1992; Newcomb et al., 1988).

A considerable range of approaches and methods have been employed by drug education and prevention programmes. Some recent efforts have focused on the role of peers, the family, and attitudes and values held by an individual. These programmes have attempted to train young people to resist tempting forces such as 'peer pressure'. Others have used peer-educators to deliver drug prevention messages on the assumption that such messengers are more credible to a young population and are more likely to succeed. An alternative approach has been to encourage diversionary activities as alternatives to drug use. A central premise of this work is that young people use drugs because they lack access to other satisfying activities or because they are bored (Coggans & Watson, 1995). Thus it is hoped that providing young people with attractive alternatives to drug use with which to fill their leisure time will reduce motivations to use drugs.

There has been little qualitative study of the processes involved in substance-related decision-making. The identification of influential factors and exploration of their relative importance, could help to develop and inform new approaches to prevention and education. The primary objective of this paper is to describe the critical influences on substance-related decision-making amongst a sample of young users.

Method

Fifty young people (24 male, 26 female) were interviewed. Their average age was 18.5 years (range 16-21). All participants were recruited from the south of England using snowballing techniques with seven starting points with the aim of obtaining a range of ages, occupations (and thus incomes) and social backgrounds. The starting points included: a charity for homeless young people, a Further Education College, a youth club, a student nurse, a Higher Education College and a drug dealer. Given the aims of the study, a purposive sampling procedure was employed to recruit a diverse range of young people whose experience of substance use was in excess of national norms for this age range. Consequently, selection was not intended to provide a representative sample of young people from this age group. For more detail on the methods used, see Boys et al., 1999.

A brief, structured interviewer-administered questionnaire was used to record demographic characteristics and lifetime use and recent consumption patterns of five target substances: alcohol, cannabis, amphetamines, LSD and ecstasy use, based on procedures developed by Marsden et al. (in press). A semi-structured interview was then employed to discuss the following topics: drug use of friends, personal drug use experience, decision-making and reasons for not using drugs. Respondents were encouraged to give as much information as they wanted to in response to questions. Interviews were tape-recorded with the interviewee's consent, and subsequently transcribed. A synthesis of analytic induction and grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967) was used to guide the analysis of the qualitative data.

Results

Sample Characteristics

The majority of respondents (n=36; 72%) described their ethnic origin as 'white'; nine (18%) as African-Caribbean or Black British; three (6%) as mixed race and two (4°/0) as Asian. Half the sample reported that they were living with their parent(s). Nine were living in temporary hostels or on the street and the remainder were currently living in rented accommodation. Twenty-seven respondents were in some form of education; 13 had full-time work and the remaining 10 were unemployed.

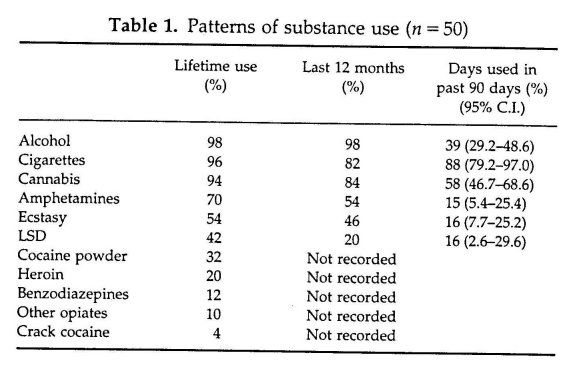

All reported having drunk alcohol with friends, and the majority of the sample had also smoked tobacco (96%) or used cannabis (94%). Seventy per cent of the sample had used amphetamines, 54% ecstasy (MDMA) and 42% LSD (see Table 1). Analyses of rates of lifetime use of these substances did not differ between male and female respondents (x2 values did not exceed 2.81 for any comparison, p = 0.09 or greater).

In the context of the qualitative interview, none of the respondents described dependent patterns of use of the five targets. No respondent reported using substances to relieve withdrawal symptoms or craving.

