2. Cannabis in Switzerland: The current situation

| Reports - Swiss Federal Commission For Drug Issues |

Drug Abuse

2. Cannabis in Switzerland: The current situation

2. Cannabis in Switzerland: The current situation

2.1 Prevalence of cannabis use

2.1.1 Development of cannabis use from 1970 to 1998

A number of studies of drug and, more particularly, cannabis use in Switzerland have been carried out since the early 1970s. Not all of them used the same methodology, so the findings are not comparable in strictly scientific terms. However, they do give a good impression of the magnitude of the problem. The term "prevalence" is often used to describe the extent to which a drug is used. It shows how often a drug is consumed during a defined period of time (e. g. the lifetime prevalence is the number of individuals who have used the drug at any time in their life). The consumption of cannabis by Swiss adolescents is not a new phenomenon. As long ago as 1971, the lifetime prevalence of cannabis consumption among 19- year- old men required to enlist for military service in the canton of Zurich was 23.3 percent, and the figure for a comparison population of women was 13.5 percent. At that time 8.2 percent of the men and 3.5 percent of the women had had frequent experience of cannabis (had used it more than ten times). In another study in 1978, also carried out in the canton of Zurich among 19- year- olds, the lifetime prevalence of cannabis consumption was only 19.9 percent for men but 17.2 percent for women. Frequent use (more than ten times) had increased to 8.5 percent among the men and 5.7 percent among the women (Sieber 1988). In a survey of recruits from all parts of Switzerland carried out in 1972/ 73, the lifetime prevalence of cannabis consumption was 20.1 percent, with 5.7 percent claiming frequent use (more than six times) (Battegay et al 1977). An evaluation of the pedagogical examinations of recruits carried out in 1993 showed the lifetime prevalence to be around 44 percent, with frequent use (more than ten times) at 18.5 percent (Wydler et al 1996).

A written questionnaire distributed by Wydler et al in 1993 showed a 12- month prevalence of 32.1 percent among young men aged 20 and 16.8 percent among women of the same age. The most recent data were compiled during a telephone survey commissioned by the Swiss Institute for the Prevention of Alcohol and Drug Problems (SFA/ SIPA) in February 1998:

Percentage of respondents (N= 1019, excluding Italian- speaking Switzerland) who had used cannabis in the preceding 12 months, February 1998

| Men | Women | Total | |

| Ages 15 to 19 | 37.5 | 24.0 | 29.9 |

| Ages 20 to 24 | 24.3 | 20.1 | 22.2 |

| Ages 25 to 29 | 17.8 | 16.1 | 16.9 |

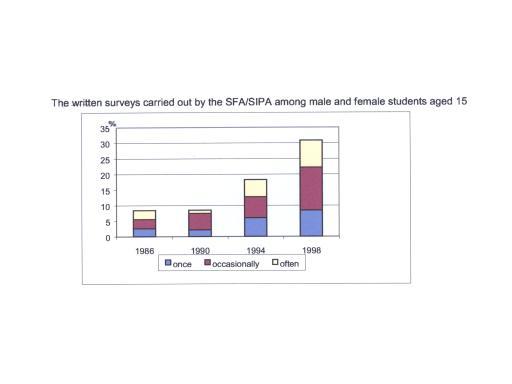

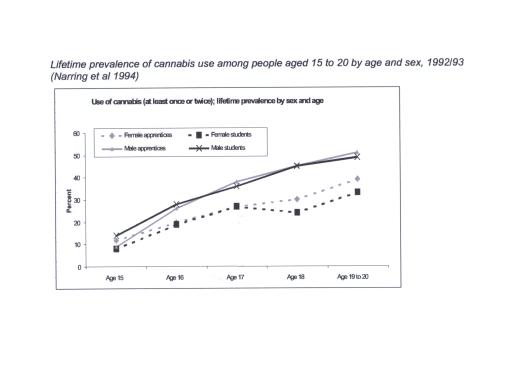

The written surveys carried out by the SFA/ SIPA among male and female students aged 15 show a clear increase in cannabis consumption between 1986 and 1998. The proportion of 15- year- olds with experience of cannabis more than tripled over the last12- years. In 1986, 2.5 percent reported having used this soft drug once, in 1998 the figure was 8.4 percent. In 1986, 3 percent used hashish or marijuana "occasionally", by 1998 the figure was four- and- a- half times higher (13.8 percent). In 1986, 2.9 percent used cannabis frequently, in 1998, 8.6 percent. A study by Narring et al in 1992/ 93 of the health- related behaviors of young Swiss people aged 15 to 20 largely confirmed the findings of the college study of 15- year- olds. The study showed that above age 18, almost half of young men have used cannabis at least once, although 30 percent of them state that they have only used it once or twice. The figures are around 10 percent lower for women.

Cannabis use is more common among younger people, but a study in 1987 (Fahrenkrug, Müller 1990) showed that 20 percent of people over 34 had used cannabis at some time. As many as 12 percent of those aged 35 to 44 and 5.8 percent of those aged 45 to 54 had also used cannabis at least once in their lifetime. Extrapolated to the entire population, this would mean that some 550,000 people aged between 15 and 74 had used cannabis at that time. According to the Swiss Health Surveys for the years 1992/ 93 and 1997/ 98, the lifetime prevalence for the age group 15 to 39 in Switzerland rose from 16.3 to 26.9 percent during this period. Extrapolated to the entire population of the country, some 685,000 Swiss people between the ages of 15 and 39 in 1998 had used cannabis at some time. An increase is also discernible among current users: in the period 1992/ 93, 4.4 percent of those surveyed were using cannabis products, while in the period 1997/ 98 the corresponding figure was 7.1 percent.

Little information is available on the age at which illegal drugs are first consumed. It is difficult to find such data since most studies provide only data from cross- sectional analyses. Calculations based on survival models for drug users show that the age at which drugs are first consumed has not changed greatly in recent years; it has remained at around 16 (Gmel, Rehm 1996).

2.1.3 International comparison

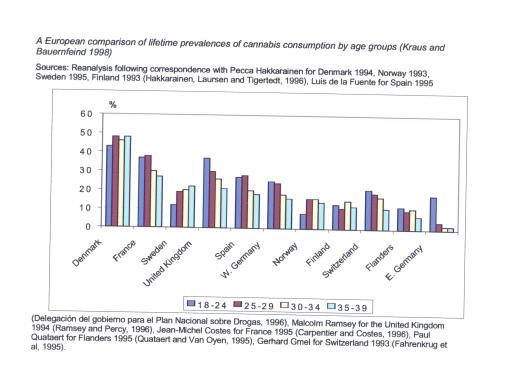

It is difficult to compare drug use on an international scale because the groups surveyed, the times at which they are surveyed and the types of survey differ so widely between countries. Against this background, the attempt made by Kraus and Bauernfeind (1998) to draw up an international comparison of the lifetime prevalence of cannabis use should be approached with caution. Switzerland ranges in the middle field among the nine countries for which lifetime prevalences are shown in the illustration below; the Scandinavian countries have lower prevalences, Denmark, France, the United Kingdom and Spain have higher figures. One striking feature is the fairly similar overall figures for Spain, West Germany, Sweden and Switzerland, although the cannabis policy in these countries differs considerably (Cattacin, Renschler 1997).

In most European countries there was a slight to moderate increase in the prevalence of cannabis consumption during the 1980s (Kraus, Bauernfeind 1998). However, the report on Europe issued by the WHO in 1997 gives a mixed picture of the trends in cannabis consumption in this region from the early to mid- 90s. The nine western European countries that provided information on trends in cannabis use all reported an increase in consumption, but within these countries the patterns are very different from one region to another.

References

Battegay R et al (1977). Alkohol, Tabak und Drogen im Leben eines jungen Mannes. Untersuchung an 4082 Schweizer Rekruten betreffend Suchtmittelkonsum im Zivilleben und während der Rekrutenschule . (Ed.) G. Ritzel, Basel. Sozialmedizinische und pädagogische Jugend , Karger, Basel.

Cattacin S and Renschler R (1997). Cannabispolitik: Ein Vergleich zwischen 10 Ländern. In: Abhängigkeiten, 5, 31- 43.

Kraus L and Bauernfeind R (1998). Konsumtrends illegaler Drogen in Deutschland: Daten aus Bevölkerungssurveys 1990- 1995. In: Sucht 44 (3) 1998, 169- 182.

Fahrenkrug H and Müller R (1990). Soziale und präventive Aspekte des Drogenproblems unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Schweiz . Commissioned by the Federal Office of Public Health. Swiss Office for Alcohol Problems, Lausanne/ University of Lausanne/ DEEP- HEC.

