Substance use among young people: the relationship between perceived functions and intentions

Drug Abuse

RESEARCH REPORT

Substance use among young people: the relationship between perceived functions and intentions

ANNABEL BOYS, JOHN MARSDEN, PAUL GRIFFITHS, JANE FOUNTAIN, GARRY STILLWELL & JOHN STRANG

National Addiction Centre, London, UK

Abstract

Aims. To explore the relationship between young people's use of psychoactive substances, perceived functions for using, the experience of negative effects, and the influences of these variables on their intention to use substances again. Design. Cross-sectional survey in which respondents were purposively recruited using snowballing techniques. Setting. Interviews were conducted in informal community settings. Participants. One hundred young drug and alcohol users (45 females) aged between 16 and 21 years. Measurements. Life-time prevalence, current frequency and intensity of substance use and intentions to use again were assessed for four target substances (alcohol, cannabis, amphetamines and ecstasy) together with measures of the perceived functions for their use and peer substance involvement. Findings. The life-time experience of negative effects from using the assessed substances was not found to correlate with current consumption patterns. Statistically significant associations were observed between the reported frequency of taking substances and the perceived social/contextual and/or mood altering functions cited for their consumption. The substance use function measures together with the reported extent of peer use were significant predictors of intentions to use again. Conclusions. If these findings are confirmed in larger studies, educational and preventative efforts may need to acknowledge the positive personal and social functions which different substances serve for young people. The results also call into question the extent to which the experience of negative effects influences future patterns of use.

Introduction

This paper reports findings from a study of the personal and social influences on substance use among young people. There is widespread con-cern about this issue in many countries, including the United Kingdom (UK, Central Drugs Coordinating Unit, 1998), continental Europe (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, 1997) and the United States (US, National Institute on Drug Abuse, 1997). In the UK, data fron recent population surveys show that some 50'% of young people between the ages of 16 and 24 years have used an illicit drug (Ramsay & Spiller, 1997; Health Education Authority, 1997). The life-time prevalence of cannabis use among 16-19-year-olds in Britain is estimated to be 35%, and use of the so-called 'dance drugs', ecstasy, amphetamines and LSD, is 9%, 16% and 10%, respectively. For 20-24- year-olds, life-time prevalence for cannabis rises to 421)/0, with 21% reporting use of am-phetamines, 13"/o ecstasy and 14% LSD (Ram-say & Spiller 1997). In contrast, the prevalence of cocaine use stands at 2% for 16-19-year-olds and 6% for 20-24-year-olds. Use of heroin is reported by 1% or less of people aged 16-24 years. Thesc data are generally comparable with estimates from other European countries (Eu-ropean Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, 1997) and the US (Johnston, O'Malley & Bachman, 1997).

A concerted effort has been made to develop aetiological models of substance involvement among young people with some application to prevention and education programmes (see Let-tieri, Sayer & Pearson, 1980; Petraitis, Flay & Miller, 1995, for discussions). One approach has viewed young people as essentially passive and vulnerable to influences in their social environ-ment which may encourage substance use (e.g. Elliott, Huizinga & Ageton, 1985; Elliott, Huizinga & Menard, 1989). From this perspec-tive friends (peers) are thought to exert pressure on a young person to conform to group norms and substance use preferences. Consequently, some prevention programmes have attempted to train young people in the skills needed to resist "peer pressure" (Bureau of Justice Assistance, 1988; Whelan & Culver, 1997). However, while research has consistently found a strong associ-ation between peers and individual behaviour, the nature and direction of this relationship has not been studied in detail and is somewhat con-troversial (Kandel, 1985; Coggans & McKellar, - 1994; Bauman & Ennett, 1996). Another aetio-logical perspective has sought to identify factors which protect young people from or propel them towards using substances. For example, Epstein et aL (1995) proposed that good communication and assertiveness skills are protective factors which help an individual to decline an oppor-tunity to take a substance in a social situation. In this study, links were found between individuals having high self-efficacy for life skills and a lower likelihood of experimentation with cannabis. A range of risk factors have also been suggested, including impaired emotional control (Jessor & Jcssor, 1977), low achievement at school (Brook et al., 1986) and family conflict (Robins, 1980).

