Synthesis of Qualitative Research on Drug Use in the European Union

Drug Abuse

Synthesis of Qualitative Research on Drug Use in the European Union: Report on an EMCDDA Project

Edited by Jane Fountain Paul Griffiths

National Addiction Centre (NAC), London, UK, for the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), Lisbon, Portugal

This paper is an edited version of the report 'Inventory, Bibliography and Synthesis of Qualitative Research in the European Union' which is based on the work of the following: Richard Hartnoll, Julian Vicente (EMCDDA); Sabine Haas, Alfred Uhl (Austria); Fabienne Ha-riga, Pierre de Plaen (Belgium); Karen Ellen Spannow, Mads Uffe Pederson (Denmark); Pekka Hakkarainen, Aarne Kinnunen (Finland); Rodolphe Ingold, Marijo Taboda (France); Uwe E. Kemmesies (Ger-many); Anna Kokkevi (Greece); Aileen O'Gorman, Barry Cullen, Shane Butler (Ireland); Annette Verster, Letizia Paoli, Paolo Stocco (Italy); Alain Origer (Luxembourg); Peter Blanken, Dirk J. Korf, Ton Nabben (Netherlands); Juan F. Gamella, Nuria Romo, Arturo Alva-rez Roldan, Aurelio Diaz (Spain); Ingrid Lander (Sweden); Tim Rhodes, Linda Cusick, Howard Parker, Mick Bloor (UK); Louisa Vin-goe, Loraine Bacchus, Nicola Dominy (NAC); Mike Agar (USA).

Key Words

Qualitative research • Drug use • European Union

Abstract

This paper is a synthesis of the information in the report Inventory, Bibliography and Synthesis of Qualitative Re-search in the European Union which was co-ordinated for the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, Lisbon, Portugal, by the National Addiction Centre, London, UK. It is based on the work of a network of qualitative researchers from the European Union. The report includes detailed information from each member state on current qualitative projects, relevant publications from the last 10 years and a directory of those researchers active in this area. The paper introduces the project, outlines its future direction and discusses what can be defined as 'qualitative research'. Historical devel-opments and the role of qualitative methodology in rela-tion to research into drug use are examined. A summary of the project's findings is presented, and the relevance of qualitative research for policy-making is discussed. Finally, the methodology used to collect data for the project is described.

Background

The European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) recognises the importance of supporting the development of research methods for understanding patterns of drug use and the social processes involved in the use of drugs. Qualitative research is essential for interpreting statistical data and placing it in con-text, for providing insight into the problems and needs associated with a range of drug-using patterns, for assessing which types of interventions may be more relevant and for helping to evaluate the impact of those interventions on drug users. In 1996, the EMCDDA launched a project to obtain a comprehensive and detailed picture of qualitative research on drug use in the European Union (EU), producing an inventory of current projects, an annotated bibliography of published and 'grey' literature from the last decade and a directory of researchers. As part of the project, a seminar was held in Bologna: participants were chosen to include those who were well in-formed on the relevant issues at local, European and global levels, from both a practical and theoretical viewpoint. The project was co-ordinated by the National Addiction Centre (NAC), London, UK.

Increasing attention has been focused on developing comparable methodologies across the EU and supporting the development of human networks to further these activities. To date, such activity has tended to focus on quantitative methodologies, such as the harmonisation of survey data sets and treatment reporting systems. Such work is critical to the ability to monitor the use of illicit drugs and to provide policy-makers with a sound basis for identifying appropriate responses. However, the develop-ment of an understanding of patterns of drug consump-tion and their relationship to health and social problems is a complex process. This understanding is only possible if informed by data collected using a diverse set of method-ological techniques: quantitative data are never likely to be sufficient unless informed and supported by detailed qualitative inquiry, but, to date, qualitative research re-mains a relatively neglected area in terms of EU networking activity. To some extent this may be due to issues inherent to the methodology itself, as the techniques designed to produce a detailed understanding of specific contexts do not easily lend themselves to methodological standardisation. Nevertheless, on a broader level, there is much to be gained by the dissemination of insights obtained by qualitative studies and by developing human networks of those engaged in this kind of endeavour. In addition, methodological and theoretical advances are most likely to be achieved if supported by an active research community in which good communication links exist between researchers investigating similar topics within their own countries.

The central aim of the project, therefore, was to pro-duce a comprehensive and detailed picture of qualitative research on drug use in the EU, with the focus on publica-tions from the last 10 years, studies currently in progress and those researchers who use qualitative methods. The project also aimed to highlight the areas likely to be fruit-ful for future activity, both within each country and on a collaborative, EU-wide basis. It is intended that the report on the project be used as a resource to facilitate closer col-laboration of countries on qualitative research projects and to identify those areas which are likely to be common priorities for future investigation.

Future Developments

The EMCDDA is maintaining support for improving qualitative research across the EU and at the end of 1997 launched a new project, 'Co-ordination of working groups of qualitative researchers to analyse different drug use patterns and the implication for public health strategies and prevention', which will continue and expand the activities begun in 1996. This project is also co-ordinated by the NAC, London. The objectives are to consolidate the network of qualitative researchers and update the report Inventory, Bibliography and Synthesis of Qualita-tive Research in the European Union [1] after further dis-semination, discussion and refinement. Working groups have been established to produce state-of-the-art reviews on key qualitative topics: new drug trends, the drugs-crime relationship and injecting risk behaviour. These reviews will be designed to provide policy-makers with a sophisticated overview of the key issues in each area. In addition, this project has set up an Internet site (www.qed.org.uk) to promote networking and discussions on qualitative themes and assist with the development of qualitative research in those countries in which this tradition is lacking, by encouraging participation in networking activities.

Towards a Definition of Qualitative Research

The issue of defining qualitative research has been the subject of much debate (see, for example, Denzin and Lin-coln [2] or Lambert et al. [3]), and there is a vast field of literature on qualitative methodology which discusses, for example, data collection and analysis techniques, theoret-ical concepts and the relationship between the researcher and the researched. Nevertheless, Denzin and Lincoln [2, p. 2] offer a useful generic definition:

Qualitative research is multimethod in focus, involving an inter-pretative, naturalistic approach to its subject matter. This means that qualitative researchers study things in their natural settings, attempting to make sense of, or interpret, phenomena in terms of the meanings people bring to them. Qualitative research involves the studied use and collection of a variety of empirical materials — case study, personal experience, introspective, life story, interview, observation-al, historical, interactional and visual texts — that describe routine and problematic moments and meanings in individuals' lives. Ac-cordingly, qualitative researchers deploy a wide range of interconnected methods, hoping always to get a better fix on the subject matter at hand.

The definition of what constitutes qualitative research in a European context and which should therefore be included in the project is complex, as many studies have employed a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods. The project has made significant progress in the development of a model of identification by summarising publications according to, for example, sample generation and key findings. Such a strategy will allow a clearer debate on what constitutes the boundaries of qualitative inquiry.

The discussion regarding which studies to include in the project led to a consensus from key qualitative experts from throughout the EU which was that, in some respects, the debate was artificial and that the most useful strategy is not to be overly restrictive in the definition of what con-stitutes 'qualitative'. Studies have therefore been included that appear to have a significant qualitative component: when this has been in doubt, we erred on the side of inclusion.

