3. Research Methodology and Data

| Books - Drug, Set, and Setting |

Drug Abuse

3. Research Methodology and Data

IN 1972, WHEN I BEGAN SEEKING FINANCIAL SUPPORT FOR RESEARCH ON controlled illicit drug use, the scarcity of previous research in the area was a liability rather than an asset. Although chances for funding were increased by the promise that my study would contribute new information about intoxicant use and misuse, there was virtually no direct evidence-other than Douglas H. Powell's study of twelve occasional heroin users (1973)-that cooperative and suitable subjects, particularly controlled users of the opiates, could be located efficiently or that they would be willing to reveal the details of their personal lives and illicit activities. Lack of tested approaches to this population raised the same kinds of difficult and fundamental questions that many other pilot and exploratory studies have had to contend with: How can controlled users be recruited? What kinds of information about controlled users are critical? What instruments or approaches should be used to collect data? Can it be reasonably expected that the data will be reliable and valid? In addition to these meth odological uncertainties, it was likely that a project designed to consider the existence of controlled users would be heavily criticized by those who felt that this sort of study would hurt the cause of drug-abuse prevention.

Much credit is due The Drug Abuse Council (DAC) for its willingness to invest in this basic exploratory research despite the expected uncertainties and inefficiencies as well as the likelihood of public and professional disapproval. Initial funding by the DAC afforded the opportunity to test and refine research methods for the study of controlled use and to develop a clearer conceptual model of this style of use.

Methodology

The DAC study was exploratory and tentative. It had four rather modest goals: (1) developing appropriate means for locating controlled marihuana, psychedelic, and opiate users; (2) developing and applying means for gathering and, if possible, validating data from these users; (3) providing a description of the subjects, their personality structures, and their drug-using patterns; and (4) beginning to identify factors that might stabilize or destabilize controlled use.

The use of the term "controlled use" rather than "occasional use" in formulating these goals reflected my interest in understanding how controlled-that is, how successful and consistent-such occasional drug use could be, and thus how the potential harm of drug use could be minimized. Accordingly, several broad criteria for selecting subjects were developed to maximize the chance of finding subjects who were moderate and careful about their drug use. The most obvious requirement was that candidates should not be such frequent users that their use would interfere with family life, friendships, work or school, and health. The problem was to estimate what level of use might be reasonably expected to have adverse effects. Multiple daily use and daily use were ruled out immediately-not because it was certain that such use was always destructive but because, as Jaffe ( 1975) has pointed out, "the greater the involvement with drugs, the more likely adverse consequences. " I also felt that whatever the behavioral evidence might be, there was little chance of convincing others that daily use, especially daily opiate use, could be controlled.

Although no further or more explicit cut-off points for frequency were established, the research team attempted to be conservative: we recruited subjects who had used once a week or less for at least one year prior to the initial interview. (Some candidates who had used more frequently slipped through our initial screening, however, and later we deliberately sought out more frequent users in an attempt to learn how useful frequency alone was as an indicator of control.)

In the DAC pilot project, the conditions for subject selection were rather general; they were also subject to periodic revision as interviews progressed and data were coded and analyzed. At all times the study was conceptualized as both qualitative and quantitative. Data were collected in such a way as to permit the construction of detailed case histories and the selection of excerpts from these histories that would give verisimilitude to the study and allow other researchers to compare our findings with their own experience. As the study progressed, data were coded, computerized, and statistically treated to determine quantitive significance.

In 1976 the accomplishment of the goals I had set for the pilot project led to the funding of my research by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). Based on knowledge gained from the earlier project, the study team was able to settle on the following detailed, precise definitions of our subjects: "controlled," "marginal," and "compulsive."

Conditions for All Subjects

1. They must be at least eighteen years of age.

2. They must have no definite plans to move out of the Metropolitan Boston area within the next year.

3. They must first have used an opiate two or more years ago.

4. They must not have been in treatment for more than one month during the two years preceding their initial interview and cannot be in treatment at the time of the initial interview.

Conditions for Controlled Subjects

1. They must have used an opiate' at least ten times in each of the two :" years preceding admittance. If they did not fulfill this condition for one of the two years preceding admittance, they must have used an opiate within the last year and must also have met conditions 1, 2, 3, and 4 in at least two consecutive years of the preceding four.

2. In each of the two years preceding admittance they must not have had more than three periods of four to fifteen consecutive days of opiate use.

3. In those preceding two years the number of days of opiate use in any thirty-day period might have equaled but must not have exceeded the number of abstaining days.

4. In those preceding two years they must have been using all drugs (licit and illicit, except tobacco) in a controlled way.

