CHAPTER III THE CANNABIS PROHIBITION REGIME: MARKETS, POLICIES, PATTERNS OF USE AND OF SOCIAL HANDLING

| Reports - The Global Cannabis Commission Report |

Drug Abuse

CHAPTER III THE CANNABIS PROHIBITION REGIME: MARKETS, POLICIES, PATTERNS OF USE AND OF SOCIAL HANDLING

This chapter reviews cannabis use and the cannabis market in the current circumstances of an international prohibition regime. Prohibition of an attractive substance creates illegal markets, which have consequences in terms of the contours of production, distribution and consumption. In the first half of the chapter we examine data on the prevalence of cannabis use, the prices that are charged and the revenues that are generated. The second half examines the enforcement of prohibitions; how many individuals are charged with various kinds of cannabis offenses and what are the consequences of those charges. The emphasis is on the developed world, both because more data are available and because there is evidence that use rates are substantially higher in Western Europe, North America and Australia than in most poorer countries. The emphasis of the chapter is on the effects of full prohibition. We also cover the recent phenomenon of increasing demand for cannabis treatment, as it provides an important rationale in some countries for the continuation of the complete prohibition regimes. Lastly, we briefly describe the structure of the international prohibition regime, and its resistance to change on matters concerning cannabis. Chapters 4 and 5 take up the issue of how variations in prohibition, such as decriminalization, affect the principal outcomes.

PREVALENCE

In many, but not all, regions of the world, cannabis is the most commonly used illicit drug. It is both cheap per dose and readily accessible to the general population.

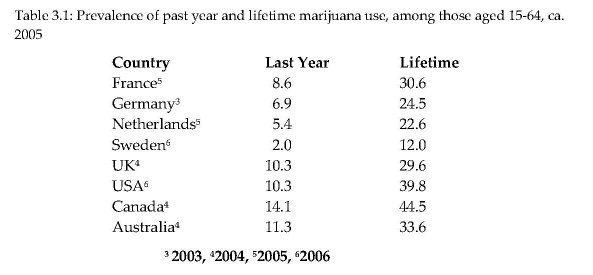

Table 3.1 presents data on cannabis prevalence for a number of countries around the world1. There is a problem of comparability, dealt with in footnotes, but the major patterns are clear. In many western nations cannabis use is a normative experience; half or more of 21 year olds born since 1970 will have tried the drug at least once. There are, however, a few western nations in which that is not true. In the Nordic region (other than Denmark), for example, the rates are much lower; a little more than one fifth (21.4%) of youths aged 20-24 have tried cannabis (Collins et al., 2004).

Rates are higher among males than females in all countries, though the rate differences vary. For example, among 15-39 year olds in Switzerland in 2002, the current consumption rate (roughly speaking, in the last twelve months) was 4.5% for females and 10.4% for males; the male rate was 2.3 times that of the female. In Canada in 2004, the female rate for those 15 and older was 10.2 %, compared to 18.2 % for males (Adlaf, Begin and Sawka, 2005); the male rate was only 1.8 times that of the female.

Data for non-western countries are much sparser,2 but suggest more variation and lower rates. For Brazil, a 2005 survey found a lifetime rate for 15-64 year olds of only 6.9% (past year rate 2.6%; UNODC, 2005). Though cannabis has a long history of use in India, often for ritual and religious purposes, a 2001 survey found a past-month rate among males of 3.0 percent; the authors of the survey believed that female use rates were very much lower, producing a modest total population rate. China is another major country in which the available data suggest that the drug is of minor importance (UNODC, 2005:277). There is no tradition of cannabis use in China, where opium was historically the drug of mass consumption. Though the rate in Colombia, an exporter to the US market, is comparable to Western levels (6% in the past year, ages 12-60) (Perez-Gomez, 2005), Mexico, which is the principal foreign producer for the US market, still has low rates: 1.7% lifetime use among adults in Mexico City (Vega et al., 2002).

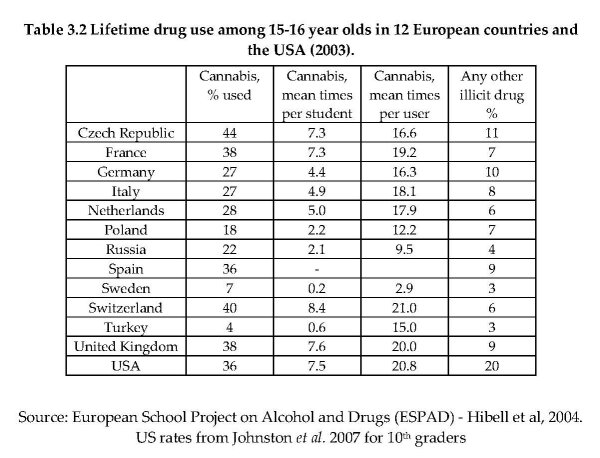

More data, and more comparable data, are available on use among adolescents as the result of a survey of students aged 15-16 that is carried out every four years in 35 European countries (the European School Project on Alcohol and Drugs survey; ESPAD). The data in Table 3.2 make three points. First, cannabis use begins early in many countries; over a third of 15-16 year olds have tried cannabis in 6 of the thirteen countries; in only three have less than one in five tried the drug. Second, there is substantial variation across countries; even among the wealthier Western European nations, Sweden’s prevalence is one-fifth those of many other nations in that group (and the rates in Norway and Finland are similar to those in Sweden). The transitional nations of Eastern Europe already show high rates of cannabis use. Third, there is less variation in the intensity of use by this age group. Almost all nations show an average number of times used of between 10 and 20.

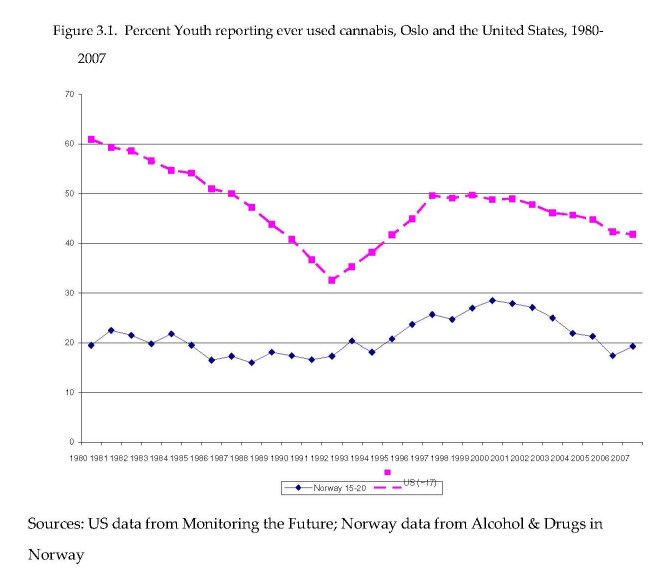

Figure 3.1 presents data on prevalence among younger users in Oslo and the United States, among the few jurisdictions for which consistent data are available over a long period of time. The age groups represented are not identical; 15-20 for Oslo and about 17-18 for the United States; but the purpose is not to compare absolute rates but rather changes over time. The two series differed in the 1980s, with the US youth rate declining sharply while that for Oslo was stable. However since the early 1990s the two series have been very parallel, rising through most of the 1990s and declining modestly since then. Similar trends for the period since 1990 can be found in less complete data in other countries such as Australia and the Netherlands.

Though cannabis initiation does not show the same strikingly short epidemics as cocaine and heroin in Western countries (see e.g. Nordt and Stohler, 2006), there have been periods of nearly explosive growth and periods of smaller but still sharp declines. For example, the prevalence of cannabis use (last twelve months among those aged 15-64) in France rose by 150 percent between 1992 and 2002 (UNODC, 2008; p.115), while in Australia the prevalence (last twelve months among those aged 14 and over) fell by nearly 50 percent in the period 1998-2007 (UNODC, 2008; p.118).