For the purposes of the project, the following research on drug use (excluding that on alcohol and/or tobacco only) was deemed to be qualitative:

— studies with a significant qualitative component in data collection and/or analysis, including commentar-ies on policy, law, media coverage of drug use, etc.;

— descriptive studies of hidden populations;

— studies describing life-styles, processes and meanings;

— literature describing qualitative methodologies. Excluded were:

— population and other surveys with structured question-naires;

— statistical analyses and presentations of results.

Such a strategy was particularly appropriate when con-sidering those countries which have little tradition of research using qualitative methodology. In addition, it was felt that premature exclusion of publications, projects and personnel which did not fit stricter criteria than those employed may have resulted in a corresponding exclusion of potential future collaborators and research themes. We therefore tried to be as inclusive as possible whilst compiling the project report and hope that the resulting docu-ment does justice to the rich and diverse range of qualita-tive studies conducted across the EU. We attempted to be as comprehensive as possible in our audit, but any such endeavour is unlikely to achieve total coverage. The project report will be updated in late 1998, when it is hoped that omissions can be rectified.

Historical Developments of Qualitative Research in the EU: Overview

The defining period for both qualitative methodology and social interactionist research is usually cited as being the 1920s and 1930s, with the emergence of the 'Chicago School' and its emphasis on the 'situated' nature of action and interpretation. Early qualitative studies in the field of illicit drug use were not only of note for the social explana-tions for drug use and addiction they provided, but also for the developments they made in sociological theories of deviance and in the application of qualitative methods. Thus not only have qualitative methods provided drug researchers with a valuable method of scientific inquiry, but the field of drug research has proved valuable in the development of qualitative methods (see, for example, Silverman [4]).

However, in the EU — as elsewhere — these methods have not been wholeheartedly embraced by researchers and funding bodies, although the pace of the development of significant qualitative research into drug use across the EU has varied immensely from country to country. In some countries, this can be partly explained by a paucity of any research into drug use, whatever the methodology: for example, the UK has had a strong tradition in this respect, whilst research into drug use in Ireland has begun only rel-atively recently and in Greece is in the early stages of devel-opment. Some countries have taken only tentative steps towards a qualitative input into studies of drug use, and little importance has been attached to behaviours taking place in a 'natural' context such as on the street, in clubs, at dealing locations and amongst networks of drug users. Thus the qualitative element of a study may be restricted to a focus group which is seen as efficient, economical and less time-consuming than an ethnography. A further expla-nation for the lack of the development of qualitative research in some countries is that funding strategies tend to support research that will deliver statistics on, for example, the extent of use of a particular drug or the efficacy of dif-ferent treatment programmes. Another explanation is that a country may have an overall weak tradition of qualitative research in the social sciences in general.

In the past decade (the focus of the project), however, it can be said that, overall, there is a receptivity to the use of qualitative methods in the EU. Rhodes and Cusick [5] suggest that this is not indicative of a major shift in the relative status or dominance of 'positivist' and 'interpre-tative' research paradigms but rather reflects the practical as well as methodological utility of qualitative research in understanding and responding to public health and social problems among 'hidden' populations. In recent years, it appears that the increased advocacy of qualitative meth-ods is related more to public health need than to any para-digmatic shifts between quantitative and qualitative modes of inquiry.

Research is stimulated by drug-related 'problems' — whether identified by e.g. the media, health services, gov-ernment or law enforcement institutions — which are usually concerned with the more alarming forms of drug use such as that by young people or injectors. Reaction can — and usually does — take the form of surveys which measure the prevalence of a particular phenomenon to measure its dimensions. There is no overall body defining research priorities in any EU country, so the topics which attract funding vary throughout the Union. However, a significant factor in the development of qualitative re-search in many countries — notably Spain, Germany and the UK — was the public health imperative to reduce HIV infection associated with drug use. This emphasized the need for research methods capable of understanding the social context and meaning of risk behaviours among hid-den or 'hard-to-reach' populations. Qualitative methods have emerged as particularly well suited to studies of drug use and associated health behaviours, and as particularly valuable in the development of community-based pre-vention and health interventions. Thus the impact of HIV infection and AIDS on the research agenda in the last 10 years, and on the focus of qualitative research in particu-lar, should not be underestimated. More recently, in some EU countries, this focus has been widened to include other drug-using risk behaviours such as HCV transmission and co-morbidity.

The Role of Qualitative Research into Drug Use in the EU

In some EU countries — particularly those in which research into drug use has begun relatively recently — prevalence studies are prioritised over qualitative re-search and its attempts to explain how and why particular behaviours occur. However, as Gamella et al. [6] point out, such a viewpoint may be dominated by a very narrow view of what 'qualitative' approaches and methods may offer. The authors add that, providing qualitative studies are methodologically rigorous:

Interpretations and 'narrative' or historical explanations do not have to be incompatible with mathematical or structural formulations. The goal must be to provide valid answers to relevant ques-tions and concerns. The 'meaning' gained by 'dense' narratives and descriptions should not be inconsistent or incompatible with the search for motives, causes and consequences.

The data collected for the project highlight the multi-faceted role of qualitative drug research and its valuable contribution to the understanding of drug-using behav-iour. Rhodes and Cusick [5] usefully synthesise the main themes emerging from the UK published literature on the role of qualitative research, and these can be applied on an EU-wide basis. The authors identify seven overlapping themes to which qualitative methods are suited and a summary is provided here.

1 conducting research among hidden populations;

2 providing descriptive data on the social meanings of drug use;

3 providing descriptive data on the social contexts in which drug use occurs;

4 informing quantitative research designs and methods;

5 questioning quantitative measures and hypotheses;

6 explaining quantitative research findings;

7 informing intervention responses.

Researching Hidden Populations

Qualitative methods are ideally suited for conducting research among hidden or tard-to-reach' populations such as drug users not in treatment, young people initiat-ing into heroin use and those involved in the distribution of illicit drugs. This is particularly the case in situations where the application of quantitative designs is impractical or methodologically undesirable. A key consideration, for example, is gaining access to the study population. The clandestine nature of many forms of illicit drug use introduces problems of access and bias for large-scale surveys or statistically 'representative' sampling techniques. A variety of studies have demonstrated the utility of qualitative social network, snowball and purposive sampling techniques among a variety of drug-using populations, where the trust and rapport gained through fieldwork con-tact not only assists with access and recruitment but also with the collection of detailed data about sensitive top-ics.

Describing the Social Meanings of Drug Use

Qualitative methods, because of their inductive approach to data collection and hypothesis generation, are particularly valuable in describing drug use and associated behaviours from the perspectives of the participants themselves. This enables the 'social meanings' of drug use behaviours to be described as they are understood by drug users.

One key example is the sharing of injecting equipment. While epidemiologically defined as a 'risk behaviour' for HIV transmission, qualitative studies indicate the multi-ple and situated meanings of sharing behaviours from the perspectives of drug users. These studies have highlighted how the sharing of injecting equipment is embedded as part of a wider social dynamic of behaviours communicating trust and reciprocity in interpersonal relationships.