A contrasting approach, broadly influenced by psychological theories of health behaviour de- cision-making (e.g. Langer & Warheit, 1992; Ajzen, 1985,1988), sees young people as mak-ing an active appraisal of the personal benefits and costs from using substances. Here, research has tended to focus on alcohol, tobacco and, to a lesser extent, cannabis. Many studies have explored the reasons and motivations which young people cite for using a substance (Car-man, 1979; Butler, Gunderson & Bruni, 1981; Newcomb et aL, 1988; Cato, 1992; McKay et al., 1992). Some reports have described both personal reasons for use (e.g. because of negative mood) and social motives (e.g. to have a good time with friends) (Haden & Edmundson, 1991). Others have identified more detailed cate-gories including: positive/negative affect, social/ recreation, compulsive use, drug-effeet, tension reduction and peer-influence (Segal, Huba & Singer, 1980; Segal et aL, 1982; Segal, 1985-86; Johnston & O'Malley, 1986; Newcomb et aL, 1988). A limitation of much of this work has been the grouping of all illicit substances to-gether or a simple distinction between cannabis and an unspecified global category labelled "hard drugs". However, Johnston & O'Malley (1986) were able to differentiate between reasons for use of alcohol, cannabis, LSD, amphetamines, tran-quilizers, cocaine and opioids in young Ameri-cans. Their findings suggested that these reasons vary across the type of substance and the extent of an individual's prior experience. Another study showed that the perceived physical and psychological effects of cannabis were more powerful predictors of continued use than the perceived social benefits (Bailey, Flewelling & Rachal, 1992).

The influence of negative effects from taking a substance (e.g. anxiety, hangover) on future con-sumption patterns has received little attention from research. Despite the emphasis placed by prevention programmes on highlighting negative experiences, there is little evidence that this helps to deter future use (Huba, Newcomb & Bender, 1986).

In the UK to date, there has been only limited exploration of the relative importance of personal and social factors on substance use involvement and future intentions. Little practical infor-mation has been, gathered to guide education programmes which distinguish between different types of substances. In consequence, we sought to conduct a focused, small-scale study of young people who have had some experience of using different substances. We considered that a fo-cused study design would be an economical and efficient means of exploring these issues and for generating formal hypotheses for testing in a larger sample. l'he objective of the study was to explore relationships between individual and peer substance involvement, the reasons or per-ceived functions for using different substances, the experience of negative effects and futurc substance use intentions.

Method

Measures

Data were gathered from a researcher-adminis-tered interview of approximately 30 minutes' duration. Life-time use of tobacco, heroin, co-caine hydrochloride, crack cocaine and LSD was recorded. For alcohol, cannabis, amphetamines and ecstasy—the substances which arc most commonly used in this population—the fre-quency (total number of days used) and typical quantity (intensity) of consumption on a using day in the 90 days prior to interview was assessed (see Marsden et aL, 1998). Prompt cards were uscd to assist recall for frequency of consump-tion while typical daily quantity was recorded verbatim.le reliable measurement of the in-tensity of illicit drug use from self-reports is acknowledged to be problematic and self-reports were taken to be a proxy for the true dosage. Respondents were asked to estimate the pro-portion of their friends who were likely to use each substance within the next 6 months (as a indicator of perceived peer drug involvement) using a five-point scale (none-all), and also the likelihood that they would themselves use in the next 12 months, using a seven-point scale (very unlikely-very likely).

We developed three scale measures for the interview. A three-item Mood Function scale assessed the frequency of using a named sub-stance in the past year to: (a) "make yourself feel better when you were low or depressed"; (b) "to help you to relax"; and (c) "to help make an everyday activity less boring". A five-item Social/ Contextual Function scale assessed the fre-quency of using named substances to: (a) "help you to feel more confident in a social situation"; (b) "help you to let go of inhibitions"; (c) "help you to keep going on a night out with friends"; (d) "enjoy the company of your friends"; and (e) "help you to feel closer to someone". A three- item life-time Negative Effects/events scale also assessed for each substance how often the re-spondents had ever "felt sick or unwell"; "taken more or a stronger dose than you would have liked to" and "wished the effects would reduce or stop". Responses to the three scales were recorded using a five-point scale (never- always). It should be noted that the function scales are measures of behaviour (i.e. the recalled fre-quency of using a substance) and are therefore distinct from expectancy scales which measure beliefs.

