I A Background History of Drugs

| Books - Society and Drugs |

Drug Abuse

Our purpose is to set forth the major events which constitute the ac-cessible history of those mind-altering drugs popularly used prior to our own time. We hope that such a history—one emphasizing social features of use whenever possible—will help create a perspective from which to view the contemporary phenomenon in our own society of widespread and expanding use of mind-altering drugs, which is often coupled with intense interest and emotion. In setting out to conduct this historical review, we expected to find certain principles operating —ones which would help us to understand how drugs come to be adopted for use, in what ways, and by what groups. We also looked for regularities from society to society or era to era in means or cir-cumstances under which drug use would be reduced or constraints would be placed upon particular kinds of conduct emerging as drug effects. Concern with prohibitions leads to an assessment of social reactions to drugs and the judgments placed on drug effects and styles of drug use. In today's parlance this becomes a matter of drug abuse or of a society's having a drug problem.

In our purposes and expectations we have been disappointed—perhaps we should even say we have failed. Yet, in each instance we have also been pleased by small achievements which have been at least way stations on the road to a perspective. Our failures rest upon the limitations in ourselves and our enterprise. We shall be explicit about those of which we are aware.

The greatest limitation is the absence of artifacts, seeds, docu-ments, and observations which constitute the subject matter of history or prehistory itself. Secondarily, with a few notable exceptions, there is an absence of historical studies as such. Up until the nineteenth century, not a great deal had been said about psychoactive drugs, either by those who had tried them or by those who had observed others using them. As for epidemiology, clinical reports, or social-problem analyses, these were not topics for even the most perceptive writers until after the Reformation and the subsequent advance in science had produced a social awareness which—with industrialization —gave rise to public-health endeavors (Dubos, 1959). Early medicine and pharmacology are exceptions to this rule of general disinterest, for the healers have long had an interest in drugs and their effects. In the first century A.D., Dioscorides, whose text was the leading one in phar-macology for sixteen centuries, wrote of the poppy both as a medica-tion (". . . a pain easer, a sleep causer, a digester, helping coughes and coelicacall affections") and as a danger (". . . being drank too much ithorts, making men lethargicall and it kills"). But this only tells us that the poppy was employed in folk medicine—a popular utilization, to be sure; it does not tell us how widely the poppy was used or how many of which groups of patients were most likely to succumb to effects "lethargicall" or killing.

What are scarce data in the written literature are reduced to inference in prehistory. We know that early Anatolian beakers were constructed with a sieve at the bottom and straw-like tubes outside and that a more sophisticated version of a similar pot, seen in early dynastic Egyptian painting-s, used real straws and a separate strainer. From these artifacts is deduced the presence of a yeasty, high-in-protein beer. When it was first introduced is unknown—possibly around the beginning of agricultural settlements qua villages, such as Beidha, Jarmo, Catal Hiiyiik, and similar centers—which would give dates within 7000 B.c. Some archaeological evidence to support such an early date for beer has been found (Mellaart, 1967) and the circum-stances of life were such that these people could easily learn brewing.

Paleoethnobotanists (Helbaek, 1961) have found berry stones and seeds from a 2000 B.c. Alpine site—wine-making refuse probably, but some say human excrement instead. And when a cannabis seed is found in an ancient place, is it proof of hemp, bird feeding, ancient hashish, or nothing at all? Even eyes of observers disagree; what Kritikos and Papadaki (1963) describe as a poppy on a Minoan vase that proves the ritual use of opium, another may see as a pomegranate dispropor-tionately rendered.

Aside from the difficulties imposed by limited written sources and archaeological finds and by disputes over their interpretation ( What was Homer's "nepenthe" after all?), this review suffers from a limited access to existing materials. In most instances, we have not in-spected primary sources, nor have we covered all the secondary sources, since we have been limited linguistically to French, English, German, and Greek; shortage of time has also restricted us to the most readily available sources. Too, in the interests of space and emphasis, we have been forced to be gross even when refinement was possible. For example, a great deal of work has been done on the recent history of one drug in one region : peyote diffusion among American Indians. Aberle (1966), La Barre (1964 ), and Slotkin (1956) have produced detailed studies but of necessity our reference to their important find-ings is brief.

A further limitation is not of sampling, as above, but of logic. We have sought sequences, patterns, unifying principles, chronologies, and geographies with the hope of making sense out of drug history, not only for its own sake but because we cannot yet make sense out of what we see in our own society's changing drug patterns. We wanted yesterday to inform us about the meaning of today. As a consequence, we have filled in bottomless pits in time, made parallels out of per-pendiculars, discounted incongruity, and elevated rare cases to exem-plary roles. No one intends to be illogical but, considering our purpose and limited data, we cannot but suspect ourselves of this fault for the tendency is to seek, out of understanding, an aesthetic structure, and such structures, while reducing uncertainty, do not always harmonize with the bits and pieces that are the data of the senses.

ASSUMPTIONS AND QUESTIONS

As one inspects the record of events comprising the introduc-tion, adoption, and/or resistance to psychoactive substances, certain features of man and his social and natural environments must be kept in mind. In the first place, one assumes there will be no initiation into any drug use until that substance is physically available. Drug availability is one key to use and that in turn leads to inquiries about agri-culture, commerce, travel, and manufacture (for example, distillation). That assumption, although generally correct, might lead one to ignore magical substances whose pharmaceutical nature is inconsequential (as long as it is inert) but whose symbolic presence is what matters. An example is the placebo, which is found in the past as well as in the present.