Duration and Intensity

Prevalence of use is only part of the story. As important are the length of cannabis using careers and the intensity of use during those careers.

A few studies show that a majority of users use the drug only a few times but that many do have careers of regular, if not frequent, use that extend for over ten years. For example, Perkonnig et al. (2008) studied a cohort in Munich aged 14-24 at first interview in 1995-1998. By final interview in 2005, over half the sample reported at least one incident of cannabis use. Most relevant here is that forty percent of those who reported using cannabis at their initial interview, when interviewed 10 years later, reported using the drug in the previous twelve months. The rate was, as might be expected, particularly high among those who had used five or more times at the baseline interview.

The one published long-term study of a cohort of American youth shows long periods of daily cannabis use (defined as 20 days in the previous month) for a large proportion of the sample. Kandel and Davies (1992) report on a cohort of 10th and 11th graders recruited from New York State high schools in 1971. When the respondents were re-interviewed in 1984, at age 28 or 29, over one quarter (26.2 percent) had been daily users of cannabis for at least some one-month period in their life. Even more striking, the mean duration of spells of near-daily use was over three and a half years. The much greater involvement of this sample in cannabis use may be cohort- and location-specific;3 this was a group which went through the high risk years near the peak of the counter-culture movement, and many were from New York City, which was particularly influenced by that movement.

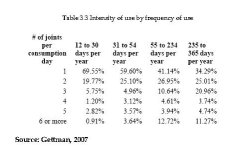

The figures on intensity of use are striking. The EMCDDA (2004) thought that it was reasonable to assume that 1 percent of the population aged 15-64 used cannabis on a daily basis. Large numbers use multiple times per day. Analysis of 2001 Australian survey data suggest that those who use daily or nearly daily consume on average about four joints per day (Pudney et al., 2006; 67). During the period 1991-1993 the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse in the United States collected detailed data on frequency of use. Of those who used most days of the year, about 40 percent used three or more joints per day on days that they used (Table 3.3).

This very skewed intensity of use distribution is similar to that typically found for alcohol; in surveys of alcohol use, the heaviest 20 percent of US drinkers account for 87-89% of total consumption (Greenfield & Rogers, 1999). Efforts to estimate the same parameters for cocaine and heroin using general population surveys are unpersuasive, since those surveys are known to omit the majority of frequent users of these drugs; indeed in the U.K., US and many other countries, no effort is made to provide estimates of the extent of dependent or heavy use of heroin from household surveys. Thus we cannot compare the skewness of use patterns for cannabis with those for cocaine or heroin.

In many surveys, relatively few of those who tried cannabis have experienced problems as a consequence. However a major survey focused on such matters, the National Comorbidity Survey in the United States, found that about 10 percent of users responded in ways which qualified them for a dependence diagnosis at some stage in their life (Anthony, Warner and Kessler, 1995), a matter we take up more fully below. Few go on to use more dangerous illicit drugs; the 1995 US National Household Survey on Drug Abuse found that only 23 percent of 26–34 year olds who had used marijuana4 at some time had also used cocaine during their lives.

Moreover, that fraction has declined in the United States for more recent birth cohorts (Golub and Johnson, 2001).

Summary

Despite its prohibition in every country apart from the Netherlands, experimentation with cannabis is a routine part of the experience of adolescence in many Western nations. Use is more common among males than females, but even among females a large proportion has tried the drug by their early adult years. A substantial fraction of those who experiment go on to use the drug frequently, and a modest share of those experience problems of dependence. The rates vary considerably across countries at the same level of economic development, probably reflecting broad cultural and social factors.

PRICE

The price of cannabis plays two roles in our analysis. On the one hand it is a measure of the effectiveness of the control regime, because prohibition aims to make the drug expensive and difficult to obtain. A modest body of research consistently demonstrates that cannabis consumption (as measured by prevalence) is responsive to price (see Grossman 2004 for a review). Higher price, ceteris paribus, will lessen prevalence and consumption, for an illicit good as for a licit one.

The second role of price is as one determinant of dealer revenues. If the price of marijuana were comparable to that of cigarettes, before taxes, then one important adverse consequence of marijuana prohibition would be eliminated, namely the corruption, violence and diversion of labor that it now generates, since the potential revenues for individual dealers would be modest. While it is strictly speaking profits rather than prices that determine the attractiveness of the trade, data on profits do not exist; moreover, in terms of the incentives for stealing drugs (a potentially major source of violence), it is their value, not profit margins, which matter.

Price data for illegal drugs are always weak, reflecting the difficulty of developing a good sampling frame and sampling strategy for illicit markets. For cannabis there is an extra problem, which is a lack of data on potency. It is plausible that more potent marijuana, precisely because it has more of the active ingredient, will be more expensive per gram, but perhaps no more expensive per unit of THC. The Dutch data on price and potency are roughly consistent with this (Pijlman et al., 2005).

A standard claim is that prohibition leads to production of more potent forms of a substance, since higher potency reduces the bulk and hence the risk associated with distribution. There is evidence for this with respect to alcohol during American Prohibition, during which the illicit market for alcohol became almost entirely spirits (Warburton, 1932). The same was true for opiates in Thailand in the 1980s (McCoy, 1991). For cannabis, any such effect has certainly been slow to manifest itself. The potency of cannabis remained quite low relative to what was technically attainable until the 1990s, twenty-five years after the emergence of major markets in a number of Western nations.

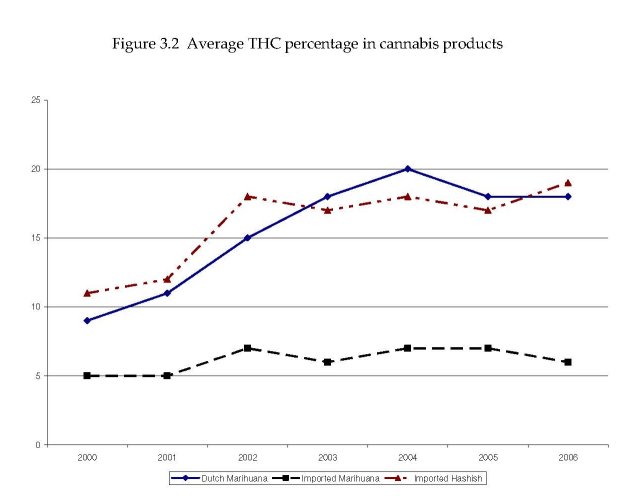

It is known that the THC content of cannabis varies substantially across countries and time periods; it may be as low as 2% or as high as 20%. A recent survey of potency in Europe (EMCDDA, 2004) found that potency had not consistently increased in recent years, and that in most countries it remained in a range of 6-8 percent (Figure 3.2). The Netherlands was an exception, with potency having risen from already high levels to figures that were never considered before, close to 20% (Niesink, Rigter and Hoek, 2005). Unfortunately the only data set that consistently records potency in connection with price is that from the Netherlands, which covers purchases in coffee shops where the drug is de facto legal.

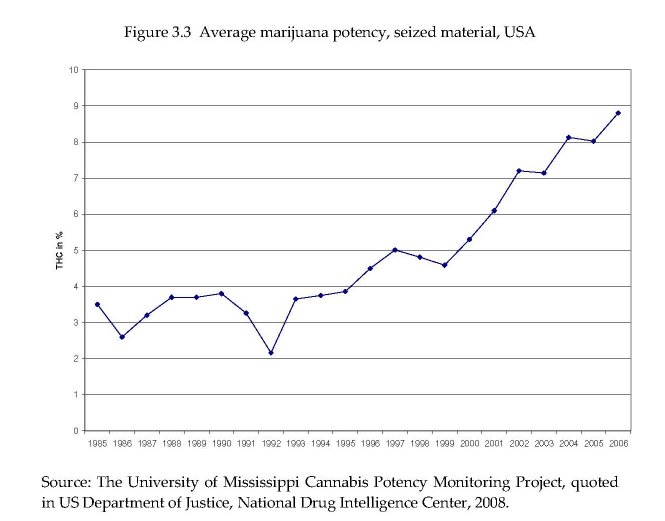

In general, there is reason to believe that average potency has increased over time in many countries. Less authoritative data are available over a longer period for the United States.5

They also show a large and sustained increase in the potency, from around 3 percent in the mid-1980s to about nine percent twenty years later (Figure 3.3). Variations in potency mean that the various price series below may not correctly measure effective price, and comparisons across countries are particularly perilous.

