5 A dynamic drugs policy

| Reports - NEW EMPHASIS IN DUTCH DRUGS POLICY |

Drug Abuse

5 A dynamic drugs policy

Beside the two particular issues of young people and coffee shops, the committee also considered drugs policy as a whole, since it was also asked to investigate prevention and care, the role of the Opium Act schedules, and measures to curb the production and trafficking of drugs. The committee does not intend to go into all these subjects individually in detail. Instead, it will examine them in relation to one another.

5.1 The search for consistency: a ‘dynamic drugs policy’

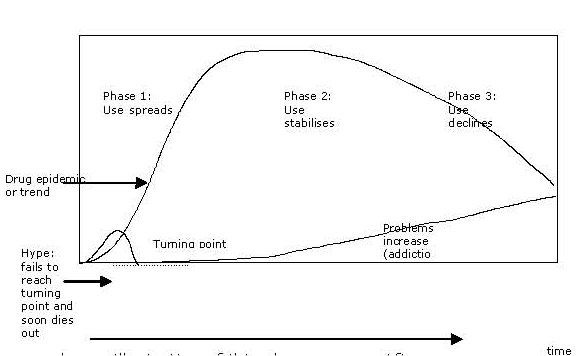

The desired consistency can be viewed in terms of the concept of a dynamic model of drug initiation, as described by Jonathan Caulkins of the RAND Corporation. The central idea – as shown in the figure below – is that drug use rises like a wave and then disappears again after some time. It thus resembles an epidemic, such as a flu epidemic. A substance becomes available, spreads among a limited group of people and, once it passes a turning point, spreads rapidly (by means of a selfreinforcing feedback mechanism, as people imitate each other, often assisted by a fall in the price as production and trade become established). After a certain saturation point, there follows a period in which the negative aspects of the substance – overdoses, addiction, crime –become more apparent. The popularity of the substance comes under pressure in part, perhaps, as a result of interventions. A negative feedback mechanism then sets in, and consumption falls, leaving a hard core of problem users.

Heroin provides a good illustration of this phenomenon. After use rose sharply, heroin gradually came to be seen as a ‘loser’s drug’. Nevertheless, a group consisting of tens of thousands of hardened drug addicts remained, who need longterm help. The situation with cannabis is not entirely clear, and differs from one country to another. In the US, for example, use peaked in the hippy era, after which it declined, only to experience a new surge in the 1990s, and then decline slightly again. Little is known about the first period in this country, but the pattern since the 1990s resembles that in the US.

According to this model, drug use is dynamic. Drugs policy must therefore also be dynamic, with measures that change over time according to the situation. The epidemic metaphor remains valid to a certain extent. Universal prevention measures are designed to provide information on the risks associated with a substance, and to prevent its use. During the first phase the key thing is to prevent use of the substance spreading, since such efforts have a double return in terms of fewer problems at a later stage. This requires a restrictive and, where necessary, repressive policy. Once use has become established, the emphasis is on harm reduction – both harm to health (addiction, HIV infection) and to society (school dropouts, public nuisance, crime). This approach, which changes over time, puts the apparently stark contrast between ‘harm reduction’ and ‘prosecution’ into perspective.

The committee has used this idea of a dynamic drugs policy, whereby the purpose of various measures would be made clear, as a framework for its deliberations on the various elements of policy it was asked to consider. Since the theme of prevention was discussed in chapter 3, it will not be examined separately here.

5.2 Classification of drugs according to risk

Designation as ‘highrisk’

When a new drug emerges, it is assessed in terms of the risks it poses to public health. If those risks are considerable, it will be added it to Schedule I (unacceptable risk) or Schedule II (less serious risk) of the Opium Act, which effectively means it is banned. This allows criminal prosecution for possession, production and trafficking. The difference between Schedule I and Schedule II lies in the penalties imposed and in the specific acts that are criminalised (in this case preparatory acts).

