| Articles - Various research |

Drug Abuse

DRUG AND ALCOHOL USE AND THE LINK WITH HOMELESSNESS:

RESULTS FROM A SURVEY OF HOMELESS PEOPLE IN LONDON

JANE FOUNTAIN a'*, SAMANTHA HOWES b, JOHN MARSDEN b, COLIN TAYLOR b and JOHN STRANG b

'Centre for Ethnicity and Health, University of Central Lancashire, C/o DrugScope, 32-36 Loman Street, London SEI OEE, UK; bNational Addiction Centre, Institute of Psychiatry/Maudsley Hospital, 4 Windsor Walk, London SE5 8AF, UK

Addiction Research and Theory August 2003, Vol. 11, No. 4, pp. 245-256

A community survey using a structured questionnaire was used with 389 homeless' people currently or recently sleeping rough (on the streets) in London. Data were collected on respondents' histories of homelessness and of substance use, and dependence on the main substance used in the last month was measured. In the month before the interview, 83% (324) of the sample had used a drug, 36% (139) were dependent on heroin and 25% (97) on alcohol. Sixty-three per cent (244) reported that their drug or alcohol use was one of the reasons they first became homeless, but the majority (80%, 310) had used at least one additional drug since then. Overall, drug and alcohol use, injecting, daily use and dependency increased the longer the respondents had been homeless. A clear link exists between substance use and homelessness: initiatives to tackle homelessness must simultaneously tackle the drug use of homeless people.

Keywords: Homelessness; Rough sleeping; Drugs; Alcohol; Homelessness and substance use

INTRODUCTION

A high level of drug and alcohol use amongst various sections of the homeless population has been reported worldwide, including the USA (e.g. Wright and Weber, 1987; Nyamathi et al., 1999), Australia (e.g. Downing-Orr, 1996), across the European Union (e.g. Avramov, 1988), and in the UK (e.g. Farrell et al., 1988; Fitzpatrick et al., 2000). In the UK, a special `homelessness czar' and a Rough Sleepers Unit (RSU) have been established, but there has been little dedicated research on the substance (i.e., drugs and alcohol) use of homeless people. Thus, policies dealing with homeless people who use drugs and alcohol may be based upon extremely crude estimates of the prevalence of this behaviour. To address the gaps in knowledge, a dedicated survey of substance use amongst people currently or recently sleeping rough (on the streets) in London was organized. A major aim of the survey was to explore the relationship between homelessness and substance use, and this paper presents some results from the project.

It is not possible to provide an accurate number for homeless people in the UK, due to the reliance on estimates, differences in the definition of `homeless', and the unknown numbers who are `hidden' from official statistics such as, for example, those applying to local authorities for social housing (Fitzpatrick et al., 2000). In London alone, however, over 450 hostels provide around 19,600 beds for `single homeless people' (DTLR, 2001). There have also been attempts, through street counts, to ascertain the numbers sleeping rough. The RSU estimated that, in June 2000, 1180 people slept rough on the streets of England on any one night — 535 of them in London (RSU, 2000). The RSU has a target of reducing these numbers `to as near zero as possible, and by at least two-thirds, by 2002' (DETR, 1999: 7). This population is not stable, however: the numbers sleeping rough annually have been estimated to be up to six times than on any one night (Social Exclusion Unit, 1988), and some individuals move through repeat cycles of rough sleeping to various forms of temporary and emergency accommodation.

