7 Rules and Their Enforcement

| Books - Outsiders |

Drug Abuse

7 Rules and Their Enforcement

WE have considered some general characteristics of deviants and the processes by which they are labeled outsiders and come to view themselves as outsiders. We have looked at the cultures and typical career patterns of two outsider groups: marihuana users and dance musicians. It is now time to consider the other half of the equation: the people who make and enforce the rules to which outsiders fail to conform.

The question here is simply: when are rules made and enforced? I noted earlier that the existence of a rule does not automatically guarantee that it will be enforced. There are many variations in rule enforcement. We cannot account for rule enforcement by invoking some abstract group that is ever vigilant; we cannot say that "society" is harmed by every infraction and acts to restore the balance. We might posit, as one extreme, a group in which this was the case, in which all rules were absolutely and automatically enforced. But imagining such an extreme case only serves to make more clear the fact that social groups are ordinarily not like this. It is more typical for rules to be enforced only when something provokes enforcement. Enforcement, then, requires explanation.

The explanation rests on several premises. First, enforcement of a rule is an enterprising act. Someone—an entrepreneur—must take the initiative in punishing the culprit. Second, enforcement occurs when those who want the rule enforced publicly bring the infraction to the attention of others; an infraction cannot be ignored once it is made public. Put another way, enforcement occurs when someone blows the whistle. Third, people blow the whistle, making enforcement necessary, when they see some advantage in doing so. Personal interest prods them to take the initiative. Finally, the kind of personal interest that prompts enforcement varies with the complexity of the situation in which enforcement takes place. Let us consider several cases, noting the way personal interest, enterprise, and publicity interact with the complexity of the situation to produce both rule enforcement and the failure to enforce rules.

Recall Malinowski's example of the Trobriand Islander who had committed clan incest. Everyone knew what he was doing, but no one did anything about it. Then the girl's former lover, who had intended to marry her and thus felt personally aggrieved by her choice of another man, took matters into his own hands and publicly accused Kima'i of incest. In doing this he changed the situation so that Kima'i had no choice but to conunit suicide. Here, in a society of relatively simple structure, there is no conflict over the rule; everyone agrees that clan incest is wrong. Once personal interest evokes someone's initiative, he can guarantee enforcement by making the infraction public.

We find a similar lack of conflict over rule enforcement in the less organized situations of anonymous urban life. But the consequence is different, for the substance of people's agreement is that they will not call attention to or interfere in even the grossest violations of law. The city dweller minds his own business and does nothing about rule infractions unless it is his own business that is being interfered with. Simmel labeled the typical urban attitude "reserve":

If so many inner reactions were responses to the continuous external contacts with innumerable people as are those in the small town, where one knows almost everybody one meets and where one has a positive relation to almost everyone, one would be completely atomized internally and come to an unimaginable psychic state. Partly this psychological fact, partly the right to distrust which men have in the face of the touch-and-go elements of metropolitan life, necessitates our reserve. As a result of this reserve we frequently do not even know by sight those who have been our neighbors for years. And it is this reserve which in the eyes of the small-town people makes us appear to be cold and heartless. Indeed, if I do not deceive myself, the inner aspect of this outer reserve is not only indifference but, more often than we are aware, it is a slight aversion, a mutual strangeness and repulsion, which will break into hatred and fright at the moment of a closer contact, however caused. . . .

This reserve with its overtone of hidden aversion appears in turn as the form or the cloak of a more general mental phenomenon of the metropolis: it grants to the individual a kind and an amount of personal freedom which has no analogy whatsoever under other conditions.1

Several years ago, a national magazine published a series of pictures illustrating urban reserve. A man lay unconscious on a busy city street. Picture after picture showed pedestrians either ignoring his existence or noticing him and then turning aside to go about their business.

Reserve, while typically found in cities, is not characteristic of all urban life. Many urban areas—some slums and sections which are ethnically homogeneous—have something of the character of a small town; their inhabitants see everything that goes on in the neighborhood as their business. The urbanite displays his reserve most markedly in anonymous public areas —the Times Squares and State Streets—where he can feel that nothing that goes on is his responsibility and that there are professional law enforcers present whose job it is to deal with anything out of the ordinary. The agreement to ignore rule infractions rests in part on the knowledge that enforcement can be left to these professionals.