Gmel G and Rehm J (1996). Zum Problem der Schätzung des Alters beim Drogeneinstieg in Querschnittsbefragungen am Beispiel der Schweizerischen Gesundheitsbefragung. In: Soz. Präventivmed. 1996, 41: 257- 261. Birkhäuser Verlag, Basel.

Müller R (1990). Soziale und präventive Aspekte der Drogenproblems unter spezifischer Berücksichtigung der Schweiz. Commissioned by the Federal Office of Public Health. Swiss Institute for the Prevention of Alcohol and Drug Problems (SIPA).

Müller R (5.8.98), SFA, Der Cannabisgebrauch in der Schweiz. Narring F et al (1994). Die Gesundheit Jugendlicher in der Schweiz. Bericht einer gesamtschweizerischen Studie über Gesundheit und Lebensstil 15- bis 20jähriger. Cahiers de recherches et de documentation. University Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine, Lausanne.

Rehm J (1994). Aktuelle Prävalenz des Konsums illegaler Drogen in der Schweiz. Neue Daten aus der Schweizerischen Gesundheitsbefragung 1992/ 93. In: Drogalkohol No. 2/ 94. ISPA- Press, Lausanne.

Sieber M (1988). Zwölf Jahre Drogen. Verlaufsuntersuchung des Alkohol-, Tabak- und Haschischkonsums. Verlag Hans Huber, Bern.

Wydler H et al (1996). Die Gesundheit 20jähriger in der Schweiz. Ergebnisse der PRP 1993. Pädagogische Rekrutenprüfung. Wirtschaftliche Reihe volume 14. Verlag Sauerländer, Aarau and Frankfurt am Main.

2. Cannabis in Switzerland: The current situation 2. 2 Availability and trade

Cannabis may be used legally as a renewable raw material in the textile, oil, paper, rope and construction industries and in the production of foodstuffs and consumer goods; it is also consumed illegally as a narcotic (marijuana, hashish, hash oil). There has been a sharp increase in cannabis cultivation in Switzerland recently, with the resulting products destined not only for the legal market but also, and more particularly, for illicit consumption as narcotics (" drug- grade cannabis").

| Year | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 |

| a) Renewable raw material¹ | 0 | 10 | 11 | 6 | 2 | 60 |

| b) Other uses² | 1 | 10 | 50 | 150 | 200 | ~250 |

Table 1: Area under cannabis cultivation (ha) in Switzerland and uses

¹ Figures from the Federal Office of Agriculture (BLW)

² Estimate from BLW documentation

The drug grade has a THC * content in excess of 0.3 percent (see 2.3); the industrial or fiber grade contains less than 0.3 percent THC. Since even experts cannot distinguish "industrial cannabis" from "drug cannabis" with the naked eye, it is not possible to tell what type of cannabis is being cultivated unless the plants are analyzed chemically. The figures for b) in the above table have therefore been classified as "other uses" even though it has to be assumed that these crops are used predominantly to produce "drug cannabis".

*THC: The active principle is tetrahydrocannabinol (cf. Chapter 2.3). In this report only the abbreviation THC will be used (except in Chapters 2.3 and 2.5).

2.2.1.1 Cannabis in agriculture

The cannabis plant is well adapted to the geography, soil and climate in Switzerland. It makes few demands on the soil and can generally be grown without the aid of chemical crop protection agents. As such it is an ideal candidate for integrated production (IP) and ecological cultivation. From an agronomic point of view, the prospects for the successful reintroduction of industrial cannabis production are excellent. There is major public interest in ecological products derived from sustainable resources. Cannabis is a promising plant which is easy to grow and provides a high quality raw material. This is why the "renewable raw materials" project being run by the Federal Office of Agriculture (BWL) is funding the cultivation of low- THC cannabis (containing less than 0.3 percent THC) for industrial purposes.

Switzerland has had a type list 1 covering the marketing of cannabis seed for agricultural purposes since 1 March 1998. This list restricts trade in cannabis seeds and plants to varieties containing low levels of THC. The cultivation of cannabis and activities outside the agricultural context (e. g. ornamental plants) are not covered by this regulation.

2.2.1.2 Cannabis for food products, cosmetics and consumer goods

The flowers, seeds, fatty and volatile l oils, and other parts of the hemp plant are currently used to manufacture foodstuffs and cosmetics. A variety of products including hemp oil, biscuits, chocolate, confectionery, pasta, "beer flavored with hemp blossom", and a number of skin and hair care products can be purchased. Food products and cosmetics containing hemp are not permitted to have any pharmacological activity. The revision of the Ordinance on Foreign Substances and Ingredients in Food Products (FIV) dated 30 January 1998 established threshold values for the THC content of various foods 2 . By analogy with the FIV, a limit of 50 mg/ kg is applied to cosmetic products which are left on the skin. The situation in the food and cosmetics sector has eased considerably since these threshold values were introduced. Most of these cannabis products are sold in so- called hemp shops (in 1998 there were around 135 such shops in Switzerland). However, hemp shops sell not only legal products but also illicit cannabis products (cf. 2.2.2 Illegal use and 2.7 Enforcement of the existing legislation).

2.2.1.3 Medical use of cannabis

Chapter 2.5 deals specifically with the therapeutic use of the pharmacological effects of cannabis, or THC, in medicine.

The cultivation of drug- grade hemp and the associated sales of products made from this hemp are increasing from year to year in Switzerland. Relevant data from a number of cantons show that a large quantity of products based on drug- grade hemp are already being exported, and that an increasing volume of equipment and other items used in hemp cultivation and to produce marijuana and hashish are being imported into Switzerland. It can be assumed on the basis of a survey covering all cantons that most of the illegal trade in hashish is still carried out on the street, as it always has been. "Hemp shops", on the other hand, are increasingly the channel through which marijuana is sold; most of it is packed into and sold in the form of "aromatic pillows". In Ticino canton practically the entire cannabis market has gravitated towards "hemp shops". The police view is that the vast majority of hemp fields in Switzerland are used to produce cannabis supplied to the drug trade. It can be assumed that in 1998 considerably more than 100 metric tons of drug- grade cannabis were harvested. Today Switzerland has an almost nationwide network of 135 hemp shops. The big increase started in 1996 and led to the creation of major centers in the city and canton of Zurich (a total of 36), in the canton of St. Gallen (18), in Ticino (16) in Basel (7) and in the canton of Berne (6). Police information shows that between 85 and 95 percent of sales in most hemp shops come from drug products (" hemp pillows", "aromatic bags", "refills for aromatic bags", "hemp coins" etc.) The THC content of cannabis sold in "aromatic bags" is frequently between 8 and 10 percent, for example. The people who sell hemp products (in hemp shops) claim that their products (such as "aromatic pillows") are not intended for making drugs, and that it is therefore legal to sell them. It is up to the public prosecution agency to gather additional evidence and prove that the cultivation of hemp or the product in question is intended for making illegal narcotic substances or for consumption as an illegal drug. Chapter 2.7 deals with the difficulties faced by the prosecution authorities in distinguishing between legal and illegal use when inspecting areas used to cultivate cannabis and hemp shops.

1 Ordinance on the Production and Marketing of Seeds and Plants, as revised on 25 February 1998, and Ordinance of the Federal Office of Agriculture on the Varieties Catalog for Cannabis, 26 February 1998.

2 A limit of 50 mg THC/ kg applies to oils for culinary use; the maximum content in pasta, biscuits and cereal bars is 5 mg THC/ kg dry mass, and in beverages (including teas) 0.2 mg THC/ kg.

The cultivation of hemp for consumption has reached industrial proportions in Switzerland in the last few years. In 1997, 7.2 metric tons of hemp products and 313,258 hemp plants were impounded. Although reliable data are difficult to come by, it can be assumed that Switzerland has become a hemp- exporting country and is one of Europe's two major producers, the other being the Netherlands. Hemp is also being cultivated increasingly in private gardens and on balconies. This may be partly because hemp is an attractive ornamental plant; in many cases, however, this cannabis is no doubt intended for consumption. This report will not look at hemp cultivation in greater detail. The current situation and the related problems are described in the relevant documentation compiled during the amendment of the Swiss Narcotics Act, which was scheduled for distribution to the cantons for comment during the summer of 1999. Models which the Commission feels could be suitable for hemp cultivation are described in Chapters 3 and 6.

2.3. Pharmacology and toxicology of cannabis

Note on this chapter: In some places the following text goes into far more detail than the other chapters in this report. This exhaustive approach was taken deliberately, since an understanding of the complex effects of cannabis is vital for an objective discussion of the subject in hand, and very little summarizing literature is available on the aspects portrayed here. The reader not familiar with the biological terminology can omit the paragraphs printed in italics and smaller type without losing the essence of the text.

