Controlling Psychoactive Substances: The Current System and Alternative Models

| Reports - Report of the King County Bar Association |

Drug Abuse

Report of the Legal Frameworks Group to the King County Bar Association Board of Trustees:

Controlling Psychoactive Substances: The Current System and Alternative Models

King County Bar Association Drug Policy Project

1200 Fifth Avenue, Suite 600 Seattle, Washington 98101 206/267-7001 www.kcba.org

Introduction

This report is the product the Legal Frameworks Group of the King County Bar Association Drug Policy Project, which included the participation of more than two dozen attorneys and other professionals, as well as scholars, public health experts, state and local legislative staff, current and former law enforcement representatives and current and former elected officials. The Legal Frameworks Group was established as an outgrowth of the work of the Task Force on the Use of Criminal Sanctions, which published its own report in 2001 examining the effectiveness and appropriateness of the use of criminal sanctions related to psychoactive drug use.

The Criminal Sanctions Task Force report found that the continued arrest, prosecution and incarceration of persons violating the drug laws has failed to reduce the chronic societal problem of drug abuse and its attendant public and economic costs. Further, the Task Force found that toughening drug-related penalties has not resulted in enhanced public safety nor has it deterred drug-related crime nor reduced recidivism by removing drug offenders from the community. The Task Force also chronicled the numerous “collateral” effects of current drug policy, including the erosion of public health, compromises in civil rights, clogging of the courts, disproportionately adverse effects of drug law enforcement on poor and minority communities, corruption of public officials and loss of respect for the law. Based on those findings, the Task Force concluded that the use of criminal sanctions is an ineffective means to discourage drug use or to address the problems arising from drug abuse, and it is extremely costly in both financial and human terms, unduly burdening the taxpayer and causing more harm to people than the use of drugs themselves.

The Legal Frameworks Group, building on the work of the Criminal Sanctions Task Force, moved beyond the mere criticism of the current drug control regime and set out to lay the foundation for the development of a new, state-level regulatory system to control psychoactive substances that are currently produced and distributed exclusively in illegal markets. The purposes of such a system would be to render the illegal markets in psychoactive substances unprofitable, to improve restricting access by young persons to psychoactive substances and to expand dramatically the opportunities for substance abuse treatment in the community. Those purposes conform to the primary objectives of drug policy reform identified by the King County Bar Association in 2001: to reduce crime and public disorder; to enhance public health; to protect children better; and to use scarce public resources more wisely.

This report is the third of five major research initiatives supporting a resolution by the King County Bar Association seeking legislative authorization for a state-sponsored study of the feasibility of establishing a regulatory system for psychoactive substances. This report describes the current system for controlling psychoactive substances at the federal and state levels and identifies specific proposals for fundamental drug law reform that have been put forward over the years, including scholarly papers and other state-level legislative proposals.

THE CURRENT SYSTEM OF DRUG CONTROL

The current legal framework for drug control is composed of three legal tiers: international treaties; federal statutes and regulations; and state statutes and regulations. The laws at each level function as an interlocking system intended to limit certain medical uses of drugs, to prevent the diversion of certain drugs for “non-medical” uses and to enforce the absolute prohibition of the use and sale of certain other drugs.

International Treaties

The United States is a party to three international treaties that provide the basic legal framework for a worldwide system to control drugs that have been determined to have a high potential for abuse.1 The purpose of the treaties is to limit the use of drugs to medical and scientific purposes only.2

Most nations are signatories to the U.N. Conventions, which prohibit the use and sale of the same drugs that are prohibited in the United States.3 The U.N. conventions are part of the large body of international law that is not “enforceable” in the traditional sense, but signatories to the drug control treaties are subject to enormous diplomatic pressure, particularly from the United States, not to enact national laws that depart from the prohibition framework. The International Narcotics Control Board (INCB), an independent body within the United Nations, serves more as a panel to monitor adherence to the U.N. conventions rather than as an enforcement agency, but it often voices support for or objection to drug policy developments around the world, consistent with prevailing

U.S. domestic and foreign drug policy interests.4

U.S. Drug Control – Federal Preemption

The federal government regulates psychoactive substances under a series of statutory schemes, mainly under Title 21 of the United States Code. These include the Controlled Substances Act, the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act and the enabling acts authorizing the Office of National Drug Control Policy and the Drug Enforcement Administration. Other miscellaneous federal initiatives found throughout the U.S. Code address drug use as it relates to other areas of law regulated by the federal government, including enhanced penalties for use of prohibited drugs in federal prison5 and federal aid for state drug courts.

Controlled Substances Act

The Controlled Substances Act (CSA)6 begins with congressional findings that many drugs being controlled have a legitimate medical purpose, but that the illegal importation, manufacture, distribution and possession and improper use have “a substantial and detrimental effect on the health and general welfare of the American people.”7 The CSA authorizes the Attorney General to place controlled substances on a rank of schedules8 and sets forth standards to guide the scheduling of substances, such as potential for abuse, pharmacological effect, degree of addictiveness and whether the U.S. is treaty-bound to control a drug. 9 The CSA prescribes five schedules and assigns certain substances to each of the schedules.10 All substances listed under Schedule I are stated to have “a high potential for abuse, … no currently accepted medical use in treatment in the United States, and … a lack of accepted safety for use of the drug or other substance under medical supervision” and are strictly prohibited for any sale or use.11 Some common examples of the hundreds of controlled substances under the various schedules include:

Schedule I – Heroin, marihuana, LSD, other prohibited substances

Schedule II – Morphine, Oxycodone (Percodan, Percocet, OxyContin), codeine, cocaine, meperidine (Demerol), Ritalin, amphetamines, secobarbital, pentobarbital

Schedule III – Codeine combinations (Tylenol with codeine), hydrocodone combinations (Vicodin, Lortabs), Marinol Schedule IV – Phenobarbital, benzodiazepines (Librium, Valium), Propoxyphene (Darvon), Talwin Schedule V – Codeine cough syrups, antidiarrheals

The CSA includes registration requirements for persons who manufacture or dilute a controlled substance,12 as well as labeling and packaging requirements as required by regulation of the Attorney General,13 and authorizes the Attorney General to set production quotas.14 The Act requires every registrant to keep records of inventory, deliveries, etc.,15 and requires order forms to be used, copies of which go to various authorities,16 including prescriptions.17

The CSA makes it a crime to manufacture, distribute or possess a controlled substance with such intent unless authorized by the Act18 or to conspire to do the same.19 There are specific sentencing guidelines depending on the substances and quantities involved,20 as well as to fail to register or operate beyond the scope of such registration, 21 as outside one’s quota,22 or to simply possess a controlled substance unless pursuant to a prescription, 23 which subjects someone to one year in prison and a “minimum” fine of $1000 for a first offense, except for cocaine base which has a sentence of five to 20 years, regardless of amount, with a five-year mandatory minimum sentence. The Act also authorizes civil penalties for “small amounts” of certain controlled substances with fines up to $10,000 to be assessed by the Attorney General, with a right to a trial de novo.24

Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act

The Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act25 defines the term “drug” in part as:

(A) articles recognized in the official United States Pharmacopoeia, official Homoeopathic Pharmacopoeia of the United States, or official National Formulary, or any supplement to any of them; and (B) articles intended for use in the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease in man or other animals; and (C) articles (other than food) intended to affect the structure or any function of the body of man or other animals; and (D) articles intended for use as a component of any article specified in clause (A), (B), or (C).26

The Act authorizes the Secretary of Health and Human Services to promulgate regulations 27 and conduct examinations and investigations,28 and establishes the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) within the Department of Health and Human Services.29 The Secretary is authorized to cooperate with “associations and scientific societies” in the revision of the U.S. Pharmacopoeia necessary to carry out the work of the Food and Drug Administration. 30

