2 Kinds of Deviance

| Books - Outsiders |

Drug Abuse

2 Kinds of Deviance

A SEQUENTIAL MODEL

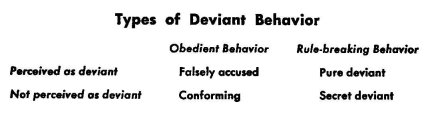

IT is not my purpose here to argue that only acts which are regarded as deviant by others are "really" deviant. But it must be recognized that this is an important dimension, one which needs to be taken into account in any analysis of deviant behavior. By combining this dimension with another—whether or not an act conforms to a particular rule—we can construct the following set of categories for the discrimination of different kinds of deviance.

Two of these types require very little explanation. Conforming behavior is simply that which obeys the rule and which others perceive as obeying the rule. At the other extreme, the pure deviant type of behavior is that which both disobeys the rule and is perceived as doing so.*

The two other possibilities are of more interest. The falsely accused situation is what criminals often refer to as a "bum rap." The person is seen by others as having committed an improper action, although in fact he has not done so. False accusations undoubtedly occur even in courts of law, where the person is protected by rules of due process and evidence. They probably occur much more frequently in nonlegal settings where procedural safeguards are not available.

An even more interesting kind of case is found at the other extreme of secret deviance. Here an improper act is committed, yet no one notices it or reacts to it as a violation of the rules. As in the case of false accusation, no one really knows how much of this phenomenon exists, but I am convinced the amount is very sizable, much more so than we are apt to think. One brief observation convinces me this is the case. Most people probably think of fetishism (and sado-masochistic fetishism in particular) as a rare and exotic perversion. I had occasion several years ago, however, to examine the catalog of a dealer in pornographic pictures designed exclusively for devotees of this specialty. The catalog contained no pictures of nudes, no pictures of any version of the sex act. Instead, it contained page after page of pictures of girls in straitjackets, girls wearing boots with six-inch heels, girls holding whips, girls in handcuffs, and girls spanking one another. Each page served as a sample of as many as 120 pictures stocked by the dealer. A quick calculation revealed that the catalog advertised for immediate sale somewhere between fifteen and twenty thousand different photographs. The catalog itself was expensively printed and this fact, taken together with the number of photographs for sale, indicated clearly that the dealer did a land-office business and had a very sizable clientele. Yet one does not run across sado-masochistic fetishists every day. Obviously, they are able to keep the fact of their perversion secret ("All orders mailed in a plain envelope") •1

Similar observations have been made by students of homosexuality,' who note that many homosexuals are able to keep their deviance secret from their nondeviant associates. And many users of narcotic drugs, as we shall see later, are able to hide their addiction from the nonusers they associate with.

The four theoretical types of deviance, which we created by cross-classifying kinds of behavior and the responses they evoke, distinguish between phenomena that differ in important respects but are ordinarily considered to be similar. If we ignore the differences we may commit the fallacy of trying to explain several different kinds of things in the same way, and ignore the possibility that they may require different explanations. A boy who is innocently hanging around the fringes of a delinquent group may be arrested with them some night on suspicion. He will show up in the official statistics as a delinquent just as surely as those who have actually been involved in wrongdoing, and social scientists who try to develop theories to explain delinquency will attempt to account for his presence in the official records in the same way they try to account for the presence of the others.2 But the cases are different; the same explanation will not do for both.

Simultaneous and

Sequential Models of Deviance

The discrimination of types of deviance may help us understand how deviant behavior originates. It will do so by enabling us to develop a sequential model of deviance, a model that allows for change through time. But before discussing the model itself, let us consider the differences between a sequential model and a simultaneous model in the development of individual behavior.

First of all, let us note that almost all research in deviance deals with the kind of question that arises from viewing it as pathological. That is, research attempts to discover the "etiology" of the "disease." It attempts to discover the causes of unwanted behavior.

This search is typically undertaken with the tools of multivariate analysis. The techniques and tools used in social research invariably contain a theoretical as well as a methodological commitment, and such is the case here. Multivariate analysis assumes (even though its users may in fact know better) that all the factors which operate to produce the phenomenon under study operate simultaneously. It seeks to discover which variable or what combination of variables will best "predict" the behavior one is studying. Thus, a study of juvenile delinquency may attempt to discover whether it is the intelligence quotient, the area in which a child lives, whether or not he comes from a broken home, or a combination of these factors that accounts for his being delinquent.