It is incorrect to assume that all inefficacious medication, as judged by modern standards of pharmaceutical potency and physiologi-cal effect, was employed magically. Much in ancient medicine thought to have healing properties because evaluative means were inadequate is now known to be ineffective. In the ancient Middle East, for example, opium faced stiff competition from such remedies as eunuch's fat, virgin's urine, burnt frog, and crocodile dung. The Egyptians and some peoples in the Fertile Crescent did try to determine dosage and toxicity by experimenting on slaves and prisoners (Thorwald, 1963) hilt, as late as the sixteenth century in Europe, the "doctrine of signatures" held sway. Accordingly, a plant with heart-shaped leaves was good for heart trouble, one with kidney-shaped pods helped kidneys, and the mandrake root, shaped like a whole man, was deemed a panacea (Dawson, 1929; Gordon, 1949; Grenfel and Hunt, 1899; Haggard, 1929; LaWall, 1927). Modern America is, of course, usually con-sidered advanced over such primitive notions, unless one takes into account the use of tons of unproven home remedies and proprietary over-the-counter nostrums each year. Many will remember the drug industry's outcry against recent Food and Drug Administration pro-posals that drug efficacy be demonstrated scientifically before a product be allowed on the market. They may also recall the rapid acceptance by hippies in 1967 of banana peel as a euphoriant or their use of other inert products (lactose disguised as LSD, for example), even though more potent materials such as LSD and marijuana were avail-able.

Once a substance is available, there must be an opportunity to notice it and to ingest it and, for any kind of learning or repeated dosage, to be able to identify it reliably. Identification leads to ques-tions about environmental discriminations, as in folk medicine and pharmacognosy, to publicity about substances which teaches potential users about availability, identification, and techniques for administra-tion, and to an analysis of the determinants of individual ingestion behavior. The assumption of identification and willful ingestion is again generally correct, but not comprehensive ; it ignores use occurring without awareness or intent. An example of this probably occurred in early man's discovery of accidentally fermented products and in the fortuitous sniffing or tasting of active substances, such as may have happened with the Scythians and cannabis smoke, if Herodotus may be so interpreted, or as occurred—painfully—in the ergotism of St. Anthony's fire, or as happened in Basle in our century when Dr. Hoff-man in casual tasting discovered the effects of LSD-25. Attention to ingestion—whether eating or sniffing—focuses on how ordinary be-havior becomes a vehicle for drug administration; it excludes extraor-dinary behavior which requires that a technique be learned. Here one refers to learning how to smoke—a momentous development in the epidemiology of drug use—or how to inject—also an important event with widespread repercussions. Yet the assumption of intake of any kind—possibly even of absorption (Mexican peasants rub marijuana on their sore joints)—ignores noningestive use. Modern patients have been known to wear prescriptions as amulets (Blum, 1960). Psycho-active mandrake roots were handed down by generations as household ikons from Iceland to Egypt (Thompson, 1934) ; Great Plains Indians hung mescal beans about their necks as fetishes and Zuni priests ap-plied peyote buttons to their eyes to bring rain (La Barre, 1964). Coca leaves were burned as sacrificial offerings by the Incas in pre-Colum-bian times (de Cieza, 1959) and ceremonial rites with cannabis or tobacco—without ingestion—occurred in Africa (Laufer, Hambly, and Linton, 1930). Today, in San Francisco, one may see hippies wearing marijuana in their lapels or LSD cultists offering that drug as a sacrament.

Repeated ingestion and conduct instrumental to that ingestion lead most observers to speak of motives and purposes of such behavior. These are inferences by the observer even if the observer himself is also the doer. These are the common explanations given by men to account for what they do and, as such—no matter how suspicious one may be of either self-awareness or motivation theory—should not be ignored. Anyone interested in drug taking is soon confronted with human intentions as well as with these aims redefined as effects. Thus, one finds over the centuries men seeking—and drugs offering—health, relief of pain, security, mystical revelations, eternal life, the approval of the gods, relaxation, joy, sexuality, restraint, blunting of the senses, es-cape, ecstasy, stimulation, freedom from fatigue, sleep, fertility, the approval of others, clarity of thought, emotional intensity, self-under-standing, self-improvement, power, wealth, degradation, a life phi-losophy, exploitation of others, enjoyment of others, value enhance-ment, and one's own or another's death. Drugs have been employed as tools for achieving perhaps an endless catalogue of motives. One suspects that the statement of intentions is at least an expression of the view of any one man, or of men in any era, of what man is and ought to be and, teleologically, why he busies himself as he does. The cata-logue also suggests that what men say they seek with drugs is also what they say they seek without them.