Respondents were asked to estimate their weekly discretionary disposable income. This was defined as money in excess of that which was needed to pay for accommodation and other living costs. Estimates of this income ranged from £14 to £420 with a mean of £75 (median = £50) per week. Spending priorities varied, though most respondents cited socializing, night-club entrance fees and also buying alcohol or drugs.

Substance-use Decision-making

A thematic analysis of the interview transcripts yielded 10 factors which were cited as influential on substance-related decision-making. These were then classified into two broad influence domains: individual-level influences and social/contextual-level influences.

Individual-level Influences

Five individual-level influences were observed: the functions of substance use, substance-related expectancies, physical/psychological state, role commitments and boundaries.

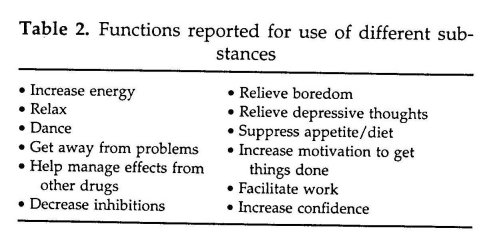

Functions Respondents highlighted a range of specific roles or functions for their substance use. Twelve general functions were identified (Table 2). Many of these were associated with facilitating social events or gatherings at night-clubs, pubs or friends' houses. Other functions related to specific aspects of some users' lifestyles. Examples included using cannabis or amphetamines in association with work or study to facilitate concentration, relieve boredom or increase motivation. As three respondents described:

When I'm on cannabis, I feel I make more conscious decisions because I can concentrate more ... I usually have it before I go to work [waitressing] and I enjoy work so much more if I am stoned [intoxicated]. (006: female aged 19)

I was working at [a large department store] as a Saturday job while I was at college ... and I spent about E15 [a day] on speed [amphetamines] to keep me going—to make it more enjoyable because it [the job] bored the hell out of me. (008: male aged 21)

When I was doing my A levels, I went through a stage of using it [amphetamines] every day and its just so good because you're on top of everything ... if someone comes up to you and says 'Right I want a 2500 word essay for tomorrow' and you're like 'yeah! Whatever!' and that's why I like it because I'm not an organised person anyway ... and certainly round exam time it is quite handy. (012: female aged 18)

Others reported that they used drugs or alcohol to help them to cope with negative moods. This was also particularly common amongst the few respondents who were experiencing social problems such as homelessness. The following view was from an 18-year-old female who had been sleeping rough for 9 months:

If someone's upset me or I'm in a bad mood, then I'll beg up £10 and I'll go and get an amp [ampoule of methadone] ... but if I'm in quite a jolly mood, then I'll get cannabis. (038: female aged 18)

This young woman had found that using methadone was a more effective means of achieving a positive state of mind than using cannabis.

An amp [ampoule of methadone] makes you gouch [opioid-induced drowsiness] and you forget about everything ... I mean cannabis can help because it makes you laugh and so you can sit there and think things are funny, but you know amps block everything out whereas on cannabis you can still think about it, still think 'ohh they really pissed me off' and then you get a bad buzz with cannabis whereas with amps you know what I mean, you just get the same buzz.

(038: female aged 18)

Amongst respondents with established drug-using repertoires, different substances were often used for different functions. Several respondents described using alcohol when socializing in public (to relax and feel more confident), ecstasy or amphetamines when going to a night-club (to help them to stay awake all night and feel energetic), and cannabis to manage the effects of the 'comedown' (after-effects) from stimulants, to relax at home with friends or to induce sleep. We also found some evidence that a belief that a particular substance was better than another at fulfilling certain functions might lead to increased use of one and decreased use of another. For example, a 19-year-old female had recently started drinking heavily with a new group of friends at weekends instead of using large quantities of ecstasy and amphetamines. This change in behaviour was prompted when she realized that the feelings of depression that she was noticing during the week could be related to her weekend use of stimulants. This led to the decision to pull away from her stimulant-using friends and spend more time with another group. However, she still reported the desire to use a substance to facilitate social interactions and had found that drinking alcohol helped to do this:

... Do you think your drinking has increased since you've stopped using ecstasy so much?