According to the current system of botanical classification, hemp belongs to the genus Cannabis which, together with the genus Humulus – hops, are included in the Family Cannabidaceae (Hagers Handbuch [...] 1992). Although the wide variety of characteristic features would suggest that there are several species of cannabis, today only one collective species is recognized, Cannabis sativa (Lehmann 1995). The other species commonly referred to, Cannabis indica – Indian hemp, is in fact a subspecies of Cannabis sativa (Fankhauser 1996). Cannabis sativa is a dioecious, green, leafy plant with characteristic opposite, usually sevenfingered, lance- shaped leaves; on dry, sandy, slightly alkaline soil it can grow to more than 7 meters in height. Glandular hairs develop, usually on the female flower, which secrete a resin. The greatest density of glandular hairs is found on the sepals and on the underside of the last leaves to form (Geschwinde 1996). The female plants are more important than the male plants for commercial purposes: their fibers are thicker, they form the nutritious seeds, and they contain the psychoactive principle tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) which is much sought after by producers of marijuana and hashish. Unlike most of the substances used in our western culture to induce an intoxication, cannabis is not a single substance but contains a large number of different components; over 420 have been identified to date. The cannabinoids, of which there are over 60, are the most important class containing the active principle responsible for the psychotropic effects of the plant, (-)- trans- 9 -tetrahydrocannabinol (referred to in the following as 9 -THC). Basically all the parts of the Cannabis sativa plant can contain cannabinoids, not just the seeds, but the quantity varies from one part to another. The resin secreted by the female glandular hairs contains up to 90 percent cannabinoids, the bracts of the flowers and fruits contain an average of 3 to 6 percent, and the leaves contain only 1 to 3 percent (Geschwinde 1996). The fiber grade of cannabis is cultivated for industrial purposes, and the legislation in the European countries requires this type to contain no more than 0.3 percent THC (see also 2.2.1). The most important cannabis products in the drug trade are marijuana and hashish. Marijuana consists of all the dried parts of the plant; it is sold either loose or pressed and contains up to 2 percent THC. The THC content is increased (up to 6 percent) by using only the flowering tops of the female plants. Hashish is a particularly resinous form of cannabis, and good quality hashish contains between 10 and 20 percent THC (Lehmann 1995). The THC content of cannabis plants can be increased by selective breeding and optimal growing conditions. The ”Sinsemilla” type of marijuana, for example, had a THC content of 1 percent in the 1960s, 8.5 percent in the early 1980s, and as much as 17 to 22 percent in the 1990s (Adams, Martin 1996; Geschwinde 1996).

2.3.2.1 Absorption, metabolism and excretion

Cannabis is usually smoked as a "joint", a variable mixture of hashish (or marijuana) and tobacco. The dosage depends on the desired effect (generally one cigarette containing 2 percent THC). The active principle is absorbed very rapidly via the respiratory tract and lungs, with an onset of action just a few minutes later. The effect peaks at 15 minutes, subsides gradually after 30 to 60 minutes, and is largely finished after 2 to 3 hours (Geschwinde 1996). The bioavailability (proportion of substance active in the body) depends greatly on the smoker's technique and varies between 10 and 25 percent (with a maximum of 56 percent). THC is absorbed by the body much more slowly after oral intake (eating or drinking) and then has a lower bioavailability of 4 to 12 percent because of the poorer absorption, catabolism in the liver and the fact that the inactive tetrahydrocannabinolidic acids in natural cannabis products cannot be transformed into psychoactive 9 -THC unless they are heated first, as is the case when they are smoked (Lehmann 1995). In contrast to absorption through the respiratory tract, in which peak plasma concentrations of THC may be achieved while the product is being smoked, the plasma concentration increases constantly over a period of 4 to 6 hours when cannabis is ingested; a state of intoxication is reached later and is of a different quality.

The high solubility of 9 -THC and its active metabolite 11- OH- 9 -THC in fat mean that they are bound almost completely to protein in the plasma, cross the blood- brain barrier with ease, and are eliminated only slowly from lipid- containing tissue. This slow elimination gives the substances a biological half- life of one day (Lehmann 1995); other authors have reported half- lives of three to five days (Adams, Martin 1996). The substances are thought to be metabolized twice as quickly by chronic users of cannabis as by first- time users (Adams, Martin 1996; Maykut 1985).

The relationship between plasma concentrations and the degree of intoxication is discussed in Chapter 2.3.5 (Cannabis and driving).

The cannabinoids are metabolized rapidly in the liver. To date, some 80 different, mostly inactive metabolites have been identified (Agurell et al 1986). No major metabolic differences between male and female users of cannabis have been observed (Wall et al 1983).

Specific research into the mode of action of cannabis was not possible until 1964 (Agurell et al 1986), when 9 -THC was isolated and its structure was elucidated. It then became possible to develop substances with an action similar to THC, some of them highly potent. During the 1980s, various scientific findings removed any lingering doubt about the existence of specific cannabis receptors (Bidaut- Russel et al 1990; Dewey et al 1984; Howlett, Fleming 1984; Howlett et al 1986).

A cannabinoid receptor (CB1) located predominantly in the cerebellum, the hippocampus and the cerebral cortex was finally discovered and cloned in 1990 (Axelrod, Felder, 1998). A further, peripheral, receptor (CB2) was found in certain parts of the immune system (e. g. the spleen) in 1993 (Abood, Martin, 1996; Lehmann, 1995). Investigations carried out to date would seem to confirm that these receptors are capable of affecting neurophysiological processes in the brain (Axelrod, Felder, 1998). Future research will reveal the extent to which processes of this type involving cannabinoid receptors are linked to the complex effects of cannabis in humans.

In 1992 the endogenous ligand (linking substance) anandamide was discovered; it is thought to be synthesized and released on an ad hoc basis (Abood, Martin 1996; Axelrod, Felder 1998; Di Marzo et al 1994).

The discovery of the cannabinoid receptors, endogenous ligands, and the development of specific agonists and antagonists in the past and the future, are making a major contribution to scientific understanding of the effects of cannabis, of the neurophysiological role played by thes receptors, and of the possible effects on the human brain and its functions in the context of chronic cannabis use. New knowledge will perhaps enable us to develop an active principle which is therapeutically highly active but has none of the psychoactive properties.

2.3.3 Acute effects of cannabis on the central nervous system

The psychotropic (affecting the central nervous system and the mind) action of cannabis is one of the reasons why cannabis products are used so widely. As mentioned above, cannabis starts to act more rapidly and more intensively when it is smoked, and the intoxication lasts a shorter time, than when it is absorbed through the digestive system. The effect of cannabis depends not only on its composition, dosage and mode of consumption; much also depends on the mood of the individual, on the individual's expectations and on the atmosphere and setting. These factors explain why the altered state of consciousness, which may amount to pronounced intoxication, is experienced so differently by different people. At a low to moderate dose, cannabis produces a largely pleasant feeling of relaxed euphoria, perhaps even with dreamy elements, which may be accompanied by heightening or alteration of the senses (Hagers Handbuch [...] 1992). The sense of time shifts markedly, and the individual perceives periods of time as being considerably longer than they really are. Short- term memory is impaired (Lehmann 1995), although recall of previously acquired knowledge is impaired only slightly if at all. It is uncertain whether other higher functions of the brain, such as the organization and integration of complex information, are affected (Adams, Martin 1996). Higher doses produce a general reduction in spontaneity, drive and involvement in the surroundings. Anxiety, confusion, aggressive feelings, (pseudo) hallucinations, nausea and vomiting have all been reported but are not usually experienced. They may, however, develop even in experienced users (Hagers Handbuch [...] 1992; Lehmann, 1995). As the effects of THC subside, the individual often becomes drowsy and tired, but there is no "hang- over" comparable to the effect experienced after heavy alcohol consumption.

2.3.4 Acute side effects and toxicity of cannabis

The physiological effects observed immediately after consumption are reddening of the conjunctivae, a reduction in body temperature, a dry mouth and throat, hunger, a slightly elevated heart rate and blood pressure when lying down, and a drop in heart rate and blood pressure when standing (Adams, Martin 1996; Dewey 1986; Hagers Handbuch [...] 1992). The acute toxicity of cannabis is generally thought to be low. If the dose of cannabis lethal in rhesus monkeys is extrapolated to man, a human would have to smoke 100 grams of hashish to achieve the same effect. No fatality has ever been reported in connection with acute cannabis intoxication either in Switzerland or elsewhere. Deaths overall are very rare following cannabis consumption, and are generally a consequence of the potentially increased inclination to suicide associated with an atypical course of intoxication (Hagers Handbuch [...] 1992). Use of high- dose cannabis products can lead to psychotic states which manifest as a combination of emotional symptoms, such as fluctuating mood, disorientation and schizophrenia- like states, and depression, anxiety, visual and auditory hallucinations and paranoid persecution mania. Panic reactions are often due to the individual's fear of losing control or his/ her mind. The treatment of such states often involves nothing more than reassuring the person. Drug therapy is generally unnecessary because the calming effect of the drug in any case comes to the fore as the intoxication subsides (Hagers Handbuch [...] 1992; Hollister 1986). When evaluating the significance of the potential negative effects of cannabis consumption mentioned above, it should not be forgotten that similar effects may also occur in patients using many of the psychoactive medications prescribed today.