But, in fact, all causes do not operate at the same time, and we need a model which takes into account the fact that patterns of behavior develop in orderly sequence. In accounting for an individual's use of marihuana, as we shall see later, we must deal with a sequence of steps, of changes in the individual's behavior and perspectives, in order to understand the phenomenon. Each step requires explanation, and what may operate as a cause at one step in the sequence may be of negligible importance at another step. We need, for example, one kind of explanation of how a person comes to be in a situation where marihuana is easily available to him, and another kind of explanation of why, given the fact of its availability, he is willing to experiment with it in the first place. And we need still another explanation of why, having experimenttd with it, he continues to use it. In a sense, each explanation constitutes a necessary cause of the behavior. That is, no one could become a confirmed marihuana user without going through each step. He must have the drug available, experiment with it, and continue to use it. The explanation of each step is thus part of the explanation of the resulting behavior.

Yet the variables which account for each step may not, taken separately, distinguish between users and nonusers. The variable which disposes a person to take a particular step may not operate because he has not yet reached the stage in the process where it is possible to take that step. Let us suppose, for example, that one of the steps in the formation of an habitual pattern of drug use—willingness to experiment with use of the drug—is really the result of a variable of personality or personal orientation such as alienation from conventional norms. The variable of personal alienation, however, will only produce drug use in people who are in a position to experiment because they participate in groups in which drugs are available; alienated people who do not have drugs available to them cannot begin experimentation and thus cannot become users, no matter how alienated they are. Thus alienation might be a necessary cause of drug use, but distinguish between users and nonusers only at a particular stage in the process.

A useful conception in developing sequential models of various kinds of deviant behavior is that of career.3 Originally developed in studies of occupations, the concept refers to the sequence of movements from one position to another in an occupational system made by any individual who works in that system. Furthermore, it includes the notion of "career contingency," those factors on which mobility from one position to another depends. Career contingencies include both objective facts of social structure and changes in the perspectives, motivations, and desires of the individual. Ordinarily, in the study of occupations, we use the concept to distinguish between those who have a "successful" career (in whatever terms success is defined within the occupation) and those who do not. It can also be used to distinguish several varieties of career outcomes, ignoring the question of "success."

The model can easily be transformed for use in the study of deviant careers. In so transforming it, we should not confine our interest to those who follow a career that leads them into ever-increasing deviance, to those who ultimately take on an extremely deviant identity and way of life. We should also consider those who have a more fleeting contact with deviance, whose careers lead them away from it into conventional ways of life. Thus, for example, studies of delinquents who fail to become adult criminals might teach us even more than studies of delinquents who progress in crime.

In the rest of this chapter I will consider the possibilities inherent in the career approach to deviance. Then I will turn to a study of a particular kind of deviance: the use of marihuana.

Deviant Careers

The first step in most deviant careers is the commission of a nonconforming act, an act that breaks some particular set of rules. How are we to account for the first step?

People usually think of deviant acts as motivated. They believe that the person who commits a deviant act, even for the first time (and perhaps especially for the first time), does so purposely. His purpose may or may not be entirely conscious, but there is a motive force behind it. We shall turn to the consideration of cases of intentional nonconformity in a moment, but first I must point out that many nonconforming acts are committed by people who have no intention of doing so; these clearly require a different explanation.

Unintended acts of deviance can probably be accounted for relatively simply. They imply an ignorance of the existence of the rule, or of the fact that it was applicable in this case, or to this particular person. But it is necessary to account for the lack of awareness. How does it happen that the person does not know his act is improper? Persons deeply involved in a particular subculture (such as a religious or ethnic subculture) may simply be unaware that everyone does not act "that way" and thereby commit an impropriety. There may, in fact, be structured areas of ignorance of particular rules. Mary Haas has pointed out the interesting case of interlingual word taboos.4 Words which are perfectly proper in one language have a "dirty" meaning in another. So the person, innocently using a word common in his own language, finds that he has shocked and horrified his listeners who come from a different culture.

