Dealing with Data

Drug Abuse

Dealing with Data

JANE FOUNTAIN*

* Jane Fountain is a writer and researcher working in London.

This chapter will discuss the strategies I devised to collect and analyse data whilst attempting to relate to the orthodoxy of research methodology texts. The study—my Ph.D. thesis—was of the social and econornic organization of a network of sixty-four cannabis dealers, whose operations ranged from selling several pounds of the drug a week for a profit to passing on one-sixteenth of an ounce to a friend occasionally, as a favour. I identified five levels of distribution: wholesaler, middleperson, retailer, and regular and occasional supplier.

It is surprising that there is little information available about the contemporary cannabis scene in Britain, given the drug's estimated one million users per years (ISDD 1990, p. 10), and the cost to the criminal-justice system of, in 1988 for instance, processing 26,111 individuals who were found guilty of offences involving it (Home Office 1989, Table 1.1). Sociologists might reasonably be expected to have taken advantage of such a massive example of deviant behaviour, but this has not been the case, with the result that the existing knowledge about cannabis users and dealers is dependent on outdated, theoretical, and anecdotal information. In the absence of more recent work, Becker (1963) and Young (1971) are too often regarded by social scientists as having provided the classic descriptions of an unchanged situation, yet since their studies, cannabis has gained a relative respectability as other illegal drugs became the focus of moral panics.

The behaviour of the dealers was described and analysed using combinations of explanations offered for it by the interactionist concepts of labelling, deviancy amplification, and the deviant career; subcultural theory; control theory; anomie-based theories; and by the dealers themselves. The research methodology illustrates the integration between what Jupp (1989, p. 178) calls the 'warring and intransigent fortresses' of the various theories of deviance, and also between theory and research methods, as the interactionist perspective also provided a major contribution to the methodology of the study: as Downes and Rock (1988, p. 186) say, interactionism is 'hesitant about planning and exposition, arguing that such work blinds one to the possibility of learning in the field . . . Interactionists would preserve their openness to the social world, being educated as they pursue research.'

Access

Getting In

As a working-class, tabloid-reading, politically right-wing, full-time housewife and mother from a small town, I had never seen an illegal drug, and had learnt to consider that people who used them were 'weirdos', 'hippies', and `drop-outs'. I was 30 years old before I actually saw people smoking cannabis, and was very surprised that the stereotypes could not be applied to them. I shed my naïvety and ceased to be shocked when joints were passed round with the same nonchalance that I passed round my home-made cakes. Then I moved to a city, got a job in further education teaching unemployed teenagers, and began to lead an increasingly middle-class, left-wing, life-style. When I was 36 I abandoned teaching to become a sociology undergraduate. En route, I met more cannabis users, very few of whom were weird, hippies, or had dropped out.

I met Chris and Sally at the home of a mutual friend, and soon discovered they were cannabis retailers. Initially, the 'evil pusher' image dominated my perceptions of them, but the more I got to know them, the more their deviations from it became apparent. Our friendship developed, and in the following two years I met some of their customers and other dealers. I had just completed a sociology degree and, still in academic mode, began to wonder whether there was potential in these contacts for a study of cannabis dealers, with the couple as my gatekeepers. I formulated a vague plan for this and asked them what they thought. They agreed to co-operate, and from the beginning were familiar with my aims and what I intended to do with the data.

I sat in Chris and Sally's house, where they did most of their trading, and observed the comings and goings of their contacts, asking questions, with their help, when we judged it appropriate; I accompanied the couple when they visited the dealers they bought from; I ate with them; I made good use of their spare bedroom; and joined them on many social occasions, too. My involvement in their lives led to varying degrees of contact with sixty-two other cannabis dealers at several distribution levels, and about seventy of the couple's non-dealing customers.

As I was not deceiving my gatekeepers about what I was researching and why, and particularly as they were both familiar with 'warts and all' sociological investigations, many of the problems of gatekeepers' control over access, chronicled by Hammersley and Atkinson (1983, pp. 63-76) were overcome. For example, the authors give illustrations of gatekeepers who wanted researchers present only when there was something 'normal' happening. However, dealers cannot predict when there will be run-of-the-mill buying and selling of cannabis and when something extraordinary will occur. Similarly unpredictable are what Hammersley and Atkinson call 'troublesome' and 'sensitive things', away from which the gatekeepers may wish to steer the researcher but in which the researcher may be most interested. If I happened to be with my gatekeepers when there was an extraordinary, troublesome, or sensitive incident, my friendship with them, and the lack of deception, meant that I was not steered away and, once I had shared such an experience with them, the gate was left open for further sharing. To illustrate: I was at Chris and Sally's one evening when it appeared that business was going to be slow, and we were discussing whether or not to go out for a drink. Chris said that before we did he would make quick phone-call to Brian, a dealer who had been collecting fresh supplies for the couple. Brian's flatmate answered the phone, and told Chris that Brian had been arrested. Therefore I was present as the couple panicked and discussed what do do, was with them while they did it, and was party to their discussions in the following weeks about how to minimize the risk of their own arrests.

Access to the rest of the network of dealers of which Chris and Sally were part was unproblematic: my gatekeepers made sure that I met every individual they did business with. I did not experience the problems Hammersley and Atkinson (pp. 78-88) discuss concerning 'blending in', because in the dealing world, if someone brings a friend along then their presence is unquestioned, as the newcomer is presumed to have been vetted before their introduction to the dealer. As Adler (1985, p. 14) conunents when two marijuana smugglers wrongly assumed she and her husband knew that their friend Dave was also a smuggler: 'They thought that anybody as close to Dave as we seemed to be undoubtedly knew the nature of his business.'

Getting Along

Many studies have involved field relations which go beyond a formal researcher—gatekeeper association: Klockars (1974, pp. 219-20), for instance, says of his relationship with his principal informant on fencing: came to like Vincent and he knew it. As time went on we became good friends.' In a study closely comparable to my own in terms of field relations and subject-matter, Adler discusses the friend—researcher—gatekeeper relationship (1985, pp. 11-28), believing that access to a group with something to hide (in her study, marijuana and cocaine traffickers) must of necessity be based on friendship. That basis enabled Adler 'to trade my friendship for their knowledge' (p. 27), and she gave her gatekeepers practical, as well as moral, support.