Yeah—probably because of the group of friends I'm with ... I've always been quite a heavy drinker, but now at weekends, instead of going out, taking drugs and drinking water, I go out and get drunk.

(006: female aged 19)

Expectancies Expectancies about the effects of a drug appeared to be influential in decision-making. Respondents tended to report that they used drugs with stimulant properties when they were going out to a club or wanting to stay up all night, whereas other drugs such as cannabis were generally used for relaxation and to encourage sleep. For example, if someone wanted to use a drug to help them to stay awake late to write an essay (the function for the use) they would need to choose a substance which they believed would help them to stay awake, but would not impair concentration. The following excerpt from an interview with a 21-year-old male suggests that he had clear expectations concerning the effects of ecstasy before trying it for the first time:

Well I did know what the effects were because a lot of my friends at the time were already into the rave scene ... I was into the rave scene, but I was just doing speed, just to keep me going and by the time I actually got round to using ecstasy, I'd already seen what ecstasy was doing—what it did to other people. (020: male aged 21)

How an individual rated their expectancies of a drug's effects was also important. If they had disliked an experience with a drug, then they were likely to expect a similar experience on the next occasion of use and were thus more likely to decide against subsequent use. This was illustrated in an interview with a 21-year-old male:

I'd never take acid [LSD] again or any strong hallucinogen ... coz it just [expletive] my head up ... makes me paranoid, I lose myself completely in it—it completely takes control over me. (008: male aged 21)

There was also evidence to suggest that expectancies can become more sophisticated as experience or information about a drug increases. A hypothetical example of this could be that an initial expectation about cannabis might be 'cannabis makes me giggly'; as more experience is gathered from observations of others, listening to stories or from increased personal use, this expectancy could be modified to take dosage into account: 'cannabis makes me giggly if I smoke a little and very dopey if I smoke a lot'. With the addition of another substance, such as alcohol, a further modification could be: 'cannabis makes me giggly if I smoke a little, dopey if I smoke a lot, but if I smoke cannabis after drinking alcohol, then I get sick'.

Physical/psychological state Another influence on the drug-related expectancies held by an individual is their current physical and/or psychological health state. There were reports that these influences played a crucial role in decisions to use substances on a particular occasion. Some mentioned that their physical state influenced the decisions that they made. For example, an individual might take into account how tired they were or if they were already experiencing effects from other substances when deciding whether or not to consume a drug.

Psychological state was also important. In the following extract a male respondent explained how his current mood might affect whether or not he decided to try a new substance:

If I'm in a good mood, if I'm not feeling depressed, if I'm happy with the way I am for the minute and if I'm in a room full of friends that I'm close enough to to be able to say 'look I'm going to be sick is it alright if I go and puke in your bathroom?', you know I might.

(013: male aged 21)

He went on to explain how these sorts of factors influenced the drug and alcohol-related choices that he made on a regular basis. This particular respondent had set rules and boundaries concerning substance use, which were intended to insulate him from the risk of developing drug-related problems.

I never do drugs to cheer myself up—I will smoke cannabis to calm myself down, but if I'm feeling depressed then I will never do ecstasy ... I will never to speed or LSD or anything in order to cheer myself up, I'll only ever do it if I'm already happy.

Why won't you do it to cheer yourself up?

Because that's what I see as then becoming psychologically dependent on the drug because if you do it once, obviously next time it happens then you'll just go 'oh—I'll do it again', and then you'll do it again and again and again and that's how addiction would over-take me ... but if I make sure that I'm happy and relaxed and everything, before I take the drug then I know that its not the drug that's making me happy, its me that's making me happy and its just the drug that's making it better! And therefore I don't feel any dependence on the drug.

(013: male aged 21)

One experienced LSD user believed that one's current psychological state would impact on the effects experienced from this drug:

I always stop people from taking it [LSD] when I'm with them if they've got problems at that time, coz ... if you're dwelling on something that's depressing you, all the emotions that you've bottled up do come out on LSD. (009: male aged 20)

Role commitments Role commitments (e.g. work or college responsibilities) were cited by several interviewees as having a marked influence over the types and quantities of drugs or alcohol that they decided to consume on a specific occasion. This appeared to be particularly important in limiting the use of drugs perceived to be long-acting (e.g. ecstasy or LSD). Substances such as cannabis and alcohol were used routinely, but often in smaller quantities.

