9 Interventions in blood -borne diseases“ – needle exchange, prevention, testing advice, injection rooms

| Reports - Models of Good Practice in Drug Treatment |

Drug Abuse

9 Interventions in blood -borne diseases“ – needle exchange, prevention, testing advice, injection rooms

Guidelines for treatment improvement

Moretreat-project

CIAR Hamburg Germany

October 2008

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

HEALTH & CONSUMER PROTECTION DIRECTORATE-GENERAL

Directorate C - Public Health and Risk Assessment

The content of this report does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the European Commission. Neither the Commission nor anyone acting on its behalf shall be liable for any use made of the information in this publication.

Content

9 Interventions in blood-borne diseases“ – needle exchange, prevention, testing advice, injection rooms

1. Interventions in blood-borne diseases

1 Needle exchange services

1.1 Introduction

1.2 Research evidence base – key findings

1.3 Recommendations

2 Drug consumption rooms

2.1 Introduction

2.2. Research evidence base – key findings

2.3 Recommendations

3 Testing and vaccination

3.1 Introduction

3.2 Research evidence base – key findings

3.3 Recommendations

4. Information and education

4.1 Introduction

4.2. Research evidence base (key findings)

4.3 Recommendations

References

1. Interventions in blood-borne diseases

Drug users and in particular injecting drug users (IDUs) are at risk of infections with blood-borne diseases (BBD). These include especially Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and hepatitis C (HCV), furthermore other hepatitis infections (HBV and HAV) and tuberculosis, but other infections (both bacterial and fungal infections, such as STIs) are rather common as well. HCV is a virus with potentially devastating hepatic complications, which will become chronic in about 80% of the infected persons, while 20% will clear the virus (Wright and Tompkins 2006).

In 2005 there were around 3,500 new diagnoses of HIV in the European Union which were traced back to injecting drug use, and estimations are that 200,000 persons are infected with HIV in the countries of the European Union (EMCDDA 2007a). The prevalence of HIV among IDUs differs between the countries and may range from almost zero up to 40% (EMCDDA 2007a). The prevalence of Hepatitis C (HCV) among IDUs ranges between 30% and 98% in the European Union (EU), while in the general population the prevalence rate is at around 3% (Wright and Tompkins 2006). Young IDUs become infected with HCV while still in the early stages of their drug using career (EMCDDA 2007a). In a large cohort with around 5.000 patients who took part in a “EuroSIDA” study, infections with HBV were present in 9 % and infections with HCV in 34 % of the patients living with HIV. The highest prevalence of 48% patients with HCV co-infection was found in Eastern Europe (Matic et al. 2008). The huge difference between HIV and HCV infection-rates is due to differences in the ways of infections. The Hepatitis C Virus is much more resistant than the HI-Virus and can survive even in dried blood for several days and weeks while the HI-Virus only survives few minutes in the air (Leicht and Stšver 2004). The exact ways of transmission for HCV are unknown in the single cases as not only needle sharing, but also sharing of other injecting equipment like spoons, filter, lighter, table surface are possible ways of infecting. Also the shared use of household items like scissors or toothbrush may cause an infection (Leicht and Stšver 2004). As injecting drug users often practice a rather unhygienic way of life, there are plenty of possibilities for infections.

The importance of the issue of harm reduction is also seen by the Council of Europe, which stresses in their recommendations the need for “information and counselling to drug users to promote risk reduction...” (Council of Europe 2003).

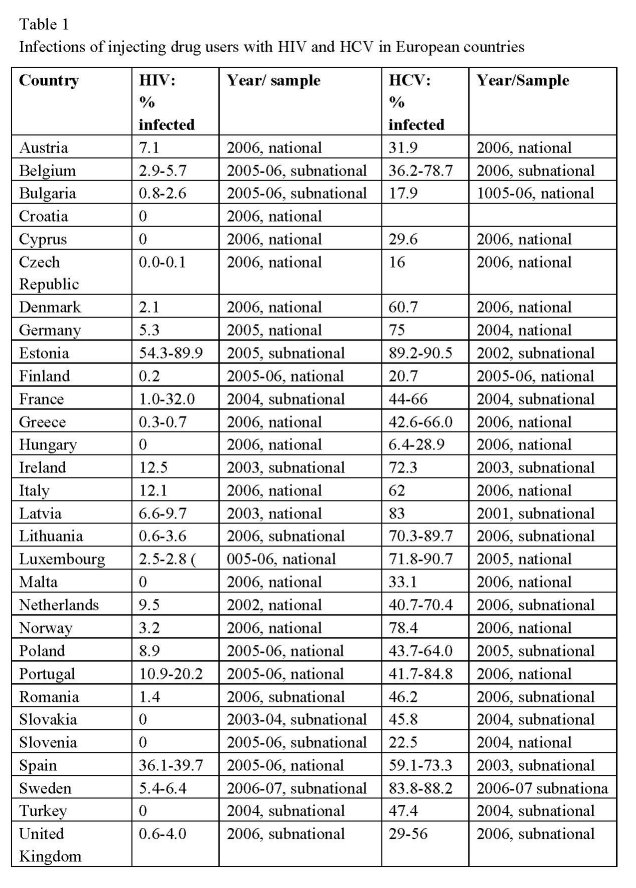

The table below gives an overview of prevalence rates for HIV infection and HCV antibody among injecting drug users (IDUs) in European countries:

Due to different sources and study designs the infection rates must be interpreted with caution and can not be compared. Some numbers refer to national surveys, others to regional studies, and some are based on small samples only (EMCDDA 2007b; EMCDDA 2007c).

Injecting drug use is one of the main risk factors and prevalence of BBD is high among IDUs (National Treatment Agency 2002).There are a number of risk factors which correlate with the likeliness of infections: age, years of intravenous use, individual riskconcept/willingness, depression, experience with violence and sexual abuse, and especially number of imprisonments, insecure living conditions and low education level (Leicht and Stšver 2004). Independent risk factors for HCV seroconversion seem to be a history of imprisonment, history of needle/paraphernalia sharing and polydrug use (Wright and Tompkins 2006). But not only injecting poses the risk of blood-borne transmission, crack cocaine smoking can have the possibility of transmission as well and therefore needs to be taken into account (Shannon et al. 2006) . Living conditions and cultural traditions in the drug scene do influence drug using and risk behaviour and need to be addressed in a successful harm reduction approach (Leicht and Stšver 2004).

Increased investment in harm reduction measures may result in decreased HCV transmission (Hope et al. 2001).

With respect to the prevention blood-borne diseases treatment improvement guidance have been developed for the following four intervention types:

• Needle exchange services

• Consumption rooms

• Testing and vaccination

• Information and education

1 Needle exchange services

1.1 Introduction

Needle exchange services are an important measure to reduce blood-borne diseases.

1.1.1 Definition

Needle and syringe exchange services have been developed as an integral part of harm reduction policy in order to respond to various harms related to drug use (Ritter and Cameron 2006). Within this context needle and syringe exchange services aim in general at harm minimisation and risk reduction. In particular they play an important role for preventing blood-borne diseases, especially as regards averting infections with HIV and hepatitis (Des Jarlais et al. 2002; McVeigh et al. 2003; De la Fuente et al. 2006). The distribution/exchange of sterile injection equipment by specialised drug services or pharmacies is an essential public health measure to reduce blood-borne diseases and prevent drug-related death (National Treatment Agency 2002).

1.1.2 Context

In Europe, clean syringes and needles are provided by all Member States except Cyprus. According to the EMCDDA (2007) several countries (Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Austria, Slovakia, and Finland) reported an increase in the number of syringes distributed through specialised needle exchange services. In 2005 more than 23 million syringes have been exchanged, distributed or sold in the European Union (Statistical Bulletin, table HRS-1: 39423EN.html). In some of the European countries pharmacies take a pro-active position in distributing syringes to drug users. For instance in Scotland a network of 116 pharmacies distributed 1.7 million syringes in 2004. The majority of needle exchange services offer a safe disposal for the return of used injecting equipment. Since introducing needle exchange services it has become increasingly a general approach to provide additional sterile equipment such as swabs, filters, citric acid, water ampoules etc.