An initial pool of 10 items for the Mood Function scale and Social/contextual function scales was derived from the relevant literature and from qualitative interviews with a separate sample of 10 young people (aged 16-21 years), who had recently used two or more of the target substances. Two items were discarded after pi-loting. The pool of four items for the Negative Effects scale was developed in a similar manner, with one statement being discarded after pilot-ing. Prior to data collection, the items were randomly ordered. Scale scores were subse-quently computed by summing the responses for each item and dividing by the number of items.

Sampling and recruitment

One hundred respondents were recruited from Southern England using snowballing interview techniques with nine starting points. Interview starting points included a waitress, a university student, a drug seller and a college student. This recruitment technique is believed to be an effec-tive way of generating samples from hidden population whcre no formal sampling frame is available (Van Meter, 1990). The sampling pro-cedure was designed to recruit individuals whose experience of substance use was in excess of national norms for this age range. Sampling was not therefore intended to yield a representative group of young people in this. age range. All interviews were conducted in informal com-munity settings.

Results

The sample

One hundred young people were interviewed (45 females). Their average age was 18.8 years (range 16-21). The majority (n = 74) described themselves as "white European"; 17 reported their ethnic origin to be "African-Caribbean" or "black British", six as "Asian" and three as "mixed race". Thirty-seven respondents lived with their parent(s); 21 were living in temporary hostels or were of rangexed addrcss and 42 were in rented accommodation. Most of the sample (n = 69) were ismoked form of eoneation at the time of interview; 16 had full-time work and 15 were. formally unemployed.

A wide rangc of life-time substance use was reported. All respondents had used alcohol, 94 had smokcd at least onc cigarette and 89 re-ported using cannabis. For the other six sub-stareportedessed, life-time uusewas as follows: illicit amphetamines (n.= 56), ecstasy (n = 38), LSD (n = 35), heroin (n = 13), illicit opioids (n = 5) and illicit benzodiazepines (n = 6). Six respondents rcportcd intravenous drug usc at some point in their lives and two were current injectors. None of the participants reported pre-vious treatment for substance use. Life-time polysubstance use was common: the mean num-ber of different substances ever used (excluding cigarettes) was .3.4 (range 1-8). There were no differences in life-time prevalence between mthes and females. The remaining analyses concern the four target substances (alcohol, cannthes, am-phetamines and ecstasy) selected for detailed investigation.

Substance use patterns

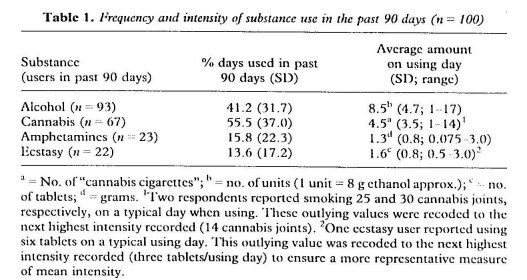

Table 1 summarizes thc frequency and typical intensity of consumption for the four target sub-stances during thc 90 days prior to interview. There were no observed differences in the frequency of substance use between males and fe-males. Gender differences in the average intensity of use were observed for alcohol and cannabis only. Males reported smoking 5.6 can-nabis joints on a typical day (range 1-14) and females reported smoking 2.5 cannabis joints (range 1-8) (t1641 = 3.87, p< 0.0001). For al-cohol, male diinkers consumed an average of 9.5 standard unitthen a typical using day (range 2-17 units) in contrast with females, who drank an average of 7.2 units (rangc 1-16 units) (ti901= 2.42, p < 0.05).

Pearson's product—moment correlation coefficients for thc age of the respondent and the frequency of use of cigarettes, alcohol, cannabis and ecstasy in the past 90 days averaged 0.16 in absolute value across thc four substances. Pair-wisc comparisons were non-significant (p > 0.05) with the exception of amphetamines (r = 0.65, p < 0.001). There were no statistically significant correlations betweenthee age of the respondent and the intensity of use.

