14 Drug treatment for clients with co-occuring disorders (COD)

| Reports - Models of Good Practice in Drug Treatment |

Drug Abuse

14 Drug treatment for clients with co-occuring disorders (COD)

Guidelines for treatment improvement

Moretreat-project

CIAR Hamburg Germany

October 2008

The content of this report does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the European Commission. Neither the Commission nor anyone acting on its behalf shall be liable for any use made of the information in this publication.

Content

1 Introduction

1.1 Definition

1.2 Context

1.3 Relevance of the problem

1.4 Philosophy and treatment approaches

2 Research evidence base – key findings

2.1 Evidence based interventions

2.2 Evidence for different treatment models

3 Recommendations

3.1 Guidelines for core elements of interventions

3.2 Guidelines for interventions and programme elements

References

1 Introduction

The relationship between substance use and mental disorders dates to the late 1970s, when practitioners increasingly became aware of the implications that two parallel disorders imply for treatment outcomes.

1.1 Definition

Co-occurring disorders (COD) refer to occurrence of both substance use (abuse or dependence) and mental disorders. The term „co-occurring disorders“ replaces other terms such as „dual disorder”, „dual diagnosis“ or “psychiatric co-morbidity”. A diagnosis of co-occurring disorders is confirmed when at least one disorder of each type has established independently of the other and is not simply a cluster of symptoms resulting from the one disorder. In the context of substance use clients with cooccurring disorders have one or more disorders relating to the misuse of alcohol and/or other drugs as well as one or more mental disorders.

1.2 Context

The nature of the relationships between mental disorders and substance misuse are complex as the latter can occur at any phase of mental illness and can be caused by a number of factors such as self-medication, genetic vulnerability etc. The identification of the primary diagnosis may be problematic due to the mimicking effect of symptoms linked to mental illness and those linked to intoxication and withdrawal of substance use. For this reason the identification of a disorder requires to apply a particular classification system (Wittchen et al. 1996) such as Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) IV or International Classification for Diseases (ICD) 10.

1.3 Relevance of the problem

The co-occurrence of a severe mental illness and a substance abuse or dependence disorder is prevalent enough to be considered a rule rather than an exception. For instance, in the UK the overall prevalence of substance use disorder in mental health patients was 36.3 % (Menezes et al. 1996). Smaller clinical and treatment studies have indicated that at least one half of the patients in psychiatric and substance use treatment have been diagnosed with both co-morbid psychiatric and substance use disorders (Callaly et al. 2001, Krausz et al 1999). In more recent studies consistently comparable results were found. Havassy et al. (2004) found high prevalence rates of severe mental illness in drug treatment clients and also a high prevalence of serious drug problems in mental health patients. Schäfer & Najavits (2007) showed that in clinical populations 25-50% have a lifetime COD of posttraumatic stress disorder and substance use disorder.

The association between depression and substance abuse was particularly striking and became the subject of several early studies in the United States (e.g. Woody and Blaine 1979; De Leon 1989; Pepper et al. 1981; Rounsaville et al. 1982b; Sciacca 1991). Studies conducted in substance abuse programs typically reported that 50-75 % of clients had some type of co-occurring mental disorder (although not usually a severe mental disorder) while studies in mental health settings reported that between 20 and 50 percent of their clients had a co-occurring substance use disorder (Kessler et al. 1996; Sacks et al. 1997, Compton et al. 2000). The study of Rodriguez-Jimenez et al. (2008) revealed that schizophrenic patients exhibit a high lifetime prevalence (40-50%) of comorbid substance use disorders. A number of studies found strong associations between substance use disorders and antisocial personality disorder. Oyefeso et al. (1998) found that the prevalence rate of personality disorder among drug-dependent inpatients was 86 %. The mentioned studies vary in their settings, sample sizes, methods and criteria for determining a disorder which can result in different estimates. However, despite these differences the reported rates of COD are consistent across all studies.

1.4 Philosophy and treatment approaches

Clients with co-occurring disorders often show poor medication compliance, physical co-morbidities, poor health, and poor self-care. They also have poorer outcomes such as higher rates of relapse, hospitalisation, depression, and suicide risk (Drake et al. 1998b; Schäfer & Najavits, 2007). According to Coffey and colleagues, hospitalisation for clients with both a mental and substance use disorder was more than 20 times higher than for substance abuse only clients and five times higher than for mental disorder only clients (Coffey et al. 2001). Studies in the United States found that individuals with substance abuse disorder and COD seek treatment more frequently than those with one disorder (Narrow et al. 1993). On the other hand those clients with three or more disorders have never received any treatment (Kessler et al. 1996). Problems in the provision of health care led to new treatment models and strategies in the United States (Anderson 1997; De Leon 1996; Miller 1994a; Minkoff 1989; National Advisory Council [NAC] 1997; Onken et al. 1997; Osher and Drake 1996). The increased interest in providing effective treatment for COD clients is reflected by new patient placement criteria the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM 2001) had put into practice. To increase treatment effectiveness the National Association of Mental Health Program in the US emphasised the importance to know about both mental health and substance abuse treatment when working with COD clients. In addition a classification of treatment settings has been provided to facilitate systematic treatment planning, consultations, collaborations, and integration. However, in the last decade, dissemination of knowledge has been widespread. Numerous books and hundreds of articles have been published, from counselling manuals and instruction (Evans and Sullivan 2001; Pepper and Massaro 1995, Coffey et al. 2001). In spite of these developments individuals with substance use and mental disorders commonly appear at facilities that are not prepared to treat them. They may be treated for one disorder without consideration of the other disorder, often shifting from one type of treatment to another as symptoms of one disorder or another become predominant.

2 Research evidence base – key findings

Even though available literature provides information on treatment approaches to respond to clients with co-occurring disorders, in Europe there is only limited evidence on effective treatment interventions for this population. In addition there is little information about the most effective models of treatment delivery. The majority of research on co-occurring disorders has been conducted in the USA, and especially in North America. Due to very different health and social care systems in the United States and Europe evidence generated by US studies can not be simply translated into the European situation. Currently a number of research studies on co-morbidity have been undertaken in Europe which are of value for practice. However until these research findings are peer-reviewed and published the implementation of evidence-based interventions remains difficult. Evidence from Northern American studies indicates that an existing mental disorder often makes effective treatment for substance use more difficult (Mueser et al. 2000; National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors and National Association of State Alcohol and Drug Abuse Directors 1999). Evidence suggests that outpatient drug treatment can lead to positive outcomes for clients with less serious mental disorders, even if treatment is not tailored specifically to their needs. This conclusion is supported by the results of the comprehensive database “DATOS” on substance abuse treatment (Flynn et al. 1997). Clients who attended outpatient drug treatment for a period of three months reported lower rates of drug use compared to their rate of use prior to treatment (Hubbard et al. 1997; Simpson et al. 1997a).

2.1 Evidence based interventions

On basis of research findings there are a number of interventions which have been identified as currently demonstrating evidence for treatment of co-occurring disorders. These practices are:

• Pharmacological treatment

• Psychosocial interventions

• Contingency management

• Case management / intensive case management

• Family intervention

• Assertive community treatment

This list is not complete and future research may find evidence for further interventions. However, some further approaches will also be presented below.