Federal Agencies

The Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP)31 and the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA)32 are both authorized under Title 21 of the U.S. Code. The ONDCP, part of the Executive Office of the President, was established by the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988. The purpose of the agency is to establish policies, priorities and objectives for drug control in the nation. Its stated goals are “to reduce illicit drug use, manufacturing, and trafficking, drug-related crime and violence, and drug-related health consequences.” The agency releases an annual National Drug Control Strategy that establishes a program, budget and guidelines for anti-drug efforts at the national, state and local levels.33

The DEA is an arm of the U.S. Department of Justice. Its mission is:

to enforce the controlled substances laws and regulations of the United States and bring to the criminal and civil justice system of the United States, or any other competent jurisdiction, those organizations and principal members of organizations, involved in the growing, manufacture, or distribution of controlled substances appearing in or destined for illicit traffic in the United States; and to recommend and support non-enforcement programs aimed at reducing the availability of illicit controlled substances on the domestic and international markets.34

Alcohol Exemption under the 21st Amendment

The 21st Amendment to the U.S. Constitution repealed the 18th Amendment, a national prohibition on the sale of alcohol. Section 2 of the 21st Amendment has been interpreted to give the individual states the right to make their own laws governing the manufacture, distribution and sale of alcohol within their borders.35 The federal government does regulate the importation and interstate transportation of intoxicating liquors under the Federal Alcohol Administration Act of 1935, and it has the sole power to regulate liquor sales in the District of Columbia, on government owned military reservations and on tribal reservations.36

A pending decision from the U.S. Supreme Court in 2005 could redefine the reach of federal commerce power against the 21st Amendment, with internet-based winemakers seeking direct shipments nationwide arguing that the states’ regulation of alcohol is an impediment to interstate commerce.37

What the Current System Allows

The drug control system under the federal Controlled Substances Act can be said to operate fairly effectively with regard to substances whose manufacture and distribution are closely regulated, although there have been some persistent problems of diversion of certain regulated substances to street markets, such as Oxycontin. In general, however, the regulation of the scheduled drugs abides by the principle of controlling substances to a degree that is commensurate with their known propensity for harm and problematic use. There is one critical and enormous exception to this principle – the absolute prohibition of substances in Schedule I, which has ironically resulted in the ceding of control of those so-called “controlled substances” to the black market, effectively leaving their production and distribution exclusively in the hands of criminal enterprises.

On a global scale the regime of drug prohibition has wrought devastating consequences, as powerful gangs threaten stability and corrupt governments in the poorer “source” countries, people and the land are poisoned by drug eradication efforts and terrorist networks tap into the big business of prohibited drugs to fund their operations. In the United States and Europe the poor are also drawn to the fleeting profits of the drug trade and end up in jails and prisons in grossly disproportionate numbers.38

U.S. efforts to suppress drug production from “source” countries have repeatedly resulted in more efficient production within those countries and in the displacement of production to other countries. Despite the destruction and seizure of hundreds of metric tons of prohibited drugs each year, the supply “keeps flowing in at prices that … are still low enough to retain a mass market… [and] making U.S. borders impermeable to heroin and cocaine has proven impossible.”39 Data from the White House drug office itself show that the U.S. drug interdiction strategy has been an abysmal failure, as prices for cocaine and heroin remain at or near their all-time lows, while the purity levels are at their all-time highs.40

The prohibition of alcohol in the early 20th century in the United States was a failed experiment that revealed how such “a ban could distort or corrupt law enforcement, encourage the emergence of gangs and the spread of crime, erode civil liberties, and endanger public health by making it impossible to regulate the quality of a widely consumed product.”41 Drug prohibition has given rise to the same effects and is now prosecuted on an international scale.

The Business of Dealing Drugs

History has shown that high profits are assured to those who provide through the “black market” a prohibited product for which there is an unrelenting demand. Without any regulation, this black market regulates itself through such illegal means as violence and money laundering. The so-called “profit paradox” has been highlighted as one of the fundamental flaws in the prohibitionist drug control strategy, whereby the high street-level cost of prohibited drugs leads to higher profits, which, in turn, create stronger incentives for criminal enterprises to continue doing business in prohibited drugs.42

The black market in psychoactive substances runs rampant in urban, suburban and rural areas alike throughout the United States, and on a global scale the trade in prohibited drugs generates over $400 billion a year,43 with as much as $500 million laundered through the U.S. financial system each year.44 What are essentially small, illegal corporations are sprouting up in an increasingly sophisticated black market, with salaries, per diem and meal allowances, manufacturing setups and inventory. These clever operations go to great lengths to avoid detection. 45

The trade in marijuana, a substance known for its pacifying qualities, has grown more violent as highly organized, well-armed groups that once focused on cocaine and heroin are now dealing in marijuana, as well. The increase in price due to higher potency, varieties grown indoors domestically has made dealing in the drug more attractive to gangs who use violence to maintain control of their markets.46

Drug dealers are increasingly moving into rural areas, where crimes rates are rising in comparison with most cities. Rural areas with incomes below the poverty level and few job opportunities are ripe for the prohibited drug trade and limited law enforcement resources in poor counties allow drug dealers to maintain flourishing business. Junior high and high school students in rural areas are using more crack cocaine and even more methamphetamine, with heroin use rising to comparable levels among young people in metropolitan areas.47

Towns along the U.S. border with Mexico are being taken over by violence arising from the drug trade, as the powerful Mexican cartels ha ve “turned the streets into battlefields and plazas overtaken by gunmen firing grenades and assault weapons.”48 The murder of a journalist from Nuevo Laredo had a chilling effect on news organizations along the border, as the editor of one newspaper admitted, “We censor ourselves. The drug war is lost. We are alone. And I don’t want to put anyone else at risk for a reality that is never going to change.”49

Mexican drug dealers are taking advantage of the high rates of Mexican immigration to factory and farming towns in the United States, using those towns as distribution centers for methamphetamine, heroin, cocaine and other drugs. The dealers use the cover of working immigrants to blend into the community and recruit drug couriers from the immigrants who cannot find jobs or have lost theirs.50 Mexican cartels have largely taken over marijuana production in the U.S., concentrating their cultivation efforts in California rather than trying to smuggle it from Mexico. Mexican cartels are known to be growing marijuana on Forest Service lands throughout the West.51

With such high profit margins, corruption is rife among underpaid government officials and police. It is estimated that Mexican drug gangs make $3 billion to $30 billion annually by smuggling cocaine across the U.S. border. The gangs are believed to have police, politicians and judges on their payrolls. This was evident when the entire police force of the state of Morelos was suspended after the chief of detectives was arrested on federal drug trafficking charges.52 Drug gangs also put pressure on law enforcement either to accept kickbacks or risk retribution. 53

The black market in prohibited drugs has even caused a surge of violence in Britain, as London saw its murder rate double in 2003, fueled by an increase in the use of guns, primarily in the drug trade.54 The United Kingdom is also experiencing a dramatic influx of “drug mules” from Jamaica.55 Drug mules often carry 2 pounds of drugs in their bodies, in up to 25 drug-stuffed condoms or latex gloves.56 Considered expendable by the drug barons, drug mules risk arrest and even death if one of the pellets of drugs inside their bodies burst and they are often poor women willing to take the desperate measure of ingesting drugs in order to make some money. 57

The black market in prohibited drugs has become deeply entrenched in poor countries, where government officials find themselves unable to resist the immense profits. Since the late 1970s, for example, the North Korean government has reportedly been encouraging North Korean farmers to produce opium poppies and government-subsidized factories then process the poppies into heroin. It is suspected that methamphetamine found in Japan and China also comes from North Korea.58 The illegal opium trade is now seen as a bigger threat to democracy in Afghanistan than al Qaeda or the Taliban, as local government officials and those running for office are often involved in the drug trade.59