Well yeah Fridays and Saturdays pilling [taking ecstasy pills] but probably still smoke on Sundays as well as in the week ... I did smoke more in the week, but I've tried to cut down on that coz you don't get things done and ... you end missing lectures. (021: male aged 20)

The influence of role commitments appeared to differ between individuals and was often mediated by expectancies concerning the severity of after-effects and the relative importance of the commitment compared with substance use and socializing. If a respondent had commitments the next day, they might select a drug type that they did not expect to feel negative after-effects from. For example, one male reported that after taking amphetamines he often felt 'groggy' or depressed for the 2 or 3 days afterwards. However, he felt 'fine' after taking ecstasy, and felt 'great' on a morning following cocaine use. He explained how he would decide between different drug types during an evening out with friends:

Does how you feel afterwards affect how you decide what you are going to use?

Yeah, depending on if I have things to do the next day—if I do then I'd probably choose ecstasy, coz I can come down quite easily on that ... if I could afford coke then I'd have that. (020: male aged 21)

Boundaries The majority of interviewees described fairly rigid rules which governed their substance use and there were certain boundaries which they reported that they would not cross. Respondents with similar drug-related experiences seemed to share the same basic rules. Heroin, crack and any injecting drug use was perceived by most of the sample as different from (and more dangerous than) other forms of drug use. Some bracketed cocaine powder with these substances, whereas other, more experienced drug users perceived cocaine as similar to ecstasy and amphetamines.

Do your friends use cocaine?

No—a lot of them would like to, but you don't get much coke in [name of county]!

What about crack?

No I don't think anybody would ... well ... probably the odd person who takes heroin would do crack, but all the other people wouldn't ... because as far as me and 99.9% of my friends are concerned, you get so far and then there's a line and then across that line is heroin and crack and stuff—the things that you just don't do because they're too strong for people to handle and shouldn't be touched. (013: male aged 21) ... it seems OK to take Es and speed and things but wrong to take heroin—I think that's [the opinion of] my social circle.

(014: female aged 20)

Social/Contextual-level Influences

Five social/contextual-level influences were identified: environment, availability, finance, friends/peers and media.

Environment It was common to talk about needing to be in the 'right sort of place' when using certain drugs, particularly those with hallucinogenic effects. Some individuals reported that they had decided against trying a substance for the first time because their immediate environment had seemed unsuitable. There were clear trends in the types of environment or context that respondents felt were suitable for different types of substance use. For example, although using LSD in a club environment was not unknown, most users reported preferring to use it under less crowded, more predictable circumstances. This seemed to be due to concerns that users might experience anxious or paranoid-type ideation or otherwise get themselves into trouble.

I would never want to be in a club [when under the influence of LSD] because of the paranoid side of it, I'd rather be round a friends house and all of us take it, I would not like to take it on my own, I'd want everyone to be using the same drug and experiencing the same kind of thing as I would ... I'd rather be in someone's house or sitting in a field lying down or watching the world go by. (015: male aged 18)

Some also mentioned that whilst under the influence of LSD, they would prefer to avoid contact with people who had been drinking heavily.

If we're going to get off our heads [under the influence of LSD] it's a whole lot safer doing it out of the city, then you're not likely to walk into some of the [idiots] you get round here who go out looking for trouble, so we prefer to avoid that or go to people's houses ... especially if we're gonna take something like LSD—you don't know what you're doing, especially if you come across someone who's been drinking and is really [aggressive]. (009: male aged 20)

For most, the use of ecstasy was firmly linked with going to night-clubs. However, there were strong opinions as to what type of night-club was suitable for this and similar sentiments to those described by LSD users were expressed concerning interactions with people who had been drinking heavily.