Pharmacological interventions

Pharmacological proceedings over the past decade have produced antipsychotic, antidepressant, anticonvulsant, and other medications with greater effectiveness and fewer side effects. Due to better medication regimens many people who once would have been too unstable for medical treatment or who had shown a poor prognosis now are enabled to develop more functional lives. Reviews identified a majority of studies suggesting the effectiveness of second-generation antipsychotics, particularly clozapine, for patients with schizophrenia and a co-morbid substance use disorder. (SAMHSA 2005) Substance abuse treatment programmes increasingly appreciate the importance of providing medication to control drug abuse symptoms as an essential part of treatment. To ensure that proper medication is prescribed when needed it is important to assess and describe the clients’ behaviour and symptoms. Support from mutual self-help groups may be a powerful resource for clients to learn about the effects of medication and to accept medication as part of recovery.

Psychosocial interventions

Since identification of the problem of co-occurring severe mental illness and substance use disorder in the early 1980s, psychosocial interventions have steadily been developed and tested. In the following years there were many pre-post studies but still only a few controlled trials (Drake et al. 1998). In recent years numerous controlled trials have been undertaken, most often in Northern America. Treatment approaches are emerging with demonstrated effectiveness in achieving positive outcomes for clients with COD. These promising treatment approaches base upon comprehensive integrated treatment and provide a variety of interventions for clients with COD; substance abuse treatment includes interventions such as contingency management, cognitive-behavioural therapy, relapse prevention, and motivational interviewing. In fact, it is now possible to identify “guiding principles” and “fundamental elements” for COD treatment in COD settings which have been proven effective for the COD population with serious mental illness.

Individual counselling

Studies of individual counselling are largely based on the technique of motivational interviewing (Miller & Rollnick 2002) and most often focused on substance use outcomes. Three studies assessed the impact of a single session (Baker et al. 2002a, 2002b; Hulse & Tait 2002; Swanson, Pantalon, & Cohen 1999) while four studies examined several individual counselling sessions (Graeber et al. 2003; Baker et al. 2006; Edwards et al. 2006; Kavanagh et al. 2004). Findings on substance use, mental health, and other outcomes including treatment attendance were inconsistent. Graeber, et al. (2003) found remarkable positive results on substance use outcomes following three sessions of motivational interviewing but three other studies on several sessions (3–12) of motivational interviewing and/or cognitive-behavioural counselling found no differences in substance use outcomes (Baker et al. 2006; Edwards et al. 2006; Kavanagh et al. 2004). In the long-term study of Barrowclough et al. (2001) which included 9 months of motivational interviewing and cognitive-behavioural treatment some positive results were found at 9, 12, and 18 months, but most of the differences in substance use and other outcomes were not sustained at 18 months (Haddock et al. 2003). Thus, the evidence for individual counselling based on motivational interviewing and/or cognitive-behavioural counselling is relatively weak and inconsistent.

Group counselling

Group counselling interventions are usually delivered once or twice a week over a period of 6 months or longer. They are most often based upon cognitive-behavioural techniques, education, peer support, and focussed on managing mental and substance use disorders. There are eight studies on group counselling taken into consideration of which half are experiments and half are quasi-experimental. The results of these studies are considerably consistent in demonstrating that group counselling has positive effects on substance use and on other symptoms than mental illness. Bellack et al. (2006) found positive outcomes of a multi-intervention approach (including cognitive-behavioural interventions, skills training and contingency management) for clients with schizophrenia and drug use disorders, although overall attrition was high. Similarly, Weiss et al. (2000, 2007) showed that cognitive-behavioural intervention has positive substance use outcomes for clients with bipolar disorder plus substance use disorder.

Contingency management (CM)

A substantial empirical database supports effectiveness of CM techniques in enhancing treatment retention and confronting drug use (e.g. Higgins 1999; Petry et al. 2000). The techniques have been shown to address the use of a variety of substances such as opioids (e.g. Higgins et al. 1986; Magura et al. 1998), marijuana (Budney et al. 1991), alcohol (e.g. Petry et al. 2000), and cocaine (Budney and Higgins 1998). CM has been studied among populations of homeless persons, many with COD (Milby et al. 1996; Schumacher et al. 1995). Results show that participants in treatment with contingencies were more likely than those in conventional treatment to be abstinent from drugs, to move into stable housing, and to gain regular employment following treatment. CM principles and methods can be applied flexible to cope with new situations and can increase treatment effectiveness. It should be noted that many programmes make use of CM principles informally when they reward particular behaviours. CM techniques have not been implemented in community-based settings until recently. The use of vouchers and other reinforcers has achieved empirical support (e.g. Higgins 1999; Silverman et al. 2001) even though there is little evidence for the efficacy of different reinforcers. The effectiveness of CM principles when applied in community-based treatment settings and specifically with clients who have COD remains to be demonstrated.

Case management / Intensive case management (ICM)

Case management refers to intensive, team-based, multidisciplinary, outreach-oriented and coordinated services, usually involving assertive community treatment (Stein & Test, 1980) or a close variant called intensive case management. All studies of case management interventions, half experiments and half quasi-experiments, incorporated some forms of integrated treatment for co-occurring substance use disorders. These studies produced inconsistent results on substance use outcomes as well as on mental illness symptoms. Six of the studies reported some reductions in substance use, and further studies found effectiveness in other areas such as increasing engagement, increasing community tenure, and improving quality of life. Traditional outcomes of case management, such as increasing community tenure, are consistently obtained with dual diagnosis clients. ICM has shown to be effective in engaging and retaining clients with COD in outpatient services and to reduce rates of hospitalisation (Morse et al. 1992). Treatment combining substance abuse counselling with intensive case management has been found to reduce substance use behaviours for this population in terms of days of drug use, remission from alcohol use, and reduced consequences of substance use (Bartels et al. 1995; Drake et al. 1993, 1997; Godley et al. 1994). The continued use and further development of ICM for COD is indicated based on its overall utility and modest empirical base.

Family intervention

Only one study could be identified that included family psycho-education as a consistent intervention. Barrowclough et al. (2001) combined family intervention with individual counselling. The results were positive for substance use and other outcomes at various follow-ups, but mostly faded when the intervention ended. In conclusion family intervention for persons with co-occurring disorders has not yet been evaluated sufficiently.

Assertive community treatment (ACT)

The ACT model has been researched widely as a programme designed for people who are chronically mentally ill. Randomised trials comparing clients with COD assigned to ACT programmes with similar clients assigned to standard case management have demonstrated better outcomes for ACT. It has been shown that the ACT model is effective for mental disorders in reducing re-hospitalisation, improvement of alcohol and substance abuse, lower 3-year post-treatment relapse rates for substance use, and improvements of quality of life (Drake et al. 1998a; Morse et al. 1997; Wingerson and Ries 1999). ACT has not been effective in reducing substance use when the substance use services were not provided directly by the ACT team (Morse et al. 1997). Research also reveals that ACT is more cost-effective than case management (Wolff et al. 1997). Other studies of ACT were less consistent in demonstrating higher effectiveness of ACT compared to other interventions (e.g. Lehman et al. 1998). In addition, the study of Drake et al. (1998b) did not show improvement on several measures important for establishing the effectiveness of ACT with COD; that is retention in treatment, self-reported substance abuse and stable housing. Drake noted that elements of ACT were incorporated gradually into the standard case management which made it difficult to determine the effectiveness of ACT. Further analyses indicated that clients in high-fidelity ACT programmes showed greater reductions in alcohol and drug use and attained higher rates of remissions in substance use disorders than clients in low-fidelity programmes (McHugo et al. 1999). Based on predominately American results ACT is an effective treatment model for clients with COD, especially those with serious mental disorders.