Financing Terrorism

Known terrorist organizations are tapping into the prohibited drug trade to finance their operations. As Antonio Maria Costa, the Executive Director of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, explained:

“It has become more and more difficult to distinguish clearly between terrorist groups and organized crime units, since their tactics increasingly overlap. The world is seeing the birth of a new hybrid of ‘organized crime – terrorist organizations’ and it is imperative to sever the connection between crime, drugs and terrorism now.”60

According to Mr. Costa, “Without a doubt, the greatest single threat today to global development, democracy and peace is transnational organized crime and the drug trafficking monopoly that keeps this sinister enterprise rolling.”61

The prohibited drug trade now actively funds the Taliban and al-Qaeda in Afghanistan. 62 Moroccan drug gangs trafficking in hashish have been linked to al-Qaeda sleeper cells in several countries in Europe, including the terrorists who attacked commuter trains in Spain. 63 The trade in prohibited drugs also provides fund ing for Hezbollah and Hamas, tied to a methamphetamine trafficking organization.64

Environmental Harms

In an attempt to fight prohibited drugs at the source, the U.S. is fumigating crops in Colombia with a strong herbicide. While the principal target is coca, the fumigation has had detrimental side effects, saturating the land and seeping into tributaries, affecting the health of Colombia n farmers and their children. The concentration of glyphosate, or Roundup®, in the herbicide being sprayed in Colombia is 26%, compared with the 1% the Environmental Protection Agency recommends for use in the U.S. Health officials have found widespread health problems in Colombia’s fumigated regions, including chronic headaches, fevers, skin ulcers, sores, flu, diarrhea and abdominal pain. 65

Despite human attempts to control the natural environment to combat drugs, the plant world has a way of adapting, as a new strain of coca plant has been identified in Colombia. First reports were that the powerful drug cartels had genetically modified coca plants to produce a strain that is resistant to glyphosate. However, testing of the plant revealed no evidence of genetic modification, leaving the explanation to selective breeding. Cuttings were made and distributed to dealers and farmers eager for a plant that could withstand the fumigation. Because all other vegetation competing for nutrients around these resistant coca plants has been killed off by the spraying, the coca plants have become more productive.

Unfortunately, in order to combat this new strain, the U.S. government is considering switching from Roundup to Fusarium oxysporum, a plant-killing fungus that is known to attack coca. Because it is a fungus, it can live on in the soil with the potential for mutating and attacking subsistence crops, such as corn and tomatoes. Florida’s Department of Environmental Protection rejected the use of the fungus after finding that it was “difficult, if not impossible, to control [Fusarium’s] spread.” Nevertheless, the

U.S. is still trying to convince the Colombian government to make the switch. 66

Harsh Punishment and Racial Disparities

In the United States the response to prohibited drug use calls for harsh criminal sanctions, distinguishing the U.S. with the highest incarceration rate in the world. In 2003, nearly 1.7 million people in the U.S. were arrested for a drug offense, more than for any other criminal offense.67 Eighty-one percent of those arrests were for possession of prohibited drugs.68 At least three-quarters of the roughly $40 billion the U.S. spends each year to control drug abuse is to apprehend and punish drug law violators rather than providing prevention and treatment services.69

Although whites use prohibited drugs at a rate roughly equal to that of African-Americans and Latinos,70 three-quarters of those incarcerated for drug law violations are non-white.71 African Americans make up about 13% of regular (monthly) drug users; 35% of those arrested for possessing drugs; 55% of those convicted; and 74% of those sentenced to prison. The re are now more young black men in jails and prisons than there are in colleges and universities.72 Full of rage from having learned a set of survival skills in prison, young black men may also have picked up a drug habit, including the injection of drugs with shared needles, putting them at risk for HIV and other blood-borne illnesses that they then take back to the community. These men also have a reduced chance of employment and of receiving benefits like food stamps, housing and student financial aid. Poor, minority communities are filled with young men whose futures are bleak, leading many to re-offend.73

Impaired Administration of Justice and Civil Rights

The effect of drug prohibition on crime has compromised the total administration of justice in American society, sapping resources from the civil and family courts in order to process the huge number of drug-related cases in the criminal courts. In addition, the large number of arrestees for drug law violations overloads the police, giving rise to irregular procedures to cope with the work pressures. The difficulties of enforcing laws against consensual activity such as the sale and use of prohibited drugs has led to extensive use of informants, wiretapping and “bugging” and often to entrapment, to arrests and searches prior to obtaining proper warrants and even to the offering of drugs to physiologically-dependent addicts in order to get information. 74

The clogging of the courts with petty drug cases has often led to hasty bargaining to clear the dockets, resulting in penalties that bear little consistent relationship to the actual conduct in question and that are more related “to the social status of the accused and his retention of an astute lawyer.”75 Largely due to the disproportionately adverse effect of drug law enforcement on racial minorities and the poor, many in those segments of the public have come to disrespect law enforcement and the courts and have further acquired attitudes conducive to the violation of laws and to non-cooperation with law enforcement.76

The “War on Drugs” has also had the effect of militarizing the police. Over 90% of cities with populations over 50,000, and 70% of smaller cities, have paramilitary units in their police departments, sometimes equipped with tanks, grenade launchers and helicopters.77

The federal Controlled Substances Act and most of the complementary state statutes, as well, have general forfeiture provisions with respect to any property used to violate the drug laws78 Seizure is authorized prior to conviction upon the issuance of a warrant.79 The police department may often keep the property seized, creating an ethical dilemma and a conflict of interest.

Curbs on Legitimate Medical Practice

Federal laws restricting the prescription of regulated pharmaceutical drugs have limited appropriate medical treatment, especially for patients with chronic and severe pain who rely on opioid analgesics. Patients suffering from severe pain caused by conditions such as cancer, degenerative arthritis and nerve damage have usually tried surgery and other medications like codeine before turning to stronger opiates such as hydrocodone (Vicodin), oxycodone (OxyContin), morphine or methadone.80 With the increased diversion of these drugs, federal and state local authorities have increased their scrutiny of doctors who prescribe pain medications. Twenty-one states have prescription drug monitoring programs.81 Unfortunately, the signs the authorities are looking for – prescribing high volumes of narcotic painkillers for extended periods, prescribing potentially lethal doses or prescribing several different drugs – could also be signs that a doctor is responsibly treating someone with intractable pain. A patient visiting several pharmacies, what could be considered “doctor shopping” by the authorities, may be an attempt to attain an adequate level of pain control. The pressure on the doctors have left many to stay away from the practice of pain management altogether, making it difficult for patients with severe pain to get the relief they need.

Doctors treating chronic pain are desperate for official guidance so that they may responsibly treat their patients with as much medication as needed without the fear of arrest. The Drug Enforcement Administration issued pain management guidelines in August 2004, prominently displayed on their website as “frequently asked questions.” These guidelines were negotiated by the DEA and pain management specialists in order to end the controversy over the arrests of hundreds of pain specialists who prescribe powerful opiates. However, less than two months after the guidelines were published they were removed from the DEA website, replaced by the explanation that the document “contained misstatements” and “was not approved as an official statement of the agency.” The move came after the legal defense team of Dr. William Hurwitz, a physician accused of drugtrafficking, sought to use the guidelines as evidence.82

Increases in Drug-Related Harms

Drug prohibition has brought with it impurity of substances, imprecise dosages and extreme modes of ingestion. 83 Without regulation, the substances are produced by people who are trying to turn a profit and are often “cut” with other drugs or substances in order to increase the amount of product. People who use the drugs also tend to use the highest dosage possible because of the inflated price and the risk they took to get the drug. A similar phenomenon occurred during alcohol prohibition in the 1920s, as “hard” liquor was more popular to sell than beer because it could turn a higher profit due to alcohol content-determined price, it could be hidden and transported easier and it could be preserved indefinitely whereas beer spoiled easily.84

With the prohibition on drugs also comes an increase in blood-borne illnesses such as HIV and Hepatitis A, B and C as a result of needle sharing by drug users. It is further exacerbated by the large numbers of prisoners with these diseases in overcrowded facilities. This has also led to a resurgence of tuberculosis in jails and prisons. In 1988 the rate of TB in the general population was 13.7 per 100,000, whereas. In correctional facilities the case rates have been as high as 400 to 500 per 100,000.85 When these prisoners are released, they bring these diseases with them back to the community.