1.1.3 Philosophy and approach

In the last two decades, key elements for an effective response to infectious diseases among injecting drug users have been developed in European Member States. In particular the HIV/AIDS epidemic among homosexual and drug user communities in Western Europe in the early 1980s resulted in major changes in health and drug policy, and thus initiated the introduction of various harm reduction measures (McVeigh et al. 2003; Hamers and Downs 2004). From a global perspective Switzerland, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand and Canada were those countries that early adopted harm reduction measures (Kempa and Aitken 2004; Ritter and Cameron 2006). In recent years harm reduction programmes have become increasingly available in community in central and Eastern Europe, Asia and Latin America (Ritter and Cameron 2006).

Needle and syringe exchange programmes as one component of harm reduction started first in 1984 in The Netherlands. In the following five years sterile injecting equipment was supplied in further five European countries (Spain, UK, Sweden, Germany, Denmark and Czech Republic). During the 1990s the majority of European countries have established needle exchange services, and since 2000 nearly all European Union Member States run needle and syringe programmes either at drug agencies or by involvement of pharmacies or by mobile units.

In the beginning the main objective of needle exchange services was to prevent infections with HIV by making sterile injection equipment accessible to all drug injectors. The accessibility of needles and syringes aims at the reduction of risk behaviour such as sharing of injection equipment, and thus at the minimisation of the risk of blood-borne diseases.

Needle and syringe exchange services were developed within a comprehensive harm reduction approach covering as well substitution treatment, information and education, counselling and testing of infectious diseases, vaccination and treatment of infectious diseases. Access to this variety of harm reduction measures not only aims at the reduction of blood-borne diseases but is also targeting at the reduction of drug-related deaths and the prevention of overdoses.

However, even though the level of provision of sterile injecting equipment varies in the European Union, syringe exchange services are well established in almost all Member States.

1.1.4 Location

In Europe, the majority of needles and syringes are exchanged at drug agencies rather than at pharmacies. However, a few countries (such as ES, UK, NL, DK) show a wide geographical coverage of needle and syringe exchange through pharmacies. For those drug users not being in contact with other services pharmacies are a good location to dispense needles and syringes. In order to reach marginalised groups of drug injectors many countries have also established mobile needle exchange services (EMCDDA 2007a).

Up to now prison-based needle exchange programmes are rare and only provided in few countries such as Spain, Switzerland, Germany, Luxembourg and in a few countries of the former Soviet Union (Moldova, Belarus, Kyrgyzstan) (Stöver and Nelles 2003; Lines et al. 2006; EMCDDA 2007).

1.1.5 Aims of the intervention

Main aim of needle exchange services is to distribute or sell sterile syringes, needles to intravenous drug users. Along with the distribution a safe disposal of used needles and syringes has to be offered.

Needle and syringe exchange services are one cornerstone of harm reduction efforts aim at the prevention of risk behaviour (Ritter and Cameron 2006; Trimbos Institute 2006).

The major objectives of these services are

• to reduce the sharing of equipment used in drug preparation and injection (Morissette et al. 2007),

• to reduce the transmission of HIV, hepatitis B and C, and other blood-borne infections,

• to increase access to harm reduction,

• to offer advice and counselling on HIV and hepatitis and other drug-related health problems,

• to provide information and advice on overdose prevention and safe injecting practices,

• to encourage a reduction or cessation in unsafe sexual behaviour,

• to offer advice and counselling on social and welfare problems, and

• to ease access to treatment and provide referral to other specialist treatment services,

In general needle and syringe exchange services are designed to meet the needs of drug users who are unwilling or unable to stop injecting practices (Mullen et al. 2001). For this reason needle exchange service base upon a user-friendly, client-centred and confidential approach which aims at assisting service users to remain healthy.

1.1.6 Client group served

Needle exchange services provide easy access to all drug injectors. In particular they address those injectors not being in contact with other treatment services. There is evidence that a considerable number of users of needle exchange services do not make use of other local services (National Treatment Agency 2002). Needle exchange programmes have been shown to attract more severely drug dependent injectors who inject frequently, and engage in high risk activities such as for e.g. poly-drug use (Henderson et al. 2003). Needle and syringe exchange services do not reach all groups of injectors equally. According to research needle exchange services have huge difficulties to reach young drug injectors (Bailey et al. 2003), female injectors and intravenous drug users from ethnic minorities. In addition, needle exchange services seem to attract non-opiate injectors less than opiate injectors (National Treatment Agency 2002). A study from Scotland indicates that many of the young and relatively inexperienced intravenous drug users aged 16-19 years old shared injecting equipment, particularly spoons, water and filters. At the same time only a minority of the young injectors had made use of local needle exchange facilities (Stevenson et al. 2001). Similar results are reported from a Dublin study among 15-19 years old drug users who attended local needle exchange services for the first time (Mullen et al. 2001). In young drug injectors the prevalence of needle sharing increased after the first year of intravenous drug use. For this reason the authors recommended that needle exchange services are targeted to the needs of young injecting drug users and in particular to young female drug users. Accessibility to needle exchange services may reduce risk behaviour of young drug users. On the other hand there may be a certain group which will nevertheless practice risky injecting behaviour. Within this context a study among young injection drug users in San Francisco shows that despite access to and use of needle exchange facilities in a group of users sharing of needles still persisted (Hahn et al. 2001).

1.1.7 Exclusion

Usually needle exchange services address adult substance users while adolescents and young drug users less than 18 years of age must meet specific criteria in order to make use of needle exchange facilities. In the case of young injectors or minors the country-specific regulations for child protection have to be taken into consideration when offering needle exchange to them. Secondly attention has to be drawn to the minor’s ability to give consent for treatment. Due to research findings it is quite clear that on the one hand young injectors should be provided with sterile needles and syringes. On the other hand needle exchange should only be offered to those young people being at risk for significant harm. This means that the risk of providing needles and syringes to young injectors have to be lower than the risks which are related to not provide such a service (National Treatment Agency 2002).

1.2 Research evidence base – key findings

Evidence for needle exchange services has mainly been investigated by analysing the association between service utilisation and the reduction of blood-borne infections and risk behaviour including sharing of injecting equipment (Trimbos Institute 2006). The evaluation of needle and syringe programmes (NSP) is based upon a number of different methodologies such as pre-and post-NSP comparisons, comparisons of NSP-attendees versus non-attendees, cohort studies, case studies, population prevalence studies, and country comparisons. In addition, there are systematic reviews on international evidence found for harm reduction measures (Ritter and Cameron 2006), for hepatitis C prevention interventions (Wright and Tompkins 2006) and for needle exchange in prison (Lines et al. 2006). When NSP became increasingly available worldwide, a number of researches were undertaken in the late 1990s until the early years of 2000 which addressed the question of potential negative effects of needle and syringe provision. In this respect it was evaluated whether NSPs may in fact increase drug use and drug injection, and may attract drug users to initiate injecting. Research evidence shows that needle and syringe exchange does not result in these unwanted effects (Bluthenthal et al. 2000; Fisher et al. 2003; Ritter and Cameron 2006). There is also no evidence that crime rates increases in areas where needle and syringe programmes exist (Ritter and Cameron 2006). Evaluations of prison needle exchange programmes are consistent in their evidence that these programmes do not endanger staff or prisoner safety, do not increase drug use or injection and that return rates of used injecting equipment are quite high (in two German prisons about 98 %) (Jacob and Stöver 2000; Stöver and Nelles 2003; Lines et al. 2006). On the contrary, prison-based NSPs have a positive outcome for the health of prisoners (Lines et al. 2006).