In the UK, the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD) report that the substance use of those using services for homeless people is `considerably beyond that occurring in the general population' (p. 89), with 8% of those sleeping rough and using day centres dependent on a drug (excluding cannabis) and 36% dependent on alcohol (ACMD, 1998). More recently, the proportion of those sleeping rough who use drugs has been estimated to be 20% (Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions/DETR, 1999 : 8) and the proportion who are alcohol dependent at 50% (DETR, 1999 : 8). The RSU is working with the UK Anti-Drugs Co-ordination Unit (ADCU — now renamed the Drugs Strategy Directorate) (Tackling Drugs to Build a Better Britain, 1998) to provide strategic oversight to local initiatives to help those sleeping rough who have drug-related problems. However, as evidenced by, for example, the cursory references to problem substance use in the Social Exclusion Unit's report to parliament on the strategy to reduce the numbers sleeping rough (Social Exclusion Unit, 1998), there are gaps in the knowledge which would provide a detailed understanding of the relationship between these issues. For example, little is known about the patterns of substance use by those sleeping rough in the UK. The only questions on drug and alcohol use on the questionnaire administered to all cold weather shelter users (who were sleeping rough prior to entering these shelters) are boxes marked `drugs advice' and `alcohol advice' to record self-identified needs on arrival, producing positive results of 22% and 20% respectively (CRASH, 2000). The substance use needs of those sleeping rough recorded by outreach teams (HSA, 1999) also lack detail. They are dependent on self-report and/or an on-the-spot needs assessment by an outreach worker, and are recorded only as 30% for drugs and 38% for alcohol.

METHODS

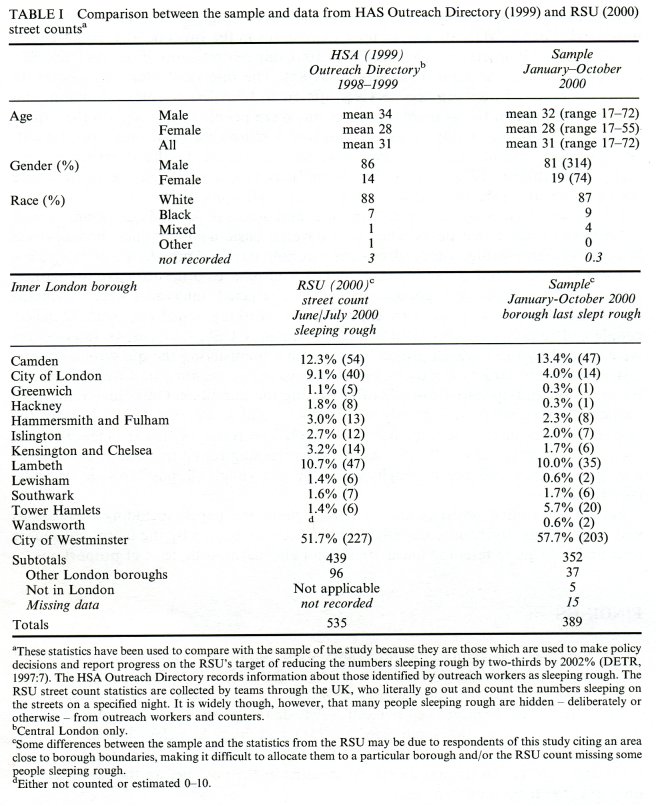

Interviews were conducted from January to October, 2000, with a convenience sample of respondents who had slept rough for at least six nights in the previous six months. The period of six months was chosen so as to capture those who had spent several months in a cold weather shelter, but who were sleeping rough prior to that period (and in many cases were likely to be returning to sleeping rough after it). Interviews were carried out in 20 locations and took place in (or in the street nearby) cold weather shelters (28%/110 interviews), hostels (27%/106), day centres/drop-in centres (23%/88), and `rolling' (i.e., temporary) shelters (22%/85). The interview sites were chosen to cover the range of homelessness services offered to homeless people in London, and to attempt to match the available statistics on where people sleep rough in the capital (Table I). Health and safety considerations and a reluctance to disrupt work by outreach workers meant that interviews were not conducted on the street during the night. Nevertheless, 17% (67) of the respondents had slept rough the night before the interview and 16% (61) expected to do so the following night.

Interviews lasted between 25 and 45 minutes and used a structured questionnaire with some linked open-ended items. Questions covered basic demographics; homelessness history; substance-using history (drugs and alcohol); past and present use of drug, alcohol and homeless services; and income and expenditure. In order to maximise participation by the marginalized population that was targeted, interviews were conducted by 10 members of a team with experience of working sensitively with homeless people and respondents were paid £10 (approximately US$14, 16 euros). Interviewers were trained by the research project manager in administering the questionnaire, and instructed not to target drug users, but to interview any person who fitted the criteria for inclusion and appeared capable of answering the questions. Only three refusals to participate were reported and only one interview had to be abandoned, because the respondent was under the influence of alcohol. The result of this strategy was that the sample was typical of all those recorded as sleeping rough in London in terms of age, gender, race and the borough where the last rough sleeping episode occurred (see Table I).

