CHAPTER 1 Synthesis: national drug laws compared and contrasted

| Books - European Drug Laws |

Drug Abuse

INTRODUCTION

How do six European states use legislation as an important element in their packages of drug control? How do they compare with each other? How do their laws stand in relation to the requirements of international conventions on drugs (a key concern of the study) and European law? In other words, what is the 'room for manoeuvre' on drug laws?

This study makes enquiries in two directions: (i) 'vertically', making analytical links between national drug laws and the relevant international and European laws in order to establish the room for manoeuvre that national arrangements have in relation to international conventions and European law; (ii) 'horizontally', making comparisons between the national laws studied and providing potential comparative reference points for English drug law. These ambitions pose challenges to the study, especially in terms of expert understanding and interpretation of national laws. It is all to easy to misread the meaning of legislation in a legal and constitutional system other than one's own. Indeed, it is not always that easy within one's own system, but the hazards are multiplied when reading across legal systems. With this in mind, it was decided to commission separate studies at the national level. These could be suitably detailed and appropriately interpreted only if carried out by national legal experts. In this way, we hoped to improve the already high standard of legal research.

Previous studies

As might be expected, studies of the drug laws of European (and other) states have been undertaken in the past. Their methodologies have varied somewhat. On the basis of translated versions of national drug laws which the United Nations has been collecting for many years, in the early 1990s Bernard Leroy, a legal expert in UNDCP, produced a study of the drug laws of the then twelve members of the European Community, which was published by the European Commission. In this case, the method was scrutiny and interpretation by one person of the written laws of states. A few years later, this method was more or less replicated, although in greater depth, by a team based at the University of Ghent, in a study sponsored by the Justice and Home Affairs Task Force of the European Commission.' In 1998, a perhaps hasty and rather uneven up-date was done by officials of the EU's Council Secretariat, apparently on the basis of replies by national officials.'

All these studies have been done centrally, with an individual or team putting together a description based on written laws plus verbal or written commentaries. In the meanwhile, during 1997/8, ISDD/DrugScope conducted work in eleven EU member states which focused on administrative and civil law questions, using national legal experts to describe national laws.' This last approach has been followed here, on the basis that national experts are those best placed to do such work (as long as they adhere to a common framework of research — see below and Appendix A).5

Not only have the methods of past studies differed, so have their auspices, and that itself tells something of the backdrop to the present study. Leroy's 1991 study was published by a part of the European Commission concerned with health and drug dependence, reflecting one of the then most notably competencies of the European Community as far as drugs were concerned. By the mid-1990s, with the passage of the Maastricht Treaty, another legal basis for action had been formalised — justice and home affairs, through the third pillar of the EU. So, where Leroy in 1991 was primarily concerned with drug laws in relation to drug users, by 1995 De Ruyer et al were equally concerned with demand and supply, and moreover they included a final chapter on money laundering.

These shifting research interests correspond to some extent to the evolution of policies and structures in the European Union and internationally concerns from the 1980s onwards, focusing on drug trafficking—to which the 19886 is a witness — but also a broader concern from the 1990s onwards with organised crime.

Severity and balance: current responses

By the time we began the present study (1998), two general changes were visible.

(1) The 1980s and early 1990s bubble of political attention on drug trafficking per se became at least partly absorbed into a preoccupation with the broader topic of organised crime. Depending on one's definition of organised crime (a matter which we do not address in this study), drug trafficking plays a big or small part, and it may or may not sometimes also take place outside organised crime groups. Whatever the empirical facts may be about this linkage (organised crime/trafficking), control policies and cooperation in criminal and other laws have very definitely come to see trafficking as a matter closely linked to broader facets of organised crime.'

In this context, judicial measures against trafficking if anything stiffened further in some states, in judicial practice if not always in the written law. Whilst by the late 1990s drug trafficking as a politically galvanising category may have been getting past its 'sell by' date, its incorporation in the broader agenda on organised crime generally enhances the severity of punishment applied. In some states, a trafficker risks being sentenced for the supply offence, then for aggravating circumstances such as being involved in an organised criminal enterprise or some functionally equivalent offence carrying with it a 'top-up' sentence. Not all states apply such additional penalties but, following a EU Joint Action on criminalisation of membership of criminal organisations, the tendency seemed likely to increase. Additionally, confiscation of assets may occur (or should occur in principle, but the practice is somewhat behind the theory here).