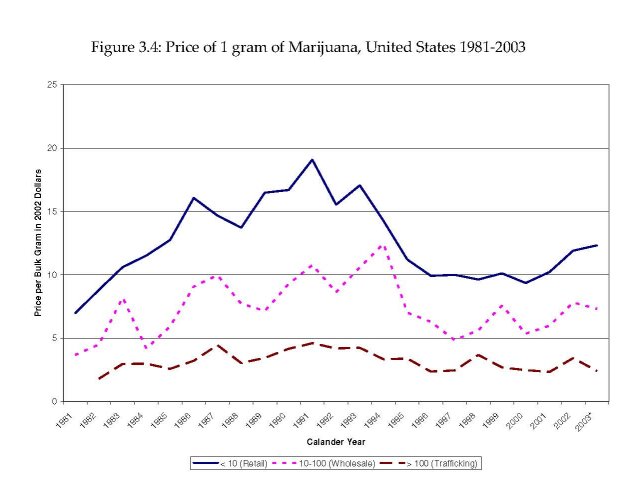

As usual, more price data are available for the US than for any other country. Figure 3.4 (from Caulkins et al., 2004) shows retail and wholesale prices (at two levels) for marijuana from 1981 to 2003.6 Taken at face value (i.e. ignoring unmeasured changes in potency), this suggests that prices rose during the 1980s, declined during the 1990s, and rose again in the first half of this decade. Caulkins (1999) has shown that this variation in prices can indeed account for most of the observed fluctuation in last-year marijuana use among high school seniors up to 1998; prevalence declined during the 1980s and rose during the 1990s. The data from the government potency monitoring study suggest that marijuana potency has been increasing sharply at least since 1990, so this may be misleading.

For other countries, cannabis price information is scarce. For example, Pudney (2004:437), in a careful analysis of cannabis use in the U.K., noted that: “The only systematic source of price information comes from the National Criminal Intelligence Service (NCIS). This goes back no further than 1988 and gives only ad hoc ranges of street prices reported by police drug squads in various locations”.

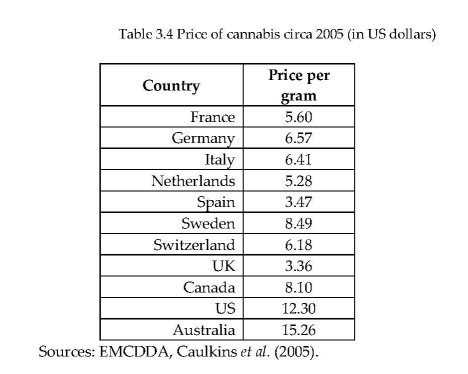

The EMCDDA published in 2005 estimates of cannabis prices for a number of its member states. The underlying data are of varying quality; some may be little more than police guesswork. Table 3.4 presents these figures, along with data for the US, Canada and Australia.

The EMCDDA (2007) reported that, adjusted for inflation, cannabis prices had fallen in all but one of the countries reporting data. One of the few other analyses of prices over time is that of Clements (2004), using data for Australia; he found that over the 1990s, the real price fell by 40 percent.

It is useful to compare the price of cannabis to that of other sources of intoxication. In the United States a standard drink (e.g. a 12 oz. can of inexpensive beer) costs about $1, at package store (off-sale) prices. For the average person, a moderate level of intoxication would require about three drinks. If a joint contains 0.4 grams, at a price of $12 per gram, it only costs $5 to get high. The comparison is of course a very rough one, but it indicates that prohibition still leaves cannabis competitive with a taxed legal commodity as a source of intoxication.

QUANTITIES AND EXPENDITURES

A nation’s cannabis problem is not measured merely by the numbers of users but also by the quantity consumed and the amount of money spent. Most harms experienced by users are an increasing function of the quantity consumed; if each gram of cannabis used increases the risk of a driving accident, then it is useful to estimate total quantity consumed. Expenditures represent the size of the black market available for bribes to officials, and the temptations to youth to divert labor from legitimate activities. Unfortunately, there are few estimates of quantities and expenditures.

The best documented estimate is for the U.K., developed by Pudney et al. (2006). Like all such estimates, it relies on self-reports of use and intensity of use and must therefore be regarded as a lower-bound figure. Even with alcohol it has been impossible with self-report population surveys to replicate total consumption and expenditure estimates based on tax records; developing an estimate as high as two-thirds of the known figure has been about the best any scholar has been able to attain (Greenfield et al., forthcoming). Pudney et al. estimate that in 2003/4 total cannabis consumption in the United Kingdom was about 400 tons and expenditures totalled £1 billion; this compared to £40.8 billion for alcohol and £15.6 billion for tobacco in 2004 (Harris, 2005:246).

71

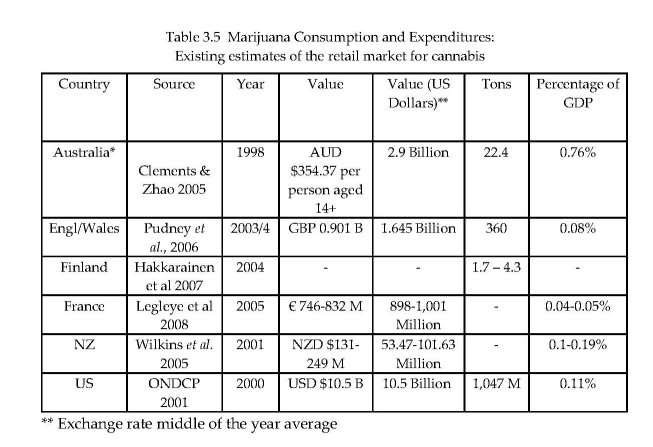

Table 3.5 presents the few national estimates of cannabis consumption and expenditures per capita for recent years, along with expenditures per user and as a share of GDP. If the underlying surveys are as accurate as those for alcohol, which seems optimistic, the quantity estimates should be increased by 50% to provide a more realistic figure. Nonetheless, it remains the case that cannabis expenditures are small compared to those for alcohol and tobacco.

Table 3.5 Marijuana Consumption and Expenditures:

Table 3.5 Marijuana Consumption and Expenditures:

THE MARKETS FOR CANNABIS

Estimates Of Cannabis Production

Cannabis differs from the other major natural base illegal drugs, cocaine and heroin, in that it is produced in many of the major wealthy consumer countries. One hundred and thirty-four countries reported cannabis production in their territory, according to the UNODC (2007). Most produce only for domestic consumption. This makes it particularly difficult to estimate total production of cannabis (Leggett and Pietschmann, 2008), since it is not produced in large fields in concentrated areas of a few countries; the latter characteristic has simplified the task of estimating global opium and coca production7. Leggett and Pietschmann (2008) discuss the official global estimates of 40,000 tons with appropriate caution. It is hard to reconcile that figure with an estimated consumer population of 160 million. If we use 100 grams as a relatively generous estimate of the per user annual consumption; this yields a total quantity less than half as big (160 million x 1/10 kg = 16,000 metric tones). Seizures in 2006 amounted to about 7,000 tons, according to the 2008 World Drug Report; seizures were concentrated in Mexico and the United States.