In more complexly structured situations, there is greater possibility of differing interpretations of the situation and possible conflict over the enforcement of rules. Where an organization contains two groups competing for power—as in industry, where managers and employees vie for control over the work situation—conflict may be chronic. Yet, precisely because the conflict is a persistent feature of the organization, it may never become open. Instead, the two groups, enmeshed in a situation that constrains both of them, see an advantage in allowing each other to commit certain infractions and do not blow the whistle.

Melville Dalton has studied systematic rule-breaking by employees of industrial organizations, department stores, and similar work establishments. He reports that employees frequently appropriate services and materials belonging to the organization for their own personal use, noting that this would ordinarily be regarded as theft. Management tries to stop this diversion of resources, but is seldom successful. They do not, however, ordinarily bring the matter to public attention. Among the examples of misappropriation of company resources Dalton cites are the following:

A foreman built a machine shop in his home, equipping it with expensive machinery taken from the shop in which he worked. The loot included a drill press, shaper, lathe and cutters and drills, bench equipment, and a grinding machine.

The foreman of the carpenter shop in a large factory, a European-born craftsman, spent most of his workday building household objects—baby beds, storm windows, tables, and similar custom-made items—for higher executives. In return, he received gifts of wine and dressed fowl.

An office worker did all her letter writing on the job, using company materials and stamps.

An X-ray technician in a hospital stole hams and canned food from the hospital and felt he was entitled to do so because of his low salary.

A retired industrial executive had an eleven unit aviary built in factory shops and installed in his home by factory personnel. Plant carpenters repaired and reconditioned the bird houses each spring.

Additions to the buildings of a local yacht club, many of whose members worked in the affected factories, were made by company workers on company time with company materials.

Heads of clothing departments in department stores marked goods they wanted for their personal use "damaged" and lowered the price accordingly. They also sold sale items above the sale price in order to accumulate a fund of money against which their appropriation of items for personal use could be charged.2

Dalton says that to call all these actions theft is to miss the point. In fact, he insists, management, even while officially condemning intramural theft, conspires in it; it is not a system of theft at all, but a system of rewards. People who appropriate services and materials belonging to the organization are really being rewarded unofficially for extraordinary contributions they make to the operation of the organization for which no legitimate system of rewards exists. The foreman who equipped his home machine shop from factory supplies was in fact being rewarded for giving up Catholicism and becoming a Mason in order to demonstrate his fitness for a supervisory position. The X-ray technician was allowed to steal food from the hospital because the hospital administration knew it was not paying him a salary sufficient to command his loyalty and hard work.3 The rules are not enforced because two competing power groups—management and workers—find mutual advantage in ignoring infractions.

Donald Roy has described similar evasions of rules in a machine shop, showing again that one group will not blow the whistle on another if they are both partners in a system characterized by a balance of power and interest. The machine operators Roy studied were paid by the piece, and rule-breaking occurred when they tried to "make out"—earn far more than their hourly base pay on given piece-work jobs. Frequently they could make out only by cutting corners and doing the job in a way forbidden by company rules (ignoring safety precautions or using tools and techniques not allowed in the job specifications).4 Roy describes a "shop syndicate," which cooperated with machine operators in evading formally established shop routines.5 Inspectors, tool-crib men, time-checkers, stock men, and set-up men all participated in helping the machinists make out.

For instance, machine operators were not supposed to keep tools at their machines that were not being used for the job they were then working on. Roy shows how, when this new rule was promulgated, tool-crib attendents first obeyed it. But they found that it led to a continually present crowd around the tool-crib window, a group of complaining men who made the attendant's workday difficult. Consequently, shortly after the rule was first announced, attendants began breaking it, letting men keep tools at their machine or wander in and out of the tool-crib as they pleased. By allowing the machinists to break the rule, tool-crib attendants eased their own situation; they were no longer annoyed by the complaints of disgruntled operators.

The problem of rule enforcement becomes more complicated when the situation contains several competing groups. Accommodation and compromise are more difficult, because there are more interests to be served, and conflict is more likely to be open and unresolved. Under these circumstances, access to the channels of publicity becomes an important variable, and those whose interest demands that rules not be enforced try to prevent news of infractions.

An apt example can be found in the role of the public prosecutor. One of his jobs is to supervise grand juries. Grand juries are convened to hear evidence and decide whether indictments should be returned against individuals said to have broken the law. Although they ordinarily confine themselves to cases the prosecutor presents to them, grand juries have the power to make investigations on their own and return indictments that have not been suggested by the prosecutor. Conscious of its mandate to protect the public interest, a grand jury may feel the prosecutor is hiding things from it.