Availability A profoundly obvious influence on a decision to use a substance is whether it is available. However, the relative ease with which a substance can be obtained (i.e. how much it costs the individual in time and effort) mediates this decision. An important finding was that if a preferred drug was unavailable, participants reported they did not necessarily decide against any form of substance use on that particular occasion. Instead, a decision was often taken to use a substitute substance. Examples of this included substituting amphetamines for ecstasy (or vice versa) or caffeine pills for amphetamines.

I only use speed [amphetamines] in like dire emergencies when I like really feel like doing some drugs and there's nothing around ...

(047: female aged 18)

Have you ever used Pro-plus [an over-the-counter caffeine-based tablet]?

When we were on holiday then we used it ... with drink, because we couldn't get anything out there and—just like in place of speed [amphetamines]. (017: female aged 18)

There were also some reports that a lack of availability of a preferred drug had prompted initiation into the use of another, often 'harder' drug type.

The first time I took speed [amphetamines], I was about 16, was when I couldn't get any cannabis ... we didn't want to get pissed because you really do get bored of drinking all the time and we wanted to have a good time, couldn't get any cannabis while we were in the pub (we asked why and they said that everyone had been busted—the police had basically done all the dealers—stopped all the supply and so it had gone dry), so we were offered some speed and we took it ... same with ecstasy, first time I took ecstasy was coz there was no cannabis on the market. (009: male aged 20)

In such cases it seems that the respondents were motivated to obtain a specific drug for a specific purpose. The discovery that their drug of choice was unavailable gave them the incentive to find an alternative means of fulfilling that function. On occasions this resulted in the use of an alternative substance that they might not have considered using otherwise.

Finances Money was frequently cited as a important influence on decision-making, particularly when deciding whether to use a substance on an occasion and which type to obtain. For example, some respondents who commonly used ecstasy at night-clubs reported that if their money was limited, they might choose to use amphetamines instead. Alternatively, if money was more readily available, cocaine might be selected. However, financial constraints did not seem to influence the use of cannabis in the same way, particularly amongst the more regular users. Instead, some reported that they sold small quantities of cannabis to friends in order to earn their own supply for free. In times of limited finance, they could therefore manage without moderating their use.

Do you always have enough money for cannabis?

Well sort of—I've sold a bit here and there when I've been totally skint [lacking money], to get by ...

If you're totally skint, then you'll sell a bit, but otherwise you don't?

No ... it's not worth the risk really ... I certainly wouldn't do it here [London], but in [county] its perfectly acceptable that if you're a bit skint you can sell a bit ... and no-one really worries about it.

(012: female aged 18)

In contrast to this, consumption of other illicit drugs tended to be reduced when money was limited. There were frequent statements that finances limited use of drugs such as ecstasy and cocaine but there were no reports of dealing these drugs in order to continue using when money was limited.

Friends/peers Many respondents socialized with more than one group of friends. Although close friends were often reported to have similar substance-using patterns to their own, it was not uncommon for friends from different social circles to have very different patterns of use. Some respondents differentiated between circles of friends according to their substance use, referring to non-drug users as their 'straight friends'. A few reported that they would tailor their own substance use to fit within the group norms of those they were socializing with on a particular occasion.

The data suggest that friends were definitely associated with the opportunity to use drugs. However, although the concept of 'peer pressure' was often mentioned by interviewees, the prevailing opinion seemed to be that drug use was engaged in through choice rather than as a result of social pressures. This could be likened to other situations where if someone has enjoyed an experience they might be motivated to encourage their friends to share the experience. However, a variety of other social and contextual factors were also described by respondents as having an influence over their substance-related choices suggesting that the process is complex and multifaceted.

