|

Although historically there has been a great deal of sociological research on gangs, there has been little empirical attention paid to the issue of gang involvement in drug trafficking. Most of the research that has been carried out also has not focused on those gang members most involved in the drug trade, that is those who present the major concerns for public policy in the area. Further, there has been a lack of integration of findings from the small number of studies that have been reported. Due in part to the recency of the problem of gang drug trafficking and, in particular, gang involvement in the "crack" cocaine trade, this state of the literature has been an impediment to the development of effective social policy. In a very preliminary effort to address these issues, we have sought to synthesize major findings of some of the recent studies and to expand upon this literature by identifying social and legal factors associated with core members of gangs involved in drug trafficking. The study is based on all cases of individuals identified by one substation of the Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department as central figures in drug gang activity in the city. The findings from our analysis of these cases are compared with those of other recent studies and implications for policy reform are discussed.

The Literature

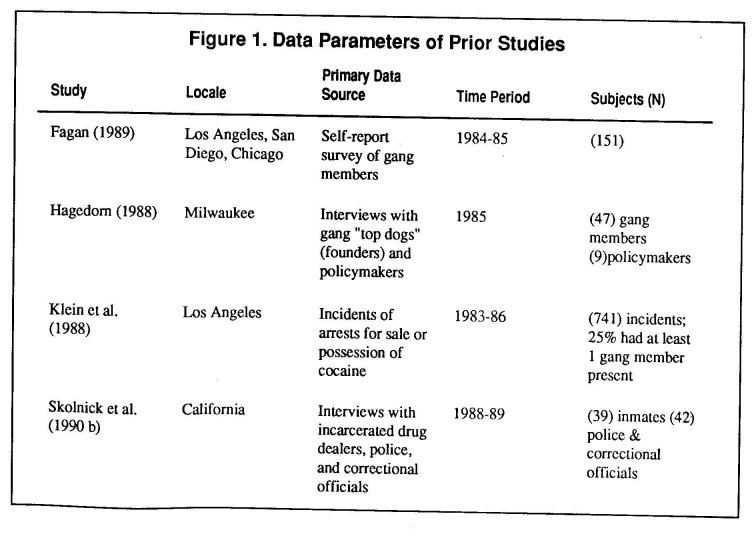

Recent studies of gang involvement in drug trafficking have concentrated on the problem in West Coast (Klein et al. 1988; Fagan 1989, Skolnick et al. 1990 a and b) and MidWestern (Fagan 1989; Hagedorn 1988) cities (see Figure 1.). It has been suggested that much of the problem originated in Los Angeles and that gang members have migrated to other cities because of increased law enforcement activities and a decreasing profit margin from cocaine in the Los Angeles area (see Skolnick et al. 1990 a). The studies cover the period 1983 to the present and are based on data from self-report surveys (Fagan 1989) and interviews with gang members in the community (Hagedorn 1988), from arrest records for possession and sale of cocaine (Klein et al. 1988), and from interviews with incarcerated dealers and criminal justice officials (Skolnick et al. 1990 a and b). The studies have apparently come about as a result of the 1980s development of crack cocaine and its 1984 large-scale introduction into the drug market (Hagedorn 1988), and because of subsequent law enforcement and media attention to the problem as one central to gang activity. The findings from some of these studies correspond with law enforcement and public conceptions of gang involvement in drug trafficking, while others do not. This may be, in part, an artifact of the different methods employed in the studies as well as of the time periods and locales in which they were conducted.