A further example includes the 'indirect' sharing of drug solutions through 'back loading' or 'front loading' and by the shared use of cotton filters. While often func-tioning as part of routine drug use practices, front or back loading may be taken to communicate or symbolise trust (since drug solutions can be equally divided between syringes), and the lending or giving of used filters may be viewed as a 'gift' to friends (since used filters contain a residue of drug solution). In similar ways, qualitative studies have highlighted how the social meanings at-tached to protected and unprotected sex influence the drug users' condom use. Dispensing with condoms, par-ticularly in long-term relationships, may function as a symbolic display of 'trust', 'commitment' and 'love' be-tween partners. Among HIV-positive as well as HIV-nega-tive drug users, the social meanings attached to unpro-tected sex have been shown to be important factors, in addition to perceptions of HIV risk, which influence pat-terns of sexual risk behaviour.

Describing the Social Context of Drug Use

Qualitative methods are particularly suited to describe the 'social situations' and 'social context' of drug use behaviours. In addition to capturing the social meanings participants attach to their behaviours, qualitative research may help to describe the social and physical set-tings in which drug use occurs and the interplay of indi-vidual and social factors which influence patterns of drug use. A variety of studies have illustrated how individual beliefs and behaviours associated with drug use are in-fluenced by wider structural and economic factors, the impact of sociocultural 'norms', interpersonal and sexual relationships, peer group and social network behaviours, and the social, physical and geographical settings in which drug use occurs.

A key emphasis in such studies is an attempt to describe the links between patterns of drug use and the social-contextual factors which influence them. Drug use is recognised as a social activity mediated by social mean-ings which are themselves influenced by the social and situational context, for example, how exogenous or struc-tural factors (e.g. policing, heroin availability) influence the purchasing, dealing and drug use patterns of a heroin network, which in turn interact with the social relation-ships maintained or lost within the network, and how pat-terns and perceptions of ecstasy use are to a large extent socially organised within the social mores of rave and dance club cultures, where the behavioural manifestation of drug effects can be seen to be contextually determined. Similarly, qualitative studies of HIV risk behaviour have described how needle or syringe sharing and condom use are to some extent dependent on the types of social situa-tions and/or interpersonal relationships in which such behaviours occur.

Informing Quantitative Research

Qualitative methods may inform the design and pa-rameters of quantitative measures. A number of qualita-tive studies have emphasised the utility of these methods in identifying and describing drug use practices and risk behaviours associated with drug use. Observations and interviews, for example, have proved invaluable in identi-fying risk practices which may then be included in large-scale survey measures, as well as in describing how quan-titative measures of risk behaviour are understood by drug users. As mentioned above, one key example in-cludes the multiple meanings of 'sharing' injecting equip-ment. While often used as a matter of course in surveys, qualitative work highlights that drug users may have mul-iple understandings of the term 'sharing' which depend on situational and social context as well as the nature of interpersonal relationships with sharing partners. Other examples are the monitoring of, for instance, new drug trends and reactions to new treatment methods so that appropriate questions can be asked in surveys dealing with these issues.

Questioning Quantitative Research

Qualitative data can not only inform the design of quantitative methods and categories, but they may also question the hypotheses, categories and findings of quan-titative research. The inductive paradigm of qualitative and interpretative research may lead to discoveries which challenge preexisting lay and scientific 'common-sense' assumptions which often feed into, and become perpet-uated by, deductive, positivist and quantitative research designs. For example, ethnographic work among female injecting drug users has challenged popular perceptions that women who use heroin do not share conventional notions of motherhood and responsibility, while a variety of studies have illustrated that 'drug use', 'addiction' and drug use 'problems' are variably socially constructed, in part by the methods and paradigms of research.

Explaining Quantitative Research Findings

Qualitative data may help to interpret the meaning of findings from quantitative research. Here it has also been suggested that a combined quantitative-qualitative approach is of most practical and methodological value. It has been demonstrated, for example, that qualitative interview findings may be used to help interpret and substantiate the findings of quantitative surveys and sta-tistical models. Whereas statistical modelling may identify correlational relationships between variables, it does not adequately assess why or how these relationships exist or explain what these associations mean. The triangulation of multiple methods and data sources, and the combined use of quantitative and qualitative meth-ods in particular, enables the researcher to cross-check findings so as to increase the validity of interpretations made. Examples of this include studies of relapse and initiation.

Informing Interventions

A variety of authors emphasise the practical utility of qualitative research in developing and evaluating policy, prevention or legislative interventions. While few studies have incorporated intervention developments alongside research, qualitative methods are increasingly recognised as a necessary component of action-oriented research and evaluation design. Qualitative research can be particu-larly effective in describing the social settings in which an intervention operates and the factors influencing the effi-cacy of intervention implementation, targeting and process.

Overview of Findings

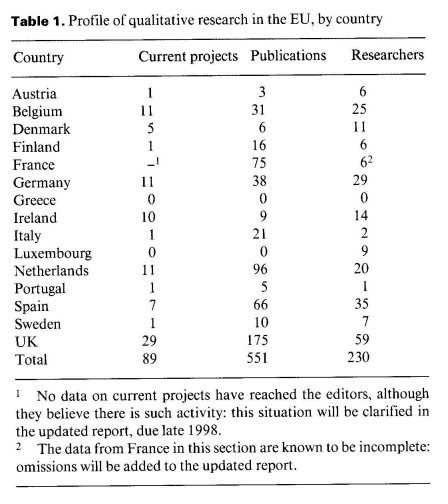

The amount of data which was collected from each country is shown in table 1. It should be noted, however, that whilst the search for current qualitative projects, pub-lications from the last 10 years and researchers was conducted thoroughly, over a period of 9 months, and dis-cussed and validated by key individuals from each mem-ber country, it is possible that some have been over-looked. This is particularly the case of 'grey' literature and its authors. Thus, the data in table 1 — and other presentations of statistics in this section — are a record of the data collected for the project, and comparisons between coun-tries must therefore be made with caution.

As table 1 shows, little qualitative drug research could be identified in some countries. These are also the coun-tries in which drug research in general is poorly devel-oped, probably because, until recently, drug prevalence was low and consequently not seen as a priority area for research investment. In recent years, however, patterns of drug use appear to be converging in Europe, and, although considerable geographical variation is still observable, drug consumption issues are now seen as a priority in vir-tually all EU countries. As such, investment is now being put into the collection of comparable data from across the EU. Even in those countries which have traditionally not invested in drug epidemiology to any great extent, there now appears a greater willingness to engage in such activi-ty, and an acceptance of the importance of compiling such data sets. Encouragingly, during the course of the project, considerable enthusiasm and interest were expressed by such countries.

Some general comments on the extent of qualitative inquiry in the EU can be made from the data in table 1, which shows that the scale of qualitative drug research conducted in the EU varies greatly between countries. In some — notably France, the Netherlands, Spain and the UK — there appears to be a relatively high level of activity, whilst elsewhere — Greece, Luxembourg and Portugal for example — very little qualitative activity could be identi-fied. This observation must be placed into the following context:

— the scale of research into drug use varies greatly across the EU, regardless of the methodology used;

— some countries have very little tradition of conducting qualitative as opposed to quantitative research in any topic area;

— the scale of drug use varies greatly across the EU and in some countries has only recently begun to be seen as a priority area for research activity;

— a strong social science tradition does not exist in some countries, and, historically, central government fund-ing has not been available for research activities.

