Unmet Drug and Alcohol Service Needs of Homeless People in London: A Complex Issue

Drug Abuse

Unmet Drug and Alcohol Service Needs of Homeless People in London: A Complex Issue

Jane Fountain, Samantha Howes and John Strang

Centre for Ethnicity and Health,

University of Central Lancashire. London, UK

National Addiction Centre, Institute of Psychiatry,

Maudsley Hospital, London, UK

ABSTRACT

Little research has been conducted on the drug use of those who sleep rough (on the streets) in the United Kingdom (UK). During 2000, to fill in the gaps in the knowledge base, researchers at the National Addiction Centre, London, carried out a community survey using a structured questionnaire amongst 389 homeless people recently or currently sleeping rough, in order to investigate their met and unmet drug and alcohol service needs. In total, 265 (68%) had a need for drug services and 97 (25°,/o) for alcohol services. Over half of the current drug users (170/324. 52%) and 88 (33%) of the 264 current alcohol users wanted help with their substance use, but few were currently accessing the appropriate services, other than needle exchanges. The challenge for services is to build these potential clients' motivation to accept health-conferring intervention.

Keywords: Homelessness; Drug services; Alcohol services; Needs assessment.

BACKGROUND

The number of people who are homeless in the United Kingdom cannot be accurately stated, due to the reliance on estimates, differences in the definition of "homeless,"(1) and the unknown numbers who do not appear in official statistics such as, for example, those applying to local authorities for social housing or being accommodated by friends (Fitzpatrick et al., 2000). In London alone, however, over 450 hostels provide around 19,600 beds for single homeless people (DTLR, 2001), and there have also been attempts, through street counts, to ascertain the numbers sleeping rough.121 In June 2000, the Rough Sleeper's Unit (RSU), a government initiative to tackle the problems of those sleeping on the streets, particularly those who have not been helped by previous initiatives, estimated that 1180 people were sleeping rough in England on any one night-535 of them in London (RSU, 2000). This population is not stable, however: the numbers sleeping rough annually are estimated to be at least live times higher than on any one night (Social Exclusion Unit, 1998). A target to reduce the prevalence of rough sleeping by two-thirds by 2002 has been set (Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions/DETR, 1999).

The RSU and the UK Anti-Drugs Co-ordination Unit (UKADCU, now renamed the Drugs Strategy Directorate, which was set up to devise and implement a national UK strategy on drugs) are working in partner-ship to tackle drug use amongst people who are sleeping rough (DETR, 1999). Fountain et al. (in press [a]), in a survey of substance use and home-lessness in London have shown that this partnership is timely: major drug and alcohol use-related problems are common amongst people sleeping rough in London, and homelessness and substance use are closely linked. However, when the strategy to reduce the numbers of those sleeping rough was devised CCorning in from the Cold'—DETR, 1999) and the RSU/ UKADCU partnership was formed, little research on the extent and significance of drug use amongst this population had been conducted. As Fitzpatrick et a (2000: 32) in a thorough review of the research on single homelessness in Britain, point out, "There is surprisingly little material on drugs in the health and homelessness literature, with several major studies discussing alcohol problems but not other substance depen-dencies." Nevertheless, the DETR's strategy estimates from previous research that 20% of those sleeping rough use drugs and 50% are alcohol reliant (DETR, 1999: 8).

The existing research literature suggests that simple causal explana-tions of the relationship between homelessness and substance use are inadequate: whilst the posited risk factors for homelessness and for health problems (including problematic substance use) are similar, cause and effect have proved difficult to disentangle (Bines, 1994; Duct] et al., 1997; Hutson and Liddiard, 1994; Johnson et al., 1997; Fountatin et al., in press [a]; Neale, in press). However, if interventions are not informed by better understanding of the relationship of these phenomena, they may be ineffective, or even counter-productive. In this paper, to inform t he develop-ment of service provision for drug and alcohol users who are sleeping roueh, data are presented on the sample's drug and alcohol dependence and the prevalence of injecting, and the related service needs and uptake. Respondents' knowledge of drug and alcohol services, reasons for their lack of uptake, and their suggestions for improvements are also discussed.