Since 1976 the Opium Act has distinguished between drugs that pose an unacceptable risk to public health (Schedule I, which includes heroin, cocaine, amphetamines) and substances that pose a less severe risk (Schedule II, including cannabis). Since then, few changes have been made to the list. Ecstasy was added to Schedule I in 1988, GHB was added to Schedule II in 2002, and since 2008 fresh hallucinogenic mushrooms have been added to Schedule II, along with the dried version, which had previously been on Schedule I. Sentences for possession, production, selling and trafficking of drugs on Schedule I are considerably harsher than those for substances on Schedule II.

See the Opium Act Instructions (2000A019), and the Guidelines for Prosecutions under the Opium Act, soft drugs (2000R004) and hard drugs (2000R005). www.om.nl

The committee was asked to examine whether there is any reason to reconsider the listing of drugs on Schedule I or II. In response to this request, the committee gave more fundamental consideration to the question of whether the current system, with two schedules, is still appropriate. It identified a number of problem areas.

Updating and credibility

The question is whether the inclusion of various substances in the schedules is still consistent with our current knowledge of the harm they can cause to public health. We now know more than we did in 1976 about the short and longterm risks to individual physical and psychological wellbeing, to social functioning and to society, including those associated with substances such as alcohol and tobacco, which are not covered by the Opium Act. If we were to draw up such lists on the basis of what we know now, some substances would probably be categorised differently, or might not be covered by the legislation at all. Our understanding deepens, and substances change (the Dutch cannabis – or ‘Nederwiet’ – currently on the market is very different from that available in the 1970s and 1980s). Such changes are not, however, reflected in shifts from one schedule to the other, or the removal of substances from the schedules.

This failure to update the schedules may also be influenced by the government’s desire to send a message about harmfulness, in response to a particular incident, for example. This has happened recently in the case of substances like cannabis, ecstasy and hallucinogenic mushrooms, both here and in the United Kingdom. It is understandable that, on topical issues, politicians are keen to prevent people from gaining the wrong impression about the risks associated with certain drugs. However, if this occurs systematically, it can undermine the credibility and therefore the usefulness of the categorisation.

It is sometimes impossible to avoid imbalance, in cases where the Netherlands is obliged under EU or other international law to regulate certain substances under the Opium Act, even though they are rarely, if ever, found on the Dutch market, and the evidence of their potential harmfulness is not convincing.

Grey area between illegal and prescription drugs

The regime established under the Opium Act differs markedly from the system for prescription drugs. This can cause problems, since some prescription drugs on the market can be improperly used for recreational purposes, or to enhance performance. The applies for example to certain opiates, amphetamine derivatives, sedatives, tranquilisers and other substances used in psychiatric and psychological treatment. The dividing line between proper and improper use of prescription drugs is sometimes very thin, which makes it difficult to pursue a clear policy in such cases. There is also a very fine dividing line between the Medicines Act and the Opium Act. In the Netherlands, benzodiazepines are regulated by both Acts, because of their potentially addictive effect. The committee believes that the Opium Act is not the most appropriate instrument for regulating the prescription for medical purposes of drugs on the current schedules. But nor does the current Medicines Act provide a basis for determining when medical use becomes illegal consumption. These are issues to which the current legislation is unable to provide an appropiate answer.

Substances marketed as prescription drugs are thoroughly researched and their pharmacological effects tested. Such research takes a great deal of time, and is very costly. Once a substance is on the market, it has to be monitored for years in case it causes side effects. In the case of illegal drugs, the substance is already on the market, and there are no producers who are prepared to invest in a research programme. Nevertheless, governments do put money into researching the harm caused by drugs. Collaboration with pharmacological researchers might produce benefits in terms of the knowledge acquired and of efficiency. The Coordination Centre for Assessment and Monitoring of New Drugs (CAM) could then use the knowledge thus acquired to assess whether the substances should be scheduled (or moved to another schedule) under the Opium Act.