Summary of Current Qualitative Projects and Published and Grey Literature

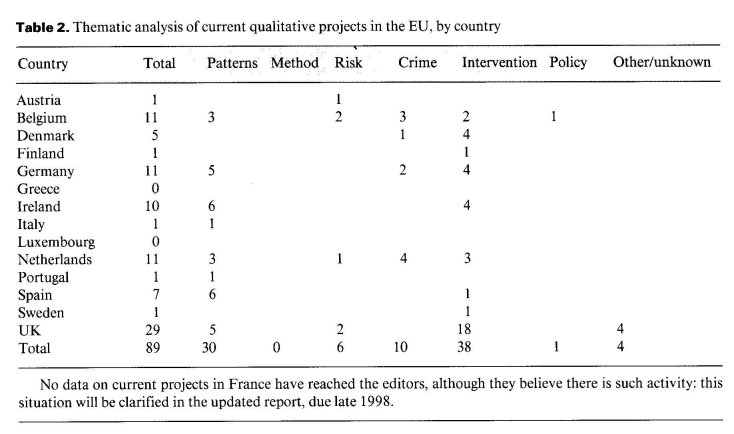

Table 2 presents a thematic analysis of current qualita-tive research in the EU. The data were categorised according to seven broad themes which were identified from an analysis of the literature collected. As was frequently the case, where a project addressed more than one theme, it was categorised according to its major subject. The themes are:

— patterns of use, e.g. life-styles, behaviour and networks, new trends;

— methodology, e.g. sampling, access, analysis;

— risk behaviour and health, e.g. HIV, HCV, HBV, over-dose, injecting, co-morbidity;

— crime, drug markets and other criminal justice issues;

— intervention, i.e. issues surrounding help-seeking, self-help, prevention, treatment and other interventions;

— policy;

— other/unknown.

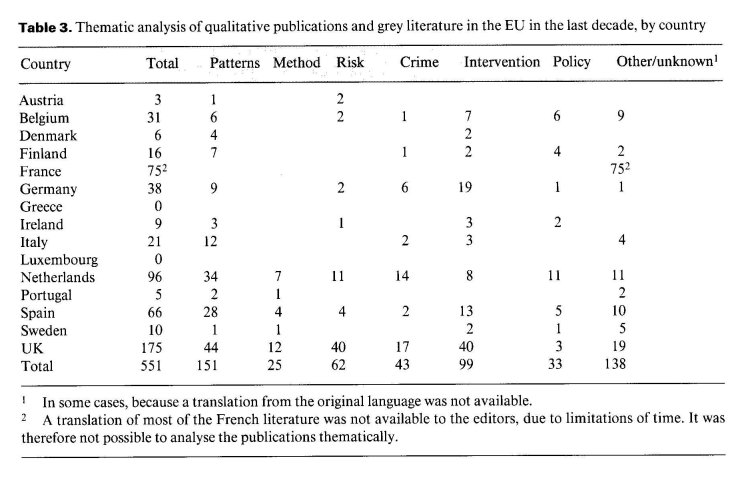

Table 3 presents a thematic analysis of the publications and grey literature located during the course of the project, which were categorised according to the seven broad themes detailed above. As was frequently the case, where a publication addressed more than one theme, it was cate-gorised according to its major subject.

It should be noted that the data in tables 2 and 3 are a record of those collected for the project, and comparisons between countries must therefore be made with caution.

Tables 2 and 3 show that, currently and in the last 10 years, both historical and geographical differences are observable in the kinds of qualitative inquiry which have been conducted across the EU. Whilst health risks associated with injecting populations — particularly HIV risk behaviour — probably accounted for a large propor-tion of qualitative research activity in the late 1980s and early 1990s, more recently studies of new drug trends and drug use by young people have become increasingly popu-lar. In the Netherlands for example, there is a considerable body of work reflecting the relatively sophisticated system for qualitative monitoring patterns of illicit drug use. It is likely that more studies will investigate issues surrounding injecting in the future, as researchers address the challenge of explaining HCV infection rates among drug injectors.

The data in table 2 reveal that the bulk of current qual-itative research activity identified by the project is either concerned with patterns of drug use or addressing some aspect of intervention. In some countries however — particularly Austria, Finland, Greece, Italy, Luxembourg, Portugal and Sweden — few or no current projects could be located.

As table 3 shows, by far the greatest number of publica-tions and grey literature have addressed issues associated with patterns of drug use, which includes the drug use of young people and new drug trends. Risk behaviour and health also constitute a major study theme. Interestingly, much of the literature addressed interventions: usually these were qualitative evaluations of treatment. In Ger-many, Spain and the UK in particular, this theme was evident. Half of all the German qualitative research discovered addressed some aspect of treatment or other intervention.

Two areas in which less publications were detected were those focusing directly on qualitative methodology and policy issues. However, it should not be assumed that studies are not relevant to policy, rather that few qualita-tive studies take policy-making itself as the topic of inqui-ry. This demonstrates the relative sophistication of many qualitative studies which provide commentaries on areas which it would be difficult to address by other means. The absence of more papers addressing methodological issues is perhaps of more concern. Researching patterns of illicit drug use is a complex topic which requires both sophisticated and rigorous methodological procedures. Given that, in some countries in the EU, qualitative methodolo-gy is poorly developed, methodological texts would repre-sent a useful resource. A more general criticism of qualita-tive studies in general might be that they often do not make their methodology explicit.

That said, two other important factors can also be seen to explain the relative paucity of papers on methodological themes. First, if qualitative studies are difficult to pub-lish in general, studies on qualitative methodology alone are likely to be more so, although considerable difficulty is often expressed by those trying to publish methodological papers in general, regardless of their perspective. Second, there is a large body of general literature on conducting qualitative research. It is likely that much of this is rele-vant to research on drug use, but the texts often appear in the social science field in book form rather than compet-ing for the limited space available in specialist drug journals. However, researching patterns of drug use often raises issues that are unique to the topic area: a resource that enabled researchers to discuss and develop qualita-tive methodological approaches would be valuable. In response to this identified need, the second phase of the project — 'Co-ordination of working groups of qualitative researchers to analyse different drug use patterns and the implication for public health strategies and prevention' — will provide a forum for discussions on methodological issues.