Not much is known about markets for cannabis, but at least three characteristics come through from the existing literature in a number of countries:

1. Very large numbers of persons are involved in distributing the drug, and large numbers in growing it. Gettman (2007), analyzing data from the US National Survey on Drug Use and Health, reports that almost two percent of respondents reported that they had sold an illegal drug in the previous twelve months; among respondents aged 18-24, the figure is six percent. This covers all drugs, not just cannabis, but it is likely that the vast majority are involved in cannabis selling. A forthcoming paper by Bouchard, Alain and Nguyen (under review) reports data from a school in a part of Quebec province that is known to have high involvement in cannabis production. Bouchard et al. found that 15 percent of youth reported being involved in growing cannabis.

2. Imports from the developing world account for a modest and decreasing share of the rich world’s consumption. The Netherlands estimates that the domestic production from approximately 18,000 “cannabis farms” was between 130 and 300 tons of cannabis in the early part of this decade (van der Heiden, 2007). This was far more than might be consumed by Dutch users and the coffee shop visitors (less than 80 tons). Some of this is exported to other Western European nations. Bouchard (2008) estimates that production in the province of Quebec in 2004 totalled 300 tons, of which less than one-third was consumed in the province. Most of the rest was presumably shipped across the land border with the United States.

As a corollary, the length of the distribution chain for cannabis is much smaller than those for cocaine or heroin. For example, it is quite plausible that heroin passes through an average of ten transactions between the poppy farmer and the final customer (Paoli, Greenfield and Reuter, in press). Although there are occasional border seizures of multi-ton shipments, it is clear that much of the cannabis is delivered through chains with no more than two or three links between the producer (a local grower) and the end user.

3. Violence is not commonly found in cannabis markets. This is mostly an inference from the absence of reports rather than any positive information that disputes between market participants are resolved amicably and that competition for territory is lacking. The United States always figures prominently in accounts of violence in drug markets. Even though cannabis involves many more producers, sellers and dealers than cocaine or heroin, there are only occasional references to homicides or other kinds of violence in the market. A recent investigative report of the grey market in “medical marijuana” in California remarked on seeing “thousands of Tibetan prayer flags” along the way, which served to “identify their owners with serenity and the conscious path, rather than with the sinister world of urban dope dealers, who flaunt muscles and guns” (Samuels, 2008). Gamella and Jimenez Rodrigo (2008) report some incidents of violence in the upper levels of the import trade in Europe, but also comment that the violence seems substantially less than that involved in markets for cocaine or heroin.

Cannabis, more than other illegal drugs, seems to be acquired within social networks, with purely market transactions as a secondary source of acquisition. Caulkins and Pacula (2006) analyzed the National Survey on Drug Use and Health and found that most users reported that they acquired their marijuana from a friend (89%) and for free (58%). There certainly are street markets of the conventional variety, but this is not, at least in the United States, the principal mode of acquiring the drug. Caulkins and Pacula estimate that in 2001 there were about 400 million purchases, each involving an average of about 7 joints. This estimate is broadly consistent with 2 million sellers, most of them very much part-time dealers, who make 200 sales per annum and have gross revenues of about $5,000 each. The fact that the market is so imbedded in social networks may be an important factor in explaining the lack of violence.

Production for own use is a substantial source of cannabis in some countries. For example, Atha et al. (1999) estimated that 30 percent of cannabis consumed in the U.K. was home grown, while in New Zealand a majority of respondents reported at least some of what they consumed was home grown (Wilkins et al., 2002). Analysis of US survey data also shows that much is given away; Caulkins and Pacula (2006) found that 58 percent of users reported that the marijuana acquired most recently was given to them free.8 In Spain, Gamella and Jimenez Rodriguez (2004) report a number of indicators of increasing home cultivation since 1992, in response to a change in Spanish law that allowed the police to make a criminal arrest for transporting cannabis.

Unsurprisingly, young people in many Western countries report that the drug is readily available to them. Even in the ESPAD survey of 15-16 year olds, as many as 80% of respondents in some European countries report that they can obtain cannabis. In the United States, the percentage of high school seniors reporting that marijuana is available or readily available has been over 80 percent for the last thirty years.

Summary

Though cannabis is very much more expensive than it would be if it could be legally produced and remained untaxed, the drug is readily available in many Western societies at a cost that allows cannabis to compete with alcohol as a source of intoxication. This is partly explained by the fact that it can so readily be produced within rich countries in small quantities that are often traded within social networks.

CANNABIS POLICIES

With few exceptions, most countries are signatories to the international conventions (see Chapter 6) requiring the prohibition of cannabis production, sale and possession, with criminal penalties. Famously, the Dutch do not enforce the prohibition in certain circumstances, but the law on the books does specify possible criminal penalties even for possession. Various other jurisdictions, as discussed in Chapter 4, have decriminalized possession to a greater or lesser extent by way of changes to the law, but all retain a prohibition on the commercial production and sale of cannabis.

With these interesting exceptions applying to a tiny fraction of the population of the developed world (analyzed in detail in Chapters 4 and 5), the important variation in the nature of national cannabis use control is determined by how the law is administered. It is a tale about practical law enforcement, pure and simple.

We give no discussion of source country control programs, a staple of efforts to reduce cocaine and heroin consumption. Although Mexico and Morocco are important suppliers of cannabis products to the US and European markets respectively, they account for a modest share of the total market, and there is little faith that eradication of their production would have much impact on its availability. Another difference is that seizures of cannabis, although they constitute two-thirds of all drug seizures and an even substantial as a share of total cannabis consumption (perhaps as much as one third), get little attention as a policy tool.

Arrest For Use Or Possession

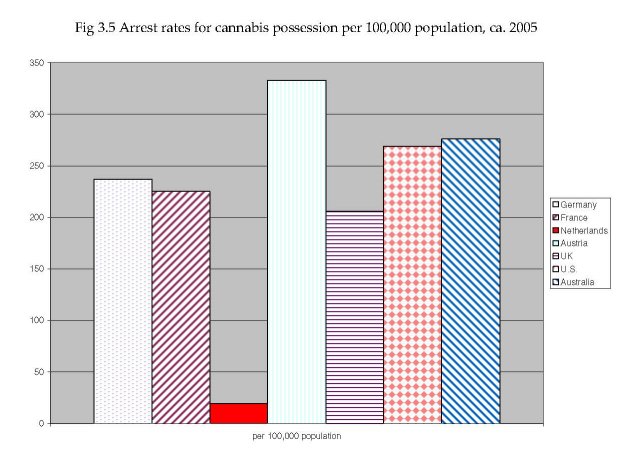

Cannabis arrests account for the majority of drug law arrests in most Western countries. For example, in Australia they accounted for about three quarters of all drug arrests in the period 1995-2000, while in Germany in 2005 they accounted for 60 percent of the total; cannabis possession and use offenses alone were 45% of the total. Figure 3.5 presents some data on cannabis arrest rates per capita in a number of Western nations around 2005. Switzerland stands out in this respect with over 600 arrests per hundred thousand population. The US has a rate of about 300 per hundred thousand, not much more than various other Western European nations or Australia. These arrest figures are a mix of formal arrests and citations. In some countries even a citation will be recorded as an arrest, in others that is not the case. In some countries the rates include only arrests for which the cannabis offense is the most serious offense of arrest; in others it includes all offenses in which cannabis is included.

In many countries, cannabis arrests have risen sharply since the mid-1990s. For example in Switzerland cannabis arrests totaled about 17,000 in 1997 (15,500 for consumption) and had risen to over 29,000 (26,000 for consumption) by 2002; that figure has since declined slightly. In the United States there was a massive increase in cannabis possession arrests starting in 1991. The number more than doubled in three years (226,000 in 1991 to 505,000 in 1995) and has continued to rise sharply, so that by 2006 it was estimated to be over 735,000, a 45 percent increase in 11 years. Australia is unusual in that it has seen a decline of one-third over the period 1995- 2005.