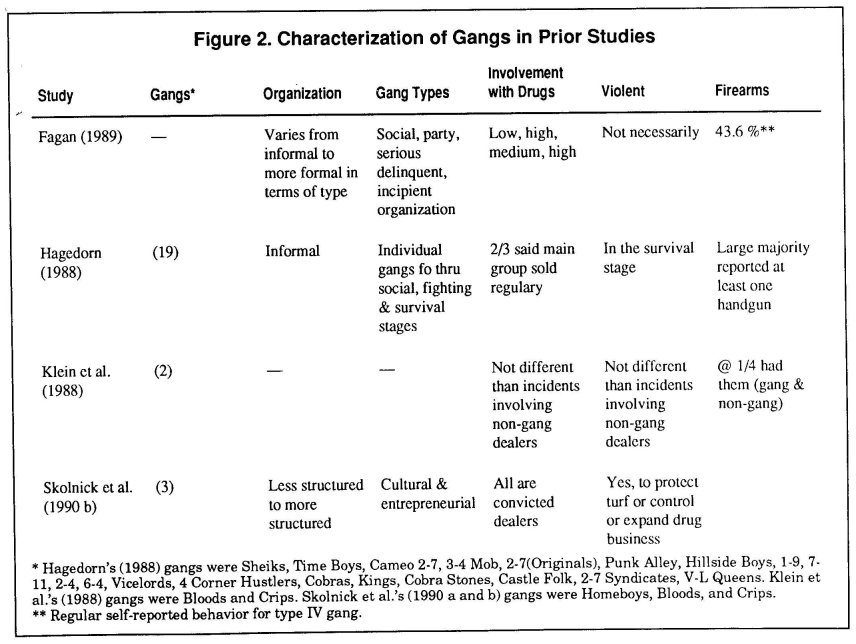

The media and law enforcement portrayal of gangs has been one of increased involvement with drug dealing and related problems of violence. Gang members have been depicted as predatory offenders, often in possession of weapons and involved in shootings to control or expand their drug trade. The literature both supports (Skolnick et al. 1990 b) and negates (Klein et al. 1988; Fagan 1989; Hagedorn 1988) this image (see Figure 2). Although there is not full agreement among researchers in this area (see Klein et al. 1988), the available studies generally point to a higher incidence of drugs and drug dealing within these groups (see especially Hagedorn 1988 and Skolnick et al. 1990 b). The studies also suggest that such gangs are more or less structured entities, whose type of organization is dependent upon their extent of involvement with drugs and criminal activity. The greater the extent of such involvement, the more the structure of the gang reflects protection of the drug market (see especially Fagan 1989; Skolnick et al. 1990 a and b). In this regard, Skolnick and his associates (1990 b) distinguish between "cultural" and "entrepreneurial" gangs, the latter being those organized to best control and expand their drug business. The studies do not generally support the popular imagery that such gangs are necessarily violent, although they do point to the prevalence of firearms among gang members.

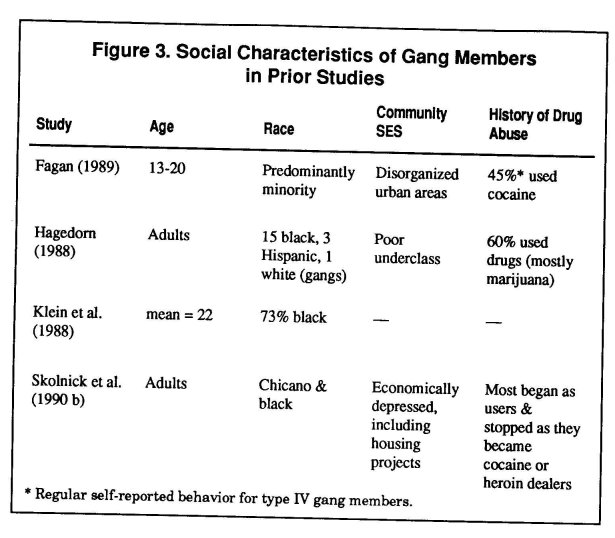

Recent studies have also addressed the social background of gang members (see Figure 3). The findings suggest that these groups are becoming increasingly made up of young adult, minority males from disorganized urban areas. They often have records of crime and regularly use drugs themselves. Because of a depressed and changing urban market structure, gang members are less frequently maturing out of gangs into the labor force, and appear to be using the gang as an alternative means of economic survival (Moore 1978; Hagedorn 1988). They are comprised almost entirely of an underclass of black and Hispanic males who live out their lives in the economically depressed neighborhoods and housing projects of American cities.