Functions, negative effects and use

Chronbach's alpha coefficients across thc users of alcohol, cannabis, amphetamines and ecstasy averaged 0.72 for thc Mood Function scale, 0.80 for the Social/Contextual function scale and 0.78 for the Negative Effects scale. Scores on the Mood Function and Social/Contextual funfrcimscales were significantly correlated for all four substance types (the average of the intcrscale correlations was .0.55; p=0.01 or less). The Negative Effects scale was statistically indepen-dent frcirn the two functions scales with the exception of alcohol, where the correlation be-tween this and thc Social/Contextual function scale was 0.22 (p< 0.05).

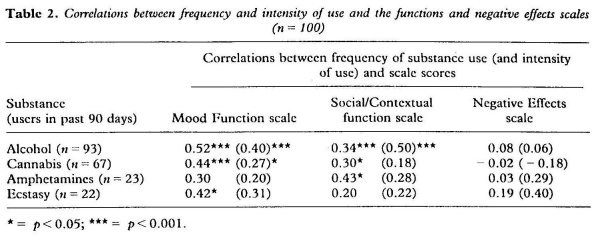

The scale scorcs were then correlated with the frequency and intcnsity of substancc use in thuse.st 90 days (Table 2). The average correlation for the Mood Function scale and frequency of use for the four substanccs was 0.42. Higher scorcs on this scale were associatcd with more frequent usc of alcohol, cannabis and ecstasy in the 3 months prior to interview. With the excep-tion of ecstasy, correlations for the Social/Con-textual scale also suggested that there was a tendency for higher scores to be associated with more frequent usc. For the typical intcnsity of use, correlations between the average number of units of alcohol consumed on a typical drinking occasion and both the Mood Function scale and Social/Contextual function scales were significant (p < 0.001 for both). The average in-tensity of cannabis smoking was also found to correlate significantly with the Mood Function scale (p < 0.05) but not with thc SociaUContex-tual function scale.

Many respondents reported experiencing negative effects from thcir life-time consumption of the four substances. These were most com-monly reported for alcohol. Mean scores on the Negative Effects scale (rangc 0-12) were as fol-lows: alcohol = 6.1; cannabis = 2.9; ec-stasy -= 2.8; amphetamines = 2.8. In contrast to the function scales, correlations between fre-quency of recent use and thc negative effects scale were low (averaging 0.08 in absolute mag-nitudc) and were non-significant. Correlations between intensity of use and the negative effects scale were also low (averaging 0.23 in absolute magnitude, NS). Correlations between the mea-sure of perceived current peer drug involvement and both the frequency and werecal intensity of cannabis use were significant (r 0.36; p < 0.01 and r -= 0.28; p <0.05, respectively). The per-ceived extent of peer use of alcohol correlated with the frequency of use (r= 0.30; p < 0.01), but not the usual intensity of use (r = 0.13; NS). Correlations between perceived peer drug in-volvement and the frequency and intensity of ecstasy use (r -= 0.38; NS; r = 0.41; NS) and amphetamine use (r = 0.12; NS; r = 0.38; NS) wcrc also non-significant.

Future substance use intentions

We then sought to explore the relationships be-tween the function scales, perceived peer in-volvement and the respondents' substance use intentions. Specifically, the ability of the Mood Function, Social/Contextual function and Negative Effects scales to predict the perceived likeli-hood of future use for each substance was assessed. Correlations between scores on the Negative Effects scale and the likelihood of using each substance were low (averaging 0.09 in ab-solute value) and were non-significant. This scale was therefore excluded from further analy-sis.

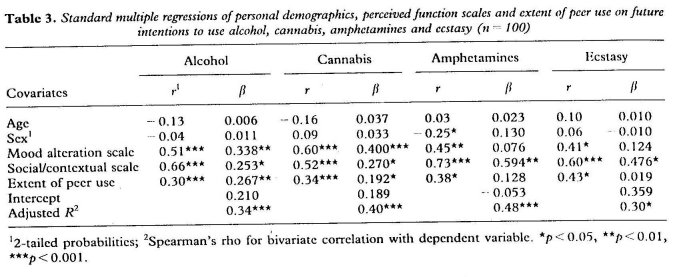

Separate standard multiple regressions analyses (in which all covariatcs were entered simul-taneously) were performed. The perceived likelihood of using each substance in the next 12 months was the dependent variable and age, sex, the Mood Function and Social/Contextual func-tion scores and the extent of peer involvement were covariates. The cases to covariates ratio for these analyses ranged from 31:1 to 7:1 (ecstasy), exceeding the minimum ratio considered acceptable for multiple regression analysis (Tabachnick & Fidell, 1989). The results are shown in Table 3.

