EFFECTS IN MAN OF SHORT- AND LONG-TERM USE OF CANNABIS SATIVA

| Reports - Marihuana and Health |

Drug Abuse

EFFECTS IN MAN OF SHORT- AND LONG-TERM USE OF CANNABIS SATIVA

Cannabis sativa is one of man's oldest and most widely used drugs. It has been consumed in various ways as long as medical history has been recorded and is currently used throughout the world by hundreds of millions (2, 3, 81, 101, 211). A fairly consistent picture of its short-term effects is presented in the many publications on Cannabis users. There are, however, strongly contradictory opinions about whether the ultimate effects are harmful, harmless, or beneficial to human functioning (166). Despite these conflicting opinions, from the scientific point of view, the literature is as clear, if not clearer, than for many other botanical substances consumed by man. Most of the older reports suffer from multiple scientific defects such as biased sampling, lack of control groups and use of substances of unknown potency. However, contrary to popular belief, much is known about the use of Cannabis by man (67).

THERAPEUTIC USES OF CANNABIS

There is no currently accepted medical use of Cannabis in the United States outside of an experimental context. However, there was a time when extracts of Cannabis were as commonly used for medicinal purposes as aspirin today (127, 196).

Medical use of Cannabis is mentioned as early as 2737 B.C. when it was recommended in China for female weakness, beriberi, constipation, absentmindedness and surgical anesthesia. It was used medically in India before 1000 B.C. After 500 A.D., Cannabis spread westward to Persia and other Arabian lands, where it was used medically as a balm and an antiseptic. Cannabis was probably re-introduced to Europe by Napoleon's soldiers returning from Egypt, although it had been used during the Middle Ages to treat burns, earaches, ulcers and uterine disease (127, 149, 159, 196, 211).

There was only minor mention of Cannabis' psychoactive effects in ancient China although soon after its introduction in India, it became an integral part of the Hindu culture as a mind altering aid to meditation.

A British physician serving in India, W. B. O'Shaughnessy, rein- troduced Cannabis into Western medicine. In 1839 he reviewed the literature of its use in Indian medicine during the preceding 900 years, and he described his experiences with the drug in the treatment of seizures, rheumatism, tetanus and rabies. He found it an effective analgesic, anticonvulsant, muscle relaxant and sedative in man. Later in the 19th century its use in medicine spread rapidly. Numerous reports in the literature described its therapeutic effectiveness over an extensive range of ailments, including: gynecological disorders such as excessive menstrual cramps and bleeding (23, 190), treatment and prophylaxis of migraine headaches (12, 70, 176), alleviation of withdrawal symptoms of opium and chloral hydrate addiction (13, 132 , tetanus (73, 150, 158, 160), insomnia (132), delirium tremens (176 , muscle spasms (176) strychnine poisoning (88), asthma (59, 157 , cholera (157), dysentery (68), labor pain (48, 123), psychosis, spasmatic cough, excess anxiety, gastrointestinal cramps, depression, nervous tremors, bladder irritation, and psychosomatic illness (196).

However, the use of Cannabis preparations gradually disappeared from medical therapeutics at the end of the 19th century for the following reasons: unavailability of injectible preparations, difficulty in obtaining standard potency batches, wide variability of individual responses to the same dose. Also important was the introduction of a wide variety of synthetic drugs which were easier to produce and more efficient to administer although not always as effective and usually more toxic than Cannabis. Nevertheless, there were 28 pharmaceutical preparations containing Cannabis in use when passage of the Maripana Tax Act in 1937 effectively banned Cannibis as a medicine as well as an intoxicant (185, 196).

In 1947, experiments revealed that natural tetrahydrocannabinol and a synthetic derivative, synhexyl, were effective anti-convulsants (123). In 1949, THC was demonstrated to be effective in the control of seizures in several epileptic children who were unmanageable with the conventional drugs. THC was reported to have a synergistic effect with diphenylhydantoin and phenobarbital (48).

Recently, marihuana or its synthetic analogues have been experimentally considered for the treatment of the withdrawal of the chronic alcoholic (203) , and as a substitute for alcohol in chronic alcoholism therapy (147). Extracts of unripe Cannabis have also been demonstrated to have antibiotic activity against certain bacteria and fungi (66, 109, 173). Other THC analogues may prove to be valuable agents for the treatment of high blood pressure and uncontrollable fevers (191).

Some preliminary studies have suggested that an oral extract of marihuana may be a useful agent for the management of terminal cancer patients. The beneficial effects of marihuana demonstrated over a short period of time were stimulation of appetite, euphoria, increased sense of well-being, mild analgesia and an indifference to pain which reduced the need for opiates (199) .

Thus, Cannabis has had widespread usage in medical therapeutics for about 5,000 years. In the future, Cannabis or its synthetic analogues may prove to be valuable therapeutic agents (149, 196).

ACUTE EFFECTS: EXPERIMENTAL FINDINGS

It is important to recognize that the response to Cannabis varies according to the form in which it is consumed, the dose and the route of administration (typically by smoking or eating in humans). Also, the non-drug factors of set and setting must be considered in evaluating the results of those laboratory studies. In the following discussion dosages are expressed in terms of the Delta-9—THC content (the major psychoactive ingredient). Since it is only recently that laboratory reports routinely cite the percentage of THC, for older reports the estimated THC equivalent is based on the assumption that the average THC content is on the order of 1% for marihuana, 3% for Indian ganja and 5% for hashish. Although given samples may vary widely in actual THC content such a very rough measure is useful as the basis for comparisons between various experiments and observations. Actual THC content varies greatly depending on such variables as the parts of the plant included in the mixture, genetic origin and mode of cultivation. (Cf. Section III, The Material.)

DOSE AND ROUTE OF ADMINISTRATION

Four studies have described the effects of administering pure Delta9-THC (the major psychoactive ingredient in marihuana) to humans at oral doses of 5-70 mg. and smoked doses of 2-20 mg. Isbell, et al. (105, 106), reported that smoked material was nearly three times as effective as orally consumed material in producing equivalent peak pulse rate increases and subjective effects. His subjects, former opiate addict patients and experienced marihuana smokers, readily identified the marihuana-like effect of THC. Threshold doses of 2 mg. smoked and 5 mg. orally produced mild euphoria; 7 mg. smoked and 17 mg. orally, some perceptual and time sense changes occurred; and at 15 mg. smoked and 25 mg. orally, subjects reported marked changes in body image, perceptual distortions, delusions and hallucinations. Waskow, et al., (213), administered 20 mg. Delta-9-THC orally to "marihuana naive" prisoners. A slight euphoria, mildly unpleasant somatic effects and a few marked mental changes were noted. Hollister, et al., (98), elucidated the characteristic clinical syndrome of euphoria followed by sedation and sleep with marked psychic changes following oral administration of Delta-9-THC in doses of 30-70 mg. (median 50 mg.) , to students experienced with marihuana. Dornbush, et al., (156), demonstrated great variability among moderately experienced users in the dose range required to produce behavioral effects (anywhere from 5-20 mg. Delta-9-THC). 5 and 10 mg. doses were inadequate; 15 and 20 mg. doses produced variable changes. A 20 mg. dose administered in the fasting state produced "intense" changes, indicating the importance of gastro-intestinal absorption when the drug is taken orally.

Other experiments on humans have utilized either smoked marihuana or an oral extract of marihuana. The most extensive study was conducted by Mayor LaGuardia's Committee on Marihuana (134). Both marihuana users and non-users were tested with an oral marihuana extract (dose range 30-50 mg. THC and a few 330 mg. THC) with characteristic euphoria and clinical syndrome resulting at lower doses but with dysphoria at higher doses. Subjects who smoked were instructed to do so until they felt "high." A characteristic euphoria and clinical syndrome was produced, especially among the user group, at doses of 8-28 mg. THC.