Broader assessment framework

The guiding principle for scheduling substances under the Opium Act is their harmfulness to individual and public health. The committee believes it is important that harm to society also be considered.

In 2007 a paper was published in the medical journal The Lancet about the relative harm caused by various substances. A panel of experts assessed 20 substances, considering not only pharmacological aspects, but also harm to society. Heroin came top of the British experts’ list of most harmful substances, followed by tobacco and alcohol. LSD came bottom of the list. The Dutch National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM) performed a similar study for the Netherlands, at the request of the Minister of Health, Welfare and Sport. Again, a panel of experts assessed 19 substances, including tobacco and alcohol, in a similar way. Unlike the British experts, however, they based their assessment on reports compiled on each of the substances on the basis of literature studies. Nevertheless, the results of the two studies are very similar. In this country, too, heroin and tobacco came top of the list, cannabis was in the middle, and hallucinogenic mushrooms came bottom. The list of substances studied in the Netherlands differed slightly from the British list in one respect: it included only substances available on the user market (the Dutch study covered hallucinogenic mushrooms, for example, but not barbiturates).

The convergence in the results of these two entirely independent studies has prompted the committee to conclude that the harm criterion must not be restricted to the toxicological risk, and that substances must be assessed in terms of relative risk if the lists are to be consistent. It is not wise to immediately schedule emerging substances under the Opium Act as a precaution, if only because – as we observed above – such a decision can rarely be reversed. This may well be unavoidable in the case of emerging drugs whose risks are not well known, however. Later in the dynamic process of drug use, the risks can be better assessed as more (and more reliable) data become available.

It is thus important that the CAM, which is responsible for subjecting drugs to a multidisciplinary risk assessment, use a fourdimensional assessment model. Besides risks to individual and public health, it should also consider public order and safety, and criminal involvement. This model, which was recently applied to an assessment of cannabis, might form the basis of a broader assessment framework which would allow reassessment of substances after a certain time, once the actual risks were known. This might lead to a different decision on scheduling under the Opium Act.

A single list?

The categorisation into two schedules under the Opium Act suggests – wrongly, as this was never the intention – that there is reason to judge systematic criminal dealing in soft drugs differently from dealing in hard drugs. The major differences in sentencing regimes suggest that dealing in soft drugs is not as bad as dealing in hard drugs. In practice, however, it is not possible to draw such a distinction when it comes to production and trafficking: criminal organisations can easily move between substances on Schedule I (e.g. cocaine trafficking) and Schedule II (growing cannabis). The committee would call for the distinction to be abolished, and for a single list of banned substances to be used. This would also have the advantage of abolishing differences in the degree to which preparatory acts were regarded as a criminal offence.

A move to a single list, better substantiated than the current ones, would not prevent the Public Prosecution Service allowing for some differentiation in practice in its guidelines (as is already the case under the Opium Act). The extent to which a specific drug is tackled as a priority under the criminal law, and how, should be determined less by its inclusion in a particular list, and more by its phase in the epidemic cycle. This can best be addressed at a practical level, rather than in legislation.

It might be possible to institute some kind of hierarchy in the single list, for substances that require an exemption because they also need to be used in medical practice (Medicines Act), or on other grounds. The system must be flexible, as developments in drug use occur too rapidly for policy ever to keep pace.

Conclusions

The committee has its doubts about the current Opium Act with its two schedules, and suggests that a single list be introduced. However, such a change would involve complicated legislative drafting which is neither part of the committee’s mandate, nor achievable before the deadline. The committee only recommend that a committee of experts be established to look into this matter in more depth, and produce solutions and proposals for amendments to the legislation.

5.3 Limiting damage

Once a certain level of drug use is reached, despite efforts at prevention and limiting its spread, it becomes extremely difficult to achieve any effect through policy measures. Society will then suffer the potentially harmful effects of use for some time. Damage to users, however can be prevented or reduced (harm reduction). Another form of damage is the crimes committed by users.