Residential treatment

Nearly all studies on residential treatment compared a more integrated approach to residential treatment with a less integrated approach. Some of the residential programmes were short-term (6 months or less) and some long-term (1 year or more). The long-term studies did consistently find positive outcomes related to substance use. Brunette et al. (2001) showed that long-term residential treatment was more sustainable effective than short-term residential treatment as regards substance use outcomes. The long-term studies also consistently demonstrated positive effects on other outcomes. A number of large-scale, longitudinal, national, multi-site treatment studies have proven the effectiveness of residential substance abuse treatment (Fletcher et al. 1997; Hubbard et al. 1989). In general, these studies have shown that residential substance abuse treatment results in significant reduction of drug use and crime, and in increased employment. The most recent national study is the American DATOS study (Fletcher et al. 1997) which involved a total of 10,010 adult clients admitted to short-term inpatient substance abuse treatment, residential TCs, outpatient drug-free programmes, or outpatient methadone maintenance programmes across 11 cities in the US. Of the 4,229 clients eligible for follow-up and 2,966 were re-interviewed after treatment (Hubbard et al. 1997). Among these clients there was a high prevalence of clients with COD. The DATOS study participants displayed positive outcomes for substance use and other maladaptive behaviours in the first year after treatment. Substance abusers who at least remain in treatment for 3 months have more favorable outcomes than those dropping out earlier (Condelli and Hubbard 1994; Simpson et al. 1997b, 1999; Knight et al. 2000). Broome and colleagues (1999) found that hostility was related to a lower likelihood of staying in residential treatment beyond the 90-day threshold, but depression was associated with a greater likelihood of retention beyond the threshold.

2.2 Evidence for different treatment models

In research there is a discussion about the most effective models of treatment and care for people with co-occurring disorders. There are three main models which can be differentiated even though they might exist across different treatment settings such as outpatient treatment, inpatient and residential treatment.

• Serial treatment models are based upon a consecutive treatment of psychiatric and substance use disorders. Patients attend separate treatment for mental health and substance use disorders with little communication between substance use services and psychiatric services. It is argued that such separate treatment services are not appropriate to meet the needs of patients with co-occurring disorders.

• Parallel treatment models deliver substance misuse and mental health services by establishing a liaison to provide the two services concurrently. Specific liaisons are to facilitate assessment and referral between psychiatry and substance use services. However, in practice it may happen that substance misuse and mental health services operate referral criteria that specifically exclude patients with co-occurring disorders, particularly as regards residential rehabilitation.

• Integrated treatment models include treatment for the mental illness and substance use by delivering both pharmacologic and psychosocial interventions. Experience for integrated treatment emerges from the USA and research suggests that treatment and management of co-occurring disorders is most successful through an integration of both types of treatment. Evidence also suggests that clinical teams must provide a treatment approach incorporates assertive community treatment, motivational and behavioural interventions, relapse prevention, pharmacotherapy and social approaches.

Integrated treatment

During the last decade, integrated treatment has continued to evolve, and several models have been described (Drake and Mueser 1996b; Lehman and Dixon 1995; Minkoff and Drake 1991; Solomon et al. 1993). A recent survey in the USA found that only 12 % of clients with COD mental health and substance use problems received interventions for both (Epstein et al., 2004). Thus, current intervention research on co-occurring disorders assumed the need to integrate mental health and substance abuse services at the clinical level (McHugo et al., 2006). In a review of mental health center-based research for clients with serious and persistent mental illness, Drake and colleagues (1998b) concluded that comprehensive, integrated treatment, “especially when delivered for 18 months or longer, resulted in significant reductions of substance abuse and, in some cases, in substantial rates of remission, as well as reductions in hospital use and/or improvements in other outcomes”. Mangrum et al. (2006) examined 1-year treatment outcomes of 216 individuals with co-occurring severe and persistent mental illness and substance use disorders who were assigned to an integrated or parallel treatment condition. Comparisons indicated that the integrated group achieved greater reductions in the incidence of psychiatric hospitalisation. Several studies which focussed on substance abuse treatment addressing COD have demonstrated better treatment retention and outcome when mental health services were integrated onsite (Charney et al. 2001; McLellan et al. 1993; Saxon and Calsyn 1995; Weisner et al. 2001). On the other hand a prospective study among substance-abusing schizophrenic patients found no statistical significance between integrated and non-integrated treatment programmes as regards the mental state outcomes (Hellerstein 1995). However, research on integrated treatment expands in the US as previous reviews have documented modestly superior outcomes (Brunette et al., 2004; Drake et al., 2004; Mueser et al., 2005). However, there is no clear evidence that adoption of an integrated treatment model by European health services will be effective as well. Research has demonstrated that nonintegrated substance abuse treatment programmes can also be beneficial for clients with co-occurring substance use disorders and mental illness -even in case of serious mental symptoms (e.g. Karageorge 2001). Many clients in traditional substance abuse treatment settings who had mild to moderate mental disorders were found to do well with traditional substance abuse treatment methods (Hser et al. 2001; Hubbard et al. 1989; Joe et al. 1995; Simpson et al. 2002; Woody et al. 1991).

Continuity of care

Evidence for the benefits of ensuring continuity of care mainly comes from sources of the United States. A study among criminal justice populations not specifically identified as having COD found that 3 years after completing prison treatment and additional aftercare only 27 % of these offenders returned to prison (Wexler et al. 1999). In contrast, about three-fourths of those not completing both programmes were re-imprisoned. Similar findings have been reported by Knight et al. (1999). A study of homeless clients with COD provided further evidence that aftercare is crucial for positive treatment outcomes (Sacks et al. 2003). Clients who lived in supported housing after leaving a therapeutic community demonstrated a reduction in antisocial behaviour and an increase in social behaviour. Burnam (1995) undertook an experimental evaluation of residential and non-residential treatment for homeless adults with substance abuse disorder and COD in Los Angeles, California. The study found a significant difference between the two groups in favour of residential treatment but no clear difference in substance use at nine months.

3 Recommendations

3.1 Guidelines for core elements of interventions

The following guidelines derive from proven models, clinical experience, and the growing empirical evidence (see part 2). It suggests that the provider needs to address in concrete terms the challenges of providing access, assessment, appropriate level of care, integrated treatment, comprehensive services, and continuity of care for clients with COD. This first section provides guidance that is relevant to design processes that are appropriate for this population within each of these key areas18 .

Providing access

A “no wrong door” policy should be implemented for the full range of clients with COD. “Access” refers to the process of initial contact with the service system and occurs in the following main ways:

• Routine access for individuals seeking services who are not in crisis

• Crisis access for individuals requiring immediate services due to an emergency

• Outreach, in which agencies target individuals in great need (e.g. people who are homeless) who are not seeking services or cannot access ordinary routine or crisis services

• • Access that is involuntary, coerced, or mandated by the criminal justice system, employers, or the child welfare system.

Completing a full assessment

The challenge of assessment for individuals with COD in any system involves maximising the likelihood of the identification of COD, immediately facilitating accurate treatment planning, and revising treatment over time as the client’s needs change.

The following levels of assessment should be implemented:

• Screening

Screening is a formal process of testing to determine whether a client does or does not warrant further attention at the current time in regard to a particular disorder and, in this context, the possibility of a co-occurring substance use or mental disorder. Screening processes (conducted by counsellors using their basic counselling skills) always should define a protocol for determining which clients screen positive and for ensuring that those clients receive a thorough assessment.

• Basic assessment

Information gathered in this way is needed to ensure that the client is placed in the most appropriate treatment setting (as discussed in the next parts) and assisted in providing mental disorder care that addresses each disorder. A basic assessment consists of gathering information that will provide evidence of COD and mental and substance use disorder diagnoses; assess problem areas, disabilities, and strengths; assess readiness for change; and gather data to guide decisions regarding the necessary level of care. In the assessment process (from engagement, screening for and detect COD, diagnosis and level of care to treatment plan) the counsellor should seek to accomplish the following aims:

• To obtain a more detailed chronological history of past mental symptoms, diagnosis, treatment, and impairment, particularly before the onset of substance abuse, and during periods of extended abstinence.