Weil, et al., (218), found smoked marihuana (18 mg. THC) resulted in a relatively high level of intoxication among experienced users (134), but lesser subjective effects were reported by naive subjects. Meyer, et al., (144), reported that a 3.1-3.8 mg. THC dose or smoked marihuana produced the usual social high in casual and heavy users who were permitted to smoke as much as they chose. Clark, et al. (39, 40), reported on the behavioral effect of approximately 20, 30 and 45 mg. THC contained in an alcohol extract of marihuana- His marihuana-naive subjects experienced few behavioral effects at the lower two dose levels, but the 45 mg. dose produced the characteristic effects. However, experienced users studied by Jones, et al., (108), were able to detect the characteristic effects of an oral extract of marihuana at dosages as low as 4.5 mg. THC. Jones was impressed by the quantity and quality of the different subjective effects produced by the oral and smoked preparations. Interpretation of marihuana smoking may be complicated by the placebo effect. That is, an individual smoking an inert material similar in taste and odor to Cannabis may subjectively believe he is "high" although the material itself is without physiological effect.

Forney and Manno (127,128) using a specially constructed smoking machine have estimated that only 50% of the Delta-9—THC present in a marihuana cigarette is delivered unchanged to the smoker's lungs. There was very little change from Delta-9 to Delta-8—THC in the smoking process. The percentage of delivery did not change by varying inspiratory volume or the duration of each inhalation. Studies by Foltz, et al., (69), confirmed that 50% of the Delta-9—THC in a marihuana cigarette was destroyed (or lost) during the smoking process. No measurable conversion of Delta-9—THC to Delta-8—THC or vice versa was observed. There was 7% conversion to cannabinol and less than 2% to cannabidiol.

Similar time-action curves have been observed for pure Delta-9-- THC and marihuana (98,106,134). After smoking, symptoms began almost immediately and persisted for one hour at lower doses and 3-4 hours at higher doses. Symptom onset after oral administration requires from one half to one hour, reaches a peak in 2-3 hours, and persists for 3-5 hours for the lower doses and up to 8 hours or more for the larger doses.

In summary, the effective dose for experienced subjects is in the range of 2-20 mg. THC when administered by a single smoked dose. The comparable range for oral administration is 5-40 mg. Oral administration of doses above 40 mg. THC produce dysphoria and unpleasant somatic symptoms in many subjects. Comparable smoking dose levels are uncommon and have not been investigated. Subjective responses of naive groups tend to be much more variable and unpredictable than those of experienced users.

SUBJECTIVE EFFECTS

There is much individual variation in the psychological effects produced by Cannabis. The widely divergent accounts to be found in published papers may be accounted for in part by ethnic and social differences in the populations studied, and in part by the effects of different preparations of the drug.

The psychological effects of acute intoxication were first described in detail by Moreau de Tours, and even after the passa.ge of more than a century, it is difficult to improve on his clinical description. The effects he mentions include euphoria, excitement, disturbed assocations, changes in the perception of time and space, heightened auditory sensitivity, fixed ideas, rapidly changing emotions, and illusions and hallucinations (175).

In Westerners, though the order of events may vary a great deal, a typical sequence is euphoria with restlessness; then confusion, disturbed visual and auditory perception; then a dreamy state; and finally depression and sleep. On waking after sleep, there may be numbness, dysarthria, and some amnesia. Subjects drawn from Near Eastern populations, in contrast, may become gay or relaxed though it is not rare for anger to be expressed in some act of violence. Noisy laughter may be accompanied by feelings of sadness (175).

Tart (202) discusses common experiences of marihuana intoxication as related by users. Sensory perception is often subjectively improved, both in intensity and scope. Visual imagery is often quite vivid but under subjective control. The individual feels less concern with controlling his activities. Distortion of time, sense, and space perception are common. Common emotional effects are euphoria, relaxation, disinhibition and feelings of well-being. Commonly experienced cognitive effects at the time of use are a dulling of attention, fragmentation of thought, impaired immediate memory, altered sense of identity, increased suggestibility and a feeling of enhanced insight. Other less common effects are dizziness, a feeling of lightness, ataxia, nausea, hunger, paresthesias and exaggerated laughter. Mild psychotomimetic phenomena are experienced in a wave-like fashion with larger doses (greater than typical social usage). These include distortion of body image, depersonalization, visual distortions, synesthesia, dreamlike fantasies and paranoid reactions. Marked anxiety and panic may accompany these phenomena. Occasionally this may occur at relatively low doses with naive individuals. The anxiety and panic is usually alleviated if supportive friends are present. However, nearly all the common effects seem either emotionally pleasing or cognitively interesting and, therefore, highly desirable to many users.

PHYSIOLOGICAL EFFECTS

The most consistent physiological sign is an increase in pulse rate. This change is sufficiently dose-related and reproducible for use as a quantitative assay with both oral and smoked pure THC (106, 144). Smoked doses of 4 and 15 mg. Delta-9-THC have resulted in average pulse rate increases of 22 and 34, respectively; oral doses of 8 and 34 mg. produced increases of 18 and 33, respectively. Correlation between dose and pulse increase is not especially high across investigators, but all report increases of 10-40 beats for doses ranging from 2-70 mg. THC (42, 55, 98, 127, 128, 134, 213, 218). This occurs regardless of prior experience with marihuana. Two studies using doses up to 70 mg. Delta-9-THC, and an extract containing 255 ma. THC produced little or no electrocardiographic abnormalities (1057 134), or change in circulation rate.

Conjunctival injection (i.e. reddening of the eyes) is another highly consistent physical sign of intoxication (5, 6, 98, 105, 128, 213, 218). This finding has been detected with smoked doses as low as 2.5 mg. THC (127). Weil (218) found such reddening in all of his chronic marihuana users and in 8 out of 9 naive subjects using an 18 mg. THC dose. Swelling of the eyelids (6), ptosis (106), photophobia and nystagmus (5) have also been reported in some individuals. Enlargement of the pupils and a sluggish reaction to light were reported in earlier studies (133, 134). However, recent experiments in which pupil diameter was systematically measured revealed no dilation at doses up to 70 mg. THC (55, 98, 105, 218). In fact, Helper, et al. (89) using sophisticated instrumentation demonstrated a slight but consistent pupillary constriction present within 5 minutes of smoking, a preservation of nor- mal light responsiveness and a depression of pupillary responsiveness to near stimulation appearing in a few hours, probably representing fatigue and sleepiness. Frank, et al. (19, 72) demonstrated a marked and consistent increase in glare recovery time which persisted for several hours and was not dose related. Further tests revealed that this finding was not related to change in illumination threshold or pupil size. This may indicate a significant hazard in night driving. Studies on near and far visual acuity, eye muscle balance, visual field acuity, depth and color perception are incomplete. Caldwell, et al. (24, 25, 26) have demonstrated neither an impairment nor an improvement in objective visual acuity or in the perception of light brightness in naive and experienced users at 4-6 mg. smoked THC closes. Clark, et al. (39) demonstratf.A1 no effect on depth perception, duration of after image or visual motor coordination tests.

Reports on the effects of a wide range of marihuana dosages on blood pressure are inconsistent. Investigators using pure THC have reported slightly lowered blood pressure (98, 105, 213). Others have reported small increases (55, 134). Some have been unable to demonstrate any change using smoked or oral preparations (199).

Body temperature is generally unchanged (98, 106, 199). Little or no effect on respiratory rates (55, 105, 218), lung vital capacity or basal metabolic rate is noted. This is true over a wide dosage range (134). Dryness of the mouth and throat are uniformly reported (6). Increased frequency of urination is often reported, but increased urine volume has not been consistently recorded (6, 134). Another carefully controlled clinical investigation (199) revealed no changes following oral ingestion of a marihuana extract in such measures of kidney function as: routine urinalysis, fluid intake, and 24 hour urinary output, electrolytes, protein and creatinine. Eight subjects and dosages ranging from 7.5 mg. to 52.5 mg. were studied. Hollister (98) also demonstrated no change in normal 24 hour creatinine excretion. The LaGuardia Commission also found no change in kidney function (134).

BIOCHEMICAL EFFECTS

Reports of increased hunger especially for sweets during Cannabis intoxication have focused attention on possible changes in blood sugar level (5, 6, 127, 134). Early investigators reported decreases (12, 121), but more recent studies have found no change (56, 92, 98, 105 127, 199, 218) or a slight increase (128 134) or both (153). Hollister, et al. (92) found an increase in total food intake which was significant after 26 mg. THC when the subject had eaten breakfast but not when he was in the fasting state. Reports of appetite stimulation and subjective hunger occurred in slightly more than half of the subjects. Hollister was unable to demonstrate a change in blood sugar. Free fatty acid levels were unchanged while a decrease was observed in the placebo control group.