(2) European debates on legal measures regarding drug use and possession had, by the late 1990s, moved away from the extremes seen in the 1980s and earlier 1990s. States which had hitherto been most 'tolerant', and some at least of those who had hitherto been most 'repressive', trimmed towards the centre of the control continuum. Some states relaxed aspects of law in relation to users (e.g., Germany, as regards support for locally-determined policies on prosecution for cannabis possession), whilst others tightened up (the Netherlands, on the coffee shops and related public order matters). The sometimes visceral debates between EU member states on strategies on drug users and 'drug tourism' were replaced, or at least overlaid, by a climate of enhanced administrative and criminal cooperation at the borders (France/Netherlands springs to mind). In all of this, a part was played by public awareness of HIV and AIDS and the implications for public health and social policies which could reduce those problems.

So, although by the late 1990s and especially in relation to drug suppliers, severity of repression had become firmly established as one strand in the collective response to drugs, as far as drug users are concerned, the situation is generally more nuanced. This is the policy context in which the laws reported on here have evolved and continue to evolve.

Key questions

Two key questions stand out, when viewed from the perspectives of recent history.

• Between the diverging streams of (i) international and pan-European emphasis on strong sanctions for combating drug supply in the context of organised crime and, (ii) national and European commitments to proportionality and social integration in relation to the drug user, how can the middle ground — user self-supply, possession, sharing between users, cultivation for own use, etc — be dealt with?

• How can the relative claims of national constitutional/legal arrangements, and of the international drug conventions, be reconciled?

The six states whose legal systems are examined here seem to deal with these issues in a variety of ways. Each is stimulating in its own terms. An understanding of the approach of each, of commonalities and of differences points up a number of options for future developments, discussed in the national chapters and in the conclusion of the study. For each state, a national expert was asked to make an assessment of the extent to which national existing laws are in accordance with international/EU requirements, exceed these requirements, or fall short of them. They were also asked for their assessment of any current legal debates on possible changes in any of the areas covered by the study. The following chapter synthesises their work and has been checked by them. Nevertheless, synthesis involves some collapse of legal and other categories that deserve to be understood in their own right, in the context of national constitutional and legal systems, and for that proper understanding the reader will need to refer to the national chapters.

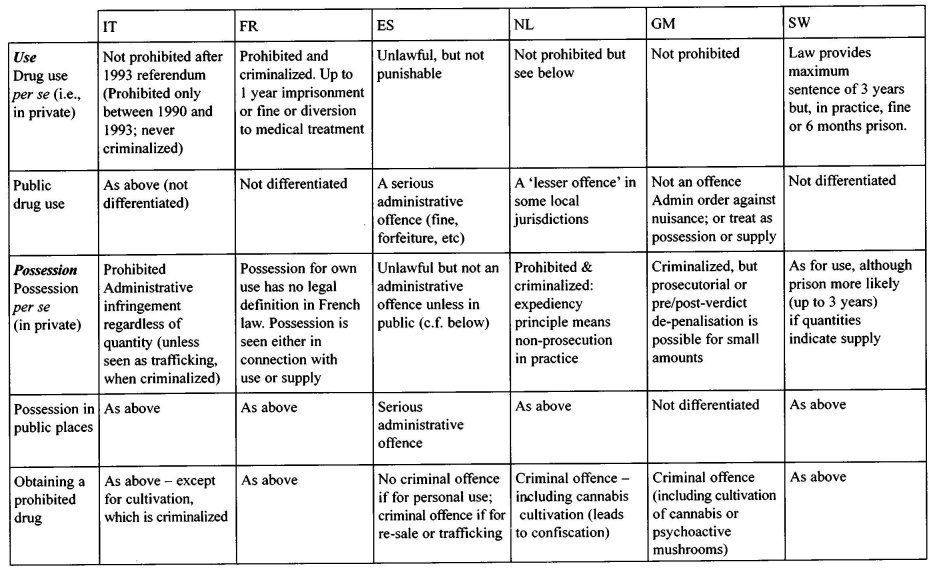

FIRST IMPRESSIONS: CONVERGENCIES AND DIVERGENCIES IN CRIMINAL LAW

The first impression is that the six states studied are rather similar in their responses to drug trafficking, whilst there is more variation in relation to the ways they respond to drug use. Based on chapters 2-7 on the legal situations in Spain, Italy, France, the Netherlands, Germany and Sweden, Table 1.1 compares national laws on drug use, possession and related matters, and supply. All six countries consider trafficking a serious offence, and prescribe long terms of imprisonment: not much difference in principle here. (But, as we shall see, maximum prison terms vary more than one might at first expect.) It is when one looks at controls on drug use and drug possession that one finds fundamental differences.