Simple descriptive statistics are used throughout the paper, including correlations and proportions. Relevant comparisons have been supported by the use of chi-square tests and chi-square tests for linear trend, and also asymptotic tests of proportions.

FINDINGS

Three hundred and eighty-nine interviews were conducted. Respondents comprised 81% males and 19% females, with an average age of 31.10 (range 17-72). One-third (33%, 129) were aged 25 and under, 74% (286) aged 35 and under, and 5% (18) aged 50 and over. Eighty-seven per cent (324) described their ethnic group as white. Almost two-thirds of the sample (62%, 241) had been homeless for six years or longer, and less than a fifth (18%, 70) for two years or less. Forty-eight per cent (187) had slept rough for more than six months in the year before the interview and only 8% (29) for a month or less.

The Substance Use of the Sample

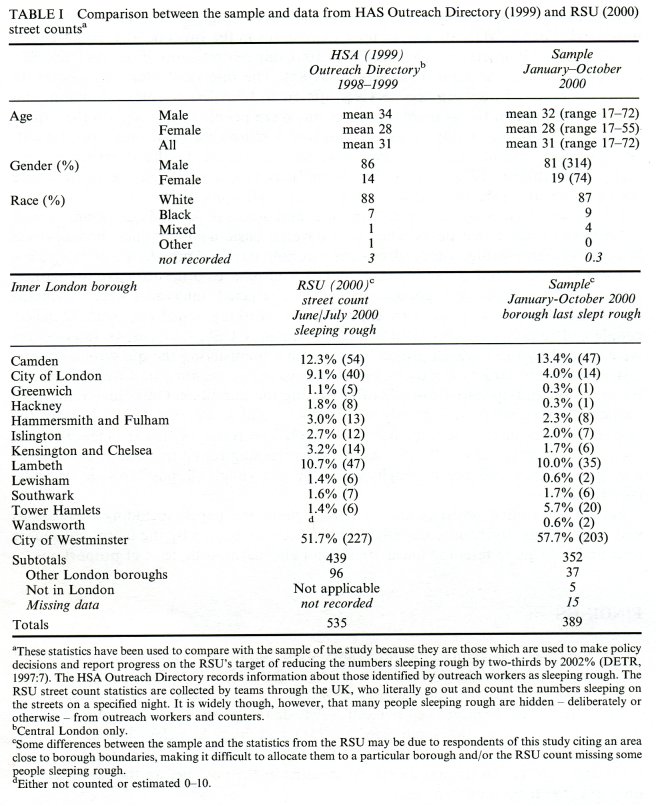

Table II shows the substance use of sample over three time intervals – ever, in the last year and in the last month. Although substance users were not targeted for the study, in the last month, 324 (83%) had used a drug (excluding alcohol), only 4% (17) had used neither any drug nor alcohol, and 12% (48) had used alcohol only. In the last month, around two-thirds had used cannabis and alcohol, almost half had used heroin and/or crack cocaine; and around a third had used benzodiazepines and the same proportion had used opiates other than heroin. The use of stimulants other than crack cocaine was lower, although a quarter of the sample had used cocaine powder, amphetamine and/or ecstasy. Far fewer had used an hallucinogen or solvents.

Polydrug use was common On average, drug-using respondents had each used three to four drugs in the last month. Over a third of the sample (38%, 146 of 389) had used both heroin and crack in the last month, with half of these (73, 19% of the total sample) using both drugs on 25 or more days. The use of crack cocaine frequently accompanied the use of heroin, with 80% (146 of 182) of those using crack cocaine in the last month having also used heroin. The use of benzodiazepines in combination with heroin and crack cocaine was also common. Over half of the 146 respondents using both heroin and crack cocaine in the last month had also used benzodiazepines (54%, 79), and 58% (85) had also used alcohol, of whom a third (33%, 28 of 85) were drinking daily.