Hispanic gangs are more likely to be "cultural gangs," defending their neighborhood turf with little concern for economic gain; while black gangs are more likely to be "entrepreneurial gangs," exploitative of their neighborhoods for business profit (Hagedorn 1988; Skolnick et al. 1990 b). Most gang members have histories of drug abuse, although some discontinue their use as they progress to the demands of dealing cocaine and heroin (see Skolnick et al. 1990 b).

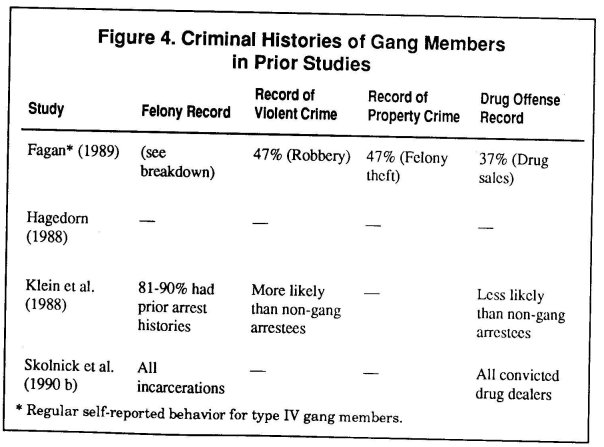

Depending upon the sampling frames, the studies show significant differences in the extent of criminal involvement of gang members (see Figure 4). Fagan's (1989) self-report study revealed that about half of the respondents involved in the more highly organized gangs had engaged in felony violent and property crimes, and that slightly more than a third had dealt cocaine. He states that "for virtually all crime types and drug categories, frequent participation by gang members in this study exceeds self-reports of involvement in similar behavior among non-gang youth" (p. 648). Even more dramatic in terms of nondrug related offenses, Klein and his associate's (1988) study of incidents of arrest for cocaine possession and dealing found that between 81 and 90 percent of gang members had histories of an arrest for a prior felony, and were more likely to have had a prior record of violent crime than non-gang offenders. This latter finding is especially significant given that gang members were on the average five years younger than those arrested in non-gang related incidents. More consistent with Klein's general argument, however, gang members were found to be less likely than non-gang members to have been previously arrested for a drug offense.

The Present Study

We now turn to our study of gangs in Las Vegas. Here we will attempt to expand upon the literature by identifying certain social and legal characteristics of core gang members and important relationships among these characteristics. It is our assumption that this segment of the more general population of gangs may differ in respects that have implications for social policy in the area. While previous studies (Fagan 1989; Klein and Maxon 1989; Spergel 1989) have noted such differences, there remains need for systematic analyses of the backgrounds and activities of core gang members. Studies of gangs based on samples that have included those who are marginally involved in such activity would presumably produce findings at considerable variance with the population of greatest public concern. If policy is to be effective in the area, it must clearly identify the specific nature of the problem and target its programs of prevention and control accordingly.

The Data

The data for our study consist of information obtained on 47 persons identified by the Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department as central figures in the four major gangs involved in dealing drugs in the city. A substation of the Department which had jurisdiction over the areas in which these gangs operated had in 1988 developed a list of gang members whose pictures are displayed on a substation bulletin board, as a "Rouges' Gallery" of sorts, under headings of the gang names. This display is kept current and is accompanied by descriptive information on the background of gang members. These individuals were members of the West Coast Bloods, the Pirus (Bloods), the Donna Street (Crips), and the Gerson Park Kingsmen. We emphasize that these are not all of the gangs in Las Vegas, but rather those that have been identified as posing the greatest threat to the community from the standpoint of gang drug trafficking and related problems of violence. While other black and Hispanic gangs have also been identified as dealing drugs, such dealing is thought to be confined primarily to their own groups and, therefore, is not seen as posing as great a threat to the community at large.

The information complied on the members of the four gangs included their date and place of birth, race, sex, employment status, address, history of drug abuse, tattoos, possession of firearms, prior offense record, and whether they had ever been a victim of a violent crime. This information is complemented with field observations made during several "ride alongs" with the Department officer involved in this project, and by his own observations and experiences of several years of police work with gangs.