There was also evidence that friends provided moral support to users as the following extract shows:

I don't like to do things on my own ... I like to have at least one person on my wavelength—otherwise I might get paranoid.... If I go out with someone its normally a close friend—I want to go out with someone who I trust in case something does go wrong ... you know if I had a bad reaction to anything or ... So it always has to be someone who I trust completely and who would know what to do if something does happen ... and the person that I go out with I won't leave ... I'll stay with them all night. (011: female aged 19)

Media Some respondents cited media coverage as being influential over their decision-making. In most cases, this concerned ecstasy use. In these instances, news stories of ecstasy-related deaths had led these young people to the conclusion that the possible benefits of using were not worth the risk of negative effects. However, other respondents dismissed these accounts completely, or offered explanations which cast the vic-ums as incompetent drug users. Some had constructed rules for themselves which they believed would keep them safe when using ecstasy:

People are weird about the dangers z‘f it (ecstasy) coz of all the hype you get in the media ... but that reLly is dogma—if you use ecstasy, you find out that it really isn't as dangerous as they say in the media and the dangers can be reduced by watching your temperature, drinking—not drinking too much ... theght amount—and by taking salt and isotonic drinks and avoiding he: and cramped conditions like you get in clubs. (021: male age 20)

In contrast, the lack of high-profile media stories relating to amphetamines seemed to have prompted many to deduce that this drug was far less dangerous than ecstasy. Consequently these individuals were motivated to use this drug instead.

Discussion

This paper presents a qualitative study of substance-related decision-making amongst young people aged 16-21. A pu_7:osive sampling procedure was used to recruit individuals whose experience of substance use was in excess of national norms for this age range.

A thematic analysis of the data yielded :0 factors which were seen to influence the decisions made by the sample. These factors were classified into five individual-level influences (the functions of drug use, drug-related expectancies, physical/psychological state, corrunitmenrs and boundaries) and five social/contextual-level influences (environment, availability, finance, friends/peers and media). A focus on any one of these fac-:ors could provide an opportunity for prevention measures to influence the deLsions made by young people. Furthermore, addressing several of these factors at once, might considerably strengthen the effectiveness of such prevention prc-ammes, by tackling the issue from several stances.

To date, measures to reduce the overa: availability of illicit substances have been the cornerstone of national and interhational drug policy. This continues to be a key aim in the revised UK drug stra:egy (Tackling Drugs to Build a Better Britain, 1998). However, it is recognized -.hat supply reduction is unlikely to be successful in isolation. Indeed, there is evidence from the present study that if a preferred substance is unavailable a:, individual may choose to use an alternative substance instead. It is unclear what overall public health benefits are likely to accrue from such selective subs:itution of one substance for another.

Approaches to drug prevention from a health education perspective have generally targeted two factors: the influence of peers and substance-related expectancies. For the former, programmes have tried to equip young people with the skills to resist 'peer pressure' to use drugs; for the latter, mass-media campaigns have been employed to communicate the potential negative effects of substance use. However, the evidence that media campaigns are effective is limited, particularly if the target audience already has personal experience of substance use and has conflicting positive expectancies concerning a drug's effects. Although some of our respondents cited general mass media as a major influence over their decision-making, these views tended to focus on coverage of ecstasy-related deaths. In contrast, many respondents had either dismissed these accounts completely, or offered explanations which cast the victims as incompetent drug users.

The importance of recognizing the functions, or the specific purpose which substance use serves, was highlighted in our data. A total of 12 different functions for substance use were identified. This list is unlikely to be comprehensive and further research is required to provide a more detailed understanding of this area. It may be that substance use fulfils a variety of functions for an individual which could be described in a hierarchy. For example, amphetamine use at a night-club could primarily help the user to stay awake all night and dance energetically. Secondary functions might include increased confidence or decreased inhibitions. Further exploration of these motivations could make a useful addition to models which aim to explain substance-use behaviour.

To date, much of the discussion around why some young people choose to use drugs while others do not has focused on the role of peers. There was evidence in the present study that friends and peers are important in providing opportunities for drug use and supporting this behaviour. However, their influence was perceived to be only one of a range of influences and reports of using drugs when alone were not uncommon. Emphasizing the functions of substance use may enable concepts such as 'peer pressure' or 'peer influence' to be acknowledged without regarding them as the sole explanation for all forms of substance use. On the one hand, people who seem influenced by peer drug use could be described as using drugs with the function of helping them to feel part of a social group. On the other hand, reports of the solitary use of amphetamines by a young sales assistant who worked long hours could be explained primarily in terms of the functions this drug served to help him/her feel more energetic and less tired.