• To obtain a more detailed description of current strengths, supports, limitations, skill deficits, and cultural barriers related to following the recommended treatment regimen for any disorder or problem.

• To determine stage of change for each problem, and identify external contingencies that might help to promote treatment adherence.

A major goal of the screening and assessment process is to ensure the client is matched with appropriate treatment (see below).

Adopting a multi-problem, tailored and phased approached viewpoint As people with COD generally have an array of mental health, medical, substance abuse, family, and social problems treatment should address immediate and long-term needs for housing, work, health care, and a supportive network services should be able to integrate care to meet the multidimensional problems. As co-occurring disorders arise in a context of personal and social problems, with a corresponding disruption of personal and social life, approaches are important that address specific life problems early in treatment. These approaches may incorporate case management to help clients find housing or handle legal and family matters. Services for clients with more serious mental disorders, must be tailored to individual needs and functioning (CSAT 1998). The manner in which interventions are presented must be compatible with client actual needs and functioning. Such impairments frequently call for relatively short, highly structured treatment sessions that are focused on practical life problems. Careful assessment of such impairments and a treatment plan consistent with the assessment are therefore essential. Clients are progressing empirically though three to five identified phases (Drake and Mueser 1996; Sacks et al. 1998) or stages including engagement, stabilisation, treatment, and aftercare or continuing care. The use of these phases enables the clinician/practitioner (whether within the substance abuse treatment or mental health services system) to develop and use effective, stage-appropriate treatment protocols.

(See the protocol of how to use motivational enhancement therapy appropriate to the client’s stage of recovery.)

Providing an appropriate level of care – matching to treatment

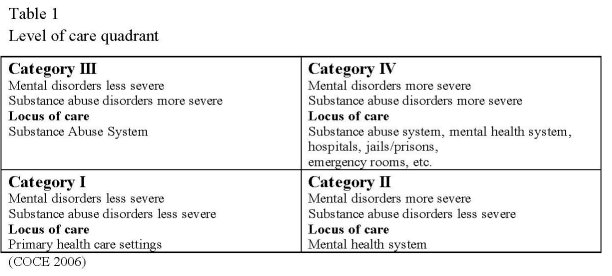

The Quadrants of Care, developed in the US and UK-research, and consensus building is a useful classification of service coordination by severity in the context of substance abuse and mental health settings. The four-quadrant framework provides a structure for fostering consultation, collaboration, and integration among drug abuse and mental health treatment systems and providers to deliver appropriate care to every client with COD. Although the material in this guidance relates to all four quadrants, the guideline is designed primarily for addiction counsellors working in quadrant II and III settings. The four categories of COD are

• Quadrant I: Less severe mental disorder/less severe substance disorder

• Quadrant II: More severe mental disorder/less severe substance disorder

• Quadrant III: Less severe mental disorder/more severe substance disorder

• Quadrant IV: More severe mental disorder/ more severe substance disorder (COCE 2008)

The quadrant represents a client placement system to facilitate effective treatment (following the American Society of Addiction Medicine – ASAM). In this guidance a related system is recommended that classifies both substance abuse and mental health programmes as basic, intermediate, and advanced in terms of their progress toward providing more integrated care.

• A basic programme has the capacity to provide treatment for one disorder, but also screens for the other disorder and can access necessary consultations.

• A programme with an intermediate level of capacity tends to focus primarily on one disorder without substantial modification to its usual treatment, but also explicitly addresses some specific needs of the other disorder.

• A programme with an advanced level of capacity provides integrated substance abuse treatment and mental health services.

Irrespective of the model adopted, services need to have close collaboration with other providers involved in the care of the patient and carers. Those involved in the care of the patient need to identify a named care co-ordinator with responsibility for co-ordinating care.

Achieving integrated treatment

Integration of care for COD is seen as a continuum. Depending on the needs of the client and the constraints and resources of particular systems, appropriate degrees and means of integration will differ.

Integrated treatment can occur on different levels and through different mechanisms:

• One clinician delivers a variety of needed services.

• Two or more clinicians work together to provide needed services.

• A clinician may consult with other specialties and then integrate that consultation into the care provided.

• A clinician may coordinate a variety of efforts in an individualized treatment plan that integrates the needed services.

• One programme or programme model (e.g., modified residential treatment or intensive outpatient treatment) can provide integrated care.

• Multiple agencies can join together to create a programme that will serve a specific population.

Integrated treatment also is based on positive working relationships between service providers. The four-quadrant category framework (described below) provides a useful structure for fostering consultation, collaboration, and integration among systems and providers to deliver appropriate care to every client with COD.

Ensuring continuity of care

Recovery for COD is a long-term process of internal change, and these internal changes proceed through various stages (De Leon 1996 and Prochaska et al. 1992). The recovery perspective generates at least two main principles for practice: A treatment plan should be developed that provides continuity of care over time. It should be considered that treatment may occur in different settings over time (i.e. residential, outpatient) and that much of the recovery process typically occurs outside of or following treatment. It is important to reinforce long-term participation in these continuous care settings. Continuity of care implies coordination of care as clients move across different service systems (e.g. Morrissey et al. 1997). Since both substance use and mental disorders frequently are long-term conditions, treatment for persons with COD should take into consideration rehabilitation and recovery over a significant period of time. To be effective, treatment must address the three features that characterise continuity of care:

• Consistency between primary treatment and ancillary services

• Seamlessness as clients move across levels of care (e.g. from residential to outpatient treatment)

• Coordination of present and past treatment episodes

Ideally outreach, employment, housing, health care and medication, financial support, recreational activities, and social networks should be included in a comprehensive and integrated service delivery system. Areas of particular value are housing and employment.

The different organisational structures and settings in which services occur influence the ease or difficulty of providing a service delivery network that is integrated, comprehensive, and continuous.

The support systems should be used to maintain and extend treatment effectiveness. The mutual self-help movement, the family, the faith community, and other resources that exist within the client’s community can play an invaluable role in recovery.

3.2 Guidelines for interventions and programme elements

Interventions refer to the specific treatment strategies, therapies, or techniques that are used to treat one or more disorders. Interventions may include psychopharmacology, individual or group counselling, cognitive-behavioural therapy, motivational enhancement, family interventions, 12-Step recovery meetings, case management, skills training, or other strategies. Both substance use and mental disorder interventions are targeted at the management or resolution of acute symptoms, ongoing treatment, relapse prevention, or rehabilitation of a disability associated with one or more disorders, whether that disorder is mental or associated with substance use.

Maintaining therapeutic alliance

Maintaining a therapeutic alliance with clients who have co-occurring disorders (COD) is important and difficult. Guidelines for addressing these challenges should be part of all interventions. It stresses the importance of the practicioners/counsellor’s ability to manage feelings and biases that could arise when working with clients with COD. To build a therapeutic relationship the above listed guidelines for treatment (see 3.1) and the attitude of motivational enhancement are essential.

Motivational Interviewing

Several well-developed and successful strategies from the substance abuse field should being adapted for COD. Motivational Interviewing (MI) is a client-centred, directive method for enhancing intrinsic motivation to change (by exploring and resolving ambivalence) that has proven effective in helping clients clarify goals and commit to change. (See special guidance for Motivational Enhancement for details).

