| Reports - Effect of Drug Law Enforcement |

Drug Abuse

DISCUSSION

Summary of Evidence

In this systematic review, all available English language studies that evaluated the association between drug law enforcement and violence were reviewed. Though limited in number, they employed a diverse array of methodologies, including longitudinal analyses involving up to six years of prospective follow-up, multilevel regression analyses, qualitative analyses, and mathematical predictive models. Contrary to our primary hypothesis, among studies that employed statistical analyses of real world data, 82% found a significant positive association between drug law enforcement and violence.

Discussion

The present systematic review suggests that drug law enforcement interventions are unlikely to reduce drug-related violence. Instead, and contrary to the conventional wisdom that increasing drug law enforcement will reduce violence, the existing scientific evidence strongly suggests that drug prohibition likely contributes to drug market violence and higher homicide rates. On the basis of these findings, it is reasonable to infer that increasingly sophisticated methods of disrupting

drug distribution networks may increase levels of drug-related violence.

The association between increased drug law enforcement funding and drug market violence may seem counter-intuitive. However, in many of the studies reviewed here, experts delineated certain causative mechanisms that may explain this association. Specifically, research has shown that by removing key players from the lucrative illegal drug market, drug law enforcement may have the perverse effect of creating significant financial incentives for other individuals to fill this vacuum by entering the market.33, 34

“Prohibition creates violence because it drives the drug market underground. This means buyers and sellers cannot resolve their disputes with lawsuits, arbitration or advertising, so they resort to violence instead.”

Jeffrey Miron Harvard Economist

These findings are consistent with historical examples such as the steep increases in gun-related homicides that emerged under alcohol prohibition in the United States 37 and after the removal of Columbia’s Cali and Medellin cartels in the 1990s. In this second instance, the destruction of the cartels’ cocaine duopoly was followed by the emergence of a fractured network of smaller cocaine-trafficking cartels that increasingly used violence to protect and increase their market share. 37 Violence may be a natural consequence of drug prohibition when groups compete for massive profits without recourse to formal, non-violent negotiation and dispute resolution mechanisms .24, 25

An Afghan police officer stands guard in poppy fields during a poppy eradication campaign in the Rhodat district of Nangarhar province, east of Kabul, Afghanistan, on April 11, 2007. Afghanistan produced dramatically more opium in 2006, increasing its yield by roughly 49% from a year earlier and pushing global opium production to a new record high, according to a UN report. (AP photo / Musadeq Sadeq)

“Prohibitionist policies based on eradication, interdiction and criminalization of consumption simply haven’t worked. Violence and the organized crime associated with the narcotics trade remain critical problems in our countries. Latin America remains the world’s largest exporter of cocaine and cannabis, and is fast becoming a major supplier of opium and heroin. Today, we are further than ever from the goal of eradicating drugs.”

Fernando Henrique Cardoso, Former President of Brazil César Gavira, Former President of Colombia Ernesto Zedillo, Former President of Mexico

While not a central focus of this review, prior reviews have concluded that, in addition to violence, drug prohibition has produced several other unintended consequences. One key concern driving the introduction of new players into the illicit drug market is the existence of a massive illicit market that has resulted in response to the prohibition of illicit drugs, estimated by the United Nations to be worth as much as US$320 billion annually.38 These enormous drug profits are entirely outside the control of governments and, based on the findings of the present review, likely fuel crime, violence, and corruption in countless urban communities. Further, these profits have destabilized entire countries, such as Colombia, Mexico, and Afghanistan, and have contributed to serious instability in West Africa.39-42 In North America, profits from the marijuana trade constitute a major source of potential corruption and instability. In British Columbia, Canada, the marijuana market was recently estimated to be worth approximately C$7 billion annually,43 and recently a ferocious gang war has been waged over the control of these profits, which are largely derived from exporting the drug to the United States. 12, 44 In the United States, cocaine is used at least annually by approximately 5.8 million people, and control of this market has long been characterized by gang violence.1, 5, 6, 45 In southeast Asia, a burgeoning illicit methamphetamine trade is intimately tied to regional instability, where the minority Wa and Shan groups fund an insurgency against Burma’s military junta through manufacture and wholesale distribution of methamphetamine and opium to Thailand, China, and other neighbouring countries .46 In West Africa, entire countries such as Guinea-Bissau are at risk of becoming “narco-states,” as Colombian cocaine traffickers employ West African trade routes to distribute cocaine into destination markets in Europe, Russia, and the Middle East .42 Estimates now suggest that 27% of all cocaine destined for Europe is transited through West Africa and is worth more than US $1.8 billion annually wholesale and as much as ten times that amount at the retail level.42

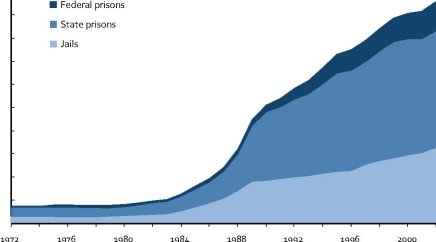

In terms of additional unintended consequences, in the United States, mandatory minimum sentencing policies for drug offenders have resulted in a massive growth in the prison population and place an enormous burden on the US taxpayer .47, 48 Figure 3 illustrates the dramatic rise in incarceration rates following the implementation of mandatory sentencing policies by many American states beginning in the 1980s. Most notably, the incarceration of drug offenders in the United States has generated substantial racial disparities in incarceration rates. 49-52 For instance, one in nine African-American males between the ages of 20 and 34 is incarcerated on any given day in the United States .53