And, indeed, the prosecutor may be hiding something. He may be a party to agreements made between politicians, police, and criminals to allow vice, gambling, and other forms of crime to operate; even if he is not directly involved, he may have political obligations to those who are. It is difficult to find a workable compromise between the interests of crime and corrupt politics and those of a grand jury determined to do its job, more difficult than it is to find satisfactory compromises between two power groups operating in the same factory.

The corrupt prosecutor, faced with this dilemma, attempts to play on the jury's ignorance of legal procedure. But occasionally one hears of a "runaway" grand jury, one which has overcome the prosecutor's resistance and begun to investigate those matters he wants it to stay away from. Exhibiting enterprise and generating embarrassing publicity, the runaway jury exposes infractions heretofore kept from public view and often provokes a widespread drive against corruption of all kinds. The existence of runaway grand juries reminds us that the function of the corrupt prosecutor is precisely to prevent them from occurring.

Enterprise, generated by personal interest, armed with publicity, and conditioned by the character of the organization, is thus the key variable in rule enforcement. Enterprise operates most immediately in a situation in which there is fundamental agreement on the rules to be enforced. A person with an interest to be served publicizes an infraction and action is taken; if no enterprising person appears, no action is taken. When two competing power groups exist in the same organization, enforcement will occur only when the systems of compromise that characterize their relationship break down; otherwise, everyone's interest is best served by allowing infractions to continue. In situations containing many competing interest groups, the outcome is variable, depending on the relative power of the groups involved and their access to channels of publicity. We will see the play of all these factors in a complex situation when we examine the history of the Marihuana Tax Act.

Stages of Enforcement

Before looking at that history, however, let us consider the problem of rule enforcement from another perspective. We have seen how the process by which rules are enforced varies in different kinds of social structures. Let us now add the dimension of time, and look briefly at the various stages through which enforcement of a rule goes—its natural history.

Natural history differs from history in being concerned with what is generic to a class of phenomena rather than what is unique in each instance. It seeks to discover what is typical of a class of events rather than what makes them differ—regularity rather than idiosyncrasy. Thus I will be concerned here with those features of the process by which rules are made and enforced that are generic to that process and constitute its distinctive insignia.

In considering the stages in the development of a rule and its enforcement, I will use a legal model. This should not be taken to mean that what I have to say applies only to legislation. The same processes occur in the development and enforcement of less formally constituted rules as well.

Specific rules find their beginnings in those vague and generalized statements of preference social scientists often call values. Scholars have proposed many varying definitions of value, but we need not enter that controversy here. The definition proposed by Talcort Parsons will serve as well as any:

An element of a shared symbolic system which serves as a criterion or standard for selection among the alternatives of orientation which are intrinsically open in a situation may be called a value.°

Equality, for example, is an American value. We prefer to treat people equally, without reference to the differences among them, when we can. Freedom of the individual is also an American value. We prefer to allow people to do what they wish, unless there are strong reasons to the contrary.

Values, however, are poor guides to action. The standards of selection they embody are general, telling us which of several alternative lines of action would be preferable, all other things being equal. But all other things are seldom equal in the concrete situations of everyday life. We find it difficult to relate the generalities of a value statement to the complex and specific details of everyday situations. We cannot easily and unambiguously relate the vague notion of equality to the concrete reality, so that it is hard to know what specific line of action the value would recommend in a given situation.

Another difficulty in using values as a guide to action lies in the fact that, because they are so vague and general, it is possible for us to hold conflicting values without being aware of the conflict. We become aware of their inadequacy as a basis for action when, in a moment of crisis, we realize that we cannot decide which of the conflicting courses of action recommended to us we should take. Thus, to take a specific example, we espouse the value of equality and this leads us to forbid racial segregation. But we also espouse the value of individual freedom, which inhibits us from interfering with people who practice segregation in their private lives. When a Negro who owns a sailboat announces, as one recently did, that no yacht club in the New York area will admit him as a member, we find that our values cannot help us decide what ought to be done about it. (Conflict also arises between specific rules, as when a state law forbids racial integration in public schools and Federal law demands it. But here determinate judicial procedures exist for resolving the conflict.)

Since values can furnish only a general guide to action and are not useful in deciding on courses of action in concrete situations, people develop specific rules more closely tied to the realities of everyday life. Values provide the major premises from which specific rules are deduced.