Contingency Management (reinforcement approaches)

Approaches with reinforcement such as Contingency Management (CM) maintain that the form or frequency of behaviour can be altered through the introduction of a planned and organised system of positive and negative consequences. Many counsellors and programmes employ CM principles informally by rewarding or praising particular behaviours. Similarly, CM principles are applied formally (but not necessarily identified as such) whenever the attainment of a level or privilege is contingent on meeting certain behavioural criteria. Detailed demonstration of the efficacy of CM principles for clients with COD is still needed.

Cognitive–Behavioural Therapy (CBT)

Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy (CBT) uses the client’s cognitive distortions as the basis for prescribing activities to promote change. Distortions in thinking are likely to be more severe with people with COD who are, by definition, in need of increased coping skills. CBT should be introduced in developing these coping skills in a variety of clients with COD.

Relapse Prevention (RP)

Relapse Prevention (RP) has proven to be a particularly useful substance abuse treatment strategy and it appears adaptable to clients with COD. The goal of RP is to develop the client’s ability to recognise cues and to intervene in the relapse process, so lapses occur less frequently and with less severity. RP endeavours to anticipate likely problems, and then helps clients to apply various tactics for avoiding lapses to substance use. Relapse Prevention Therapy, has been specifically adapted to provide integrated treatment of COD, with promising results.

Ensure proper medication

The use of proper medication is an essential programme element, helping clients to stabilise and control their symptoms, thereby increasing their receptivity to other treatment. Maintenance treatment is introduced as a first line treatment (see special guidance). Pharmacological advances over the past few decades have produced more effective psychiatric medications with fewer side effects. With the support of better medication regimens, many people with serious mental disorders who once would have been institutionalised, or who would have been too unstable for substance abuse treatment, have been able to participate in treatment, make progress, and lead more productive lives.

Outpatient programmes with key elements of Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) or Community Reinforcement Approach (CRA)

Because outpatient treatment programmes are widely available and serve the greatest number of clients, it is imperative that these programmes use the best available treatment models to reach the greatest possible number of persons with COD. Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) and Community reinforcement Approach (CRA), historically designed in the US for clients with serious mental illness or substance use disorder, employ extensive outreach activities, active and continuing engagement with clients, and a high intensity of services. These approaches emphasises multidisciplinary teams and shared decision making. Structured psychosocial interventions (see special guidance) that adopt elements of the mentioned programmes should be introduced in Europe.

Intensive Case Management (ICM)

The goals of ICM are to engage individuals in a trusting relationship, assist in meeting their basic needs (e.g., housing), and help them access and use brokered services in the community. The fundamental element of ICM is a low caseload per case manager, which translates into more intensive and consistent services for each client. ICM has proven useful for clients with serious mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorders. Structured counselling (see guidance for psychosocial interventions) offers similar elements as ICM und should have similar effects in connection with low caseloads per counsellor. (It should be noted that direct translation of ICM models from the mental health settings in which they were developed to substance abuse settings is not self-evident. These initiatives likely must be modified and evaluated in such settings.)

Consideration of cultural contexts

Treatment providers are advised to view clients with COD and their treatment in the context of their culture, ethnicity, geographic area, socioeconomic status, gender, age, sexual orientation, religion, spirituality, and any physical or cognitive disabilities. The provider especially needs to appreciate the distinctive ways in which a client’s culture may view disease or disorder, including COD. Using a model of disease familiar and culturally relevant to the client can help communication and facilitate treatment.

Modifications in residential settings

Residential treatment for substance abuse occurs in a variety of settings, including long(12 months or more) and short-term residential treatment facilities, criminal justice institutions, and halfway houses. In many substance abuse treatment settings, psychological disturbances have been observed in an increasing proportion of clients over time; as a result, important initiatives have been developed to meet their needs. The principles and methods of residential models (see special guideline to psychosocial interventions) have to be adapted to the circumstances of the client, making the following alterations: increased flexibility, more individualised treatment, and reduced intensity.

Provisions for acute and primary care settings

Because acute and primary care settings encounter chronic physical diseases in combination with substance use and mental disorders, treatment models appropriate to medical settings are important. In these and other settings, it is particularly important that administrators assess organisational readiness for change prior to implementing a plan of integrated care. The considerable differences between the medical and social service cultures should not be minimised or ignored; rather, opportunities should be provided for relationship and team building.

Consideration of treatment for special subgroups

The needs of a number of specific subgroups of persons with COD can best be met through specially adapted programs. These include persons with specific disorders (such as bipolar disorder) and groups with unique requirements (such as women, the homeless, and clients in the criminal justice system). A number of promising approaches to treatment for particular client groups should be implemented, while recognising that further development is needed, both of disorder-specific interventions and of interventions targeted to the needs of specific populations.

Important elements after residential placement

Discharge planning is important to maintain gains achieved through residential or outpatient treatment. Depending on programme and community resources, a number of continuing care (aftercare) options should be made available for clients with COD who are leaving treatment. These options include mutual self-help groups, relapse prevention groups, continued individual counselling, psychiatric services (especially important for clients who will continue to require medication), and ICM to continue monitoring and support.

Aid for self help approach

During the past decade, dual recovery mutual self-help approaches have been developed for individuals affected by COD and are becoming an important vehicle for providing continued support in the community. These approaches apply a broad spectrum of personal responsibility and peer support principles, often employing 12-Step methods that provide a planned regimen of change. The practicioner/clinician can help clients locate a suitable group, find a sponsor (ideally one who also has COD and is at a late stage of recovery), and become comfortable in the role of group member.

Promotion of coordination and continuity of care

Continuity of care refers to coordination of care as clients move across different service systems and is characterised by three features: consistency among primary treatment activities and ancillary services, seamless transitions across levels of care (e.g. from residential to outpatient treatment), and coordination of present with past treatment episodes. Because both substance use and mental disorders typically are long-term chronic disorders, continuity of care is critical; the challenge in any system of care is to institute mechanisms to ensure that all individuals with COD experience the benefits of continuity of care.

Implementation of integrated interventions

Integrated interventions are specific treatment strategies or therapeutic techniques in which interventions for both disorders are combined in a single session or interaction, or in a series of interactions or multiple sessions. Integrated interventions can include a wide range of techniques. Some examples include

• Integrated screening and assessment processes

• Dual recovery mutual self-help meetings

• Dual recovery groups (in which recovery skills for both disorders are discussed)

• Motivational enhancement interventions (individual or group) that address issues related to both mental health and substance abuse or dependence problems

• Group interventions for persons with the triple diagnosis of mental disorder, substance use disorder, and trauma, or which are designed to meet the needs of persons with COD and another shared problem such as homelessness or criminality

• Combined psychopharmacological interventions, in which an individual receives medication designed to reduce cravings for substances as well as medication for a mental disorder. Integrated interventions can be part of a single programme or can be used in multiple programme settings.

Internal capability and care coordination

Recognising that system integration is difficult to achieve (and only an option for small groups of clients) and that the need for improved COD services in substance abuse treatment agencies is urgent, it is recommended that the emphasis should be placed on assisting the substance abuse treatment system in the development of increased internal capability to treat individuals with COD effectively.

Staffing – promoting multidisciplinary team

An essential component of treatment for COD should enhance staffing that incorporates professional mental health specialists, psychiatric consultation, or an onsite psychiatrist (for assessment, diagnosis, and medication); psycho-educational classes (e.g. mental disorders and substance abuse, relapse prevention) that provide increased awareness about the disorders and their symptoms; onsite double trouble groups; and participation in community-based dual recovery mutual self-help groups, which afford an understanding, supportive environment and a safe forum for discussing medication, mental health, and substance abuse issues.

Training of staff

All good treatment depends on a trained staff. It is from special importance to create a supportive environment for staff and encouraging continued professional development, including skills acquisition, values clarification, and competency attainment. An organisational commitment to staff development is necessary to implement programmes successfully and to maintain a motivated and effective staff.