Conditions for Marginal Subjects

1. They must have used an opiate at least ten times in each of the two years _ preceding admittance. If they did not fulfill this condition in one of the two years preceding admittance, then they must have used an opiate within the last year and must also have met conditions 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 in at least two consecutive years of the preceding four.

2. In at least one of the preceding two years, they must have had at least four periods of four to fifteen consecutive days of opiate use; or at any time in those two years they must have had at least one thirty-day period in which the number of using days exceeded the number of abstaining days.

3. In each of the preceding two years, they must not have had more than '' five periods of four to fifteen consecutive days of opiate use. (Periods of more than fifteen consecutive days of opiate use were counted differently: see conditions 4 and 5.)

4. In each of those preceding two years, they must not have had more than two thirty-day periods in which the number of using days exceeded the number of abstaining days.

5. In each of those preceding two years, they must not have had more than one period of sixteen to thirty consecutive days of opiate use.

Conditions for Compulsive Subjects

1. They must have had at least six periods of four to fifteen consecutive days of opiate use in at least one of the two years preceding admittance.

2. If they did not fulfill condition 1 or 3, then in at least one of the two years preceding admittance they must have had at least three thirty-day periods in which the number of using days exceeded the number of abstaining days.

3 . If they did not fulfill condition 1 or 2, then in at least one of the two years preceding admittance they must have had at least two periods of sixteen to thirty consecutive days of opiate use. (Thirty-one or more consecutive days of opiate use automatically made them compulsive users.)

All candidates recruited who did not meet one of these four sets of criteria were assigned to a fourth category, "other."

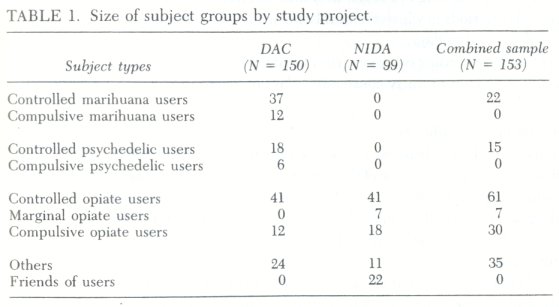

As these criteria indicate, the definition of "control" used in the NIDA study had none of the judgmental fuzziness that had characterized the DAC study. Instead, the question of how differences in current functioning (and other characteristics) related to level of use was determined empirically by comparing subjects who had been grouped by frequency of use alone. Unlike the DAC pilot study, where, originally by accident and later by intention, some compulsive users of marihuana, psychedelics, and opiates had been recruited and interviewed (see table 1), the NIDA study had as its major research goal the comparison of controlled and compulsive opiate-using subjects. In order to achieve this goal, our limited resources were applied exclusively to opiate users, and further study of marihuana and psychedelic users was dropped. This decision was made partly because the notion that marihuana use could be controlled had become more widely accepted in the American culture, and partly because, even though the possibility of controlled psychedelic use was scarcely recognized, the research team had found no truly longterm compulsive psychedelic users among the six heavy users they had studied. It seemed, therefore, that in order to determine whether the use of any drug could be controlled, it would be best to focus on the opiates.

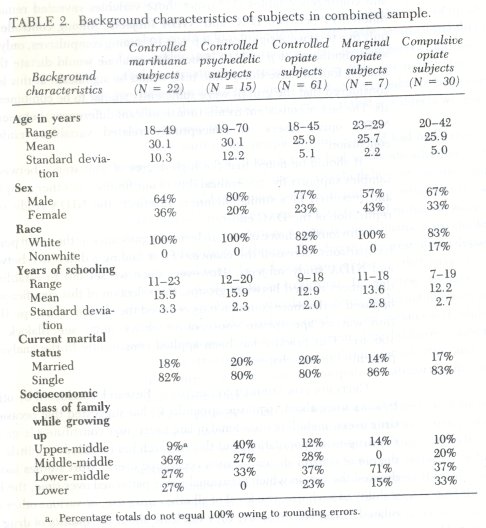

In sum, my investigation of the controlled use of illicit drugs shifted in 1976 from the use of general definitions to the use of more specific and objective definitions of drug-using categories, and from a concern with marihuana, psychedelics, and opiates to a concentration on opiate use. Moreover, the study team and I began to make a selection of DAC and NIDA subjects that we called the Combined DAC-NIDA Analytical Sample. The statistical data cited throughout this book are drawn from this sample unless otherwise indicated. The numbers and types of subjects in the DAC project, the NIDA project, and the combined sample are presented in table 1, and the background characteristics of those in the combined sample are shown in table 2.