Subjects' age and sex did not make significant contributions to any of the regression equations. For alcohol, 34% of the variability in future intention to drink again was predicted from strongeres on thc three covariates. A similar result for cannabis was observed. Here, 40%accountedaria-bility in intcntion scores was prcdictcd by thethevariates, with the Mood Function score exert-ing a relatively stronger predictive effect (fl = 0.400) than the other covariates. A different result emerged from thc analysis of the intcn-tions to usefocusedy and amphetamines. For ec-stasy, the Social/Contextual function scale was the only significant predictor (11 = 0.476). A similar and somewhat strongcr result was seen for amphetamines, with 4 8 °/o of the variability in intentions accountcd for, with the Social/Con-textual function score as ththesee significant pre-dictor (II= 0.594).

Discussion

This paper has explored the personal and social influences on substance use and intentions to use in a sample of 16-21-year-olds. Data collection focuscd on thc respondents' perceived functions for their use, the life-time experience of negative effects, the extent of peer iuse.vement andweuture use intentions. Our results provide evidence that substance consumption by young people can serve specific mointensityng and social usections and that thcsc may prove useful in predicting their intentions to use again in the future. The results also call into question the extent to which negative effThes from drug use directly influence subseducationug-related behaviours.

A common approach in drug prevention in the UK has been tuse.ghlight the potential negative effects from usc. However, wc found that in our sample correlations betweenthoselife-time experi-ence of negative effects and the frequency and intcnsity of substance usc were low. It appears that for this group of young people, negative experiences arising from substance use had not been sufficient to discourage future consump-tion. Thc implications from these data arc ththecducation and prevention programmes may be strengthened by using new approaches to deter usc. However, since our questionnaire recorded life-time prevalence of negative effects, it is poss-ible that thosc that were reported had been ex-perienced some time ago. In such cases, use might have been modified soon aftenon-signifieantences in order to avoid similar consequences in the future.

Drug use has a long history of being linked to influences exerted by thc indiVidual's peer group. We measured thc perceived extent of pccr sub-stance involvement and examined its relationship with consumption patterns in our sample. The results showed that this variable was significantly correlated with thc respondents' frequency and typical intensity of cannabis usc and their fre-quency of drinking alcohol. A positive but non-significant association was also found between peer and individual use of amphetamines and ecstasy. This is perhaps unsurprising, as the use of both alcohol and cannabis could bc described as a social activity in itself. In contrast, the use of amphetamines and ecstasy, while often occurring in a social context, is more likely to be associated with additional activity 'such as dancing.

From the results of our regression analyses it appears that the perceived likelihood of taking a substance in the future may be understood in terms of the functions served by its use. For cannabis and alcohol, perceived mood alteration and social/contextual ftmctions, together with the extent of peer involvement predicted inten-tions to use. For amphetamines and ecstasy, our analyses suggested that there may be a tendency for socialicontextual, but not mood altering functions to be more influential on future use.

Overall, our findings support the recommen-dation that educators and prevention programme planners should recognize the complexity of the reasons behind substance use and then encour-age young people to seek alternative ways of fulfilling them (Newcomb et aL, 1988; Boys et al., in press). However, we suggest that research should focus more on measuring the perceived functions for use in contrast with more general-ized reasons for use. This approach could yield data leading to more specific suggestions for alternative ways for fulfilling individual and so-cial functions (which do not involve drug tak-ing). Additionally, profiling the functions for the use of different drugs might help to predict which substances are likely to be substituted for one another (Boys, Marsden & Griffiths, 1999).

Assessing the specific functions for substance use among young people may prove to be an important new territory for prevention research. This approach could help to predict whether a substance is used on a regular basis after exper-imentation and may also contribute to the mod-elling of other aspects of substance-related decision-making. Overall, it appears from the present study that different substances fulfil dif-ferent functions for the young consumer. If these results are confirmed in larger-scale studies, it suggests that educational and preventative efforts need to recognize these functional lifferences and tailor their content accordingly.