1.2.1 Effectiveness of NSP on the reduction of blood-borne diseases

With regard to blood-borne diseases evaluation of needle and syringe provision focuses primarily on effects of this intervention on reducing HIV and hepatitis infections. Furthermore there are some studies evaluating the reduction of risk behaviour (e.g. needle sharing), and in recent years the question of NSP coverage attracts growing attention. As by nature evaluation of the NSP effectiveness lack of controlled trials with cohorts of drug users, evidence found in research remains insufficient and has to be interpreted cautiously (Heimer 2008). In consideration of methodological limitations most studies show that the increased availability of needle and syringe provision has contributed considerably to the control of HIV among drug injectors (Henderson et al. 2003; MacDonald 2003; Emmanuelli et al. 2005; Bravo et al. 2007). By examining changes in HIV infection rates research indicates evidence for needle and syringe programmes in contributing to a reduction of HIV incidence. In the UK, a survey based upon 50 drug services (including structured drug treatment and NSP) and data from an Anonymous HIV Prevalence Monitoring Programme found relatively low HIV prevalence among injectors in England and Wales. The low HIV prevalence rate of 3.6 % in London and 0.21 % for England and Wales is attributed to the introduction of needle and syringe programmes (McVeigh et al. 2003). A recent study from France (Emmanuelli et al. 2005) documented that between 1996 and 2003 the HIV prevalence among drug injectors decreased from 40% to 20% and in the same period a decrease in syringe sharing could be observed. These positive effects in health outcome are traced back to the greatly improved access to sterile syringes and substitution treatments. Studies from Canada (Guenter et al. 2000; Morissette et al. 2007) and California (Gibson et al. 2002) show as well that HIV prevalence remains low among attendees of needle exchange services. The Californian study compared the HIV risk behaviour of NSP clients with that of non-clients on basis of a prospective cohort of 259 untreated injecting drug users. 10.7 months after baseline the follow-up of the drug users was carried out. Analyses reveal that the use of NSP is associated with twofold benefits of decreased HIV risk behaviour (Gibson et al. 2002).

While research supports evidence for reduced HIV prevalence through needle and syringe exchange programmes, research on effectiveness of NSP for the reduction of HIV incidence shows controversial results (Amundsen 2006; WHO 2007b; Wood et al. 2007; Heimer 2008). A recent prospective cohort study among drug injectors in Vancouver, Canada, suggests limited evidence for preventing HIV infections. No lower HIV incidence rate were found for those IDUs reporting daily needle exchange use compared with those not using exchange services daily (Wood et al. 2007). However, this result was attributed to the higher risk profile of daily NSP users caused by cocaine injecting. An ecological study found by regression analysis, that in cities where needle and syringe programmes were introduced, HIV prevalence decreased by 18.6% per annum, while in cities without those programmes, the HIV prevalence increased by 8.1% per annum (MacDonald 2003). Needle exchange programmes seem to be less effective in preventing hepatitis C infection. Despite frequent use of needle and syringe programmes infections with HCV remain still high in many countries. In France, HCV prevalence among drug injectors using needle exchange services was 60-70% (Emmanuelli et al. 2005). Similarly the systematic review of American and Australian studies conducted by Wright and Tompkins (2006) did not support evidence for the reduction of HCV incidence. On basis of comprehensive observation studies from Scotland the review found statistically significant reduction of HCV prevalence shortly after introduction of needle exchange programmes in the 1990s, but in the following years the declining trend in prevalence did not continue. Only among drug users aged over 25 there was a reduction in HCV infections. The authors concluded that needle and syringe programmes reduce the prevalence of HCV even though prevalence remains still high (Wright and Tompkins 2006; Wright and Tompkins 2007). These results have been confirmed by an Australian study which found a 63 % reduction in HCV incidence in 1995 but only a 50 % reduction in 1997 (MacDonald et al. 2000). From research literature three major reasons can be identified for the slow decrease of HCV prevalence which are: the continued risk behaviour, the infrequent use of services providing sterile injecting equipment and the high risk profile of NSP clients. HCV infections among intravenous drug user remain high due to persistent sharing and reusing of syringes and needles (Morissette et al. 2007) and due to frequent sharing and reusing of paraphernalia such as filters, spoons and water (Griesbach et al. 2006). Results from a Canadian study show that consistent users of sterile syringes are older than 30 years of age, inject alone, and have less difficulties to obtain sterile syringes (Morissette et al. 2007). Results from an American study suggests that young IDUs aged 18-30 are likely to be infrequent users of needle and syringe programmes or do not use the services at all (Bailey et al. 2003). However, research also suggests that even among regular users of needle exchange programmes, HCV prevalence remains high because of their high risk consumption behaviour such as frequent i.v. drug use, polydrug use etc. (Wright and Tompkins 2007). In view of preventing blood-borne diseases changes in risk behaviour can be regarded as an important outcome. A number of international research provided evidence for minimising risks related to intravenous drug use. A study on HIV risk behaviour among clients of syringe exchanges in five Central/Eastern European cities (Des Jarlais et al. 2002) shows: 1 to 29 % of the respondents reported injecting with needles and syringes used by others in the past 30 days. This number represents statistically significant reductions compared to reported 7 to 47 % syringe sharing in the 30 days prior to first use of the syringe exchange. Further research designs using pre-and post-comparisons of attendees support evidence that the use of needle and syringe exchange is associated with reduction in risk behaviour, in particular as regards borrowing and lending of used injection equipment (Bluthenthal et al. 2000; Gibson et al. 2002; Hutchinson et al. 2002; Bailey et al. 2003; Henderson et al. 2003; Ritter and Cameron 2006; Bryant and Hopwood 2008). For example Bluthenthal, Kral et al. (2000) found in their prospective study in 60 % of high-risk drug users a protective effect of NSP use against needle sharing. However, increased access to sterile needles and syringes plays an important role for risk reduction (Hutchinson et al. 2002; Bravo et al. 2007).

A recent study from Spain shows that increased access to sterile syringes resulted in an overall transition from injecting heroin or cocaine to smoking these substances (Bravo et al. 2007). A 12-month follow-up study from the United States indicates evidence for the change in drug use frequency and enrolment and retention in methadone drug treatment (Hagan et al. 2000). Intravenous drug users who make use of NSP were more likely than non-attendees to report a substantial reduction in injection, to stop injecting, and to remain in drug treatment. New users of the needle exchange services were five times more likely to enter drug treatment than never-exchangers (Henderson et al. 2003). In general, effectiveness of needle and syringe programmes is affected by the setting (community, prison), location (urban, rurual), client group served and by availability and accessibility of the programme. As regards availability a survey among drug services in Eastern Europe and Central Asia resulted in a sub-optimal provision of NSPs (Aceijas et al. 2007). Two recent studies address the question of the required coverage of needle and syringe programmes in order to substantially reduce HIV transmission (Vickerman et al. 2006; Heimer 2008). Both studies raise the problem of the definition of coverage. Coverage could be the number of syringes distributed per injector or the proportion of IDU population reached by the services. Vickerman et al. (2006) used a mathematical model to determine the coverage which is based upon comparison of the IDU populations in United Kingdom and Belarus, while Heimer (2008) used data on NSP clients, syringes distributed and AIDS cases from New Haven and Chicago. The paper of Vickerman et al. (2006) assumes that increasing syringe distribution coverage from a low level will have little effect on HIV prevalence until a minimum coverage of 20 % is reached. Even with a 40 % annual rate of cessation of injecting drug use, HIV prevalence would decrease only very slowly unless NSP coverage increased to the minimum level. The study of Heimer (2008) reveals that coverage of individual drug injectors rarely exceeded 10 % but even modest coverage rates have found to be effective in reducing HIV infections.