Those who had used a drug in the last month were asked from where they usually obtained it. Almost all illicit drugs were bought on the illicit market — those that were not had been given to the respondent by friends. In the case of drugs prescribed to substance users in treatment (for example, methadone and benzodiazepines), more of those who had used these substances in the last month had bought them on the illicit market than had a prescription for them. For example, of the 111 respondents who had used diazepam, almost three-quarters (72%, 79) usually bought it on the illicit market, whereas only 19% (21) had their own prescription for the drug (z = 7.07, p < 0.0001). Overall, 32% (125) of the sample had used at least one type of benzodiazepine in the last month, of whom 75% (94) had used at least one bought on the illicit market.

Respondents were asked on how many days in the last month they had used each of the substances they used. Results in Table II show that 70% (129) of the 184 `last month' heroin users used the drug on 25 days or more during the preceding month; 53% (140) of the 264 alcohol users; 46% (84) of the 182 crack cocaine users; and 41% (103) of the 253 cannabis users.

In the month prior to the interview, 157 respondents (40% of the whole sample) had injected a drug — almost half of all those who had used a drug (48%, 157 of 324) in this period. Over a third of the total sample (37%) had injected heroin and 18% (69) had injected crack cocaine.

Respondents were asked to name the main substance (including alcohol) they had used in the last month, or, if they did not use one substance more than others, the one that was causing them the most problems. A greater proportion of the heroin users (three-quarters of them — 76%, 139 of 184) than the users of any other substance cited it as the main one they used. Just under half (46%, 120) of the 264 who had used alcohol, 21% (21%, 38) of the 182 who had used crack cocaine, 18% (45 of 253) of the cannabis users, and 0.8% (1 of 125) of the benzodiazepine users reported these as their main substances.

Respondents were asked a series of questions to measure their dependence on the main substance they had used in the last month, using a checklist of symptoms derived from and compatible with both DSM-IV and ICD-10 (American Psychiatric Association, 1994, World Health Organisation, 1992). Eighty per cent (312) of respondents scored as dependent on the main substance (a drug or alcohol) they had used; 66% (215) were dependent on the main drug they had used; and 81% (97) of the 120 whose main substance was alcohol were dependent on it. Thirty-six per cent (139) of the whole sample scored as heroin dependent, 25% (97) as alcohol dependent, and 9% (34) as dependent on crack cocaine.

The Relationship between Substance Use and Homelessness

The data reported in the previous section have charted the extent of the substance use, injecting and dependence amongst the sample. In this section, data are provided on the relationship between substance use and homelessness, reporting the results from an examination of the nature of the relationship between an individual's substance use and becoming and remaining homeless, in terms of the length of time respondents reported being homeless; substance use of current peers; perceived reasons for becoming and remaining homeless; patterns of substance use since becoming homeless; substance use when sleeping rough; and changes in substance use in relation to changes in accommodation status.

Duration of Homelessness and Substance Use

The data on substance use were analysed in relation to the length of time respondents had been homeless. Overall, substance use, injecting, daily use and dependence increased over time. For example, the use of alcohol was most common amongst those who had been homeless for 10 years or more, of whom 76% (106) had used it in the last month, compared with 60% (42) of those who had been homeless for two years or less (x2= 5.75, df=1, p < 0.017); and whilst 57% (41) of those who had been homeless for two years or less had used a substance other than heroin, crack cocaine and alcohol in the last month, 88% (67) of those who had been homeless for three to five years had done so. However, the length of time respondents had been homeless was not as strongly related to the use of crack cocaine and heroin. In the last month, 43% (30) of the 70 who had been homeless for two years or less had used crack cocaine, as had 45% (34) of the 76 who had been homeless for 3-5 years, 52% (53) of the 102 who had been homeless for 6-10 years, and 47% (65) of the 139 who had been homeless for more than ten years. Of the 70 respondents who had been homeless for two years or less, 39% (27) had used heroin in the last month, whereas 49% (68) of the 139 who had been homeless for 10 years or more had done so.