Besides helping to explain substance use, a functional perspective could also inform drug education programmes. Our results pointed to different functions served by using particular drugs and a different profile of functions across different substance types. For example, reported functions for amphetamine use ranged from relieving fatigue at work, dieting or staying awake, to motivating users to be organized. Most literature targeting young amphetamine users assumes that use is linked to socializing. Developing our understanding of the range of functions that drug use fulfils could inform prevention programmes targeting different contexts of use. There is also scope for developing prevention strategies which encourage recognition of the functions that substance use plays for some young people and which promote alternative means for fulfilling these roles. For example, people who use cannabis to induce sleep or alcohol to relax them in social situations could be shown alternative methods for achieving these goals. This approach could be perceived as similar to diversionary programmes in that alternatives to substance use might be offered. However, to date, the evidence for the success of such programmes is weak (Cook et al., 1984; Kim, 1981; Moskowitz et al., 1983, 1984; Stein et al., 1984). One reason for this could be that the functions that substance use serves for participants have not been targeted. Instead programmes have hinged on the assumption that use stems from boredom and if young people are encouraged to fill their time with alternative activities, this will alleviate the need to spend time engaged in drug or alcohol use. Whilst offering young people exciting leisure pursuits may be valuable, it is perhaps unreasonable to expect this to prevent substance use unless the gains from participation are similar to those perceived from using substances. The challenge is to find alternatives which fulfil the same functions as drug or alcohol use and are equally attractive to young people.

In addition, it may be unhelpful for education programmes to make a division between alcohol and illicit drugs when their use is clearly linked for many individuals Prevention programmes that aim to deter all illicit substance use overlook the possibility that someone who has been using drugs heavily could substitute a licit alternative in comparable quantities thus exposing themselves to similar (or even greater) health risks.

Overall, this study has identified a complex set of factors which influenced the substance-related decisions made by this small sample group of young people. Our results suggest that prevention strategies that do not take into account these complex processes or merely target one influence on decision-making are likely to be at best ineffectual and at worst counterproductive. Further research using quantitative methods is likely to be valuable in determining the relative importance of these factors for different groups of people using different types of substances. Additionally, further work could examine variation according to frequency and quantity of use, in the decision-making processes used.

Acknowledgement

The research described in this paper was supported by funding from the Health Education Authority (HEA). The views expressed are those of the researchers and are not necessarily those of the HEA.

References

ALDRIDGE, J., PARKER, H. SE MEAsHAm, F. (1995). Drugs Pathways in the 1990s: adolescents' decision-making about illicit drug use. Manchester: SPARC, Department of Social Policy and Social Work, University of Manchester.

AZJEN, I. (1985). From decisions to actions: a theory of planned behaviour. In J. KUHL & J. BECKMANN (Eds), Action-control: from cognition to behaviour (pp. 11-39). New York: Springer.

AZJEN, I. (1988). Attitudes, Personality and Behaviour. Homewook, IL: Dorsey Press.

BALDING, J. (1996). Young People and Illegal Drugs in 1996 Exeter: Schools Health Education Unit, University of Exeter.

BOYS, A., FOUNTAIN, J., MARSDEN, J., GRIFFTIHS, P., STILLWELL, G. & STRANG, J. (1999). Drugs decisions: a

qualitative study of young people, drugs and alcohol. Health Education Authority, London.

BUTLER, M.C., GUNDERSON, E.K.E. & BRUNT, J.R. (1981). Motivational determinants of illicit drug use: an assessment of underlying dimensions and their relationship to behaviour. International Journal of the Addictions, 16, pp. 243-52.

CARMAN, R.S. (1979). Motivations for drug use and problematic outcomes among rural junior high school students. Addictive Behaviours, 4, pp. 91-93.

CATo, B.M. (1992). Youth's recreation and drug sensations: is there a relationship? Journal of Drug Education, 22, pp. 293-301.