In analyzing cases of intended nonconformity, people usually ask about motivation: why does the person want to do the deviant thing he does? The question assumes that the basic difference between deviants and those who conform lies in the character of their motivation. Many theories have been propounded to explain why some people have deviant motivations and others do not. Psychological theories find the cause of deviant motivations and acts in the individual's early experiences, which produce unconscious needs that must be satisfied if the individual is to maintain his equilibrium. Sociological theories look for socially structured sources of "strain" in the society, social positions which have conflicting demands placed upon them such that the individual seeks an illegitimate way of solving the problems his position presents him with. (Merton's famous theory of anomie fits into this category.) 5

But the assumption on which these approaches are based may be entirely false. There is no reason to assume that only those who finally commit a deviant act actually have the impulse to do so. It is much more likely that most people experience deviant impulses frequently. At least in fantasy, people are much more deviant than they appear. Instead of asking why deviants want to do things that are disapproved of, we might better ask why conventional people do not follow through on the deviant impulses they have.

Something of an answer to this question may be found in the process of commitment through which the "normal" person becomes progressively involved in conventional institutions and behavior. In speaking of comrnitment,6 I refer to the process through which several kinds of interests become bound up with carrying out certain lines of behavior to which they seem formally extraneous. What happens is that the individual, as a consequence of actions he has taken in the past or the operation of various institutional routines, finds he must adhere to certain lines of behavior, because many other activities than the one he is immediately engaged in will be adversely affected if he does not. The middle-class youth must not quit school, because his occupational future depends on receiving a certain amount of schooling. The conventional person must not indulge his interests in narcotics, for example, because much more than the pursuit of immediate pleasure is involved; his job, his family, and his reputation in his neighborhood may seem to him to depend on his continuing to avoid temptation.

In fact, the normal development of people in our society (and probably in any society) can be seen as a series of progressively increasing commitments to conventional norms and institutions. The "normal" person, when he discovers a deviant impulse in himself, is able to check that impulse by thinking of the manifold consequences acting on it would produce for him. He has staked too much on continuing to be normal to allow himself to be swayed by unconventional impulses.

This suggests that in looking at cases of intended nonconformity we must ask how the person manages to avoid the impact of conventional commitments. He may do so in one of two ways. First of all, in the course of growing up the person may somehow have avoided entangling alliances with conventional society. He may, thus, be free to follow his impulses. The person who does not have a reputation to maintain or a conventional job he must keep may follow his impulses. He has nothing staked on continuing to appear conventional.

However, most people remain sensitive to conventional codes of conduct and must deal with their sensitivities in order to engage in a deviant act for the first time. Sykes and Mat2a have suggested that delinquents actually feel strong impulses to be law-abiding, and deal with them by techniques of neutralization: "justifications for deviance that are seen as valid by the delinquent but not by the legal system or society at large." They distinguish a number of techniques for neutralizing the force of law-abiding values.

In so far as the delinquent can define himself as lacking responsibility for his deviant actions, the disapproval of self or others is sharply reduced in effectiveness as a restraining influence. . . . The delinquent approaches a "billiard ball" conception of himself in which he sees himself as helplessly propelled into new situations. . . . By learning to view himself as more acted upon than acting, the delinquent prepares the way for deviance from the dominant normative system without the necessity of a frontal assault on the norms themselves. . . .

A second major technique of neutralization centers on the injury or harm involved in the delinquent act. . . . For the delinquent . . . wrongfulness may turn on the question of whether or not anyone has clearly been hurt by his deviance, and this matter is open to a variety of interpretations. . . . Auto theft may be viewed as "borrowing," and gang fighting may be seen as a private quarrel, an agreed upon duel between two willing parties, and thus of no concern to the community at large. . . .

The moral indignation of self and others may be neutralized by an insistence that the injury is not wrong in light of the circurnstances. The injury, it may be claimed, is not really an injury; rather, it is a form of rightful retaliation or punishment. • . . Assaults on homosexuals or suspected homosexuals, attacks on members of minority groups who are said to have gotten "out of place," vandalism as revenge on an unfair teacher or school official, thefts from a "crooked" store owner—all may be hurts inflicted on a transgressor, in the eyes of the delinquent. . . .