Overview of Current Qualitative Research Funding in the EU

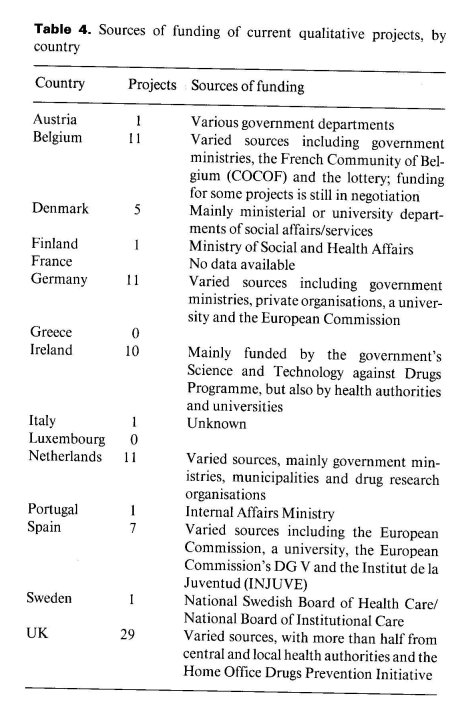

Table 4 gives a brief summary of the sources of funding of the 89 current qualitative research projects on drug use which were identified by the project. It shows that although sources of funding for current projects with a qualitative component vary between countries, overall, government departments and health authorities appear to be the biggest investors. It should be noted, however, that the project was unable to locate little or no current quali-tative research activity on drug use in almost half of the EU countries — Austria, Finland, Greece, Italy, Luxem-bourg, Portugal and Sweden.

Considerable funds are allocated to research on drug use in some countries and the perspective of funders influences not only which aspects of the phenomenon are investigated, but also the methodology of those investigations. If, for example, a funding body sees drug use as largely of a medical or prevalence measurement concern, then the projects funded will reflect that viewpoint and use quantitative methods. However, the contributions made by qualitative research to the understanding of HIV infection amongst injecting drug users have meant that there is a growing acceptance of a multi-method approach to data collection and analysis. This can be seen in table 2, which shows that the majority of current projects which incorporate qualitative methods are investigating pat-terns of drug use and some aspect of intervention, tradi-tionally the domains of quantitative researchers.

No EU country has a central funding body for research into drug use, but in some countries, various initiatives have outlined research priorities and/or made funds avail-able to projects with a qualitative element, for example, the Home Office Drug Prevention Initiative in the UK and the government's Science and Technology against Drugs Programme in Ireland. In the Netherlands, re-search into drug use is about to be financed according to the Framework Program for Research on Addiction, although it is not yet clear how this will affect funding for qualitative research projects. It is encouraging to note that the European Commission has funded collaborative projects in Germany and Spain — each being conducted in five different European cities.

The Relevance of Qualitative Research on Drug Use for Policy-Making in the EU

The data collected for the project show clearly that a substantial body of qualitative research and expertise exists in a few countries, whilst, in others, this is a novel approach. It is also clear that there is untapped potential for bringing this knowledge into the policy domain in the EU, which offers a natural laboratory in which drug use can be examined within different social, cultural and poli-cy contexts. Such an examination reveals the limitations of quantitative research, however. Comparable statistical surveys can be conducted in different countries, but the problem of interpretation remains: what the results mean in the different countries and the implications for policy. It is here that the data from qualitative research are invaluable, as they look in more depth at the links between the different actors, and their contexts, and allow efficient and relevant interactions and interventions to be developed. However, the process which begins with a drug-related problem and ends with the making of deci-sions which aim to solve that problem is not straightfor-ward. A fruitful working relationship between researchers and policy-makers is often hindered by misunderstand-ing: policy-makers may often ask questions to which they have already found political answers, and researchers may give scientific answers to political questions.

The issue of the relationship between research and policy is a key one if research is to have any impact on policy and public health. For instance, HIV, AIDS and HCV amongst drug users remain a substantial problem in many countries, and the responses to it — from both a research and policy formulation point of view — vary considerably from one country to another. In some — such as parts of Germany — there are considerable problems in promoting harm reduction approaches aimed to limit the damage. In others, such as the Netherlands, harm reduction is the principal response to the problems of HIV and other health risks amongst drug users. Ultimately, though, how-ever 'good' the qualitative research, its influence on policy will also be related to many other factors: the political moment, the role of the media, the relationship between the researchers and the policy-makers, the ways findings are managed in their dissemination and whether findings are converted into ideas and interventions which others can easily use in further developing policy and practice.

It is encouraging that, in a number of countries, research activity into drug use seems to be developing. In some respects, this can be seen as corresponding to drug use moving up the agenda of concern of policy-makers. This, together with a realisation that simply relying on sta-tistical data sets is not sufficient to understand the phe-nomenon, has prompted the development and funding of qualitative projects in a number of countries. In general, the development has been prompted by three distinct themes: new drug trends and the drug use of young peo-ple, injecting risk behaviour, and drug use and crime.

New Drug Trends and the Drug Use of Young People

Firstly, and most recently, the increase in drug preva-lence among the general population — especially young people — has prompted the funding of studies that seek to explore how such new trends develop or how young people initiated their drug consumption. The representative drug for this phenomenon is ecstasy: it represents new trends in youth culture that have been taking place in dif-ferent countries in Europe over the past 10 years in some countries or more recently in others, and there is consider-able political and professional anxiety about these changes across and beyond Europe. Implicitly or explic-itly, qualitative studies of new drug trends and the drug use of young people are often designed to provide infor-mation for developing primary prevention or harm reduc-tion measures. In Ireland, for example, research activity has increased dramatically recently, as drug prevalence data suggest that in many respects Ireland now has a profile similar to that of the UK.

Injecting Risk Behaviour

Secondly, since the mid to late 1980s, concerns about HIV infection among injecting drug users have prompted a number of qualitative studies which have been designed to illuminate the detail of how drug users engage in behaviour associated with the acquisition of blood-borne vi-ruses. Increasingly, this work has widened its focus to include behaviour associated with other health risks such as hepatitis (HBV and HCV) and drug overdose. Such behaviours have represented a serious challenge to quali-tative methodology: the populations involved are often highly marginalised, and this results in ethical, practical and methodological problems for the researcher seeking to access them.

The Drug Use — Crime Relationship

The third area of policy-makers' concern which has prompted qualitative inquiry on the topic of drug consumption is the relationship between drugs and criminal activity. That is, drugs and crime at the local level: the point at which citizens and local inhabitants come face to face with drug users, the consequence of that in terms of crime and the problems this causes in terms of tensions within the community and, for local authorities, in terms of conflicts between police strategies and public health strategies. The concern over this aspect of drug use can be seen as stemming from a growing realisation among many EU countries of the high social cost associated with drug use. In some countries, qualitative studies have exploited the knowledge base that exists in departments of criminology and anthropology. In those countries which have not traditionally conducted qualitative studies of drug use (perhaps related to overall low levels of drug consump-tion), a tradition of conducting qualitative research has nevertheless existed in mainstream criminology or an-thropology university departments. Increasingly, these re-searchers have taken an interest in drug use issues, partic-ularly in relation to understanding patterns of offending.

Increasing the Impact of Qualitative Research on the Policy Agenda

One of the problems faced by researchers, regardless of their methodological orientation, is how to make their research relevant to, and impact on, the policy agenda. The future development of the project 'Co-ordination of working groups of qualitative researchers to analyse drug use patterns and the implication for public health strate-gies and prevention' will focus on supporting research development that is both methodologically rigorous and relevant to the needs of policy-makers. Traditional meth-odologies, such as school and household surveys, are not usually very adequate to trace new drug trends. Often, trends evolve among specific groups, which are not — or not sufficiently — represented among samples drawn from general populations. Moreover, specific questions on new drugs (or new ways to use drugs) can only be included in questionnaires used for such surveys if prior information is available.

