Any spare change? The income and expenditure of substance users who are sleeping rough: results from a survey in London

Drug Abuse

Any spare change? The income and expenditure of substance users who are sleeping rough: results from a survey in London

Jane Fountain, BA (Hans), PhD

Principal Lecturer (Research), Centre for Ethnicity and Health, University of Central Lancashire, do DrugScope, 32-36 Loman Street, London SE1 OEE, UK.

Telephone: +44 (0)20 7928 1211

Fax: +44 (0)20 7922 8780

Samantha Howes, BSc

Researcher, National Addiction Centre

Colin Taylor

Statistician, National Addiction Centre

Professor John Strang MBBS, FRCPsych, MD

Director, National Addiction Centre

Maudsley Hospital/ Institute of Psychiatry, 4 Windsor Walk, London SE5 8AF, UK.

ABSTRACT

A survey of the substance use of 389 homeless people included questions on current income and expenditure. The two sources of incorne most often reported were state benefits and begging. Those whose main substance was heroin or crack cocaine were more likely to have a larger financial expenditure, and to obtain this income from criminal activities, than those whose main substance was another drug or alcohol. By far the most commonly-cited main items of expenditure were drugs and alcohol. The findings are discussed in terms of current interventions and service development.

KEY WORDS

homelessness, income, expenditure, drugs, alcohol, crime

In the UK, there have been attempts, through street counts, to ascertain the numbers sleeping rough (on the streets). In June 2000, it was estimated that 1180 people slept rough in England on any one night — 535 of them in London (Rough Sleepers Unit (RSU), 2000). However, as this population is not stable, the numbers sleeping rough annually are probably five times higher than on any one night (Social Exclusion Unit, 1998). In 1999, the Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions (DETR) set a target of reducing these numbers 'to as near zero as possible, and by at least two-thirds, by 2002' (DETR, 1999 p. 7). This target was reported to have been achieved in December 2001 (Rough Sleepers Unit, 2001).

A variety of risk factors are associated with homelessness', including offending behaviour and substance use (for example, Evans, 1996; Randall & Brown, 1999). Crisis points which trigger homelessness include leaving prison and an increase in drug and alcohol use. Once homeless, Klee & Reid (1998) suggest, young people use drugs — particularly opiates — to cope with the stress of a homeless lifestyle, and Randall & Brown (1999) point out that homelessness itself makes it more likely that ex-offenders will re-offend. Unemployment adds to the problems of homeless people: as Fitzpatrick et al. (2000 p. 33) summarise, in a review of the relevant research, the "no home-no job" cycle for homeless people has long been recognised. Satisfying basic survival needs generally precludes employment for those sleeping rough.' Thus, those at the extreme of homelessness — sleeping rough — are likely to be part of an environment in which substance use and criminal activity are common, and an income from employment is rare.

A major survey was undertaken of the drug and alcohol use of people recently or currently sleeping rough in London, and also provided the data for this paper. Fountain et aL (In press) report that 83% (324) of a sample of 389 had used a drug in the month prior to the interview and 66% (215) of them were dependent on the main drug they had used. In addition, in the last month, 68% (264) of the sample had used alcohol, 45% (120) of them cited it as their main substance and 37% (97) of them were dependent on it. The uptake of drug and alcohol services amongst this sample was low (other than needle exchanges), despite over half the current drug users and a third of the current alcohol users wanting help with their substance use (Fountain et al., 2003). The high prevalence of drug and alcohol problems amongst this sample not only has implications for the provision of drug and alcohol services, but also raises the question of how their substance use is financed. Data that answer this question are reported in this paper.

Methods

The survey was established to explore the relationship between homelessness and substance use amongst people sleeping rough in London.