The oldest of the gangs is the Gerson Park Kingsmen. They developed in the mid 1970s as a social group, primarily organized around playing basketball, and progressed to a fighting group as they encountered conflict and rejection at school. They are said to have introduced PCP and rock cocaine into the city. The Donna Street Crips is the second oldest gang. A rather loosely knit gang that has also evolved from a social group, they are said to produce considerable fear in the community as they openly display their colors and gang hand signs. The Pirus, a blood gang, was apparently started by two blood gang members who in 1983 were forced out of Los Angeles by the California Youth Authority. This gang's beginnings are described as quick, violent, and accompanied by frequent robberies. The most recent gang, the West Coast Bloods, started in 1986 is characterized as violent and having been involved in multiple shootings. Recently, the West Coast Bloods and the Pirus have openly challenged the Donna Street Crips.

These gangs are all located in low-income, government-subsidized housing projects that are situated in a north central part of the city. The project areas are located in a "zone in transition" as a large population of Mormon families moved out of the area just prior to the development of the housing projects in the early 1960s. Following this out-migration, the area became physically isolated by the building of major freeways lined with barbed wire fences and large irrigation systems near the southern borders of the projects.

Design for Analysis

The information compiled by the police was provided to the researchers for computer entry and analysis. These data will be presented in the section that follows. The presentation will include the social characteristics of gang members, the nature and level of their involvement in gang activities, and their record of prior criminal offenses. Where possible, these characteristics will be compared with those found in previous studies of gang members. We will also attempt to discern the social factors predictive of gang involvement, and the effects of such involvement on drug trafficking and related criminal activities. Chi-square analysis will be used as the test of statistical significance and, given the small N, relationships will be accepted as significant at the .10 level. It should be clear that, in the absence of longitudinal data, this analysis will not allow us to establish causal relationships among the various independent and dependent variables. It will only provide some indication of the relationships that exist among these variables. Any policy implications that are inferred from our findings must therefore be considered tentative.

Findings

Social Background

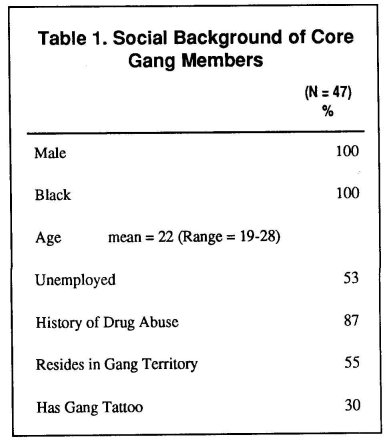

First, we will look at the social composition of the gangs. The background characteristics of the core members in our study are presented in Table 1. The figures show that all the members were black males between the ages of 19 ancr28, with the average age being 22 years. Slightly more than half were unemployed, while those who were employed were employed almost entirely in menial jobs in Las Vegas hotels and casinos, such as kitchen workers, bus persons, and porters. Eighty-seven percent were thought to have had histories of drug abuse, a figure that is somewhat larger than those reported in most previous studies.' While our findings on age would appear to be consistent with those of prior studies, the exclusively black composition of our sample is a function of our sampling method, that is our use of data on only those persons identified by the police at a sub-station that services the area in which black gangs are concentrated.

We are also interested in the extent to which gang members were involved in their gangs. It was thought that indicators of such involvement would include residing within the gang territory and having a gang tattoo. Table 1 also addresses these indicators of involvement. The data show that slightly more than half of the core gang members lived within their "turf" and about a third had gang tattoos.