References

American Society of Addiction Medicine (2001) Patient Placement Criteria for the Treatment of Substance-Related Disorders: ASAM PPC-2R. 2d Revised ed. Chevy Chase, MD: American Society of Addiction Medicine.

Anderson AJ (1997) Therapeutic program models for mentally ill chemical abusers. International Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation, 1(1), 21–33.

Baker A, Bucci S, Lewin TJ, Kay-Lambkin F, Constable PM, Carr VJ (2006) Cognitive-behavioural therapy for substance use disorders in people with psychotic disorders -Randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry, 188(5), 439– 48.

Baker A, Lewin T, Reichler H, Clancy R, Carr V, Garrett R, Sly K, Devir H, Terry M (2002a) Evaluation of a motivational interview for substance use within psychiatric inpatient services. Addiction, 97(10), 1329–1338.

Baker A, Lewin T, Reichler H, Clancy R, Carr V, Garrett R, Sly K, Devir H, Terry M (2002b) Motivational interviewing among psychiatric inpatients with substance use disorders. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 106(3), 233–240.

Barrowclough C, Haddock G, Tarrier N, Lewis SW, Moring J, O’Brien R, Schofield N, McGovern J (2001) Randomized controlled trial of motivational interviewing, cognitive behavior therapy and family intervention for patients with comorbid schizophrenia and substance use disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158(10), 1706–1713.

Bartels SJ, Drake RE, Wallach MA (1995) Long-term course of substance use disorders among patients with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 46(3), 248–251.

Bellack AS, Bennett ME, Gearon JS, Brown CH, Yang YA (2006) Randomized Clinical Trial of a New Behavioral Treatment for Drug Abuse in People with Severe and Persistent Mental IIlness. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63(4), 426–32.

Broome KM, Flynn PM, Simpson DD (1999) Psychiatric comorbidity measures as predictors of retention in drug abuse treatment programs. Health Services Research, 34(3), 791–806.

Brunette MF, Mueser KT, Drake RE (2004) A review of research on residential programs for people with severe mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Review, 23, 471– 481.

Brunette, MF, Drake RE, Woods M, Hartnett T (2001) A comparison of long-term and short-term residential treatment programs for dual diagnosis patients. Psychiatric Services, 52, 526– 528.

Budney AJ, Higgins ST (1998) A Community Reinforcement Plus Vouchers Approach: Treating Cocaine Addiction. Therapy Manuals for Drug Addiction: Manual 2. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Budney AJ, Higgins ST, Delaney DD, Kent L, Bickel WK (1991) Contingent reinforcement of abstinence with individuals abusing cocaine and marijuana. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 24(4), 657–665.

Burnam MA, Morton SC, McGlynn EA, Peterson LP, Stecher BM, Hayes C, Vaccaro JV (1995) An experimental evaluation of residential and nonresidential treatment for dually diagnosed homeless adults. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 14(4), 111–134.

Callaly T, Trauer T, Munro L, Whelan G. (2001) Prevalence of psychiatric disorder in a methadone maintenance population. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 35(5), 601-5.

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (1998) Addiction Counseling Competencies: The Knowledge, Skills, and Attitudes of Professional Practice. Technical Assistance Publication Series 21. DHHS Publication No. (SMA) 98-3171. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Charney DA, Paraherakis AM, Gill KJ (2001) Integrated treatment of comorbid depression and substance use disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 62(9), 672– 677.

COCE, Co-Occuring Center for Excellence (2006) Definition and terms relating to cooccuring disorders. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administrationís, Center for Mental Health Services and Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Link: www.coce.samhsa.gov.

Coffey R, Graver L, Schroeder D, Busch J, Dilonardo J, Chalk M, Buck J (2001) Mental Health and Substance Abuse Treatment: Results from a Study Integrating Data from State Mental Health, Substance Abuse, and Medicaid Agencies. DHHS Publication No. (SMA) 01-3528. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Compton WM 3rd, Cottler LB, Ben Abdallah A, Phelps DL, Spitznagel EL, Horton JC (2000) Substance dependence and other psychiatric disorders among drug dependent subjects: Race and gender correlates. American Journal of Addictions, 9(2), 113– 125.

Condelli, WS, Hubbard RL (1994) Relationship between time spent in treatment and client outcomes from therapeutic communities. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 11(1), 25–33.

De Leon G (1989) Psychopathology and substance abuse: What is being learned from research in therapeutic communities. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 21(2), 177–188. De Leon G (1996) Integrative recovery: A stage paradigm. Substance Abuse, 17(1), 51– 63.

Drake RE, Bartels SJ, Teague GB, Noordsy DL, Clark RE (1993) Treatment of substance abuse in severely mentally ill patients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 181(10), 606–611.

Drake RE, McHugo GJ, Clark RE, Teague GB, Xie H, Miles K, Ackerson TH (1998a) Assertive Community Treatment for patients with co-occurring severe mental illness and substance use disorder: A clinical trial. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 68(2), 201–215.

Drake RE, Mercer-McFadden C, Mueser KT, McHugo GJ, Bond GR (1998b) Review of integrated mental health and substance abuse treatment for patients with dual disorders. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 24(4), 589–608.

Drake RE, Mueser KT (1996a) Alcohol use disorder and severe mental illness. Alcohol Health and Research World, 20(2), 87–93.

Drake RE, Mueser KT (1996b) Dual Diagnosis of Major Mental Illness and Substance Abuse Disorder II: Recent Research and Clinical Implications. New Directions for Mental Health Services. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, Inc., 70.

Drake RE, Mueser KT, Clark RE, Wallach MA (1996a) The course, treatment, and outcome of substance disorder in persons with severe mental illness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 66(1), 42–51.

Drake RE, Mueser KT, McHugo GJ (1996b) Clinician rating scales: Alcohol Use Scale (AUS), Drug Use Scale (DUS), and Substance Abuse Treatment Scale (SATS). In: Sederer, L.I., and Dickey, B., eds. Outcomes Assessment in Clinical Practice. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 113–116.

Drake RE, Xie X, McHugo GJ, Shumway M (2004) Three-year outcomes of long-term patients with co-occurring bipolar and substance use disorders. Biological Psychiatry, 56, 749–756.

Drake RE, Yovetich NA, Bebout RR, Harris M (1997) Integrated treatment for dually diagnosed homeless adults. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 185(5), 298– 305.

Edwards J, Elkins K, Hinton M, Harrigan SM, Donovan K, Athanasopoulos O, McGorry PD (2006) Randomized controlled trial of a cannabis-focused intervention for young people with first-episode psychosis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 114(2), 109–17.

Epstein J, Barker P, Vorburger M, Murtha C (2004) Serious mental illness and its cooccurrence with substance use. Rockville, MD7 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies.

Evans K, Sullivan JM (2001) Dual Diagnosis: Counseling the Mentally Ill Substance Abuser. 2d ed. New York: Guilford Press.

Fletcher BW, Tims FM, Brown BS (1997) Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Study (DATOS): Treatment evaluation research in the United States. Psychology of Addictive Behavior, 11(4), 216–229.

Flynn PM, Craddock SG, Hubbard RL, Anderson J, Etheridge RM (1997) Methodological overview and research design for the drug abuse treatment outcome study (DATOS). Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 11(4), 230–243.

Godley SH, Godley MD, Pratt A, Wallace JL (1994) Case management services for adolescent substance abusers: A program description. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 11(4), 309–317.

Graeber DA, Moyers TB, Griffith G, Guajardo E, Tonigan S (2003) A Pilot Study Comparing Motivational Interviewing and an Educational Intervention in Patients with Schizophrenia and Alcohol Use Disorders. Community Mental Health Journal, 39(3), 189–202.