State Administration of the Current Drug Control System

Uniform Controlled Substances Act.

Most of the state controlled substances laws in effect today are based on the 1970 model law called the Uniform Controlled Substances Act (UCSA).86 The UCSA follows the same approach as federal law, seeking to enforce drug prohibition through the use of criminal sanctions. Facing enormous budget pressures, however, many states have made innovations within the federal framework of drug prohibition and criminal enforcement to find alternatives to the expensive use of incarceration.

Drug Courts and Treatment Alternatives

There have been numerous well-publicized efforts around the country to move drug policy away from a purely punitive purpose, although all such efforts have remained within the confines of the criminal justice system. 87 These reforms have had positive outcomes for participants and have ameliorated some negative impacts of current drug policy, but none have been able to resolve the problems arising from criminalization.

“Drug courts” are the most prominent drug policy innovation recently, having helped states and localities to realize cost savings and having reduced rates of recidivism and prohibited drug use among participants, at least in the short term. 88 The drug court model, however, while stressing rehabilitation over retribution, still does not represent a fundamental departure from the federal legal framework. The use and sale of selected psychoactive substances, which are prohibited and punished under federal law, continue to be uniformly prohibited and punished in all of the states, and the federally-subsidized drug courts use the threat of criminal sanctions to coerce abstinence, sanctions which are often imposed; many, if not most, drug court participants are still confined to jail or prison for failure to complete treatment requirements.89

If insightfully and compassionately administered, drug courts can make a large contribution to rehabilitation of addicts, reduction of crime, and avoid the economic and societal costs of unnecessary imprisonments. However, drug courts are not a panacea and do present some real dangers to the participants and the general public:

1) People who are forced into treatment may not actually need it; they may just be people who use drugs in a non-problematic way who happened to get arrested.

2) Providing coerced treatment, at a time when the needs for voluntary treatments are not being met, creates the strange circumstance of someone needing to get arrested to get treatment.

3) Some drug courts rely on abstinence-based treatment. For example, methadone may not be allowed to heroin addicts. In addition, some may rely heavily on urine testing rather than focus on whether the person is succeeding in employment, education or family relationships.

4) Drug courts often mandate twelve-step treatment programs that some believe to be an infringement on religious freedom.

5) Drug courts invade the confidentiality of patient and health care provider.

The health care provider's client is really the court, prosecutor and probation officer, rather than the person who is receiving drug treatment.

6) Drug courts are creating a separate system of justice for drug offenders not based on the time honored adversarial roles of defense attorney, prosecutor and judge. Therefore, a relapsed patient may end up with much harsher penalties than from a regular court.

The intent to emphasize treatment is commendable, as long as the approach also mitigates potential harm.

Even if all drug courts were to avoid such pitfalls, such programs are currently available only to a few defendants, although court-supervised treatment programs are now proliferating rapidly across the country. 90 Nevertheless, even if such programs were widely available, drug courts are still powerless to rein in the illegal markets for the prohibited psychoactive substances, markets that are left unregulated and in the hands of criminal enterprises that reap enormous profits and that often control their interests through violence.

Numerous states have enacted measures to provide drug treatment in lieu of incarceration, most prominently in California, where voters passed Proposition 36, the Substance Abuse and Crime Prevention Act of 2000, which allows first and second time non-violent, simple drug possession offenders the opportunity to receive substance abuse treatment instead of incarceration. 91 In the first two years of the law’s enactment, 66,000 drug offenders were diverted, many receiving treatment for the first time.92 Across the United States, court-supervised drug treatment programs have spread quickly, offering defendants alternatives to incarceration and offering local jurisdictions the opportunity to save court and detention costs.93

It is important to note that the diversion of drug offenders into treatment, although considered an “innovation” in drug policy, still falls squarely into the strict prohibition model, whereby individuals are subject to the control of the criminal justice system and total abstinence from drug use is the only permissible outcome.

De-policing

The “de-policing” concept is being employed to mandate that police officers refrain from actively targeting certain crimes involving non-violent drug offenses so that they may have more time to pursue crimes the public deems more serious to their safety. In 2003, voters in Seattle, Washington passed Initiative 75, which instructs police to turn a blind eye to possession or use of small amounts of cannabis by adults.94 As a result the number of people arrested for cannabis fell, with 18 arrests in the first half of 2004, compared with 70 arrests in the same time period one year prior. At the same time, there has been no evidence of widespread public consumption of cannabis as a result of the measure.95

CURRENT STATE-LEVEL MODELS FOR REGULATING DRUGS

As stated above and by legions of commentators, the current, prohibition-based system of “regulating” psychoactive substances has lent itself to criminal activity, erosion of public health, skyrocketing public costs, compromises in civil rights and the excessive punishment of the poor, among other adverse effects. However, there exist systems of regulation for certain other substances that could serve as potential models for regulating those substances now subject to absolute prohibition. There is also a range of legal remedies other than criminal sanctions that could be considered when addressing the harms associated with the use of psychoactive substances.

Regulatory Mechanisms for Currently Legal Substances

The most well-known regulatory systems for other psychoactive substances are for alcohol, tobacco and pharmaceuticals. These substances are each regulated in different manners so that they may only be obtained by certain individuals in certain ways, according to how the government deems it most appropriate for the particular substance.

Alcohol

From 1920 to 1933 the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution prohibited the manufacture, transportation and sale of alcohol. After prohibition proved to be a failure, the 18th Amendment and gave the states the right to make their own laws regarding alcohol. Today every state, and the District of Columbia, has its own liquor control board that regulates alcohol within each state.96 The federal agency, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, serves as the law enforcement agency for the trafficking of illegal tobacco and alcohol by criminal and terrorist organizations, and to assist local, state and other federal law enforcement and tax agencies with investigations of interstate trafficking of tobacco and alcohol.97

States license alcohol manufacturers, distributors and retailers and enforce liquor laws and rules. The state liquor control boards regulate the manufacture, distribution and sale of alcohol. Eighteen states are “control states,” a model in which the state is directly involved in the distribution and/or sale of liquor. The original purpose of establishing a control model was so the state could control the availability of alcohol through factors such as restricted number of outlets, no advertising and using state employees to sell spirits who have no financial incentive to sell or promote sales.

Some laws for alcohol vary even within states, as counties may have their own regulations. For example, the state of Texas has a patchwork of wet and dry counties, and counties that are a confusing mixture of both. At some restaurants in those dry counties patrons must become “members” in order to purchase alcohol, leading to high administrative costs for the restaurants. Supermarkets are also losing alcohol revenues, so the state is in the process of trying to ease those restrictions that are hurting businesses financially. Texas is not alone in having a confusing scheme of alcohol laws.98

Washington State Liquor Control Board

Washington is considered to be one of the strictest “control” states in the country, a system overseen by the Washington State Liquor Control Board.99 is run by a three member Board appointed by the Governor for six-year terms. There are nine divisions covering the agency’s three primary functions: licensing, enforcement and retail services.