Candidates chosen for the sample were required to fulfill all the subjectselection criteria developed for the NIDA study. In the case of opiate users, the analytical sample combined those DAC subjects (twenty out of forty-one controlled opiate users and twelve compulsive users) who met the more stringent and objective conditions developed under the NIDA grant with forty-one controlled NIDA opiate users and eighteen compulsive NIDA opiate subjects. The DAC users of marihuana and psychedelics who met the NIDA definitions were also included in the sample, but the fifteen controlled marihuana users and the three controlled psychedelic subjects who did not meet these criteria were excluded from all of our statistical computations. The most common reason for excluding DAC subjects from the analytical sample was that they lacked the longer period of controlled use required by the NIDA guideline: at least two years as against the pilot project's one year.

The net effect of this procedure was, of course, to reduce the size of the analytical sample drastically. This reduction was unfortunate in away, but I felt very strongly that the most conservative and demanding definitions of controlled and compulsive subjects-the cleanest sample-should be used to quantify the data. And even though the number of subjects used for quantitative analysis was limited, the project personnel conducted numerous screening interviews and held regular consultations with all sorts of users, addicts in treatment, and their families and friends, which supplied valuable information for the qualitative side of the project.

Since the analytical sample consists of controlled and compulsive opiate users drawn from two studies that, however similar, were conducted at different times, steps were taken to assess the comparability of these subjects. First, the controlled opiate subjects and the compulsive opiate subjects from both studies were compared on thirty-nine key variables chosen from several topic areas: demographic, personality, family history, history of drug use, current drug use, and past and present criminal activity. Results from thirty-nine t-tests and contingency tables (X 2) using those variables revealed remarkably few differences between DAC and NIDA subjects. Among controlled subjects, only five tests were significant at p ≤ 0.10. among compulsives, only three tests were significant at p ≤ 0.10. Since chance alone would dictate that approximately four of these thirty-nine tests would be significant at this level, it was considered that the groups were sufficiently similar to be combined for analysis. The lack of consistent trends (nonsignificant differences) between DAC and NIDA opiate users on conceptually related variables reinforced thisconclusion.

It should be noted that the high degree of consistency between the twosamples supports the generalizability of our findings to other samples defined and recruited in a similar manner. In effect, the NIDA study served as < replication of the DAC effort.

Obviously, choice of an 0.10 level of significance as the cutoff point in these comparisons increased the chances of our finding a difference between DAC and NIDA study subjects. However, since we set out to establish that no differences existed between groups, the selection of this significance level as opposed to the more common 0.05 reduced the chances of a Type II error and thus was an appropriate conservative choice (e.g ., see Blalock 1979, pp 16o-61). This practice has been applied consistently to the analyses of data presented in this chapter.

CRITERIA FOR SUBJECT SELECTION. Research conducted by other inves tigators since about 1970 (see appendix C) has suggested that occasional illicit drug users, including occasional opiate users, may constitute a large portion o the drug-using population, but this research has revealed very little about the degree of control shown by such occasional users. Most studies have not ad dressed the way in which occasional use is patterned over time, the long-term stability of such use, the level of all other drug use, or various other questions related to control. In short, they tell little about the quality of drug use.

It was because of these shortcomings that my study team formulated the set of conditions listed earlier for selecting subjects for the Combined DAC NIDA Analytical Sample. Each criterion was chosen for a specific reason. The requirement that all candidates should be at least eighteen years old grew out o our experience during the DAC study, when we had held informal interviews with twenty-one adolescents under eighteen in order to learn something about early using patterns. Drug use among this age group seemed too volatile to warrant the inclusion of younger subjects in either the final DAC sample or the NIDA sample. The purpose of requiring that subjects not have definite plans to move out of the Metropolitan Boston area during the year following their initial interview was, obviously, to maximize the chances for follow-up. The rule that subjects must have first used marihuana, psychedelics, or opiates two or more years before their first interview ensured some minimal stability in the patterns of use under study. The requirement that subjects could not have been enrolled in a treatment program for more than one month during the two years preceding the initial interview, and that they could not be in such a program at the time of the initial interview, ensured that all subjects were active drug users in the community.

Since most of the people we interviewed had had experience with more than one drug, the research team had to decide whether to treat each such multiple user as a marihuana-, psychedelic-, or opiate-using subject. Obviously, it would have been possible to put those who had used all three types of drugs into all three categories. But we decided instead to assign each subject to only one category according to whether marihuana, a psychedelic, or an opiate was his or her drug of choice. This decision represented a departure from those studies-and there have been many of them-that have considered the subject's drug of choice to be irrelevant. In my view, to have studied how well someone controlled a particular drug that he did not like very much would have been very much like studying moderate ice cream users while including some subjects who did not care for ice cream but did have a taste for candy.