Harm reduction

Policy has been shown to have an impact on the health problems associated with substance use. Examples of harm reduction strategies include needle exchanges (to prevent infectious disease, HIV/AIDS, hepatitis), treatment with methadone (to prevent overdoses and reduce mortality rates), medical treatment with heroin for chronic addiction, and the setting up of injecting rooms (to provide a safe environment for users). These strategies work, and are being adopted by more and more countries. The committee believes that this policy has proved its worth and should be continued. Nevertheless, certain practical improvements could be made, for example in the quality of methadone treatment. The availability of extra financial resources since mid2008 has boosted efforts to improve matters.

The committee would however like to highlight one problem area. Enforcement officers sometimes use employ farteaching methods in pubs and clubs, such as drug searches on entry, while health care professionals are also present to warn of the risks associated with drug use. In such instances, the government shows two different faces – both help and punishment – and this reinforces neither its message nor its credibility. The committee believes that neither a strict nor a relaxed approach deserves priority. What is needed is a coordinated approach based on the idea of a dynamic drugs policy. Sometimes strict will be appropriate, while at other times a more relaxed approach can be taken. Which approach is most appropriate will have to be decided by the tripartite authorities, based on input from local health care services.

Tackling drugrelated crime

In the cycle of heroin use, which arose in the 1970s and is now well past its high point, it took a long time for a structural approach to be taken to addicts who committed multiple offences and caused a public nuisance. The onesided approach focusing largely on harm reduction, prompted partly by a shortage of prison cells, has now made way for a much more rigorous approach in which the efforts of the criminal justice authorities are tied to those of the care services, and coercive measures such as compulsory treatment orders for addicts – and later detention in Persistent Offenders Institutions – have been introduced, alongside programmes such as medical treatment with heroin. If nothing else helps, addicts may be detained under the Psychiatric Hospitals (Committals) Act. In hindsight, such an approach would have been useful at an earlier stage, which shows that, when drug use and alcohol consumption are associated with crime, it should be tackled rigorously, not merely glossed over.

Individuals must be made aware that, if they use substances (alcohol and prescription drugs, as well as illegal drugs), they can pose a danger to others. This should make users extra cautious, and education campaigns should be used to persuade them of the burden of this responsibility. Committing a crime under the influence of alcohol or drugs (including prescription drugs) counts as an aggravating circumstance, since the individual should be aware of the fact that substance use is associated with increased risks.

5.4 Care of addicts

Addiction care in the Netherlands has been reoriented away from social welfare toward health care, with the aim of providing both care and cure. Addiction is firmly entrenched in both body and mind, and major improvements are difficult to achieve. The margins within which health care services can operate are therefore very narrow. The committee has the impression that addiction care services exploit the available potential well, in the case of adult addicts at any rate. The sector has clearly professionalised in recent years, partly as a result of the introduction of protocols as part of a programme entitled Results Score, and of a more evidencebased approach. More emphasis on addiction among minors and on services outside the addiction care sector (municipal health services, general health care services, youth care services, forensic care) is urgently needed, and there is much room for improvement in this area.

The organisation of addiction care

Care of addicts has been transformed from a patchwork of smaller and larger institutions into ten large institutions that provide not only addiction care, but also mental health care services and community shelters. They were set up in response to the introduction of the Health Care (Market Organisation) Act. This brought more care providers onto the market in 2006, increasing the supply of interventions by private service providers. They focus mainly on people with addiction problems who are still fully or largely able to function in society. This makes their treatment prospects much better than those of the generally socially excluded clients of regular addiction care services or other public health care sectors. There are no figures for the amount of private care on offer, because such institutions do not participate in the national registration system as regular addiction care providers do.

The greater focus on market forces and client orientation brought about by the Healthcare Insurance Act also appears to be having an impact on regular addiction care services. They are now able to respond more rapidly to requests for help (as in the case of GHB and gaming addiction). On the other hand, the market orientation appears to have encouraged publicly financed institutions providing care for addicts to regard each other as competitors, which has made them more reluctant to share information and research results.