People shape values into specific rules in problematic situations. They perceive some area of their existence as troublesome or difficult, requiring action.' After considering the various values to which they subscribe, they select one or more of them as relevant to their difficulties and deduce from it a specific rule. The rule, framed to be consistent with the value, states with relative precision which actions are approved and which forbidden, the situations to which the rule is applicable, and the sanctions attached to breaking it.

The ideal type of a specific rule is a piece of carefully drawn legislation, well encrusted with judicial interpretation. Such a rule is not ambiguous. On the contrary, its provisions are precise; one knows quite accurately what he can and cannot do and what will happen if he does the wrong thing.

(This is an ideal type. Most rules are not so precise and foolproof; though they are far less ambiguous than values, they too may cause us difficulty in deciding on courses of action.)

Just because values are ambiguous and general, we can interpret them in various ways and deduce many kinds of rules from them. A rule may be consistent with a given value, but widely differing rules might also have been deduced from the same value. Furthermore, rules will not be deduced from values unless a problematic situation prompts someone to make the deduction. We may find that certain rules which seem to us to flow logically from a widely held value have not even been thought of by the people who hold the value, either because situations and problems calling for the rule have not arisen or because they are unaware that a problem exists. Again, a specific rule, if deduced from the general value, might conflict with other rules deduced from other values. The conflict, whether consciously known or only recognized implictly, may inhibit the creation of a particular rule. Rules do not flow automatically from values.

Because a rule may satisfy one interest and yet conflict with other interests of the group making it, care is usually taken in framing a rule to insure that it will accomplish only what it is supposed to and no more. Specific rules are fenced in with qualifications and exceptions, so that they will not interfere with values we deem important. The laws of obscenity are an example. The general intent of such laws is that matters which are morally repugnant shall not be broadcast publicly. But this conflicts with another important value, the value of free speech. In addition, it conflicts with the commercial and career interests of authors, playwrights, publishers, booksellers, and theatrical producers. Various adjustments and qualifications have been made so that the law as it now stands lacks the broad scope desired by those who deeply believe obscenity to be a harmful thing.

Specific rules may be embodied in legislation. They may simply be customary in a particular group, armed only with informal sanctions. Legal rules, naturally, are most likely to be precise and unambiguous; informal and customary rules are most likely to be vague and to have large areas in which various interpretations of them can be made.

But the natural history of a rule does not end with the deduction of a specific rule from a general value. The specific rule has still to be applied in particular instances to particular people. It must receive its final embodiment in particular acts of enforcement.

We have seen in an earlier chapter that acts of enforcement do not follow automatically on the infraction of a rule. Enforcement is selective, and selective differentially among kinds of people, at different times, and in different situations.

We can question whether all rules follow the sequence from general value through specific rule to particular act of enforcement. Values may contain an unused potential—rules not yet deduced which can, under the proper circumstances, grow into full-fledged specific rules. Similarly, many specific rules are never enforced. On the other hand, are there any rules which do not have their base in some general value? Or acts of enforcement which do not find their justification in some particular rule? Many rules, of course, are quite technical and may really be said to have their base, not in some general value, but rather in an effort to make peace between other and earlier rules. The specific rules governing securities transactions, for instance, are probably of this type. They do not seem so much an effort to implement a general value as an effort to regularize the workings of a complex institution. Similarly, we may find individual acts of enforcement based on rules invented at the moment solely to justify the act. Some of the informal and extralegal activities of policemen fall in this category.

If we recognize these instances as deviations from the natural history model, to how many of the things we might be interested in does the model actually apply? This is a question of fact, to be settled by research on various kinds of rules in various situations. At the least, we know that many rules go through this sequence. Furthermore, when the sequence is not followed originally, it is often filled in retroactively. That is, a rule may be drawn up simply to serve someone's special interest and a rationale for it later found in some general value. In the same way, a spontaneous act of enforcement may be legitimized by creating a rule to which it can be related. In these cases, the formal relation of general to specific is preserved, even though the time sequence has been altered.

If many rules get their form by moving through a sequence from general value to specific act of enforcement but movement through the sequence is not automatic or inevitable, we must, to account for steps in this sequence, focus on the entrepreneur, who sees to it that the movement takes place. If general values are made the basis for specific rules deduced from them, we must look for the person who made it his business to see that the rules were deduced. And if specific rules are applied to specific people in specific circumstances, we must look to see who it is that has made it his business to see that application and enforcement of the rules takes place. We will be concerned, then, with the entrepreneur, the circumstances in which he appears, and how he applies his enterprising instincts.