The daily use of heroin and/or crack cocaine also increased with the length of time respondents had been homeless and was most common amongst those who had been homeless between three and ten years. Thirty per cent (21) of those who had been homeless for two years or less used heroin and/or crack cocaine daily; 40% (30) of those who had been homeless for three to five years; and 41% (43) of those who had been homeless for 6-10 years. The proportion decreased to 36% (50) of those who had been homeless for 10 years or longer.

Injecting, too, increased with the time respondents had been homeless. In the last month, just over a quarter (27%, 19) of those who had been homeless for two years or less had injected a drug, whereas almost half (46%, 111) of those who had been homeless for more than six years had done so (x2 = 8.09, df = 1, p < 0.005).

Forty-nine per cent (34) of those who had been homeless for two years or less scored as dependent on their main drug. The peak period of dependence was during the third to the fifth year of homelessness: 63% (48) of this group was dependent on their main drug. Dependence on alcohol increased with the length of time respondents had been homeless, from 19% (13) of those who had been homeless for two years or less to 32% (45) of those who had been homeless for more than ten years (x2= 3.88, df = 1, p < 0.05).

Social Contacts and Substances Use

Respondents were asked how many other homeless people they `hung around with' on a typical day, and about the substance use of these social contacts. Most spent their time with groups of other homeless people they considered to use the same amount of, or more, drugs and alcohol than the respondent did. On a typical day, 80% of respondents (311) spent time with other homeless people. Of these, approximately half (49%, 151) said that these people had similar levels of drug use to their own. A third spent time with people who they considered to use more drugs than they did (34%, 105). Only 7% (26) of respondents spent time with people who they believed used fewer drugs than they themselves did and another 7% (26) with non-drug users. A third of the sample (33%, 102) spent their time with others who had similar levels of alcohol use, whilst half (49%, 154) spent their time with other homeless people who used more alcohol than they did themselves. Those few respondents who had not used drugs nor alcohol in the last month (4%, 17) were less likely than drug and alcohol users to spend time with other homeless people (x2 = 16.77, df = 1, p < 0.0001): 41% of this group spent time with other homeless people, compared to 82% of the drug and/or alcohol users.

Causes of Homelessness: Respondents' Opinions

Respondents were given a list of reasons why people might become homeless and asked to rate how much each contributed to themselves first becoming homeless. The majority of those using drugs and/or alcohol prior to becoming homeless had multiple problems which they perceived as contributing towards them becoming homeless. Almost two-thirds of the sample (63%, 244) cited drug and/or alcohol use as a reason for becoming homeless, and just under half (47%, 183) reported this as a major reason. The respondents who cited drug and/or alcohol use as being a reason for becoming homeless also gave other reasons, reporting problems with parent(s) (58%, 142); partner (34%, 83); money (49%, 119); the police (44%, 108); and mental health (21%, 51). Twenty-six per cent (64) reported leaving prison as an additional reason. Since this first instance of homelessness, 52% (204) of the sample had been homeless more than once. These respondents were asked to give up to two reasons for this. Drug use was by far the most common (42%, 85). Alcohol use was given as reason by 18% (36).

Since first becoming homeless, 48% (185) of the sample had been continually homeless. These respondents were asked to give reasons for this and the two most commonly cited were drug use (29%, 54) and financial problems (29%, 54), with 12% (23) citing alcohol use.