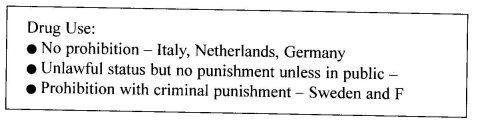

Laws on drug use (consuming drugs, being a user)

The legal status of drug use (note we are talking here of the status of the person who takes drugs) varies considerably from state to state. (For possession, see separately below.)

Three of the six countries studied prohibit drug use and the other three do not. Italy, the Netherlands and Germany do not prohibit drug use per se. Spanish law says that drug use is unlawful, but the law provides for no punishment unless it is done in public, when administrative sanctions apply.

By contrast, Sweden and France both prohibit and criminalise drug use. This means that a person may be found guilty and punished under criminal law as a result of past drug use. Obviously, possession of drugs is quite convincing evidence of drug use — unless the person concerned wishes to argue that s/he is trafficking (not an appealing course of action), or that the drugs were being held for a friend (unconvincing, and anyway might be regarded as facilitating the offence of drug use). But, as far as France goes, the significance of possession is the evidence it provides of being a drug user, this being the offence (setting aside trafficking).

Summary point

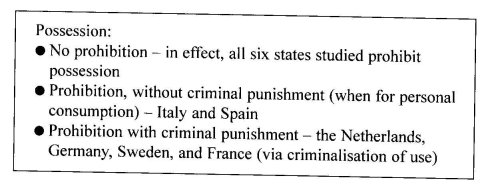

Possession: prohibition does not always equal criminalisation

When it comes to the legal status of possession per se, all countries studied prohibit it, but not all make it a criminal offence.

Here we are talking of possession rather than trafficking — e.g., possession of small amounts, or possession in circumstances which indicate that the drugs are for one's own use, or at least are not being sold on for a profit. Also bear in mind that possession generally means to have the drugs in one's hand, clothing, car, or other property, or to have effective control over them by having a key to a box containing them, etc.

In relation to possession in this sense (possession by users, normally for the purposes of own use), four of the six countries studied prohibit or do not permit or allow' it — Italy, the Netherlands, Germany and Sweden — but only the last three criminalise it. Italian law makes possession an administrative infringement only; in Spain possession for one's own use is not lawful but it is not an offence unless it occurs in public, when it attracts administrative sanctions only.

Of the six states, France is the odd one out in the sense that its law does not define possession for own use. In practice, possession is responded to as evidence either of drug use (which is criminalized), or of trafficking. So although strictly speaking it may be correct to say that French law does not prohibit or criminalise possession for own use, in effect it does both.

Summary point

Table 1.1 gives a more nuanced picture of the measures that may be applied, separately or together, on use and possession in the six states studied.

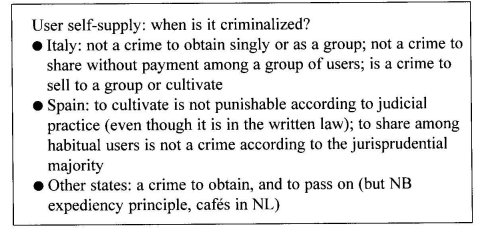

Obtaining drugs: the ground between use/possession and supply

Using a drug implies obtaining it. This can be legally problematic. Obtaining implies either the existence of another person who gives or sells the drugs (and so may be treated as a supplier), or manufacture or cultivation by the user him/herself (which in some legal systems may be treated as a supply offence). This raises a particular problem in drug law, which different national legal systems resolve in different manners.

In Spain, the case law generally does not consider it a criminal offence to obtain, by purchasing or by cultivation, a prohibited drug as long as it is not done in order to supply. Although both cultivation and purchasing are included in the scope of acts criminalized by the legislation, jurisprudence and judicial practice consider that these acts should not be punished for constitutional reasons. However, possessing it in public, which would be the case if the obtainer had to go to the point of supply, would be a 'serious administrative offence' (see chapter 2). Having obtained a drug, it is not an offence to share it out among friends or other habitual drug users if there is no danger of a wider dissemination and if the distribution is not done in public: in such cases, administrative sanctions apply but criminal sanctions do not.