Hollister (93, 98) analyzed blood and urine samples subsequent to oral administration of either THC (15-70 mg.) or synhexyl (50-150 mg.). Total white blood cells increased and absolute eosinophils decreased. No significant changes were demonstrated in platelet serotonin content, plasma cortisol level or urinary catecholamine excretion. These findings indicate a lack of major effects of marihuana on these physiological measures of stress. This differs significantly from findings in schizophrenics and individuals treated with LSD or mescaline who show such stress reactions. The hypothesis has been advanced that in most individuals the profound euphoriant and sedative effect of marihuana may serve to prevent the stress of the psychotomimetic experience that results with high dosages of THC.

Two studies (134, 199) have examined possible marihuana induced hematological and blood chemistry changes. No changes were found in: red blood cell structure or number; differential and total white blood count; platelet count; reticulocyte count; blood urea nitrogen; concentration of sodium, potassium, chloride, bicarbonate, calcium, phosphorous; liver function tests (alkaline phosphatase. bilirubin, SGOT) ; protein electrophoresis • uric acid. concentration. Doses ranged from 7.5 mg. to 75 mg. Tile equivalent.

NEUROLOGICAL EFFECTS

Neurological examinations have consistently revealed no major abnormalities (134, 180, 199) during marihuana intoxication. Muscle strength and performance of simple motor tasks are, however, affected. Several investigators (65, 98, 134) noted decreased leg, hand and finger strength at oral dosages of 50 to 75 mg. THC. However, electromyography has been reported to be within normal limits even at up to 52.5 mg. THC taken orally (199). Most investigators (98, 105) have not demonstrated change in threshold for elicitation of deep tendon reflexes although Rodin (180) described a slightly increased briskness in the knee jerk. Fine hand tremors are often reported (6, 12, 40, 134). Decrements in hand steadiness and static body equilibrium appear to be dose-related phenomena (127, 134) although other investigations have been unable to demonstrate these (180, 199). Other cerebellar dysfunctions are not evident. Cranial nerve function and somatic sensation were unimpaired (180).

Cannabis users often report increased auditory sensitivity and esthetic appreciation of music. Objective tests of auditory acuity including pitch, frequency and intensity or threshold discrimination

have been found to be unchanged (4, 24, 25, 26139, 134). However, two earlier investigators (211, 223) reported objective improvement in

auditory acuity in several of their subjects.

Improvement in visual acuity is often reported by users of marihuana. However, investigators have been unable to demonstrate significant changes in objective visual acuity, brightness discrimination (24, 25, 26) or visual flicker fusion frequency discrimination (39). Depth perception estimating length of lines (39, 134) and field inde- pendence measured by the rod-and-frame test are all unchanged (94, 108).

Rodin (180) has demonstrated a slight but statistically significant improvement in vibratory sense. Both Rodin and Williams, at al. (223) found other sensory discriminations including touch and two point discrimination unchanged. However, one investigator, Rumpf, reported an impairment in two-point discrimination (211). Pain sensitivity has been shown to be decreased (199) as is also suggested by marihuana's early medical use as an analgesic. No change has been demonstrated in olfactory threshold or in taste discrimination (223).

One of the most frequently reported effects of intoxication is a distortion of the sense of time. Time is almost always overestimated, that is, perceived as being longer than clock time. This phenomenon has been experimentally confirmed by most investigators (6, 40, 56194, 218, 223) , and is much greater for filled as opposed to unfilled time, i.e., when the subject estimates the elapsed time while performing a task. This overestimation is found for tune periods ranging from seconds to hours. Overestimation error appears to increase with longer time periods (40). thllister found that the overestimation of time produced by marihuana intoxication was much closer to clock time than the gross underestimation induced by alcohol or dextroamphetamine ingestion (94) .

Reported changes in resting electroencephalogram (EEG) during single dose administration have generally been minimal, inconsistent and within normal limits with rare exceptions. Early investigators generally, recorded an increased abundance of low voltage fast activity and a slight decrease in alpha wave percentage and frequency (222, 223). This has been reported recently in several subjects by Jones (108) . Recently, several investigators have shown no statistically significant alteration of normal EEG with only minor variation between subjects at doses of THC up to 52.5 mg. orally (6, 199, 108). Rodin (180) has detected a slight but statistically significant shift toward the slower alpha frequencies (9 to 10 cycles per sec.) in 10 experienced marihuana users who smoked to achieve their usual "social high." The average dose of THC consumed was 10-12 mg. Hollister confirmed this finding of increased and more synchronized alpha rhythm using 32 mg. Tile orally in 16 subjects (99) . There was no change in peak or mean frequency or total waves noted. This minimal EEG change resembled drowsiness or sleepiness and was not readily distinguishable on visual inspection from the placebo control EEG when drowziness also occurred. Preliminary studies by Rickles appear to support these findings (177) . In addition, Rodin (180) has reported no significant change in cerebral evoked potentials at 15 different sites for light, sound and passive joint movement. He also found no significant change in photic driving response. Jones (108) described a decrease in visual evoked response in preliminary work. Thus far, EEG findings following acute administrations at levels of social usage do not suggest changes in brain functioning indicative of gross cerebral dysfunction. Adult EEG wave changes are considered significant clinically only at frequencies less than 8 cycles per second. This occurs characteristically in certain toxic and degenerative central nervous system processes.

Preliminary work on the effect of marihuana on sleep has demonstrated an increase in total Rapid Eye Movement (REM) sleep time (177) . (This is the deep period of sleep when dreaming occurs.) Rickles (178) has also done preliminary work on evoked palmar skin resistance and evoked heart rate responses during marihuana intoxication. The former was greater and more variable and subjects demonstrated delayed habituation to it.

PSYCHOMOTOR AND COGNITIVE EFFECTS

Intoxication with psychoactive substances affect psychomotor and cognitive functions. Marihuana is no exception as is apparent from the assertions of users. Experimental confirmation is evident from a wide range of studies (39, 40, 42, 56, 94, 108, 127, 128, 134, 136, 141, 142, 144,186,217, 218).

In general, above a threshold dose of 15-30 mg. orally or 4-10 mg. smoked, a performance decrement or impairment on a wide range of tests occurs. In many instances7 the degree of impairment is dose related and varies during the period of intoxication. A minimal decrement is observed, both subjectively and objectively, at lower dosages and during the time period when the level of intoxication is increasing or declining. A moderate impairment occurs at higher dosages and during the period of peak intoxication.

Naive subjects do not react the same as do experienced marihuana users at the same dose levels. Naive subjects commonly report less marked subjective effects than those reported by experienced users. However, naive subjects demonstrate greater decrement in actual performance (218). Experienced users seem better able to compensate for the acute dreg on ordinary kinds of performance, at least at lower dose level's (39, 40, 42, 108, 144, 217) .

The complexity of the task is related to performance while intoxicated. Simple and familiar tasks are minimally affected. But, if the task is complicated enough, decrements in performance are demonstrable (217). In addition, the effects of marihuana are not consistent from subject to subject with marked individual differences in performance (39,40,127).

The intensity of the intoxication and the degree of related performance deficit varies cyclically from moment to moment. This contributes to the considerable variability in performance between, subjects and in the same subject at different times (40, 141).

In summary, marihuana in acute administration appears to act as a mild mental intoxicant in a neutral laboratory setting (108, 218). At the level of intoxication characteristic of the normal social high," it produces a subtle alteration in emotional state characterized by a feeling of euphoria, excess jocularity, and a minimal but subtle impairment of higher intellectual functioning. In most instances, this alteration in mental functioning is not consistently recognizable by an observer who does not know the user has received the active drug. Typically no gross unusual behavior, inability to function or intellectual performance is apparent. When subjects concentrate on the task being performed, no objective evidence of intoxication may be apparent. The subjects are easily able to "suppress the marihuana high' at least on the simpler, more familiar tasks (180).

Marihuana users consistently report interference with short-term and immediate memory functions (202). Researchers have therefore focused experimental investigation on these areas. Very simple memory tasks (forward and backward digit span) have given mixed results (134, 141, 213). More complex tasks in which memory and mental manipulations are required show larger dose related impairment (108, 134, 141, 213). This exemplified by simple cognitive functions performed while distracted by delayed auditory, feedback or background noise (127). More complex cognitive functions such as learning of a digit code (40), digit-symbol substitution (218), reading comprehension (40), speech (217) and goal directed arithmetic tasks (141) are all impaired.