An Illustrative Case: The Marihuana Tax Act

It is generally assumed that the practice of smoking marihuana was imported into the United States from Mexico, by way of the southwestern states of Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas, all of which had sizable Spanish-speaking populations. People first began to notice marihuana use in the nineteen-twenties but, since it was a new phenomenon and one apparently confined to Mexican immigrants, did not express much concern about it. (The medical compound prepared from the marihuana plant had been known for some time, but was not often prescribed by U.S. physicians.) As late as 1930, only sixteen states had passed laws prohibiting the use of marihuana.

In 1937, however, the United States Congress passed the Marihuana Tax Act, designed to stamp out use of the drug. According to the theory outlined above, we should find in the history of this Act the story of an entrepreneur whose initiative and enterprise overcame public apathy and indifference and culminated in the passage of Federal legislation. Before turning to the history of the Act itself, we should perhaps look at the way similar substances had been treated in American law, in order to understand the context in which the attempt to suppress marihuana use proceeded.

The use of alcohol and opium in the United States had a long history, punctuated by attempts at suppression.8 Three values provided legitimacy for attempts to prevent the use of intoxicants and narcotics. One legitimizing value, a component of what has been called the Protestant Ethic, holds that the individual should exercise complete responsibility for what he does and what happens to him; he should never do anything that might cause loss of self-control. Alcohol and the opiate drugs, in varying degrees and ways, cause people to lose control of themselves; their use, therefore, is evil. A person intoxicated with alcohol often loses control over his physical activity; the centers of judgment in the brain are also affected. Users of opiates are more likely to be anesthetized and thus less likely to commit rash acts. But they become dependent on the drug to prevent withdrawal symptoms and in this sense have lost control of their actions; insofar as it is difficult to obtain the drug, they must subordinate other interests to its pursuit.

Another American value legitimized attempts to suppress the use of alcohol and opiates: disapproval of action taken solely to achieve states of ecstasy. Perhaps because of our strong cultural emphases on pragmatism and utilitarianism, Americans usually feel uneasy and ambivalent about ecstatic experiences of any kind. But we do not condemn ecstatic experience when it is the by-product or reward of actions we consider proper in their own right, such as hard work or religious fervor. It is only when people pursue ecstasy for its own sake that we condemn their action as a search for "illicit pleasure," an expression that has real meaning to us.

The third value which provided a basis for attempts at suppression was humanitarianism. Reformers believed that people enslaved by the use of alcohol and opium would benefit from laws making it impossible for them to give in to their weaknesses. The families of drunkards and drug addicts would likewise benefit.

These values provided the basis for specific rules. The Eighteenth Amendment and the Volstead Act forbade the importation of alcoholic beverages into the United States and their manufacture within the country. The Harrison Act in effect prohibited the use of opiate drugs for all but medical purposes.

In formulating these laws, care was taken not to interfere with what were regarded as the legitimate interests of other groups in the society. The Harrison Act, for instance, was so drawn as to allow medical personnel to continue using morphine and other opium derivatives for the relief of pain and such other medical purposes as seemed to them appropriate. Furthermore, the law was carefully drawn in order to avoid running afoul of the constitutional provision reserving police powers to the several states. In line with this restriction, the Act was presented as a revenue measure, taxing unlicensed purveyors of opiate drugs at an exorbitant rate while permitting licensed purveyors (primarily physicians, dentists, veterinarians, and pharmacists) to pay a nominal tax. Though it was justified constitutionally as a revenue measure, the Harrison Act was in fact a police measure and was so interpreted by those to whom its enforcement was entrusted. One consequence of the passage of the Act was the establishment, in the Treasury Department, of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics in

1930.

The same values that led to the banning of the use of alcohol and opiates could, of course, be applied to the case of marihuana and it seems logical that this should have been done. Yet what little I have been told, by people familiar with the period, about the use of marihuana in the late 'twenties and early 'thirties leads me to believe that there was relatively lax enforcement of the existing local laws. This, after all, was the era of Prohibition and the police had more pressing matters to attend to. Neither the public nor law enforcement officers, apparently, considered the use of marihuana a serious problem. When they noticed it at all, they probably dismissed it as not warranting major attempts at enforcement. One index of how feebly the laws were enforced is that the price of marihuana is said to have been very much lower prior to the passage of Federal legislation. This indicates that there was little danger in selling it and that enforcement was not seriously undertaken.