Research can only be of use to policy-makers if it addresses those questions that are driving policy forma-tion in a timely fashion. Historically, qualitative research has often been characterised by intensive, long-term and detailed studies of specific subcultural groups. Often bor-rowing from anthropological methodological tradition, researchers have made considerable efforts to gain access and integration into the chosen study population. Whilst researchers conducting such work must be commended for their dedication, the time-consuming nature of this kind of enterprise is not always compatible with the demands of today's health care agenda. Qualitative re-search has the potential to develop the necessary rapid reporting systems demanded by policy-makers: today's public health agendas require the quick accumulation of knowledge on specific topic areas, and qualitative re-searchers have had to develop methods which allow focused data to be collected rapidly. This has led to some fruitful collaborations between qualitative and quantita-tive researchers, who have employed a mixture of their methods to produce some innovative studies of drug prev-alence, such as capture-recapture, network sampling, site sampling, snowball sampling and benchmark calculation techniques.

Qualitative research is also only likely to be influential if it has credibility with policy-makers. In some respects, the situation has recently improved, and there is evidence to suggest that policy-makers have become more sophisticated in their understanding of the importance of differ-ent types of data in developing an understanding of com-plex issues. However, much remains to be done, and in some EU countries it appears that the funding and sup-port of any research activity remains a low priority. This may be a particular problem for drug epidemiology, as scientific explanations and accounts do not always tally with the political agenda of policy-makers. If a broad view of drug-related policies is taken, accepting that 'policy' includes the local as well as the national level and em-braces changing the policies of particular agencies (for example, the police, the health services, the local govern-ment) or partnerships, then qualitative research can have a major impact on policy-makers' decisions. There are numerous situations where researchers are best able to enter and explore an aspect of drug use using qualitative methods (such as dealing), yet very often it is a high-pro-file politicised 'problem' they are funded to investigate, and, as such, the research results will affect policy and intervention. Because drug policy is entwined in moral and political debate, the media have a major role in influencing policy. Radio and TV programmes feed off qualitative 'stories' and illustrations of drug misuse, and, in response, policy and practice often change unofficially without political announcement. For example, in the UK, harm reduction strategies for drug users in clubs were incorporated into a radio documentary based on research into their activities.

Regardless of their methodology, studies are likely to be most influential if they are available in the public domain. The scientific scrutiny that such material re-ceives also helps to maintain quality. Thus, if qualitative research studies are not seen as methodologically rigor-ous, they are unlikely to be credible or influential. Evi-dence collected during the course of the project suggests that considerable difficulty is often experienced by qualitative researchers to get their work published in drug-spe-cific scientific journals. This appears to be due partly to the reluctance of some journals to accept qualitative work, but also because the qualitative papers are often longer and more discursive than most papers reporting on quan-titative studies. In the general social science field this is not a problem, as many specialist journals welcome such contributions. Although many drug journals have recently appeared more ready to consider qualitative reports than they did previously, a forum dedicated to publishing such material is overdue.

The project has demonstrated how much high-quality qualitative research is available across the EU. Many of the studies cited are available only in report form or in national publications, however. To date they have there-fore been unavailable to a wider, international audience. It is hoped that the project report will provide a useful resource to those who wish to learn more about the range of qualitative studies and their conclusions which have been conducted across the EU. The continuing support of the EMCDDA provides an opportunity for qualitative research to reach a wider audience including those design-ing policy, prevention or legislative inventions aimed at reducing the problems associated with drug consumption.

Country Profiles: Summaries

A summary of the profiles for each country follows: the full version can be found in the project report [1].

Austria

There are in Austria sociologists and psychologists who are interested and trained in qualitative research method-ology, and some of them use a mixture of qualitative and quantitative research methods in their work. Research on addiction is carried out at most universities in different departments, and there are two organisations which spe-cialise in the subject. However, there are few qualitative researchers working in the drug use area, and relevant studies and publications in the last decade are corre-spondingly rare. Just one study with a qualitative element is currently under way, funded by various government departments.

Belgium

Whilst there is qualitative research activity on drug use in the country, funded from a variety of sources, the results are not widely disseminated.

Denmark

Qualitative research projects on drug use in Denmark may be categorised as follows: (1) evaluation projects car-ried out by academics with no research/evaluation experi-ence; none of the research results/projects have been pub-lished in international/recog,nised journals but are avail-able as reports; (2) research projects carried out by quali-fied researchers with no or limited connection to universi-ties or research centres; (3) research projects carried out by qualified researchers employed by universities or re-search centres. However, little of this research is pub-lished, particularly outside Denmark. Current qualitative research into drug use is funded mainly by ministerial or university departments of social affairs/services.

Finland

In Finland, the drug field has attracted an increasing number of researchers in recent years, and the scope of sub-ject matters has widened considerably, assisted by initia-tives fostering international co-operation. A working relationship between policy-makers and the researchers work-ing in the drug field has been established: policy-makers have commissioned data collection and appointed re-searchers to working groups and committees. Nevertheless, drugs do not yet have an established position in the field of research, there are neither permanent drug research posts nor assured funding for projects. The priorities in funding have been a high scientific standard and the significance in estimating the overall drug situation, that is quantitative studies. In such a situation, it is unsurprising that few qual-itative studies have been conducted, although some re-searchers have incorporated some qualitative methods into their studies in the past few years. Only one current project with a qualitative element has been identified.

France

A profile for France is not available. It is hoped to add this to the updated version of the project report.

Germany

Although quantitative approaches still dominate re-search into drug use in Germany, qualitative methods have increasingly been employed over the last decade to investigate the problematic developments of HIV trans-mission and other risks, the limitations of the German treatment system (i.e. the abstinence model) and new drug trends amongst young people — although the drug-crime relationship has been largely ignored. Qualitative research is not widely disseminated outside the country, however.

Thus, whilst drug research in Germany is conducted largely from medical, psychiatric and/or neurobiological perspectives, social science approaches are playing an increasingly significant role. This has not only widened the themes studied, but has also provided opportunities for the development of qualitative methods. The changes of type of research reflect a corresponding move in some states away from the abstinence model of treatment towards a harm reduction policy.

Greece

No evidence of qualitative research or researchers was located for Greece. This lack could be attributed to a com-bination of factors related to limited funding, priorities focusing mainly on epidemiological research and lack of a solid background and training of professionals in qualita-tive research.

Ireland

In Ireland to date, few research studies (either quanti-tative or qualitative) have been undertaken on the use of illicit drugs, despite indicators of a concentration of heroin use in the marginalised areas of Dublin city and a growing normalisation of cannabis and ecstasy use among young people throughout the country. However, a number of drug research studies have recently been funded by a new government initiative, including some using qualita-tive methodologies.

Italy

Research on aspects of drug use in Italy is largely of a quantitative nature, with the focus on accounts of policy, history, politics and legal issues, conducted from an epi-demiology or psychology point of view. There are few exceptions to this general pattern, and little current quali-tative activity was located.

Luxembourg

Investigations into qualitative research in Luxembourg have revealed little relevant activity, although some re-searchers into drug use incorporate qualitative techniques into their work. However, there are no records of qualita-tive research conducted in Luxembourg being published in any form over the last decade, or of any current projects containing a substantial qualitative element.