In constructing the precise conditions for selecting and assigning subjects to the controlled, marginal, or compulsive categories, five issues were given special consideration.

First, pattern of use over time was weighted more heavily than the total number of days of use. For example, in the two years preceding their initial interview, controlled users might have used opiates on as few as Zo occasions or on as many as 365 occasions, but they were not permitted to have had more than three instances of from four to fifteen consecutive days of opiate use. (In fact, as will be discussed later, no controlled users approached the upper limit of 365 days of use.) By contrast, compulsive subjects were required to have had a number of long periods of consecutive daily use. Marginal subjects fell between these extremes, oscillating between periods of frequent use, infrequent use, and abstinence.

Second, in assigning opiate users to one of the three categories, we regarded the likelihood of physiological addiction, which was correlated with consecutive daily usage, as more important than the total number of using days. The research team wanted to ensure that those designated as controlled users had not been physiologically dependent on opiates for at least two years. Since the development of clear physiological dependence requires about two weeks of consecutive daily use (Jaffe 1975), the sample of controlled users was limited to those whose daily using sprees were of no more than fifteen days' duration. At the same time, the criteria allowed for some restricted spree use because we had found that the pilot project subjects who had managed their use of opiates quite well and had avoided adverse consequences had been able to indulge in a few short periods of consecutive daily use. For example, several subjects who ordinarily used once a week or less had increased use to every day or almost every day during a vacation or under some other special set of circumstances and had then returned to their usual pattern of less frequent use. As it turned out, our controlled subjects' sprees tended to be much shorter (four to five days) than the allowed maximum of fifteen days. The research team's leniency in ': regard to length of sprees and total number of days of use permitted in a two year period reflected my own sense that we would probably have difficulty in locating very many carefully controlled opiate users.

Third, all controlled and marginal subjects were required to have used their drug at least ten times in each of the two years preceding the initial interview (with some modifications if the subject met the other relevant conditions for at least the four preceding years). One purpose of this rule was to ensure that use had been regular enough to test the subjects' ability to maintain some level of control. In effect, it eliminated the major group of experimental or minimal users that has often been included in studies of occasional use and that probably accounted for the large numbers of users treated in the surveys discussed in appendix C. The other purpose of the rule was to ensure that subjects were recent or active users.

The fourth issue relating to subject selection-a much more complicated matter-was the level of other drug use. Those assigned to the category of controlled subjects were required to have been in control of all the drugs they used (except tobacco) for at least two years preceding the initial interview. Because my study probed the general issue of control over intoxicant use, it was important, for example, to avoid counting as controlled opiate users those who were able to keep their opiate use within prescribed bounds but who were coincidentally abusing barbiturates or alcohol or some other drug. Therefore, daily but moderate consumption of alcohol was deemed acceptable, but daily use of any other licit drug (except tobacco) or of any illicit drug disqualified a candidate from assignment to a controlled category. Although I believe that' daily tobacco use is risk-laden and abusive, to have required controlled users to be less than daily users of tobacco would have eliminated many otherwise suitable candidates. As it turned out, 83% of controlled opiate users, 59% of controlled marihuana users, and 53% of controlled psychedelic users in the combined sample were daily tobacco users.

The question remained, however, whether less than daily use of a large number of drugs might not still constitute overall abuse. What about including as a controlled subject a once-a-week heroin user who made use of marihuana once every other day and of barbiturates every third day, and who always had a drink before dinner? The possible permutations of different drugs and schedules of use made this problem especially difficult. Since, in any case, we could not gather data about all drug use in sufficient detail to make these distinctions, we opted to add the following requirement concerning use of other drugs: if either the candidate or the interviewer felt that total or overall drug use (including even less than daily use) interfered with the candidate's ability to meet ordinary social obligations, he or she was rejected as a controlled subject. This refinement had the disadvantage of being more subjective than our other criteria, but in practice it enabled a rough judgment to be made relatively easily. When in doubt, we elected to err on the conservative side and not to assign a questionable subject to the controlled category. In fact, most controlled subjects did not use a great many other drugs very often, and as will be indicated in discussing the validity of the data, there was good reason to expect that the subjects' own estimation of the effects of drug use on their ability to function would be accurate. In the end, only seven candidates whose opiate use was controlled were rejected for the combined DAC-NIDA sample because their use of other drugs interfered with their functioning, although each of the other drugs in question was used on a less than daily basis.