1.2.2 Effectiveness by treatment setting

Needle exchange services can be an important bridge to drug treatment. Research shows that the use of needle exchange services contributes to the entry into treatment such as detoxification and/or methadone maintenance (Henderson et al. 2003; Samet et al. 2007). For this reason treatment settings are recommended which offer a range of services to drug injectors. In rural areas the availability of outreach services is considered to be an important way of improving accessibility of sterile needles and syringes (Griesbach et al. 2006). Outreach services are seen as to be more successful in reaching women injectors and specific risk groups such as sex workers, homeless drug users and migrants. The most common settings of needle exchange base upon face-to-face distribution like in drug agencies, pharmacies, mobile services and outreach work. However, there is not much research on the effects of the different settings. A study from Sydney compared characteristics clients of NSP and pharmacies located in the same geographical area (Thein et al. 2003). Both client groups were similar in being mainly male, on average 30 years old and starting first injection at age of 18. Almost half of the respondents made use of both NSPs and pharmacies. Differences in the characteristics were found as NSP clients were more likely to report imprisonment, daily injection and sharing of injection equipment. Pharmacy clients were on the other hand more likely to report amphetamine use, and to share spoons and filters. In a number of European countries and elsewhere needle exchange services are complemented by syringe dispensing machines. In Europe, research regarding the usefulness of these machines is lacking. However, there is a current Sydney study that has evaluated provision of syringe dispensing machines (Islam et al. 2008). Apart from technical problems with the machines (broken, not in right place etc.) a considerable number of intravenous drug users made use of dispensing machines when other agencies for accessing sterile injecting equipment are closed. In particular in order to avoid stigma drug users less than 30 years of age seem to prefer syringe dispensing machines.

1.3 Recommendations

1.3.1 Location

In order to provide easy access to needle and syringe exchange services there should be a comprehensive range of these services on local level, including rural areas. Ideally needle and syringe exchange services have to be made available in:

• specialised drugs agencies or other specialised health services,

• community pharmacies,

• mobile needle exchanges,

• prisons, and

• through outreach workers

• slot machines/automats – 24h access. Also in or near treatment agencies (like detoxification centre) it can be advisable to offer needle and syringe exchange services.

1.3.2 Staffing and competencies

Professional competencies in needle and syringe exchange include knowledge about injecting patterns and the provision of harm reduction advice in terms of safer use. (National Treatment Agency 2002). In specialised drug agencies or needle exchanges medical staff such as nurses should be employed in order not to only provide injecting equipment but also to treat minor infections or offer basis health checks. To enable staff of specialised needle exchanges in dealing with health issues they have to be provided with training. Even though additional health services may be limited in some settings, and in particular in pharmacies, it is recommended to provide harm reduction advice together with clean injecting equipment if possible. The effect of needle exchange on reducing blood-borne infections can be improved by reinforcing messages on safer injecting. In France, where pharmacies play a major role in provision of sterile needles and syringes staff of pharmacies had been trained for participating in a decentralised exchange programme (Bonnet 2006). Pharmacists distributed an injection kit for free to IDUs, and also informed them of the risk of HCV infection and encouraged screening. The improvement of the relationship between IDUs and pharmacists has been shown to increase access to the healthcare system. If additional health services cannot be provided to drug users it is recommended to refer drug users to agencies where these services are available.

1.3.3 Treatment environment and holistic treatment and care

Good practice is to provide services and interventions beyond the simple distribution of sterile needles and syringes (Griesbach et al. 2006; EMCDDA 2007; Samet et al. 2007). In most European countries it is common to integrate needle and syringe exchange within other services provided by drugs agencies. Thus the distribution of sterile injecting equipment is combined with advice, risk counselling and also with referral of drug users to brief interventions and structured treatment. In terms of holistic treatment needle and syringe exchange services should assess and raise awareness for risk behaviour among clients, motivate them for testing of blood-borne infections and vaccination. Furthermore it is best practice to provide primary healthcare for minor infections, offer training in overdose prevention, and to provide housing, social welfare or legal advice.

1.3.4 Access

Needle exchange services are to be made as accessible as possible with no or low thresholds for eligibility. This includes drop-in service, no waiting list, minimal identification requirements and informal relationships with staff. Needle exchange services are open-access services to which drug injectors can self refer. Trained professionals such as nurses or social workers play a key role in encouraging clients to make use of other local health and treatment services (Mullen et al. 2001; National Treatment Agency 2002). Needle exchange services have also to be accessible to young injectors by minimising barriers to contact with services. With respect to young injectors, in particular those under age of 16 it is recommended that a designated staff member with training and knowledge in issues of young people carries out an assessment. Research has underlined that frequent attendees of needle and syringe programmes show best outcome in terms of risk reduction. For this reason services providing sterile injecting equipment should improve efforts to reach injecting drug users who do not use the services.

1.3.5 Assessment

A comprehensive assessment of needle exchange users is not recommended as it may constitute a barrier to service utilisation. However, it is good practice to carry out a basic assessment of the clients on their first visit of the service. This initial assessment is brief and includes information on:

• drug use profile and injecting history

• health status,

• risk behaviour, and

• history of referrals to treatment or other services. Clients are to be offered health checks and health information should be provided regularly. Harm reduction messages on risk reduction should be ongoing and include:

• risks of blood-borne infections (HIV, HBV, HCV), abscesses and other health damages caused by unsafe injecting practices,

• strategies to reduce the risk of overdose covering also poly-drug use and alcohol misuse,

• advice on safer injecting practice, alternatives to injecting and safer sex,

• testing for HIV, HCV and HBV, and vaccination for HBV,

• information about the range of services provided by needle exchange facilities, and

• information about drug treatment services and other health and social care services.

1.3.6 Management

Needle and syringe exchange services have to be designed in a way that is appropriate to meet the needs of the client. According to the evidence for needle exchange services it is important to implement a comprehensive approach by providing not only sterile injecting equipment but also by offering condoms, harm reduction advice, first aid and options for referrals to structured treatment (National Treatment Agency 2002). Provision of dedicated needle exchange services should be able to recognise people with physical or severe mental health problems, and to refer them to the most appropriate treatment. All service users are to be informed of drug and alcohol treatment programmes available in the region. With regard to community pharmacies, it is recommended that they should provide written information about harm reduction and harm reduction services. Wherever possible, direct information from the pharmacist or other pharmacy staff is recommended (Griesbach et al. 2006).

1.3.7 Pathways of care

As needle exchange services have been found to form a gateway to further treatment, clients have to be offered referral to a variety of structured treatment programmes such as brief motivational interventions, counselling, detoxification, substitution treatment with psychological care, and rehabilitation. However, formal collaboration between needle exchange services and drug treatment programmes could increase the proportion of drug injectors in treatment (Hagan et al. 2000; Henderson et al. 2003). With regard to health issues it is recommended to refer clients of needle exchange programmes to specialists providing HIV and hepatitis C pre-and post-test counselling. Referrals to specialists will only be required if the needle exchange service does not provide testing and counselling for blood-borne infections itself. Integrated care pathways also include offering training in overdose prevention to reduce drug-related deaths, and to provide information and advice for housing, social welfare and legal issues.

Best practice of non-pharmacy needle and syringe exchange services is to offer clients the opportunity to meet with a harm reduction worker or nurse on a drop-in basis in order to receive treatment for injecting injuries and care for minor infections. In addition needle exchange services should provide advice about safer injecting techniques and give information and counselling to service users on how to reduce behavioural risks and to avoid blood-borne infections. To increase access to sterile injecting equipment service users have to be provided with a list of other needle exchange facilities in the area.

A comprehensive public health approach has proved to be vital in reducing the risks of infectious diseases among drug injectors. Accordingly clients of specialised needle exchange facilities may require care co-ordination arrangements. This does not necessarily mean that an allocated care co-ordinator is available, but clients with complex needs have to be referred to appropriate services. Care coordination in terms of referrals requires networking and well established-cooperation between agencies.

1.3.8 Standards

Standards include assuring quality and efficiency of the needle exchange service. One approach to this task is to transform evaluation results into practice. In Europe a number of Member States already implemented harm reduction programmes by considering evaluation results (Trimbos Institute 2006). For harm reduction services it is recommended to develop specific working standards and methods – if not already existing – in order to ensure minimum quality standards (Trimbos Institute 2006). In addition, data should be collected in a standardised way by adopting the five key-indicators of the EMCDDA to monitor harm reduction. Outreach work is important to contact individuals or groups of drug users, who are not effectively reached by existing services or through traditional approaches. Guidelines for outreach work should be developed and appropriate training in outreach work should be offered.