Relationship between plasma concentration and degree of intoxication A number of studies have attempted to correlate plasma concentrations of 9 -THC and its metabolites with the psychoactive effects of cannabis in order to deduce the extent of the intoxicated state currently being experienced by an individual, or to determine when cannabis was last used. However, this is far more difficult than with alcohol because of the many factors that affect the pharmacological action of cannabis. Peak plasma concentrations do not correspond to the point of maximum intoxication when cannabis is inhaled (smoked), injected intravenously or ingested (eaten or drunk) (Cochetto et al, 1981). More recent mathematical models are thought to permit more accurate assessment of the time that has elapsed since cannabis was last consumed (WHO 1997).

Of particular interest in view of the widespread use of cannabis is its effect on the individual's ability to drive and operate machinery. Numerous studies of the effects of cannabis on psychomotor function and analysis of road traffic accidents following which THC and/ or alcohol have been detected in the plasma have produced inconsistent results. The most important aspect is how long cannabis is likely to affect the ability to drive after it has been taken. The reduced reaction speed and altered perception, alertness and ability to process information mean that cannabis is likely to impair the ability to drive as much as two to four hours after being smoked (up to a maximum of eight hours) (Adams, Martin 1996; Hollister 1986; Iten 1994; WHO 1997). It has been reported that cannabis users often overestimate the effect of cannabis on their ability to drive, and often drive slowly with great concentration, while individuals under the influence of alcohol tend to overestimate their driving skills (Adams, Martin 1996). However, it has also been noted that in 80 percent of road traffic accidents involving THC in the plasma alcohol had also been consumed (WHO 1997).

2.3.6 Medical uses of THC and cannabis

The therapeutic use of the pharmacological effects of cannabis and THC in medicine is the central theme of Chapter 2.5.

2.3.7 Effects of chronic cannabis use

Opinions differ, in some cases widely, on the effects of chronic cannabis use, and the results obtained from research to date leave room for assumptions and speculation. It appears to be practically impossible to demonstrate effects due solely to cannabis. It is difficult to extrapolate from animal experiments, some of which use high doses of pure substance and whose duration is too short to be comparable with chronic use of marijuana, to man. Even in clinical trials with chronic cannabis users, the results will be falsified for example, if the individuals studied have been consuming alcohol and tobacco for the same length of time. For this reason it is not possible to attribute the results solely to the use of cannabis with any degree of certainty. Moreover, the number of other possible causes of the effects observed grows as the duration of use gets longer (WHO 1997).

2.3.7.1 The Amotivational syndrome

Acute, reversible psychotic states have been documented in exceptional cases following cannabis use, but the existence of "the amotivational syndrome", first described in the literature in 1968, has never been confirmed. The term was used to describe the changes in attitude and personality, the neglect of appearance and general disinterest displayed by chronic users of cannabis, although nowadays it is considered to be obsolete and not typical of cannabis consumption (Huw 1993; WHO 1997). It is exceptionally difficult – if not impossible – to establish a direct and exclusive causality between speculative consequences of chronic cannabis use and the drug itself. For example, studies attempting to link dropping out of school at an early age with cannabis use have tended to show that it was in fact the family background, the child's relationship with its parents during its school years, social values, etc. which led the child to stop going to school (Hollister 1986).

2.3.7.2 Dependence and tolerance

Cannabis consumption can lead to psychological dependence; it is estimated that around half of heavy users develop dependence of this type (WHO, 1997). In a German study, one in five respondents admitted to frequently or very frequently consuming more cannabis than they had intended to (Kleiber et al 1997). The tendency to develop physical dependence is only weak. It has been demonstrated in animal experiments by administering an antidote (the receptor antagonist SR 141716A) following chronic administration of cannabis and observing withdrawal symptoms (Aceto et al 1995). Abrupt withdrawal in humans following heavy daily consumption produces autonomic withdrawal symptoms such as nausea, perspiration, trembling, insomnia and loss of appetite (Hollister 1986; Wiesbeck et al 1996). These symptoms regress following renewed administration of cannabis, an observation that corroborates the development of dependence (Adams, Martin 1996). The the dependence profile is classified by the World Health Organization as a distinctive type of dependence, known as cannabis- type dependence.

The development of tolerance is associated with pharmacodynamic changes. Chronic administration of THC has been shown to reduce the number of receptor binding sites (Rodriguez de Fonseca et al 1994), although this appears to be reversible (Westlake et al 1991). The tolerance to the functional and psychological effects of THC observed in animal experiments has also been demonstrated in man, but does not lead the individual to increase the dose of cannabis (Beardsley et al 1986; Hollister 1986). Clear tolerance development has been demonstrated with respect to mood swings, elevated heart rate and impairment of psychomotor functions. The conditions under which tolerance and dependence develop – high doses of THC over a long period – do not correspond to the widespread recreational use of cannabis, and this is why these properties of cannabis do not present a serious problem.

Cannabis is probably the most widely smoked substance in the world after tobacco. In addition to the nicotine in tobacco and the cannabinoids in cannabis, the matter inhaled from both substances contains a large number of other compounds which irritate the respiratory tract and have carcinogenic (cancer- causing) properties (Julien 1997). The effects of tobacco and cannabis on the respiratory system are very probably not additive (WHO 1997), or in other words they cannot simply be added together. However, the cannabis smoker inhales more deeply than the tobacco smoker, allowing four times the quantity of tar to enter the lungs (Hagers Handbuch [...] 1992). Bronchial irritation and inflammation, reduced macrophage and cilia activity (making the removal of particles from the lungs more difficult) and changes to the mucous lining of the respiratory tract have been observed in heavy users of hashish (Hollister 1986; Julien 1997). In general, studies of longstanding cannabis smokers have demonstrated damage to the mucosa in the trachea and bronchi (WHO 1997). Smoking cannabis products is therefore assumed to be associated with an increased risk of lung and bronchial cancers. However, it is difficult to consider the carcinogenicity of cannabis in the lung in isolation because hashish and marijuana smokers are usually also cigarette smokers as well – quite apart from the fact that these two cannabis products are generally smoked in a mixture with tobacco anyway (Hagers Handbuch [...] 1992).

2.3.7.4 Genetic effects and effects on reproduction and pregnancy

An increased rate of chromosomal abnormalities, mainly chromosome breaks and translocations, has been observed among marijuana smokers (Hollister 1986). Changes at the cellular level were reversible in clinical trials (WHO 1997). The clinical significance of these observations is disputed, not least because similar changes can occur in individuals taking commonly prescribed drugs on a daily basis (Hollister 1986; Maykut 1985).

The effects on the concentration of testosterone, estrogen and prolactin in plasma observed in animal experiments have not been reproduced unequivocally in clinical trials with humans (WHO 1997). In women, cannabis consumption leads to lower levels of follicle- stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH), and may affect the menstrual cycle, although these effects are evidently reversible and disappear once the drug is discontinued (Hollister 1986; Maykut 1985).

The good lipid solubility of the cannabinoids allows them to cross the placenta with ease, and they can be recovered from the fetus after just a few minutes. Animal experiments investigating the effects of cannabis consumption during pregnancy have produced varying results. A major study of 12,000 women, 11 percent of whom used marijuana, found shorter gestation periods, longer deliveries, lower birthweights and a higher rate of deformities (Hollister 1986; WHO 1997). However, the impact of cannabis on birthweight is minor compared to the effect of cigarette smoking during pregnancy. Apart from these physical aspects, the possibility cannot be excluded that cannabis may affect the behavior and cognitive functions (e. g. learning ability) of the child. Accordingly, the use of cannabis during pregnancy should be restricted as systematically as the consumption of alcohol and smoking (Hagers Handbuch [...] 1992; Hollister 1986).

2.3.7.5 Effects on the immune system

Animal experiments and cell cultures have shown cannabinoids to affect B and T lymphocytes (e. g. increased susceptibility to infection), although these effects were not pronounced, were fully reversible, and were induced only by very high concentrations in excess of those used by individuals to achieve psychotropic effects (Adams, Martin 1996; Hollister 1986; WHO 1997).

The human immune system is relatively resistant to the immunosuppressive effects of the cannabinoids, and the research carried out so far supports the therapeutic use of 9 -THC even in patients whose immune system has been compromised by other diseases (AIDS, cancer).