A fourth technique of neutralization would appear to involve a condemnation of the condemners. . . . His condemners, he may claim, are hypocrites, deviants in disguise, or impelled by personal spite. . . . By attacking others, the wrongfulness of his own behavior is more easily repressed or lost to view. . . .

Internal and external social controls may be neutralized by sacrificing the demands of the larger society for the demands of the smaller social groups to which the delinquent belongs such as the sibling pair, the gang, or the friendship clique. . . . The most important point is that deviation from certain norms may occur not because the norms are rejected but because other norms, held to be more pressing or involving a higher loyalty, are accorded precedence.7

In some cases a nonconforming act may appear necessary or expedient to a person otherwise law-abiding. Undertaken in pursuit of legitimate interests, the deviant act becomes, if not quite proper, at least not quite improper. In a novel dealing with a young Italian-American doctor we find a good example.8 The young man, just out of medical school, would like to have a practice that is not built on the fact of his being Italian. But, being Italian, he finds it difficult to gain acceptance from the Yankee practitioners of his community. One day he is suddenly asked by one of the biggest surgeons to handle a case for him and thinks that he is finally being admitted to the referral system of the better doctors in town. But when the patient arrives at his office, he finds the case is an illegal abortion. Mistakenly seeing the referral as the first step in a regular relationship with the surgeon, he performs the operation. This act, although improper, is thought necessary to building his career.

But we are not so much interested in the person who commits a deviant act once as in the person who sustains a pattern of deviance over a long period of time, who makes of deviance a way of life, who organizes his identity around a pattern of deviant behavior. It is not the casual experimenters with homosexuality (who turned up in such surprisingly large numbers in the Kinsey Report) that we want to find out about, but the man who follows a pattern of homosexual activity throughout his adult life.

One of the mechanisms that lead from casual experimentation to a more sustained pattern of deviant activity is the development of deviant motives and interests. We shall examine this process in detail later, when we consider the career of the marihuana user. Here it is sufficient to say that many kinds of deviant activity spring from motives which are socially learned. Before engaging in the activity on a more or less regular basis, the person has no notion of the pleasures to be derived from it; he learns these in the course of interaction with more experienced deviants. He learns to be aware of new kinds of experiences and to think of them as pleasurable. What may well have been a random impulse to try something new becomes a settled taste for something already known and experienced. The vocabularies in which deviant motivations are phrased reveal that their users acquire them in interaction with other deviants. The individual learns, in short, to participate in a subculture organized around the particular deviant activity.

Deviant motivations have a social character even when most of the activity is carried on in a private, secret, and solitary fashion. In such cases, various media of communication may take the place of face-to-face interaction in inducting the individual into the culture. The pornographic pictures I mentioned earlier were described to prospective buyers in a stylized language. Ordinary words were used in a technical shorthand designed to whet specific tastes. The word "bondage," for instance, was used repeatedly to refer to pictures of women restrained in handcuffs or straitjackets. One does not acquire a taste for "bondage photos" without having learned what they are and how they may be enjoyed.

One of the most crucial steps in the process of building a stable pattern of deviant behavior is likely to be the experience of being caught and publicly labeled as a deviant. Whether a person takes this step or not depends not so much on what he does as on what other people do, on whether or not they enforce the rule he has violated. Although I will consider the circumstances under which enforcement takes place in some detail later, two notes are in order here. First of all, even though no one else discovers the nonconformity or enforces the rules against it, the individual who has committed the impropriety may himself act as enforcer. He may brand himself as deviant because of what he has done and punish himself in one way or another for his behavior. This is not always or necessarily the case, but may occur. Second, there may be cases like those described by psychoanalysts in which the individual really wants to get caught and perpetrates his deviant act in such a way that it is almost sure he will be.

In any case, being caught and branded as deviant has important consequences for one's further social participation and self-image. The most important consequence is a drastic change in the individual's public identity. Committing the improper act and being publicly caught at it place him in a new status. He has been revealed as a different kind of person from the kind he was supposed to be. He is labeled a "fairy," "dope fiend," "nut" or "lunatic," and treated accordingly.