Clark (40) suggests that marihuana affects the mental processes involved in recent memory and types of decision requiring recent memory and sustained alertness. Weil (218) describes subtle difficulties with speech experienced by marihuana smokers. The primary difficulty found was in "remembering from moment to moment the logical thread" of the conversation. He hypothesizes that more effort is necessary when "high" to retrieve information from the brain's immediate memory storage.

Melges, et al. (141) demonstrated that marihuana intoxication significantly impaired the ability to : (1) retain events from the preceding few seconds to minutes; (2) shift attention appropriately from one focus to another; and (3) to organize and coordinate serially in time recent information while pursuing a goal directed task. He termed the result of these inabilities "temporal disintegration," that is, difficulty in retaining, coordinating and indexing serially in time those memories, perceptions and expectations which are relevant to the goal being pursued. He theorizes that episodic impairment of immediate memory is the basic cause of these difficulties. He suggests that extraneous perceptions and thoughts occupy the void in thought created by the memory lapse, thus causing disorganized speech and thinking.

Melges (142) also suggests that "temporal disintegration" is associated with "depersonalization" during marihuana intoxication. He hypothesizes that impaired immediate memory leads to a "fragmentation and disorganization of temporal experience." This blurring of the personal past, present and future context in which the individual has his personal identity causes him to experience himself as strange and unreal (depersonalized) during Marihuana intoxication. Melges feels that the response to depersonalization is unique for individuals. When the distortion of self is recognized as time-limited and drug related, it is usually experienced as pleasurable. But when an individual's personality causes him to fear that loss of his identity and self-control of self may not end, acute anxiety and panic reactions may result.

DRIVER PERFORMANCE

There are two preliminary studies of the effect of social marihuana intoxication on automobile driving performance. Crancer (42) studied the effect of smoked marihuana (22 to 66 mg THC) on simulated driving performance. The subjects were seated in a console model of a recent car and performed the usual driving maneuvers in response to a series of situations portrayed in a film. Experienced and naive subjects demonstrated no significant decrement in accelerator, brake, turn signal, steering and speed variables as compared to non-drug control subjects. Subjects intoxicated with alcohol to the legal intoxication level (100 mg % blood alcohol concentration) made significantly greater errors (15% more) than both the non-drug control and marihuana subjects. Intersubject variation was observed during marihuana intoxication. Thus about one-half the subjects did better and one-half worse than the controls. The subjects indicated that their driving per- formance was affected but that they could compensate by driving slowly and cautiously. It should, of course, be noted that the legal level of alcohol intoxication is probably higher than typical levels of social. use of alcohol. By contrast the dose of marihuana used in this research may have more closely approximated a typical level of social marihuana use.

McGlothlin et al. (136) believe laboratory measures of attention skills are one of the best predictors of actual driving performance. He has demonstrated that oral or smoked marihuana (dose 15 mg THC) produces decrements in measures of vigilance, divided attention and psychological refractory time as does alcohol (peak blood alcohol concentration 68 mg %, in comparison to placebo controls). Perhaps this apparent discrepancy can only be resolved in a more complex, sophisticated simulator which accurately reflects the complexities of actual driving.

GENETIC EFFECTS

Concern over the possible role of cannabis in causing birth defects is an inevitable consequence of our generally increased awareness of the teratogenic and mutagenic potential of drugs. Although there are two isolated case reports (28, 85) of birth defects in the offspring of parents who have used both cannabis and LSD it is impossible to attribute a causal role to the drugs. Because of these findings Neu et al. (154) have examined the effects of Delta-8 and Delta-9-1"HO added to human micro-blood cultures. This caused a marked decrease in the rate of cellular division but did not cause structural damage.

Because of the basic importance of the question of birth defects associated with drug use, researchers are pursuing the inquiry. It should, however, be emphasized that there is little basis at present for suspecting that cannabis use is likely to lead to such defects. Nevertheless, the use of any drug substance of unknown teratogenic or mutagenic properties is obviously unwise especially by women during the child bearing years.

METABOLISM

One study has been published regarding the biological fate of Delta-9-THC in man. Lemberger et al. (119) injected a tracer dose (0.6 mg) of radioactivity labeled Delta-9-THC intravenously into three marihuana naive subjects and followed its course in blood, urine and feces. They found that Delta-9-THC is completely metabolized in man. The metabolites appear in the blood within ten minutes, 30% are excreted in the urine and 50% in the feces over a period of eight days. Most are excreted in the first few days. Delta-9-THC in the plasma declines rapidly during the first hour after injection and more slowly thereafter. The initial rapid decline, occurring in the first few hours, probably represents metabolism and a redistribution of Delta9-THC from the blood to the tissues (including brain). This is followed by a slow declining phase over the next three days which presumably represents retention and slow release from tissue stores. Negligible amounts of Delta-9-THC are excreted in the urine and feces. In the present study, the 11-hydroxy-Delta-9-THO metabolite appears to be only a minor metabolite of the Delta-9-THC and the remainder consists of unidentified more polar compounds. No data are presently available dealing with metabolic disposition of THC in experienced marihuana users.

PHARMACOLOGICAL CLASSIFICATION

The chemistry and clinical pharmacology of marihuana is distinct from that of the opiates, ethyl alcohol, barbiturates, amphetamines, atropine alkaloid-like drugs and psychotomimetic compounds (e.g., LSD, mescaline, psilocybin). However, the pharmacological action of marihuana has some similarities to properties of the stimulant, sedative, analgesic and psychotomimetic classes of drugs.

In large doses, cannabis drugs bear many similarities to the psychotomimetics. Isbell (104, 105) described marked distortion of auditory and visual perception, hallucinations and depersonalization. He found LSD was 160 times more potent as a psychotomimetic than Delta-9-THC. The wave-like experiencing of effects is also similar for both types of drugs (40, 141). However, there are numerous differences between cannabis and the strong hallucinogens: increased body temperature, blood pressure and constricted pupils do not occur with THC (19, 72, 89, 104, 105) or related synthetic analogues (19) ; sharply increased pulse rate and conjunctival reddening are common for cannabis but not for LSD (95) or mescaline (96) ; cannabis intoxication ends in sedation and sleep while wakefulness is characteristic of LSD and mescaline; acute changes in brain wave patterns characteristic of LSD are absent with marihuana (99, 108, 181) ; tolerance is not appreciable, at least at the usual doses for cannabis but occurs very rapidly with the psychotomimetics ; there is no cross-tolerance in man between LSD and Delta-9-THC (104) ; the subjective effects of even large doses of marihuana are milder and more easily controlled than those for LSD. The differing subjective effects of the two drugs are readily distinguished by users (104), and Delta-9-THC and marihuana even at high doses (70 mg) appear to lack the major effects on biochemical and clinical measures of stress found with the psychotomimetics (93, 95, 96).

In low doses, the effects of marihuana and alcohol are similar. Both produce an early excitant and later sedated phase, and are commonly used as euphoriants, relaxants and intoxicants. At low doses, subjects experience difficulty differentiating the effects of alcohol from marihuana and placebo. This difficulty is apparent especially when the marihuana and placebo are smoked and smell and taste senses are intact. But, this appears to diminish as the dosage is increased. The marihuana high is subjectively easily distinguishable from alcoholic intoxication (92, 94, 108, 127).

The margin of safety for Delta-9-THC is far greater than that of ethyl alcohol (19). In large doses alcohol acts as a general anesthetic producing a primary and continuous depression of the central nervous system. Experiments have shown that alcohol decreases mental and physical performance but does not alter sensory perceptions. It does slow brain wave rhythms (179).

Hollister et al. (94) compared the effects of 95% ethyl alcohol (50— 60 gm dose) and marihuana extract (27-37 mg THC dose) on mood and mental function. He found alcohol and marihuana similar in their effects except for the alteration of perception that was produced by marihuana but not by alcohol. Both produced decreased activity, euphoria and sleepiness, and decreased performance on psychometric tests. Marihuana led to moderate overestimation of time while alcohol produced grossly exaggerated underestimation of time. Thus, the estimate of elapsed time during marihuana intoxication was more accurate than with alcohol. Hunger and food consumption were increased by marihuana and decreased by alcohol. Neither. changed blood sugar level but alcohol decreased free fatty acid level (92).