Criminal Record

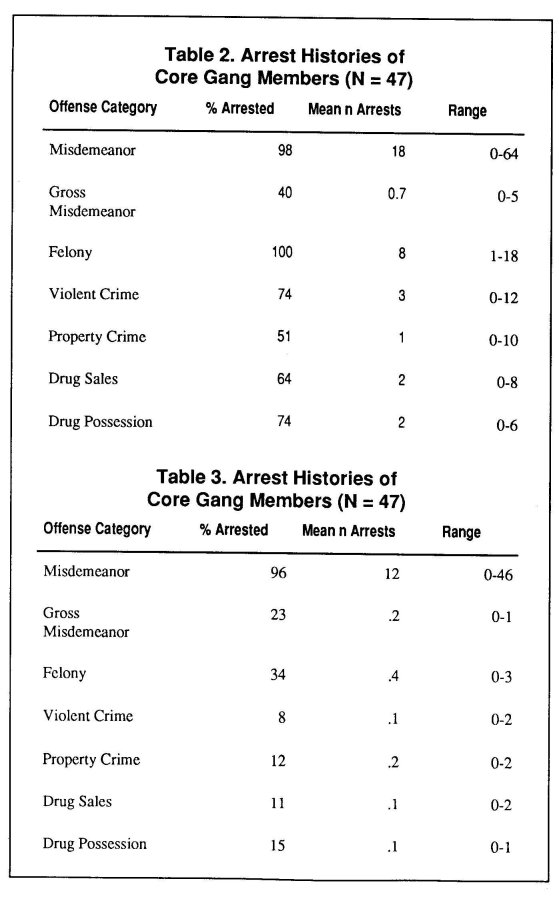

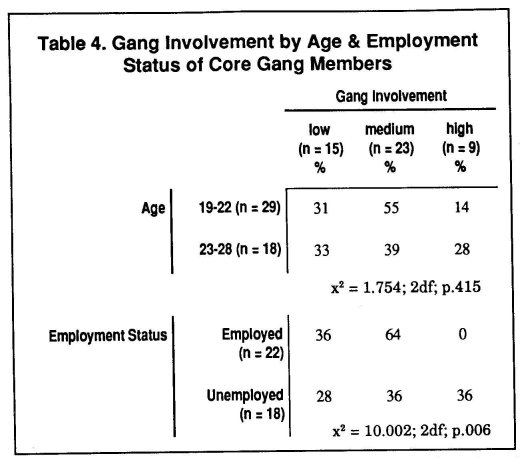

Our descriptive analysis also considered the prior offense records of the subjects. In this regard, we considered the number of gang members who had been arrested and convicted of various categories of offenses as well as the range and mean number of arrests among members. The findings for arrest and conviction are presented in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. The figures show that all of the core gang members had been arrested for a felony and virtually all had been arrested for a misdemeanor. Possession of a firearm was present in 66 percent of the cases and 40 percent of the subjects had themselves been a victim of a violent crime.

The most frequent arrests were for violent crime and drug possession, with about three-fourths of the subjects falling into each of these categories. Almost two-thirds had also been arrested for drug sales. While 96 percent of the subjects had also been convicted of a misdemeanor, only a third had been convicted of a felony, with 8 percent convicted of a violent crime, 15 percent of drug possession, and 11 percent of drug sales. It was also clear from our review of the arrest and conviction records that a substantial number of the felony arrests had been plead down to a gross misdemeanor conviction.

We also see from Tables 2 and 3 that individual core gang members have extensive records of misdemeanor and felony arrests and misdemeanor convictions. The figures show that they had an average of 18 arrests for misdemeanors and 8 arrests for felonies. They also had an average of 12 convictions of a misdemeanor. Each was on an average arrested two times for drug sales and possession.

When compared with previous research on gangs, these figures suggest that core gang members have more extensive official records of criminality than gang mem bers generally. Comparing our arrest figures to those for Klein et al.'s (1988) research, our subjects had between 10 and 19 percent more arrests. Further, all of our subjects had been arrested for a felony crime and 34 percent had been convicted. Nearly two-thirds were also arrested for drug sales, with 11 percent being convicted. These figures are at considerable variance with the self-report figures from Fagan's (1989) research that suggest a considerably lower incidence of drug trafficking by gang members, 64 percent as compared with 37 percent, respectively. This is an especially interesting observation in light of the fact that self-report studies are generally thought to elicit a higher incidence of deviant behavior than do official records. This would appear to add further support to our argument that research in the area needs to distinguish among the types of gang members in assessing the problems that they pose in drug trafficking and criminality.