Literature

Abood ME, Martin BR (1996). Molecular neurobiology of the cannabinoid receptor, Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 39, 197- 221.

Aceto MD, Scates SM et al (1995). Cannabinoid- precipitated withdrawal by the selective cannabinoid receptor antagonist SR 141716A, Europ. J. Pharmacol. 282, R1- R2.

Adams IB, Martin BR (1996). Cannabis: pharmacology and toxicology in animals and humans, Addiction 91( 11), 1585- 1614.

Agurell S, Halldin M et al (1986). Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of 9 -tetrahydrocannabinol and other cannabinoids with emphasis on man, Pharm. Rev. 38( 1), 21- 43.

Axelrod J, Felder CC (1998). Cannabinoid receptors and their endogenous agonist, anandamide, Neurochem. Res. 23( 5), 575- 581.

Beardsley PM, Balster RL et al (1986). Dependence on tetrahydrocannabinol in rhesus monkeys, J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 239( 2), 311- 319.

Bidaut- Russel M, Devane WA et al (1990). Cannabinoid receptors and modulation of cyclic AMP accumulation in the rat brain, J. Neurochem. 55, 21- 26.

Cochetto DM, Owens SM et al (1981). Relationship between plasma delta- 9- tetrahydrocannabinol concentration and pharmacological effects in man, Psychopharmacology 75, 158- 164.

Devane WA, Dysarz FA et al (1988). Determination and characterization of a cannabinoid receptor in rat brain, Mol. Pharmacol. 34, 605- 613.

Devane WA, Hanus L et al (1992). Isolation and structure of a brain constituent that binds to the cannabinoid receptor, Science 258, 1946- 1949.

Dewey WL, Martin BR et al (1984) Cannabinoid stereoisomers: Pharmacological effects, 317- 326. In: Smith, DF (ed.), Handbook of Stereoisomers: Drugs in psychopharmacology, CRC Press, Boca Raton.

Dewey WL (1986). Cannabinoid Pharmacology, Pharmacol. Rev. 38( 2), 151- 178. Di Marzo V, Fontana A et al (1994). Formation and inactivation of endogenous cannabinoid anandamide in central neurons, Nature 372, 686- 691.

Fankhauser M (1996). Haschisch als Medikament, inaugural dissertation, University of Berne, Berne. Geschwinde Th (1996). Rauschdrogen: Marktformen und Wirkungsweisen, 3rd edition. Springer Verlag, Berlin.

Ghodse H (1996). Harmful caution. Comments on Hall et al's ”The health and psychological consequences of cannabis use”, Addiction 91( 6), 759- 773.

Goani Y, Mechoulam R (1964). Isolation, structure and partial synthesis of an active constituent of hashish, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 86, 1646- 1647.

Hagers Handbuch der Pharmazeutischen Praxis (1992). Cannabis monograph, 5th edition. Springer, Berlin.

Hall W, Solowij N et al (1994). The health and psychological consequences of cannabis use, Australian National Drug Strategy, Monograph No. 25, Sydney.

Hanus L, Gopher A et al (1993). Two new unsaturated fatty acid ethanolamides in the brain that bind to the cannabinoid receptor, J. Med. Chem. 36, 3032- 3034.

Hollister LE (1986). Health aspects of cannabis, Pharmacol. Rev. 38( 1), 1- 20. Howlett AC, Fleming RM (1984). Cannabinoid inhibition of adenylate cyclase: Pharmacology of the response in neuroblastoma cell membranes, Mol. Pharmacol. 26, 532- 538.

Howlett AC, Qualy JM et al (1986). Involvement of G i in the inhibition of adenylate cyclase by cannabimimetic drugs, Mol. Pharmacol. 29, 307- 313.

Huw T (1993). Psychiatric symptoms in cannabis users, British J. Psychiatry 163, 141- 149. Iten PX (1994). Fahren unter Drogen- oder Medikamenteneinfluss, Institute for Forensic Medicine, University of Zurich.

Julien RM (1997). Drogen und Psychopharmaka, Spektrum Verlag, Heidelberg. Kleiber D, Soellner R et al (1997). Cannabiskonsum in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland: Entwicklungsfaktoren, Konsummuster und Einflussfaktoren, Berlin.

26 Lehmann Th (1995). Chemische Profilierung von Cannabis sativa L., inaugural dissertation, University of Berne, Berne.

Matsuda LA, Lolait SJ et al (1990). Structure of a cannabinoid receptor and functional expression of the cloned cDNA, Nature 346, 561- 564.

Maykut MO (1985). Health consequences of acute and chronic marihuana use, Prog. NeuroPsychopharmacol. and Biol. Psychiat. 9( 3), 209- 238.

Rodriguez de Fonseca F, Gorriti MA et al (1994). Downregulation of rat brain cannabinoid binding sites after chronic ### 9 -tetrahydrocannabinol treatment, Pharm. Biochem. Behav. 47, 33- 40.

Wall ME, Sadler BM et al (1983). Metabolism, disposition, and kinetics of delta- 9- tetrahydrocannabinol in men and women, Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 34( 3), 352- 363.

Westlake TM, Howlett AC et al (1991). Chronic exposure to 9 -tetrahydrocannabinol fails to irreversibly alter brain cannabinoid receptors, Brain Res. 544, 145- 149.

Wiesbeck GA, Schuckit MA et al (1996). An evaluation of the history of a marijuana withdrawal syndrome in a large population, Addiction 91( 10), 1469- 1478.

Official reports and publications

Kleiber D, Kovar K- A (1998). Auswirkungen des Cannabiskonsums, Expertise zu pharmakologischen und psychosozialen Konsequenzen, commissioned by the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health.

Roques B (1998). Problèmes posés par la dangerosité des ”drogues”, report to the Secretary of State for Health, France.

House of Lords, United Kingdom (1998). Select Committee on Science and Technology, Ninth Report. Hall W, Solowij N (1998). Adverse effects of cannabis / National Drug and Alcohol Research Center, University of New South Wales, Sydney 2052, Australia / The Lancet 352.

World Health Organization (1997). Cannabis: a health perspective and research agenda.