Manno et al. (128) compared the effect of smoked marihuana (5-10 mg THC) with a subintoxicating level of alcohol (50 mg % blood alcohol concentration which is about the level produced by three bottles of beer in a 150 lb man) on performance on a pursuit rotor task and on mental function tests while distracted by delayed auditory feedback. This alcohol level was the threshold level to produce decrements in performance in a previous study with these tests. He concluded that performance decrement produced by marihuana was equivalent to that produced by alcohol. The combination of alcohol and marihuana generally led to a poorer performance than either drug alone.

In summary, marihuana cannot be accurately classified with specify-. ina dose level. In small doses stimulation is followed by sedation. In high doses, particularly with Delta-9-THC or concentrated oral extracts of marihuana, psychotomimetic effects are possible, but these are rarely attained (or sought by users) with smoked marihuana. Pharmacologically, cannabis is unique and distinct from the following hallucinogens, opiates, barbiturates, and amphetamines. Qualitatively, as an acute psychoactive agent, marihuana resembles alcohol but does not produce the same central nervous system and general physiological effects associated with alcohol.

CHRONIC EFFECTS: EXPERIMENTAL FINDINGS

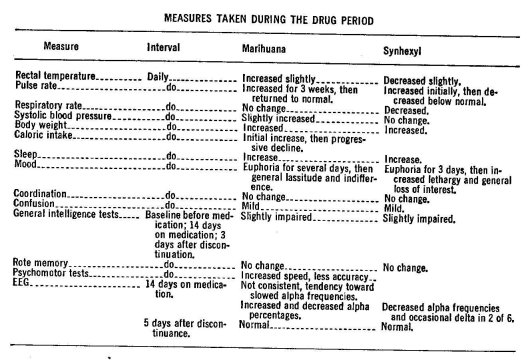

Marihuana has been administered to human subjects for extended periods of time in only a few studies. Williams (223) reported in 1946 on the oral administration of synhexyl (a synthetic marihuana analogue) for 26 days and marihuana cigarettes for 39 days to prisoners who were experienced marihuana smokers. Subjects were permitted to consume the drugs freely in any quantity they desired. The number of marihuana cigarettes (no estimate of the Delta-9-THC content available) used increased slightly over the 39 day period. The range was from 9 to 26 with a mean of 17 per day. The mean amount of synhexyl consumed by the second group of six subjects increased steadily from 200 mg the first day to 1600 mg daily at the 26th day. Three days after discontinuation of synhexyl, subjects reported restlessness, poor sleep, reduced appetite, "hot flashes" and perspiration. One sub]ect exhibited a brief hypomanic reaction and another developed a severe emotional reaction. However, there was no observable abstinence syndrome following the abrupt termination of marihuana smokine, Thus, there was only minimal evidence of the possible development of physical dependence or tolerance to marihuana. Tolerance and physical dependence did appear to develop to oral synhexyl. The effects of synhexyl are slower m onset and last longer than Delta-9-THO (98).

Siler (189) in 1933 reported on the results of an experiment in which marihuana cigarettes were freely available to 34 subjects for an average of six days. The daily mean consumption was 5 cigarettes per day (range 1 to 20). No abstinence symptoms nor ill effects were noted.

In a recent preliminary study (199), oral marihuana extract was administered to eight terminal cancer patients (age range 20-78; mean 54.4 years daily for from 4-13 (mean 8.5 days). Calculated daily doses of THC were progressively raised by the investigator from 7.5 mg to a maximum of 52.5 mg with a mean dose of 19.8 mg THC per patient per day. Total THC dose per individual patient ranged from 75-210 mgs with a mean of 168 mg. All eight patients experienced euphoria, 1 of 8 had an episode of acute anxiety, 3 of 3 gave objective evidence of pain relief as measured by decreased opiate analgesic requirements, 5 of 8 reported improved appetite, 4 of 8 had mild hallucinations at the higher drug levels, and 5 of 6 demonstrated improvement in depression (Beck scale). No significant changes were found in physical condition, neurological status and a wide range of blood and urine laboratory findings were unchanged. Fed adverse physchological effects were noted and potential therapeutic effects were demonstrated. Therapeutic effects found were decreased depression, increased appetite and analgesia. There was no evidence of physical dependence and no abstinence symptoms were reported after abrupt discontinuation of the drug. Although drowsiness was common, lethargy, lassitude and indifference were not noted.

Mirin (152) has studied a group of male heavy marihuana smokers who had used the drug for an average of 4.4 years about 20 to 30 times a month. For 3 of the 4.4 years (range 1/2-5 years), they had smoked virtually every day. Another group of casual marihuana smokers, comparable in age (25 years), educational experience (1 year graduate level), racial distribution (predominantly white) and social class (parents of higher socio-economic backgrounds) used marihuana 1 to 4 times a month for less than 2 years. Heavy marihuana use appeared to be correlated with: psychological dependence, search for insight or meaningful experience, multiple-drug use, poor work adjustment, diminished goal directed activity and ability to master new problems, poor social adjustment and poor heterosexual relationships.

Meyer (144) has been able to compare the effect of smoked marihuana on these two groups in the laboratory. In preliminary experi- ments, subtle differences are observed which may indicate the presence of tolerance to some of the effects of smoked marihuana in heavy ( daily) users. The total quantity of marihuana consumed to obtain a "very high" state judged subjectively was slightly less for the heavy user group (3.12 ma THC for heavy vs. 3.78 mg THC for casual group) not a statistically significant difference. The heavy users showed smaller pulse rate increases and less subjective and mood effects. Minimal to no impairment was seen in the heavy user group on perceptual and psychomotor performance tasks while the casual users showed decrements in these functions. The findings are generally consistent with the differences in performance noted in naive and chronic marihuana users by other investigations (39, 40, 108, 134, 218) .

HEALTH CONSEQUENCES FOR THE INDIVIDUAL OF MARIHUANA USE

In this section, health consequences will imply any toxicity which is directly related to consumption of marihuana or related substances. Toxic reactions are defined as any effects that result in physical or psychological damage, that the user subjectively experiences as unpleasant or that produce significant interference with adequate social functioning. Thus, the relaxed feeling of well-being or "high" is not considered toxic. Three factors are relevant to toxicity: the drug itself, including dose, frequency and duration of use; the personality, mental state and mood and expectations of the individual; and the setting or environment of drug use (193).

SHORT-TERM EFFECTS

The acute physical effects of marihuana intoxication including bloodshot eyes, burning or itchy eyes, dry mouth, excessive hunger, lethargy, rapid pulse have been discussed in previous sections and will not be repeated. These are minor effects of the drug and should not be considered major toxic reactions. The acute mental effects of the intoxication, including a variety of perceptual alterations, short-term mem- ory loss, temporal disorientation, and depersonalization considered toxic reactions by many are frequently desired by the user. Such subjective reactions may sometimes progress to acute anxiety attacks and even acute psychoses in some cases. It is noteworthy that these acute physical and mental effects consistently appeared in the scientific lit- erature of the late 19th century as a "toxic manifestation" of medrcal use of cannabis preparations (127).

Ungerleider, et al. (208) in 1968 concluded a survey of 2700 psychiatrists, psychologists, internists and general practitioners in Los Angeles regarding parents' adverse reactions to hallucinogenic drugs. "Adverse reactions" reported ranged from mildly unpleasant parental objections to use to severe anxiety or acute psychosis. Although 1887 "adverse reactions" were reported among these patients, the actual role of hallucinogenic drugs in causing the symptoms is not clear. The major implication of the study is that, among persons who are receiving professional help for personal problems, drug use mixed with personality dysfunction is frequently found.

The Haight-Ashbury Free Community Medical Clinic over a two year period from its opening in the summer of 1967, has treated over 40,000 young people for medical and psychiatric problems (193). These people include college students, professionals, working class people, as well as members of the Haight-Ashbury Free Community. 90 to 95% of its clients have had experience with marihuana (192). Smith (192, 193) has reported on the acute and chronic toxicity of marihuana in this population. Smith states that the role of the drug itself is overemphasized as a factor in toxicity.

Physical damage directly resulting from marihuana use alone is unproven at present (192). Although a few scattered reports of deaths associated with cannabis use are to be found in the literature, (17, 49, 62, 90, 101) there have not been any reliable reports of human fatalities attributable purely to marihuana (193). Very high doses have been given without causing death and the median lethal dose has not been established in man (19). Most of the fatalities are reports from Indian experience in the 19th century with large oral doses of charas (hashish).