Acknowledgements

The research described in this paper was sup-ported by funding from the Health Education Authority (HEA). The views expressed are those of the researchers and are not necessarily those of the HEA. The authors also would also like to

express their thanks to the Wates Foundation for their support on earlier work.

References

AZJEN, I. (1985) From decisions to actions: a theory of planned behaviour, in: Kum., J. & BECKMANN, J. (Eds) Action-control: from cognition to behaviour, pp. 11-39 (New York, Springer).

AZJEN, I. (1988) Attitudes, Personality and Behaviour (Homework, IL, Dorscy Press).

BAILEY, S. L., FLEWELLING, R. L. & RActini., J. V. (1992) Predicting continued use of marijuana among adolescents: the relative influence of drug-specific and social context factors, jouriza/ of Health and Social Behavior, 33, 51-66.

BAUMAN, K. E. & ENNETT, S. T. (1996) On the im-portance of peer influence for adolescent drug use: commonly neglected considerations, Addiction, 91, 185-198.

BOYS, A., MARSDEN, J. & GRIFI7ITHS, P. (1999) Read-ing between the lines: is cocaine becoming the stimulant of choice for urban youth? Druglink, Jan/ Feb, 20-22.

BOYS, A., MARSDEN, J., FOUNTAIN, J., GRIFFITHS, P., STiliwELL, G. & STRANG, J. (1999) What influences young people's use of drugs? A qualitative study of decision-making, Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, in press.

BROOK, J. S., WHITEMAN, M., GORDON, A. S. & CO-HEN, P. (1986) Dynamics of childhood and ado-lescent personality traits and adolescent drug use, Developmental Psychology, 22, 403-

BUREAU OF JUSTICE ASSISTANCE, US DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE: (1988) Implementing Project DARE: drug abuse resistance education (Washington, DC, Bureau of Justice Assistance).

BUTLER, M. C., GUNDERSON, E. K. E. & BRUNI, J. R. (1981) Motivational determinants of illicit drug use: an assessment of underlying dimensions and their relationship to behaviour, International Yournal of the Addictions, 16, 243-252.

CARMAN, R. S. (1979) Motivations for drug use and problematic outcomes among rural junior high school students, Addictive Behaviors, 4, 91-93.

CATO, B. M (1992) Youth's recreation and drug sen-sations: is there a relationship? journal of Drug Edu-cation, 22, 293-301.

CENTRAL DRUGS COORDINATION UNIT (1998) Tackling Drugs to Build a Better Britain, the government's 10- year strategy for tackling drug misuse, (London, Sta-tionery Office).

COGGANS, N. & McKELLAR, S. (1994) Drug use amongst peers: Peer pressure or peer preference? Drugs: Education Prevention and Policy, 1, 15-26.

EUROPEAN MONITORING CENTRE FOR DRUGS AND DRUG ADDICTION (1997) Annual Report on the State of the Drugs Problem in the European Union (Lisbon, EMCDDA).

EPSTEIN, J. A., BOTVIN, G. J., DIAZ, T., TOTH, V. & SCHINKE, S. P. (1995) Social and personal factors in marijuana use and Intention to use drugs among inner city minority youth, Developmental and Be-havioural Paediatrics, 1, 14-20.

ELLIOTT, D. S., HulziNGA, D. & MENARD, S. (1989) Multiple Problem Youth: delinquency, substance use and mental health problems (New York, Springer-Verlag).

ELLIOTT, D. S., HUIZINGA, D. & AGET0N, S. S. (1985) Explaining Delinquency and Drug Use (Beverly Hills, CA, Sage).

HADEN, T. 1.. & EDNiuNDsoN, w. 0991) Personal and social motivations as predictors of substance use among college studcnts, journal of Drug Education, 21, 303-312.

HEALTH EDUCATION AUTHORITY INTERNATIONAL (1997) Drug Use in England: results of the 1995 National Drugs Campaign surve_y (London, Health Education Authority).

HURA, G. J., NEwcomn, M. D. & BENTLER, 1'. M. (1986) Adverse drug experiences and drug use be-haviors: a onc-ycar longitudinal study of adolescents, journal of Paediatric Psychology, 11, 203-219.