2. Cannabis in Switzerland: The current situation 2.4 Historical and sociocultural aspects

2.4 Historical and sociocultural aspects

Hemp is an old crop that has been used by man for centuries in many and varied ways. It was native to Switzerland for hundreds of years, and in fact was indispensable in many areas of agriculture and for commercial and industrial products. This background has largely been forgotten since hemp developed a stigma as a "narcotic substance" in the 1920s. During the 1960s and 70s, this very versatile traditional fibrous plant was increasingly perceived as nothing more than a substance capable of inducing hallucinations and other abnormal states of mind – worshipped by a minority and rejected categorically by the majority. It was only recently that the image of hemp has been rehabilitated through awareness that it is a renewable raw material with many ecological advantages. However, the contradiction between two apparently irreconcilable components persists: hemp as a valuable and ecologically friendly crop on the one hand, and cannabis as an exotic drug on the other. Sources date cannabis as one of the oldest and most widely cultivated crops in the world (Katalyse Institut 1995; Herer 1993). It had an enormous range of uses (Katalyse Institut 1995; Scheerer 1989). In China, for example, it was used 6,000 years ago to make food, clothing, fishing nets, oil and medicines (Scheerer 1989; Emboden 1982). Cannabis spread from central Asia and subsequently featured in all the cultures in the Middle East, Asia Minor, India, China, Japan, Europe and Africa. Hemp was introduced to the American continent by Spanish seafarers in 1545; the English later brought their European knowledge to the colonies (Katalyse Institut 1995). The hemp plant was used widely to provide fiber and oil and was processed into food and medicines; its consciuosness- altering properties were used both in religious rituals and on an everyday basis (Herer 1993). At a slightly later date hemp was used to make paper: China started in the 1st century BC, Europe around 1200. At the end of the 19th century, 75 percent of all the paper produced in the world was made from hemp (Bröckers 1988). This varied and widespread use – hemp growing was made compulsory in some parts of America in the 17th and 18th centuries – is contrasted starkly with the decline of cannabis from the 19th century onward (Katalyse- Institut 1995). Hemp cultivation was still pursued in the early part of the industrial era in continental Europe, but competition from Russia was already having a serious impact, and cotton imports were increasingly destroying the market for hemp fiber. In western Europe more and more arable land was given over to cereals and animal fodder (Bischof 1994). In Switzerland, hemp was grown for domestic use only from the mid- 19th century, and by the start of the 20th century it had practically disappeared from the landscape. Many authors in the 19th and 20th centuries lamented the decline of hemp cultivation, blaming it on the population's lack of diligence and inadequate processing methods. Social and agrarian reformers praised hemp as a possible source of income for the impoverished classes. It is particularly clear from the writings of the time that hemp cultivation was seen as a means of underpinning a traditional way of life and values, and was thus thought to have a stabilizing function. In Germany, too, hemp cultivation started to decline before the First World War, although interest surged again during both World Wars since Germany was largely cut off from the world fiber market and was dependent on hemp to meet its needs (Katalyse Institut 1995). An interesting feature in this connection is the "jolly hemp book" issued by the National Socialists, which portrayed hemp as a reliable native raw material indispensable in industry and the home. But America also stylized hemp as the savior of the nation, not least in a hemp propaganda film entitled "Hemp for Victory" (Bröckers 1988). In Switzerland, a "cultivation campaign" was announced in 1940 under the auspices of Federal Councilor Wahlen; the objective was also to promote the production of hemp, although the area under cultivation was in fact small (Tobler 1950). After the Second World War hemp fibers were replaced by synthetic fibers, hemp oil by mineral oil, lamplight by electric light. Synthetic drugs proved to be more effective than cannabis, the petrochemical industry obviated the need for hemp as a pressing material, and wood fiber replaced hemp in paper manufacture. The significance of this once indispensable source of fiber declined in the face of the difficulties associated with mechanizing the harvesting and processing of the plant (Tobler 1950). It was by no means chance that the materials competing against hemp were easy to integrate into the industrialization process. One of the aims of competitors was most certainly to stigmatize hemp. The economic decline of hemp was accompanied by an increase in prohibition worldwide. After the interwar period, hashish, marijuana and people who used these substances were increasingly criminalized. In the 1930s the American timber industry sponsored a financially motivated campaign against marijuana, culminating in 1937 in the passing of the Marijuana Tax Act in the USA (Scheerer 1989). Before this, in 1925, the Second Opium Conference had placed hashish on a controlled list of narcotic substances. In 1929 it became illegal under German law to trade in or use "Indian hemp and more specifically its resin" (Katalyse Institut 1995); Switzerland followed in 1951, incorporating a ban into its amendment of the Swiss Narcotics Act (Länzlinger 1997). The point at which cannabis also started to be used in central Europe as a hallucinogen, and the extent to which it has been used, is still unclear (Scheerer 1989). Scheerer claims that the overriding purpose of hemp cultivation in this geographical region has always been to provide fibers and oil (Scheerer 1989). This view is upheld by Swiss sources from the 19th and 20th centuries. Descriptions of Swiss agriculture portray hemp as a source of fibrous raw material which was processed mainly into textiles. Some sources mention that the plant emitted an intoxicating odor, although this was in no case perceived as dangerous. It was known that a different type of hemp, Cannabis indica, with narcotic properties existed in the "Orient", but the native species, Cannabis sativa, was not associated with such effects. The use of the plant as a hallucinogenic, mind- altering substance was considered as behavior typical of "Orientals". This perception resulted from a general trend of the era: since the 18th century, the Orient had been perceived as the incarnation of everything that was "different" from the west, as an alternative to the sober rationality of the "Occident" that stimulated the western imagination. In the early 20th century the Pharmacological Institute in Berne carried out a series of experiments which showed that the effects of Cannabis sativa and Cannabis indica were certainly comparable, but this finding did not give rise to any concern. The native plant seemed to be safe from "abuse". Hemp was also used in Europe and America for medicinal purposes; this aspect will be considered in Chapter 2.5. If we consider the typology of cannabis users at various points in time, we find that cannabis has been, and continues to be, used by very different groups for different purposes. For a long time, hemp was associated with the poor; those who couldn't afford tobacco smoked hemp (Kessler 1984). Solidarity within a subculture and working and smoking together were elements important to those who used hemp (Tanner 1996); hemp was an expression of a traditional way of life which may also have been viewed as a form of resistance against the imperatives of economic modernization and commercialization. In the 1840s, the Club des Hachichins in Paris embodied the use of hemp, associated with an alternative, oriental culture, as a positive contrast to the regular, bourgeois way of life. This gave hemp a new image; it was no longer seen as a way of upholding tradition but as rejection of normality. The narcotic substance decried by regular citizens was thought to transport users to a new level of consciousness and perception and to stimulate artistic productivity (Tanner 1996). In this way the Bohemians' defense of hemp involuntarily provided the arguments that were used to make the "drug" taboo, although this was by no means their intention (Rudgley 1993). The users of the substance at the time formed a relatively homogeneous group, although subsequently the group came to be larger, heterogeneous and difficult to define (Bröckers 1988). The criminalization of cannabis in Switzerland from 1951 did not have the desired effect. With hindsight, it is much more likely to have contributed to making the plant and its use into a symbol of peace and tolerance. The stigmatization of cannabis served to highlight its existence and to popularize it in subcultural settings (v. Wolffersdorff- Ehlert 1989). The use of cannabis was initially centered on the so- called beat generation and was not particularly widespread (v. Wolffersdorff- Ehlert 1989); from about 1964 it became more common in industrial countries, reaching its first high point in the legendary "summer of love" in 1967. In Switzerland there has been a marked increase in the number of offenses involving narcotic substances since 1970, although this was probably due more to the low level of tolerance by the police and the courts than to a sudden surge in consumption. The media reported a "wave of drugs" said to be submerging the country. A "war" or "crusade" was mounted against the dangerous substances in an attempt to kill demand, but the number of users increased unabated. Harder drugs such as heroin and cocaine started to make more of an appearance, and from about 1974 the focus shifted away from hashish users to people dependent on hard drugs and "drug fatalities". Cannabis use expanded into a mass phenomenon in the shadow of this new focus. However, this more widespread consumption also gave rise to a tendency for people to individualize their use of cannabis in order to forget their personal frustrations, leaving the collective experiment behind them (v. Wolffersdorff- Ehlert 1989). The consumption of hemp, although outlawed in 1975, has normalized and become a commercial proposition, resulting in a growing disparity between the legal norm and judicial practice. Twenty years ago, using cannabis products was exotic and something of an adventure for the adolescents of the day, but in recent years it has become almost normal for many of them. Today young people of 14 can talk quite openly among themselves or with trusted adults about their drug use, and those who do not use cannabis, for example, are tolerant of occasional smokers. It is interesting to note that the use of various drugs is determined to a very large extent by the habits of the group that is currently "in" (which may be a school or an entire suburb, or people involved in a certain type of sport). Trends of this type are open to very little intervention on the part of parents or guardians. Years ago there was still a clear distinction between adolescents who drank alcohol and those who smoked cannabis, with the two groups generally having little to do with each other. This distinction has blurred increasingly. The single- substance "cultures" still exist of course, but many adolescents consume both alcohol and cannabis depending on the situation and availability. This intermingling of two formerly separate "cultures" is increasingly rendering obsolete the question of the extent to which cannabis consumption is open to social integration. In the current situation, cannabis has become an integral part of the social reality of a not inconsiderable part of the population. Cannabis use has changed from something originally intended to achieve a "high" and a particular emotional state into a recreational activity pursued purely for the pleasure of it. Against this background, it is difficult for people who consume a small amount of cannabis for relaxation purposes – in the same way that social drinkers consume alcohol – to understand why cannabis is referred to as a narcotic drug. As with any psychoactive substance, of course, there are adolescents and adults who seek refuge from the reality of a situation which, for them, is intolerable. It is this group which deserves special attention. On the other hand, there is a current resurgence of interest in hemp as a renewable raw material, and many traditional uses for the plant have been rediscovered. Cannabis is once again being used in medicine, with some success (the therapeutic use of cannabis is described in detail in Chapter 2.5). The ecological advantages of hemp are particularly evident in comparison with cotton, a crop which is susceptible to insect pests and thus contains pesticide residues (Katalyse- Institut 1995), but also in comparison with wood because hemp grows much faster. Switzerland now has a hemp support project run by the Federal Office of Agriculture (Bischof 1994). This project threw into sudden and sharp focus the traditions and expertise which had been lost with the demise of hemp cultivation. Seeds had to be imported from Hungary and France, and the techniques for growing the plant had to be relearnt (Bischof 1994). Overall there is growing interest in hemp cultivation and products made from hemp.

Literature

Bischof A (1994). Mörderkraut [Murderous weed]. In: Tagesanzeiger Magazin, 37, 28- 37. Bröckers M (1988). Hanfdampf und seine Kriegsgewinnler. Kleine Kulturgeschichte der nützlichsten Pflanze der Welt. In: Transatlantik 3, 44- 53.

Emboden W A (1982). Cannabis in Ostasien. Herkunft, Wanderung und Gebrauch. In: Völger G / von Welck K (ed.), Rausch und Realität. Drogen im Kulturvergleich, 3 volumes, rororo, Reinbek bei Hamburg, 557- 566.