Netherlands

Qualitative research on drug use began in the 1980s in the Netherlands, and is characterised by typology studies based on autobiographical interviews. Most have focused on either dependent drug users, polydrug users or 'recreational' drug use. The drug-crime relationship has been the topic of many qualitative studies, as have the drug-using patterns of, particularly, cocaine and ecstasy users. Rarely have female and ethnic minorities been the focus of this research, however. The Netherlands have a rela-tively low prevalence of HIV and AIDS among injecting drug users (of which there are relatively few), and few qualitative studies of injecting risk behaviour have been conducted.

Funding for qualitative research is currently provided by a diverse range of agencies, but from 1998 to 2002 changes in funding sources may affect the focus of future studies.

Portugal

It has been possible to trace only one qualitative researcher and his work for the country.

Spain

Until the late 1980s in Spain, research into drug use was mainly epidemically orientated, and little attention was paid to qualitative methods. Research and interven-tion in Spain have become increasingly institutionalised and were developed — and remain — orientated towards heroin. In addition, studies have concentrated on epide-miology rather than processes, motives and causes, and have been dominated by health specialists and quantita-tive sociologists and psychologists. The result is that, until the 1990s, qualitative research was restricted to comple-menting surveys and questionnaires with discussion groups, and there appeared to be a lack of interest and funding in the explanation of a phenomenon.

However, the drug-related spread of HIV has stimulat-ed a more qualitative approach to research into aspects of drug use, and this has led to the development of more diverse and rigorous qualitative methodologies. This re-flects the awareness that, given the dramatic changes in drug-related problems in the last decade, there is a need to integrate, debate and learn from different research ap-proaches and backgrounds.

Sweden

The data collected on qualitative researchers into drug use in Sweden show that all are employed at universities, in sociology, criminology or social work departments. The themes of the published work reflect this, although it has not been widely disseminated.

United Kingdom

Since the 1960s, qualitative research has played a key role in describing the social relations and context of illicit drug use and drug-using life-styles, and multi-method research approaches have long been a feature of UK drug research. In the last decade (1987-1997), advocates of qualitative research in the UK have not only emphasised the methodological desirability of using qualitative meth-ods for researching hidden or hard-to-reach populations, but have also emphasised the practical utility of qualita-tive data. With the advent of HIV infection and AIDS, qualitative methods have proved invaluable for describ-ing and understanding the social context of risk associated with injecting drug use, and in assisting with the develop-ment of health promotion and prevention interventions. The increased receptivity of governmental funding agen-cies, such as the Department of Health and Home Office, to sponsoring qualitative drug research was largely born out of public health concern to inform HIV prevention and reduce HIV transmission. The impact of HIV infec-tion and AIDS on the direction and parameters of the UK drug research agenda, and of qualitative research in par-ticular, cannot be underestimated.

In the last 10 years, the key areas of investigation of UK qualitative drug research have largely been in-fluenced by public health concerns, and HIV infection and AIDS in particular. The focus of almost all qualitative research has been on the drug user, and in elucidating drug user perspectives on the social meanings and context of drug use and associated health behaviours. There is comparatively little qualitative research focusing on health providers or drug treatment processes, although ethnographies have been undertaken on methadone pre-scribing and qualitative methods have been used in a vari-ety of process evaluations.

The future of qualitative drug research in the UK remains uncertain given changing funding priorities and the narrowing funding base for HIV/AIDS research. There remains a continued receptivity to the use of quali-tative methods in drug research, but positivist, deductive and quantitative paradigms clearly remain dominant.

Accessing Hidden Publications:

The Search for Research and Researchers

A description of the methods used to conduct the search for qualitative publications, current projects and researchers is presented in this section. Methods used to collect information included computerised database searches, a manual review of journals, Internet searches and networking with qualitative researchers from each EU member country. These methods were used simulta-neously, in order to maximise the chances of producing the most comprehensive audit possible within the given time frame of the project. To explore the extent to which qualitative studies are published in specialist drug jour-nals, the output from three journals was audited for 1 year. The data suggest that qualitative studies represent a very small percentage of the total output of drug-based scientific publishing, although firm conclusions cannot be drawn from such a partial exercise.

Searches of Computerised Databases

The search for relevant publications began with searches of three computerised databases: Medline, Psy-clit and BIDS. It proved largely unproductive. For exam-ple, a search on all three databases using the key words 'qualitative methods' and 'drug abuse' provided under 10 citations for each. This is mainly because qualitative methods are not routinely mentioned in journal abstracts, nor as key words. Further, a large proportion of the tar-geted research is published in the form of books, book chapters and as 'grey' literature (reports which have not been formally published but submitted to the agency which commissioned the research) which are often not included in electronic databases or citation indexes. Searches of national databases throughout the EU en-countered the same problems. One of the added value components of this project is that a database of qualita-tive research on drug use in the EU now exists and will be available via the Internet in 1998.

To increase the 'hit' rate, databases were searched without reference to qualitative methodology, by, for example, searching under a known qualitative researcher's name or under an area of research such as 'HIV and risk'. Whilst this strategy proved more successful in locating published research, the grey literature remained largely elusive.

Manual Review of Journals

Key international journals were selected for a manual review. In order to maximise the chances of finding relevant papers, journals covering a wide range of disciplines were examined. These included: drug use, AIDS, sociolo-gy, psychology, medicine and criminology. Reference lists in publications were also scrutinised to generate further names and texts.

The Internet

The Internet proved an effective search tool. The facility was used to access, for example, library catalogues, dis-cussion groups, university departments, electronic journals, publishers, research institutions and governments.

Networking

Reaching an Internet site such as those listed above does not, of course, lead to a ready-made list of qualitative research and researchers. However, these sites do yield links which can be exploited, and these frequently lead to success. For example, lists of departmental staff at a uni-versity sometimes give their research interests. If these included drug use or qualitative methodology, they were contacted, and a snowballing process began, leading to other individuals and institutions. The search team also joined drug use research e-mail databases and advertised for contributions from other members.

In order to achieve the project's aims, existing EU-wide contacts were utilised and new relationships estab-lished: a key group of qualitative experts in the field of drug use was recruited from each of the 15 member countries, and contact was made with relevant institutions such as university departments, libraries, Reitox Focal Points and drug treatment agencies. Snowballing from these liaisons led to other individuals and institutions, and a seminar of specially invited qualitative researchers was held. Networking was an essential component of the search for published and grey literature, researchers and current projects. This was particularly the case for access-ing grey literature, much of which is not widely circulated.

The result of the simultaneous use of the search pro-cesses detailed above is a comprehensive and accurate bibliography, directory of qualitative researchers, and inventory of current projects, all of which were validated via these contacts throughout their compilation. This report can therefore claim to be a credible account of the diversity and richness of qualitative research across the EU. It provides the first EU-wide database of qualitative researchers, their current work, and their output over the last 10 years and is now available on the Internet (www.qed.org.uk). Over the next year, a website dedi-cated to qualitative research on drug use will be established as part of the EMCDDA's continuing commitment to support networking activities in this area.