To attend to motives must not lead the observer to ignore either the uses or consequences of drugs which can hardly be attributed to intentions. Jellinek (1960), for example, describes the syndrome of delta alcoholism as a surprise consequence of drinking over a long period of time even if no apparent psychological factors—such as es-cape or anxiety reduction—are present. The French child who drinks wine regularly from age four or five on because his parents believe water unsafe may discover when he grows up--after the fifteen-or-so years necessary for "incubation" of alcoholism—that he is an alco-holic. Iatrogenic morphine dependency can be similar. A patient is given that drug to relieve pain or he may be given it or a sedative or a strong tranquilizer without choice or the knowledge of what it is—and only when he stops his use does he discover his discomfort. He may also discover, as Lindesmith (1965) once suggested, that others in-struct him in the fact that he is now an addict. The history of the dis-covery of opiate dependency itself reveals how frail the link between intentions and outcome when outcomes themselves are unknown. It was not until the 1700's that we have reports of withdrawal phenom-ena (Sonnedecker, 1958 )' and not until the nineteenth century that physicians were aware of opium's potential for producing physical dependency. Consequently, in a motivational analysis, care must be taken not to confuse specific drug effects with what the user intended, provided he had any effect-related intentions at all. In this regard, one curious but little noted feature is the frequency with which initial ill effects, quite specific to the drug, do not discourage continued ex-perimentation. The first experience with tobacco, alcohol, opiates, peyote, and LSD is often unpleasant, producing nausea or dysphoria or—as is often the case in marijuana smoking—nothing at all. Ap-parently, specific drug effects may play but a small part, at least ini-tially, in the establishment of patterns of use. This paradox is of in-terest to the pharmacologist as much as to the epidemiological historian.

In a different vein, Aberle (1966 ). describes how motives can multiply once drug use begins. Among Navajos the simple reason of curing an ailment accounts for most Indians' initial use of peyote. After-wards, when the investiture in the cult has taken place, peyote becomes, as Aberle says, "polyvalent" : ". . . once people have entered the cult . . . its meaning becomes much more differentiated for them, and its appeals diverse (p. 187)." In such circumstances, the appeals of the cult and of the drug are not easily distinguished But a similar and more specific drug finding is reported by Horn (1967) with regard to cigarette smoking. Those tobacco smokers who report several positive satisfactions from smoking find it harder to give up than those with only one. We (Blum and Associates, 1964 ) have found a like pattern in our studies of users of LSD-25; those who experimented and stopped reported fewer different satisfactions from the drug than those who continued. Whether continuing private or social use of drugs is inter-preted-as involvement, learning, multiple gratification, or multiple ra-tionalization, the observer needs to consider the import of multiple motivations as a critical feature for such use. If this be so, the historian will wish to ask how much opportunity a given culture provides for variety in individual drug use. The more restraint and the greater the sanctions limiting time and place and behavior, the more likely that variety in gratification will be restricted, and neither widespread sec-ular use nor individual drug dependency and commitment will emerge. This expectation is not new. We (Blum and Associates) have seen the phenomenon in comparing institutional (externally controlled) use of LSD-25 with noninstitutional ( private, social use. The same phe-nomenon seems to be apparent when one compares medical controls on morphine and relative infrequence of emerging dependency with the uncontrolled use characteristic of informal slum initiation into tak-ing heroin. This argument, of course, is restricted, since individuals who engage in acceptable institutional practices are already likely to be "adjusted," and societies capable of massively ordering behavior in institutionalized ways are already nonsecular and presumably without serious problems of deviancy. Child, Bacon, and Barry (1965) have shown this fact nicely in their cross-cultural alcohol studies; where drinldng is customary or integrated—a matter of acceptable institu-tional use—there are no problems with drunkenness, no matter how much drinking or drunkenness occurs, for it is approved and part of that larger life pattern which is deemed acceptable.

In considering motives, we must keep two other things in mind, neither of them derived from historical studies. One is the probability of a kind of simplicity in fact, as proposed by Cofer and Appley (1964Y, in which the underlying psychophysiology is viewed as an anticipation-invigoration mechanism that not only becomes shaped or channeled by experiences but is accompanied by some selective sensi-tization (sensitization-arousal) which is discriminating of environmen-tal events. (See also Pribram's [1967] new neurology of emotion.Y Thus, a catalogue of motives is not necessary to account for behavior. Learning does occur, shifts and channeling do take place; as a result, that which was diffuse becomes specific, and intentions do play a part in enhancing, invigorating, or driving action once there are sensitivity and arousal. The other feature is that individual behavior in reference to drugs need not be consistent, especially in regard to the determinants operating at various stages in drug use or in what sociologists might call a "career." The presence of esteemed individuals offering a mari-juana cigarette may be sufficient, in deferential or subordinate persons, to trigger experimental use. But continual use may be derived from a chain of habit arising from that social group's repetitive behavior, and specific intentions come into play when the person learns what the drug does for him, such as relieving his tension. The same shift in de-terminants along the chain from the point of initiation to continued use and even, perhaps, to augmented use and dependency—or to use termination—is observed with many different drugs and persons.

This contemporary observation leads one in a historical inquiry to focus on the opportunities within a given society or era for persons to alter the circumstances of their drug taking and to change the amounts of dosage or kinds of drugs, as well as the means and frequency of ad-ministration. Rephrased, the question can be one of individual free-dom of access to drugs and differing social environments; in turn, these include the opportunities for social mobility, for travel, for exposure to knowledge about individuals with different backgrounds and outlooks, for escape from institutional restraints—including those inculcated as beliefs or knowledge—and, perhaps, for the expression of individuality as such.