Arrest rates per capita of course vary a great deal by age and sex and, where the data are available, by race. In Australia, males are arrested four times as frequently as females. In Switzerland the ratio is over five to one. These are much higher than the male/female ratios of prevalence of use cited earlier, but they have not been adjusted for intensity of use, so that the risk per use occasion may not differ much between the sexes.

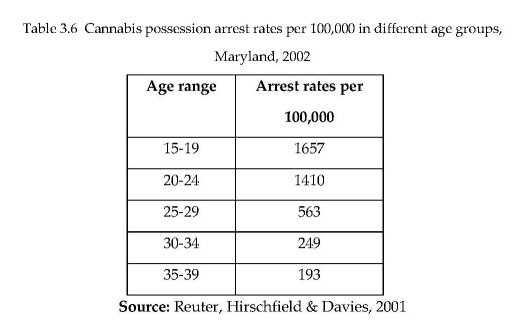

The age gradient can be very steep. Table 3.6 shows the rates for cannabis possession arrests in five-year age groups in the State of Maryland, USA, in 2002. The rate among 15-19 year olds is almost nine times the rate among those aged 35-39. The same pattern can be seen in data from Switzerland. In 2002 the arrest rate for cannabis possession for males aged 18-24 was about 4,000 per 100,000, twice the rate for those aged 25-34, and over six times the rate (600) for those aged 35-49.

Data by minority status are hard to find outside the United States. In the state of Maryland in the period 1980-1997, the ratio of rates for whites and African-Americans have varied substantially; the rates were about equal in the early 1990s, but by 1997 the rates for African-American residents were twice as high as for white residents.

To some extent the arrest rate reflects differences in cannabis use prevalence by group. Males have higher use rates than females and use is most common amongst those aged roughly 16-24. However, when one adjusts for differences in prevalence by age, it still appears that younger users are at substantially higher risk of being arrested than are their older counterparts. This may reflect the relative indiscretion of youthful users and the fact that they spend more time in exposed settings and have less opportunity for use in private places than older adults. Studies of arrests for smoking marijuana in a public place in New York City, where the arrests fall disproportionately on blacks and Hispanics (Golub et al. 2007), found that observing “etiquette” about not smoking in public, etc. made a difference in the likelihood of arrest in poor black neighbourhoods but not elsewhere (Johnson et al., 2007).

Punishment For Use Or Possession

Arrest of course is just the first step in the criminal justice process. It is just as important to have data on the steps and punishments that follow arrest. In general the data show that, for cannabis possession or use, punishments other than fines are rare. For example, Lenton, Ferrante and Loh (1996) report that in Western Australia in 1993, well before it decriminalized the offence of cannabis possession, 94% of arrestes (including those charged with possession of paraphernalia) received a simple fine and only 0.3% received a custodial sentence. Weatherburn and Jones (2001) report that in the Australian state of New South Wales in 1999, just 1.2 percent of those convicted of cannabis possession or use were sentenced to prison, and such punishments typically came when the cannabis use offense happened in conjunction with other offenses and/or the offender had an extensive criminal record. In Switzerland, the vast majority of cannabis possession offences result in a fine of less than 250 Swiss Francs (about $250 in 2008), and are not recorded as convictions in aggregate statistics.

In the United States, data on dispositions of cannabis arrests are hard to find precisely because they are prosecuted as misdemeanors and most data systems are set up to track the disposition of more serious offenses (felonies). Golub, Johnson and Dunlap (2006) report that in New York City marijuana possession arrestees “face a day in jail pending arraignment (if detained) ... and the remote possibility of a few additional days in jail if convicted” (p. 133). Reuter, Hirschfield and Davies (2001) studied the disposition of arrests for simple possession of marijuana in three large counties in one state (Maryland) that has not decriminalized drug use but is generally seen as liberal in its policies. The study found that almost no arrestee received a jail term as a sentence but that one in three of all arrestees spent at least one night in jail and that one out of ten spent at least ten nights in jail.

There are, however, more subtle effects that should not be ignored. Imposing a criminal conviction can create barriers to employment in some occupations and organizations and lead to loss of other privileges. An ironic example is that a criminal conviction may lead to rejection of an application for a US visa; this effect of criminal conviction was one factor in the Western Australian parliament moving minor cannabis offences to a non-criminal category.

Risks To Dealers

In contrast to users, those arrested for smuggling, growing or dealing can face serious punishment. Even the Netherlands, with its tolerant policy toward cannabis consumption, is aggressive in its pursuit of growers and traffickers. Korf (2008) reports that the number of prosecutions for cannabis growing rose from 4,324 in 2000 to 6,156 in 2003 (about 4 per 10,000 population). Switzerland, another country with a well-established reputation for liberal drug policies, also prosecutes relatively large numbers for marijuana dealing or growing, with nearly 4,000 individuals in 2003, or 8 per 10,000 populaton. On a per capita basis these figures may be close to that for the United States.9

In the US, the penalties for dealing can be very severe indeed; Schlosser (1994) discusses some egregious cases, in which an individual engaged in marijuana growing received a sentence of over 20 years. In the federal courts, which generally only handle cases involving large quantities of the drug, nearly 6,000 individuals were convicted of cannabis offenses in 2007, mostly for selling and importing; 97 percent pled guilty, and the average sentence length was just over three years (Sourcebook of Criminal Justice Statistics, 2007, Table 5.25.2007). Interestingly, 41 percent of those sentenced were foreign born, compared to just under 30 percent for federal drug offenders in general (Table 5.39.2007). This suggests how much the high level trade involves natives of other countries, even if they may be more likely to be caught than US citizens.

HOW TOUGH IS ENFORCEMENT OR HOW RISKY IS USE?

Cannabis is a mass market drug. Very large numbers of arrests may still mean that any individual user is at quite low risk of being apprehended. For example, Weatherburn and Jones (2001) estimated that in New South Wales, Australia, with 7,820 arrests for cannabis in 1999 (approximately 122 per hundred thousand population), only one in approximately 100 marijuana users appeared in court charged with this offense, and that fewer than one in 10,000 of a prison-eligible age were sent to jail for the offense.10

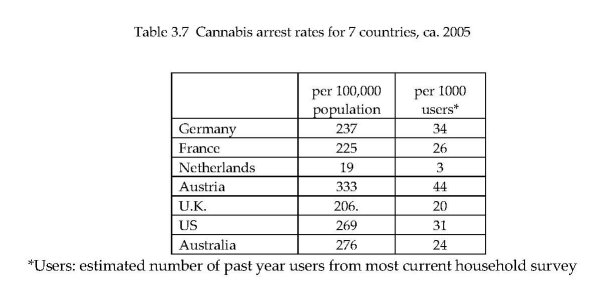

Table 3.7 provides rough estimates of user risk of arrest annually for eight nations around 2005. In no country was the rate more than 5 percent. Indeed, the narrow range for all these countries, except the Netherlands with its official tolerance, is surprising given the formal differences between countries where police have discretion about whether to make an arrest and others, such as Germany, in which the police are required to respond to any violation they observe.

Another way of performing the risk calculation is to estimate the probability that any given occasion of cannabis use results in arrest. The intensity of cannabis use is, as already noted, quite variable over the current user population. However a substantial fraction or users use it more than once per week. For example, in Finland Hakkarainen et al. (forthcoming) estimated that about five percent of users consumed daily, and an additional 15 percent consumed weekly but less frequently than daily. The total of 106,000 users consumed about 3 tons (averaging the high and low estimates), with each joint containing an average of 0.4 grams of cannabis; this yields 7.5 million joints or about 75 joints per user per year. If each joint represented a separate use event, the probability of detection for any given joint then becomes vanishingly small, less than one in one thousand.