1.3.9 Performance and outcome monitoring

Performance and outcome monitoring covers collecting routine information, monitoring and evaluating needle exchange services. Monitoring of performance includes to developing and implementing adequate evaluation protocols for the harm reduction services provided (Trimbos Institute 2006). An evaluation of the service may also include investigating of the clients’ satisfaction of the services provided (National Treatment Agency 2002). Outcome monitoring can be ensured by utilising either the data collection tools of the EMCDDA or by adopting the national minimum data system of recording client care. On a national level requirements for outcome monitoring might be stated in the service specification.

2 Drug consumption rooms

2.1 Introduction

Drug consumption rooms are an important measure to reduce the transmission of blood-borne diseases (BBD).

2.1.1 Definition

Drug consumption rooms (or Safer Injection Facilities or medically supervised injecting centres, as they are called as well), can be defined as places, where drug users can consume their pre-obtained drugs in a hygienic and non-judgemental environment under professional supervision (Trimbos Institute 2006). Drug consumption rooms offer a clean environment and sterile injecting paraphernalia, such as needles, spoons, and filters. The staff gives information on Safer Use, the transmission of BBD and how to avoid infections, and trains safer injecting practices. Furthermore, staff can give first aid measures when necessary and therefore reduce drug-related mortality (Hedrich 2004).

2.1.2 Context

Drug consumption rooms exist in the EU Member States Germany (25), Luxembourg (1), the Netherlands (ca. 40) and Spain (6) (EMCDDA 2007a). In Non-EU Member States they are available in Switzerland (13) (Springer 2003), and one each in Norway, Canada and Australia (Trimbos Institute 2006). After some trials and tolerated injecting rooms in the Netherlands and Switzerland, the first legal drug consumption room was opened in 1986 in Berne, Switzerland (Zurhold et al. 2001). Drug consumption rooms have been widely discussed in politics and often operated in difficult juridical circumstances. Still there are not many countries where drug consumption rooms are provided, despite the success of those existing. Policy makers are often reluctant to establish drug consumption rooms (Wood et al. 2003).

2.1.3 Philosophy and approach

Since the 1980s new approaches and interventions – low-threshold facilities – for drug users were developed in different countries, in particular with a focus on preventing the spread of HIV and also hepatitis. Drug consumption rooms offer the opportunity to inject drugs without the risk of transmitting BBDs. They are an important harm reduction measure and take into account, that drug users do take drugs and need better opportunities to manage their use and prevent harm. Drug consumption rooms are an important harm reduction measure and are based upon user-centred and confidential approach.

2.1.4 Aims and objectives

Drug consumption rooms have a number of aims: 1) As an important harm reduction measure they aim at reduction of blood-borne virus transmission. 2) Reducing drug-related mortality and opioid-related overdoses is another important objective. Other objectives are 3) to establish contact with difficult-to-reach drug users, and not least the 4) reduction of public nuisance including public injecting, dealing, discarded injection equipment (Dolan et al. 2000). By providing a hygienic and less stressful environment, the users are more likely to be reached with educational messages on harm reduction.

2.1.5 Client groups served and eligibility

Drug consumption rooms are mainly designed for high-risk and marginalised drug users, who otherwise do consume mainly in public places. As this group is especially vulnerable concerning the transmission of BBD, since their consumption environment is often unhygienic, it is important to reach this group of drug users. Low-threshold facilities like consumption rooms can serve as a step into further treatment options. Some drug consumption rooms provide facilities for injecting drug use only, other offer both injecting and smoking possibilities. Female drug users might have special needs, which should be recognised. This might be a separate institution, special opening hours for women, night opening hours, individual approaches etc. (Schu and Tossmann 2005).

2.1.6 Exclusion

Usually consumption rooms do have some exclusion criteria, which differ from country to country and often depend partly on political rules rather than professional reasons. A common measure is to exclude sporadic users and those under-age. Some facilities only offer room for injecting and not for smoking. Other rules might be to exclude those users who are in abstinent or substitution therapy, due to substitution regulations or political requirement. Some facilities exclude those who don’t live in the city or close by, to prevent a magnet effect of the facility and also eliminate overcrowding. Others need the users ID and/or a signed contract to allow access, which might hinder some users to use the services in order not give up their anonymity. These measures can be counterproductive if those users are forced to consume their drugs in public places under non-hygienic conditions. For different reasons, generally users are denied temporary access if they do not follow the house rules.

2.2. Research evidence base – key findings

The evidence for harm reduction measures in general is -compared to especially controlled medical research on treatment – rather scarce, but the intervention may still be effective (Trimbos Institute 2006). Nonetheless, there are a number of studies on the effectiveness of drug consumption rooms. Hedrich identified 15 studies since 2000 (Hedrich 2004). The benefit of drug consumption rooms can be divided into the following areas: health, social policy, regulatory policies, and economic, in each of them a benefit can be drawn (Springer 2003).

2.2.1 Health effects

Concerning health issues there is evidence that consumption rooms do increase the consumers health and stabilise it (Altice et al. 2003). An evaluation of the consumption rooms in Hamburg, Germany, showed that they reached the goal of positive changes in health-related behaviours in the drug users (Zurhold et al. 2003). A nurse-delivered safer injection education in the drug consumption room achieved risk-reduction behaviours in injecting drug users (IDUs) (Wood et al. 2008). The (re-) integration into drug help services does take place (Schu and Tossmann 2005) and general health and social functioning does improve (Dolan et al. 2000). A German study found evidence that drug consumption rooms do reduce the number of drug-related deaths (Poschadel et al. 2002), although the direct impact is difficult to measure, because at the same time drug policy changed as well as an increase in the availability of substitution treatment (Dolan et al. 2000). No overdose-related deaths occurred in drug consumption rooms, as immediate help and first aid is available, although overdose incidents occurs rather often (Dolan et al. 2000). In order to investigate the willingness and acceptance of potential users of a safer injection facility in Vancouver, Canada, a study was conducted before there was such a facility. The following indicators were associated with greater willingness to attend: difficulties in obtaining clean needles, frequent cocaine injection, frequent heroin injection, using a syringe more than once (Wood et al. 2003). Considering the high rates of HIV and hepatitis infection in the studied population, a safer injection facility would be an important measure. Although there exists rather little evidence concerning risk minimisation measures for crack cocaine smokers, there is a need for this target group to offer smoking rooms (Spreyermann and Willen 2003). Concerning consumption rooms with smoking facilities a similar study was conducted on the issue of a safer smoking facility in Vancouver. As sharing and borrowing the pipe can be harmful too, there is a need for such a facility and the willingness to attend is there, especially among those borrowing a pipe, or smoking in rush in public places (Shannon et al. 2006). An evaluation of two Swiss safer smoking facilities showed that there was a great need and often long waiting lists for the inhalant places. No adverse effects like increased violence due to crack cocaine use occurred. On the contrary the users of the smoking room influenced the atmosphere of the whole facility (injecting facility as well) in a positive way (Spreyermann and Willen 2003). Direct influence on the transmission of blood-borne viruses is difficult to obtain and there is no clear evidence that drug consumption rooms do so. But as reduced needle sharing and increased condom use is reported as an effect of consumptions rooms, therefore the risk concerning the transmission of blood-borne viruses are reduced (Dolan et al. 2000).

2.2.2 Reducing public nuisance

One often discussed topic is the acceptance in the neighbourhood and public nuisance or disturbance by drug users using the consumption room facility. A Berlin evaluation found a rather high acceptance of the newly established facility in the neighbourhood (70-80% of randomly assigned residents), being higher among those with higher education and political interest, and lower among those with lower education level and with small children (Schu and Tossmann 2005). Concerns from the neighbourhood of smoking facility did not come true, as there are less people staying and smoking in public places (Spreyermann and Willen 2003). The finding was that the consumption rooms play an important role in reducing public disturbances in the vicinity of open drug scenes (Zurhold et al. 2003). Other research confirms that no public disturbance arises because of the consumption rooms (Freeman et al. 2005; Schu and Tossmann 2005). Australian researchers found no increase of drug use or drug supply offences in the vicinity of the supervised Injection Centre, and loitering in front of the centre declined after opening to baseline level. Similarly no evidence was found for an increase of robbery or theft (Freeman et al. 2005). Several studies found a shift from public drug use to using in consumption rooms, as well as good acceptance among the visitors of the consumption rooms (Dolan et al. 2000). Often the visitors of consumption rooms are poly-drug users (Zurhold et al. 2003; Schu and Tossmann 2005). There is evidence, that these target groups are reached well through the drug consumption facilities (Zurhold et al. 2001; Schu and Tossmann 2005).