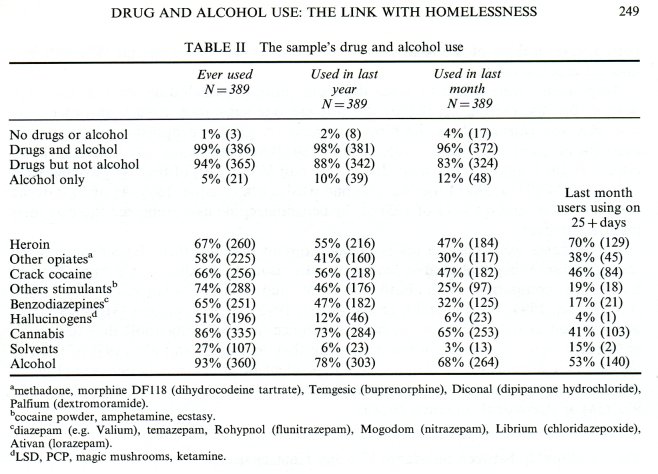

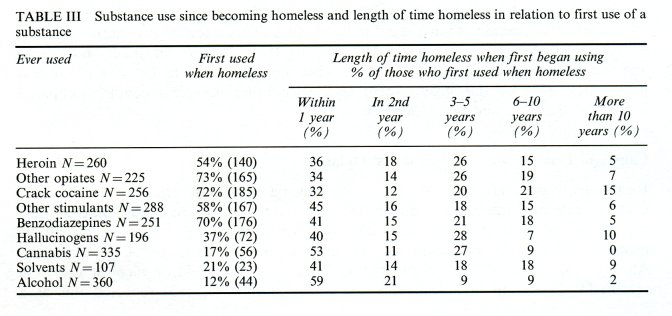

New Drug Use Post-Homelessness

Whilst 50% (193) of respondents believed that their drug use had contributed to them first becoming homeless, 80% (310) of them had started using at least one new drug whilst homeless. As can be seen from Table III, almost three-quarters (72%/185) of those who had ever used crack cocaine had done so after they became homeless, as had 58% (167) of those who had ever used other stimulants (cocaine powder, ecstasy and amphetamine), and 70% (176) of those who had ever used benzodiazepines. Almost half (46%/120) of those who had ever used heroin had done so before they became homeless, however, and the majority (83%/279) of those who had ever used cannabis had done so before they were homeless.

Respondents were asked where they were living when they first used each of the substances they had ever used Analysis of the data revealed that if they were homeless when they began to use a substance, they were most likely to have been sleeping rough (x2= 184.41, df = 1, p < 0.001). A small minority had begun to use a new substance whilst living in accommodation provided for homeless people (although not necessarily on the premises). For example, of the 140 respondents who began using heroin whilst they were homeless, almost two-thirds (62%, 87) had done so whilst sleeping rough.

Ten per cent (14) had first used heroin whilst living in a hostel; 4% (6) whilst in bed and breakfast accommodation; and 0.7% (1) in a cold weather shelter and the same proportion in a night shelter.

The data were also examined to establish how long after becoming homeless respondents had first used a substance. Results (Table III) show that in the case of every substance, the greatest proportion of respondents began to use it within one year of becoming homeless. For example, of those who had not used heroin until they became homeless, 36% (94) used it within one year, whereas only 5% (13) began using the drug after being homeless for more than 10 years; and 32% (82) of those who had not used crack cocaine until they became homeless did so in the first year. Nevertheless, every substance acquired new users over time.

Substance Use Whilst Sleeping Rough

When asked how often they had each substance during their last period of sleeping rough, equal proportions replied that they had always or almost always used heroin (41%, 158) and alcohol (41%, 160); 32% (126) that they had always used cannabis; and 27% (103) they had always used crack cocaine. Fewer respondents reported that they had always used methadone (10%, 40), benzodiazepines (6%, 22) and stimulants other than crack cocaine (5%, 19).

Drug and Alcohol Use in the Last Year and Next Year

Respondents were asked if their drug use had increased, decreased or stayed the same in the last year. Thirty-six per cent (139) reported that their drug use had increased; 22% (85) that it had decreased; and 42% (165) that there had been no change. Changes in drug use were correlated with changes in accommodation situation (r = 0.1627 [x2 linear trend] p < 0.001): an increase in drug use was correlated with a worsening accommodation situation.

Respondents were asked the same question about their alcohol use. Twenty-eight per cent (109) reported that their alcohol use had increased in the year; 23% (89) that it had decreased; and 49% (191) that there had been no change. Perceived changed in alcohol use were also correlated with changes in accommodation situation (r = 0.102 [x2 linear trend] p< 0.05): as with drug use, an increase in alcohol use was correlated with a worsening accommodation situation.