METHODS

A community survey using a structured questionnaire containine 58 items was conducted amongst respondents who had slept rough lbr at least six nights in the six months before the interview; since this was the only criteria for inclusion in the study, drug users were not targeted. Questions covered basic demographics; homelessness history; substance-using history (drugs and alcohol); past and present use of drug, alcohol, and homeless services; and income and expenditure. The questionnaire was piloted with ten homeless people, and adjustments made to, for example, facilitate respondents' understanding of some questions. Interviews were then carried out with a convenience sample between January and October 2000, in 20 locations across inner London, and took place in hostels, cold weather shelters. "rolling".(i.e., temporary) shelters, day centers, drop-in centers, and in the street. interviews lasted betvveen 25 and 45 minutes.

The marginalized population targeted by this study is hard to reach and likely to be reluctant to answer questions about their substance use. In order to minimize this occurrence, interviews were conducted by 10 members of a homeless oreanization's Substance Use Team

comprising six females and four males, with an average age of 31. This team was chosen because of their experience with the target client group and their ability to conduct interviews in a manner that was nonthreatening to /respondents, respectful of their values, and sensitive to the context in which the interview was taking place. This strategy was of critical importance to ensure maximum participation and that interviewees felt comfortable in expressing their views. Another advantage of the use of this interview team was that their established contacts with other relevant organizations facilitated their access to respondents who fitted the study criteria. Respondents were paid £10 (approx US $15, 15 euros) to participate in the project. Only three refusals were reported and only one interview had to be abandoned because a respondent was too under the influence of drugs and/or alcohol.

Interviewers were trained in the administration of the questionnaire by the research project manager. Before questioning began, interviewers read out the following to potential respondents: "This study is being conducted by Crisis [the funders, a well-known charity for homeless people] and is about homelessness and drug use. I will be asking you questions about both these things. A major aim of the study is to use the findings to inform those providing services for homeless people who also use drugs. I can assure you that everything you tell me is completely confidential: you need not give me your name and no information which can identify you will be passed on to anyone else. You don't have to answer any of the questions you don't want to, but please answer where you Ca n "

The following sections examine the sample's drug and alcohol service needs and compares them with their uptake of the relevant services, in order to assess their met and unmet service needs. Dependence on the main substance used in the last month was measured using a checklist of symptomsil derived from, and compatible with, both DSM-IV and ICD-10 (American Psychiatric Association, 1994; World Health Organisation, 1992). Measures were also incorporated to discover which drug and alcohol services respondents had used, and if they knew where they were and how to access them. Open-ended questions collected data on the reasons why services were not used and suggestions for improvement.

RESULTS

1. Demographics

The sample consisted of 389 homeless people. Almost half (187, 48%) had slept rough for more than six months in the year before the interview, including 67 (17% of the whole sample) who had slept rough the night before. Ahnost two-thirds (241, 62%) had been homeless (although not necessarily sleeping rough) for six years or longer, and over half (210, 54%) had first become homeless at the age of 18 or younger. Eighty-one percent were male and 19°,/0 female. and 83% gave their ethnic group as white. This compares with the total population of London (over 7 million), which is 50.9% female. and the proportion of Black and minority ethnic population which ranges from 4.61!‘)--55.9'.14) across the city's 33 boroughs (Department of Health, 2001). The average age of respondents was 31.1 (range 17-72), with 48 ( I ri't)) aged 21 and under; one-third (129, 33%) aged 25 and under; 286 (74%) aged 35 and under; and 18 (4.6%) aged 50 and over. Respondents' gender, age, race, and the inner London borough where they last slept rough broadly reflects government statistics of all those sleeping rough in London during the previous year (Fountain et al., in press).

2. Drug and Alcohol Use and Dependence

In the month before the interview, 372 (96%) respondents had used a drug and/or alcohol: 83% (324) had used a drug (excluding alcohol) and 68% (264) had used alcohol. As a comparison, the British Crime Survey (Ramsey et al., 2001) reports that 6% of the whole population of England and Wales aged 16-59 had used a drug in the last month. This proportion ranges from 3%-20')/0 according to age group, and is highest in London. The British Crime Survey is a survey of households, however, and does not interview homeless people.