Structured interviews were conducted with a sample who had slept rough for at least six nights in the previous six months. The period of six months was chosen so as to capture those who were in a cold weather shelter at the rime of the interview, but who were sleeping rough previously (and in many cases were likely to be returning to sleeping rough when the cold weather shelter closed). Interviews were conducted from January to October 2000, in 20 different locations within inner London, including hostels, cold weather shelters, 'rolling' (ie, temporary) shelters, day centres, drop-in centres, and in the street. Drug and alcohol users were not targeted as a specific sub-group. Interviewers were recruited from a team working with homeless people, who were specially trained to administer a structured questionnaire with some linked open-ended questions. Measures to gather data on current income and expenditure were specially constructed for the study, and an analysis of these is the focus of this paper.

Results

The sample consisted of 389 homeless people. Almost half (48%, 187) had slept rough for more than six months in the year before the interview, and 17% (67) the night before. Almost two-thirds of the sample had been homeless for six years or longer. Eighty-one per cent were male and 19% female, with an average age of 31.1 (range 17-72). Their gender, age, race and the inner London borough where they last slept rough were typical of all those sleeping rough in London during the previous year (for a detailed description of the sample, see Fountain et al., In press).

Income was a widespread problem: when asked about the areas with which they currently wanted help, the response most often given was help to find permanent accommodation (91%, 356), followed by financial problems (46%, 180). In addition, 44% (177) wanted help with drug problems and 23% (88) with alcohol problems.

1. Current income

Respondents were asked structured questions about where they obtained money and what they spent it on. A wide range of income, ranging from .±:,0 per day (2%, 8) to £300 per day (0.5%, 2) was reported, rendering the average of £274 per week of limited real meaning (mean £39.10, median £20.00, mode £7, Std. deviation 47.44). Overall, 17% (68) of the sample had an income of less than £50 per week, 58% (225) had more than £100 per week and 16% (63) had more than £500 per week.

Sources of income

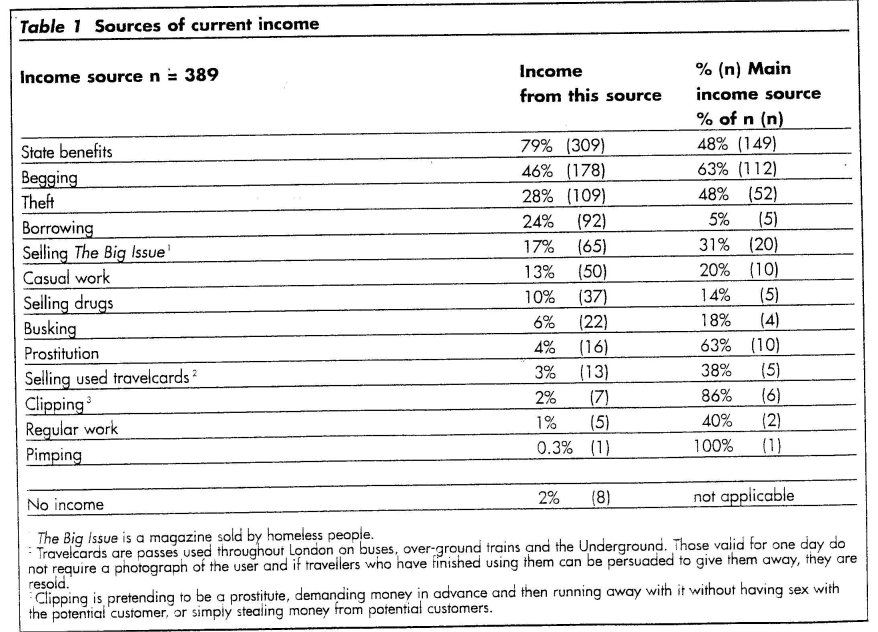

Respondents were asked for the sources of their current income and which was the main source. These are shown in Table 1.

The legal income most often reported (by 79%, 309) was state benefits and this was the main income source for 48% (149) of those in receipt of it. Few were employed: 13% (50) earned money from casual work, but only 20% (10) of them reported this as their main source of income. Even fewer reported an income from regular work (1%, 5) and this was the main source of income for less than half of them (40%, 2).