Complexity

Client organisations do not have the impression that addiction care has become more accessible. They have found less flexibility and a greater tendency to take a blinkered view. Client representatives also say that addicts’ partners and families have little involvement in their treatment. This reduced flexibility will have been caused partly by changes to the healthcare system and the creation of larger merged institutions, which has made the funding of regular addiction care more complex in recent years. Care of a single client sometimes has to be paid for via several schemes: health insurance, the Exceptional Medical Expenses Act, the Social Support Act and, more recently, by the criminal justice authorities. Each system has its own criteria and registration procedures (e.g. Diagnosis Treatment Combinations, or DBCs), which has not only increased the administrative burden, but has also created barriers that hamper cooperation. In many cases, though clients can be rapidly diagnosed thanks to a central intake and needs assessment procedure, it has been suggested that some then find themselves on internal waiting lists for treatment for up to a year.

By extension, policy cooperation between addiction care institutions and other services (criminal justice authorities, municipalities, care administration offices, police, labour organisations) is also still problematic, as a result of this blinkered attitude. Treatment should include interventionist care, with a single therapist acting as liaison for the client. The treatment must therefore be multidimensional. Funding flows should break down rather than reinforce the barriers between different care sectors. The committee regards it as undesirable for different government departments (Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport, Minister for Youth and Families, Ministry of Justice) and other authorities to pursue their own policies when it comes to recognising, planning and funding different forms of treatment and institutions, for example.

The committee simply intends to highlight a number of important problems and suggest possible solutions here. In areas where it has argued for an integrated approach to the problem among young people (chapter 3), in particular, gaps in the treatment of young people with addiction and other problems, must be taken seriously and where necessary remedied with the use of court orders. In view of the short time available to complete its task, the committee had no opportunity to devise and test possible remedies.

5.5 Tackling the illegal market

Wherever there is a certain demand for certain drugs, an illegal market emerges to supply them. The committee was asked to consider what it would take to reduce the Netherlands’ role in the production, transit and distribution of ecstasy, cannabis and cocaine.

Approach to the market

During the phase in which a new, harmful drug appears on an illegal market, this market has yet to crystallise. From the point of view of a dynamic drugs policy, the priority in this initial phase is to discourage users and influence availability (accessibility/price) to such an extent that use becomes less attractive. This requires an assertive approach to minimise the spread of the drug, with a view to limiting longterm damage, and avoidance by the government of any signals that might be construed as approval or tolerance.

Once a certain level of drug use has become established, it is difficult to affect the supply of drugs enough to reduce demand. In the case of legal products, increasing the price can affect demand, as with alcohol and tobacco. The same will also be true of illegal drugs. Nevertheless, supplyside measures have little effect, because the market responds to barriers by seeking other ways of reaching the consumer. In other words, the market structure adapts to any change in conditions.

It has, for instance, been suggested that a prolonged period of low priority in terms of law enforcement in the cannabis market, followed by a period during which mainly smallscale growers were tackled, fostered the largerscale organisation of the market. This may be the case, but the idea that measures to tackle the illegal drugs market somehow ‘created’ organised drug crime is incorrect. It already existed on a large scale before efforts to tackle it got under way.

There is also evidence that some production of ecstasy and cannabis has been displaced to other countries in response to stricter enforcement in this country. A displacement effect to other trafficking routes has also been observed in the case of cocaine, resulting from the more rigorous checks in the Antilles and at Schiphol. A certain level of drug use in this country and elsewhere, therefore, combined with general infrastructural factors beneficial to the illegal drugs market in the Netherlands, make it difficult for the authorities to have any substantial influence on the supply market for drugs.