Fankhauser M (1996). Haschisch als Medikament, Berne (unpublished dissertation manuscript). Herer J (1993). Die Wiederentdeckung der Nutzpflanze Hanf; Cannabis, Marihuana, Zweitausendeins, Frankfurt am Main.

Katalyse- Institut für angewandte Umweltforschung (ed.) (1995). Hanf & Co. Die Renaissance der heimischen Faserpflanzen, Die Werkstatt, Göttingen.

Kessler Th (1984). Hanf in der Schweiz , Nachtschatten, Grenchen. Länzlinger S (1997). Raunen, Reden, Regulierung. Die Geschichte der schweizerischen Betäubungsmittelgesetzgebung bis 1951, Zurich (unpublished manuscript for Lizentiat dissertation).

Rudgley R (1993). The alchemy of culture. Intoxicants in society, British Museum Press, London. Scheerer S (1989). Cannabis: Herkunft und Verbreitung. In: Sebastian Scheerer/ Irmgard Vogt (ed.), Drogen und Drogenpolitik. Ein Handbuch, Campus, Frankfurt am Main, 387- 373.

Tanner J (1996). Rauchzeichen. Zur Geschichte von Tabak und Hanf. In: Christoph Maria Merki/ Thomas Hengartner (ed.), Tabakfragen. Rauchen aus kulturwissenschaftlicher Sicht, Chronos, Zurich, 15 - 42.

Tobler F (1950). Der Stand des Flachs- und Hanfanbaus in der Schweiz , St. Gallen. von Wolffersdorff- Ehlert Ch (1989). Cannabis: Die Cannabis- Szenen. In: Sebastian Scheerer /Irmgard Vogt (ed.), Drogen und Drogenpolitik. Ein Handbuch, Campus, Frankfurt am Main, 373- 378.

2. Cannabis in Switzerland: The current situation 2.5 The medical importance of cannabis

2.5 The medical importance of cannabis

Note on this chapter: This report is concerned primarily with the use of cannabis as a recreational drug. Whether cannabis products can be used beneficially in the medical treatment of patients is a completely different question which must be considered separately from both a technical and a legal point of view. However, Chapter 2.5.2 provides a brief summary of the current state of knowledge, and the conclusions at the end of this report will also touch on this aspect. The paragraphs printed in italics and smaller typeface are intended for those with a special interest in this field and may be omitted without fear of losing the context.

The first written evidence of cannabis being used in medicine is probably a Chinese handbook of botany and healing some 4,700 years old. Cannabis was mentioned in herbals from the 16th century. It was used in popular medicine from the time of the first crusade and featured in the medicine practiced by monks in many monasteries. It was used to treat rheumatic and bronchial disorders, and was also prescribed generally as a substitute for opium. In the 19th century it was also a popular treatment for migraine, neuralgia, epileptiform convulsions, insomnia and other conditions. Marijuana was the most commonly used pain killer in America until 1898, when it was faced with stiff competition from Aspirin and was ultimately replaced by a wide range of new, synthetic medications. Between 1842 and 1900, cannabis preparations accounted for half of all medicines sold in America (Herer 1993). More than 100 different cannabis- based medicines were available in Europe, most of them in Switzerland as well, between 1850 and 1950 (Fankhauser 1996). Difficulty in dosing these preparations, paradoxical effects and the development of more effective products led to a decline in prescriptions for cannabis even before prohibition finally put an end to its use (Mikuriya 1973, Mikuriya 1982, Springer 1982). Today doctors are not allowed to prescribe cannabis or cannabinoids (the legal situation is explained in Chapter 2.6.4.3). Scientific research involving cannabis requires a special license from the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health. The Paraplegic Center in Basel is currently running a study to investigate dronabinol in the treatment of painful muscle spasms in paraplegics; initial results are promising.

Below is a brief summary of two medical aspects of cannabis:

- A review of the major scientific findings relating to the therapeutic use of cannabis ( 9 tetrahydrocannabinol [THC] and synthetic cannabis products);

- An overview of medical experience with cannabis poisoning in acute medical care.

2.5.2 Investigation of the therapeutic action of cannabis

In recent years, the prescription of cannabis and cannabis- based active principles for therapeutic purposes has become a recurrent and growing focus of scientific, medical and political interest. Some countries permit cannabis to be prescribed under various conditions, usually for medical trials or on a named- patient basis; a treatment regimen for a distinct indication has been established only in very few cases. The only indications for which dronabinol (delta- 9- THC) has received regulatory approval for routine use to date are to stimulate appetite in AIDS patients and to control nausea and vomiting in patients undergoing chemotherapy in whom other drugs have proven ineffective. Dronabinol was launched in the USA in 1986 under the name Marinol and has since been approved in Canada (1990), Australia (1995), Israel and South Africa. It is available for license in Germany, Belgium, Japan and Switzerland (Kleiner and Kovar 1998).

In 1997 the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in the USA reviewed the available literature on the therapeutic value of cannabis and the need for further research. The information below is based on the expert report subsequently submitted to the NIH (Beaver et al 1997). A further summary has been complied by Gowing et al (1998).

Pain management: Two controlled studies of patients with cancer pain were carried out with oral THC vs. placebo. Although THC had an analgesic effect, it was difficult to dose because of the very narrow therapeutic window between ineffective underdosing and the adverse effects associated with overdosage. No studies have been carried out with smoked or otherwise inhaled cannabis.

Neurological disorders: There is evidence that cannabis is effective against the spasticity associated with multiple sclerosis and has a certain potential in the treatment of epilepsy, but no clinical studies have been carried out in either indication. Cannabis has proved ineffective in attempts to treat Parkinson's disease and Huntington's disease.

Nausea and vomiting caused by chemotherapy in cancer patients: THC administered orally is more effective than placebo but less effective than drugs such as metoclopramide. The relative efficacy of oral THC or smoked marijuana compared with newer anti- emetics has not been studied. Dronabinol is authorized in the USA for patients in whom conventional therapy to counter nausea and vomiting is ineffective.

Glaucoma: Local administration of THC reduces intraocular pressure in healthy subjects and glaucoma patients without affecting blood pressure or mood. The mechanism of action is unknown.

Cachexia (wasting associated with serious illness): Clinical studies have demonstrated a connection between cannabis use and increased appetite in healthy subjects. THC can bring about weight gain in wasted AIDS and cancer patients. Dronabinol is approved in the US for the treatment of AIDS- related anorexia.

Further research is recommended in all these indications. In particular, controlled clinical trials are needed which focus both on pharmaceutical products and on smoked cannabis.

2.5.3 Cannabis poisoning in medical emergency statistics

A completely different aspect of any medical evaluation of cannabis must be the experience gained with acute intoxications encountered in critical care situations. There are no systematic medical statistics documenting cases of acute poisoning and their outcome, but the figures compiled by the Swiss Toxicology Information Center and studies carried out by two hospital emergency departments (Berne and St. Gallen) provide a good indication of the current situation.

2.5.3.1 Swiss Toxicology Information Center

In 1997 the Swiss Toxicology Information Center handled 87 enquiries about cannabis poisoning (66 in 1996 and 60 in 1995). Between 70 and 75 percent of these cases involved simple intoxication with cannabis, between 25 and 30 percent involved another substance as well. Of the enquiries received, 60 percent came from doctors, 40 percent from lay people. More detailed analysis only started in 1997. Of the cases of simple intoxication, two had an asymptomatic course, eight involved moderately severe symptoms and one involved severe symptoms. All the patients survived.

2.5.3.2 Clinical trials in Switzerland

a) Study in Berne

A retrospective study analyzed all the cases of acute intoxication with illegal drugs admitted to the emergency department of the Inselspital Hospital in Berne during a 183- day period in 1989 and 1990. The study covered a total of 157 patients, among whom cannabis featured fewer than four times (< 1.6 percent) in combination with another substance. A total of 257 different substances were recorded for these patients. Cannabis showed no dangerous effects in this study.

b) Study in St. Gallen

A five- year prospective study (1993 - 1997) of 20,220 medical emergencies at St. Gallen cantonal hospital showed that intoxication with cannabis alone accounted for just three emergencies. This is equivalent to 0.015 percent of all medical emergencies. All three patients presented to the out- patients department with mild mental disturbances. The symptoms regressed spontaneously within a short time in all patients. Cannabis was detected in a total of 21 patients (0. 1 percent of all medical emergencies), three times as the sole cause of poisoning, once in combination with other illegal drugs, and 14 times in combination with illegal drugs, prescribed medication and alcohol. There were no deaths or serious complications related to cannabis.