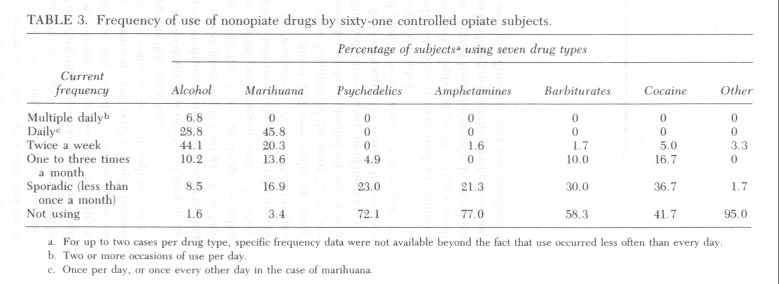

The average frequency of use, by the controlled opiate subjects in the combined sample, of seven types of other drugs during the year preceding initial interview is shown in table 3 . It is striking that at least 41.7% of these subjects completely refrained from using five types of drugs (including "other"): psychedelics, amphetamines, barbiturates, cocaine, and such "other" drugs as inhalants and PCP. Moreover, when such subjects did take nonopiates, their consumption was generally quite moderate. About 36% of the sample used alcohol on at least a daily basis. About 46% were coded as "daily" marihuana users, but in this one case the definition of the word "daily" was limited to use once every other day because all the controlled subjects used at that lower frequency. None of the controlled subjects used any of the other five drug types more often than once a week. In summary, the average frequency of nonopiate drug use among controlled subjects was low enough to support the statement that their use of all drugs was controlled.

The fifth issue relating to selection of subjects concerned an additional category designated as "other." If a subject simply did not fit the basic conditions required of all subjects, he was omitted from the sample, but a subject who did meet these general conditions but failed to meet the specific conditions for either the controlled, marginal, or compulsive category was classified as "other" (see table 1). Most "other" subjects fell into two major subgroups: (1) those who would have been classified as controlled except for the compulsive use of one other drug, almost always marihuana; and (2) those whose pattern of use was not accommodated by the criteria. For example, one subject had used opiates for some eight years and had used them fourteen times during the year preceding the initial interview, but he had abstained for four years before that. Although he was clearly a moderate user, his current pattern had not been continued for the two years preceding the interview that we required as evidence of stability of use. Data on "others" provided us with valuable qualitative information about the range in patterns of drug use that fell outside the criteria we had selected to define controlled, marginal, and compulsive users.

The following six cases illustrate the types of using patterns we assigned to the three major subject categories.

1. Arthur, a "controlled user," was a forty-year-old white male who had been married for sixteen years and was the father of three children. He had lived in his own home in a middle-class suburb for twelve years. He had been steadily employed as a union carpenter and had been with the same construction firm for five years. During the ten years prior to the first interview, Arthur had used heroin on weekends. For the first five years of use he occasionally injected during the week but midweek use had not occurred during the previous five years.

2. Greg, a "controlled user," was a twenty-seven-year-old white male, a full-time undergraduate student in special education, participating in a work-study program. He came from a middle-class Irish background and lived at the time of the interview with a woman student. He had used heroin two or three times per month for three years before the interview but had shifted his pattern a year before the interview to four times a month, with occasional three-day periods of use. He also had had two four-day using sprees within the previous year.

3. Max, a "marginal user, "was a twenty-seven-year-old white male from a lower-middle-class background who had completed high school only. He lived with three roommates in an apartment building he owned. He had been a trucker but was training on the job as a luncheon chef. For two years prior to interview he had used heroin about four tunes a month, either once or twice a week. During the year prior to interview he had used heroin daily (while dealing) for one month.

4. Bert, a "marginal user," was a twenty-nine-year-old white male from a lower-class background, unemployed at time of interview. During a year-long period of prescribed opiate use, which had ended a year and a half before he was interviewed, he had exaggerated his complaints of pain from an eye problem in order to obtain Dilaudid, which he had used nonmedically on an average of three times per week. In a few instances he had used for three or four days in a row, and once or twice he had used for more than half the days in a month. Following that period of use, he had "cut back" to the pattern of nonmedical use he described on interview: three times a week on a strict schedule ("just weekends and in the middle of the week; you can't get addicted that way"). If this pattern of use had continued for six additional months, he could have been reclassified as a "controlled user."

5. Phil, a "compulsive user," was a twenty-two-year-old white male from a lower-class background who lived with his divorced mother and two siblings. He had left school after the ninth grade but had later obtained a general equivalency certificate. At the time of interview he was unemployed but had held a series of short-term jobs, mainly as a factory worker, since his return from military service. Two years before his first interview he had been using Dilaudid and about twenty Percodan daily, which he had got by breaking into drugstores. His periods of daily use were frequent and usually lasted for about three weeks ("until the supply ran out"). Following some months in jail, he had used heroin and Dilaudid approximately twice a week during the year before his interview.