This economic perspective means a certain degree of modesty is called for with regard to the potential impact of government measures on the supply and distribution of drugs in these later epidemic phases. The emphasis then has to shift to controlling the potential side effects: illegal dealers amassing wealth and influence, using violence and intimidation to control the market, and corrupting officials, commercial service providers and companies.

A disorganised government against organised crime?

The committee has observed a sharply increased focus on and greater investment in controlling the illegal market for drugs. The drugs trade and the production of ecstasy have for many years been key priority areas for the police and criminal justice authorities. Since the facts regarding organised cannabis growing were recently established, investigation of such operations has been given high priority, and measures have been introduced to tackle the worst cases. The committee regards this as a positive and necessary development, as there was much ground to be made up in this area. Recently, too, albeit late in the day, attention has been focused on the worst excesses associated with this phenomenon: murder, torture, intimidation, bribery and money laundering via legitimate enterprises.

In this connection, the role of ‘grow shops’ in the production of and trade in cannabis requires particular attention. These enterprises – around 300 in number – have a key role, not only in providing material to home growers, but sometimes providing all the equipment needed on condition that the resulting cannabis harvest is supplied in its entirety to the grow shop. The committee believes that their role must be reduced and that grow shops, like coffee shops, should be permitted only with a licence from and under the supervision of the local authority. The committee understands that the Minister of Justice is now working on a legislative proposal concerning the status of grow shops.

The Programme of Action on Organised Cannabis Cultivation was launched in early 2008, shifting the focus deliberately to the criminal organisations behind commercial cannabis growing operations. The programme was a response to the violent crime and huge profits associated with them, and the links between illegal and legitimate enterprises, which poses ethical risks. The aim is not only to tackle individual offenders and dismantle criminal organisations, but above all to destroy the structures that have allowed this development to occur.

The programme is part of an effort to strengthen measures against organised crime, as set out in the government’s policy programme. These efforts are based on the principle that effective measures against organised crime require more than just criminal investigation and prosecution. They need joint action by municipalities, the Tax and Customs Administration, the police and the criminal justice authorities, sharing information and taking coordinated action.

(see www.justitie.nl)

The committee believes that measures to tackle organised crime are still inadequate. Where crime becomes organised and professionalised in illegal markets, the government must not lag behind because of a lack of coherence. There has been a positive trend in recent years away from pursuing and arresting individuals and confiscating drugs towards a more wellconsidered, ‘programmatic’ approach, linking criminal justice, administrative and fiscal measures to create systematic obstacles to organised crime.

This type of approach was first tested in a human trafficking case (the ‘Sneep’ case) and is now being applied to organised cannabis production. The authorities collaborate on such cases with energy suppliers and insurance companies, for example. Provided this approach is applied consistently and with enough support it could lead to a considerable reduction in cannabis production and the associated violence, corruption and accumulation of influence as the proceeds of crime are invested in legitimate enterprises.

The committee believes that we need a consistent approach to organised crime. Efforts to introduce such an approach are only in their early stages, however. We currently have only ‘test beds’ for ideas that still have to be translated into regular practice.

The committee would like to raise a further, more important, point. A sectoral approach (e.g. to cannabis growing) might overlook the links between different sectors of criminal activity, making it less effective than an approach where the spotlight is focused on criminal associations that constitute the biggest threat. Experience has shown that a firm, intensive, persistent and intelligent approach can substantially reduce the risks associated with organised crime,. The committee would therefore recommend such an approach be adopted.

Law enforcement climate

One factor in the Netherlands’ position is the relatively lenient law enforcement climate. Although there is no evidence that a more lenient enforcement climate fosters ordinary crime such as theft and vandalism, drug dealers are more calculating, and this probably does not apply to drug crime. An enforcement climate that differs sharply from other countries could quite possibly be a factor in decisions as to whether to become involved in the illegal market as a dealer, courier or intermediary.