JEsson, R. & Jiisson, S. L. (1977) Problem Behavior and Psychosocial Development: a longitudinal study of youth (San Diego, CA, Academic Press).

JOHNSTON, L. D. & O'MALLEY, P. M. (1986) Why do the nation's students use drugs and alcohol? Self reported rcasons from nine national surveys, journal of Drug Issues, 16, 29-66.

JOHNSTON, L. D., O'MAILE.v, P. M. & BACHMAN J. G. (1997) National Survey Results on Drug Use from the Monitoring the Future Study, 1975-1996; secondary school students (Rockville, MD, US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute on Drug Abuse).

KANDEI., D. B. (1985) On processes of peer influences in adolescent drug use: a developmental perspective, Advances in Alcohol and Substance Abuse, 4, 139-163. LANGER, L. M. St WARHEIT, G. J. (1992) The pre-adult health decision-making model: linking decision-mak-ing directedness/orientation to adolescent health re-lated attitudes and behaviours, Adolescence, 27, 919-948.

LETIERI, D. J., SAYER, M. & PEARSON', H. W. (1980) Theories on Drug Abuse: selected contemporary perspec-tives, NIDA research monograph 30 (Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office).

MARSDEN, J., Gossor, M., STEWART, D. et at (1998) The Maudslcy Addiction Profile (MAP): a brief instrument for assessing treatment outcome, Addic-tion 93, 1857-1867.

McKay, J. R., Muttinfv, R. T., mcGuiRE, J., RiviNus, T. R. & MusTo, S. A. (1992) Incareerated adoles-cents' attributions for drug and alcohol use, Addic-tive Behaviours, 17, 227-235.

NATIONAL. INSTITUTE: ON DRUG ABUSE (1997) Prevent-ing Drug Abuse Among Children and Adokscents (Rockville, MD, National Institutes of Health Publi-cation).

NEwcomb, M. D., Cliou, C-P., BENTLER, P. M. & Hum, G. J. (1988) Cognitive motivations for drug use among adolescents: longitudinal tests of gender differences and predictors of change in drug use, Journal of Counselling Psychology, 35, 426-438.

PERTRAitis, J., FLAY, B. R. & T. Q. (1995) Reviewing theories of adolescent substance use: or-ganizing pieces in the puzzle, Psychological Bulletin, 117, 67-86.

RAmsAy M. & SMILER, J. (1997) Drug Use Declared irr 1996: latest results from the British Crime Survey (Lon-don, Home Office).

Robins, L. N. (1980) The natural history of drug abuse, Acta Psychiatrica Scandanavica, 62 (suppl. 284), 7-20.

SEGAL, B., HURA, G. J. St SINGER, J. L. (1980) Reasons for drug and alcohol use by college students, Inter-national journal of the Addictions, 15, 489-498.

SEGAL, B., CROMER, F., Honrou, S. & WASSERMAN, P. (1982) Patterns of reasons for drug use among de-tained and adjudicated juveniles, International jour-nal of the Addictions, 17, 1117--1130.

SEGAL, B. (1985-86) Confirmatory analyses of reasons for experiencing psychoactive drugs during ado-lescence, International journal of the Addictions, 20, 1649-1662.

TABAchnick, B. G. & Flim:11., L. S. (1989) Using Mul-tivariate Statistics, 2nd edn (New York, Harper Collins).

VAN METER, K. M. (1990) Methodological and design issucs: techniques for assessing the representatives of snowball sainples, in: LAmstiicr, E. Y. (Ed.) The Collection and Interpretation of Data front Hidden Pop-ulations, pp. 31-33 (Rockville MD, National Insti-tute on Drug Abuse).

WHELAN, S. & CULVER, J. (1997) 'Don't say "no", sa_y DARE'? Summaty of an outcome evaluation of a Drug Abuse Resistance Education programme in Mansfield (Nottinghamshire, North Nottinghamshire Health Promotion).

Correspondence to: Annabel Boys, National Addiction Centre, Maudsley Hospital/Institute of Psychiatry, 4, Windsor Walk, London, SE5 8AF, UK. Tel: 0171 919 3804; e-mail: This e-mail address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it