Even the Treasury Department, in its report on the year 1931, minimized the importance of the problem:

A great deal of public interest has been aroused by newspaper articles appearing from time to time on the evils of the abuse of marihuana, or Indian hemp, and more attention has been focused on specific cases reported of the abuse of the drug than would otherwise have been the case. This publicity tends to magnify the extent of the evil and lends color to an inference that there is an alarming spread of the improper use of the drug, whereas the actual increase in such use may not have been inordinately large.9

The Treasury Department's Bureau of Narcotics furnished most of the enterprise that produced the Marihuana Tax Act. While it is, of course, difficult to know what the motives of Bureau officials were, we need assume no more than that they perceived an area of wrongdoing that properly belonged in their jurisdiction and moved to put it there. The personal interest they satisfied in pressing for marihuana legislation was one common to many officials: the interest in successfully accomplishing the task one has been assigned and in acquiring the best tools with which to accomplish it. The Bureau's efforts took two forms: cooperating in the development of state legislation affecting the use of marihuana, and providing facts and figures for journalistic accounts of the problem. These are two important modes of action available to all entrepreneurs seeking the adoption of rules: they can enlist the support of other interested organizations and develop, through the use of the press and other communications media, a favorable public attitude toward the proposed rule. If the efforts are successful, the public becomes aware of a definite problem and the appropriate organizations act in concert to produce the desired rule.

The Federal Bureau of Narcotics cooperated actively with the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws in developing uniform laws on narcotics, stressing among other matters the need to control marihuana use.1° In 1932, the Conference approved a draft law. The Bureau commented:

The present constitutional limitations would seem to require control measures directed against the intrastate traffic in Indian hemp to be adopted by the several State governments rather than by the Federal Government, and the policy has been to urge the State authorities generally to provide the necessary legislation, with supporting enforcement activity, to prohibit the traffic except for bona fide medical purposes. The proposed uniform State narcotic law . . . with optional text applying to the restriction of traffic in Indian hemp, has been recommended as an adequate law to accomplish the desired purposes.11

In its report for the year 1936, the Bureau urged its partners in this cooperative effort to exert themselves more strongly and hinted that Federal intervention might perhaps be necessary:

In the absence of additional Federal legislation the Bureau of Narcotics can therefore carry on no war of its own against this traffic . . . the drug has come into wide and increasing abuse in many states, and the Bureau of Narcotics has therefore been endeavoring to impress upon the various States the urgent need for vigorous enforcement of local cannabis [marihuana] laws.12

The second prong of the Bureau's attack on the marihuana problem consisted of an effort to arouse the public to the danger confronting it by means of "an educational campaign describing the drug, its identification, and evil effects." 13 Ap-

parently hoping that public interest might spur the States and cities to greater efforts, the Bureau said:

In the absence of Federal legislation on the subject, the States and cities should rightfully assume the responsibility of providing vigorous measures for the extinction of this lethal weed, and it is therefore hoped that all public-spirited citizens will earnestly enlist in the movement urged by the Treasury Department to adjure intensified enforcement of marihuana laws."

The Bureau did not confine itself to exhortation in departmental reports. Its methods in pursuing desired legislation are described in a passage dealing with the campaign for a uniform state narcotic law:

Articles were prepared in the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, at the request of a number of organizations dealing with this general subject [uniform state laws] for publication by such organizations in magazines and newspapers. An intelligent and sympathetic public interest, helpful to the administration of the narcotic laws, has been aroused and maintained.15

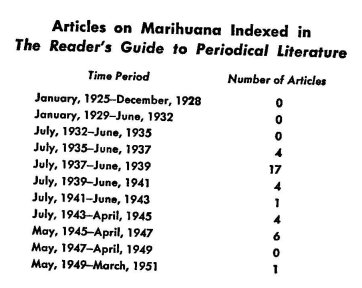

As the campaign for Federal legislation against marihuana drew to a successful close, the Bureau's efforts to communicate its sense of the urgency of the problem to the public bore plentiful fruit. The number of articles about marihuana which appeared in popular magazines indicated by the number indexed in the Reader's Guide, reached a record high. Seventeen articles appeared in a two-year period, many more than in any similar period before or after.

Of the seventeen, ten either explicitly acknowledged the help of the Bureau in furnishing facts and figures or gave implicit evidence of having received help by using facts and figures that had appeared earlier, either in Bureau publications or in testimony before the Congress on the Marihuana Tax Act. (We will consider the Congressional hearings on the bill in a moment.)