Amongst the sample of this study, polydrug use was common: on average, drug-using respondents had each usecl three to four different drugs in the last month and only 48 (12`)/0) of the sample had used alcohol and no drug. Overall, substance use, injecting. daily use, and dependence increased the longer respondents had been homeless (further details of the drug and alcohol use of the sample, and the close link between becoming and remaining homeless are reported in Fotmtain et al., in press).

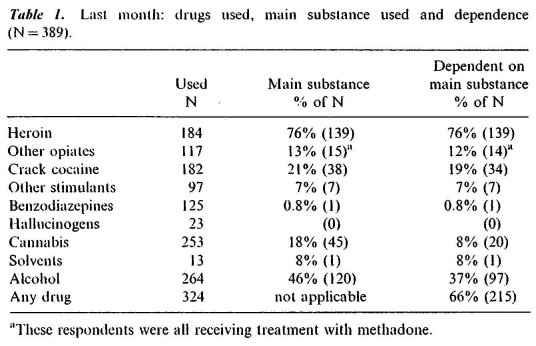

Those respondents who had used any drug and/or alcohol in the last month were asked to specify which was the main substance they had used in that period and to report their dependence on it. Two-thirds (66'!i), 215) of the 324 drug users were dependent on the main drue they had used in the last month. Table 1 shows that those who had used heroin were most likely to.report it as their main substance (139/184-76%), and all of these were dependent on it. One hundred eighty-two respondents had used crack cocaine, 38 (21°,10) reported it as their main substance. and 34 I (19%) were dependent on it. Forty-five (18%) of 253 respondents who had used cannabis said it vvas their main substance, and 20 (8%) were dependent on it. Opiates other than heroin, stimulants other than crack cocaine, benzodiazepine, or solvents were less often cited as a main substance. Of the 264 who had used alcohol in the last month, 120 (45%) cited it as their main substance and 97 (37%) were dependent on it. Dependence status was measured only on the main substance respondents reported ttsing in the last month, and therefore these results represent the mini-mum of drug and alcohol problems amongst the sample, as more used each substance than were dependent on it. For example, although 184 respondents (47% of the whole sample) had used heroin in the last month, only 139 (76°,10 of 184) cited it as their main substance.

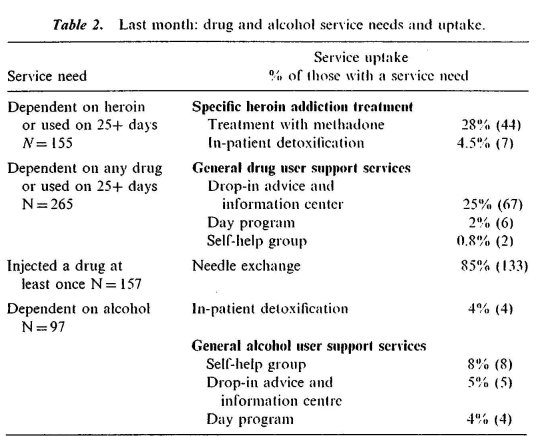

Note: Some respondents appear in more than one of the categories concerning drug use in both columns. The total with a need for drug services was 265 (82% of the current drug users).

3. Drug User Services

Need for Drug User Services

Drug services cover a range of interventions to cater to the needs of the users of a range of drugs. Not all services are suitable for all drug users. For example, only those dependent on heroin (or another, similar opiate) are treated with methadone, and, obviously, noninjectors do not require the services of needle exchanges. Thus, for the analyses in this paper, drug services have been divided into three groups: heroin addiction treatments (i.e., methadone maintenance and in-patient detoxification), general drug user support services (drop-in advice and information centers, Narcotics Anonymous or other self-help groups, and day programs), and needle exchanges.

The drug service needs and service utilization of the sample are summarized in Table 2. The diverse needs of those who had used a drug in the last month (N=324) have been examined in three ways. First, a need for specific heroin addiction treatment could only be applicable to those who were dependent on heroin. Hence, we have restricted this analysis to those who were dependent on heroin or who were using it on 25 or more days in the last month. One hundred lifty-five respondents (48°4 of the current drug users) fell into this category. Second, a need for general drug support services is not restricted to those using heroin, and so we have looked at all those respondents who reported dependence on any drug or had used any drug on more than 25 davs in the Iasi month.