Polsky (1967) lays down often-quoted firm guide-lines for avoiding the moral, legal, and research dilemmas which he sees arising from such relationships, but in the field I found it difficult to 'draw the line' he advocates between myself and those I was studying. Consequently, one drawback of my relationship with Chris and Sally, and with other dealers I came to know well and like, was that I had to be constantly on my guard against ignoring or excusing aspects of my friends' behaviour that I considered irrunoral. Conversely, I met some dealers I did not like, and had to be on my guard again interpreting their behaviour in a negative way.

Warning of the dire effects of over-identification with the group being studied abound in the literature on participant observation, with the researcher exhorted to blend in with the setting to see things the way 'the natives' do, but not so much so as to lose their objectivity as an investigative outsider. In treading this fine line, researchers can deliberately employ empathy or an 'appreciative stance' when negotiating access to a group with which they have previously had little or no contact. This tactic, however, does not completely insulate them from their subjects: Fielding (1982, p. 90) found that the growth of his relationship with his primary contact in the 'unlovable' National Front 'caused me much reflection on the subject of my own politics and friendships'. I did not have the luxury of being able to consider how much empathy towards dealers and dealing I should display, because when I began the study I had been involved in Chris and Sally's lives for two years, and through them had got to know many other dealers. Some researchers are even closer to their field: Hobbs (1988, p. 7), for instance, used his status as an East Ender to give an insider account of the trading culture there, and says: 'Because of my background, I found nothing immoral or even unusual in the dealing and trading that I encountered.'

Sharrock and Anderson (1980, p. 22) have a solution to the problems of ethnographers' field-work practices, problems which they say stem from the 'illusory dilemma' of concentration on the separation of the worlds of the researcher and those being researched, where researchers begin with the premiss that their subjects' world is inaccessible to outsiders, but that members themselves are able to explain it. They propose a shift in focus which can be applied to my relationship with those dealers who knew the nature of the study and were my key informants: to treat the subject 'as regarding his [sic] own actions as objects of investigation by both himself and the researcher'. In this way, researchers and their subjects 'co-produce' the field-work: both have to discover what is going on and the meaning of events and activities they do not share. To approach dealers as a culture which had nothing in common with my own would not, I feel, have led to as full an explanation of their world as co-production of data did.

However, as I was attempting to 'co-produce' data with those dealers with whom I was most friendly, it was often difficult to distinguish between the 'friend' and 'respondent' roles in each of them, and the 'friend' and 'researcher' roles in myself, particularly as dealing is often a sociable activity. I envied, for example, Klatch (1988) at her Moral Majority conference and Van Maanen (1982) with his police officers, as they had constant reminders (respectively items on the agenda and a uniform) that, although they might be adopting a participant role (and in Van Maanen's case this included training as an officer and wearing the uniform), the field was clearly labelled as such. Sitting cosily watching television with Chris and Sally and another dealer who was a good friend of theirs, or spending the weekend camping with the couple and Brian at the Glastonbury Festival, where they sold cannabis for only a few hours a day, was hardly conducive to role-differentiation, although an aid to it was one which Van Maanen (p. 145) pinpoints: I did not have to live with the consequence of their actions as my informants did.

Gatekeeper Influence

Because I was not a novice in the setting, I could not employ any of the criteria for choosing my informants, as suggested by, for instance, Tremblay (1957), Dean et al. (1967), and Burgess (1982, p. 77), who warns that 'the "best" informants may be marginal to the setting under study'. However, it did not seem sensible, given my friendship with Chris and Sally and their willingness to help, to leave them in search of 'better' gatekeepers, so I deliberately made them the centre of the setting—the contacts all the other dealers in the study shared. Thus, as Liebow (1967) acknowledges Tally's influence on his study of the street-corner, I must also acknowledge that my gatekeepers were central to the account of the network I studied. Any other member could have been my gatekeeper to a different branch of it: in the extreme case, if the first co-operative dealer I had met had been an unemployed Hell's Angel, living in a squat, then I would probably have been researching a different group of people within a different culture, for as Blum et al. (1972, p. 155) discovered in their study of drug dealers, there is a 'strong tendency' for them to sell to those 'close to them in socioeconomic or life-style conditions'.

My gatekeepers influenced my methodology and the ethical consideration of how much I revealed to any individual (which I discuss in more detail later). Chris, Sally, and I debated whether I should reveal the reason for my presence to some of the people I was deceiving, but we decided to err on the side of caution. If dealers objected to being researched, then they might refuse to do business with the couple, or insist that I was not present. If I carried on the deception, then at least I had a chance of getting some data. A further influence on my methodology was that the almost constant presence of Chris and/or Sally during the data-gathering period meant that certain things I wanted to know could never be asked directly. For instance, if I wanted to know how much profit a wholesaler made when selling to retailers, it was unlikely they would tell me in front of the very people from whom they were making the profit. Such data had to be obtained by waiting for snippets of information to come up of their own accord and piecing them together with the aid of a calculator.

In time, I came to regard Chris and Sally as my research assistants rather than as my gatekeepers, for during my periods in the field we were collaborators, like Whyte (1955) and the famous Doc.

Researcher Influence

I influenced what happened in the field, too—sometimes deliberately. For example, if my gatekeepers had little contact with a particular dealer, I would encourage the couple to contact them in order for me to meet the person. However, once we were in the presence of that dealer, I do not believe my influence on the subsequent behaviour was any more (or less) than that of any researcher employing what Adler (1985, p. 27) aptly calls the 'delicate combination of overt and covert roles', and which is discussed thoroughly in the many texts on participant observation (such as Burgess 1982; Hammersley and Atkinson 1983; Lofland and Lofland 1984).

I also made some dealers more aware of aspects of dealing they had only vaguely considered previously. When I monitored the time Chris and Sally spent with customers and the profit they made from each deal, for instance, Chris commented that he had never given much thought to the amount of time spent on a transaction and the surrounding cultural niceties. He also became obsessed with the daily profits, constantly asking me the amount and how it compared with that of previous days. If he thought profits were declining he would make proposals about how to increase them—by devising tactics to attract more customers, for instance. Similarly, when I discussed the risk of arrest with Squeezer, he commented: 'You've made me really paranoid now', perhaps leading to a change in his behaviour regarding the precautions he took against arrest.