The most often reported illegal method of generating income was begging. Just under half (46%, 178) of the sample made money from begging, and it was the main source of income for almost two-thirds of these (63%, 112). Twenty-eight per cent (109) made money from theft and this was the main income source for 48% (52) of them. Far fewer respondents reported an income from other illegal activities.

More of the whole sample got money from state benefits (79%, 309) and from begging (46%, 178) than from any other source. These were also reported as the main sources of income more than any other: state benefits for 38% (149) of respondents and begging for 29% (112).

Income in relation to substance use

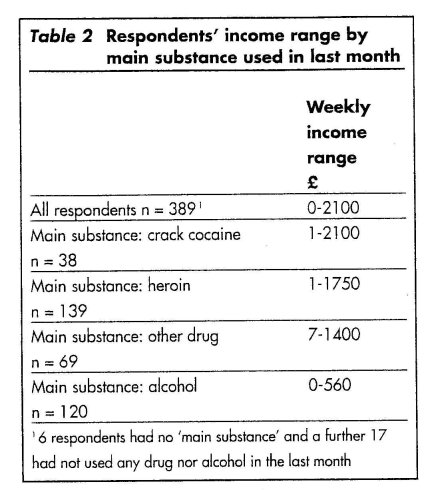

The data on income were analysed in relation to the main substance respondents had used in the last month. Table 2 shows that this was most often reported to be heroin, followed by alcohol. Six per cent (23) of respondents had either not used any drug nor alcohol in the last month (4%, 17 of the whole sample), or had used so relatively little that they were unable to cite a 'main substance' (2%, 6).

The range of income varied according to the main drug used, as shown in Table 2, which reveals that the highest income was reported by those whose main drugs were crack cocaine and heroin. As noted above, the range of income was too wide for a meaningful average. For example, although the average weekly income of those whose main drug was heroin was £436, the range was L1-1,750.

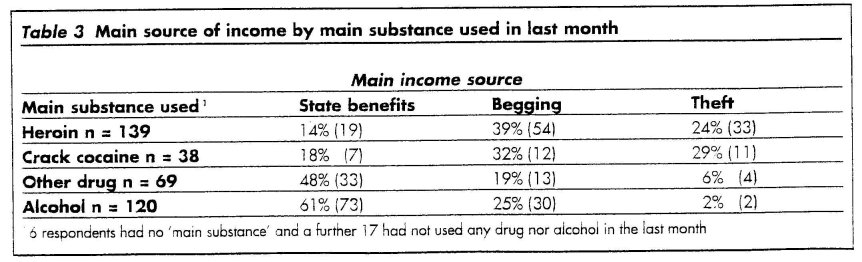

The sources of income also varied according to the main substance used. For example, as shown by Table 3, begging was the main income source of 39% (54) of those whose main substance was heroin and 32% (12) of those whose main substance was crack cocaine. Begging was the main source of income for a smaller proportion of those whose main substance was another drug or alcohol.

Respondents most likely to obtain their main income from state benefits were those whose main substance was a drug other than heroin or crack cocaine or, particularly, alcohol. Sixty-one per cent (73) of those whose main substance was alcohol, and 48% (33) of those whose main substance was another drug had a main income from state benefits. Theft was the main income of more of those who cited their main drug as heroin (24%, 33) or crack cocaine (29%, 11) than it was for those whose main s'ubstance was another drug or alcohol.

Main income source in relation to duration of homelessness

For most of this sample, their homeless status was a chronic condition. Eighteen per cent (70) had been homeless for less than two years; 20% (76) for three to five years; 26% (102) for six to ten years; and 36% (139) for more than ten years (data were missing in two cases).

The longer respondents had been homeless, the more likely it was that begging was their main income source. Of the 112 whose main income was from begging, 20% (14) had been homeless for two years or less; 26% (20) for between three and five years; 28% (29) for between six and ten years; and 35% (49) for more than ten years.