5. Barriers to Uptake of Drug and Alcohol Services

The majority of respondents ^,vho would benefit from a drug or alcohol service were not in contact with them, despite the respondents themselves requesting help with their substance use. At the time of the interview, 170 (52% of the 324 current drug users) wanted help with drug use-related problems (136/80"/0 citing heroin) and 88 (33% of the 264 current alcohol users) wanted help with alcohol use-related problems.

If respondents had never used any drug or alcohol service from those listed above, they were asked would they consider using one in the future and if they had used it, they were asked if they would use the same service again. If they answered "no" to one or both of these questions, they were asked for the reason.

The majority of those with a need for drug services said they would consider using them in the future. Of the 155 respondents who had a need for specific heroin addiction treatment, 103 (66%) were prepared to have inpatient detoxification, and 105 (68%) were prepared to have treatment with methadone. Of the 265 who needed general drug user support services, 73"/o (195) said they would use at least one of these services in the future, and 95% (149) of the 157 injectors said they would use a needle exchange. The reason most often given by the majority of the remainder for not using drug services 1,vas that they were not needed. For example, this reason was given by 27 (52%) of the 52 who had a need for an in-patient drug detoxification but said they would not use this service; and by 54 (65%) of the 83 who had a need for general drug support services but would not use a drop-in advice and information centre.

Of the 97 respondents who were dependent on alcohol, 52 (54%) woukl use an alcohol detoxification unit in the future, and 54 (56°/o) a general alcohol user support service. The major reason given for the unwillingness of the remainder to use alcohol services was that they did not want to stop using alcohol and therefore did not feel the need for an alcohol service. This reason was given by 34 (76%) of the 45 who would not have an alcohol detoxification and by all the 43 (100%) who would not use a general alcohol user support service.

To explore the issue of barriers to service uptake further, those who said they would not use each drug or alcohol service were asked what the service could do to encourage them to do so. The most common response was "nothing." For example, this was the response of 26 (52%) of the 50 who had a need Ibr methadone treatment but would not use this service; 64 (77%) of the 83 who had a need for contact with a drug user drop-in advice and information service but would not use it; and 40 (89%) of the 45 who had a need for inpatient alcohol detoxification but would not accept this treatment.

6. Uptake of Services for Homeless People

It should be noted here that the sample's uptake of homelessness services was far higher than it was of drug and alcohol services (Fountain et al., 2002). For example, in the month before the interview, 235 (61%) of the sample had used a day center; 203 (52%) a food run (where food is distributed to people sleeping on the streets); 156 (409/0) the services of an outreach team; 134 (35°/0) a hostel; 113 (29%) a cold weather shelter (open only during the winter); 84 (22%) a rolling shelter (open for only a few months before moving to a new location); and 25 (6%) a night shelter (open only at night). In addition, far fewer said they would not use homelessness services in the future than said they would not use drug and alcohol services.

CONCLUSIONS

This study was conducted in London, which, although containing the highest concentration of homeless people in the United Kingdom, may not reflect the situation elsewhere. It should be repeated in other areas of the United Kingdom, to assess if the findings are applicable to other areas of the country.

The sample of this study is representative of all those "sleeping rough" in Inner London: that is, predominantly white and male. It is questionable, however, that the small proportion of women and members of Black and minority ethnic groups, in both the government's street counts and in the sample, means that members of these groups do not become homeless. They iriay be sleeping rough but hidden from counters and researchers, or they may be vulnerably housed (for example, sleeping on friends' floors or living in squats). This makes them susceptible to the development of future problems, including rough sleepinn and the concomitant substance use. Further research is required on the prevalence of homelessness amongst females and members of Black and minority ethnic groups and their associated service needs. These needs should then be addressed in order to prevent the development of future problems and demands on services.