The Licensing Division licenses distributors and retail outlets, e.g., restaurants, taverns, grocery stores and breweries, and regulates non-retail licensees such as manufacturers, distributors and importers. The Licensing Division also advises manufacturers, distributors and retailers on advertising and promotion laws and rules, and approves labels for all beer and wine sold in the state. Finally, the division manages the permit program for bartenders and alcohol servers.

The Enforcement and Education Division has 74 liquor and tobacco enforcement agents throughout the state of Washington, who visit restaurants and bars to ensure that minors are not being served and to prevent over-service. The agents also check grocery and convenience stores to ensure they do not sell to minors, and the agents also educate licensees on liquor and tobacco laws and rules.

Retail services of the Washington State Liquor Control Board include purchasing, distribution and retail stores. The Purchasing Division recommends new product listings and de-listings, places orders with suppliers, fills special orders, and negotiates military contracts and tribal vendor agreements. The Liquor Control Board is the sole wholesaler of spirits in the state and runs a distribution center. Liquor is shipped to stores by independent carriers which operates on a bailment system (the supplier owns the product until it leaves the distribution center) The Retail Services Division manages the operation of 157 state-run stores in larger communities and 155 contract liquor stores in smaller communities. State-run stores account for approximately 83% of the total sales. Contract store managers are paid on commission.

The Liquor Control Board sets the marked-up price for spirits sold in state and contract liquor stores. Profits from the sale of spirits and state excise tax on beer, wine and spirits are distributed to the State General Fund; city, county and border areas; health services; education and prevention; and research.

Tobacco

Tobacco production, advertising, packaging, sale and distribution is regulated by the federal government but states may impose taxes and enact laws restricting use by minors and setting limits on places where tobacco may be smoked. The Federal Trade Commission regulates tobacco advertising and warning labels, and the Department of Agriculture regulates the farming of tobacco. The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives under the U.S. Department of Justice enforces the regulations in association with other federal, state, local and international law enforcement entities. In Washington State, the Liquor Control Board’s Enforcement and Education Division enforces tobacco regulations in addition to alcohol, provides education on tobacco laws, and deters the sale of untaxed cigarettes. There are no laws requiring the disclosure of ingredients in tobacco products and no requirement to warn of carcinogens.100

Tobacco products and advertising were on the verge of being regulated by the Food and Drug Administration after the U.S. Senate passed a bill in mid-2004, but the leadership in the U.S. House of Representatives blocked the action. Health care advocates are pushing for FDA oversight of tobacco after an adverse U.S. Supreme Court decision in 2000 declaring the agency's earlier claim of authority over tobacco unconstitutional.101 If approved, the bill would have allowed the FDA to regulate the sale, distribution, labeling and advertising of cigarettes and smokeless tobacco, as well as the ability to require manufacturers to better disclose the contents and consequences of their products in new, stronger warning labels on packages.102

Pharmaceuticals and the “Gray Market”

Pharmaceuticals are regulated federally by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the Consumer Products Safety Commission (CPSC), the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). Also operating on the national level is the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO), a non-profit organization that evaluates and accredits health care organizations and programs in the U.S. In the state of Washington pharmaceuticals are regulated by the Board of Pharmacy, the Department of Social and Health Services, the Department of Ecology, and the Department of Labor and Industries.

The DEA regulates the manufacture, distribution, possession, storage and disposal of pharmaceuticals. The regulation of pharmaceuticals is a closed system where everyone must register with the DEA, including manufacturers, distributors, prescribers and pharmacies, and records, prescriptions and order forms are all required. In the state of Washington there is a Board of Pharmacy that oversees pharmaceuticals in the state under the Legend Drug Act103 and the Uniform Controlled Substances Act,104 and there are professional boards that oversee professionals who work with and around pharmaceuticals.

Drugs are classified as over the counter (OTC), prescription (legend drugs), or controlled substances. There is no supervision for provision of OTC drugs, while prescription drugs can only be used under authorization by physician under federal law. Controlled substances are classified into five schedules under the Controlled Substance Act according to potential for abuse. The DEA issues licenses to physicians to prescribe controlled substances. While the prohibited substances under Schedule I cannot be prescribed, as they have no approved medical use, substances under Schedule II can be prescribed with non-refillable written prescriptions. Substances in the lower schedules are less strictly controlled, with some Schedule V substances available over the counter.

Prescription authority must be authorized under state law, which is governed by the Legend Drug Act, Food Drug and Cosmetic Act, Uniform Controlled Substances Act, Profession’s Practice Act, and rules adopted under these laws. Physicians with the degrees of M.D. and D.O. (osteopaths) have no restrictions on their prescribing authority, while dentists, nurse practitioners, nurse anesthetists, physician assistants, optometrists, naturopaths and veterinarians all have restrictions on their prescribing authority. Drugs are used or stored by pharmacies, drug wholesalers, hospitals, outpatient surgery centers, doctors’ offices or clinics, nursing homes and adult family homes and boarding homes.

The FDA regulates the initial approval of a drug and the manufacture and distribution. The decision whether or not to make a drug prescription or over the counter is not always based strictly on science. Advisory committees to the FDA recommend whether or not to allow a prescription drug to be sold over the counter before the FDA’s commissioner decides to accept or reject the finding, but such a decision involves more than science or patient safety, as influences like marketing and financial considerations, politics, doctors’ concerns and consumer psychology may also contribute. Doctors often prefer prescriptions for drugs that are generally safe enough to be over the counter because they would like the ability to monitor their patients’ use of the drugs and they are vocal about this concern whenever a drug comes up for consideration as an over-thecounter option. Although it is reasonable for doctors to be concerned for their patients’ safety, some are concerned that it could prevent people from having easier access to medicines they need.105

The “gray market” is the term used to describe the market in diverted legal prescription drugs. These drugs are diverted not only by drug abusers, but by licensed health care professionals and others at any site where the drugs are stored, administered, prescribed or dispensed. The manners in which drugs are diverted include theft, armed robbery, burglary, record alteration, prescription forgery, “wastage” and substitution. For example, from January through February of 2003, drug thefts from pharmacies in the state of Washington included four armed robberies, four burglaries, eight employee thefts and four lost-in-transits, totaling 28,925 dosage units at a cost of $20,893. The main drug implicated was Oxycontin. In 2002, the Washington State Pharmacy Board investigated 130 nurses, 6 pharmacists, 13 pharmacy techs and one pharmacy intern for diversion. These investigations may lead to criminal charges or, at the very least, administrative proceedings by their respective professional boards, but the Pharmacy Board prefers to employ the “medical model” rather than the “criminal model.” The boards send violators to treatment, withhold their licenses until required follow-ups with aftercare and meetings, and monitor them for up to five years with urinalysis.106

Existing Legal Remedies – Civil and Other Non-Criminal Sanctions

Civil Proceedings: The Other “Drug Courts”

Courts hearing certain types of civil cases already operate as a parallel system of “drug courts.” The civil courts are concerned with assessing and addressing conduct that adversely affects others – particularly children – and such conduct is often associated with substance abuse. Compared with the criminal courts, the civil courts are charged with evaluating harm and finding remedies, rather than determining guilt and meting out punishment, and are therefore more remedial and therapeutic in nature.107

Civil courts are regularly called upon to evaluate and remedy the impacts of drug use in family law cases involving divorce, child custody, child support, and child welfare. Drug use might be addressed in the course of a tort claim, employment law case or civil commitment proceeding. The following is a partial list of civil proceedings in which drug use is already being addressed outside of the criminal justice system: Involuntary Commitment,108 Civil Commitment,109 Domestic Relations,110 Child Welfare,111 Child Dependency (order to substance abuse treatment),112 Child Dependency (violation of substance abuse treatment order,113 and the Uniform Controlled Substances Act involving a tort cause of action by a parent for sale or transfer of controlled substances to a minor.114

Existing law even protects drug users from unintentionally entering into a marriage under the influence of alcohol and/or other mind-altering substances.115 In Alaska, a drug dealer is strictly liable to the recipient of the drugs or another person if the recipient causes civil damages while under the influence of the drugs.116

Civil Contempt and Remedial Sanctions: Coercion With a Purpose

Proponents of the current, criminal justice-based approach to substance abuse argue that the threat of jail or prison is necessary to coerce people into treatment. It is important to acknowledge, however, that contact with the criminal justice system also results in the assignment of a criminal record, the denial of a host of services, voting disqualification and other prejudicial effects, all of which are counterproductive to the goals of drug treatment. The proper venue for the state to address these questions is in the civil context – and orders in civil proceedings are ultimately enforced by the court’s power to find a party in contempt. Civil courts have inherent power to coerce compliance

– the so-called “hammer” – and impose sanctions as punitive or remedial measures.117

Professional Sanctions

Professional organizations have their own punishment for members who are not performing to the standards of their professions. For example, attorneys must follow the Rules of Professional Conduct as enforced by the Washington State Bar Association and the Washington State Medical Association has the Principles of Medical Ethics. Failure to abide by these ethics rules subjects the professional to sanctions governed by their respective associations.