As social complexity increases (whether defined in terms of sodal organization, stratification, and the diffusion of authority within a society or as a sense of awareness of differences and complexity that comes with cultural diffusion, travel, and knowledge per se), one ex-pects variation will increase in individual behavior—even if within sanctioned roles. One also expects on intellectual as well as techno-logical grounds that more products will become available—induding drugs. Consequently, one expects the record of events to show that kinds of drug use within a society or era vary with that society's com-plodty. As a corollary, the more complex the society, the more one anticipates internal variety in drug use and in views about drug use. It is at this stage, when heterogeneity is introduced, that ideological as well as political and social conflict is expected; if so, such conflict might include conflicting evaluations of drug behavior. When social hetero-geneity is accompanied by increasing individuality as well—that is, by variability in conduct not prescribed by traditional institutional roles—one would anticipate not only disputes about what is desirable but also increas,ing disagreement about who is desirable. Perhaps, under these circumstances, the notion of drug abuse in its pejorative sense will be found—that is, bad people doing bad things. On the other hand, the concern with abuse simply as an observation of specific ill effects of pharmaceuticals—pain, mental disturbance, lethargy, and death—does not imply any conflict in values about conduct but only a concern with the health and welfare of individuals as such. Presumably, this concern is as old as man's nature as a social animal; however, its docu-mented expression might require that concern on the part of families or tribes be elevated to the status of an acknowledged value, as was indeed the case in ancient Greece, where preoccupation with health as a virtue as well as an immediate satisfaction was evident. These become questions for the epidemiologist-historian.

We shall see that awareness as to individually painful or disastrous outcomes from drug employment is not sufficient to arouse either social concern or a conclusion as to abuse; we shall also see that social concerns and the label of "abuse," or its equivalent, do not re-quire that any ill effects from drugs be demonstrated. For example, in the Moslem Eastern Mediterranean region, seventeenth-century rules strictly forbade the drinking of coffee. The death penalty was provided for owning or even visiting a coffee house. Behind this severity lay a threat unconnected with an evaluation of caffeine, for the coffee house had become a meeting place for leisured political malcontents who were thought to be secretly hatching plots against established po-litical and religious authority (El Mahi, 1962a).

Reactions against tobacco were just as severe and these oc-curred before any evidence related heart disease and lung cancer to smoking. In Germany, Persia, Russia, and Turkey, it was at one time death for the smoker—but by hangman rather than from carcinoma or infarction (Kolb, 1962). King James of England, in 1604, raged in righteous indignation over "the filthy, stinking weede, tobacco." His reaction, however, seemed a matter of national pride, for Englishmen, he thought, ought not to emulate the savages—that is, the American Indians who introduced the habit (Corti, 1932; Laufer, 1924a). Nev-ertheless, by 1614, over 300,000 pounds sterling "had gone up in smoke in one single year." Then, as now, economic considerations played no small part in public policy regarding drugs. The first Chi-nese imperial edicts banning opium were issued in 1729 and frequently thereafter. Initially, they appear to have been protests against a dis-astrous drain of silver from the empire. An element of chauvinism_was present, too, since the Chinese at that time were forbidden contact with "barbarians"—that is, with Europeans and their products, since most opium was being brought in by English, Dutch, and Portuguese merchants.

On the other hand, we know from early Egyptian manuscripts and later from classical Greek and Roman texts that there were gov-ernmental reactions to the specific disabling effects of drugs; in each of these lands—in particular places and at particular points in time—various efforts toward control were made. These aimed to reduce drunkenness, crimes committed on drunken persons, or the public lia-bilities to which drunkenness led, as in a drunken army's losing a battle. Ill effects from opium were also acknowledged early. Dioscori-des provides us with the earliest report but, later, Turks and Persians (Sonnedecker, 1958) were alert to opiate disabilities. Reports of dire effects from cannabis first came from Crusaders, whereas problems arising from other hallucinogens--for example, fly agaric—were not reported until recent centuries. What is striking is the inconsistency about judgments of ill effects from various mind-altering drugs over time and from place to place. If the range of specific drug effects is presumably constant—even though particular kinds of outcomes be-come more probable under various settings and with particular popu-lations and styles of use—at least part of the explanation for differing social evaluations of drug behavior must be found in the times them-selves and not in the pharmacological action.

PREHISTORY: ARCHAEOLOGICAL FINDINGS

For mankind before writing existed, archaeological findings are our only source for data on drugs. As an alternative or supplement, we may also examine contemporary nonliterate societies, assuming that their hunting and gathering, pastoral, or simple farming econom-ics are fair parallels to our preurbanized ancestors. Even now, many societies remain prehistoric in the sense of not being literate. The fact that their neighbors do know how to write has not meant that life in these societies lias been adequately described—a point strongly made in our chapter on cross-cultural drug use. In other words, at any par-ticular time, up to and including today, there is much left unsaid about how human beings use drugs. Indeed, no society exists, however mod-ern, for which an adequate social and epidemiological assessment of drug use is available. One would have expected differently, that so interesting a matter as what kind of pharmacology men practice on their minds would be widely inquired after, but it has not been so.

On the basis of archaeological data, there is one psychoactive substance, in several forms, which can be identified as having been used in prehistory. The date of discovery is unknown. The substance is alcohol. Tentative evidence from Catal Hiiyiik (Mellaart, 19677 in Anatolia of liackleberry wine and of beer dates from about 6400 B.c.