The calculation is different, and even more speculative, if we inquire as to what is the risk of a user getting caught in the course of a cannabis use career. We suggest a simple approach. Estimate the probability of arrest per consumption episode and then assign each user the average number of consumption episodes per annum over the average number of years. If there is a one in 3,000 chance of being arrested for any one episode and the average career involves 300 use episodes, then a user has a one in ten chance of being arrested at some stage. A more sophisticated version of this categorizes users by intensity of use and calculates the probability for each category.

The reason for conducting this “career risk” calculation is that the decision made by a user can be modelled on the assumption that the user is either myopic or far-sighted. This has been the center of the contentious debate about “rational addiction”, the model that Gary Becker and Kevin Murphy (1988) developed for the study of the demand for addictive substances. In our adaptation of the model, the myopic user considers only the risk of being arrested for his first use; the far-sighted (perhaps “rational”) user takes into account the risk over his expected lifetime of use. Given that user careers begin in early teenage years in many countries, the myopic model is more appealing, but it is worth knowing what is the likelihood of arrest in the course of a user’s entire career.

The calculation here is highly speculative because there is so much heterogeneity both in arrest risks and in number of episodes. However using crude averages for the United States, we calculate that a user has a 30 percent chance of being arrested in the course of a career that is on average 10 years long. The calculation should be refined before being taken seriously.

What Are The Consequences Of Tougher Enforcement?

On its face, enforcement of cannabis prohibition seems unsuccessful. Certainly it has not succeeded in preventing cannabis use becoming a routine behavior for large percentage of young people in many Western countries. Although the actual punishments imposed are quite modest, it is reasonable to ask whether the large numbers of arrests have a deterrent effect.

This turns out to be a difficult question to answer for methodological reasons. The relevant measure of intensity of enforcement is the probability of arrest conditional on use; however that means that the percentage of the population using cannabis appears in the denominator on the right hand side of the equation, as well as in the dependent variable, creating potential bias.11 Cross-national studies are unlikely to be persuasive, since there are many other factors that affect prevalence which cannot readily be specified. Within-country studies have more plausibility, but they require a measure of cannabis use at the sub-national level to match with enforcement intensity. There are few countries with a federal structure that allow such analysis.

Pacula, Chiriqui and King (2003) use marijuana arrest rates per capita and marijuana arrests as a share of all police arrests in modeling differences in prevalence of use among youth across US states. They find that neither arrests variable is significant, replicating the results of a similar model, with different data, by Farrelly et al. (1999). The literature is thin, but provides no evidence that higher rates of arrest are associated with lower rates of cannabis use.

TREATMENT-SEEKING BY CANNABIS USERS

A relatively new phenomenon is large-scale treatment-seeking by cannabis users. In many Western countries there has been a rapid and sustained increase in the number of treatment admissions for which cannabis is identified as the principal drug of abuse. For a recent review of the treatment literature, see Bergmark (2008), who finds evidence that many modalities have substantial beneficial effects on cannabis use and related problems, but that no modality seems superior to others. Our purpose here is to document the rise in the flow of clients and to assess what drives it.

The EMCDDA (2007), on the basis of data from 21 of its 25 member countries, estimated that cannabis was the primary drug of abuse for 20 percent of all treatment cases in EU countries in the most recent year for which data were available. Even more strikingly, in 2005 the share of all first admissions to treatment accounted for by cannabis was 29%. The total number had trebled between 1999 and 2005. Cannabis admissions were exceeded only by those for heroin. The rates and rates of increase varied considerably across countries within Europe; for France cannabis admissions were 30% of all treatment admissions, whereas for some other EU countries the figure was less than five percent.12

In the United States the increase had begun earlier but was similarly startling in magnitude, given that overall cannabis prevalence had remained quite stable since 1988. Whereas in 1992 cannabis was the primary drug of abuse for 10.2 percent of all admissions that percentage had risen to 15.8 percent by 2005; the total number of cannabis admissions was 171,000 in 1992 and 292,000 in 2005. In the latter year, cannabis was the most frequently cited primary drug of abuse among admissions. A study of Ontario treatment admissions in 2000 found that cannabis was the drug most frequently cited as the primary cause for admission (Urbanoski, Strike and Rush, 2005). A later study of admissions to publicly supported treatment programs between 2001 and 2004 found that about one quarter of all admissions reported cannabis problems (Rush and Urbanoski, 2005).

Even with this increase, the share of cannabis users in treatment programs at any one time is very small. For example, the EMCDDA estimates that past year users totaled 23 million in 2004; treatment admissions totalled about 65,000, barely three-tenths of one percent of the total. The figure looks very different if one makes the assumption that all those seeking treatment are frequent users (which is questionable to the extent that some are referrals from the criminal justice system).13 The EMCDDA estimate of daily users in the European Union is 3 million. If all those in treatment were daily users, this would suggest that about 2 percent of daily users were receiving treatment. This is well below the corresponding figure for heroin, which is as high as 50 percent in some EU countries.

Another way of looking at the figures is to compare the annual numbers of new daily users and of new treatment admissions. If the system were in steady state, which it is not, this would provide a rough estimate of the probability that a daily user receives at least one episode of treatment. Unfortunately there are no systematic estimates of the number of new daily users, so one can make only rough back-of-the-envelope calculations. If time spent in the state of being a daily user is 20 years, then there might be 150,000 new daily users in Europe; the new treatment admission figure of 40,000 would then look very high. We offer this merely as a very speculative basis for suggesting that in the future treatment may become a common experience for those with cannabis dependence problems.

What has driven this increase in treatment seeking? Certainly many factors are potentially involved and they probably play a different role in different countries:

Prevalence. In some countries treatment demand may simply track increased use. That clearly is implausible for countries such as the United Kingdom, the Netherlands or the United States, where total population prevalence is either flat or declining.

Intensity of use may have increased, as measured for instance by the share of all past-year users who used daily, indicating that a higher fraction of users have problems. In Europe, only recently have national surveys included detailed data about frequency of use, so that in general there is not trend data for this part of the problem. For the United States, the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (covering the years 2002-2004) for the age group 18-25 found that 4.3% were daily users of marijuana in the previous year, constituting 15% of past year users in that age group.

Criminal justice referrals. For the United States, the rapid rise in arrests for marijuana possession is certainly a factor. One method of minimizing the chance of a serious sanction for such an arrest is to be able to inform the judge that the defendant is in a drug-treatment program. A high fraction of those classified as marijuana treatment admissions in 2005 (58 percent) were listed as criminal justice referrals, much higher than for either cocaine or heroin (SAMHSA, 2007). However, given that there are almost no arrests for cannabis possession in the Netherlands, that is unlikely to be a factor in the increase in that country. There may also be forms of “soft coercion” from schools and teachers that also play an increasing role.

Supply of treatment places. Only recently have treatment providers begun to offer specialized services for cannabis users. This may be an independent influence; treatment providers may be responding to the decline in demand for services specific to other drugs, in countries such as the Netherlands with an ageing and slowly declining population of dependent heroin users.

Awareness of potential harms of frequent cannabis use. There has been increasing media coverage of the possibility that cannabis use might lead to schizophrenia or psychosis. This may have caused more users with careers of frequent use to seek to stop and, in face of problems in doing so, to seek therapeutic help to accomplish that goal.

The list can be easily lengthened. For example, higher potency might cause more problems, improved record-keeping might mean that a higher percentage of actual cases are captured in statistics, while declining age of first use might lead to earlier identification of problems by users. There may have been shifts in the settings in which the drug is consumed that have increased harms. No doubt still others will emerge with further research.