A recent cast report (100) presented the association of eating large amounts of marihuana over a 3 day period with• the occurrence of severe diabetic coma and ketoacidosis in a young male without a family history of adult onset diabetes. The patient had not previously exhibited any symptoms of diabetes. No other precipitating factors were evident. The author speculates that the stress of marihuana ingestion may have been greater than the adaptive capacity of a marginal glucose regulating system. It is difficult to interpret the significance of such isolated case reports.

Other reported cases (78, 87, 116) relate severe physiological disturbances following intravenous injection of boiled suspensions of cannabis in multiple drug users. Chills, muscle aches, weakness, abdominal cramps, slowed respiratory rate and low blood pressure were uniformly observed. Other patients experienced diarrhea, vomiting, very rapid pulse, elevated body temperature, enlarged spleen and liver, pulmonary congestion and abnormal kidney function. These symptoms are believed to be primarily due to the reaction to intravenous injection of a foreign material.

Some of the most common toxic reactions which have been encountered at the Haight-Ashbury Medical Clinic are nausea, dizziness' and a heavy, drugged feeling where every movement required extreme effort (193). These reactions represent getting "too stoned." Most frequently, they occur with oral consumption or in inexperienced marihuana smokers. Due to the rapid onset of psychoactive effect, smoking usually allows the experienced individual to control or "self-titrate" his dose to achieve a desired "high". Thus, he is able to stop smoking at the first sign of subjectively defined unpleasant effects. This ability to control dose and effect is not available to the inexperienced smoker or when the drug is consumed orally.

Another factor may explain the clinical observation that heavy chronic users of marihuana can tolerate higher doses without encountering acute (physical and mental) toxicity. This factor is tolerance. Smith (193) suggests a "J" shaped time curve of tolerance to marihuana. A novice exhibits a moderate degree of tolerance. With in- creasing experience with the drug, he "learns to get high" causing a reverse in tolerance. That is, he requires less drug to reach his desired high. With chronic heavy use, tolerance increases again.

Some (119, 138) have suggested that a biochemical phenomenon accounts for tolerance and reverse tolerance. Possibly the enzyme necessary to metabolize Delta-9-THC to an active agent requires some prior marihuana use to develop sufficiently. The maximum attainable quantity of this enzyme may be the factor that controls the development of tolerance with chronic use.

Whatever the cause, the evidence suggests that mild tolerance to cannabis develops with chronic use of large doses (35, 51, 62). However, more moderate use for many years may not necessitate increasing doses (188). It is doubtful that Indian ganj a and charas smokers could consume an estimated 720 mg THC average daily dose without having developed some degree of tolerance (35). Other investigations have found that smoked doses of 20 mg THC and 70 mg Delta-9-THC orally often produce dysphoric reactions n experienced but non-heavily using marihuana smokers (105, 134).

Both Weil (216) and Smith (192) believe that non-drug factors play the most important role in the occurrence of acute toxic reactions. That is, the effect of marihuana on the individual depends to a large extent on the interaction of drug effect with the individual's psychological makeup, expectations, attitudes, mood and the physical and emotional circumstances surrounding drug use. The great variability in these factors makes the effect of marihuana rather unpredictable in many circumstances.

Fifty percent (50%) of the acute toxic cases in the Haight-Ashbury Medical Clinic (193) and 75% of those seen in hospital practice by Weil in Boston and San Francisco represent "novice anxiety reactions' or panic reactions (216). In these cases, the individual interprets the physical and mental effects of the drug to indicate he is dying or "losing his mind." The large majority of these occur in novices who often have strong underlying anxiety surrounding marihuana use such as fears of arrest, of disruption of family and occupation relations, and/or of possible physical and mental dangers.

The majority of these reactions appear to occur in people with relatively rigid personality structures (193). In the presence of psychological stress, simple transient neurotic depressive reaction may occur in these same types of individuals. According to experienced clinicians, both these types of reactions are transient and require simple, gently but authoritative reassurance that nothing is seriously wrong with the user and that the drug effects will wear off in several hours (193, 216). Several other investigators reported a number of cases of this type (8, 9, 79, 82, 165, 188).

Numerous reports of cases of acute psychosis precipitated by cannabis use usually associated with existing stress have recently been reported in the literature (5, 20, 21, 86, 100, 105, 110, 134). However, these appear to be relatively infrequent under most conditions of casual use (113, 193, 216). These psychotic episodes may occur in persons with a history of mental disorder, in individuals who are marginally adjusted or in those who have poorly developed personality structures (192). Marihuana intoxication may hinder the ability of the individual to maintain structural defenses to existing stresses or else produce a keener awareness of personality problems or existing stresses in the individual. Psychotherapy and antipsychotic medication are useful in the control and prevention of these reactions (216).

Weil (218) reports an exceptionally rare occurrence of nonspecific toxic psychosis or acute brain syndrome occurring after an oral overdose of marihuana. He believes that certain toxic constituents of cannabis may get into the body when the substance is eaten but which are destroyed or non-volatilized in the smoking process. This type of reaction has, however, also been reported in the eastern experience to accompany increased amounts of smoked cannabis over a short period of time (11). These toxic psychoses appear to be self-limited. Similar reports of brief, self-limited psychoses have been observed during experimental administration of high doses or oral marihuana or THC (6, 106, 134, 223).

Well (218) also reports marihuana intoxication may trigger a delayed psychotic reaction in a small percentage of persons who have previously taken other hallucinogenic drugs. Since such reactions may occur without subsequent marihuana use, the exact role of marihuana in precipitating them is uncertain.

DEPENDENCE AND WITHDRAWAL

Sedation and sleep are the immediate after effects of acute intoxication, especially when used in the evening. Williams (223) reported increased amount of time spent sleeping during chronic use. Pivik, et al. (167) have reported that oral administration of 20 mg Delta-9- THC or marihuana extract slightly decreased total Rapid Eye Movement (REM) time in two sleeping subjects. However, Rickles, et al (177) have presented preliminary data suggesting a subtle effect on sleep time. He found that four marihuana smokers who used one or two cigarettes per day for at least one year often in the evening, demonstrated a slight increase in total REM sleep time.

This total increase was primarily due to a, moderate increment in REM time during the last one-third of the night.

Most accounts of non-medical use report minimal hangover effects (134, 137, 223). After heavy use' some have reported feelings of lassi- tude and heaviness of the head. Lethargy, irritability, headaches and loss of concentration have also been reported, usually associated with large doses and lack of sleep (35, 101).

Reports based on Indian experience suggest neither severe physical or psychic dependence, nor severe withdrawal symptoms even after abrupt termination of very heavy usage (292 74, 1242 130, 189, 211). Evidence of possible physical dependence with physical withdrawal symptoms following discontinuation of heavy use and of appreciable psychic dependence s suggested by the Studies of the Indian Hemp Commission (101), Chopra (32) and Bonquet (18). Abstinence symtoms most reported were physical prostration, intellectual apathy (18) , loss of appetite, flatulence, constipation, insomnia, fatigue, abdominal pain and uneasiness (117). Psychic dependence may) however, be an important obstacle to discontinuing cannabis use. For example, 65— 70% of Soueif's (195) hashish users were reportedly unable to stop theiehabitual cannabis use although the average frequency was only 8-12 times per month. Studies in the U.S. using much lower doses for shorter time periods than Eastern studies have thus far found no evidence of psychic or physical dependence (21, 134, 223).

CHRONIC PHYSICAL EFFECTS

The only physical effect firmly linked to long-term cannabis use at present is permanent congestion of the transverse ciliary vessels of the eye and an accompanying yellow discoloration (6, 32, 52, 62). No other chronic physical damage has been satisfactorily demonstrated although there are other suspected or reported effects. It is noteworthy that many of the experimental studies of acute and chronic drug effects discussed earlier used as subjects individuals with at least one year and often longer histories of moderate to heavy marihuana usage. However, none were able to differentiate between these subjects and naive subjects with respect to physical or laboratory findings.