Literature

Beaver WT, Buring J et al (1997) : Workshop on the medical utility of marijuana. Report to the Director, National Institutes of Health, by the Ad Hoc Group of Experts

British Medical Association (1997). Therapeutic use of cannabis, HAP. Hall W, Solowij N et al (1995). National Drug and Alcohol Research Center, Monograph Series No. 25, Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra.

Fankhauser M (1996). Haschisch als Medikament. Dissertation, University of Berne. Gowing LR, Ali RL et al (1998): Commentary. Therapeutic use of cannabis: clarifying the debate. Drug and Alcohol Review 17: 445- 452.

Herer J (1993). Die Wiederentdeckung der Nutzpflanze Hanf; Cannabis, Marihuana, Zweitausendeins, Frankfurt am Main.

House of Lords/ Subcommittee on Cannabis (1998). Cannabis: the scientific evidence and medical evidence. Science and Technology, Ninth Report.

Kleiber D, Kovar KA (1997). Auswirkungen des Cannabiskonsums. Eine Expertise zu pharmakologischen und psycho- sozialen Konsequenzen. Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft, Stuttgart.

Mikuriya TH (ed.) (1973) : Marijuana. Medical papers, 1839- 1972. Oakland, California. Mikuriya TH (1982) : Die Bedeutung des Cannabis in der Geschichte der Medizin. In: Burian W, Eisenbach- Stangl I (ed.) Haschisch: Prohibition oder Legalisierung. Beltz, Weinheim.

Roques B, (May 1998). Problèmes posés par la dangerosité des ”drogues”, Report to the Secretary of State for Health, France.

Springer A (1982). Zur Kultur- und Zeitgeschichte des Cannabis. In: Burian W, Eisenbach- Stangl I (ed.) Haschisch: Prohibition oder Legalisierung. Beltz, Weinheim.

Source for St. Gallen study: Stillhard U. Akute Intoxikationen mit illegalen Drogen am Kantonsspital St. Gallen von 1993 bis 1997: Veränderungen in der Demographie und im Verlauf. Dissertation at the Faculty of Medicine, University of Basel, 1998.

2. Cannabis in Switzerland: The current situation 2.6 The legal environment

2.6.1 International conventions

A significant factor in the policy debate over cannabis – as is also true in the case of other substances classified as narcotic drugs – is the fact that the scope for national legislation is curtailed to some extent by obligations entered into under various international agreements (for a complete and exhaustive account of international drug law see Rausch 1991: page 107 to 136). Several conventions have been drawn up in order to regulate the abuse and trafficking of illegal substances. These international conventions have been ratified by numerous countries and to some extent shape their national legislation directly. Among the matters covered by these conventions is cannabis consumption. A milestone in the development of international drugs law was the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs of 1961. This laid down rules of international application and largely superseded a number of existing conventions, agreements and protocols which were incomplete in their coverage. To this day the Single Convention forms the cornerstone of most countries’ national drugs legislation. It requires ratifying States to promulgate laws giving effect within their territories to the measures recommended in the Convention (HugBeeli 1995: page 146). The Single Convention places cannabis and cannabis resin in the same category as opiates (e. g. heroin), in Schedule IV. It classifies substances hierarchically according to their medical utility and carries on a distinction between the useful substances of the West (medicines) and traditional substances of the Orient having no therapeutic value (Richard 1995: page 18). However, with the emergence of new, chemically manufactured substances in the seventies the Single Convention soon began to appear outdated. As a consequence, a new international agreement was adopted to cover these new synthetic products. This was the Convention on Psychotropic Substances of 1971, also known as the Vienna Convention. It places synthetic products in the category of 'psychotropic substances’ (psychopharmaceuticals, barbiturates, LSD). The Convention permits their use in medicine but otherwise prohibits consumption. 1 The main active constituent of cannabis (delta- 9tetrahydrocannabinol) is included among the stimulants (e. g. amphetamine) in Table II (psychotropic substances), which means it is subject to the same level of controls as narcotic drugs under the Single Convention. The residual mix of active ingredients in cannabis, on the other hand, is included in Table I under hallucinogens, which may be used solely for scientific and – to a limited degree – medicinal purposes under individual licenses issued by the authorities. In 1972 there followed the Protocol Amending the Single Convention, which defines the functions of the International Narcotics Control Board. This body works in cooperation with governments to ensure that only such quantities of narcotic drugs are cultivated, produced or used as are necessary for medicinal and scientific purposes (Hug- Beeli 1995: page 147). The most recent convention is the United Nations Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances 2 of 1988, which further extends the scope of international drugs law. Unlike the Single Convention and the Vienna Convention, 3 this convention expressly requires signatory countries to prohibit the activities preparatory to personal consumption. It does not require the actual consumption of illegal substances to be made an offence, only their possession and procurement (Hug- Beeli 1995: page 148). The Convention permits these substances to be used in medicine but otherwise prohibits all consumption.

2.6.2 The Federal Narcotics and Psychotropic Substances Act (BetmG; SR 812.121)

The Federal Narcotics and Psychotropic Substances Act (BetmG) of 1951, as amended in 1974, regulates the production, distribution, purchase and use of narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances which are subject to State controls. Within the meaning of the law, narcotic drugs include addictive substances and compounds of the cannabinoid type (Article 1( 1) BetmG). By way of example, in the second paragraph of the same Article, hemp is specified as a raw material of narcotic drugs. The resin of the glandular hair of the hemp plant (known as 'hashish’) is also listed as an active constituent of cannabis. Under Article 8( 1) BetmG, neither hemp plants used for the purpose of producing narcotic drugs nor hashish may be cultivated, imported, produced or placed on the market. Hemp may be freely cultivated for other purposes, however, without any special permit being required. Article 4 BetmG, which provides that a permit is required for the production of narcotic substances, does not apply in the case of hemp. 5 . Under Article 1( 2) c and d BetmG, narcotic substances also include 'other substances’ having a similar effect to hemp or the resin of its glandular hair and 'preparations’ containing any of the 'substances’ already mentioned. Hemp products are thus by definition narcotic substances. Whether Article 8( 1) d BetmG actually extends the criterion of narcotics production to hemp products ['the following narcotic substances may not be cultivated, imported, produced or placed on the market: d) hemp for the purpose of narcotics production or the resin of its glandular hair (hashish) ’] is an open question, which has not yet been definitively resolved by the courts. The current position therefore appears to be that the production and supply of cannabis products such as cannabis oil etc. are not subject to any restriction whatsoever under the drugs legislation unless the motive is the production of narcotic drugs (see Annex d to the Order of the Federal Office for Public Health on Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances, BetmV- BAG, SR 812.121.1). Under the first subparagraph of Article 19( 1) BetmG it is a criminal offence to cultivate hemp without authorization, where it is done for the purpose of producing narcotic drugs. Otherwise, the penal provisions of the BetmG draw no distinction between cannabis and the other narcotic drugs and make both illicit trafficking and consumption an offence. Since the decision of the Swiss Federal Supreme Court of 29 August 1991, 6 the legal position is that, according to the present state of knowledge, cannabis, even in large quantities, 'cannot endanger the health of many individuals’ within the meaning of Article 19( 2) a BetmG. Any offence contrary to the first subparagraph of Article 19( 1) BetmG, which concerns cannabis, cannot therefore be treated as 'a serious case’ within the meaning of Article 19( 2) a BetmG. Trafficking in cannabis products, unlike other drugs such as LSD, heroin or cocaine, is thus capable of being treated as a 'serious case’ (carrying a minimum sentence upon conviction of one year’s imprisonment) only if it is organized by a gang or carried on as a business. The consumption of hashish, however, will not automatically be treated as a 'minor case’ in accordance with Article 19a( 2) BetmG. It cannot be treated as such in the case of somebody who is a regular user of hashish and has no intention of changing this behavior. 7 For minor offences of cannabis trafficking and consumption the approach varies from canton to canton. 8 The courts have been tending to take a more lenient approach to sentencing for offences of personal consumption. In some cantons there are even places (meeting points, small venues) where cannabis is freely consumed or sold in small quantities. Ten of the 26 cantons also confirm that their police forces adopt a different approach to drug law enforcement where cannabis is concerned, as opposed to other illegal substances, and tend to turn a blind eye to consumption offences (see Fahrenkrug et al 1995: page 143). According to the results of special surveys carried out by the Swiss Federal Statistical Office 9 of court decisions 10 in drugs cases in the years 1991 and 1994, cannabis products were the substances most frequently involved in convictions for drug use, especially where the person before the court was a minor (in 95 percent (1991) and 91 percent (1994) of cases where a minor was convicted on a drugs charge). These rates fall to 65 percent and 51 percent in the case of adults. In cases where no criminal conviction is entered in the records, the most common court orders against persons convicted of mere consumption of cannabis are fines, followed by censures or cautions.

2.6.3 The Swiss Road Traffic Act