One clear indication of Bureau influence in the preparation of journalistic articles can be found in the recurrence of certain atrocity stories first reported by the Bureau. For instance, in an article published in the American Magazine, the Commissioner of Narcotics himself related the following incident:

An entire family was murdered by a youthful [marihuana] addict in Florida. When officers arrived at the home they found the youth staggering about in a human slaughterhouse. With an ax he had killed his father, mother, two brothers, and a sister. He seemed to be in a daze. . . . He had no recollection of having committed the multiple crime. The officers knew him ordinarily as a sane, rather quiet young man; now he was pitifully crazed. They sought the reason. The boy said he had been in the habit of smoking something which youthful friends called "muggles," a childish name for marihuana."

Five of the seventeen articles printed during the period repeated this story, and thus showed the influence of the Bureau.

The articles designed to arouse the public to the dangers of marihuana identified use of the drug as a violation of the value of self-control and the prohibition on search for "illicit pleasure," thus legitimizing the drive against marihuana in the eyes of the public. These, of course, were the same values that had been appealed to in the course of the quest for legislation prohibiting use of alcohol and opiates for illicit purposes.

The Federal Bureau of Narcotics, then, provided most of the enterprise which produced public awareness of the problem and coordinated action by other enforcement organizations. Armed with the results of their enterprise, representatives of the Treasury Department went to Congress with a draft of the Marihuana Tax Act and requested its passage. The hearings of the House Committee on Ways and Means, which considered the bill for five days during April and May of 1937, furnish a clear case of the operation of enterprise and of the way it must accommodate other interests.

The Assistant General Counsel of the Treasury Department introduced the bill to the Congressmen with these words: "The leading newspapers of the United States have recognized the seriousness of this problem and many of them have advocated Federal legislation to control the traffic in marihuana." 17 After explaining the constitutional basis of the bill—like the Harrison Act, it was framed as a revenue measure—he reassured them about its possible effects on legitimate businesses:

The form of the bill is such, however, as not to interfere materially with any industrial, medical, or scientific uses which the plant may have. Since hemp fiber and articles manufactured therefrom [twine and light cordage] are obtained from the harmless mature stalk of the plant, all such products have been completely eliminated from the purview of the bill by defining the term "marihuana" in the bill so as to exclude from its provisions the mature stalk and its compounds or manufacturers. There are also some dealings in marihuana seeds for planting purposes and for use in the manufacture of oil which is ultimately employed by the paint and varnish industry. As the seeds, unlike the mature stalk, contain the drug, the same complete exemption could not be applied in this instance.18

He further assured them that the medical profession rarely used the drug, so that its prohibition would work no hardship on them or on the pharmaceutical industry.

The committee members were ready to do what was necessary and, in fact, queried the Commissioner of Narcotics as to why this legislation had been proposed only now. He explained:

Ten years ago we only heard about it throughout the Southwest. It is only in the last few years that it has become a national menace. . . . We have been urging uniform State legislation on the several States, and it was only last month that the last State legislature adopted such legislation."19

The commissioner reported that many crimes were committed under the influence of marihuana, and gave examples, including the story of the Florida mass-murderer. He pointed out that the present low prices of the drug made it doubly dangerous, because it was available to anyone who had a dime to spare.

Manufacturers of hempseed oil voiced certain objections to the language of the bill, which was quickly changed to meet their specifications. But a more serious objection came from the birdseed industry, which at that time used some four million pounds of hempseed a year. Its representative apologized to the Congressmen for appearing at the last minute, stating that he and his colleagues had not realized until just then that the marihuana plant referred to in the bill was the same plant from which they got an important ingredient of their product. Government witnesses had insisted that the seeds of the plant required prohibition, as well as the flowering tops smokers usually used, because they contained a small amount of the active principle of the drug and might possibly be used for smoking. The birdseed manufacturers contended that inclusion of seed under the provisions of the bill would damage their business.

To justify his request for exemption, the manufacturers' representative pointed to the beneficial effect of hempseed on pigeons:

[It] is a necessary ingredient in pigeon feed because it contains an oil substance that is a valuable ingredient of pigeon feed, and we have not been able to find any seed that will take its place. If you substitute anything for the hemp, it has a tendency to change the character of the squabs produced."20

Congressman Robert L. Doughton of North Carolina inquired: "Does that seed have the same effect on pigeons as the drug has on human beings?" The manufacturers' representative said: "I have never noticed it. It has a tendency to bring back the feathers and improve the birds." 21

Faced with serious opposition, the Government modified its stern insistence on the seed provision, noting that sterilization of the seeds might render them harmless: "It seems to us that the burden of proof is on the Government there, when we might injure a legitimate industry. /) 22

Once these difficulties had been ironed out, the bill had easy sailing. Marihuana smokers, powerless, unorganized, and lacking publicly legitimate grounds for attack, sent no representatives to the hearings and their point of view found no place in the record. Unopposed, the bill passed both the House and Senate the following July. The enterprise of the Bureau had produced a new rule, whose subsequent enforcement would help create a new class of outsiders—marihuana users.