Royal Canadian Mounted Police Sgt. Daniel Quirion of the Integrated Proceeds of Crime unit looks over marijuana plants in the basement of a Moncton house in the Royal Oaks area on July 27, 2004. The RCMP executed search warrants at 14 homes in the greater Moncton, New Brunswick area as part of an organized crime investigation into commercial marijuana grow operations. (CP photo / Moncton Times & Transcript – Viktor Pivovarov)

Figure 3. Estimated number of adults incarcerated for drug law violations in the united States, 1972–2002

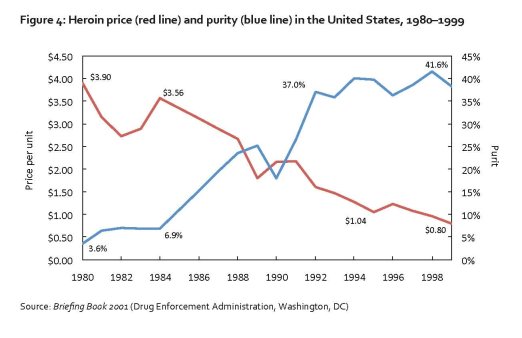

While the unintended consequence of increased drug-related violence might be acceptable to the general public under the scenario whereby drug law enforcement substantially reduces the flow of illegal drugs, prior research suggests that law enforcement efforts have not achieved a meaningful reduction in drug supply or use in settings where demand remains high .54 In the United States, despite annual federal drug law enforcement budgets of approximately US$15 billion and higher since the 1990s, illegal drugs— including heroin, cocaine, and cannabis—have become cheaper and drug purity has increased, while rates of use have not markedly changed .21, 55, 56 Figure 4 shows the startling increase in heroin purity in the US from 1980 to 1999 against the equally startling drop in price over the same period. In Russia, despite a strong emphasis on drug law enforcement, evidence suggests that illicit drug use is widespread. 45 Specifically, recent United Nations estimates suggest that more than 1.6 million Russians use illicit opiates annually, though experts caution that the true number could be as high as 5 million .45

In the face of strong evidence that drug law enforcement has failed to achieve its stated objectives and instead appears to contribute to drug market violence ,24, 25, 56 policy makers must consider alternatives. Indeed, some experts have begun to call for the regulation of illicit drugs. In the United Kingdom, a drug policy think tank which recognized the link between drug prohibition and violence has recently released a report delineating potential regulatory models for currently illegal drugs .57 In California, recognition of the linkages between drug demand in the US and violence in Mexico, as well as the recent fiscal deficit, has prompted the State Board of Equalization to prepare estimates of the potential revenue from a regulated marijuana market .58 The State Board estimated that annual revenues of approximately US$1.4 billion could result from the imposition of a regulatory framework .58 Additionally, recent results from an evaluation of Portugal’s drug decriminalization policy suggests that this approach may reduce both illicit drug use and its related harms.59

While it is outside the scope of this report either to support or oppose these proposals, given the apparent link between violence and the existing model of drug prohibition, these alternative regulatory models should be the subject of further study.

Authorities seized weapons and an estimated US$207 million in a raid on a luxurious Mexico City home in March 2007. At the time, the US government called it “the largest single drug cash seizure the world has ever seen.” (Procuraduria General de la Republica)

Limitations

This study has a number of limitations. Most importantly, publication bias may have skewed the availability of studies investigating the role of violence and drug law enforcement as a result of political sensitivities in organizations funding research on drug policy. Specifically, research sponsors traditionally have been unsympathetic to funding research critical of drug prohibition.60, 61

There are also instances, such as the recent outbreak of violence in Mexico, where there is widespread agreement that law enforcement efforts sparked drug market clashes, but this phenomenon does not get reported in the context of a scientific study.

In terms of potentially underestimating violence, the present analysis was restricted to only those studies investigating the effect of drug law enforcement on drug market violence; studies that reported only on police violence or on violence generated by insurgencies financed by the drug trade were excluded.

For the above reasons, the positive association between drug law enforcement and violence that we identified in the literature is most likely an underestimate.

The findings of this report do not imply that individual police officers are responsible for this violence. Rather, the evidence suggests that front line police officers are given the task of enforcing drug laws that appear to lead to increased violence by unintentionally driving up the enormous black market profits attributable to the illegal drug trade.

“The prestige of government has undoubtedly been lowered considerably by the Prohibition law. For nothing is more destructive of respect for the government and the law of the land than passing laws which cannot be enforced. It is an open secret that the dangerous increase of crime in this country is closely connected with this.”

Albert Einstein

Conclusions

Based on the available English language scientific evidence, the results of this systematic review suggest that an increase in drug law enforcement interventions to disrupt drug markets is unlikely to reduce violence attributable to drug gangs. Instead, from an evidence-based public policy perspective and based on several decades of available data, the existing evidence strongly suggests that drug law enforcement contributes to gun violence and high homicide rates and that increasingly sophisticated methods of disrupting organizations involved in drug distribution could unintentionally increase violence. In this context, and since drug prohibition has not achieved its stated goal of reducing drug supply, alternative models for drug control may need to be considered if drug-related violence is to be meaningfully reduced.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|