ALTERNATIVE MODELS OF DRUG CONTROL

The public debate around drug “legalization” has generally assumed that there are only two policy options: criminalization or legalization. However, there is a wide spectrum of options available for systems of regulation beyond mere criminalization. Many ideas have been already been proposed for alternative models to the current system of drug control. Some are simply general frameworks of how drugs should be regulated or provided in an effort to undercut the black market. Others have been proposed in the form of legislation. Some countries have already implemented some alternatives to prohibition in the attempt to combat more effectively the harms linked to drug abuse.

General Frameworks

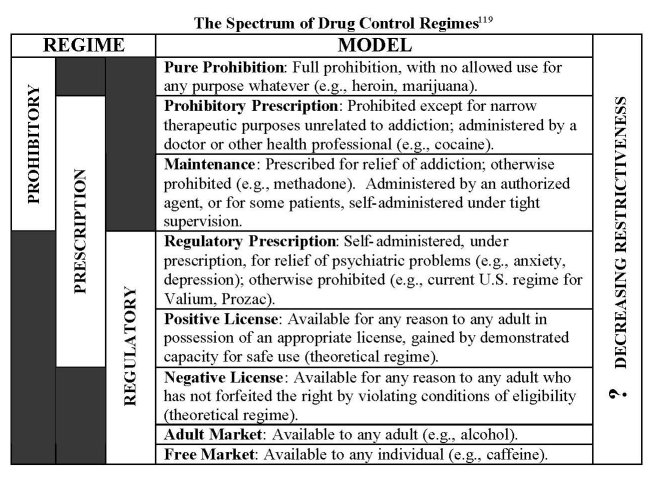

Leading drug policy researchers, Peter Reuter and Robert MacCoun, have outlined the spectrum of possible drug control regimes.118 Such regimes include pure prohibition, prohibitory prescription, maintenance, regulatory prescription, positive license, negative license, adult market, and the free market:

Report from Britain– After the War on Drugs: Options for Control

Transform, a drug policy think tank in the United Kingdom, released a report in October 2004 setting forth models for a new drug control regime.120 The report, which was released with the support of former police officers and Members of Parliament,121 calls for the control and regulation of drugs and lays out a suggested legal framework based on an examination of the existing models in Britain under which drugs are produced, existing ways in which drugs are supplied and new drug supply options.

The Transform report breaks down the existing options for drug production into: 1) pharmaceutical drugs; 2) non-pharmaceutical drugs ; and 3) unlicensed production. One example of a pharmaceutical drug is diamorphine, or heroin, which is still a pharmaceutical drug in the United Kingdom, the production of which is licensed and regulated.122 More than half of the global opium poppy production is for the legal medical market.

Non-pharmaceutical drugs include alcohol, tobacco and caffeine. In Britain alcohol and tobacco are produced and imported under domestic and international licensing agreements and policed and taxed by Customs and Excise. Unlike tobacco, alcohol is a food/beverage besides being a drug and is therefore subject to various standards legislation. While home production of alcohol is not licensed, tobacco could be licensed and taxed for personal production but rarely is, thus making it de facto unlicensed.

Caffeine is unlicensed, subject only to food and drink regulations. Other psychoactive substances, such as psychedelic mushrooms, khat, “herbal remedies” and “food supplements” are available in Britain but produced without any regulation or control.

The supply of drugs occurs through prescription, pharmacy sales, licensed sales, licensed premises for consumption and unlicensed sales. In the prescription model, drugs are prescribed by a licensed doctor and dispensed by a licensed pharmacist. Further restrictions to the prescription model allow injectable diamorphine (heroin) to be prescribed only by a doctor with a specialized license, the occasional requirement that methadone be consumed in the pharmacy and the dispensing and injecting of diamorphine under medical supervision in a specialized venue, as occurs in Switzerland.

In the pharmacy sales model, pharmacists make sales behind the counter with the responsibility to make restrictions according to age, quantity and concerns regarding misuse. The pharmacist is qualified to offer advice and health and safety information.

Licensed sales include drugs such as alcohol and tobacco where licensed sellers are restricted to whom they can sell based on age and the hours in which they may sell, and licensing authorities oversee the regulations of these drugs. A step beyond this is licensed premises for sale and consumption, where the drug, mostly alcohol, is consumed at the sale site, and there is the added restriction of intoxication of the purchaser.

The final existing supply option is unlicensed sales, where there are no existing controls at point of purchase for some intoxicants. Mushroom vendors are starting to get a second look by police and Customs and Excise, and some vendors voluntarily have restrictions on the basis of age. Also, sales of certain solvents and inhalants are prohibited to children.

The Transform report suggests the establishment of new supply options, built on existing models, including specialized pharmacists and licensed users with membership based licensed premises. Specialized pharmacists would be a combination of pharmacist and “drugs worker,” licensed to vend certain drugs to “recreational” users, and trained to recognize problematic use, provide safety information and make referrals to social services. Membership-based licensed premises are similar to the licensed premises for consumption already existing in many countries, with the caveat that drug purchase and consumption would require a membership with various conditions and restrictions.

Regulatory Options

Mark Haden, clinical supervisor of Addiction Services at the Vancouver Coastal Health Authority, has examined the various ways in which drugs could be regulated:

1. “Free market” legalization. Drugs are sold in the “free market.” Promotion, advertising and finding ways to promote sales and use of the substances would be allowed.

2. Legalization with “product” restrictions . Restrictions on manufacturers, packagers, distributors, wholesalers and retailers.

3. Market Regulation. Restrictions on the product and purchaser, discussed in further detail below.

4. Allow drugs to be available on prescription. All physicians could be allowed to prescribe currently illicit substances for medical or maintenance purposes.

5. Decriminalization. The removal of criminal sanctions for personal use only. This does not provide for legal options for how to obtain drugs, so there is still unregulated access to drugs of unknown purity and potency.

6. De facto decriminalization or de facto legalization. Collectively agreeing to ignore existing laws without changing them – an option for establishing a transitional period when testing out which policy options to consider.

7. Depenalization. Penalties for possession are significantly reduced and would include discharges, diversion to treatment instead of jail for possession of large amounts and trafficking, and “parking ticket” status for possession of small amounts for personal consumption.

8. Criminalization. Continuing to enforce all existing laws prohibiting certain drugs through the use of criminal sanctions.123

The “Market Regulation” model, in which access to substances would be regulated by placing restrictions on the purchaser or consumer, is particularly instructive. This model includes 14 different regulatory mechanisms, which are not necessarily mutually exclusive:

1. Age of purchaser. There are currently restrictions to access of alcohol and tobacco based on age, but there is no control of the age when illegal drugs can be purchased. Drug dealers today do not ask their customers for age identification.