The LaGuardia report (134) of 1944 indicates no evidence of organic damage to the cardiovascular' digestive, respiratory and central nervous system or to the liver, kidney and blood in individuals who had used from 2-18 marihuana cigarettes (an average of 7) daily for a period of from 21/2 to 16 years (an average of 8 years). Another less comprehensive examination of 310 persons with an average usage of marihuana of seven years duration concluded the subjects suffered no mental or physical deterioration (75). The Indian Hemp Drugs Commission (101) of 1894 reached the following conclusion : generally the moderate use of (cannabis) appears to cause no appreciable physical injury of any kind. Excessive use does cause injury. The report on cannabis in 1968 of the Advisory Committee on Drug Dependence of the United Kingdom (The Wootton Report) concluded after an extensive review "that the long-term consumption of cannabis in moderate doses has no harmful effects." Howevert the Interim Report of the Commission of Inquiry into the non-medical use of drugs (102) concluded "there is hardly any reliable information applicable to North American conditions concerning the long term effects of cannabis." The results of studies in Eastern countries are of questionable applicability to North American conditions because of the significant differences in many of the variables determining drug effect. These differences include physiological and psychological condition of the people; conditions of nutrition, sanitation and climate; potency, drug dose level and frequency of use; and other drug use. The Canadian Commission stated there was no way of drawing comparisons with the Eastern levels of "moderate use" referred to by the Indian Hemp Commission and Wootton Reports and the levels of use that might occur in North America if the substance were freely available and socially accepted. The Canadian Commission also believed that the experimental design of the LaGuardia study was not up to modern standards so that its conclusions raised serious reservations. It lacked double-blind and placebo controls and adequate statistical analysis of data. The reporting of results was not entirely unbiased. Small numbers of subjects were used and the relevance of a prisoner sample to a more normal population has been questioned.

Bronchitis, asthma and a high incidence of respiratory problems are a frequently claimed effect of chronic use (35). The Indian Hemp Commission concluded that chronic and excessive smoking of ganja and charas could produce these conditions. It is noteworthy that Eastern smoking mixtures frequently contain both cannabis resin and tobacco. Mann (126) et al. reported that modern electron microscopic methods able to discriminate pulmonary tree lining cells of non-smok- ers from tobacco smokers, detected no difference between non-smokers and long-term marihuana only smokers.

Indian users have been reported to exhibit a high incidence of digestive difficulties, diarrhea, constipation, weight loss and sleep disturbance (35, 195) . However, the effects of poor living conditions and the prevalence of communicable disease may have been contributing factors to these symptoms in that culture.

Arteritiss was found in high percentage of heavy Moroccan Kif users (197) . This may be related to the finding of tropic foot ulcers in chronic users (153). The significance, if any, of these scattered findings is at this time not clear.

Kew (116) has suggested a possible role or cannabis in mild liver dysfunction in eight persons who smoked marihuana for 2-8 years at least six times a week. Several of these patients also admitted to use of alcohol and oral amphetamines but denied that they used opiates or amphetamines intravenously. Liver function tests disclosed some evidence of mild liver dysfunction which was confirmed by minimal changes in liver biopsy on three of the subjects.

MENTAL DETERIORATION AND PSYCHOSIS

The term mental deterioration covers many aspects of disturbed mental functioning, but for the most part studies fall into three major categories; mental illness, brain damage, and the so-called amotivational synirome.

For the most part, a connection between marihuana and mental illness like those of a connection between marihuana and violence, is based on studies done in countries which are underdeveloped scientfically as well as economically. Most of these studies suffer from biased sampling, poor data collection techniques, and a failure to control for such important variables as level of nutrition, socio-economic status, overall standard of living, as well as cultural determinants. Many of these cultures do not sanction the use of alcohol. As a result the potentially drug dependent may turn to more easily available and less expensive cannabis preparations.

In evaluating the significance of overseas studies of the relationship of cannabis use to mental deterioration it is important to recognize the comparatively low level of attention that can be paid to psychiatric illnesses and to the fate of the mentally ill in countries where life for the bulk of the population is one of marginal survival and there are more pressing public health problems. Here crippling chronic illnesses long since eliminated in the West are still endemic, and mental hospitals and trained psychiatrists do not rank high on the list of national health priorities. Yet some of the most widely quoted studies in the literature on marihuana and psychosis have originated from poorly staffed and maintained psychiatric hospitals, operating with a minimum of professionally trained psychiatrists.

The Indian Hemp Drugs Commission paid particular attention to the question of possible mental deterioration connected with cannabis use, since at the time it was formed the common impression was that consumption of hemp drugs (particularly to excess) produced insanity. In addition, statistics from Indian mental institutions were widely quoted to support the connection between cannabis and metal illness.

From the standpoint of modern scientific methodology, the Indian Hemp Commission report can be faulted in a number of ways2 but in its examination of the relationship of cannabis to psychoses, this work is still impressive for its thoroughness and objectivity.

The Commissioners questioned the popular impression that marihuana use leads to insanity because "the unscientific popular mind rushes to conclusions and naturally seizes on that fact of the case that lies most on the surface." They noted that in England itself there were wide variations between hospitals in the frequencies of the various types of mental diagnosis. In India, a good part of this variation was found to arise from the fact that diagnoses were made on the basis of a "descriptive role" that was sent to the hospital at the time the patient was admitted. This "descriptive role" was typically filled out not by a psychiatrist, or even a physician, but by a magistrate or a policeman. Since neither the magistrate nor the policeman had the capacity to make an accurate diagnosis, they frequently used the diagnostic category of insanity due to excessive consumption of hemp, for lack of any more obvious cause.

The Commission, convinced of the unreliability of the existing hospital statistics, examined all admissions to Indian Mental ilospitals in one year, 1892, in order to make its own diagnosis. Of 1344 admissions, the commission found that cannabis consumption could be considered to be a factor in no more than 7-15% of the cases (101).

A second major study done in India by the Chopras examined mental hospital admissions in India from 1928 through 1939, and found only 600 cases which could be traced solely and unambiguously to the use of cannabis. At the time this study was done, the number of users of cannabis of all types was extremely high in India (36).

South African mental hospitals have reported about 2 to 3% of their admissions due to dagga smoking, and in Nigeria 11% of psychiatric admissions were users and one half of these were cannabis related.

Studies based on several hundreds of cases indicate that the large majority can be classified as acute psychoses, and are associated with a "sharp toxic overdose" or with "massive excesses" among habitual users. The clinical picture is that of a severe exogenous psychosis—delirium with confusion, disorientation, terror or anger, and subsequent amnesia about what happened during the period of intoxication (36).

Eastern authors uniformly report fairly short recovery times ranging from a few days to six weeks. This is in sharp contrast to the lengthy recovery period typical of the functional psychoses.

The symptomatologyof the acute pyschosis is highly varied and often similar to schizophrenia at the outset. Several studies have called attention to the confused, manic aspects which frequently characterize the state and sometimes lead to impulsive acts of violence. These clinical manifestations are particularly important in any attempt to assess the overall prevalence of psychoses among cannabis smokers through examination of mental hospital records. Socially disruptive behavior in both Eastern and Western countries is still a prime predictor of possible hospitalization for mental illness. Although the symptomatology of the acute psychosis is highly varied and often similar to schizophrenia at its onset, the acute cannabis psychosis does not typically involve the type of thought disorders characteristic of schizophrenia. Thus, it appears that this acute cannabis psychosis etescribed in the Eastern literature is similar to the acute toxic psychosis currently being reported at lower doses in less chronic marihuana users in the Western World.

The existence of a more long lasting cannabis-related psychosis is less well defined. There appears to be some evidence to support the existence of a slow-recovery, residual (2-6 months) cannabis psychosis following heavy chronic use. The symptoms developed gradually tend to subside rather than developing into full-blown psychotic systems. Long-term patterns of acute and subacute psychotic episodes accompanying continued heavy use have also been described. These may produce gradual psychic deterioration in habitual excessive users after prolonged periods of time. Western experience has involved a level of cannabis usage substantially below that of these Eastern studies and the associated psychic disturbances are not generally comparable.