6. Bob, a "compulsive user," was a twenty-six-year-old white male who lived alone, a college graduate with a degree in psychology. Following separation from his wife and child three years before interview, he had worked sporadically at part-time jobs. Dealing drugs had become his major source of income. He had used heroin at least three or four times per week since beginning use thirty months before interview and had had many periods of daily use lasting as long as two weeks.

LOCATING SUBJECTS. With limited funding and without the benefit of hard data from previous research regarding the number and characteristics of controlled or even occasional illicit drug-takers, it was not possible to draw a random, or representative, sample for study. The only possibility was for sub jects to self-select into the study, and this method resulted in uncertainty about the degree to which they were representative of all controlled, compulsive, or marginal users. Priority was placed on the recruitment of controlled users. I expected that some compulsive and marginal subjects would be recruited in the process of seeking controlled subjects, and that if more subjects were needed and time permitted, at least the compulsives would be relatively easy to locate.

Five recruitment techniques were used in both the DAC and NIDA studies.

1. The researchers described the project to friends and colleagues who had some professional or personal contact with drug users, asking them to spread the word about the research and to refer to us anyone who might possibly be considered a moderate marihuana, psychedelic, or heroin user.

2. Brief descriptions of the research, including notices to be posted soliciting subjects, were sent at several times to more than eighty high schools, universities, drug-treatment programs, and counseling and other social service agencies in the Boston area. Follow-up telephone conversations took place with representatives of many agencies, either in response to their questions about the project or in order to encourage their cooperation. Some agencies expressed concern about confidentiality, about the possibility that the research would interfere with a therapeutic relationship, or about whether the research should be done at all, but almost all of them were willing to help by posting a "wanted" notice.

3. Following Powell's example ( 1973), advertisements soliciting subjects were placed periodically in area newspapers. The ads took several forms. For example:

Drug Research Subjects Wanted for a study of nonaddicted, non medical occasional opiate use. Subjects with controlled semi-regular use of heroin, morphine, Demerol, Dilaudid, codeine, Percodan, etc. needed for paid, fully confidential interview. Call Mon.-Fri., 10-4, (phone number).

4. Subjects who went through the interview process were asked to refer other drug users who might be interested in participating. Very occa sionally, subjects who claimed to know a lot of other users (particularly opiate users) were offered a bounty of $5 for everyone they referred who proved to be suitable for interview. Most interviewees, however, seemed willing to refer friends without financial incentives simply be cause they had enjoyed the interview and had decided the research did not pose a threat to confidentiality. This snowball technique was a particularly fruitful source of subjects.

5. Early in the DAC study some interviewees told us about fellow drug users who would have. been likely candidates but were not willing to talk to the researchers. In order to reach this more reticent group, we decided after several months to train some of our own subjects for recruiting and interviewing. Eventually eight of these indigenous data gatherers were employed for varying lengths of time and were paid $15 or $2o for each interview they conducted.

We learned a good deal about tracking down suitable candidates from our experience in recruiting subjects.

First, as was expected in view of the more deviant status of opiate users, it was more difficult to contact and arrange interviews for controlled users of opiates than for compulsive opiate users or for any type of marihuana or psychedelic users. Without exception, controlled opiate users expressed much more concern about confidentiality than did any of the others. All of the controlled subjects were well aware of the illegality of what they were doing, but the controlled users of opiates were also aware of the extreme sense of deviance associated with their use; yet they lacked both the indifference regarding social acceptance shown by the marihuana and psychedelic users and the sullen disregard for consequences shown by the compulsive opiate users.

Second, again as expected, most of the people who contacted the research staff or whom indigenous data gatherers asked for approval to interview were not suitable candidates. Figures for a two-year period indicated that 70% had been rejected during screening discussions.

Third, with opiate users in particular, much time was required to secure a single viable interview, not counting the time spent on the interview itself. Researchers and indigenous data gathers spent an estimated ten hours on recruitment for each viable interview with an opiate user. Dealing with ineligible candidates and broken appointments accounted for most of this extra time. Fourth, the most fruitful means of securing interviews involved personal contact between a candidate and someone who could provide reassurance about the nature of the study. Seventy-seven percent of marihuana subjects, 67% of psychedelic subjects, and 42% of opiate subjects were recruited through referral by another subject, through a friend of the research team, or by an indigenous data gatherer.

Fifth, the use of indigenous data gatherers to recruit subjects was generally successful. Although considerable time was invested by the research team in training and supervising these special interviewers, they in turn were able to recruit many subjects who would not have been willing to be interviewed by the research staff, and the quality of their interviews was quite good. Four indigenous data gatherers proved so capable and successful that their participation was extended to other areas of the project, such as interpretation of case material and selection of excerpts. The primary drawback to using indigenous data gatherers was the loss of follow-up data, to be discussed in a later section.