As field-work progressed and I became increasingly familiar with the dealers and the way they ran their operations, opportunities to use my influence abounded and I had to guard against it. For instance, Bill and Squeezer both began selling cannabis during the study, and I monitored their progress closely. However, I also took an interest in them in an almost maternal way (discussing them with Chris and Sally, I referred to them as `rny boys'), and, as such, was tempted to offer Squeezer, particularly, advice on how to run his operation more efficiently and profitably.

Research Methods and Design

My research design followed that suggested by grounded theory (Glaser and Strauss 1967). After a year of writing down anything and everything which happened in the field, and filing and cross-referencing it under various headings, I devised an interview schedule to help me to identify patterns in the data, suggest further lines of inquiry, and organize and present it systematically. However, while the interview schedule could be labelled 'un-structured', the techniques I employed for soliciting answers to the questions are not so neatly defined. Even 'interviews' with the same individual were carried out both overtly and covertly, and some were completed by asking respondents a few questions at every meeting over the entire field-work period. I also used an eclectic combination of subsidiary methods: these were primarily observation and the subsequent data from field-notes; monitoring of some aspects of some dealers' operations; and information gathered from people who knew the respondent (but which I did not use unless it was possible to check it with another source, or, preferably, the respondent themselves). I also referred to relevant documents, literature, and statistics where appropriate.

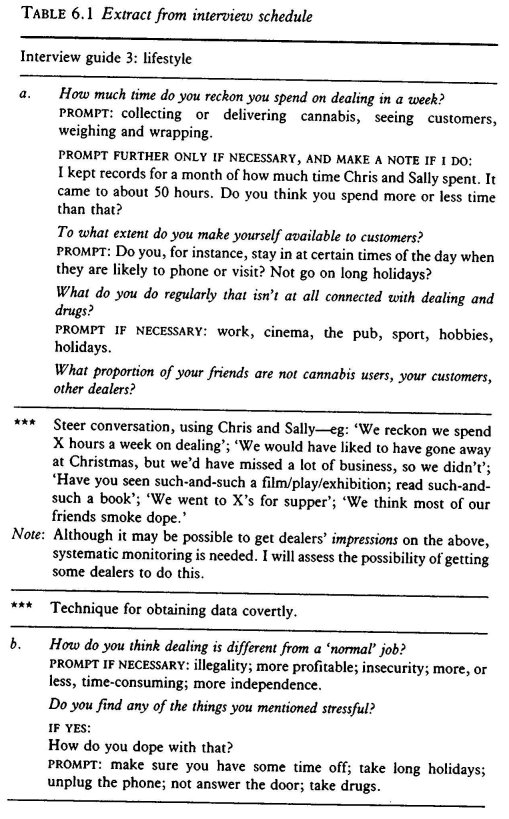

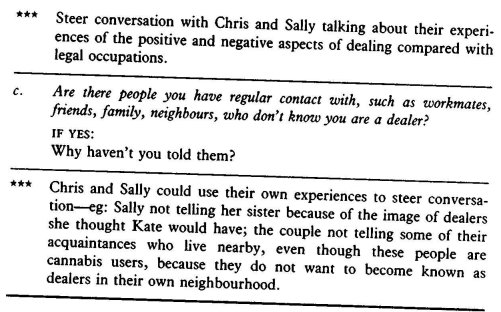

The complete interview schedule consists of twelve sections, running to twenty-six pages: Table 6.1 illustrates just one section of it. The schedule is consistent with the data matrices system of Miles and Huberman (1984), and designed to cope with data-gathering often in small units, from various sources, over a period of time until a response is recorded to as many questions as possible. Even in the overt interview situation it was not usually completed in the presence of the respondent, but filled in from recall later, when 'answers' often took up several pages.

During the early stages of field-work, I divided the respondents into three groups: those who knew I was researching aspects of cannabis distribution and had agreed to co-operate (although how much each individual knew varied considerably); those who did not know I was doing research on anything at all; and those whom I told I was doing research on `Enterpise Culture', and gave the following cover-story:

I'm doing a Ph.D. on Enterprise Culture in Thatcher's Britain, where people like Richard Branson, Anita Roddick of The Body Shop, and the woman who started The Sock Shop chain, are held up as fine examples of people who saw a gap in the market, and used their entrepreneurial skills to make money out of it--an inspiration to us all.

I've been looking at people operating on a much smaller scale: for instance, I've talked to a woman who does all the cooking for your dinner party, and a man who has set himself up as a gardener. I've looked at some people who are on the Enterprise Allowance Scheme, and are seriously trying to get an idea to make money off the ground—such as a jewellery-maker and a photographer.

I've also found some people who are on the Scheme but not really serious about starting a business--they're just doing it to keep the DHSS off their backs for a year: for example, I met someone who's got an Enterprise Allowance to be a music promoter, but all he's doing is getting bookings for his own band, which he was doing anyway.

I've looked at the enterprises of people who are on the fiddle, like minicab drivers who are moonlighting from another job, and not declaring the income from their driving, and people who are signing on but doing something like window-cleaning, or mending cars, or wheeling and dealing in something, as well. I've talked to a couple of people on the game, and a woman who runs an 'intimate telephone conversation' service.

Finally, I'm talking to dealers--like Chris and Sally—and I hoped you'd help me by telling me a few things about the way the dealing business operates. You don't have to worry about what I'm going to write about you—I shan't be saying anything which will lead to anyone being able to find out who you are.

Observation

I spent two-and-a-half years in the field, where contact with the majority of dealers took place in Chris and Sally's house, although occasionally I met dealers in their own homes, in public places, and on social occasions. My gatekeepers never prevented me from accompanying them wherever I wished, but when, where, and how often I met dealers depended to a large extent on when, where, and how often Chris and Sally met them. This limitation applied particularly to the middlepersons and wholesalers whom the couple met only when they needed fresh supplies: I saw some dealers at these levels only once every six to eight weeks, but other retailers and suppliers were in more frequent contact with my gatekeepers-- weekly or fortnightly—and therefore with me. These meetings often lasted an hour or so and, over the field-work period, enabled me to get to know some participants very well.

The network was based on trading relationships, not friendship, and Chris and Sally, and therefore I, lost contact with some dealers--sometimes temporarily, sometimes permanently—and a few dealers had only sporadic contact with Chris and Sally because the couple were not their usual suppliers. An ever-present threat to access was that any dealer could be arrested at any time and stop dealing. In the event, however, this only happened to one dealer, Brian, who served a prison sentence for the offence. As he is an old friend of Chris's, though, it was possible to remain in contact with him.