The main income source of 13% (52) of the whole ample was theft and, again, was most likely to be cited as a main source by those who had been homeless for more than five years: by 15% (8) of those who had been homeless for two years or less; 21% (11) for three to five years; 35% (18) for six to ten years; and 29% (15) for more than ten years.

The less time respondents had been homeless, the more likely it was that their main income source was state benefits. Forty-four per cent (64) of the 146 who had been homeless for five years or less gave this as their main income source, whereas 35% (85) of the 241 who had been homeless for six years or more did so.

2. Current expenditure

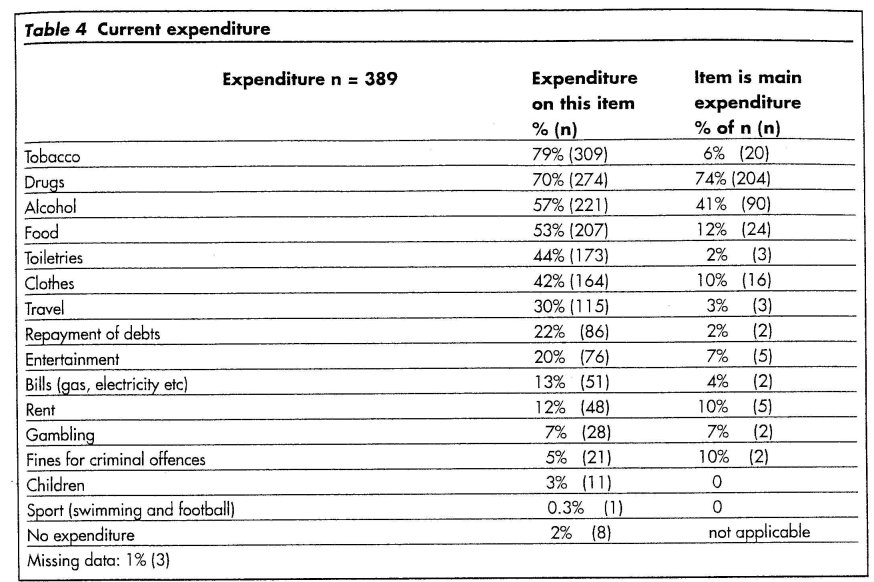

As shown in Table 4, the item of expenditure cited most often by the whole sample was tobacco, followed by drugs, alcohol, and food. However, by far the most commonly-cited main items of expenditure were drugs and alcohol. Of the whole sample, 52% (204) said their biggest expenditure was drugs and 23% (90) that it was alcohol. Almost three-quarters (74%, 204) of those who bought drugs on the illicit market cited it as their main expenditure, as did 41% (90) of those who spent money on alcohol. No item other than drugs or alcohol was cited as the main one by more than 6% of the whole sample.

Discussion

The respondents who were the subjects of the study discussed in this paper represent the extreme of homelessness — sleeping rough. This lifestyle is not conducive to employment and is likely to have not only been triggered by substance use and crime, but also exacerbates these behaviours. The sample's extensive use of drugs and alcohol and their involvement in fund-generating crime is therefore, whilst clearly a cause for concern and a challenge for drug, alcohol and homeless services, not entirely surprising.

The data presented in this paper should be seen in the context of other findings from the same study in order that stereotypes and stigmatisation of a group with severe social, economic, and substance use problems are not reinforced. In particular, we have found that major drug and alcohol problems are common amongst people sleeping rough; that there is a strong link between homelessness and substance use; and that substance use increases with the length of time a person has been homeless (Fountain et at. In press).

"we have found that major drug and alcohol problems are common amongst people sleeping rough; that there is a strong link between homelessness and substance use; and that substance use increases with the length of time a person has been homeless"

"This lifestyle is not conducive to employment and is likely to have not only been triggered by substance use and crime, but also exacerbates these behaviours."