Respondents' perceptions of their drug and alcohol use in the next year were modestly correlated with how likely they though they would be sleeping rough. There was a tendency for those who predicted an increase in drug or in alcohol use to believe that they would also be sleeping rough (drug use r= 0.33 p< 0.001 /alcohol use r = 0.23 p< 0.001).

DISCUSSION

Homelessness and substance use represented two of today's most pressing social concerns. Both are strongly associated with social exclusion and often coalesce with a range of other social and individual problems. The existing research literature in this area suggests that simple causal explanations of the relationship between homelessness and substance use are inadequate: whilst the risk factors for homelessness and for health problems (including problematic substance use) are similar, cause and effect have proved difficult to disentangle (e.g. Bines 1994; Hutson and Liddiard, 1994; Ducq et al., 1997; Johnson et al., 1997; Neale, in press). However, if interventions are not informed by better understanding of the relationship of these phenomena, they may be ineffective, or even counter-productive.

The RSU/UKADCU partnership to tackle drug use amongst homeless people is timely: this report has revealed close links between homelessness and major drug and alcohol problems amongst homeless people in London. However, the results also suggest that the government's strategy on rough sleeping may have seriously underestimated the proportion of those sleeping rough who have drug problems. The service response has been devised based on an assumption of only 20% of those sleeping rough were drug users (DETR, 1999:8). As the sample of this study was typical of all those sleeping rough in Inner London, it is likely that this assumption is at least a threefold underestimate. The discrepancy between the government statistics on the drug use of homeless people and the data from this study is likely to be for a number of reasons: a comprehensive prevalence survey had not been conducted before the strategy was devised and hence data which have previously been available on the number of drug users amongst those who access services for homeless people may not reflect the whole population; and a large proportion of drug use by homeless people is hidden from service providers (and therefore their databases) because the exclusion of drug users from much temporary and emergency accommodation leads to its deliberate concealment.

The pharmaceutical drugs used by the sample were only rarely obtained legitimately on prescription and were more typically bought on the illicit market, especially in the case of benzodiazepines. In addition, almost three-quarters had not used pharmaceutical opiates nor benzodiazepines until after they had become homeless. There is little UK research on the diversion to the illicit market of drugs prescribed to those dependent on drugs or alcohol, and this study did not specifically explore this issue, but Fountain et al. (2000) have separately found that those using illicitly obtained prescription drugs are unlikely to be engaged in self-treatment. Rather, these drugs are part of polydrug-using repertoires. The source of drugs prescribed to substance users in treatment which are diverted to homeless people now needs to be investigated, although any ensuing action needs to balance diversion control against deterring drug users from accessing treatment.

More of the sample of this study were dependent on heroin than on alcohol. Whilst the government may have underestimated the proportion of those sleeping rough who use drugs, they may have, on the basis of our findings, been more accurate in the assumption of the proportion dependent on alcohol. In this study, of those who said alcohol was the main substance they had used in the last month, 37% scored as dependent on it compared with the assumption of 50% in the government strategy (DETR, 1999 : 8). However, as this study measured dependence only on the main substance reported to have been used in the month before the interview, it is probable that some respondents who cited a drug as their main substance were also dependent on alcohol. If resources for services for homeless substance users have been allocated to drug and to alcohol services on the basis of the government's assumptions, them there is probably a case for a reassessment.

Finally, on the basis of the data from this study, clear links exist between substance use and becoming and remaining homeless. Levels of drug use are high before the first episode of homelessness, and then they increase still further the longer homelessness lasts. In addition, dependency on drugs is common amongst the homeless population. Initiatives to tackle homelessness must therefore simultaneously deal with the drug problems of homeless people. Studies similar to the one described above are now needed in other areas of the UK, to assess if the startlingly high level of drug use by homeless people in London is repeated elsewhere.

*Corresponding author.