Correlates of Gang Involvement

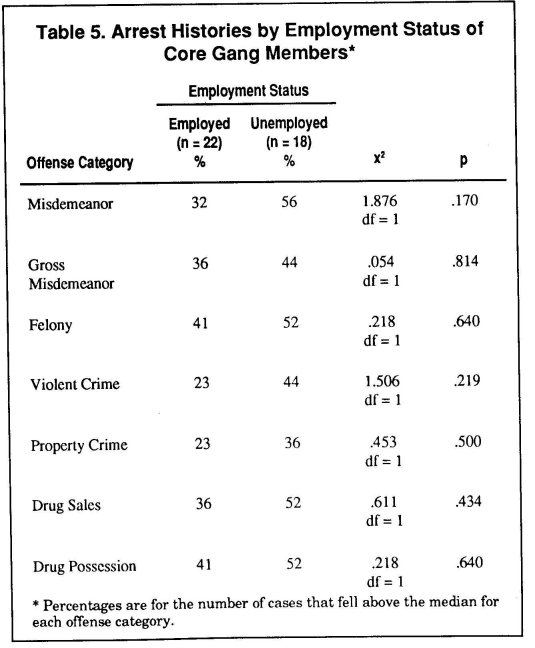

We now turn our attention to the possible determinants of the extent of core members' involvement in their gangs. It has been argued that the increased involvement of gang members in drug trafficking is related to the changing urban market structure in which certain minority males have traditionally been employed. They have as a result not aged out of the gangs, but have maintained these associations for economic survival. In an effort to explore this proposition, we analyzed the relationships between the age and employment status of our subjects and their extent of gang involvement. Our measure of gang involvement combined residence within the gang territory and having a gang tattoo. The variable was constructed by assigning a value of one to the presence of each of these factors. The scale scores range from zero to two, with zero indicating the absence of either factor, one the presence of either, and two the presence of both. Table 4 presents the findings for this part of our analysis. The figures show that only employment status was significantly related to gang involvement. None of the core members who were employed scored high in gang involvement. This would suggest that even menial jobs may serve to divert core members from the most intense level of gang membership.

Correlates of Criminality

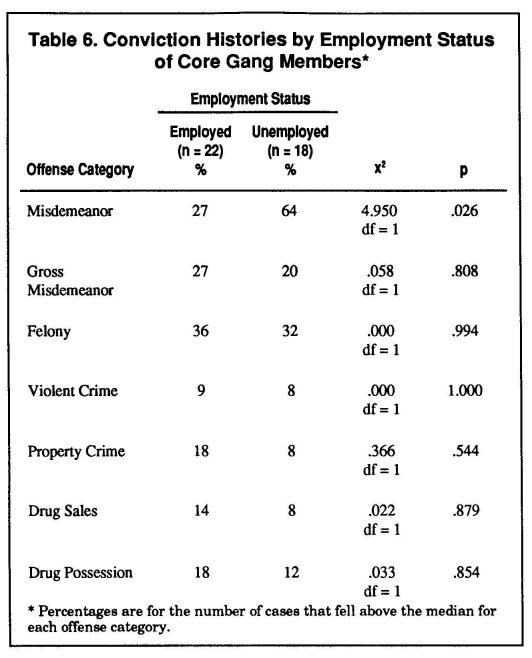

Finally, we look at the relationships of employment status and level of gang involvement to the arrest and conviction histories of core gang members.Tables 5 and 6 present the findings of the relationships of these histories to employment status. The percentages in Table 5 show that unemployed gang members were more likely to be arrested for all offense categories, with these relationships approaching statistical significance for misdemeanor offenses and violent crimes. We also find significance in the relationship between employment status and conviction for a misdemeanor, with unemployed gang members more often convicted (see Table 6). While there appear to be no other meaningful relationships between employment status and conviction for the other offense categories, it is interesting to note that the percentages slightly favor the unemployed.