CHRISTIANSEN, B.A., SMITH, G.T., ROEHLING, P.V. & GOLDMAN, M.S. (1989). Using alcohol expectancies to predict adolescent drinking behaviour after one year. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 57, pp. 93-99.

COGGANS, N. & WATSON, J. (1995). Drugs education: approaches, effectiveness and delivery. Drugs: education, prevention and policy, 2, pp. 211-224.

COOK, R., LAWRENCE, H., MORSE, C. & ROEHL, J. (1984). An evaluation of the alternatives approach to drug abuse prevention. International Journal of the Addictions, 19, pp. 767-87.

auorr, D.S., HUIZINGA, D. & AGEroN, S.S. (1985). Explaining Delinquency and Drug Use. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

ELLIOTT, D.S., HUIZINGA, D. & MENARD, S. (1989). Multiple Problem Youth: delinquency, substance use and mental health problems. New York: Springer-Verlag.

GLASER, B.G. & STRAuss, A.L. (1967). The Discovery of Grounded Theory: strategies for qualitative research. New York: Aldine.

GLASNER, B. & LOUGHLIN, J. (1987). Drugs in Adolescent Worlds: burnouts to straights. London: Macmillan.

HEALTH EDUCATION AuThoRrrY/BMRB INTERNATIONAL (1997). Drug Use in England: results of the 1995 National Drugs Campaign survey. London: HEA.

KIM, S. (1981). An evaluation of ombudsman primary prevention program on student drug abuse. Journal of Drug Education, 11, pp. 27-35.

LANGER, L.M. & WARHErr, G.J. (1992). The pre-adult health decision-making model: linking decision-making directednessorientation to adolescent health related attitudes and behaviours. Adolescence, 27, pp. 919-48.

LETrIERI, D.J., SAYER, M. & PEARSON, J.W. (1980) Theories on drug abuse: selected contemporary

perspectives. NIDA Research Monograph 30. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office.

MARSDEN, J., GOSSOP, M., STEWART, D., BEST, D., FARRELL, M., EDWARDS, C., LEHMANN, P. & STRANG, J. The

Maudsley Addiction Profile (MAP): a brief instrument for assessing treatment outcome (in press). McKAY, J.R., MURPHY, R.T., McGuIRE, J., RIVINUS, T.R. & MAISTO, S.A. (1992). Incarcerated adolescents' attributions for drug and alcohol use. Addictive Behaviours, 17, pp. 227-35.

MOSKOWITZ, J., MALVIN, J., SCHAEFFER, G. & SCHAPPS, E. (1983). Evaluation of a junior high school prevention program. Addictive Behaviours, 8, pp. 393-401.

MosKowrrz, J., MALVIN, J., SCHAEFFER, G. & SCHAPPS, E. (1984). An experimental evaluation of a drug education course. Journal of Drug Education, 14, pp. 9-22.

NEWCOMB, M.D., CHOU, C.-P., BENTLER, P.M. & HUBA, G.J. (1988). Cognitive motivations for drug use among adolescents. longitudinal tests of gender differences and predictors of change in drug use. Journal of Counselling Psychology, 35, pp. 426-38.

RAMSAY, M. & SPILLER, J. (1997). Drug Use Declared in 1996: latest results from the British Crime Survey. London: Home Office.

STACY, A.W., LEIGH, B.C. & WEINGARDT, K. (1994). Memory accessibility and association of alcohol use

and its positive outcomes. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 2, pp. 269-282.

STEIN, J.S., SWISHER, J.D., Hu, T. & MCDONALD, N.S. (1984). Cost effectiveness evaluation of a channel

one program. Journal of Drug Education, 14, pp. 251-69.

TACKLING DRUGS TO BUILD A BE! 1ER BRITAIN (1998). The Government's 10-year Strategy for Tackling Drug

Misuse. (1998) London: The Stationary Office.

ZINBERG, N.E. (1984). Drug, Set and Setting: the basis for controlled intoxicant use. Yale University Press.

Last Updated (Saturday, 29 January 2011 10:45)