Whilst the drug use and dependence of the sample was high, the uptake of drug services by those in need of them was low. If needle exchanges—which were well-used—are excluded, the great majority of those with a need were not accessing any drug service. Regarding specific §ervices, in the month before interview, only just over one-quarter of those dependent on heroin or using it daily or ahnost daily had received treatment with methadone, and a similar proportion of those who were dependent on the main drug they had used or were usiug it daily or almost daily had visited a drop-in advice and information center. Apart from needle exchanges, these two drttg services were by far those most accessed by the sample. Uptake of other drug services and of alcohol services was extremely low. The discrepancy between service need and service uptake is disturbing, particularly as over half the current drug users and a third of the current alcohol users wanted help with their substance use; as the majority of those with a need for drug and alcohol services were prepared to use them in the future; and as the majority knew where at least one service was located or how to access treatment.

That the majority of current injectors were currently using needle exchanges is a tribute to the success of this service in attracting clients and promoting harm reduction messages. Nevertheless, that even a minority (24/15% of the 157 injectors) may not be accessing sterile injecting equipment means that the transmission of blood-borne diseases amongst those sleeping rough remains a significant health threat.

The data in this paper indicate that the extent of drug use amongst people sleeping rough (83% of the sample) is greater that the government estimate that 20% are drug users, although the 37°/0 who were alcohol dependent is closer to the government figure of 50')/0 (DETR, 1999). As a consequence, estimates of the proportion dependent on drugs, and who therefore have a treatment need, are also too low. If resources were allocated to drug user treatment services for this group according the perceived need, they are inadequate. This would go some way to explaining the lack of uptake of these services by the sample and is pzirticularly pertinent to the relatively expensive provision of in-patient drug detoxification services. However, due to the chaos of the lives of some people sleeping rough, detoxification in the community (for example, with methadone for those addicted to heroin) is unlikely to be successful. Furthermore, even if an in-patient detoxification place is obtained for a person who was previously sleeping rough, unless tile appropriate aftercare—including measttres to prevent a return to homelessness—is also provided, a return to a chaotic environment where drug use is common means a relapse is highly likely.

Immediate clinical interventions for homeless substance users may not always be the most appropriate response to their needs, and when they are used, support services to prevent a return to substance use and to homelessness should be a priority. For example, to a person who has lived on the streets with other homeless people for many years, there may be aspects of the homelessness lifestyle which appear more attractive—or at least easier to follow—than living alone in their own home, newly detoxified from drugs or alcohol. Thus there is a need for longitudinal studies of those who have accessed drug and alcohol services in order to assess the processes and outcomes of these interventions.

The major reason that those in need of drug and alcohol services did not access them was that they did not feel the need for them, including that they did not want to stop using the substances they were using. The chal-lenge for services is to build these potential clients' motivation to accept intervention. Those setting targets to reduce the numbers of those sleeping rough and using drugs and alcohol should not overlook that successfully tackling rough sleeping and substance use may require long-term, non-coercive interventions from a range of services, including not only those addressing their clients' homelessness and substance use, but also their mental and physical health, and criminal activities perpetrated to fund their substance use. Service evaluations should identify those aspects which lead to a high level of uptake, which should then be publicized amongst those sleeping rough, and strengthened, in order to maximize uptake.

Polydrug use and the use of crack cocaine represent particular challenges to drug services. In many cases, alcohol is also a significant element of polydrug-using repertoires. Interventions for polysubstance users should be developed and successes used as models.

Some notable practice work is already taking place with substance users who were previously sleeping rough, and resources in the United Kingdom are increasingly being concentrated in efforts to engage this group, including a multi-agency approach. However, the data presented in this paper show that current drug and alcohol services are clearly not meeting the needs of people sleeping rough in London. The sample of this study used homelessness services in far greater numbers than they did drug and alcohol services: this suggests that a multi-agency approach may be more successful in engaging them in drug and alcohol services too.

Much remains to be done. The long-term needs of many drug and alcohol users who are sleeping rough will remain unmet unless the issues raised in this paper are addressed. One of the principles of the RSU strategy (DETR, 1999:9) is "Never give up on the vulnerable.- The data from this study suggest that there are more of this group than the government initially believed and that their service needs may be too complex for the current systetn of delivery. Despite the political priority status attached to both their rough sleeping and their substance use, the needs of this population are largely unmet.

NOTES

[1] In this paper, "homeless" refers to all those who have no home, and includes those living in hostels for homeless people, in temporary accom-modation provided for homeless people, and sleeping on the streets. "Sleeping rough" refers speCifically to homeless people who are sleeping on the streets.