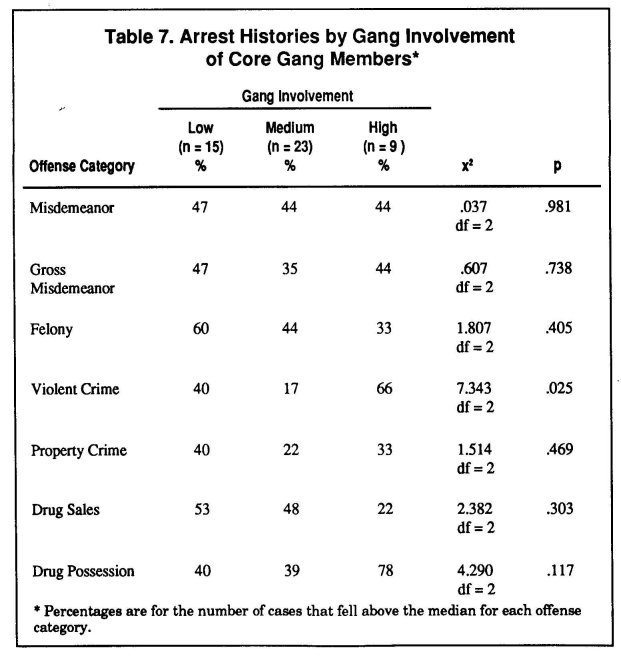

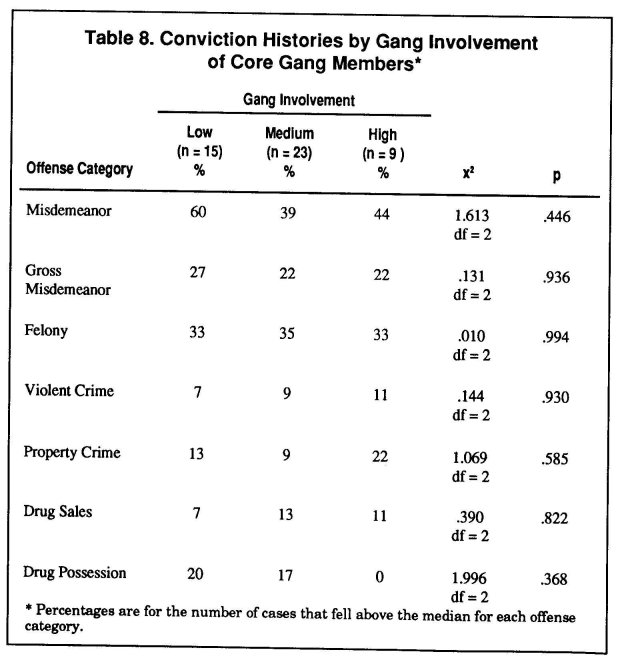

The relationships between the level of gang involvement and the arrest and conviction histories of our subjects are shown in Tables 7 and 8, respectively. Although there appear to be no significant effects of level of gang involvement on conviction for a crime, the variable is significantly related to arrest for a violent crime, and approaches significance in its relationship to arrest for drug possession. Those who were high in their extent of gang involvement were 26 to 49 percent more likely to have been arrested for a violent crime, and about twice as likely to have been arrested for possession of drugs.

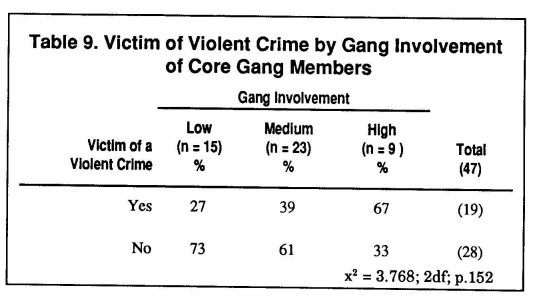

Finally, gang involvement was also found to be related to having been a victim of violence. Approaching statistical significance, the findings for this relationship are shown in Table 9. The figures show that about two-thirds of those who were highly involved with their gangs had been a victim of a violent crime. This figure is in clear contrast to the figure for those who were low in gang involvement; only a quarter of those who fell into the latter category had experienced such violence. That those who have a high degree of gang involvement are both more likely to have been arrested for a violent crime and to have been a victim of such crime is not surprising in light of the nature of interpersonal violence. Research on homicide, of example, suggests that it is often difficult to distinguish the offender from the victim prior to the deadly outcome (see Farrell and Swigert 1987). This is because such violence is usually characterized by on-going conflict in which both parties play a contributing role. That one of the parties becomes the offender and the other the victim is often the result of chance or the relative strength or agility of each.