MEANS OF GATHERING DATA. At first contact with a potential subject (usually by telephone) my staff or indigenous data gatherers described the purposes of the research, the procedures for safeguarding confidentiality, the content of the interview, and the payment. Before making arrangements for an interview they also administered a brief series of screening questions, covering age, sex, current major activities, all drugs currently used, drug treatment history, frequency of use for selected drugs, any past or present problems associated with drug use, and the candidate's future availability. Because candidates did not know the details of the selection criteria, it was very difficult for them to deceive the research staff deliberately about their eligibility, and consequently our rejection rate was high.

Although interviews could be arranged for any time of the day or week and could be conducted either at the research offices at The Cambridge Hospital or at some other location such as the subject's home, most took place during normal business hours, and virtually all were held at the hospital. The screening procedure was repeated before beginning the interview.

The extent to which we were able to reassure candidates about confidentiality obviously had a critical effect on recruitment and on the quality of the interview itself. Nine procedures were used to safeguard the interviewees' identity.

1. No subject's name or any other identifying information was available to anyone outside the research proejct.

2. Interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed, and these records were assigned code numbers. A list of matching code numbers with identifying information for follow-up purposes was held by a party living outside the United States who was in no way formally connected with the proejct, making it virtually impossible for this information to be subpoenaed. (Later, after receiving assurances from law-enforcement personnel that they would not subpoena records, we transferred identifying information into a local safe-deposit vault.)

3. Identifying information on subjects interviewed by indigenous data gatherers was known only to those data gatherers.

4. Subjects were told that they could decline to answer any question without explaining why.

5. They were shown how to operate the tape-recorder and invited to shut it off at any time if they wished to discuss something "off the record" or if they wanted a moment to decide whether to reveal certain information.

6. Subjects were instructed to alter the names and other identifying information concerning other people whom they might discuss.

7. At the close of the interview, subjects were given the opportunity to review and erase any part of the tape.

8. In writing up cases, care was taken to alter certain information so that a reader who knew the subject could not identify him. (Several subjects were asked to read their case histories, and all were satisfied that they could not be identified even though a fair sense of the events and characteristics of their lives had been retained.)

9. No information provided by one subject was told to another subject, even when the two were closely related and knew that both interviews had been conducted.

Procedures for protecting confidentiality were explained to each participant at the beginning and close of the interview, and each received a written statement of these safeguards signed by the interviewer. Having subjects sign a written statement of informed consent for participation in the research would simply have increased their risks; therefore, consent was given orally, and a statement noting this was signed by the interviewer and placed on file.

Because so little was known about controlled users, it seemed likely that a lengthy, semi-structured interview would be the most appropriate instrument for collecting data. In the interest of economy, however, some experimental interviews based on a shorter, structured questionnaire were conducted early in the pilot study with various drug-takers. These experimental interviews proved to be inadequate. Responses were minimal; the reasons for choosing between alternatives remained unexplained; sufficient information for assessment of personality was not obtained; and later the subjects described the experience as an unpleasant chore. Soon a semi-structured interview was developed that elicited certain fixed information from all subjects but allowed them to respond on their own terms rather than requiring them to choose between fixed alternatives, and that also permitted them to tell stories and shift topics as they wished. This approach demanded skillful interviewers and complicated the reduction of the data for statistical analysis. But this type of interview, which included questions designed to elicit information that would help us decide on the personality structure of the applicant, the degree of emotional difficulty, and the degree of coherent, stable emotional functioning, allowed us to pursue important psychological and social issues as they arose. In addition, it proved tolerable for the subjects.

The initial semi-structured interview covered seven major areas:

1. Basic demographic information (age, sex, race, social class, education, employment)

2. Family history

3. History of licit and illicit drug use

4 . Current social circumstances, including relationship to work, school, family, mate or spouse, and friends

5. Details of drug-using situations and attitudes toward use 6. Interviewer's assessment of general psychological state

7. Opinions regarding drug laws and regulations, drug education, drug culture, and related issues. (The interview schedule appears in appendix A.)

The content of the interview was altered at several points during the study as our contact with subjects suggested new areas that deserved attention and as criticism and recommendations were received from indigenous data gatherers. Making these changes did not necessarily mean that questions asked of one subject were not asked of another, because additions could be incorporated into a follow-up interview as needed. (The basic follow-up or reinterview schedule appears in appendix B.) Individualized questions were added for subjects whenever topics raised in the initial interview required further clarification. Usually these questions were devised during our biweekly research conferences when subjects were discussed and personality assessments made.