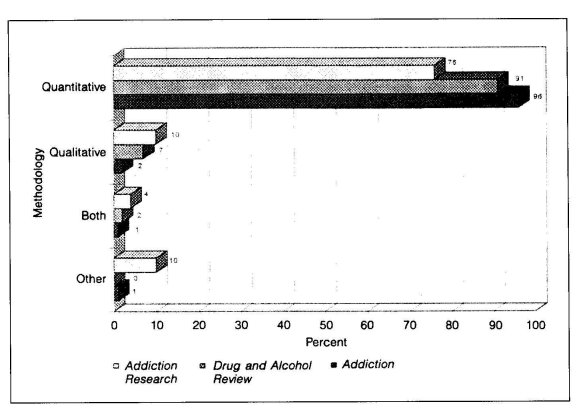

Survey of Three International Journals

To give an indication of the amount of qualitative research published in drug use journals, a content analysis was conducted on 291 papers from three leading international publications in the year 1995-1996: Addiction, Drug and Alcohol Review and Addiction Research. Addic-tion covers a broad area of drug, alcohol and nicotine studies with occasional papers on other compulsive be-haviours, such as gambling. It is published 12 times per year. Drug and Alcohol Review looks at clinical, biomedi-cal, psychological and sociological aspects of alcohol, tobacco and drug use and is published 4 times yearly. Addiction Research examines the effects of context on the use of all substances. It published work which is primarily psychological and sociological in origin, 4 times a year.

The survey was designed to discover: the proportion of papers using qualitative methodologies in relation to the total published; the differences among journals in relation to the proportion of qualitative papers published; the proportion of qualitative papers published by EU researchers in relation to those submitted from elsewhere. A total of 291 papers were examined. Seventeen (6%) reported on studies which had used qualitative methods, wholly or in part.

Fig. 1. Proportion of qualitative papers pub-lished in three international journals during 1995-1996.

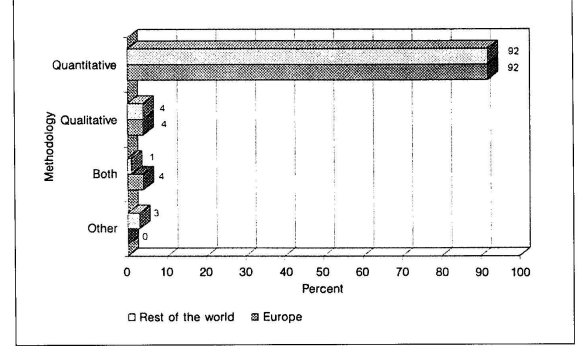

Fig. 2. Methodology of papers published in three international journals during 1995- 1996: comparison between the EU and the rest of the world.

Results

The largest number of qualitative papers published over the survey period was found in Addiction Research. As shown by figure 1, 10% of articles published in this journal were of studies using qualitative methods, and a further 4% had used a combination of both quantitative and qualitative methods. A smaller proportion of qualita-tive articles were found in Drug and Alcohol Review (7°/0) and Addiction (2%).

Figure 2 shows that there was no difference between the proportion of papers published by EU qualitative researchers and those published by qualitative researchers from the rest of the world (4%). However, EU researchers had published a higher proportion of articles which used a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods (4°/o: 1%).

A larger study would be needed before any definite conclusions can be drawn from this example, where only three journals were surveyed. For example, it is not known how many qualitative papers were submitted to, and rejected by, the journals. However, the findings indicate that although qualitative research is not published with the same frequency as that using quantitative meth-ods, EU researchers publish more in comparison with those from the rest of the world.

The Seminar

A seminar 'Qualitative research: method, practice and policy' was held in Bologna, Italy, on July 2-4, 1997, hosted by the Region of Emilia-Romagna and organised for the EMCDDA by the NAC (UK) and the European Forum for Urban Security. Participants were chosen to include those who were well informed on the relevant issues at local, European and global levels, from both a practical and theoretical viewpoint, and the first draft of this report was distributed to them for discussion. Their contributions to both the design and output were an essential element of the project.

During the seminar, more than 60 researchers focused on how qualitative research can contribute to epidemio-logical understanding of the drug phenomenon by de-scribing and interpreting the processes underlying the statistics, and how these insights can help formulate relevant responses. It was clear that a substantial body of qualita-tive research and expertise exists in a few countries, whilst, in others, this is a novel approach. It was also clear that there is untapped potential for bringing this knowl-edge into the policy domain.

Presentations and discussions at the seminar covered the following topics:

— a historical perspective on qualitative research;

— some initial results from the literature search for quali-tative publications;

— reviews of qualitative research in several EU member countries;

— case studies: crime and drug use/drug markets; drug rationing and help-seeking among heroin users; con-text, risk and intravenous drug use;

— qualitative research impacting on the policy agenda; qualitative research and the policy agenda; the use of qualitative data: the political point of view; the role of qualitative research in affecting drug policies;

— methodology: the interactions between qualitative and quantitative research; rapid reporting systems; innova-tive methodology to assess new drug trends;

— workshops: three workshops were held, where ideas were exchanged on methods, the results of studies, and future collaborative projects; the themes of the work-shops were new trends in drug use, injecting risk behaviour and the relationship between drug use and crime.

Feedback and Follow-Up

A major aim of the seminar was to use it as a resource, and the feedback from the participants has shown that it was considered to be a very successful event from a number of points of view. It enabled the NAC staff working on the project to consolidate working relationships with a network of qualitative researchers throughout the EU and to establish new ones. These relationships were invaluable in achieving the aims of the project. Regular contact has been maintained with the network, leading to the estab-lishment of a structure which has not only assisted the validation process of the contents of this report but also forms the basis of future collaborative projects. Both in Bologna and in the months following, the comments and recommendations emanating from this network have been incorporated into the planning and execution of the project. It is envisaged that the formation of this well-informed network of qualitative researchers will raise the profile of qualitative research in the EU.

References

1 Fountain J, Griffiths P (eds): EMCDDA: In-ventory, Bibliography and Synthesis of Quali-tative Research in the European Union. Lon-don, Lisbon, NAC/EMCDDA, 1997.

2 Denzin NK, Lincoln YS: Handbook of Quali-tative Research. Thousand Oaks, Sage, 1994.

3 Lambert EY, Ashery RS, Needle RH: Qualita-tive Methods in Drug Abuse and HIV Re-search. NIDA Research Monograph 157. Rockville, NIDA, 1995.

4 Silverman D: Qualitative Methodology and So-ciology. Aldershot, Gower, 1985.

5 Rhodes T, Cusick L: Profile of qualitative re-search in the UK; in Fountain J, Griffiths P (eds): EMCDDA: Inventory, Bibliography and Synthesis of Qualitative Research in the Euro-pean Union. London, Lisbon, NAC/EMCD-DA, 1997, vol 1, section 2.

6 Gamella JF, Romo N, Roldan AA: Profile of qualitative research in Spain; in Fountain J, Griffiths P (eds): EMCDDA: Inventory, Bibli-ography and Synthesis of Qualitative Research in the European Union. London, Lisbon, NAC/ EMCDDA, 1997, vol 1, section 2.

Last Updated (Friday, 18 February 2011 13:05)