In Italy, obtaining a drug has the same legal status as possessing it. In this case it is an administrative infringement, regardless of quantity (unless seen as trafficking). Furthermore, the act of giving the drug to other users, as long as done in a group, is — in certain conditions — treated in the same way. Thus current legal interpretation has it that it is not a criminal offence in Italy (i) to obtain a drug for oneself, (ii), to purchase on behalf of a group, (iii) to purchase together with a group of users or, (vi) to share out drugs between users without payment. However, cultivation for own use is criminalized, following the Constitutional Court (see Italian chapter).

In the Netherlands, possession and supply are prohibited and criminalized as envisaged in the international drug conventions. However, the expediency principle is applied in most cases of possession and in relation to supply of small quantities of cannabis through the coffee shops. The coffee shops are tolerated as long as they stick to cannabis and do not cause community nuisance problems, although their activities even in relation to cannabis are strictly speaking illegal. A similar policy applies to cultivation of cannabis in the home on a small scale, which is tolerated — as long as neighbours do not complain of the pungent smell, in which case the plants may be removed by police (as prohibited objects). In this and some other countries, heroin or substitutes for it are prescribed for dependent users as part of a treatment regime. Commentaries that refer to a decriminalisation of possession or of supply of cannabis or of other controlled drugs in the Netherlands are incorrect.

Summary point

It is clear that, with the exception of Italy and Spain (sharing among a group of users), the states studied here criminalise one or both parties to a transaction. For France, Sweden, Germany and the Netherlands, drug use/possession always implies a prior supply offence, as well as a use/possession offence. Policies on application of the criminal laws differ, as far as possession and its immediate supply are concerned, not only from state to state but also in some cases from region to region.

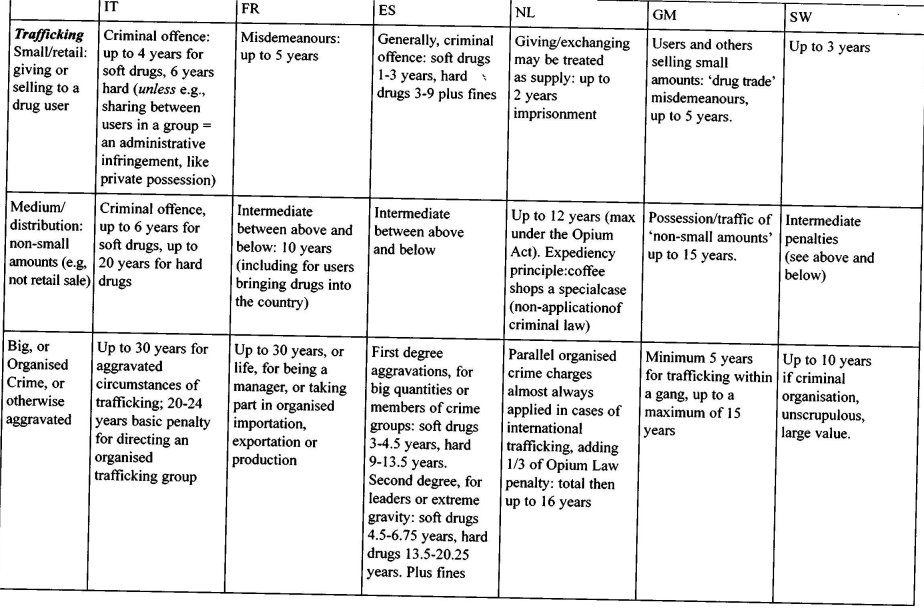

Controls on trafficking: not so convergent as they at first appear

Whatever the differences between the national control systems (and the differences are real), they share a concern which could be summed up in the sentiment, "help the users (even if we sometimes have to help them against their will), and severely punish the traffickers, who are the instigators".

As for penalties, the situation of the person found guilty of trafficking in large amounts of drugs, or of organising trafficking operations, is well known. In the more serious cases, the long maximum sentences that are provided in the laws of the various states (see Table 1.1) may be applied. There may be considerable variation depending on the circumstances of each case.