In analyzing the consequences of assuming a deviant identity let us make use of Hughes' distinction between master and auxiliary status traits.° Hughes notes that most statuses have one key trait which serves to distinguish those who belong from those who do not. Thus the doctor, whatever else he may be, is a person who has a certificate stating that he has fulfilled certain requirements and is licensed to practice medicine; this is the master trait. As Hughes points out, in our society a doctor is also informally expected to have a number of auxiliary traits: most people expect him to be upper middle class, white, male, and Protestant. When he is not there is a sense that he has in some way failed to fill the bill. Similarly, though skin color is the master status trait determining who is Negro and who is white, Negroes are informally expected to have certain status traits and not to have others; people are surprised and find it anomalous if a Negro turns out to be a doctor or a college professor. People often have the master status trait but lack some of the auxiliary, informally expected characteristics; for example, one may be a doctor but be female or Negro.

Hughes deals with this phenomenon in regard to statuses that are well thought of, desired and desirable (noting that one may have the formal qualifications for entry into a status but be denied full entry because of lack of the proper auxiliary traits), but the same process occurs in the case of deviant statuses. Possession of one deviant trait may have a generalized symbolic value, so that people automatically assume that its bearer possesses other undesirable traits allegedly associated with it.

To be labeled a criminal one need only commit a single criminal offense, and this is all the term formally refers to. Yet the word carries a number of connotations specifying auxiliary traits characteristic of anyone bearing the label. A. man who has been convicted of housebreaking and thereby labeled criminal is presumed to be a person likely to break into other houses; the police, in rounding up known offenders for investigation after a crime has been committed, operate on this premise. Further, he is considered likely to commit other kinds of crimes as well, because he has shown himself to be a person without "respect for the law." Thus, apprehension for one deviant act exposes a person to the likelihood that he will be regarded as deviant or undesirable in other respects.

There is one other element in Hughes' analysis we can borrow with profit: the distinction between master and subordinate statuses.1° Some statuses, in our society as in others, override all other statuses and have a certain priority. Race is one of these. Membership in the Negro race, as socially defined, will override most other status considerations in most other situations; the fact that one is a physician or middle-class or female will not protect one from being treated as a Negro first and any of these other things second. The status of deviant (depending on the kind of deviance) is this kind of master status. One receives the status as a result of breaking a rule, and the identification proves to be more important than most others. One will be identified as a deviant first, before other identifications are made. The question is raised:

"What kind of person would break such an important rule?" And the answer is given: "One who is different from the rest of us, who cannot or will not act as a moral human being and therefore might break other important rules." The deviant identification becomes the controlling one.

Treating a person as though he were generally rather than specifically deviant produces a self-fulfilling prophecy. It sets in motion several mechanisms which conspire to shape the person in the image people have of him." In the first place, one tends to be cut off, after being identified as deviant, from participation in more conventional groups, even though the specific consequences of the particular deviant activity might never of themselves have caused the isolation had there not also been the public knowledge and reaction to it. For example, being a homosexual may not affect one's ability to do office work, but to be known as a homosexual in an office may make it impossible to continue working there. Similarly, though the effects of opiate drugs may not impair one's working ability, to be known as an addict will probably lead to losing one's job. In such cases, the individual finds it difficult to conform to other rules which he had no intention or desire to break, and perforce finds himself deviant in these areas as well. The homosexual who is deprived of a "respectable" job by the discovery of his deviance may drift into unconventional, marginal occupations where it does not make so much difference. The drug addict finds himself forced into other illegitimate kinds of activity, such as robbery and theft, by the refusal of respectable employers to have him around.

When the deviant is caught, he is treated in accordance with the popular diagnosis of why he is that way, and the treatment itself may likewise produce increasing deviance.

The drug addict, popularly considered to be a weak-willed individual who cannot forego the indecent pleasures afforded him by opiates, is treated repressively. He is forbidden to use drugs. Since he cannot get drugs legally, he must get them illegally. This forces the market underground and pushes the price of drugs up far beyond the current legitimate market price into a bracket that few can afford on an ordinary salary. Hence the treatment of the addict's deviance places him in a position where it will probably be necessary to resort to deceit and crime in order to support his habit.12 The behavior is a consequence of the public reaction to the deviance rather than a consequence of the inherent qualities of the deviant act.

Put more generally, the point is that the treatment of deviants denies them the ordinary means of carrying on the routines of everyday life open to most people. Because of this denial, the deviant must of necessity develop illegitimate routines. The influence of public reaction may be direct, as in the instances considered above, or indirect, a consequence of the integrated character of the society in which the deviant lives.