For three thirty-day periods I closely monitored Chris and Sally's dealing activities. I was able to do this by staying at their house, so that I could record who visited them to buy and sell cannabis; how long each visitor stayed; the time spent on weighing-up and wrapping the drug; how much was bought and sold; and the profit made or amount spent on every deal. During these monitoring periods I also accompanied the couple when they left the house on cannabis business and recorded details of those transactions too. I was also able to monitor, in less detail, the amount sold and the profit made by several other retailers.

Overt Interviewing

I had not foreseen any major problems in getting information from those dealers who knew the nature of my rsearch and had agreed to co-operate: they had been enthusiastic about 'telling it like it is', and had appeared reassured that they would remain anonymous, not least because the individuals I selected for this category were, generally, those with whom I had become most friendly. However, when I began to ask questions from the interview schedule it became clear that it was going to be difficult for me, and for them, to make the transition from friends to formal interviewer/respondent.

I piloted the interview schedule with Chris. It was not a complete success: while he had been more than happy to tell me informally anything I wished to know about himself and about dealing, he became very flippant when I sat with him with pen and paper in hand. For instance, when I asked him how he worked out the price he charged for cannabis, he replied that he charged 'whatever I think I can get away with', which I knew from previous conversations and observation was not the way he operated. During the interview Chris began to read a newspaper and complained that the interview was taking too long, even though we had agreed to set the time aside for it.

After my experience with Chris I decided that I would try a pilot of just one section of it with Squeezer, who knew about the research in much less detail than Chris and who, I suspected, would not treat it in such a cavalier fashion. This second pilot presented different problems. Squeezer, who had been keen to co-operate when I was planning the project, was clearly uncomfortable when he saw I was writing the answers down, and became anxious about what I was going to do with the answers and whether he would be able to be identified from them. Yet he, like Chris, had always been happy to ta& to me about dealing previously; had suggested aspects of cannabis buying and selling for investigation; and had even offered to 'write something about it' for me.

I became worried that I would be unable to get useful data by the overt interviewing method, and that dealers would stop talking even informally to me. I decided to abandon interviewing with the schedule in my hand, and writing down the answers in front of the respondent. Instead, I isolated sections of the interview schedule which I could not complete by observation and casual conversation, and made lists of what I needed to know or what I needed to confirm from my observations. Every tirne I saw the dealer I would check the list beforehand, and ask a few specific questions or steer the conversation to get the information I wanted. Once I had the answers I would make a comment such as: 'You realize I'm going to write this down when you've gone, don't you?' No dealer in this group ever objected; often, they would say something along the lines of 'you may as well ask me a few more questions then', and I could openly consult my list.

This method was clearly more acceptable than the formal interview to those dealers with whom I had formed friendly relationships: answers could be seen by them to be part of general friend-to-friend conversation, over which they felt they had some control, and I felt that it led to more spontaneous answers as the influence of my researcher role was minimized. Okely (1983, p. 45) found a similar solution when formal interviews with travellers failed to get her the data she needed:

It was more informative to merge into the surroundings than alter them as an inquisitor . . . Towards the end of the fieldwork I pushed myself to ask questions, but invariably the response was unproductive, except among a few close associates. Even then, answers dried up, once it appeared that my questions no longer arose from spontaneous puzzlement and that I was making other forms of discussion impossible.

Covert Interviewing

During the compilation of the interview schedule I had planned 'to steer the conversation with Chris and Sally's help'. Often this strategy worked well, but when it did not I felt I should abandon that particular question until a much later contact, rather than risk 'blowing my cover' by being obsessively interested in a particular aspect of their life or dealing activities. As Agar (1980, p. 456) says:

. . . you should not have to ask. To be accepted in the streets is to hip; to be hip is to be knowledgeable; to be knowledgeable is to be capable of understanding what is going on on the basis of minimal cues. So to ask a question is to show that you are not acceptable and this creates problems in a relationship when you have just been introduced to somebody.

In the field, however, I was saved from being grossly unhip, unknowledgeable and unacceptable by several factors:

• dealers enjoyed 'talking shop' with other dealers;

• the majority of the dealers in the covert interviewing category were those at middleperson and wholesaler level. Chris and Sally were retailers, and the higher-level dealers often passed on advice and related anecdotes to the 'lower orders' with little prompting;

• the middlepersons and wholesalers in the network were men. Sally and I exploited their paternalism by displaying wide-eyed naivety which flattered them and enabled us to ask very unhip questions (Easterday et al. 1977, usefully discuss the roles of female researchers in predominantly male fields);

• some dealers were my friends before I began the research, and I met most of the others in the network many times: therefore, it was not necessary for me to ask questions when we had just been introduced, nor even tell them I was a researcher.

Consequently, it was only certain sensitive questions, such as finances or ciminal records (other than for drug offences, which no dealer seemed to mind talking about) which presented difficulties in covert interviewing. If all my attempts to solicit such data failed, I had to accept that some dealers' interview schedules were never going to be completely filled in, or that data I had obtained about an individual from another source could not be checked by asking the dealers themselves.

Initially, some of the data I had imagined would be easy to obtain covertly presented difficulties. For example, as part of the background picture I wanted to build up of each individual, there was a question in the schedule about education. When appropriate I would chat about my own, or Chris and/or Sally about theirs, and often the respondent would react as I had planned. Bryn, however, with whom I piloted covert interviewing, did not, and I felt I could not keep returning to the subject and cause him to wonder why I was displaying such an intense interest in his educational background. Later I realized that I had entered into my spy persona too wholeheartedly—in the course of an 'ordinary' conversation it would not have been unusual to have asked him outright whether he had been to a university. Incidents such as this improved my technique in later covert interviews.

Interviews using the Enterprise Culture Cover-Story

The dealer with whom I chose to pilot this strategy was Frenchie. It was only partly successful. He displayed only a very tnild interest in enterprise culture and in Chris and Sally's co-operation with me, and I felt it was inappropriate to ask for his. 'Interviews' with him then became a combination of using the cover-story and the covert strategy. A further problem was that Frenchie used a variety of illegal drugs, and the level of his participation in, and response to, what was going on around him, fluctuated wildly. The influence of drug-use by respondents on the collection of data was not a major problem in this study, however.