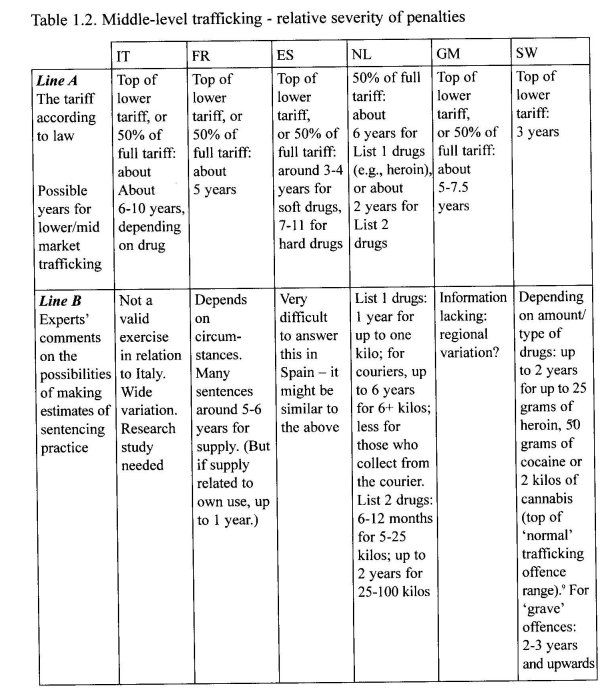

What is less clear is the position of persons found guilty of lesser trafficking offences — for example, middle-level suppliers (more serious than one instance of supply to one user, but not so serious as large-scale supply to intermediate dealers). In Table 1.2, an attempt has been made to illustrate the position of a supplier who operates in the lower-to-middle levels of the market: selling drugs at 'retail' level to a number of users, and/or selling larger amounts to other dealers who in turn sell on to users. Line A of Table 1.2 below displays, for the states in this study, some theoretical comparisons of the penalties faced by suppliers who are awarded: either the highest penalty available at the lowest end of the 'tariff' (e.g., for conviction for several retail sales); or about half the highest penalty available for distribution offences, for sale of non-small amounts (not being importation offences or organised crime). Line B of Table 1.2 presents the estimations of the national experts of the penalties in practice for such circumstances. In some cases this is based on the guidelines of the higher courts. Where this is not available, other methods of estimation have been used.

It should be stressed that these 'results' are only indicative, and that focused study in the Member States would be necessary in order to make statements with greater confidence. Nevertheless, it seems that trafficking is less severely punished in Sweden compared with the other states: perhaps because of Sweden's typically Scandinavian bias against long periods of incarceration, whatever the offence. France, the Netherlands and Germany look — on the basis of Tables 1.1 and 1.2 — to occupy the middle range in sentencing terms, as far as these mid-market offences are concerned. Italy and Spain — the two states whose laws do not criminalise drug users/possessors (not even formally) — seem relatively hard on traffickers.

It is clear that a state's legal response to drug use or possession is not predictive of its response to trafficking.

Leaving aside trafficking at the top or middle of the market, and moving to the lower reaches of the market including retail sale to, sharing between and gifts between users, differences between states become more marked.

'Health warning' for table 1.2.

Most of the experts are unsure of the value to this exercise and one at least believes it is useless. This is partly because the extent to which courts follow guidelines or otherwise arrive at a degree of sentencing consistency varies from legal system to legal system; in some systems, specific aspects of the case may carry considerable weight in sentencing (e.g., Italy), in others the response is generally more formulaic (e.g., possibly Sweden). It should be noted that consistency is not always held to be an ideal. More work and in some cases close empirical study would be needed to go further.

All states prohibit and criminalise trafficking in the narrow sense — the business of selling large amounts of drugs such as heroin (outside certain permitted categories, e.g. for medical purposes). Most states go further, extending the category of trafficking to include cultivation for personal use; one state does so as far its legislation is concerned but not in the majority jurisprudential opinion and practice (Spain). The position of cannabis in the Netherlands is well known (see above and chapter 4). Obviously, in practice, toleration of the coffee shops and of home cultivation may lead to the supply of others (who get cannabis from the coffee shop purchaser or home cultivator).

Also noteworthy is the situation in Italy, where users who obtain drugs together with others in a group commit an administrative infringement, but not an offence; however purchase by one individual who then re-sells drugs to the rest of the group constitutes a penal offence because in that case, from the point of view of Italian law, a transfer (as distinct from sharing) is involved. Also, someone who cultivates for their own use is liable to face criminal sanctions under current legal interpretation.

Thus, in practice, enforcement agencies in three states out of the six studied are able not to proceed criminally against some aspects of small scale supply: Spain in relation to cultivation of cannabis for personal use and gifts of drugs among users, the Netherlands in relation to cannabis sold in a limited number of commercial outlets, and Italy in relation to users sharing (not selling) a drug with other users in a group. These exceptions aside, in practice as well as in law, all states criminalize the supply of drugs.

Summary point

Trafficking

• All states prohibit major and mid-market drug supply, criminalise it and provide long imprisonment terms.