Societies are integrated in the sense that social arrangements in one sphere of activity mesh with other activities in other spheres in particular ways and depend on the existence of these other arrangements. Certain kinds of work lives presuppose a certain kind of family life, as we shall see when we consider the case of the dance musician.

Many varieties of deviance create difficulties by failing to mesh with expectations in other areas of life. Homosexuality is a case in point. Homosexuals have difficulty in any area of social activity in which the assumption of normal sexual interests and propensities for marriage is made without question.

In stable work organizations such as large business or industrial organizations there are often points at which the man who would be successful should marry; not to do so will make it difficult for him to do the things that are necessary for success in the organization and will thus thwart his ambitions. The necessity of marrying often creates difficult enough problems for the normal male, and places the homosexual in an almost impossible position. Similarly, in some male work groups where heterosexual prowess is required to retain esteem in the group, the homosexual has obvious difficulties. Failure to meet the expectations of others may force the individual to attempt deviant ways of achieving results automatic for the normal person.

Obviously, everyone caught in one deviant act and labeled a deviant does not move inevitably toward greater deviance in the way the preceding remarks might suggest. The prophecies do not always confirm themselves, the mechanisms do not always work. What factors tend to slow down or halt the movement toward increasing deviance? Under what circumstances do they come into play?

One suggestion as to how the person may be immunized against increasing deviance is found in a recent study of juvenile delinquents who "hustle" homosexuals.13 These boys act as homosexual prostitutes to confirmed adult homosexuals. Yet they do not themselves become homosexual. Several things account for their failure to continue this kind of sexual deviancy. First, they are protected from police action by the fact that they are minors. If they are apprehended in a homosexual act, they will be treated as exploited children, although in fact they are the exploiters; the law makes the adult guilty. Second, they look on the homosexual acts they engage in simply as a means of making money that is safer and quicker than robbery or similar activities. Third, the standards of their peer group, while permitting homosexual prostitution, allow only one kind of activity, and forbid them to get any special pleasure out of it or to permit any expressions of endearment from the adult with whom they have relations. Infractions of these rules, or other deviations from normal heterosexual activity, are severely punished by the boy's fellows.

Apprehension may not lead to increasing deviance if the situation in which the individual is apprehended for the first time occurs at a point where he can still choose between alternate lines of action. Faced, for the first time, with the possible ultimate and drastic consequences of what he is doing, he may decide that he does not want to take the deviant road, and turn back. If he makes the right choice, he will be welcomed back into the conventional community; but if he makes the wrong move, he will be rejected and start a cycle of increasing deviance.

Ray has shown, in the case of drug addicts, how difficult it can be to reverse a deviant cycle." He points out that drug addicts frequently attempt to cure themselves and that the motivation underlying their attempts is an effort to show non-addicts whose opinions they respect that they are really not as bad as they are thought to be. On breaking their habit successfully, they find, to their dismay, that people still treat them as though they were addicts (on the premise, apparently, of "once a junkie, always a junkie").

A final step in the career of a deviant is movement into an organized deviant group. When a person makes a definite move into an organized group—or when he realizes and accepts the fact that he has already done so—it has a powerful impact on his conception of himself. A drug addict once told me that the moment she felt she was really "hooked" was when she realized she no longer had any friends who were not drug addicts.

Members of organized deviant groups of course have one thing in common: their deviance. It gives them a sense of common fate, of being in the same boat. From a sense of common fate, from having to face the same problems, grows a deviant subculture: a set of perspectives and understandings about what the world is like and how to deal with it, and a set of routine activities based on those perspectives. Membership in such a group solidifies a deviant identity.

Moving into an organized deviant group has several consequences for the career of the deviant. First of all, deviant groups tend, more than deviant individuals, to be pushed into rationalizing their position. At an extreme, they develop a very complicated historical, legal, and psychological justification for their deviant activity. The homosexual community is a good case. Magazines and books by homosexuals and for homosexuals include historical articles about famous homosexuals in history. They contain articles on the biology and physiology of sex, designed to show that homosexuality is a "normal" sexual response. They contain legal articles, pleading for civil liberties for homosexuals." Taken together, this material provides a working philosophy for the active homosexual, explaining to him why he is the way he is, that other people have also been that way, and why it is all right for him to be that way.