[2] Several times a year, throughout the United Kingdom, the numbers sleeping on the streets are counted by special teams. It is widely thought, however, that many people sleeping rough are hidden—deliberately or otherwise—from these counters.

[3] Below is the checklist of symptoms derived from, and compatible with, both DSM-IV and ICD-10 (American Psychiatric Association, 1994; World Health Organisation, 1992) as it appeared in the study's questionnaire. Three or more "yes" responses indicate dependence. Instructions to interviewers are in italics.

Please answer the following questions about the main drug you have used in the last month (including alcohol).

If respondent does not use one drug more than any others (i.e., does not hare a "nuzin drug"), ask please ansvver about the drug which is giving you the most problems.

Which drug is this? (write in)

In the last month, did you:

tick one on/y

Have a strong or persistent desire to use (named dragl yes no

Have difficulty in controlling how much you used [named drugl 0

Need to use an increased amount of [named drug] to achieve the effect you wanted? 0

Find that when you continued to use the same amount of [named thig] it had less of an effect? 0 0

Feel sick or unwell when the effects of [named drag] had worn off? 0

Take more [named drag] or a similar drug to stop or avoid withdrawal symptoms? 0 0

Use [named drug] more than you intended'? 0 0

Spend most of the day obtaining, using and recovering from the effects of [named drugl

Find that [named drug] led you to neglect other things in your life'? 0 o

Continue to use inamed /kiwi despite having problems with your use'?

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to Crisis for funding support for the survey from which the data for this paper were taken, and to staff from St. Mungo's Substance Use Team for conductina the interviews with homeless people. Paul Griffiths, John Marsden, and Colin Taylor, from the National Addiction Centre, London, are thanked for their valuable help on the project. The views expressed are those of the authors.

REFERENCES

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington DC: APA.

Bines, W. (1994). The Health of Singk Homeless Peopk. York: Centre for Housing Policy, University of York.

Department of Health (2001). The on-line guide to the NHS in London.

DETR (Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions). (1999). Coming in ji.onz the Cold: The Government's S'irategi, on Rough Sleeping. London: Rough Sleepers Unit, DETR.

Ducq, H., Guesdon, I., Roelandt, J. L. (1997). Psychiatric morbidity of homeless persons: a critical review of the Anglo-Saxon literature. Encéphale Revue de Psychiatrie Clinique Biologique et Thempeuti-que November/December:420-430.

Fitzpatrick, S., Kemp, P., Klinker, S. (2000). Single Homelessness: An Overview of Research in Britain. Bristol: The Policy Press.

Fountain, J., Howes, S., Marsden, J., Strang, J. (2002). Who uses services for homeless people? An investigation amongst people sleeping rough in London. Journal of Community and ApPlied Social Psychology 12:71-75.

Fountain, J., Howes, S., Marsden, J., Taylor, C., Strang, .1. (In press). Drugs and alcohol and the link with homelessness: results from a survey of homeless people in London. Addiction Research and Theory.

Hutson, S., Lidddiard, M. (1994). Youth Homelessness: The Construction of a Social Issue. London: Macmillan.

Johnson, T. P., Freels, S. A., Parsons, .1. A., Vangeest, J. B. (1997). Substance abuse and homelessness: social selection or social adaptation? Addiction 4(2):I63-169.

Neale, J. (2001). Drug Users ill Society.Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Ramsey, M., Baker, P., Goulden, C., Sharp, C., Sondlii, A. (2001). Drug misuse declared in 2000: results from the British Crime Survey.

Home Office Research Study 224. Home Office Research, Development and Statistics Directorate. September 2001. London: Home Office.

RSU (Rough Sleepers Unit). (2000). 1999 estimate of the number of people sleeping rough in England. Statistics provided by Rough Sleepers Unit to the authors.

Social Exclusion Unit. (1998). Rough Sleeping: Report by the Social Exclusion Unit. London: Cabinet Office.

World Health Organisation (WHO). (1992). International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. 10th ed. Geneva: WI10.

Last Updated (Thursday, 20 January 2011 15:51)