I persevered with the cover-story and had more success with other dealers. When I talked about 'people who are on the fiddle' and prostitution—or before—some dealers suggested that I included cannabis dealing in the Ph.D. too. If this happened I would say admiringly 'that's a good idea', and ask them for suggestions for themes, which usually led to the dealers revealing something of their own activities. This strategy worked well. If dealers did not respond in this way, and depending on the reaction I thought I would get, I continued the cover-story by saying I wanted to include enterprises such as dealing. Chris and/or Sally were able to confirm my credentials, and that I was trustworthy, by telling the dealer that they were helping me with my research. Even if I felt it was inappropriate to ask the dealer to help personally, they often would comment at this point that they 'could tell me a thing or two', and so I could proceed to ask them questions of a general nature whenever I had contact with them: they would invariably illustrate the answers with their own experiences. I used the cover-story with about a dozen dealers, and even if I decided not to ask for their co-operation, the route to asking specific questions about dealing was smoother and faster than the 'steering the conversation' technique I employed in totally covert interviewing.

Thus, while in theory I had neatly categorized strategies for soliciting information from each dealer, in the field the edges between the categories were somewhat blurred. A further complication was that, as field-work progressed, I had to remember at what stage in which category each dealer was, because this changed: as I got to know some individuals better, I was able (after consultation with Chris and Sally) to reveal more about the study to them.

Because I was afraid I would lose access to the network of dealers, I had begun field-work using the methods just described while waiting for my Ph.D. proposals to be accepted by the Economic and Social Research Council and the University of Surrey. Initially my knowledge of research methods was somewhat sketchy, and my main concern was to get everything that happened written down. However, once I officially began the study, attended lectures on research methods, and read textbooks on research methodology, I realized that whichever method was used to gather data, its validity and my interpretation of it had to be assessed, particularly as there are no other studies of British cannabis dealers with which to compare it.

Validity of Data and Interpretation

Fielding and Fielding (1986, p. 24) say: 'when pressed about validity and reliability, qualitative researchers ultimately resort to their own estirnation of the strength of the cited data or interpretation; we have heard such responses many times. To avoid reliance on this last resort, it is possible to compile a long list of validity checks--from, for example, Burgess (1982) and Hammersley and Atkinson (1983). While I cannot claim to have ticked off every item, I did not often have to resort to the inadequacy of `the assertion of privileged insight' (Fielding and Fielding, p. 25): the multi-method techniques I used in the two-and-a-half years I spent in the field enabled me to operate a cross-checking procedure when faced with data from solicited and unsolicited accounts, field-notes from observation, and hearsay.

I could discuss proposals which had arisen from the data with several of my informants, and this often led to the generation of further proposals and lines of inquiry. However, asking them to validate my interpretations of specific aspects of their own behaviour and accounts of incidents was problematic. As Hanunersley and Atkinson (1983, p. 196) point out, the researcher has to recognize 'that it may be in a person's interests to misrepresent or misdescribe his or her own actions, or to counter the interpretations of the ethnographer'.

Where interpretations clashed, I had to be aware of the consequences for my relationship with the dealer concerned, not least because there was a danger that they would withdraw their co-operation. For example, I noted that the first tinie Phil visited Chris and Sally, he arrived with two friends and a handful of marijuana, and as he walked through the door asked Sally if she had any 'skins' (cigarette papers) so they could smoke it. The trio then sat down as if preparing for a long smoking session, and it was clear that they had already been using the drug before their arrival. In less than two minutes Phil and his friends had unknowingly violated several of Chris and Sally's rules for customer behaviour. Chris tactfully explained that they did not want 'hoards of people trooping through the door' because they were very risk-conscious, and were worried that neighbours may have seen them, the marijuana in Phil's hand, and noticed that the three were under the influence of it. He added that he and Sally were often too busy to spend time smoking cannabis or marijuana with customers—`if we did, we'd never get anything else done.' The trio nodded amicably, bought their cannabis from the couple, and left. On his next visit Phil's behaviour had changed considerably, and he obeyed his new dealers' rules to the letter.

My interpretation of this incident was that on his first visit Phil had behaved as he did because he had learnt from his previous dealers, and from his own experiences selling cannabis and cocaine, that this was what was expected of him, and that he had changed his behaviour according to the expectations of his new dealers. I felt I knew him well enough to ask him if this proposition was correct. However, as his visits to Chris and Sally's house only ever lasted about ten minutes, I had to force the pace and put the question somewhat out of the blue. Even though Phil was aware that I was studying dealing, he misinterpreted what I was saying—or I presented it badly—and thought I was accusing him of being a `druggie'. He was clearly offended, and it took several weeks for my relationship with him to recover. Chris made it clear he disapproved of what I had done, too: 'He looked really freaked when you suddenly came out with it like that.'

Thereafter, if I. suspected offence might be taken, I confined the respondent-validation strategy to asking respondents for comments on other respondents' behaviour and accounts. I hasten to add that I did not intend to rely on data gathered solely by this 'garden-fence' method, but I made use of the normal gossip which occurs amongst friends and acquaintances to back up what I already knew or suspected, and then incorporated it into my observation and questioning of a particular dealer. An illustration of this is when I asked Squeezer how his business was going, at a time when I had calculated that he was making very little profit, and he replied that he was 'doing quite well'. A few days later I casually asked a close friend of his the same question. She replied: 'He says he's not doing very well—he says he smokes most of the profits.' The next time I saw Squeezer I asked him if his cannabis use had increased since he began dealing: it had.

The time I spent with the network of dealers alleviated much of the danger to which one-off and formal interviews and susceptible. As Whyte (1973, pp. 114-16) says, an informant's current emotional state, values, attitudes, sentiments, and opinions may not be consistent and are highly situational, but I was able to check, periodically, the continuing validity of what respondents did or told me, and note any changes, for, as Hammersley and Atkinson (1983, p. 193) warn: 'What people say and do is produced in the context of a developing sequence of interaction. If we ignore what has already occurred or what follows, we are in danger of drawing the wrong conclusions.'

Burgess (1982) and Hammersley and Atkinson also demand consideration of the following for checks on distortion in informants' accounts of incidents: the reliability of the informant; the plausibility of the account; the place of the informant in the setting; and comparison with others' accounts of the same incident.