Most deviant groups have a self-justifying rationale (or "ideology"), although seldom is it as well worked out as that of the homosexual. While such rationales do operate, as pointed out earlier, to neutralize the conventional attitudes that deviants may still find in themselves toward their own behavior, they also perform another function. They furnish the individual with reasons that appear sound for continuing the line of activity he has begun. A person who quiets his own doubts by adopting the rationale moves into a more principled and consistent kind of deviance than was possible for him before adopting it.

The second thing that happens when one moves into a deviant group is that he learns how to carry on his deviant activity with a minimum of trouble. All the problems he faces in evading enforcement of the rule he is breaking have been faced before by others. Solutions have been worked out. Thus, the young thief meets older thieves who, more experienced than he is, explain to him how to get rid of stolen merchandise without running the risk of being caught. Every deviant group has a great stock of lore on such subjects and the new recruit learns it quickly.

Thus, the deviant who enters an organized and institutionalized deviant group is more likely than ever before to continue in his ways. He has learned, on the one hand, how to avoid trouble and, on the other hand, a rationale for continuing.

One further fact deserves mention. The rationales of deviant groups tend to contain a general repudiation of conventional moral rules, conventional institutions, and the entire conventional world. We will examine a deviant subculture later when we consider the case of the dance musician.

* It should be remembered that this classification must always be used from the perspective of a given set of rules; it does not take into account the complexities, already discussed, that appear when there is more than one set of rules available for use by the same people in defining the same act. Furthermore, the classification has reference to types of behavior rather than types of people, to acts rather than personalities. The same person's behavior can obviously be conforming in some activities, deviant in others.

1. See also the discussion in James Jackson Kilpatrick, The Smut Peddlers (New York: Doubleday and Co., 1960), pp. 1-77.

2. I have profited greatly from reading an unpublished paper by John Kitsuse on the use of official statistics in research on deviance.

3. See Everett C. Hughes, Men and Their Work (New York: The Free Press of Glencoe, 1958), pp. 56-67, 102-115, and 157-168; Oswald Hall, "The Stages of the Medical Career," American Journal of Sociology, LIII (March, 1948), 243-253; and Howard S. Becker and Anselrn L. Strauss, "Careers, Personality, and Adult Socialization," American Journal of Sociology, LXII (November, 1956), 253-263.

4. Mary R. Haas, "Interlingual Word Taboos," American Anthropologist, 53 (July-September, 1951), 338-344.

5. Robert K. Merton, Social Theory and Social Structure (New York: The Free Press of Glencoe, 1957), pp. 131-194.

6. I have dealt with this concept at greater length in "Notes on the Concept of Commitment," American Journal of Sociology, LXVI (July, 1960), 32-40. See also Erving Goffman, Encounters: Two Studies in the Sociology of Interaction (Indianapolis: The Bobbs-Merrill Co., Inc., 1961), pp. 88-110; and Gregory P. Stone, "Clothing and Social Relations: A Study of Appearance in the Context of Community Life" (unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Sociology, University of Chicago, 1959).

7 Gresham M. Sykes and David Matza, "Techniques of Neutralization: A Theory of Delinquency," American Sociological Review, 22 (December, 1957), 667-669.

8. Guido D'Agostino, Olives on the Apple Tree (New York: Doubleday, Doran, 1940). I am grateful to Everett C. Hughes for calling this novel to my attention.

9. Everett C. Hughes, "Dilemmas and Contradictions of Status," American Journal of Sociology, L (March, 1945), 353-359.

10. Ibid.

11. See Marsh Ray, "The Cycle of Abstinence and Relapse Among Heroin Addicts," Social Problems, 9 (Fall, 1961), 132-140,

12. See Drug Addiction: Crime or Disease? Interim and Final Reports of the Joint Committee of the American Bar Association and the American Medical Association on Narcotic Drugs (Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1961).

13. Albert J. Reiss, Jr., "The Social Integration of Queers and Peers," Social Problems, 9 (Fall, 1961), 102-120.

14. Ray, op. cis.

15. One and The Mattachine Review are magazines of this type that I have seen.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|