Under a system of prohibition that has not changed much in the past decade, there has been a sudden surge in the numbers seeking help in dealing with problems associated with cannabis use. The increase has been observed in many nations with long histories of cannabis use. The numbers are now large enough in many countries to suggest that cannabis use is a significant problem for at least a modest proportion of all users and a substantial proportion of heavy users. For our purposes the treatment seeking increase is a reminder that the problems associated with a drug are determined by many factors and are not a timeless constant, a point that is well understood in the alcohol policy field. For example, changes in patterns of drinking can have profound effects on the adverse consequences of a given per capita alcohol consumption. The same may be true for cannabis, and the appropriateness of a particular policy will depend on that.

CANNABIS IN THE INTERNATIONAL PROHIBITION REGIME

As noted, almost all countries are signatories to the 1961 and 1988 drug control Conventions, and are required under these conventions to criminalize production, distribution, use or possession of cannabis. Cannabis was brought into the emerging international drug control system in 1925, at the instance of the Egyptian delegate to the Second Opium Conference, but only with respect to medical preparations from the resin (Bruun et al., 1975:183). Cannabis preparations had had wide medical use at the end of the 19th century (Fankhauser, 2008), and in 1952 1000 kg. per year was still used for this purpose (Bruun et al., 1975: 201). Primarily under urging from the US (Bruun et al., 1975: 195-203; Edwards, 2005:153), cannabis was included in the strictest prohibition regime category in the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs. This decision was premised on a conclusion that cannabis had no medical value; it was agreed that in the new treaty “it should ... be made clear that the use of cannabis should be prohibited for all purposes medical and nonmedical alike” (10th Session of the CND, quoted in Bruun et al., 1975:199). The fundamental decisions on the status of cannabis in the international regime were thus taken prior to the much wider modern experience with its nonmedical use. The effect of the 1961 Convention was broadened by the provision in the 1988 Convention requiring the production, distribution, possession or purchase of cannabis to be treated “as criminal offenses under [each country’s] domestic law”.

The Organs Of The International Regime

There are three main international bodies with responsibility under the drug control conventions (Room & Paglia, 1999). The Commission on Narcotic Drugs, with 53 nations elected as members by the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) of the United Nations, meets annually as the policy-making body. The International Narcotics Control Board (INCB), composed of 13 persons chosen as experts, has a dual role as the manager of the international supply of plant-derived medicines, particularly opiates, and as the watch-dog of the prohibition system for drugs covered by the treaties. The UN Office on Drugs and Crime serves as the secretariat for the system, with a broad international program of work. A fourth international body, the World Health Organization, also has a technical role in evaluating drugs and recommending on how they should be classified under the system.

The Place Of Cannabis In The System

Cannabis is by far the most commonly used substance subject to the system’s prohibitions, but it has never been central to the concerns and activities of the system. The discussions of production and trafficking of cannabis in the UNODC’s World Drug Report 2000, for instance, lacked the specificity of the discussions of opium and coca trafficking. “Available cultivation and production estimates are not sufficient to determine whether production at the global level has increased or decreased in recent years”, the Report remarks (UNODC, 2000:32). The Report went on to note that cannabis seizures rose in the early 1990s, but “have not increased since the mid-1990s”, but added that it is difficult to judge if this reflects “a real stabilization in global production and trafficking” or shifts in law enforcement priorities. By 2008, a substantial effort had been made to make the global picture for cannabis more concrete. Discussion of the global cannabis situation occupied about one-fifth of the space devoted to specific drug classes (UNODC, 2008:37-169). But this allocation might be compared with the Report’s estimate that 65% of global seizures, and 67% of the “doses” of drugs seized, were of cannabis, and that the estimated global rates of drug use were 3.9% for cannabis, 0.6% for amphetamines, 0.4% for cocaine, and 0.4% for opiates (UNODC, 2008:26, 31).

Indications can be found in all parts of the system of the marginality of cannabis in the system’s concerns, at least until recently. The Bulletin on Narcotics is a research journal published by the UNODC and its predecessors since 1949 (http://www.unodc.org/unodc/data-and-analysis/bulletin/index.html). Of the 191 articles published in the journal between 1986 and 2005 (the date of the most recent issue), only 9 were on cannabis, 7 of which were in an issue devoted to cannabis in 1994.14 At its annual sessions, the Commission on Narcotic Drugs passes a series of resolutions, often after heated debate in drafting committees (Room, 2005), and also recommends resolutions to be passed by ECOSOC. Of the 132 CND resolutions passed in the period 1997-2008 (http://www.unodc.org/unodc/commissions/CND/07- reports.html), 4 concerned cannabis (3 of them in 2008); of the 51 resolutions recommended to the ECOSOC, one concerned cannabis. A reading of the annual report for 2007 of the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB, 2008) conveys, on the one hand, the ubiquity of cannabis growing and trafficking as the Board reports on the situation region by region, and, on the other hand, the marginality of cannabis to the system’s central concerns. Thus none of the report’s 48 recommendations is specifically concerned with cannabis.

The International System And National And Local Laws

In its self-conscious role as the “guardian of the conventions” (Bewley-Taylor & Trace, 2006), the INCB periodically mounts the ramparts on cannabis in defense of the system, for instance by issuing an admonitory press release (UNIS, 2008) in response to press reports of experiments with computerized vending machines by California dispensaries for medical cannabis to be used in accordance with a doctor’s letter. A prominent feature of the international drug control system, in fact, is the extensiveness and detail of its concerns with domestic matters in nations which are parties to the treaties. It was a common experience for national delegations to return from international drug treaty conferences with the news that amendment of domestic legislation would be required by the new treaty.

The level of control over domestic decisions to which the system aspires exceeds, for instance, the level of ambition of the European Union to control national arrangements in the same areas (e.g. concerning the Dutch “coffee shops” for cannabis), or the power of national governments in federal states to control state or provincial matters (e.g. concerning medical marijuana availability in California and other US states).

In addition to mandating controls on markets in psychoactive substances, the conventions require criminalization of the drug user, if and when the user is in possession of substances that have not been legally obtained. This is an unusually strong requirement even in the context of national laws on contraband commodities, let alone as a requirement of parties to an international treaty; there was no such provision, for instance, in the US alcohol Prohibition laws. The 1961 Convention includes specific provisions that possession of cannabis and other substances controlled by the Convention without legal authority shall not be permitted, and that, where constitutionally allowed, it shall be a punishable offence. As noted, the 1988 Convention adds the requirement that possession must be made a criminal offence.

Freezing Up: The System And Dronabinol

As noted, the World Health Organization (WHO) plays a technical role under both the 1961 and 1971 Conventions in recommending whether particular substances should be scheduled under either of the conventions, and in which Schedule of the conventions they should be placed. These recommendations are made by an Expert Committee on Drug Dependence, which is now reconstituted for a meeting every two years.

However, the international control system is increasingly inclined to disregard the scientific advice it receives from the WHO. Perhaps the most dramatic instance of this is the turning back by the CND in 2007 of a recommendation for a rescheduling of dronabinol (^-9 tetrahydrocannabinol, THC), the principal psychoactive constituent of cannabis, under the 1971 Convention on Psychoactive Substances. Dronabinol is prescribed particularly in the USA under the brand name Marinol as an appetite stimulant, primarily for AIDS and chemotherapy patients. While the plant cannabis and its natural products are included in the 1961 Convention among the substances which are considered the most dangerous and without any therapeutic usefulness (Schedules I & IV) , dronabinol was listed under Schedule I of the 1971 Convention (the most restrictive schedule) at the time of that Convention’s adoption. The 1989 WHO Expert Committee on Drug Dependence recommended that dronabinol be transferred to Schedule II of the 1971 Convention. The CND initially rejected this, but after a reconsideration by the next Expert Committee made the same recommendation, the CND assented in 1991 (IDPC, 2007).