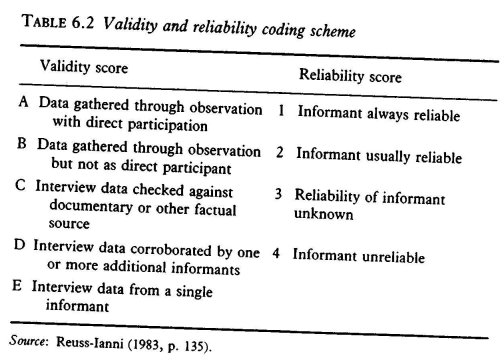

Checks on the reliability of an informant can be formalized, and for this I found the coding scheme devised by Reuss-Ianni (1983, p. 135—reproduced in Table 6.2) helpful. Where my data did not score at least D-2, I attempted to better it with information from other sources. If this proved impossible but I still made use of the data, I pointed out its possible invalidity and unreliability.

The plausibility of an account can be checked by the researcher who is established in the setting under study. Here, I believe, 'privileged insight' plays an important—but not the only—part. For example, I found Frenchie's hints that his frequent visits to Spain to work for illegal drug traffickers implausible, not only because his recklessness, heavy drug use, and criminal record for drug offences, would, I thought, deter anyone with a lot to lose from employing him, but also because he was clearly not earning any money there: he once phoned Chris and Sally from Spain to say he had run out of money, and asked for £250 to be sent; on another occasion he phoned from a Spanish airport and asked Chris to organize a return ticket for him; and he once returned with no money, and borrowed £100 from Chris.

The place of the informants in the setting can influence how they, give an account of their world. For example, the study identified a five-tier cannabis distribution pyramid, and many of the dealers thought that those above them in it spent all their time using and selling the drug, and were part of a violent, multi-drug-using, criminal, subculture. As I had contact with every level, though, I discovered that this was a false impression.

Some accounts of incidents given by respondents could be confirmed by asking others who were present, but it was not always possible. Bryn, for instance, told me of events which happened up to twenty-five years ago, and which are relevant to current aspects of his dealing operation, but as I did not have contact with anyone who knew him at that time I was unable to check the information. In such cases, if I wanted to use the data I would try to return to the subject at a later date, to see if the respondents' accounts tallied with their previous telling of it.

Ethical Considerations

After I had been collecting data for about nine months, I started to write the methodology chapter of my thesis. Until I came to the 'Ethics' section, I had been only dimly aware of the condemnation covert observation receives from some social scientists. For guidance on research techniques I had been concentrating on participant (or semi-participant) observation studies (such as Fielding 1981; Holdaway 1982; Okely 1983; Adler 1985; Hobbs 1988), and textbooks on ethnography (such as Hammersley and Atkinson 1983; Lofland and Lofland 1984) which, although recognizing the ethical dilemmas of the covert observer, did not condemn the technique. For example, Lofland and Lofland (pp. 43-4), while commenting on the attention ethical considerations have attracted from 'specialists in ethics' and from field-workers 'agonising over their behavior and relationships', say: 'Without in any way denigrating these efforts or belittling the honestly expressed moral anguish of some researchers, it seems to us that too much can be made of the fieldwork setting as involving special and particular ethical problems.'

I was complacent, then, that my methodology (including what I thought were rather clever ways to extract information covertly from dealers) and the checks I had built into it regarding objectivity and validity would result in a faithful representation of the dealers, and would therefore be acceptable to social science. I turned to the ethical guide-lines of the Social Research Association (1983) and the collection of texts on covert participant observation edited by Bulmer (1982), thinking I could dismiss the issue easily. My smugness evaporated when I read of the many horns on the many ethical dilemmas facing social-science researchers generally and semi-covert, semi-participant observers like myself in particular. However, rather than list them all, I will discuss the two aspects of my study with which I was especially concerned: that my varying degrees of deception often left me feeling guilty—not because of the condemnation the lack of informed consent receives from some social scientists, but because I was deceiving the dealers; and that by exposing hitherto unresearched aspects of the distribution of cannabis, I might harm not only the sixty-four dealers I was researching, but also all the others in Britain.

Feeling Guilty

Although by the end of the study only half-a-dozen of the sixty-four dealers remained unaware that I was doing any sort of research at all, only my two gatekeepers had enough information about the study for them to be able to gauge whether or not co-operating with me could harm them. The others were at best misinformed, and at worst lied to. My initial reaction on learning that this was unacceptable to some social scientists was a defiant: 'Well, social science knows almost nothing about cannabis dealers, and this was the only way I could tell them,.' Ultimately, this remains the justification for my methodology, but this does not mean that all was therefore plain sailing, as Bulmer (1982, p. 246) recognizes: 'Dilemmas and choices will continue to face the field researcher that dogmatic statements of "should" and "must" will not eliminate. The complexity of practical decision-making will continue to dog the steps of the sociologist using observational methods.'

Consequently, even the strongest critics of covert research rarely suggest that a phenomenon should not be studied if deception of subjects is involved. For example, Bulmer (pp. 235-6) sums up the contributions to the collection on the merits and demerits of covert participant observation thus: 'Complete concealment of the research . . . may rarely if ever be justified, but the converse—that total openness is in all circumstances desirable or possible—does not follow.'

I examined the justifications for the ethical compromises made by other covert researchers and the literature cataloguing the issues, and discovered that the majority of commentators ultimately conclude (although they reach that conclusion by different routes) that the ethical dilemmas of an ethnographer will require compromise to 'solve', much of it dependent on decisions made by the individual researcher. Reynolds (1982, p. 213) pinpoints the issue as I saw it:

To conform to the highest standards of individual morality in temporary personal exchanges at the expense of examining important, critical scientific and societal problems may not be the choice preferred by a number of investigators. It is for each social scientist to decide how they wish to serve society: as a personal moral exemplar or as a source of useful and valued information.

Nonetheless, placing myself firmly in the latter category did not assuage the guilt I felt. Adler (1985, p. 25) maintains that the covert researcher's role in the field makes such encounters with ethical dilemmas and 'pangs of guilt' necessary because:

They can never fully align themselves with their subjects while maintaining their identity and personal commitments to the scientific [I would substitute 'academic] community. Ethical dilenirnas, then, are directly related to the amount of deception researchers use in gathering the data, and the degree to which they have accepted such acts as necessary and therefore neutralized them.