2.3 Recommendations

Based on the evidence recommendations for the operating of drug consumption rooms are given.

2.3.1 Location

Drug consumption rooms need to be located near places where the target group is usually staying, so they don’t have to travel a long way to get there (1999). As a low-threshold institution within a comprehensive harm reduction approach, the access needs to be easily available. Drug consumption rooms are particularly necessary in communities with an open drug scene. As lately there is also a growing concern that smoking crack cocaine is a risk of blood-borne transmission (Shannon et al. 2006), facilities should operate for those users who are smoking crack cocaine or heroin as well as injecting.

2.3.2 Programme duration

The visits of drug consumption rooms should not be limited but at all times available to those who need it, as long as they do need it. Therefore no time limitation is needed.

2.3.3 Staffing/Competencies

The staff of drug consumptions rooms should consist of an interdisciplinary team of social workers and medical staff. All staff need to be trained on all issues of drug injecting, including first aid, safer use methods, the effects of different drugs and mix of drugs, the risks associated with injecting (and smoking) drug use. Medical knowledge is essential, as well as social competences are necessary to provide a safe and professional environment. Staff need to be trained in first aid and reanimation, as well as safer use practices, on issues like on effects of mixing different drugs, and prevention of BBD (Schu and Tossmann 2005). They need to have broad knowledge of the help system and cooperate with other institutions, as referring to other services is important.

2.3.4 Treatment environment and holistic treatment and care

Drug consumption rooms should usually be integrated into a drug help system with café, advice and information, medical services and counselling in order to enable the drug users to access different offers of the help system in an integrated setting (Schu and Tossmann 2005). If these services are not available on site, they need to be offered close by. Medical services, e.g. for treating wounds and abscesses, are important to be offered on site. Concerning a holistic treatment drug consumption rooms should raise awareness of safer use practices and offer ongoing advice and information on safer use and harm reduction, as well as referral to other treatment services. Cooperation with other treatment services such as e.g. detoxification and counselling should be part of the service. Female drug users might have special needs, which should be recognised. This might be a separate institution, special opening hours for women, night opening hours, individual approaches etc. (Schu and Tossmann 2005). Evidence shows that also some patients in substitution treatment do use consumption rooms (Schu and Tossmann 2005), therefore it should be considered to keep exclusion criteria low and make it possible for those to use the facility, if they have the strong intent to use, instead of using in the public.

2.3.5 Effectiveness by treatment setting

Treatment settings can differ e.g. referred to the target group – only injecting drug users or smokers as well – or the level of identification needed – ID and signed contract or anonymous admission.

2.3.6 Access

As a low-threshold harm reduction service, drug consumption rooms should provide wide access for those in need, as reaching the main target groups is an important measure in preventing the transmission of BBDs. Mostly consumption rooms have some access limits, e.g. only for people of age, for those, not in substitution, for those living in the city (or area). The Trimbos report points out, that too many limits and exclusions might result in too many users not using the facility but continuing their use in high-risk environments (Trimbos Institute 2006). Concerning the opening hours, it has been shown in one study, that long evening opening hours of drug consumption rooms are widely accessed by the drug users, and also reduce the number of drug users in the neighbourhood (Prinzleve and Martens 2003). To ensure the acceptance of the users and therefore offer effective harm reduction measures, waiting lists should be kept short if possible and only minimal identification requirement should take place. Referral pathways are important services as drug consumption rooms are often the first or only service the users attend, especially with crack cocaine users (Schu and Tossmann 2005). Therefore referrals to other services like detoxification, counselling, motivational interviewing, and substitution treatment can increase the number of drug users in treatment and play an important role in the ongoing treatment system. Nonetheless it seems to be effective to offer as many services as possible in the facility in the sense of integrated care pathways. These services can include food and beverages, the possibility to take showers and do laundry, get second-hand clothes, counselling with different emphases, medical treatment.

2.3.7 Assessment

As part of harm reduction services, comprehensive assessment is not recommended for drug consumption rooms as it may serve as a barrier not to use the service. Nonetheless some basic and brief assessment of the clients situation can be carried out during the first visit, but can also be anonymous.

2.3.8 Management

Drug consumption rooms need to provide not only the possibility to consume drugs, but also advice on harm reduction and safer use messages. The facilities should be client-oriented and have a low-threshold access. The provider of drug consumption rooms has to ensure that the staff is well and up-to-date trained. Referral to other drug help services should be a core element. Apart from the management of the service itself, it is important to involve the neighbourhood, police and other stakeholders in planning a drug consumption room as well as later on (1999). This can be realised in periodic meetings and additional cooperation.

2.3.9 Standards

Working standards for drug consumption rooms should be developed and implemented. These comprise rules for the daily running of the facility, emergency plans and others. Opening hours should adapt the ,users’ needs and might be necessary into the night as well as long hours. The service should be offered continuously without a lot of change (1999).

Drug consumption services do have house rules, which usually contain the following items:

• no drug selling in (and sometimes around) the facility

• no drug use outside the drug consumption room

• no violence

• • no threatening

Medical and hygienic standards are important to ensure the operating of the consumption rooms. There should be a separate room for medical services like attending to abscesses, and also emergencies due to overdoses. For the inhalant use a separate room with good ventilation is essential. Drug users who smoke crack cocaine are usually younger than intravenous drug user and less integrated into any help system. Therefore drug consumption rooms with smoking possibility are an important way to get in touch with this client group (Schu and Tossmann 2005). Waiting rooms should be available inside the facility, and the privacy of the users should be protected (1999). Harm reduction messages should be given permanently, including information on

• risks of blood-borne infections

• risks of abscesses and other damages caused by injecting, and how to avoid them

• information on the dangers of poly-drug use and overdoses

• advice on safer injecting and inhaling practices

• information on other drug treatment services.

2.3.10 Performance and outcome monitoring

The work of drug consumption rooms should be evaluated regularly and adapted if necessary. Outcome Monitoring and data evaluation should follow defined protocols, which must be adequate for the purpose. The documentation should be standardised, but basic enough not to disturb the daily tasks (1999).

3 Testing and vaccination

3.1 Introduction

Most harm reduction interventions specifically aim at the prevention of blood-borne diseases, most particularly HIV and hepatitis infections. Along with needle exchange services and drug consumption rooms testing and vaccination for blood-borne diseases is one of the major harm reduction approaches to reduce the spread of blood-borne infections among the drug use population.

3.1.1 Definition

Testing and vaccination are active interventions which are provided to prevent or manage blood-borne virus infections, mainly viral hepatitis infections (A, B and C) and HIV. Drug users deciding for voluntary testing are usually also offered pre-and post-test counselling. Because of the high transmissibility of hepatitis C virus health policy increasingly pays attention to tackle infections with HCV, an infection that is still most prevalent among injecting drug users.