• But in relation to supply to users, Italian and Spanish jurisprudence makes sharing in a group (all drugs) non-punishable. The Spanish jurisprudence makes cultivation for own use (cannabis) non-punishable. The Netherlands criminalizes retail sale and home cultivation of cannabis but generally does not prosecute.

SECOND IMPRESSIONS:

BREAKING THROUGH THE CRIMINAL/NON-CRIMINAL DICHOTOMY

Variety of controls on possession/use

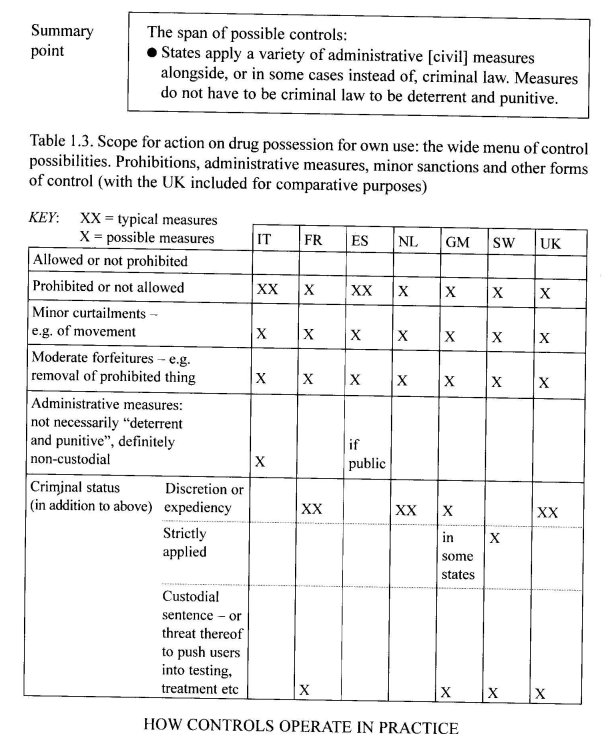

For the majority of states, regulation and prohibition is not simply a matter of criminal law or not, criminal action or not. Most legal systems provide for a variety of 'intermediate' forms of control.

These may be thought of as standing in between laissez faire and criminalization: a range of administrative measures, and administrative sanctions (either noncriminal or quasi-criminal). For the purposes of this Introduction, these measures include what are generally called 'civil' measures in common law countries such as Britain and Ireland, including civil fines and civil confiscation.

Such measures/sanctions — which generally derive from the wider features and national traditions of constitutions and legal systems — are sometimes applicable to drug use, possession and related activities (sharing drugs with other users, for example, or using drugs in public).

It would be wrong in principle to think that all administrative measures are necessarily 'gentler' or 'softer' in their impact than criminal measures. It all depends on the measure concerned, and its impact in particular cases.' Sometimes, an administrative measure can be more severe than a criminal measure, even in the face of no determination on the question of 'guilt'. For example an administrative fine or confiscation could be very high: administrative/civil confiscation in some states can, effectively, be total, at least in its intent. A bar on practising a profession or trade can have considerable impact. However, such high levels of impact of administrative measures are relatively uncommon and are generally restricted to cases of drug supply (and other serious or organised crime cases). The relationship between such measures and criminal law varies in different legal systems: they may apply within criminal law, or alongside criminal law (as an adjunct), or as an alternative to action under criminal law.

When it comes to drug users/possessors, administrative measures are generally less severe than criminal sanctions, both in terms of the impact they are intended to have and in their practical consequences for the user/possessor. Such measures range from restrictions on movement (for a day, or for longer), to withdrawal of licences to drive, to run a particular business establishment, or to practice a profession. Other measures, having no impact other than the forfeiture of the thing that is prohibited under law — drugs, paraphernalia such as pipes, injection equipment — may fall under administrative or criminal law, or under both, varying from state to state. For the purposes of this introductory description, they are described as 'curtailments — minor administrative measures — regardless of their strict legal definition (which is given in the national chapters). Table 1.3 summarises the range of such measures applicable to drug possession for personal use. Please refer to the national chapters for details.

Evaluation of the impact and cost-effectiveness of administrative measures is generally lacking (as is evaluation of the impact and cost-effectiveness of criminal law). However, it is clear that public policy does not face a straight choice between either criminalisation or laissez faire. There is a large intermediate canvas of control measures — varying from prohibition backed up by exhortation, through administrative measures that may be annoying and/or inconvenient for the person affected, to administrative sanctions which may have considerable 'bite' — which may be applicable to drug possession and related acts.