Haddock G, Barrowclough C, Tarrier N, Moring J, O’Brien R, Schofield N, Quinn J, Palmer S, Davies L, Lowens I, McGovern J, Lewis S (2003) Cognitive-behavioural therapy and motivational intervention for schizophrenia and substance misuse: 18month outcomes of a randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry, 183, 418–426.

Havassy BE, Alvidrez J, Owen KK (2004) Comparisons of patients with comorbid psychiatric and substance use disorders: implications for treatment and service delivery. Am J Psychiatry., 161(1), 139-45.

Hellerstein DJ, Rosenthal RN, Miner CR (1995) A prospective study of integrated outpatient treatment for substance-abusing schizophrenic patients. American Journal on Addictions, 4(1), 33–42.

Higgins ST (1999) Potential contributions of the community reinforcement approach and contingency management to broadening the base of substance abuse treatment. In: Tucker, J.A., Donovan DM, Marlatt GA eds. Changing Addictive Behavior: Bridging Clinical and Public Health Strategies. New York: Guilford Press, 283–306.

Higgins ST, Stitzer ML, Bigelow GE, Liebson, IA (1986) Contingent methadone delivery: Effects on illicit-opiate use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 17(4), 311– 322.

Hser Y, Grella C, Hubbard RL, Hsieh S, Fletcher BW, Brown BS, Anglin MD (2001) An evaluation of drug treatment for adolescents in 4 US cities. Archives of General Psychiatry, 58, 689–695.

Hubbard RL, Craddock SG, Flynn PM, Anderson J, Etheridge RM (1997) Overview of 1-year follow-up outcomes in the Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Study (DATOS). Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 11(4), 261–278.

Hubbard RL, Marsden ME, Rachal JV, Harwood HJ, Cavanaugh ER, Ginzburg HM (1989) Drug Abuse Treatment: A National Study of Effectiveness. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

Hulse GK, Tait RJ (2002) Six-month outcomes associated with a brief alcohol intervention for adult in-patients with psychiatric disorders. Drug and Alcohol Review, 21(2), 105–112.

Joe GW, Brown BS, Simpson D (1995) Psychological problems and client engagement in methadone treatment. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 183(11), 704–710.

Karageorge K (2001) Treatment Benefits the Mental Health of Adolescents, Young Adults, and Adults. NEDS Fact Sheet 78. Fairfax, VA: National Evaluation Data Services.

Kavanagh DJ, Young R, White A, Saunders JB, Wallis J, Shockley N, Jenner L, Clair A (2004) A brief motivational intervention for substance misuse in recent-onset psychosis. Drug and Alcohol Review, 23(2), 151–55.

Kessler RC, Nelson C, McGonagle K (1996a) The epidemiology of co-occurring addictive and mental disorders: Implications for prevention and service utilization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 66, 17–31.

Kessler RC, Nelson CB, McGonagle KA, Liu J, Swartz M, Blazer DG (1996b) Comorbidity of DSM-III-R major depressive disorder in the general population: Results from the US National Comorbidity Survey. British Journal of Psychiatry, 30, 17–30.

Knight JR, Goodman E, Pulerwitz T, DuRant RH (2000) Adolescent health issues: Reliability of short substance abuse screening tests among adolescent medical patients. Pediatrics, 105(4), 948–953.

Knight K, Hiller ML, Broome KM, Simpson DD (2000) Legal pressure, treatment readiness, and engagement in long-term residential programs. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 31(1–2), 101–115.

Knight K, Simpson DD, Hiller ML (1999) Three-year reincarceration outcomes for inprison therapeutic community treatment in Texas. The Prison Journal, 79(3), 337– 351.

Krausz M, Verthein U, Degkwitz P (1999) Psychiatric comorbidity in opiate addicts. Eur Addict Res., 5(2), 55-62. Lehman AF, Dixon LB (1995) Double Jeopardy: Chronic Mental Illness and Substance Use Disorders. Chur, Switzerland: Harwood Academic Publishers.

Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM (1998) Patterns of usual care for schizophrenia: Initial results from the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) Client Survey. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 24(1), 11–20.

Magura S, Nwakeze PC, Demsky SY (1998) Pre-and in-treatment predictors of retention in methadone treatment using survival analysis. Addiction, 93(1), 51–60.

Mangrum LF, Spence RT, Lopez M (2006) Integrated versus parallel treatment of cooccurring psychiatric and substance use disorders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 30(1), 79–84.

McHugo GJ, Drake RE, Brunette MF, Xie H, Essock SM, Green AI (2006) Methodological issues in research on interventions for co-occurring disorders. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 32, 655– 665.

McHugo GJ, Drake RE, Teague GB, Xie H (1999) Fidelity to assertive community treatment. Psychiatric Services, 50(6), 818–824.

McLellan AT, Arndt IO, Metzger DS, Woody GE, O’Brien CP (1993) The effects of psychosocial services in substance abuse treatment. Journal of the American Medical Association, 269(15), 1953–1959.

Menezes PR, Johnson S, Thornicroft G, Marshall J, Prosser D, Bebbington P, Kuipers E (1996) Drug and alcohol problems among individuals with severe mental illness in south London. British Journal of Psychiatry, 168(5), 612–619.

Milby JB, Schumacher JE, Raczynski JM, Caldwell E, Engle M, Michael M, Carr J (1996) Sufficient conditions for effective treatment of substance abusing homeless persons. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 43(1–2), 39–47.

Miller NS (1994a) Medications used with the dually diagnosed. In: Miller, N.S., ed. Treating Coexisting Psychiatric and Addictive Disorders: A Practical Guide. Center City, MN: Hazelden, 43–160.

Miller WR, Rollnick S (2002) Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change. 2d ed. New York: Guilford Press.

Minkoff K (1989) An integrated treatment model for dual diagnosis of psychosis and addiction. Hospital and Community Psychiatry, 40(10), 1031–1036.

Minkoff K, Drake R (1991) Dual Diagnosis of Major Mental Illness and Substance Disorder. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Morrissey J, Calloway M, Johnsen M, Ullman M (1997) Service system performance and integration: A baseline profile of the ACCESS demonstration sites. Access to Community Care and Effective Services and Supports. Psychiatric Services, 48(3), 374–380.

Morse GA, Calsyn RJ, Allen G, Tempelhoff B, Smith R (1992) Experimental comparison of the effects of three treatment programs for homeless mentally ill people. Hospital and Community Psychiatry, 43(10), 1005–1010.

Morse GA, Calsyn RJ, Klinkenberg WD, Trusty ML, Gerber F, Smith R, Tempelhoff B, Ahmad L (1997) An experimental comparison of three types of case management for homeless mentally ill persons. Psychiatric Services, 48(4), 497–503.

Mueser KT, Drake RE, Sigmon SC, Brunette MF (2005) Psychosocial interventions of adults with severe mental illnesses and co-occurring substance use disorders: a review of specific interventions. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 1(2), 57–82.

Mueser KT, Yarnold PR, Rosenberg SD, Swett C Jr, Miles KM, Hill D (2000) Substance use disorder in hospitalized severely mentally ill psychiatric patients: Prevalence, correlates, and subgroups. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 26(1), 179–192.

Narrow WE, Regier DA, Rae DS, Manderscheid RW, Locke BZ (1993) Use of services by persons with mental and addictive disorders: Findings from the National Institute of Mental Health Epidemiologic Catchment Area Program. Archives of General Psychiatry, 50(2), 95–107.