Predynastic Egyptain farmers, in about 4500 B.c., had learned to maximize fermentation and alcoholic content by malting their grain, or sprouting it before grinding (Linton, 19557, and all South-western Asian cultures had beer as a liquid staple. Hammurabi's laws, again a written document but nevertheless an archaeological one, set forth how much and what kind of beer workmen on different jobs were to receive. That beer, yeasty and full of proteins and vitamins, was an important food. (Certain Soutli American Indian cultures also used beer as food, and when missionaries inhibited Indian consump-tion, dietary deficiency and illness increased [Linton, 19551.7 Confirma-tory evidence of ritual beer drinking, the subject of stylized art themes, came from Egypt and Babylon between 2400 s.c. and 2800 B.c. (Childe, n.d.)- and from Sumer circa 3500 B.C. (Hoffman, 1956Y. A pitcher suitable for straining thick residue in early beer and termed a "beer jug” by its excavators has been found in Asia Minor; its date is circa 3000 B.C. (Schmidt, 1931).. Other Anatolian finds include pithoi with sieves dated circa 3500 B.c. (Mellaart, 1963), Anatolian sieve-spouted jars from 3000-2000 B.c. (Ozguc, 1963), and wine decanters circa 900 B.c. from Urartu (Burney, 1966). These dates are no longer prehistory. During this same Old Kingdom period, Egypt was engaged in a considerable commerce in which wine as well as beer was extensively traded in the Eastern Mediterranean region and possibly deeper into Asia a,s well. Evidence for this comes from written material —including the Old Testament—as well as amphorae (Wilson, 1951 In the Old Kingdom, beer was widely used but wine seems to have been limited to the upper class, whose tastes were already sophisticated, for wines were marked by grade of excellence (Encyclopaedia Britan-nica, 1965).. An early date for wine must be presumed since its com-merce implies considerable human experience in production and -Ship-ment, as well as a widespread and established consumer market. The Egyptian evidence of wine enjoyment as limited to the upper class may be interpreted—in the light of findings on other drugs which we shall discuss later—as very tentative evidence of a more recent intro-ductory date, since the general pattern, as we judge it, seems to be that both ritual use (religious, medical, festivaq and high-status secular use occur in earlier phases of a society's adoption of a drug. Beer in Egypt was used both ritually and secularly and by all classes; wine was restricted. In Europe, archaeological evidence for wine (Helbaek, 1961)- is available for Alpine peoples of what is now Northern Italy; themselves without writing, they had discovered wine making from grapes, blackberries, raspberries, elderberries, bittersweet nightshade, and the Cornelian cherry. The Beaker Folk of Europe, an early mer-chant people identified by their characteristic tumbler-like beakers, are thought to have traded heavily in beer—the beakers representing the vehicle of their stock in trade circa 2000 B.C. (Bibby, 1956; Childe, 1956; Linton, 1955; Piggott, 1965Y. Their distribution over Europe was rapid and their culture was present in the British Isles about 1800 B.C. A little later, beginning in 1300 B.C., another group of arti-facts was focused on drinking; Central European beaten-bronze vessels identified with the Urnfield cultures were found by archaeologists from the Caspian to Denmark (Piggott). These vessels in-clude a handled cup, a bucket, and a cup-shaped strainer, since wine was mixed with other materials even as it is now in Greece mixed with resin. Such vessels are presumed to have been filled with wine pro-duced in the Mediterranean, perhaps Southern Europe. In Central Europe, wine drinking was also a class phenomenon, since importation was expensive and, thus, in all likelihood the expensive bronze vessels were also an upper-class drinking utensil. (Piggott compares them with the tea sets imported to England from China along with the first tea imports.) Archaeological finds in Central Europe continued to show the importance of wine; for example, in France and Germany of the Hallstatt period, circa 750 B.c., imported Greek gold, bronze, and pottery amphorae were found. Later, the development of Celtic art in the fifth century B.C. was also linked to the wine trade, for non-representational Greek designs were transformed into Celtic forms and became adornments for that warrior aristocracy which Piggott so well describes. The archaeological data remain consistent, showing con-tinued trading in wine and its implements from south to north along the great rivers and passes. By the third century B.c., Italy began to produce wine and, within a few hundred years, production in Italy was 660 million gallons annually, according to Piggott's estimate. The amphorae of the first century were found from Marseilles to England; Belgic tombs revealed that the buried lord was allowed three amphorae for his afterdeath feast, each one holding about 5 gallons. Written materials cited by Piggott (Ammaianus, Pliny, Tacitus, Posidonius, Diodorus, and Pytheas) indicate that the Celts were considered in-temperate, for they were the first to be noticed to use wine not mixed with water. The Roman historian Ammaianus Marcellinus described them as "a race greedy for wine, devising numerous drinks similar to wine and among them some people of the baser sort, with wits dulled by continual drunkenness . . . rush about in aimless revels." They also used mead and beer made from barley or wheat.

With regard to psychoactive drugs other than alcohol, we shall see in our discussions of opium that archaeological evidence from Cyprus, Crete, and Greece shows that opium was known and prob-ably used ritually about 2000 B.c. (Kritikos and Papadaki, 1963; Merrillees, 1962, 1963). Writing was known at this time in nearby cultures (disregarding untranslated Cretan linear A) and disputed suggestions indicate that earlier than 1500 B.c. (see Sonnedecker, 1958) Egyptians were using opium medically; later texts, Assyrian seventh-century ones, describe its cultivation.