2. Degree of intoxication of purchaser. In Canada the sale of alcohol is restricted based on the degree of intoxication of the purchaser. Sellers can refuse to sell to a customer whom they perceive to be engaging in high-risk substance using behavior.

3. Volume rationing. Quantities would be limited to a certain amount deemed appropriate for personal consumption so that purchasers would not be selling the product on the black market or using an unsafe amount.

4. Proof of dependence prior to purchase. Purchaser must have been assessed by a health worker to be dependent and then allowed to use the rationed amount in a designated space.

5. Proof of “need” in order to purchase. Beyond those drugs on which people are dependent, other drugs such as LSD and Ecstasy, which have been shown to have potential psychotherapeutic benefits when used in controlled therapeutic environments, could be used with registered and trained psychiatrists and psychologists.

6. Required training for purchasers . Training programs could provide information to drug users about addiction, treatment services and other public health issues, like sexually transmitted diseases and blood-borne illnesses. The programs could provide the knowledge and skills aimed at discouraging drug use, reducing the amount of drug use, and reducing the harm of drug use. Program graduates would receive a certificate they would be required to show prior to purchase.

7. Registrations of purchasers . This would allow the purchasers to be tracked for “engagement” and health education. It might also discourage individuals from wanting to participate.

8. Licensing of users . Like licenses for new motor vehicle drivers that restricts where and when they drive and who they are permitted to drive with, these licenses would control time, place and associations for new substance users. This would be a graduated program with demonstrated responsible, non-harmful drug use. The license could be given demerit points or suspended based on infractions such as providing substances to non-licensed users, driving under influence or public intoxication. The licenses could also specify different levels of access to various substances based on levels of training and experience. People in some professions, like airplane pilots or taxi drivers, could be restricted from obtaining licenses to purchase long-acting drugs that impair motor skills.

9. Proof of residency with purchase. Some societies have gone through a process of developing “culturally specific social controlling mechanisms” that form over time a certain amount of relatively healthy, unproblematic relationships with substances. “Drug tourists” who have not been integrated into this culture may behave in problematic ways that do not adhere to the local restraining social practices. Therefore, purchasers may be restricted to residents of a country, state/province, city or neighborhood.

10. Limitations in allowed locations for use. Alcohol is often restricted for public consumption and some public locations do not allow tobacco consumption. Locations for substance use could vary based on the potential for harm. Options of locations include supervised injection rooms for injected drugs, supervised consumption rooms for the smoking of heroin and cocaine, and home use for weaker drugs of known purity and quantity.

11. Need to pass a test of knowledge prior to purchase. A short test could be administered at the distribution point to demonstrate to the staff that the purchaser has the required knowledge of safe use of the substance that is likely to minimize harm.

12. Tracking of consumption habits. Registered purchasers would have the volume and frequency of purchasing tracked. This could be used to instigate “health interventions” by health professionals who could register their concerns with the user and offer assistance if a problem is identified. The tracking may be a deterrent to use, as well as a possible increase in price of the substance once the user has passed a certain volume threshold.

13. Required membership in group prior to purchase. Drug users can belong to advocacy or union groups that would act similar to existing professional regulatory bodies that provide practice guidelines for their members. If the user acts outside of the norms of the discipline, the group can refuse membership. The norms are enforced through a variety of peer processes and education.

14. Shared responsibility between the provider and the consumer. Sellers could be partially responsible for the behaviors of the consumers. To that end, the sellers would monitor the environment where the drug is used and restrict sales based on the behavior of the consumers. Proprietors could be held responsible through fines or license revocations for automobile accidents or other socially destructive incidents for a specified period of time after the drug is consumed. The consumer would not be absolved of responsibility but a balance would be established where the consumer and seller were both liable.124

A Variety of Ideas

The Economist published its “survey of illegal drugs” in its July 28, 2001 issue. In the section entitled, “Set it free,” the Editors write that “the best answer is to move slowly but firmly to dismantle the edifice of enforcement.” This could be achieved through government distribution, like alcohol in Scandinavia, or through the private sector with tough bans on advertising and full legal liability. Sales could be made through pharmacies or mail-order, and individual states could decide whether to allow public sale. The result would arguably be the ability to regulate drug quality, treat the health of users and only punish drug users who commit crimes against people or property.125

John P. Morgan, M.D., a physician and professor of pharmacology at the City University of New York Medical School, advocated legalizing cannabis in his essay, “Prohibition is Perverse Policy,” with the requirement that “a cigarette weighing 500mg to 1.0 gram of marijuana would deliver 12 to 20mg of delta-9-THC.” Dr. Morgan would also set the purchase age at 18, have strict penalties for driving under the influence of cannabis, and “encourage development of other delivery systems so combustion and inhalation were unnecessary.”126

Todd Austin Brenner, a managing partner at the law firm Brenner, Brown, Golian and McCaffrey Co. in Ohio, supports phased legalization, cannabis first, in a manner very similar to alcohol regulation, proceeding then to all narcotics. Some drugs such as heroin and crack would be banned from sale but available free of charge at clinics where registered addicts could obtain them. Brenner speculates that more education and emphasis on health-consciousness and value of personal choice will reduce problematic drug use.127

Taylor Branch, a national authority on America’s civil rights movement, also espouses taxing and regulating drugs. His plan would license private distributors carefully and tax the drugs as heavily as possible, ideally to the point just short of creating a criminal black market. There would be no prescription requirement and a ban on commercial advertising for harmful drugs, even though their sale would be legal. Police powers would be concentrated on two tasks: prohibiting sales to children and enforcing strict sanctions against those who cause injury to others while under the influence. Branch feels that people do not believe government warnings about psychoactive drugs, and getting the public to trust such warnings would be an important step toward reducing use. For example, the rate of tobacco smoking has dropped dramatically because people came to accept the health warnings.128

Richard B. Karel, in his “Model Legalization Proposal,” argues that crack cocaine should not be legalized, hoping that its use will be substituted by other available forms of cocaine, including a cocaine chewing gum similar to nicotine gum used to help smokers to quit. He also sees the benefit of distributing cocaine in a clinical setting, but also allowing an ATM-type system where users would need to acquire a card that only allowed them to acquire the drug every 48 to 72 hours. He mentions that while opium was used in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to treat alcoholics, U.S. drug policy of banning opium smoking has now led to dangerous forms of opiate use, such as intravenous heroin. Therefore, Karel believes that smokable opium should be made available in a similar fashion as the cocaine gum with ATM cards. PCP should remain illegal, hopefully substituted by other drugs that are available. Pyschedelics should be available to whoever can demonstrate the knowledge as to their effects, through such methods as a written examination, screening test and interview. 129

Arnold Trebach, Professor Emeritus at the American University in Washington,

D.C. and former president of the Drug Policy Foundation (now Drug Policy Alliance), advocates for the immediate repeal of drug prohibition, much in the way alcohol prohibition ended in the 1930s. Trebach believes that all currently illicit drugs should be treated the way alcohol is treated and wishes to turn back the clock to before opium smoking was outlawed, with sensible regulations regarding purity, labeling, places and hours of sale, and age limits for purchasers.130

Ethan Nadelmann, the executive director of the Drug Policy Alliance, has spent decades writing about alternatives to drug prohibition, and proposed a model whereby the government would distribute drugs through a mail-order system, also known as the “right of access” model. Local jurisdictions could still prohibit the sale and public consumption of drugs but would have to acknowledge the right of access for all adults. He believes this system would make it difficult for people to obtain the drugs despite their legal availability, would be easy to transition to from prohibition, and would avoid the principal problem of the “supermarket model” – the potential for a substantial increase in amount and diversity of psychoactive drug consumption. 131