Adler (p. 26) found that despite the 'universal presence of covert behavior' throughout her setting, she and her husband still 'felt a sense of betrayal every time we ran home to write research notes on observations we had made under the guise of innocent participants'. Like Adler's, the setting I studied also operated on a basis of secrecy, and like her gatekeepers, my own sometimes advocated and condoned my covert approach, because of the possible effect on their business if one of their buyers or sellers objected. Even though I gradually revealed more about the study to some of the dealers, I was hindered by the reluctance of even some willing respondents to be formally reminded at every contact that they were being studied (Squeezer, for instance, as detailed earlier). Despite these justifica-tions, I could not escape feeling like a betrayer sometirnes, too.

Often, I felt like the head of MI5 on an assignment with two of my staff. The planning and execution of such missions was exciting but, particularly if they were successful, I was sometimes left feeling guilty. For example, Chris, Sally, and I spent several hours at Bryn's flat one day, during which he made us lunch and gave us, without too much prompting, many details about himself and his dealing activities, unaware that I was researching the subject. When we left, we gleefully hurried off to the nearest café, and wrote it all down. After the euphoria over all the information we had obtained died down, however, I felt that we had abused the hospitality of this friendly man, who had so clearly enjoyed our company. We agreed that we would not have spent so long with him, listening to his long, rambling tales, if they had not been so useful for research purposes. We did it again, though.

I also felt guilty because I was pleased when dealers had negative experiences. For instance, my first thought on hearing that Brian had been arrested; that there was a severe shortage of cannabis; that Chris and Sally had been sold some cannabis of inferior quality; and that Bill had been badly beaten up and his stocks of cannabis and cash stolen, was 'what a brilliant research opportunity!'

Bulmer (1982, pp. 232-3) says that one of the situations where covert methods can be justified is 'retrospective participant observa-tion', based on the researcher's own experiences as a member of the field: he cites the studies of Becker the dance musician, and Polsky the pool hustler as examples. Lofland and Lofland (1984, p. 22), say that such researchers do seem to suffer less guilt, too: 'if the research project arises after you have become part of the setting—a frequent corollary of "starting where you are"—the moral onus seems less severe.' Certainly, the guilt I felt was not overwhelming—indeed, I often felt guilty for not feeling guilty, at, for example, simulating friendship when talking to Brian about his arrest, attending his trial, and visiting him in prison.

Another justification for covert observation methods comes from Shils (1982, p. 271), who, although a strong critic of the method, says that it is necessary where those being studied are crminals, although he adds: 'Their necessity on behalf of social order does not diminish their morally objectionable character; it simply outweighs it.' I considered hiding behind the motive of helping society to control cannabis dealers in order to justify my methodology. But this would not have been true. The seeds of the study, as described at the beginning of this chapter, were sown because the cannabis users and dealers I met did not conform to the popular stereotype, and sociology had done little to investigate its accuracy.

Publish and Be Damned?

Whilst Bulmer (1982, p. 241) says that researchers using observa-tional techniques should not model themselves on secret agents or investigative journalists, such research reveals the identities of the subjects, whereas I gave considerable thought to disguising them. This involved more than merely using pseudonyms and not revealing the name of the city where the dealers operate. I did not write dates, times, nor place-names in my field-notes; I confined my field-note headings to 'Week 4: in Brian's flat', to indicate temporal and situational context; I wrote up most field-notes within twenty-four hours of collecting them, destroyed some of the originals, and stored many of the write-ups at the house of a trusted friend; when compiling frequency counts (on, for example, the dealers' ages, housing situations, legitimate occupations, and education history), I made sure that a profile of a particular individual could not be built up from them; and when discussing the precautions dealers take against arrest and a dealing conviction, I omitted those which I thought were particularly ingenious. These precautions meant that some highly relevant data was omitted—often at the expense of emphasizing a particular point or providing a 'good' story. They also meant that I became very anxious in case I had included details which might lead to the identification of the dealers by outsiders. My anxiety knew no bounds: for instance, I quoted Sally saying that her profits from selling cannabis meant that she could make impulse buys without worrying about the cost. She gave an example: `I'm going through Marks and Sparks and I fancy some prawns, and I can buy loads.' I became obsessed with the prawns that were usually in her fridge, and that if she was arrested, her relationship with me would be revealed; my thesis scrutinized by the police; the quote and the prawns in her fridge connected; everything I had written about 'Sally' used against her; and the whole network traced—all because of those dratted prawns.

I discouraged dealers from writing down my phone-number and address, and I did not write down theirs. I did this because I was aware that if any dealer was under surveillance by the police, and I, because of my association with them, was arrested, my data would be an aid to the collection of evidence against them. A further reason for removing evidence was that I was aware of the potential an arrested dealer might see in a defence of helping me with my enquiries, so I was also proteCting myself by this tactic. Whilst Whyte (1955), Becker (1963), Polsky (1967), and Adler (1985) are among those who have found illegal actions by themselves to be 'a necessary or helpful component of the research' (Adler, p. 24), like them, I did not imagine that this made me immune from charges of witnessing crimes and withholding information. To avoid police attention on myself as someone who knew many dealers, I therefore did not publicize the nature of my research any more than necessary, and used the cover-story with some of my acquintances—including police officers I met at criminology conferences.

That said, most of the dealers will recognize themselves and others if they read the study. I find Adler's comment-1 hope I cause them no embarrassment' (1985, a chapter note, p. 158)--too optimistic an apology, and feel the issue merits further consideration than many ethnographers give to it, for anonymity also serves to protect them from recriminations. The respondents who were most aware that I was studying them included those with whom I was, and remain, most friendly: with some, I hope that I will be able to rely on that friendship to avoid their long-term wrath, but Brian may not forgive me for pretending friendship, even though he knew I was carrying out the study. Of those who knew I was researching something, but were vague about the details, Frenchie will very probably object to being used throughout the study as an example of an inefficient and risk-taking dealer. The reaction of the half-dozen respondents whom I never told I was doing research on anything at all, but who would recognize themselves in the study, worries me considerably.

While the study sits on a library shelf, with access to it restricted, I am confident that those dealers who did not know I was studying them will not see it. Several of the others have begun to ask me if they can read it, though, and the time is rapidly approaching when I can no longer put them off by saying 'when it's finished', or by giving them verbal edited highlights. Some will find not only considerable details about themselves, but also that they have contributed to data on, for example, the sort of people who distribute cannabis; their motivation for doing so; how they operate; the profits they make; the precautions they take against arrest; and the effect of their own and/or other dealers' arrests on themselves, and on the network of which they are part. On the library shelf, I am confident that it will not harm them or other cannabis dealers, but if it is published I envisage having to face up to the responsibility of having provided the law-enforcement agencies and policy-makers with useful information which could contribute to their arrests.