We have come across suggestions pertaining to archaeological fmds of cannabis in early Central European cultures, but although we pursued these through correspondence with paleoethnobotanists (Helbaek, 1965), we have been unable to verify them. The earliest acceptable archaeological evidence appears to be from the Pazarik excavations of the Altai Scythian group dated circa 430 B.c. (Ru-denko, 1953; see discussion by Rice, 1957). The burial objects in-cluded the tent, cauldron, stones, and hemp seed.s exactly as described by Herodotus in the Histories prior to 450 B.C. As for other psycho-active substances, some scholars (Wasson and Wasson, 1957; Wasson, 1963, 1967) have claimed widespread early use for the mushroom Amanita muscaria primarily on the basis of philological-ethnographic evidence. Gordon Wasson (1963) suggests that "the adoration of the fly agaric was at a high level of sophistication 3500 years ago among the Indo-Europeans (p. 413)." Another claim for very early drug use is advanced by Willey (1966) and cited by Wass& (1967), who pro-poses that chewing lime or ashes with a narcotic—such as bétel nut and coca leaf and perhaps even the premastication per se of kava or grains to produce fermented drinks—in being both an Old World and New World practice is a Paleolithic survival. This is, of course, only speculation. Archaeological evidence of tobacco smoking among South-western American Indians yields dates of 200 A.D. and for Eastern Coastal Indians about 800 A.D. We have been unable to uncover sound archaeological evidence for other psychoactive substances in our own prehistory—that is, before 4000 B.C.

Another approach to prehistory is to assume that contemporary nonliterate societies represent styles of life extant before any society be-came literate. Specifically, the assumption is that generalizations can be made from the isolated hunting and gathering societies which ap-ply to our ancestral groups prior to their agricultural settlement and later urbanization. What is stated is essentially a theory of cultural evolution, diffusion, and implied limited diversity. Thus, it is argued that isolated hunting, fishing, fowling, and gathering folk of today, as well as some pastoral herders, have characteristics that are much like those of prehistoric—and specifically preagricultural—peoples. Clark (in Kroeber, 1953a) has discussed the problems and merits in such an assumption; Steward's commentary (in Kroeber, 1953a) is also rele-vant. As long as one is cautious, and recognizes the need to match ecology as well as life style as closely as possible, the comparative method based on that assumption is useful. Clark cites in particular the value of contemporary folk usage in interpreting archaeological data. We (Blum and Blum, 1968) would add, on the basis of our work, that such survivals are also invaluable in interpreting early his-tory. In either case, the comparative method based on study of sur-vivals offers optimism—but not proof—for a comparative method based on parallels and general evolutionary assumptions.

Since in all likelihood there has always been a multiplicity of hu-man societies (Coon, 1962; Linton, 1955; Steward, 1953), it would be most unwise to assume that any particular technique or usage, at least with regard to drugs, was common to them all. Today, given tremendous opportunities for cultural diffusion over thousands of years, the pattern is still one of diversity of drug use among nonliterate and literate societies (Schultes, 1967a) ; among today's disappearing hunt-ers and gatherers, diversity is also the rule. Nor can any statements be made which assume a fixed and inevitable course of cultural evo-lution, although regularities are again observed (Adams, 1966; Linton, 1955). Adams, for example, concludes that when cultural evolution occurs there is

A common core of regularly occurring features . . . that social behavior conforms not merely to laws but to a limited number of laws, which perhaps has always been taken for granted in the case of cultural systems . . . and among "primitives" (p. 175).

Simply knowing what drug-use patterns exist at a given level of social development does not allow one to anticipate exactly what forms of use will follow, but there should be similarities in invention as well as in practice—for example, the development of beer drinking after grain production has begun, the invention of distilling after fermentation is discovered, the increase in complexity of drinking equipment (beakers, strainers, and so on) as commerce and technology expand, the pro-duction of manufactured pharmaceuticals after technical chemistry is introduced, the spread of application of a manner of drug preparation or administration from one drug to another after the method has been introduced, and the increasing diversity of drug uses and effects as societies grow secular, larger, and more heterogeneous. What cannot be assumed is that a given society, especially an isolated hunting and gath-ering one, will inevitably proceed to a more complicated development or that use of a drug once inaugurated will be maintained.' Which will occur, for example, upon exposure to a more complex colonizing power, resistance to or adoption of its drugs? If the latter, will there be ac-commodation with social control or will there be, as has been so often the case, the development of individual and community-wide alcohol problems? For example, Child et al. (1965) found that problem drink-ing most often occurs in those societies where new drinking patterns have been introduced after contact with a more modern society.

In Chapter Eight we report on our cross-cultural study of drug use. Within the dubious limits of accuracy of these primarily contem-porary observations on nonliterate societies, our conclusion is that alcohol is the most commonly used substance and that widespread use of alcohol is consistent with the relative ease of discovering fermenta-tion in the normal course of storing foods—a practice of hunting and gathering peoples as well as agricultural folk. Hunting and gathering societies are capable, as Helbaek's Alpine evidence shows, of such pro-duction although it is impossible to know whether the Alpine tribes in question discovered it, since they could have developed berry wine after the diffusion of knowledge of fruit or grape wines from elsetvhere. Loeb (1943 ) cites Beals and Cooper to the effect that modern use of intoxicating beverages is generally limited to agriculturists, such folk as the Australian, Tierra del Fuegian, or California Indian hunters. Loeb argues that the discovery of fermentation and the development of drinking practices were likely to have occurred in many places at any time after the development of agricultural practices. (These in-clude harvesting wild cereals as well as cultivation per se. ) His argu-ments as to the context in which drinking then occurred are based on ethnographic descriptions. We shall return to these, but we shall first point to a limitation of inference from ethnographic accounts and then to a summary of cross-cultural data on drug use by hunting and gath-ering peoples, whose known acceptance of drugs from other societies —including Western colonizers—was minimal.