Although it is not difficult to describe the written laws on drug use and possession, it is more difficult to make meaningful comparisons of what happens in practice. There are at least two sources of difficulty.

Variations in practice under criminal law, where applicable

As far as criminal law measures are concerned, in practice many (but not all) of the systems under study here respond with a range of forms of discretion, arbitrariness, flexibility, expediency, etc — especially as far as drug use, possession and related acts are concerned.

In some states, there is no overarching principle favouring either prosecution or non-prosecution for drug possession. The authorities weigh up the circumstances of each case, in the light of guidelines, and with some variations from one part of the country to another. In Germany, the prosecutor or the court may decide, on a case by case basis, whether to de-penalise the case: if so, then conditions may or may not involve attendance at a helping agency. German practice varies between the Lander, with something of a north/south split, and, during the late 1990s when this was written, might be entering a period of change. In such countries, it is particularly difficult to make general statements about what happens in practice. (Perhaps the UK also falls into this category as far as possession is concerned.)

In other states, a strict legality principle applies, at least theoretically, and the presumption is in favour of prosecution. In Sweden, the prosecutor must prosecute if there are 'sufficient reasons for doing so' (see chapter 7 below). There are far-reaching legal exceptions, which might result in some or many possession cases not being prosecuted. For example, a decision not to proceed with some charges may be made if the prosecution decides that there are other suitable charges. Of course, the extent to which even such limited action occurs, depends somewhat on the broader climate regarding drug control. With respect to the restrictive Swedish policy, discretion in practice is quite limited, particularly in relation to narcotic drugs. By comparison France, noted during the 1980s and much of the 1990s for its vigorous pursuit of drug possessors suspected of minor drug Lrafficking (French law having no legal category corresponding to possession per se), began to moderate this practice from the late 1990s onwards.

Thus, the presumptions in favour of prosecution that may be made by reference to the formal features of national legal systems may or may not be a guide to what actually happens. So, even in strict liability systems (if we can call them that) it can be difficult to make general statements about practice.

In other states, an overarching principle favouring non-prosecution may be built in as a formal part of the system. The famous Dutch 'expediency principle', for example, involves a direction to the prosecuting authorities not to press charges against drug possessors of small amounts, but to encourage those who seem to need it to seek health assistance. This means that drug possession per se is generally not a factor increasing the likelihood of entry into the criminal justice system." In exceptional cases, of course, a case of drug possession could be prosecuted. And drug-related crimes are likely to be prosecuted: for example, crimes such as burglary, fraud, other property crimes and crimes of violence would generally be prosecuted, irrespective of the drug-using or non-using status of the person who commits them. Any diversion to treatment is likely to rely on the criminal law to motivate the person to accept treatment 'or else'. In such states, where the presumption is on non-prosecution for possession per se, we can be relatively certain of the general pattern of prosecution in practice. However, this is not the situation in the majority of states in which possession is criminalized.

Variations in practice under administrative laws

In the absence of a corpus of pan-European research on this question, we cannot say whether administrative measures on use and possession (other than for supply) are applied more or less vigorously and less frequently than more punitive measures relating to supply.

Any expectation that administrative measures may fall into disuse appear not to be borne out by experience. It is reported from those countries in which neither use nor possession is punishable under criminal law — Italy and Spain — yet administrative measures which are applicable at least to some aspects of use/possession, that such measures are vigorously applied in practice.' For example, in Italy between 1990 and 1997 administrative sanctions for personal use were applied 220,680 times. In Spain, fines are commonly applied, which leads to difficulties in those cases in which the person has no money.

In summary, as far as users are concerned, in neither Italy nor Spain is there any indication that administrative measures are applied less vigorously than criminal measures might have been in similar circumstances.

Might there even be a tendency for administrative measures to be applied more vigorously against drug users in those states in which they are applicable, compared with the application of the law in states such as France and Sweden which punish use and/or possession under criminal law? Whilst this is a possibility, as far as this study is concerned it remains speculation, due to the limitations of the study. It may well be that the keenness of the police and prosecution authorities varies from time to time, as well as from state to state. When numbers of drug users are small and the climate more restrictive, then police may have a greater tendency to arrest them. But when the numbers of possible arrestees are large, and if the climate less restrictive, police may be less likely in practice to proceed against users/possessors. Whatever the formal position may be regarding the obligation of the national or local police to respond to every infringement, including minor ones, in reality enforcement practitioners tend to try to use their time to best effect, in order to suppress or prevent those acts which are regarded as most serious. This means that they focus upon criminal actions which attract at least middle-range sanctions. However, as already noted, any such tendencies to selective targeting are likely to be mediated by the national, regional or local political climate.