National Advisory Council (1997) Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Improving Services for Individuals at Risk of, or with, Co-Occurring Substance-Related and Mental Health Disorders. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors and National Association of State Alcohol and Drug Abuse Directors (1999) National Dialogue on Co-Occurring Mental Health and Substance Abuse Disorders. Washington, DC: National Association of State Alcohol and Drug Abuse Directors.

Onken LS, Blaine J, Genser S, Horton AM (1997) Treatment of Drug-Dependent Individuals with Comorbid Mental Disorders. NIDA Research Monograph 172. NIH Publication No. 97-4172. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Osher FC, Drake RE (1996) Reversing a history of unmet needs: Approaches to care for persons with co-occurring addictive and mental disorders. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 66(1), 4–11.

Oyefeso A, Clancy C, Ghodse H (1998) Developing a quality of care index for outpatient methadone treatment programmes. J Eval Clin Pract., 4(1), 39-47.

Pepper B, Kirshner MC, Ryglewicz H (1981) The young adult chronic patient: Overview of a population. Hospital and Community Psychiatry, 32(7), 463–469.

Pepper B, Massaro J (1995) Substance Abuse and Mental/Emotional Disorders: Counselor Training Manual. New York: The Information Exchange.

Petry NM, Martin B, Cooney J, Kranzier HR (2000) Give them prizes and they will come: Contingency management for the treatment of alcohol dependence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(2), 250–257.

Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC (1992) Stages of change in the modification of problem behavior. In: Hersen M, Eisler R, Miller PM, eds. Progress in Behavior Modification. Sycamore, IL: Sycamore Publishing Company, 184–214.

Rodríguez-Jiménez R, Aragüés M, Jiménez-Arriero MA, Ponce G, Muñoz A, Bagney A, Hoenicka J, Palomo T (2008) Dual diagnosis in psychiatric inpatients: prevalence and general characteristics. Invest Clin., 49(2), 195-205.

Rounsaville BJ, Weissman MM, Kleber H, Wilber C (1982b) Heterogeneity of psychiatric diagnosis in treated opiate addicts. Archives of General Psychiatry, 39(2), 161–168.

Sacks S, De Leon G, Balistreri E, Liberty HJ, McKendrick K, Sacks J, Staines G, Yagelka J (1998a) Modified therapeutic community for homeless mentally ill chemical abusers: Sociodemographic and psychological profiles. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 15(6), 545–554.

Sacks S, De Leon G, Bernhardt AI, Sacks JY (1997a) A modified therapeutic community for homeless mentally ill chemical abusers. In: De Leon, G., ed. Community as Method: Therapeutic Communities for Special Populations and Special Settings. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers/Greenwood Publishing Group, 19–37.

Sacks S, De Leon G, Bernhardt AI, Sacks JY (1998b) Modified Therapeutic Community for Homeless Mentally Ill Chemical Abusers: Treatment Manual. New York: National Development and Research Institutes.

Sacks S, De Leon G, McKendrick K, Brown B, Sacks J (2003a) TC-oriented supported housing for homeless MICAs. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 35(3), 355–366.

Sacks S, Sacks J, De Leon G, Bernhardt AI, Staines GL (1997b) Modified therapeutic community for mentally ill chemical “abusers”: Background; influences; program description; preliminary findings. Substance Use and Misuse, 32(9), 1217–1259.

Sacks S, Sacks JY, Stommel J (2003b) Modified TC for MICA Inmates in Correctional Settings: A Program Description. Corrections Today.

Saxon AJ, Calsyn DA (1995) Effects of psychiatric care for dual diagnosis patients treated in a drug dependence clinic. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 21(3), 303–313.

Schäfer I, Najavits LM (2007) Clinical challenges in the treatment of patients with posttraumatic stress disorder and substance abuse. Curr Opin Psychiatry., 20(6), 6148.

Schumacher JE, Milby JB, Caldwell E, Raczynski J, Engle M, Michael M, Carr J (1995) Treatment outcome as a function of treatment attendance with homeless persons abusing cocaine. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 14(4), 73–85.

Sciacca K (1991) Integrated treatment approach for severely mentally ill individuals with substance disorders. New Directions for Mental Health Services, 50, 69–84.

Silverman K, Svikis D, Robles E, Stitzer ML, Bigelow GE (2001) A reinforcement based therapeutic workplace for the treatment of drug abuse: Six-month abstinence outcomes. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 9(1), 14–23.

Simpson DD, Joe GW, Broome KM (2002) A national 5-year follow-up of treatment outcomes for cocaine dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry, 59, 538–544.

Simpson DD, Joe GW, Brown BS (1997a) Treatment retention and follow-up outcomes in the Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Study (DATOS). Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 11(4), 294–307.

Simpson DD, Joe GW, Fletcher BW, Hubbard RL, Anglin MD (1999) A national evaluation of treatment outcomes for cocaine dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56(6), 507–514.

Simpson DD, Joe GW, Rowan-Szal GA (1997b) Drug abuse treatment retention and process effects on follow-up outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 47(3), 227–

235. Solomon J, Zimberg S, Shollar E (1993) Dual Diagnosis: Evaluation, Treatment, Training, and Program Development. New York: Plenum Medical Book Co.

Stein LI, Test MA (1980) Alternative to mental hospital treatment: I. Conceptual model, treatment program, and clinical evaluation. Archives of General Psychiatry, 37(4), 392–397.

Swanson AJ, Pantalon MV, Cohen KR (1999) Motivational interviewing and treatment adherence among psychiatric and dually diagnosed patients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 187(10), 630–635.

Weisner C, Mertens J, Parthasarathy S, Moore C, Lu Y (2001) Integrating primary medical care with addiction treatment. JAMA, 286(14), 1715–1721.

Weiss RD, Griffin ML, Greenfield SF, Najavits LM, Wyner D, Soto JA, Hennene JA (2000) Group therapy for patients with bipolar disorder and substance dependence: results of a pilot study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 61(5), 361–367.

Weiss RD, Griffin ML, Kolodziej ME, Greenfield SF, Najavits LM, Daley DC, Doreau HR, Hennen JA (2007) A randomized trial of integrated group therapy versus group drug counseling for patients with bipolar disorder and substance dependence. American Journal of Psychiatry, 164(1), 100–107.

Wexler H, De Leon G, Thomas G, Kressel D, Peters J (1999) Amity Prison TC evaluation: Reincarceration outcomes. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 26(2), 147– 167.

Wingerson D, Ries RK (1999) Assertive Community Treatment for patients with chronic and severe mental illness who abuse drugs. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 31(1), 13–18.

Wittchen HU, Zhao S, Abelson JM, Abelson JL, Kessler RC (1996) Reliability and procedural validity of UM-CIDI DSM-III-R phobic disorders. Psychol Med., 26(6), 1169-77.

Wolff N, Helminiak TW, Morse GA, Calsyn RJ, Klinkenberg WD, Trusty ML (1997) Cost-effectiveness evaluation of three approaches to case management for homeless mentally ill clients. American Journal of Psychiatry, 154(3), 341–348.

Woody GE, Blaine J (1979) Depression in narcotic addicts: Quite possibly more than a chance association. In: Dupont R, Goldstein A, O’Donnell J eds. Handbook of Drug Abuse. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse, 277–285.

Woody GE, McLellan AT, O’Brien CP, Luborsky L (1991) Addressing psychiatric comorbidity. In: Pickens RW, Leukefeld CG, Schuster CR eds. Improving Drug Abuse Treatment. NIDA Research Monograph 106. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse, 152–166.

18 Principles and core elements are following the consensus building process about treatment of COD of the „Treatment Improvement protocol“ Nr 42 (SAMHSA 2005##).

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|