OTHER MENTAL EFFECTS

Another group of symptoms that have been described on a worldwide basis as associated with heavy chronic cannabis use is called the amotivational syndrome (32, 36, 38, 101, 182, 212). In its extreme form it represents a loss of interest in virtually all other activities other than drug use—lethargy, social deterioration and drug preoccupation that might be compared to that of the skid row alcoholic's preoccupation with drinking in the Western world. The meaning of the term is however somewhat unclear. Some have used it as a kind of blanket description to encompass a range of passivity as well as to include the behavior of numbers of young Americans who are for various reasons dropping out of school and refusing to prepare themselves for more traditional adult roles. Recently chronic American use has been associated with a type of social maladjustment resembling that reported in the foreign literature (152). Smith describes such a syndrome as "a loss of desire to work, to compete, to face challenges. Interests and major concerns of the individual become centered around marihuana and drug use becomes compulsive. The individual may drop out of school, leave work, ignore personal hygiene, experience loss of sex drive and avoid social interaction" (192).

A possible milder variation of this syndrome has recently been described by Scher in normally functioning members of the society who used marihuana for at least five years continuously throughout the day. These individuals begin to experience a vague sense that something is wrong and that they are functioning at a reduced level of efficiency (186).

The question of whether there exists a significant causal relationship between cannabis and a motivational syndrome or only an associative or correlational relationship of a person possessing these traits and cannabis use, remains to be answered.

West has described a clinical syndrome as a result of observations of regular marihuana users for 3-4 years. It is his clinical impression that many of these individuals show subtle change of personality over time. Noted are : "diminished drive, lessened ambition, decreased motivation, apathy, shortened attention span, loss of effectiveness, introversion magical thinking, derealization and depersonalization, diminished capacity to carry out complex plans or prepare realistically for the future, a peculiar fragmentation in flow of thought, habit deterioration, and a progressive loss of insight." West feels that in this configuration of symptoms a possible organic syndrome is involved (19,219).

Recently another group of investigators (71, 221) has reported tentative and preliminary data on a group of nineteen hospitalized young (14-20) patients suffering from behavior disorders. Eight of these had used only marihuana rather heavily, the other eleven marihuana in addition to other drugs such as LSD and amphetamines. Characteristically these patients showed a loss of motivation to pursue school work and other constructive activities. Other symptoms included regression to "primitive and magical modes of thought" and a low frustration tolerance. Sixteen of the group showed subtle abnormal EEG patterns particularly related to the temporal-lobes. These researchers were struck by the similarity between these abnormal brain wave findings in a group of cats administered a marihuana extract intraperitoneally. The nature of the patient group, the uncertain drug histories and the heightened likelihood of abnormal EEG tracings on other grounds all lead these investigators to interpret their work with caution. They do, however, point out that both their human and animal data tend to bear out, although not yet proven, their original clinical impression that heavy marihuana use may be an important factor in altering brain function and thus contributing to the abnormal behavior they observed. They and a number of other researchers are continuing to study the relationship of marihuana use to possible alterations in brain function.

Another possible effect of marihuana is the spontaneous recurrence without ingesting the drug of effects like those experienced when intoxicated. Such recurrent effects commonly called flashbacks have been widely reported for I,S1). While such flashbacks with marihuana have been reported (110), truly vivid experiences that recapture most of the elements of the original experience are thought to be extremely rare at least in the type of chronically using marihuana population seen in the Haight-Ashbury Medical Clinic (193). Such flashbacks may be most likely to recur following a particularly adverse drug reaction and may more closely resemble a recurrent anxiety state that the total original drug experience. Some disagreement on this point may well reflect differences of opinion as to how vivid and complete the recurrent experience must be to be termed a flashback. Many users, for example, report that new perceptual awarenesses which occurred while "high" may persist following it. If one accepts any even mild recurrence of any aspect of the drug experience without again ingesting the drug as a flashback phenomenon, that such experiences may be relatively common

Weil (216) reports the recurrence of hallucinogenic experiences during marihuana intoxication in several individuals after occasional use of LSD or mescaline These people found that their marihuana highs changed after their hallucinogenic experience, becoming benign and pleasant in some instances but disturbing in others. Unger-'eider (209) reported marihuana use recreating the LSD experience months after the LSD experience. Favazza (64) reported another case of marihuana triggering the recurrence of a frightening LSD episode. There is no way of knowing whether these LSD flashbacks would have occurred without marihuana.

REFERENCES

1. Abel, E. Marijuana and memory. Nature 227 (5263) : 1151-1152, Sept. 12, 1970.

2. Adams, R. Marihuana. Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 18: 705-730, 1942.

3. Adams, R. Marihuana. Harvey Lectures, Series 37, p. 168-197, 1941-1942.

4. Aldrich, C. K. The effect of a synthetic marihuana-like compound on musical talent as measured by the seashore test. Public Health Reports, 59: 431-433, 1944.

5. Allentuck, S. & Bowman, K. M. The psychiatric aspects of marihuana intoxication. American Journal of Psychiatry, 99: 248-251, 1942.

6. Ames, F. A clinical and metabolic study of acute intoxication with cannabis sativa and its role in the model psychoses. Journal of Mental Sciences, 104 (437) : 972-999, 1958.

7. Asuni, T. Socio-psychiatric problems of cannabis in Nigeria. UN Bulletin on Narcotics, 16 (2 ) : 17-28, 1964.

8. Baker, A. A. & Lucas, E. G. Some hospital admissions associated with cannabis. Lancet, I: 148, January 18, 1969.

9. Baker-Bates, E. T. A case of Cannabis indica intoxication. Lancet, I: 811, 1935.

10. Barbero, A. & Flores, R. Dust disease in hemp workers. Archives of Environmental Health, 14: 533-544 (1967).

11. Bartolucci, G., Fryer, L., Perris, C. & Shagass, C. Marijuana psychosis: a case report, Canadian Psychiatric Association Journal, 14: 77-79, 1969.

12. Beringer, K., et al. Zur klinik des hashischrausches. Der Nervenarzt, 5: 337-350, 1932.

13. Birch, E. C. The use of Indian hemp in the treatment of chronic chloral and chronic opium poisoning. Lancet, I: 624 (March 30, 1889).

14. Boroffka, A. Mental illness and Indian hemp in Lagos. East African Medical Journal, 43: 377-384, 1966.

15. Bose, B. C., Saill, A. Q. & Bhagwat, A. W. Observations on the pharmacological actions of cannabis Indica. Part II. Archives Internationales de Pharmacodynamie et de Therapie, 147 (1-2) : 285-290, 1964. (Biol. Abstr., 45: 95777, 1964).

10. Bouhuys, A., Barbero, A., Lindell, S. E., Roach, S. A., & Schilling, R. S. F. Byssinosis in hemp workers. Archives of Environmental Health, 14: 533- 544, 1967.

17. Bouquet, J. Cannabis. UN Bulletin on Narcotics, 2(4) : 14-30, 1950; 3(1) : 22-45, 1951.

18. Bouquet, J. Marihuana intoxication (letter). Journal of the American Medical Association, 124: 1010-1011, 1944.

19. Brill, N. 0., Crumpton, E., Frank, I. M., Hochman, J. S., Lomax, P., McGlothlin, W. H., & West, L. J. The marijuana problems; UCLA Interdepartmental Conference, Annals of Internal Medicine, 73(3) : 449-465, September 1970.

20. Bromberg, W. Marihuana, a psychiatric study. Journal of the American Medical Association, 113: 4-12, 1939.

21. Bromberg, W. Marihuana intoxication, a clinical study of cannabis sativa intoxication. American Journal of Psychiatry, XCL(2) 303-330 September 1934.

22. Brooks, W. L. A case of recurrent migraine successfully treated with cannabis indica. Indian Medical Record, II: 338, 1896.

23. Brown, J. Cannabis : A valuable remedy in menorrhagia. British Medical Journal, 1:1002, May 26, 1883.

24. Caldwell, D. F., Myers, S. A., & Domino, E. F. Effects of marihuana smoking on sensory thresholds in man. In: Efron, D., ed. Psychotomimetic drugs. New York, Raven Press, 1970, p. 299-321.

25. Caldwell, D. F., Myers, S. A., Domino, E. F. & Merriam, P. E. Auditory and visual threshold effects of marihuana in man. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 29:755-759, 1969.

26. Caldwell, D. F., Myers, S. A., Domino, E. F., & Merriam, P. E. Auditory and visual threshold effects of marihuana in man : Addendum. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 29 :922, 1969.

27. The cannabis problem : a note on the problem and the history of international action, UN Bulletin on Narcotics, 14 (4) :27-31, 1962.

28. Carakushansky, G., New, R. F., & Gardner, L. I. Lysergide and cannabis as possible teratogens in man. Lancet, 11 :150-151, January 18, 1969.