Earlier in this chapter the committee stated that there is reason to reconsider the difference in sentencing under Schedules I and II of the Opium Act, as this regime might hamper a dynamic drugs policy. After all, different approaches are needed in different phases of the epidemic, and organised dealing is often not limited to a single substance. The committee therefore believes that there is reason to review enforcement and sentencing for drug trafficking, as advised in the Public Prosecution Service’s guidelines and elsewhere, partly with a view to convergence with other countries. In particular, a greater threat of prosecution and punishment could be introduced for supplying or even ‘pushing’ drugs to young people, or supplying drugs commercially through courier services and the media.

Finally, the committee believes that offenders, whether in prison or not, must no longer be able to continue their role in drug dealing from a distance (or, in the case of electronic tagging, from their home). This undermines the deterrent effect of custodial sentences and the credibility of and confidence in the public authorities.

5.6 Authorities

The committee is convinced that any dynamic drugs policy must be an integrated policy, in which health care, crime fighting and measures to reduce public nuisance complement each other, and the emphasis shifts depending on the current phase of use. Public health policy might act as a coordinating force, and provide anchorage, but no single policy area could claim dominance. The committee is interested not so much in debates about what aspect is most important, as in adequate solutions to the problem at hand. It believes that the tripartite authorities at local/regional level – the local authority, Public Prosecution Service and police – must also receive input from the municipal health service on this matter.

More needed at national level

The committee has already observed that little has been done to update drugs policy since the drugs policy document published in 1995. Despite occasional studies and monitoring reports, we know too little about production and trafficking, in particular. This is particularly true of the police and criminal justice authorities. In view of the need for a dynamic drugs policy, and given the complexity and extent of developments in this area, this level of ‘policy neglect’ is unacceptable.

The committee saw many signs of inadequate collaboration between policymaking bodies. Its impression is that in some cases, separate policy regimes exist alongside and in isolation from one another, and operate independently. There has been too much indifference where consultation and action would have been more appropriate. The Ministry of Justice and the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport each have their own research policy, for example (implemented on their behalf by the Research and Documentation Centre or WODC and the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development or ZonMw respectively), while a joint framework might be more efficient, effective and objective. While an institution like the National Drugs Monitor (NDM) is important, it has not been able to give us any idea of the actual developments behind the figures, such as those occurring in coffee shops, and in the world of organised crime.

Drugs authority

The committee has ascertained that a great deal remains to be done to adapt certain areas of drugs policy to changed circumstances, and to make it sensitive and responsive to the dynamics inherent in the world of drugs. It believes that the current configuration, with responsibility for policy divided among several ministries (not just the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport and the Ministry of Justice, but also the ministries of education, foreign affairs etc.) cannot be relied upon to develop and draw lessons for policy. The committee therefore recommends that coordination and direction be placed in the hands of a single authority (possibly consisting of senior civil servants), which has the power to develop and monitor drugs policy, and to take budget decisions where necessary. This might be a temporary arrangement, set up to develop policy along the lines recommended by the committee. However, it would make more sense to have a permanent body with clear political leadership, not least because of the importance of international coordination.

The committee does not regard it as its responsibility to set out how this body should be structured, but would call for the currently isolated policy regimes to be integrated. Clashes of ideas and interests are important in any policy learning process, but as a result of the current division of responsibilities they tend to lead to paralysis and a lack of responsiveness. The committee therefore believes that a less than welldefined body like the current interdepartmental steering group on drugs has insufficient administrative clout. The scale and severity of the problem justifies a more binding level of ambition, based on political leadership, which would also encompass forging ties with neighbouring countries and with the US. Politicians will have a role in resolving impasses and providing strong guidance. The ‘drug czar’, a highranking politicallyappointed official with his or her own office, for which countries like Germany and France (MILDT) and the US (ONDCP) have opted, might serve as an inspiration, precisely for the reason the committee has just noted. Whatever form is chosen, the essence is that sufficient political and administrative power must be mobilised for the body to be able to develop drugs policy further and keep its finger on the pulse (monitoring, research).

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|