3.1.2 Context

Injecting drug use and other behavioural risks such as unprotected sex are strongly associated with the high risk of blood-borne virus infections, especially of hepatitis C, hepatitis B and HIV (Drugs in focus 2003; Edlin et al. 2005; Grogan et al. 2005; Castelnuovo et al. 2006; Matic et al. 2008). Due to the spread of HCV infection among drug users hepatitis is a major public health concern (Delile et al. 2006; Wright and Tompkins 2006; Wright and Tompkins 2007). The population of injecting drug users is at particular high-risk as up to 98% of them can be infected with hepatitis C despite a low prevalence of HIV (Shepard et al. 2005; Sy and Jamal 2006; Wright and Tompkins 2006; Reimer et al. 2007). Hepatitis C is transmitted primarily via blood sharing of injecting equipment and is the most common route for infection. In contrast, sexual transmission may occur but is not very usual. If being infected with HCV, alcohol consumption of more than 50g per day is associated with a 60 % increase in the risk of cirrhosis (Castelnuovo et al. 2006). Recent surveys of the prevalence of HIV and AIDS in Europe and Central Asia show that transmission of HIV among IDUs in most Western EU countries is relatively low even though drug injecting continues to contribute to HIV epidemics in many of these countries (EuroHIV 2007; Matic et al. 2008). However, from mid-2004 to the end of 2006 reported HIV cases in the European region rose from 774.000 to 1.025.000, and reported AIDS cases from 285.000 to 328.000 (Matic et al. 2008). Caused mainly by injecting drug use, Eastern Europe and Central Asia have developed to the area with the fastest growing HIV epidemic in the world; HIV incidence there has soared 20-fold in less than a decade (EuroHIV 2007; Matic et al. 2008). In Europe, liver disease is replacing AIDS as one of the most common cause of death among people living with HIV (Matic et al. 2008). In a large cohort of around 5.000 patients who took part in a “EuroSIDA” study, infections with HBV were present in 9 % and infections with HCV in 34 % of the patients living with HIV. The highest prevalence of 48% patients with HCV co-infection was found in Eastern Europe (Matic et al. 2008). In view of transmission rates being still high for HIV and HCV among drug injectors in many European countries, health policy in Europe is focussed on providing effective prevention of hepatitis and HIV/AIDS (EMCDDA 2007). In this respect voluntary testing, related counselling and hepatitis immunisation belong to the health responses to prevent infectious diseases among drug users.

3.1.3 Philosophy and approach

National policies agree that a comprehensive public health approach is vital to reduce the spread of blood-borne diseases among drug users, and thus multi-component prevention services are well established, including voluntary testing for infectious diseases, counselling, vaccination and treatment of infectious diseases. A survey of harm reduction policy and practice in Europe (Trimbos Institute 2006) figured out that in 22 Member States screening on infectious diseases is available to drug users. 20 member States provide prevention, education and treatment of infectious diseases targeting specifically at drug users. Vaccination programmes exist in all European Member States but not all address drug users (Trimbos Institute 2006). With regard to the prevention of hepatitis, some European countries provide vaccination for hepatitis B at the population level, while other countries target at those populations at particular risk. However, the Member States increased efforts to offer easy access to testing, screening, treatment and vaccination of drug-related infectious diseases, and many European countries implemented vaccination campaigns against hepatitis B addressing specifically drug users. In addition, a number of countries have implemented specific programmes aimed at hepatitis C prevention. All European countries offer HIV testing but the availability, accessibility and quality varies considerably in the region (Matic et al. 2008). Highly active antiretroviral treatment (HAART), available in Western Europe since 1996, is reported to be widely available in European countries; the WHO estimates the coverage of HAART in Europe at least to be 75% (EMCDDA 2007). To improve availability, accessibility and quality of testing, counselling and treatment Matic, Lazarus et al. (2008) recommend to transform national responses “from an episodic, one-time approach to a strategic long-term national commitment based on evidence and human rights approaches, national needs and opportunities”.

3.1.4 Location

There are many generic and specific services that are suitable locations for providing testing for blood-borne diseases such as hepatitis B and C, and HIV, pre-and post-test counselling and vaccination. Counselling, testing and vaccination for drug users can be successfully integrated in health care setting such as

• primary care, maternity services, and emergency departments, • opioid substitution treatment (OST) and other drug treatment programmes,

• infections disease clinics, health departments and anonymous HIV screening centres, and in

• criminal justice systems.

3.1.5 Aims of the intervention

Main aim of testing and vaccination is to prevent blood-borne diseases resulting from risk behaviours, and in case of infected clients to provide comprehensive healthcare and treatment (National Treatment Agency 2002). Drug treatment and healthcare services have to provide access to testing for hepatitis B and C and HIV, and for hepatitis immunisation. In this respect vaccination programmes targeting at drug users have to be offered, either by their own service or by transferral to an appropriate service. In addition services should provide pre-and post-test counselling to all drug using clients with the aim to enable them to avoid BBV infections and develop a healthier lifestyle. Testing and vaccination also include risk assessments and information to drug users on the transmission of hepatitis B and C and HIV. Drug users should be given advices on how to prevent harmful behaviour. Clients requiring treatment for blood-borne infections or other health problems must be referred to treatment where it is appropriate.

3.1.6 Client group served

Testing for blood-borne diseases and vaccination is targeting at all problem drug users that may practice sharing of injecting equipment or unsafe sex. In view of the high proportion of injecting drug users being infected with hepatitis C, HIV and also with hepatitis B (Hahn et al. 2001; Stevenson et al. 2001; Drugs in focus 2003; Gerlich et al. 2006; Wright and Tompkins 2007) it is essential to offer pro-active testing and screening for drug-related infectious diseases to high risk groups (Trimbos Institute 2006). In general, vaccination for hepatitis B should be made available for all problem drug users.

Apart from drug user at risk a further specific target groups for testing, vaccination and related counselling. Specific target groups are

• Drug users infected with HCV

• New and young injectors

• Prisoners

• Hidden populations at risk such as drug addicted sex workers, migrants etc.

The hepatitis C virus is highly infectious and spreads rapidly among drug users with direct contact with infected blood such as in case of sharing injection equipment. As drug users with hepatitis C have been found to be at further risk of infection with hepatitis B (National Treatment Agency 2002), testing and vaccination for HBV should be offered to drug users already infected with hepatitis C and not been protected by hepatitis B vaccine. In research there is evidence that new and young injecting drug users (below age 25) are at high risk of becoming infected with hepatitis C and HIV (Barrio et al. 2007; EMCDDA 2007). A Scottish study investigated the outbreak of acute hepatitis B infection among injecting drug users between 1997 and 1999. The results show that 12% of the hepatitis B cases were found in the young and inexperienced group of drug injectors aged 16-19 years old (Stevenson et al. 2001). In young injectors infections are likely to be recently acquired, and thus screening for blood-borne diseases needs to cover those groups who are known to be at particular high risk of HCV and HIV infection. A further priority group are prisoners, and in particular women prisoners (DiCenso et al. 2003; Macalino et al. 2005) and young offenders (Drugs in focus 2003). Research indicates that imprisonment is an independent risk factor for the transmission of hepatitis and HIV. Rates of HIV and hepatitis C infection among prison inmates are in most European countries much higher than those in the general population (e.g. Champion et al. 2004; Macalino et al. 2004). As problem drug users, sex workers and migrants are often difficult to reach by general health care services, testing and hepatitis B vaccination programmes specifically for hard to reach risks groups and for hidden populations at risk are recommended. Young injectors most often do not access traditional drug counselling services or drop in centres, therefore new strategies to approach this group most at risk have to be developed.

3.1.7 Exclusion

In general, all drug users at risk for blood-borne diseases should be provided with testing and immunisation. The topic of exclusion is discussed controversial with respect to the treatment of hepatitis C infection. Even though treatment for hepatitis C infection has improved considerably, illicit drug users were considered ineligible for HCV treatment until recently (Drugs in focus 2003; Haydon et al. 2005). Despite the fact that users of illicit drugs are the primary risk group for HCV transmission, treatment guidelines have explicitly excluded active illicit drug users from consideration for HCV treatment until a few years ago. The main reasons for excluding drug users from HCV treatment were that drug users were regarded as to be too unstable to comply with the requirements of the HCV treatment regimen because of their potential disposition for psychiatric side-effects, and the risk of HCV re-infection (Haydon et al. 2005; Fischer et al. 2006).

If not treated, infection with hepatitis C virus becomes chronic in the majority of individuals (Haydon et al. 2005). In research, HCV treatment for users of illicit drugs has shown to be feasible and effective if delivered appropriately, which is for instance after successful detoxification or during maintenance treatment with methadone. Evidence suggests that risks of HCV treatment can be managed effectively by interdisciplinary teams involving hepatologists, drug counsellors, and mental health professionals (Haydon et al. 2005). Not all drug users may want or need antiviral therapy, but none should be excluded from HCV treatment solely on basis of their drug addiction (Edlin et al. 2005; Trimbos Institute 2006). To reduce the rate of hepatitis C infections is a major health concern which requires more effective prevention (e.g. needle exchange services) but also the provision of appropriate HCV treatment to former or current drug users.