Dilemmas continue to dog me, then. If I decide to attempt to have the study published—and I probably shall—I risk harming the dealers and losing some of my friends. jupp (1989, pp. 157-8) advises that I should have a academic and professional commitment to publication, and (as a general rule, provided the researcher has taken whatever steps as are reasonable to ensure anonymity there is no reason to refrain from publication'. I may be exaggerating the harm I will cause: interviews with police officers by Campbell (1990) and Graef (1990) show that those who have some experience of dealers at the levels of this study are aware of the inaccuracy of the stereotypical 'drug barons' and 'evil pushers', in spite of government policy statements which perpetuate the images. The effect on my personal relationships may be more severe. I wish I could believe Lofland and Lofland (1984, pp. 157-8) who recognize the dilemma, but say: 'Most people do not seem to care very much about scholarly analyses that are written about them. Many don't get around to reading them even when they are published . . . The use of psuedonyms and a scholarly mode of writing tend to minimise the participants' interest . .

I fear Hughes (1960, p. xii) has identified the more likely outcome of the publication of my research: 'hatred . . . is visited almost daily upon the person who reports on the behavior of people he [sic] has lived among; and it is not so much the writing of the report, as the very act of thinking in such objective terms that disturbs the people observed.'

References

Adler, P. A. (1985). Wheeling and Dealing: An Ethnography of an Upper-Level Drug Dealing and Smuggling Communiv (Washington DC: Columbia University Press).

Agar, M. (1980). Professional Stranger (New York: Academic Press).

Becker, H. S. (1963). Outsiders: Studies in the Sociology of Deviance (Glencoe: The Free Press).

Blum, R. H. et al. (1972). The Dream Sellers: Perspectives on drug dealers (New York: Jossey-Bass).

Bulmer, M. (1982). (ed.), Social Research Ethics: An Examination of the Merits of Covert Participant Observation (London: Macmillan).

Burgess, R. G. (1982). (ed.), Field Research: A Sourcebook and Field Manual (London: Allen & Unwin).

Campbell, D. (1990). That was Business, This is Personal: The Changing Faces of Professional Crime (London: Secker & Warburg).

Dean, J. P., Eichorn, R. L., and Dean, L. R. (1967). 'Fruitful Informants for Intensive Interviewing' in J. T. Doby, (ed.) An Introduction to Social Research (2nd edn., New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts).

Downes, D. and Rock, P. (1988). Understanding Deviance: A Guide to the Sociology of Crime and Rule-Breaking (2nd edn., Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Easterday, L., Papademas, D., Schorr, L., and Valentine, C. (1977). 'The Making of a Female Researcher: Role problems in fieldwork' (in Burgess 1982).

Fielding, N. G. (1981). The National Front (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul).

— (1982). 'Observational Research on the National Front' (in Bulmer 1982).

— and Fielding, J. L. (1986). Linking Data, Sage University Paper Series on Qualitative Research Methods, vol. 4 (Beverly Hills, Calif Sage).

Glaser, B. G. and Strauss, A. L. (1967). The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research (New York: Aldine).

Graef, R. (1990). Talking Blues: The Police in Their Own Words (London: Fontana).

Hammersley, M. and Atkinson, P. (1983). Ethnography: Principles in practice (London: Tavistock).

Hobbs, D. (1988). Doing the Business: Entrepreneurship, the Working Class, and Detectives in the East End of London (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Holdaway, S. (1982). 'An Inside Job: A Case study of Covert Research on the Police' (in Buttner 1982).

Home Office (1989). Home office Statistical Bulktin, Issue 30/89. Statistics on the Misuse of Drugs: Seizures and Offenders Dealt With, United Kingdom, 1988 (London: Government Statistical Service).

Hughes, E. C. (1%0). 'Introduction: The Place of Field-Work in Social Science', in B. Junker (eds.), Field Work: An Introduction to Social Sciences (Chicago, Ill.: University of Chicago Press).

Institute for the Study of Drug Dependence (1990). Drug Misuse in Britain: National Audit of Drug Misuse Statistics (London: ISDD).

Jupp, V. (1989). Methods of Criminological Research, Comtemporary Social Research Series 19 (London: Unwin Hyman).

Klatch, R. E. (1988). 'The Methodological Problems of Studying a Politically Resistant Conununity', Studies in Qualitative Methodology, 1 .

Klockars, C. B. (1974). The Professional Fence (London: Tavistock).

Liebow, E. (1967). Tally's Corner (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul).

Lofland, J. and Lofland, L. H. (1984). Analysing Social Settings: A guide to Qualitative Observation and Analysis (2nd edn., Belmont, Calif.: Wadsworth).

Miles, M. B. and Huberman, A. M. (1984). Qualitative Data Analysis (London: Sage).

Okely, J. (1983). The Traveller-Gypsies (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Polsky, N. (1967). Hustlers, Beats, and Others (Harmondsworth: Penguin (1971) edn.).

Reuss-Ianni, E. (1983). Two Cultures of Policing (London: Transaction).

Reynolds, P. D. (1982). 'Moral Judgements: Strategies for Analysis with Application to Covert Participant Observation' (in Bulmer 1982).

Sharrock, W. W. and Anderson, R. J. (1980). On the Demise of the Native: Scmte Observations on and a Proposal for Ethnography (University of Manchester Department of Sociology: Occasional Paper No. 5).

Shils, E. (1982). 'Social Inquiry and the Autonomy of the Individual' (in Bultner 1982).

Social Research Association (1983). Directory of Members Handbook 198314 (London: Social Research Association).

Tremblay, M.-A. (1957). The Key Informant Technique: A Non-Ethno graphic approach' (in Burgess 1982).

Van Maanen, J. (1982). 'Fieldwork on the Beat', In J. Van Maanen, J. M. Dabbs, and R. R. Faulkner, Varieties of Qualitative Research. Studying Organizations, Innovations in Methodology 5 (Beverly Hills, Calif • Sage).

Whyte, W. F. (1955). Street Corner Society (Chicago, Ill.: University of Chicago Press).

— (1973). 'Interviewing in Field Research' (in Burgess 1982).

Young, J. (1971). The Drugtakers: The Social Meaning of Drug Use (London, Paladin).

Last Updated (Thursday, 17 February 2011 17:46)