I have given an extended illustration from the field of Federal legislation. But the basic parameters of this case should be equally applicable not only to legislation in general, but to the development of rules of a more informal kind. Wherever rules are created and applied, we should be alive to the possible presence of an enterprising individual or group. Their activities can properly be called moral enterprise, for what they are enterprising about is the creation of a new fragment of the moral constitution of society, its code of right and wrong.

Wherever rules are created and applied we should expect to find people attempting to enlist the support of coordinate groups and using the available media of communication to develop a favorable climate of opinion. Where they do not develop such support, we may expect to find their enterprise unsuccessf u1.23

And, wherever rules are created and applied, we expect that the processes of enforcement will be shaped by the complexity of the organization, resting on a basis of shared understandings in simpler groups and resulting from political maneuvering and bargaining in complex structures.

1. Kurt H. Wolff, translator and editor, The Sociology of Georg Simnel (New York: The Free Press of Glencoe, 1950), pp. 415-416.

2. Melville Dalton, Men Who Manage: Fusions of Feeling and Theory in Administration (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1959), pp. 199-205.

3. Ibid., pp. 194-215.

4. Donald Roy, "Quota Restriction and Goldbricking in a Machine Shop," American Journal of Sociology, LVII (March, 1952), 427-442.

5. Donald Roy, "Efficiency and 'The Fix': Informal Intergroup Relations in a Piecework Machine Shop," American Journal of Sociology, LX (November, 1954), 255-266.

6. Talcott Parsons, The Social System (New York: The Free Press of Glencoe, 1951), p. 12.

7. For a natural history approach to social problems, see Richard C. Fuller and R. R. Meyers, "Some Aspects of a Theory of Social Problems," American Sociological Review, 6 (February, 1941), 24-32.

8. See John Krout, The Origins of Prohibition (New York: Columbia University Press, 1928); Charles Terry and Mildred Pellens, The Opium Problem (New York: The Committee on Drug Addiction with the Bureau of Social Hygiene, Inc., 1928); and Drug Addiction: Crime or Disease? Interim and Final Reports of the Joint Committee of the American Bar Association and the American Medical Association on Narcotic Drugs (Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1961).

9. U.S. Treasury Department, Traffic in Opium and Other Dangerous Drugs for the Year ended December 31, 1931 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1932), p. 51.

10. Ibid., pp. 16-17.

11. Bureau of Narcotics, U.S. Treasury Department, Traffic in Opium and Other Dangerous Drugs for the Year ended December 31, 1932 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1933), p. 13.

12. Bureau of Narcotics, U.S. Treasury Department, Traffic in Opium and Other Dangerous Drugs for the Year ended December 31, 1936 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1937), p. 59.

13. Ibid.

14. Bureau of Narcotics, U.S. Treasury Department, Traffic in Opium and Other Dangerous Drugs for the Year ended December 31, 1935 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1936), p. 30.

15. Bureau of Narcotics, U.S. Treasury Department, Traffic in Opium and Other Dangerous Drugs for the Year ended December 31, 1933 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1934), p. 61.

16. H. J. Anslinger, with Courtney Ryley Cooper, "Marihuana: Assassin of Youth," American Magazine, CXXIV (July, 1937), 19, 150.

17. Taxation of Marihuana (Hearings before the Committee on Ways and Means of the House of Representatives, 75th Congress, 1st Session, on H.R. 6385, April 27-30 and May 4, 1937), p. 7.

18. Ibid., p. 8.

19. Ibid., p. 20.

20. Ibid., pp. 73-74.

21. Ibid.

22. Ibid., p. 85.

23. Gouldner has described a relevant case in industry, where a new manager's attempt to enforce rules that had not been enforced for a long time (and thus, in effect, create new rules) had as its immediate consequence a disruptive wildcat strike; he had not built support through the manipulation of other groups in the factory and the development of a favorable climate of opinion. See Alvin W. Gonldner, Wildcat Strike (Yellow Springs, Ohio: Antioch Press, 1954).

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|