In our cross-cultural study we found that tobacco ranked sec-ond among the psychoactive substances used. Among nonagricultural peoples it is commonly found. Reasoning backward, one would assume that by Neolithic times some Old World peoples at least would have smoked it. This would be in error, for all species of the plant, with an Australian exception, are native to the Americas. Tobacco use through-out Asia and Africa followed the introduction of American Indians' smoking techniques into Europe in the late 1500's. In a later chapter we present the history of tobacco's diffusion. We have the warning: what appears to be an indigenous practice may well have been borrowed.

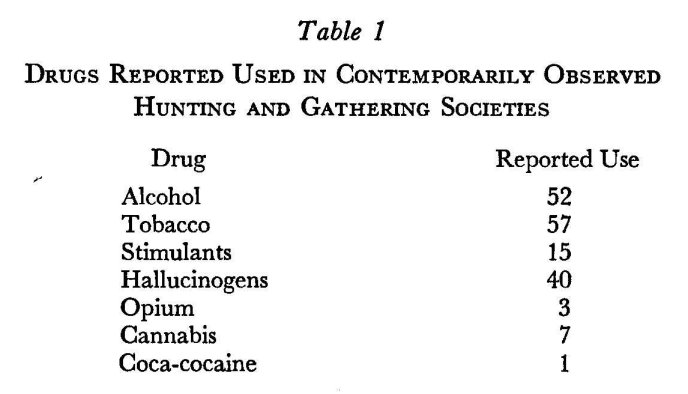

Looking at hunting and gathering societies about which we have data, ninety-two in number, we find the distribution in Table 1 of reported (and by no means do we assume this is actual drug use.

We might reasonably expect that at least some of these societies discovered their own drugs rather than having been introduced to them, however indirectly, from more sophisticated sources, such as pastoral, agricultural, or urban people. After all, Western societies learned tobacco use from American Indians, are now learning about exotic hallucinogens from isolated South American groups (for exam-ple, Wassén, 1967; Wass& and Holmstedt, 1963; Schultes, 1967b)', learned about coca-cocaine from the highland Indians of the Andes, discovered mushroom eaters after anthropological observations in Si-beria or Mexico (Wasson, 1958; Wasson and Wasson, 1957), heard about peyote from North American Indians, and so on. Consequently, it is possible that some of these discoveries were early enough to qualify as prehistoric when the history under discussion is that of Western civilization—that is, before 4000 B.C. (excluding alcohol, which we assume may have been fermented by the time of early agricultural settlements. The possibility exists, then, that those hunting and gathering tribes in Paleolithic, Mesolithic, and Neolithic times did use mind-altering drugs. However, we know of no proof on either side of the question.

If they used drugs, how did they do so? Again, our estimates must be based on the inferences from archaeology as to life styles and on contemporary observations of groups similar to some Stone Age man. Early man lived in small groups, the size of which was controlled by food supply and other variables such as disease and predators. His religion and ritual developed early, probably, as James (1957Y con-tends, 100,000 years ago '(and perhaps 500,000 years ago if Peking man was the death-feasting cannibal James proposesT. Whether or not the earlier dates are accepted, the archaeological evidence from paint-ings, burials, and steles .(see Anati, 1964, for an example of interpretive method Y certainly for the upper Paleolithic (40,000-8500 B.C. follow-ing Piggott's dating rather than Zeuner'sj is very strong indeed for a system of beliefs that imply attempts to control nature through ritual and magical means as well as by simply physical means. It is very likely that medicaments were also developed early. Food gatherers must have engaged in pliarmacognosy to learn to identify safe and edible plants. During these sometimes perilous trials, they discovered plants with other qualities, including those leading to changes in phys-ical function or in feeling. Flannery 0965Y, in discussing preagri-cultural subsistence in the Near East, emphasizes the intensive col-lection of plants, based on paleobotanical evidence, and cites data indicating that such collection precedes agriculture for a long period. He notes that an immense variety of plants were available and sug-gests that from 40,000 to 10,000 B.c. man developed the exploitation of plant resources.2

Both religious and medical practices are limited to particular settings, are usually supervised by some type of authority, and, when magically elaborated, include rituals which are, if current practice is any guide, compu/sive or not allowing of variation. Given the early documented use of mind-altering drugs in medicine and religion—certainly by 2000 B.C. in the Eastern Mediterranean and Western Asia —it is likely that earlier undocumented use was along the same lines.3

In addition to specific ritual and the necessarily controlled use of psychoactive drugs in religion and healing, there is early evidence for using at least alcohol as food. In later periods (see McKinlay, 1949; Piggott, 1965), drugs were also used for social purposes such as ceremonial occasions or for informal, spontaneous, and noninstitution-alized gatherings like parties. Long before the time of Christ, descrip-tions were written of private or individual-centered drug use, as, for example, in drinking without regard for social circumstances that re-sulted in stupor, euphoria, and other comparable states. Opium and perhaps cannabis are also implicated by that date. Drug use that is without ritual or ceremonial significance we term as "secular." This approximates culturally the unintegrated drug use referred to by Child et al. (1965)%