Discussion

In Las Vegas, the drug gang problem would appear to be a product of the socio-economic conditions endemic to lower class housing projects. We have seen that all of our gangs were located in these projects and we were furthermore informed that the other gangs in the city were similarly located. The picture that emerges from our research of core gang members in these areas is one of poor, black young adult males with histories of substance abuse and extensive records of arrests for drug-related and violent crime. This picture is somewhat more dramatic than those that have emerged from some previous studies because of the more central involvement of our subjects in the life of their gangs.

It will be no revelation to those familiar with the communities in which these gangs exist that the poor and socially disorganized conditions of such neighborhoods provide few legitimate avenues for gainful employment, let alone the material success that is so highly valued in our society. The gang thus provides an alternative means of economic survival, serving as a conduit for the relatively lucrative business of drug trafficking.

We have furthermore seen that a significant correlate of gang involvement is unemployment. Even the menial jobs held by about half of the gang members in our study served to mitigate against their more extensive involvement in the gangs. None of those who were employed showed a high degree of gang involvement. Our data also suggest that unemployment is related to the accumulation of arrest records for all offense categories, especially for misdemeanors and violent crimes, and is significantly related to conviction for misdemeanor offenses. And, very importantly, from the standpoint of our central thesis, gang involvement was significantly related to arrest for a violent crime and approached significance in its relationship to arrest for drug possession.

It is apparent from these findings that core gang drug trafficking and crime are rooted in the socio-economic conditions of gang members. Effective policies directed toward the prevention and control of the drug problem must therefore address these conditions. Through the provision of employment opportunities, even unskilled jobs, we may realize some reduction in minority involvement in gang drug trafficking and related problems of crime.

Assistant Professor Carole Case and Visiting Professor Ronald A. Farrell are with the Department of Criminal Justice, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, Nev. 89159- 5009. (702) 739-3731. Theodore Snodgrass is with the Las Vegas Metropolitan Police.

References

Fagan, Jeffrey. 1989. "The Social Organization of Drug Use and Drug Dealing Among Urban Gangs." Criminology 27: 633-667.

Farrell, Ronald A. and Victoria L. Swigert. 1987. "Adjudication in Homicide: An Interpretive Analysis." Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 23: 349-369.

Hagedorn, John M. 1988. People and Folks: Gangs, Crime and the Underclass in a Rustbelt City. Chicago: Lake View Press.

Klein, Malcolm W. and Cheryl L. Maxon. 1989. "Street Gang Violence." In Marvin E. Wolfgang and Neil A. Weiner (eds.), Violent Crime, Violent Criminals. Newbury Park, CA.: Sage.

Klein, Malcolm W., Cheryl Maxon, and Lea C. Cunningham. 1988. Gang Involvement in Cocaine Rock' Trafficking. Center for Research on Crime and Social Control, Social Science Research Institute, University of Southern California.

Moore, Joan W. 1978. Home Boys. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press.

Skolnick, Jerome H., Ricky Blumenthal, and Theodore Carrel. 1990 a. Gang Organization and Migration. Unpublished Manuscript. Center for the Study of Law and Society, University of California, Berkeley.

Skolnick, Jerome H., Theodore Correl, Elizabeth Navarro, and Roger Rabb. 1990 b. "The Social Structure of Street Drug Dealing." American Journal of Police. 9:1-41.

Spergel, Irving A. 1989. "Youth Gangs: Continuity and Change." In Norval Morris and Michael Tonry (eds.), Crime and Justice: An Annual Review of Research. Vol. 12. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Footnote

1 The limitations of our data on current drug use and dealing do not allow us to address Skolnick's (1990) intriguing observation regarding the cessation of drug use by those dealing cocaine and heroin. Nor did our data allow us to explore the relationship between drug abuse and dealing. This is because our measure of drug abuse is partially based on official records of arrest and conviction, the same data that would have to be used to measure dealing. Such an analysis would, however, be useful to explore the popular view that users who are poor often became dealers in order to support their own habits.

|