The 2002 WHO Expert Committee made another critical review, and partly in view of the increased medical use of dronabinol, recommended its reclassification to Schedule IV, the least restrictive schedule. The Executive Director of the UNODC persuaded the Director-General of WHO not to forward this recommendation, claiming it would “send a wrong signal and create a tension with the 1961 Convention” (IDPC, 2007). The 2006 WHO Expert Committee reconsidered and updated the review. Hesitating between Schedules III and IV, it finally recommended transfer to Schedule III as a small step forward. In its Report for 2006 and at the 2007 CND plenary, the INCB spoke out against the recommendation, expressing concern “about the possibility of dronabinol, the active principle of cannabis, being transferred to a schedule with less stringent control” (INCB, 2007). In the 2007 CND debate on this, the US was strongly opposed, and many other countries fell in line. Canada commended the WHO Committee for its “excellent expert advice”, but did not support rescheduling because it “may send a confusing message with regard to the risks associated with cannabis use” (IDPC, 2007). The recommendation was sent back again for reconsideration by the WHO “in consultation with the INCB” - although the INCB has no formal role in scheduling under the treaties.

A SYSTEM IN STALEMATE

Cannabis has lately come to play an important role in the international drug control regime at the rhetorical level. The annual statements of the UNODC always mention the estimated share of the world population that use illegal drugs. That number is dominated by cannabis. For example, in the 2005 World Drug Report the UNODC stated that there were 200 million drug users globally; of these 160 million (80%) used cannabis. The other drugs listed (ATS, cocaine and opiates) had user populations totaling only 40 million, less than 1 percent of the world’s population. Without cannabis, the totals would suggest that illegal drug use is not a global population-level issue. Thus the drug helps give breadth to the drug issue globally; the same is true in many member nations.

Nor, despite the moves to a less punitive regime in some countries, is the prohibition regime at risk. For example, in 2008 the British government, with Prime Minister Gordon Brown leading the way, and against the advice of the official expert advisory committee, increased the severity of penalties for drug possession and sale,15 reversing an easing of penalties that occurred in 2004. The maximum penalty for supplying has been raised to 14 years; possession penalties have been raised to a maximum of five years. The rationale for this change, achieved primarily through the revision of the scheduling of cannabis from Class C to Class B, is primarily the new evidence discussed in Chapter 2 of an association between cannabis use and psychosis, particularly schizophrenia.

The event serves as a useful reminder that efforts to reverse cannabis prohibition or to substantially lessen the severity of the regime can readily be reversed. Popular support for cannabis prohibition is surprisingly strong. Eurobarometer, the principal survey of opinion in the European Union, reports that only about one quarter of respondents favored the legalization of simple possession of cannabis. Support for major changes in the legal status of marijuana possession laws has also been low in the United States for the thirty-odd years that the Gallup poll has asked the question. This provides a base of support for increasing the severity of penalties when perceptions of the potential dangers of the drug increase.

As discussed, however, there is minimal evidence that changes in statutory penalties would reduce cannabis use. The lack of evidence of a deterrent effect has to be weighed against the considerable harms that undoubtedly arise from the existing regime. Cannabis is a drug used by very large proportions of the populations of many Western countries. There is a large-scale black market that is an unintended consequence of the existing system of prohibition, as acknowledged recently in an essay by the Executive Director of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (Costa, 2008). The cannabis market causes less harm than similarly-sized black markets for cocaine and heroin since it is associated with less violence and probably less corruption; the latter is a consequence of the more dispersed production and shorter distribution chains. Nonetheless, a global black market of tens of billions of dollars represents in itself a challenge to the authority of governments.

The arrests of many hundreds of thousands of cannabis users in the Western world might also be called a harm. That might not be the case if arrest were typically the prelude to provision of treatment, as is increasingly the case for heroin in some countries such as the United Kingdom, and if those arrested were likely to be users with treatable problems. However, there is nothing about the arrest process that suggests that it targets high-rate and problematic users; instead, it seems that arrestees are users who are unable to act discreetly or who simply are unlucky. A modest percentage of arrestees are referred to treatment. Thus, unless there is evidence of deterrent effect, arrest in itself seems to cause harm to some users without many compensating benefits. We note, though, that in most countries there is little formal punishment beyond the arrest itself. It is, accordingly, important not to exaggerate the severity of the harms suffered by arrested users.

Finally, there must be a nagging concern about the fairness with which cannabis laws are enforced. The small amount of available evidence suggests that police often use the charge of cannabis possession as an easy way of harassing or making life difficult for marginalized populations. It is often an excuse for intrusion into their lives, allowing a search which might turn up something else of interest for the police.

In the next two chapters, we turn to the various efforts and experiments which have been made at national or subnational levels to ameliorate these harms, considering first the nature and scope of the efforts, and then the evidence on their effects.

1 As this book was being written, a new cross-national study of substance use was released (Degenhardt et al., 2008). It presented data on lifetime prevalence and age of initiation for 17 countries that participated in the World Mental Health Survey (WMHS). Since methodology in this study was more uniform than in any previous comparison of cannabis use across countries, it would be appear to be the most authoritative source for such statements. However, there are large discrepancies between the findings reported in Degenhardt et al. and other well known surveys; for example, for 15-16 year olds in the Netherlands, ESPAD reports a lifetime prevalence rate of 28% while the WMHS shows only 7% for 15 year olds. Consequently, we have not made use of the WMHS data until these discrepancies, which may represent important methodological differences, are accounted for.

2 The UNODC offers data on regional prevalence rates, but the underlying data sources are opaque, and in some cases it is clear that no systematic data collection underlie the estimate.

3 This is consistent with national data. For example, in the Kandel & Davies study over 70% reported use at some time prior to the interview. The closest comparison is with the 1979 NHSDA 18-25 year olds - i.e., those born between 1956 and 1961. This comparison is appropriate because most initiation occurs before age 20. The NHSDA figure for lifetime use of marijuana was 68%; no data are available on the two-year birth cohort of 1955-1956.

4 Since cannabis herbal resin is almost unknown in the United States, we generally refer to marijuana rather than cannabis in citing US figures.

5 These data come from seizures of marijuana primarily though not exclusively from federal agencies. If law enforcement authorities are more likely to seize imported than the domestically produced drug, then they will probably underestimate the potency, since the domestic is more likely to have been grown with high potency.

An increase in the share that is domestically produced will tend to lead to an increase in the difference between the market average and the average recorded in the test data.

6 The data are from STRIDE (System to Retrieve Information from Drug Evidence), which includes data on all seizures and purchases of drugs by federal agencies and from a few state and local agencies. For a discussion of the strengths and weaknesses of STRIDE see Horowitz (2001) and Caulkins (2001).

7 For a discussion of the absurdity of earlier estimates of US estimates of Mexico’s marijuana production, see Reuter (1995).

8 As might have been expected, it was those who used less frequently that were most likely to have received the drug for free. A far smaller share of the quantity consumed was given away free.

9 No data exist in the United States for prosecutions by drug type. The statement is simply an informed judgment.

10 Weatherburn and Jones do the calculations of rates for those who were arrested for cannabis possession only; these constitute about 40 percent of all arrests involving the charge of cannabis possession. The figures reported here include the larger population of arrests.

11 Another potential problem is that prevalence of use may influence the state’s decision about how many arrests to make, just as arrests may influence prevalence.

12 The comparisons offered here are only for the longer-term EU countries (the 15 members in 2004, before additional members were admitted), since most of the new members were still in transition in terms of drug use prevalence.

13 Montanari, Taylor and Griffiths (2008) report that the data on frequency of use among those seeking treatment appears to be quite poor. Nearly thirty percent report either no use or infrequent use in the month before admission, which is an unlikely figure except perhaps for criminal-justice referrals.

14 A further issue on cannabis was announced at the 2008 CND sessions (IDPC, 2008).

15 The Home Office announcement of the change in policy can be found at http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/drugs/drugs-law/cannabis-reclassification/

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|