Summary point Possession/use in a public place, in practice (tentatively):

• No action likely in the Netherlands

• Administrative enforcement occurs: Italy and Spain

• Variable responses under criminal law: Germany

• Criminal law-based action likely: France and Sweden

Administrative controls on trafficking

Even though the rhetoric of condemnation is pitched higher in criminal law, and even though very long prison sentences can be imposed in all the states studied (indeed, virtually all states), nevertheless administrative measures in relation to supply can have considerable bite.

This potential bite is extended to a wider range of targets because administrative measures can generally be applied on the basis of a lower level of evidence — and sometimes on suspicion. And recent developments in the national laws of some states suggest that, in future, more emphasis will be placed on what are in effect administrative measures against trafficking, for example confiscation of assets of those suspected of crime," and possibly confiscation of property of those found to be 'a member' of a criminal organisation, i.e. a group or enterprise in which others are acting criminally.

In chapter 8 we will turn to the question of the correspondence (and occasional lack of correspondence) between, on the one hand, the theory and practice of national drug legislation and, on the other hand, the three international drug conventions. In chapter 9 we discuss what the implications of these facts and the dynamics that underlie them may be for good policy making. And in chapter 10 we make some propositions for development of law in the UK. First, however, the national authors present pictures of the situations in the six states studied.

1' Leroy, B, 1991, The Community of Twelve and the Drug Demand: comparative study of legislation and judicial practice, Luxembourg: Commission of the European Community, Directorate general of Employment, Industrial Relations and Social Affairs, Doc CEC/LUXN/E/1/28/91, pp 82. See also Cornil, L, 1996, Les drogues de l' Union Européene: le droit en question, Bruxelles: Editions Bruyant.

2 De Ruyver, B, 1995, Drug Policy in the European Union: possibilities offered by Article K.1(4) of the European Treaty, Ghent: University of Ghent, Research Group Drug Policy, pp 96.

3 EU, 1998, Updated Version of the Comparative Study on Drug Legislation in Europe, pp 23 within Annex III of Report on Drugs and Drug-related Issues to the Vienna European Council, Doc 12334/1/98 Rev 1, CORDROGUE 65, Brussels: The Council.

4 Dorn, N (ed), 1999, Regulating European Drug Problems, The Hague: Kluwer. This was financially supported by the European Commission (drugs coordination unit), but on the basis of an approach to the Commission rather than by the latter's initiative.

5 A similar approach was later followed when the European Monitoring Centre on Drugs and Drug Addiction commissioned research on behalf of the EU on prosecution — albeit restricted to prosecution of drug users — 'Study on prosecution of drug users', EMCDDA, contracted to DrugScope with the University of Ghent and national experts in EU Member States.

6 United Nations Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances, 1988, done at Vienna on 20 December.

7' Dorn, N, 1999, 'Du renseignement au partage des informations: l'intelligence protéiforme', Les Cahiers de la Sécurité Intérieure, no.34, pp 91-108.

8 The terms 'prohibit', 'permit' and 'allow' can have specific meanings under national laws. Here the terms are used in a general and descriptive sense — which may be legally imprecise in some cases. For specific definitions, please see the national chapters. Please note that, as used here, the word 'prohibit' does not necessarily imply punishment whether under criminal law or otherwise.

9 Summarised by ND from remarks offered by Josef Zila, based on the unofficial guide, Studies on Sentencing Practice: Sterzel, G, 1998, Studier rikande peciljdspraxix m. m., Stockholm.

10 "As recognised by the European Court of Human Rights which, through its case law, requires the judicial or administrative procedures for measures that have a 'deterrent and punitive' effect on the person or entity to which they are applied to offer to the person the same procedural guarantee as in a criminal trial. Note that one and the same administrative measure may have quite different impacts on different persons, so generalisations are hazardous.

11 The British situation would be rather different, in that police are encouraged to respond to all the circumstances of every situation: although the majority of possessors are not prosecuted (at least, not for cannabis), the outcome of an encounter between police and a drug possessor is less predicable in Britain than in the Netherlands (especially if a Class A drug such as Ecstasy or heroin is involved).

1'2 Source: written communications from national authors, April 1999.

13 Home Office Organised and International Crime Directorate, Home Office Working Group on Confiscation Third Report: Criminal Assets, November 1998.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|