'Note that in this paper, `homeless' refers to all those who have no home, and includes those living in hostels for homeless people, in temporary accommodation provided for homeless people, and sleeping on the streets. `Sleeping rough' refers specifically to homeless people who are sleeping on the streets.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Crisis for funding support for the survey from which the data for this paper were taken, to staff from St. Mungo's Substance Use team for conducting the interviews with homeless people, and to Paul Griffiths at the National Addiction Centre, London for his valuable help on this project. The views expressed are those of the authors.

References

ACMD (Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs) (1998). Drug Misuse and the Environment. The Stationery Office, London.

American Psychiatric Association (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edn. APA, Washington DC.

Avramov, D. (Ed.) (1998). Youth Homelessness in the European Union. FEANTSA, Brussels.

Bines, W. (1994). The Health of Single Homeless People. Centre for Housing Policy, University of York, York. CRASH (Construction and Property Industry Charity for Single Homeless) (2000). Survey of Users of Winter

Shelters in London, Brighton, Bristol and Cambridge, December 1999-March 2000, under the Department

of the Environment, Transport and the Regions Rough Sleepers Unit. CRASH, London.

DETR (Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions) (1999). Coming in from the Cold: the

Government's Strategy on Rough Sleeping. Rough Sleepers Unit, DETR, London.

Downing-Orr, K. (1996). Alienation and Social Support: a Social Psychological Study of Homeless Young People in London and in Sydney. Averbury, Aldershot.

DTLR (Department for Transport, Local Government and the Regions) (2001). Coming in From the Cold:

Progress Report on the Government's Strategy on Rough Sleeping. Rough Sleepers Unit, DTLR, London. Ducq, H., Guesdon, I. and Roelandt, J.L. (1997). Psychiatric morbidity of homeless persons: a critical review

of the Anglo-Saxon literature. Encephale Revue de Psychiatrie Clinique Biologique et Therapeutique, 23(6),

420-420.

Farrell, M., Howes, S., Taylor, C., Lewis, G., Jenkins, R., Bebbington, P., Jarvis, M., Brugha, T., Gill, B. and

Meltzer, H. (1998). Substance Misuse and Psychiatric Comorbidity: An Overview of the OPCS National Psychiatric Morbidity Survey.

Fitzpatrick, S., Kemp, P. and Klinker, 5. (2000). Single Homelessness: a Review of the Research in Britain. The Policy Press, Bristol.

Fountain, J., Strang, J., Gossop, M., Farrell, M. and Griffiths, P. (2000). Diversion of prescribed drugs by drug users in treatment: anlaysis of the UK market and new data from London. Addiction, 95(3), 393-406.

Fountain, J. and Howes, S. (2001). Rough Sleeping, Substance Use and Service Provision in London. Final report to Crisis. Crisis/National Addiction Centre, London.

HSA (Housing Services Agency) (1999). The Outreach Directory: Annual Statistics 1998-1999. HSA, London. Hutson, S. and Liddiard, M. (1994). Youth Homelessness: the Construction of Social Issue. Macmillan, London.

Johnson, T.P., Freels, S.A., Parsons, J.A. and Vangeest, J.B. (1997). Substance abuse and homelessness: social selection or social adaptation? Addiction, 92(4), 437-445.

Neale, J. Drugs Users in Society. Palgrave, Basingstoke. (In Press).

Nyamathi, A., Bayley, L., Anderson, N., Keenan, C. and Leake, B. (1999). Perceived factors influencing the initiation of drug and alcohol use among homeless women and reported consequence of use. Women and Health, 29(2), 99-114.

Social Exclusion Unit (1998). Rough Sleeping: Report by the Social Exclusion Unit. Cabinet Office, London. RSU (Rough Sleepers Unit) (2000). 1999 Estimate of the number of people sleeping rough in England. Statistics provided by Rough Sleepers Unit to the authors.

Tackling Drugs to Build a Better Britain (1998). The Government's Ten-Year Strategy for Tackling Drug Misuse. The Stationery Office, London.

World Health Organisation (WHO) (1992). International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th edn. WHO, Geneva.

Wright, J.D. and Weber, E. (1987). Homelessness and Health. McGraw-Hill, Washington.