Some homeless drug users — particularly those entrenched in rough sleeping and substance use — are not motivated to change. One obstacle to change is that temporary and emergency accommodation services are reluctant to accept drug users for a variety of reasons, which include the legal implications, especially after the Wintercomfort case in which two workers . were imprisoned after drug dealing had taken place on the premises where they worked (Shapiro, 2000). Consequently, drug use by clients in accommodation services for homeless people may be covert, in order to avoid eviction (Fountain &. Howes, 2001). There is a need for more accommodation services that support those who continue to use drugs until they are motivated to seek help, in order that their drug use does not remain hidden and so that interventions — including harm reduction initiatives — can be implemented. Many homeless drug users will require long-term contact, with non-coercive services, in order to build their motivation to change.

Initiatives to tackle the crimes of homeless substance users are likely to succeed only if there is simultaneous success in tackling their homelessness and their substance use problems. A multi-agency approach to drug users who are sleeping rough has been increasingly adopted in the UK, but, as pointed out by Fitzpatrick et al. (2000 p. 46), use of this model may only succeed in big city settings with relatively large populations of potential clients. Needs assessments should be conducted in other areas to assess if the startlingly high level of drug use by homeless people in London revealed by this study is seen elsewhere.

The strategy to tackle rough sleeping (DETR, 1999) has gone some way to recognising that measures to reduce rough sleeping must simultaneously tackle substance use. The measures to reduce rough 6leeping have resulted in the numbers reported to have fallen considerably (RSU, 2001) and initiatives to tackle the substance use of those entrenched in a rough sleeping lifestyle have been introduced. For example, in 2000, the Department of Health funded the drug and alcohol specific grant whereby the RSU set up nine projects across England designed to help named drug and alcohol users. However, the long-term outcomes of such interventions are as yet unknown: any current successes should not preclude consideration of possible ways of maintaining and increasing their effectiveness.

Those newly homeless should be particularly targeted, before they become entrenched in a rough sleeping lifestyle in which substance use and crime to fund it are key features.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Crisis (a charity working for homeless .people) for funding support for the survey from which the data for this paper were taken, and to staff from St Mungo's Substance Use Team for conducting the interviews with homeless people. At the National Addiction Centre, Paul Griffiths and John Marsden are thanked for their valuable help on the project. The views expressed are those of the authors.

References

Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions (1999) Coming in from the cold: the government's strategy on rough sleeping. London: Rough Sleepers Unit, Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions.

Evans, A. (1996) We don't choose to be homeless. Report to the National Inquiry into Preventing Youth Homelessness. London: CHAR.

Fitzpatrick, S., Kemp, P., Klinker, S. (2000) Single homelessness: a review of the research in Britain. Bristol: The Policy Press.

Fountain, J. & Howes, S. (2001) Rough sleeping, substance use and service provision in London. Final report to Crisis. London: National Addiction Centre/ Crisis.

Fountain, J., Howes, S., Marsden, J., Taylor, C., Strang, J. (In press) Drugs and alcohol and the link with homelessness: results from a survey of homeless people in London. Addiction Research and Theory

Fountain, J., Howes, S., Strang, J. (2003) Unmet drug and alcohol service needs of homeless people in London: a complex issue. Substance Use and Misuse 38 (3-6) 379-395.

Klee, H. & Reid, P. (1998) Drug use among the young homeless: coping through self-medication. Health 2 (2) 115-134.

Randall, G. & Brown, S. (1999) Prevention is better than cure: new solutions to street homelessness from Crisis. London: Crisis.

Rough Sleepers Unit. (2000) 1999 estimate of the number of people sleeping rough in England. Statistics provided by Rough Sleepers Unit to the authors.

Rough Sleepers Unit. (2001) Government meets target on reducing rough sleeping. Press notice, 3 December 2001.

Shapiro, H. (2000) Wintercomfort: The price of trust. Druglink 15 (2) 4-7.

Social Exclusion Unit. (1998) Rough Sleeping: Report fry the Social Exclusion Unit. London: Cabinet Office.

Last Updated (Tuesday, 08 February 2011 15:36)