Specific Models

Safe Administration and Prescription of “Hard” Drugs

A model now in effect in Canada, Switzerland and many other countries in Europe is the safe administration of “hard” drugs, particularly heroin. 132 While some worry about the diversion of drugs from the clinics, it has been shown that illegally distributed methadone has come from its use as a prescription painkiller, not diversion from opioid treatment programs, programs comparable to the heroin maintenance programs.133

Numerous countries have also instituted opiate prescription programs in which hard-core drug addicts are brought indoors into medically-supervised facilities and stabilized with controlled doses that are free of charge. These programs have brought about very promising outcomes, including: reductions in overdose deaths; reductions in

the transmission of disease; reductions in economic crimes related to addiction; reductions in levels of public disorder; reductions in the quantity of drugs used; elimination of drug habits altogether for 20% of participants; stabilization of the health of participants; increased employment rates of participants; law enforcement support; and a changed culture in which addictive drugs like heroin lose their cachet and are considered to be medication for the sick, resulting in declining rates of first-time use of such drugs.134

The opiate prescription programs in Europe and Canada are made possible only through specific, carefully circumscribed exemptions from the prohibition-based legal framework and not through any fundamental change of that framework.

Past Proposed Legislation

There has already been legislation proposed, or at least drafted, in Congress and in state legislatures. While some have only addressed cannabis, the scope of other bills has extended to all currently-prohibited drugs. One of the first bills to begin addressing legalization was introduced in the New York senate in 1971 by Senator Franz Leichter.135 The bill established a Marijuana Control Authority to license and regulate commerce in cannabis, similar to alcohol regulation but forbidding advertising. The bill was introduced throughout the 1970s and attracted a number of co-sponsors. One co-sponsor, Senator Joseph L. Galiber, introduced his own bill in 1989, expanding the scope of the Leichter bill to include all drugs. The bill was entitled, “A Bill to Make All Illegal Drugs as Legal as Alcohol.”136 Under the Galiber bill, a State Controlled Substances Authority would be authorized to make all necessary rules for drug production, distribution and sales. Doctors and pharmacists would be licensed to sell all controlled substances. Senator Galiber, disturbed by the harsh ineffectiveness of the so-called “Rockefeller drug laws” in New York, continued to introduce versions of his bill throughout the 1990s until his death.

The Cannabis Revenue and Education Act was introduced in 1981 in Massachusetts to regulate the commercial production and distribution of cannabis.137 The Act would impose a tax based on THC content, with half of the net tax proceeds going toward a Cannabis Education Trust, set up to educate the public about marijuana abuse.

The Cannabis Revenue Act (CRA), drafted in the U.S. Congress in 1982, was the only bill at the federal level to regulate and tax cannabis. The bill would have allowed each state to choose one of three options for legalizing cannabis: 1) retaining prohibition; 2) be part of the federal regulation and taxation scheme with only laws to handle driving under the influence and distribution to minors; or 3) enact its own regulation and taxation scheme in addition to the federal one.138

Bills modeled on the federal CRA proposal were introduced in Oregon and Pennsylvania in 1983. The Oregon bill called for state-operated stores with the revenue earmarked for local school districts and law enforcement.139 The Pennsylvania bill would have put the regulation of the commercial cannabis industry under the Department of Agriculture with retail sales at state-owned liquor outlets, and personal cultivation and possession would allowed up to 2.2 pounds.140

A bill was introduced in the Missouri legislature in 1990 to license the production, distribution and sale of all drugs with strict limits on where drugs could be used, prohibiting drug use in bars, restaurants, offices, or cars, and in the presence of a minor under age 18, including in a private residence.141

An organization called Washington Citizens for Drug Policy Reform sponsored an initiative in 1993 to regulate cannabis in the state of Washington. Under Initiative 595, adults would have been allowed to grow and possess up to a “personal use quantity,” as determined by the courts, while cultivating, transporting and selling more than a personal use quantity would have required a license obtained from a cannabis control authority. There would be a $15 tax per ounce of cannabis “at standard cured moisture content.”142 The initiative allowed the retail sale of “cannabis products” made from the cannabis plant, opening the possibility of a wide variety of cannabis-based products like sodas, candy and teas. The initiative also made sure to mention federal intervention:

Sec. 21. State agencies shall refrain from enforcing any provision of United States criminal law not consistent with the purposes of this act, to avoid a waste of resources.143

Two drug regulation initiatives were put forward in Oregon in 1997. The Oregon Drug Control Amendment would have amended the state constitution to require that laws regulating controlled substances be passed and to prohibit laws prohibiting adult possession of controlled substances.144 The amendment included a section that prohibited the state from making a “net profit from the manufacture or sale of controlled substances.”145 The Oregon legislature was to enact a regulatory scheme to address the following issues:

a. A minimum legal age of not greater than 21 years;

b. Reasonable limits on adult personal possession;

c. Adequate public health and consumer safeguards;

d. Adequate manufacturing, price, import and export controls;

e. Penalties for violations, provisions for enforcement;

f. Exceptions for controlled scientific research;

g.Exceptions under medical and/or parental supervision;

h.Exceptions for traditional, spiritual practices;

i. A defined legal level of impairment;

j. Promotion of temperance, moderation and safety;

k.On-demand substance abuse and harm reduction programs.146

The other Oregon initiative in 1997, the Oregon Cannabis Tax Act (OCTA), would have renamed the Oregon Liquor Control Commission the “Oregon Intoxicant Control Commission” and would have charged the agency with licensing the cultivation and processing of cannabis. Licensees would only sell their crop to the Commission, who would sell it in OICC stores at a price that will “generate profits for revenue to be applied to the purposes [of the statute] and to minimize incentives to purchase cannabis elsewhere, to purchase cannabis for resale or for removal to other states.”147

The OCTA specified the distribution of profits from the sale of cannabis and issuance of licenses after administrative and enforcement costs: 90 percent to the general fund, 8 percent to the Department of Human Resources for treatment on demand programs, 1 percent “to create and fund an agricultural state committee for the promotion of Oregon hemp fiber, protein and oil crops and associated industries” and 1 percent to the school districts for drug education programs.148 The initiative list requirements for the curriculum of the drug education programs:

1. Emphasize a citizen’s rights and duties under out social compact and to explain to students how drug abusers might injure the rights of others by failing to fulfill such duties;

2. Persuade students to decline to consume intoxicants by providing them with accurate information about the threat intoxicants pose to their mental and physical developments; and

3. Persuade students that if, as adults, they choose to consume intoxicants, they must nevertheless responsibly fulfill all duties they owe others.149

As with Initiative 595 in Washington, the OCTA initiative also included a section addressing the problem of federal preemption:

Section 474.315. As funded by [this law], the Attorney General shall vigorously defend any person prosecuted for acts licensed under this chapter, propose a federal act to remove impediments to this chapter, deliver the proposed federal act to each member of Congress and urge adoption of the proposed federal act through all legal and appropriate means.150

1 U.N. ECON. & SOC. COUNCIL, SINGLE CONVENTION ON NARCOTIC DRUGS, 1961, U.N. Doc. UNE/CN.7/GP/1, U.N. Sales No. 62.XI.1 (1961); U.N. ECON. & SOC. COUNCIL, CONVENTION ON PSYCHOTROPIC SUBSTANCES, 1971, U.N. Sales No. E.78.XI.3 (1977); and U.N., CONVENTION AGAINST ILLICIT TRAFFIC IN NARCOTIC DRUGS AND PSYCHOTROPIC SUBSTANCES, 1988 (1988).

2 “Role of INCB,” International Narcotics Control Board, United Nations, at http://www.incb.org/e/index.htm.

3 Robert J. MacCoun and Peter Reuter (2001), Drug War Heresies, Cambridge University Press, p. 206.