3.2 Research evidence base – key findings

Evidence on effectiveness of testing and vaccination is presented separately for the different interventions. As drug users who are infected with hepatitis C and/or HIV might be in need for medical treatment evidence for treatment is also summarised.

3.2.1 Testing and related counselling

Research does not present a clear picture as regards evidence for testing and pre-and post-test counselling. Study results suggest that testing for blood-borne diseases might be effective in reducing HIV infections in terms of a reduced risk behaviour as a consequence of testing and counselling. In addition testing and counselling may increase drug users enrolment in medical or drug treatment (Trimbos Institute 2006; Samet et al. 2007). A retrospective cross-sectional survey of clients attending 21 specialist addiction treatment clinics in greater Dublin came to the conclusion that the proportion of clients screened for HCV, HBV and HIV infection has increased since the introduction of a screening protocol in 1998 (Grogan et al. 2005). At the same time targeted vaccination for opiate users against hepatitis B became more successful in Ireland. However, despite increasing availability of harm reduction intervention, prevalence and incidence remained high among opiate users in treatment. In the Dublin sample prevalence for hepatitis C was 66 % and for HIV 11 %. A review on HIV epidemic in Western Europe indicates that in the 1990s large-scale voluntary HIV testing of pregnant women followed by antiretroviral treatment of those found to be seropositive has substantially dropped the number of HIV-infected newborn babies (Hamers and Downs 2004). A more recent survey on HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment found that HIV testing remained steady in Western Europe in the period from 2001 to 2005, while the number of HIV tests performed in some Central and Eastern European countries rose significantly during the same period (Matic et al. 2008). Based on research there is no clear evidence for the effectiveness of testing for blood-borne diseases and counselling as single interventions. Amundsen (2006) recently noted that HIV testing and counselling for injecting drug users is often combined with other prevention measures such as needle exchange programmes, treatment etc. For this reason it is difficult to identify which prevention measures contributed most to the reduction in HIV seroprevalence. In a former study conducted among intravenous drug users in the three Scandinavian countries effectiveness of needle exchange programmes had been compared with effectiveness of HIV counselling and testing (Amundsen et al. 2003). Due to the lack of control groups or analysis of confounders the author concluded that it is simply unknown which factors are more important for reducing HIV-transmission, HIV testing and counselling or for instance needle exchange programmes (Amundsen 2006). Apart from the question of effectiveness research highlights the problem of consequences of unknown infection status. Current and former injecting drug users not being in contact with services will be unaware that they may have hepatitis C and/or HIV. Infection with both HCV and HIV reduces the chance to recover from acute hepatitis C virus and accelerates the progression of HCV infection to cirrhosis (Matic et al. 2008). The authors underlined that in Europe the prevalence of HCV infection in HIV-infected patients is particularly high and still rising, with about 80–90 % of cases occurring among injecting drug users. A recent study from England and Wales evaluated the cost-effectiveness of testing for hepatitis C virus among former injecting drug users (Castelnuovo et al. 2006). According to the results case finding for hepatitis C in injecting drug users is cost effective in general, and most cost-effective if targeted at populations whose HCV disease is probably more advanced.

3.2.2 Vaccination against hepatitis

Hepatitis B vaccines have been licensed since 1982, and hepatitis A vaccines since 1992. In 1996, a combined hepatitis A and B vaccine became available. No vaccine is currently available to protect against hepatitis C infection. Vaccination programmes play an important role in the prevention of hepatitis A and B. As in Europe the proportion of IDUs being infected with hepatitis B appears to have been declined, the reduction seems to reflect increasing impact of vaccination (EMCDDA 2007a). Even though national hepatitis B vaccination programmes seem to be an effective intervention in reducing HBV infection, many European countries do not have national vaccination programmes at population level. Research shows that vaccination against viral hepatitis B is effective in preventing hepatitis B infection after completing the primary course of 3 vaccinations. The vaccine is recommended for people at high risk for infection as immunisation protects against chronic carriage of viral hepatitis B. Recent evidence which is based on a large number of follow-up studies indicates that immune memory exhibits long-term persistence, despite of antibody decline or loss (Van Damme and Van Herck 2007). All adequately vaccinated individuals have shown evidence of immunity that protects against infections for up to 15 years. However, follow-up studies with up to 12 years observation, as well as studies employing mathematical models suggest that after primary vaccination antibodies will persist for at least 25 years (Van Damme and Van Herck 2007). Vaccination against hepatitis B seems to have also a positive influence on the hepatitis C serostatus. A comparative cohort study in 16 public centres for drug users in northeastern Italy found that being HBV seropositive was strongly associated with being HCV seropositive (Quaglio et al. 2003). Heroin users who had been vaccinated for hepatitis B were not significantly more likely to be HCV seropositive than heroin users who were HBV seronegative. A study from the US (Edlin et al. 2005) supported the conclusion that vaccination for hepatitis B is important component of hepatitis C care because vaccination may improve a reduction in HCV risk behaviour. However, a comparative cohort study from Switzerland among patients entering heroin-assisted treatment in three different periods (2000-2002, 1998 and in 1994-1996) stated that the significant reduction of HBV and HAV infections found in patients entering treatment between 2000 and 2002 was not related to vaccination (Gerlich et al. 2006). The decrease in hepatitis A and B infections was attributed to less sharing of injection equipment and more hygienic environments of injecting drug users in the last 10 years. Two prospective studies from the United States highlight that only a certain proportion of drug users found to be eligible for HBV vaccination completed all three doses of vaccination. In the street-recruited sample of drug users from New York City 41 % completed all three doses (Ompad et al. 2004), and in the study among IDUs from New Haven 66 % completed three vaccinations (Altice et al. 2005). Both studies found that correlates for vaccine acceptance include older age. In addition the New Haven study reveals that daily injecting, being homeless and links to a syringe exchange programme is associated with completing the all three vaccinations for hepatitis B.

3.2.3 HIV treatment

The introduction of Highly Active Antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in 1996 in Western Europe turned a mortal disease into a manageable chronic infection. Nowadays HAART bases on a combination of three or four substances. Antiretroviral therapy is an effective treatment for HIV infections that has resulted in considerable declines in HIV-related morbidity and mortality (Hamers and Downs 2004; Matic et al. 2008). The decrease in mortality is found across all risk groups, but to a lower proportion among injecting drug users (Altice et al. 2003). Reductions in mortality depend much from accessibility and affordability of HAART. In the European regions HAART coverage increased from 282.000 people in 2004 to

435.000 in 2007, and coverage was estimated as higher than 75 % in 38 European countries (Matic et al. 2008). However, the authors emphasised that there are still shortcomings. In Central and Eastern Europe, where the need for HAART is very high coverage is still too low. In addition, IDUs continue to have no equal access and adherence to antriretroviral therapy for HIV (Samet et al. 2007; Matic et al. 2008; Wood and Montaner 2008). In Canada where antiretroviral therapy is offered free of charge though general health care services it has been shown that that one-third of HIV-related deaths occurred among individuals who had never accessed antiretroviral therapy (Wood and Montaner 2008). Furthermore research pointed out that drug injectors have lower levels of adherence to HIV treatment due to compulsive drug use, psychiatric illness and poor living conditions such as homelessness. On the other hand studies indicate that many IDUs can manage high adherence to antiretroviral therapy and HIV-therapy (Gölz 1999; Wood and Montaner 2008), and that patients support may improve adherence. Research findings show that due to side effects about 25% of patients stop therapy within the first year of HIV treatment and the same number of patients does not take the recommended dosages of their medication (Hoffmann et al. 2007). To optimise HIV treatment for drug addicts it is recommended to offer HIV testing with referral to substance use treatment that is linked to or integrated into HIV treatment (Altice et al. 2003).

3.2.4 Treatment of hepatitis B and C