On the basis of observations in contemporary nonliterate so-cieties, where most behavior is self- and other-controlled and is there-fore carefully role-prescribed, we assume that drug use in prehistory was likewise integrated and, even though social and individual com-ponents in setting and intent were likely to have been present, was not secular. Ford's (1967 ) description of kava drinking in Fiji is a good example of how a variety of behaviors can be connected with drug use without its ever becoming private, individualistic, or escapist. Indeed, the very notion of "individual" or "private" is inconsistent with life in little communities (Redfield, 1960) for it implies an autonomy and self-centering not known until the end of the Middle Ages (Ullmann, 1966). This, of course, does not rule out the function of drugs to grease the skids of social interaction or to enhance shared euphoria.

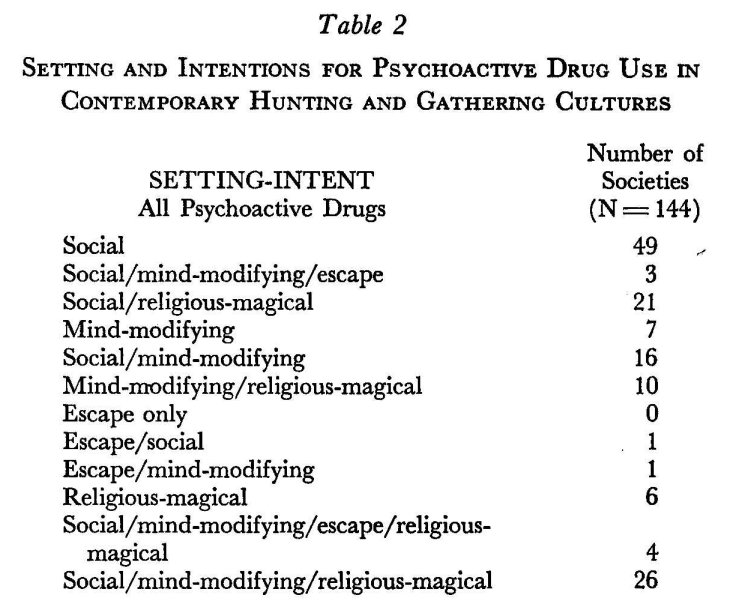

In Table 2 we present observations from contemporary hunting and gathering societies made prior to culture change under Western impact and showing the settings and intentions for psychoactive drug use as reported by observers.

As expected, individualistic drug use for escape is least frequent, although its presence at all is inconsistent with a theoretical picture of the group-centered little community. Similarly, mind modification outside of religious-magical settings is also individualistic but present in hunting-gathering societies. Social settings-intentions do not imply a secular pattern, but they are a step removed from the religious and healing ceremonial uses implied by Loeb and others as primary to psychoactive substances. Table 2, then, suggests the conclusion that—at least among the hunting-gathering societies which constitute our limited sample—religious-magical functions for drugs are less common than social uses and no more common than individualistic functions. We further conclude that expectations of more frequent and more elaborate religious-magical drug functions represent observer romanti-cism and that if prehistoric societies did use psychoactive drugs as hunting-gathering societies use them now, they used them primarily for simple social facilitation and shared personal pleasures. Magical superstructures supported or elaborated by drugs would have been less common, if our backwards-in-time extrapolation holds, and no more common than individualistic and indeed private (although rarely es-capist) functions for drugs. Such a conclusion implies that primitive man re,sembled modern man in the uses to which he put psychoactive substances and that there will be little justification for those generalized romantic abstractions that moderns build to house their images of strange and far-away peoples.

1 For example, Wassén (1967) describes how varied forms of snuff use have been lost to South and Central American Indians.

2 The written record of prescriptions is almost as early as writing it-self. LaWall (1927) dates the original of a later transcribed Egyptian papyrus containing a prescription at 3700 B.c. The Ebers Papyrus, circa 1550 B.c., con-tained remedies listing wine, beer, oil, onion, vinegar, yeast, turpentine, castor oil, myrrh, wormwood, cumin, fennel, juniper berries, henbane, gentian, man-dragor, and others. There are also early Biblical and Babylonian apothecary's guides. In Indian medicine, Rig-Veda medicinal uses of plants are claimed (Chopra cited in Krieg, 1964) before 1600 B.c. and drug therapies described about 1000 B.C. in the Sushruta Samhita.

3 Loeb (1943) has proposed that in the case of alcohol the initial focus was always religious and that drunkenness at sacred feasting thus became an obligatory communion. The Catholic use of wine in communion would then be interpreted as a vestigial practice; the drunkenness of the Guatemalan Indian in order to communicate with ancestral spirits (Blum and Blum, 1965; Bunzel, 1940) would be a contemporary demonstration. Outside of the sacrament, "de-viant" drinking would not be allowed. Indeed, Bunzel notes that under the Aztec law nonworshipful drinking was punishable by death, except for persons over seventy. Loeb notes that the Moi of Indo-China put to death any who failed to get drunk at religious ceremonials. According to Loeb, only with in-creased production and storage facilities does secular drinking become possible, at which time extreme sanctions are no longer appropriate. He does not account for anthropological evidence showing secular drinking among societies with lim-ited facilities for alcohol production and storage.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|