Initial interviews generally lasted for two hours, although some were much longer. Follow-up interviews were somewhat shorter. Subjects were paid at least $10 for each interview; they might be paid up to $20 if the interviewer felt that the larger amount would help secure an interview (usually a reinterview) or, more rarely, as reimbursement for travel expenses. FOLLOW-UP. At the initial screening and at the beginning of the interview, subjects were made aware of our interest in follow-up, but recontact information was not solicited until the close of the interview. This practice developed because some qualified candidates had refused to come in for an interview when full identification for the purpose of follow-up was made a precondition. But after discussing confidentiality face-to-face with the research staff and after having experienced the interview, 97% of all subject were willing to provide us with some means of contacting them. Recontact information might consist of a phone number or address or of similar information for another person, sometimes a parent, who would know where the subject could be reached even if he or she had moved to a new location. Subjects were advised (1) that if the interviewer reached someone else when trying to contact them by phone, the research would be described as an opinion survey and no reference to drug use would be made; and (2) that recontact letters would omit any reference to drug use. To assist the follow-up process each subject was given a business card with the name, telephone number, and address of the interviewer and was encouraged to call if he or she changed locations or wanted to schedule a reinterview or to ask further questions about the research.

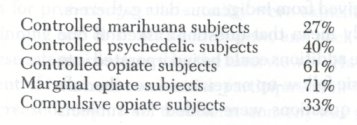

In addition to letters and phone calls to subjects or second parties, followup efforts included advertisements in area newspapers soliciting reinterviews with subjects who could not be contacted. On average, three attempts were made to arrange a follow-up interview for each subject, excluding those for whom no recontact information was available and those who initiated their own follow-up; but as many as eleven attempts were made in some cases. Follow-ups occurred approximately twelve to twenty-four months after the initial interview. The follow-up rate for all subjects was 47%; the breakdown by categories was as follows:

No subject who was recontacted refused a follow-up interview. Failure to follow up was largely due to subjects' relocation (72% of the opiate users) and the lack of recontact information (28% of the opiate users). Some subjects refused to provide recontact information to the research staff, although most of them initiated follow-up themselves. The major responsibility for lack of recontact information rested with the indigenous data gatherers, whose follow-up rate in relation to all subjects was only 31%, which sharply reduced the percentage of follow-up for the entire study. The failure of a few of them to follow subjects had to do with changes in their own life situations, such as separation or divorce and relocation.

The Data

VALIDITY. In some public discussions of this research, questions about the validity of the data (especially those on controlled opiate users) have been raised. These questions have been put in such a way as to suggest that no such users existed or could exist and that these subjects must have deceived the research team about the level of their drug use and other critical issues. One commentator even criticized the project staff for not performing urinanalyses on controlled users to verify that they were not addicted, adding that if such subjects had had nothing to hide they would have been willing to cooperate in that manner. While questions about the validity of any research data are always appropriate, the presumption that many drug users distort the accounts of their use is not entirely reasonable.

A number of validity studies that have been conducted with drug- or alcohol-using respondents who appear to have had good cause for concealing sensitive information have shown that data from such individuals tend to be both reliable and valid. Studies of alcohol users, for example, have supported the validity of adolescent surveys (Single, Kandel & Johnson 1975), of selfreports of life-history data from alcoholics in voluntary treatment (Sobell & Sobell 1975), and even of self-reports of alcohol-related arrests (Sobell, Sobell & Samuels 1 974) . Validity studies concerned primarily with drug use have produced similar results. This is true of house-to-house surveys of psychotropic prescription-drug use (Parry, Batter & Cisin 1971), studies of a range of illicit drug use (Whitehead & Smart 1972; Amsel et al. 1976), and more particularly, studies involving illicit narcotics use (Ball 1967; Maddux, Williams & Lehman 1969; Stephens 1972; Maddux & Desmond 1975; Bonito, Nurco & Shaffer 1976; Robins 1979).

There are, it seems, few exceptions to these findings of high reliability and validity. When Newman et al. (1976) found discrepancies among multiple selfreports of age of first use of narcotics, they were able to give two plausible explanations for the discrepancies: first, subjects may have been motivated to oyerstate the length of their drug use in order to enhance their chances of admittance to a drug-treatment program; and second, both the subjects and the staff who did the interviewing seemed to attach little importance to the age of first use. Another apparent exception to findings of high reliability is a study by Chambers and Taylor (1973), who found that only one-third of methadone patients accurately reported their ongoing illicit drug use. But as Maddux and Desmond (1975) have pointed out, "Some patients probably denied their drug use because they feared disapproval or adverse action from the program staff."

In my project, rapport with subjects was excellent. Most subjects felt free to discuss even the most intimate aspects of their lives, and the interviewers were generally satisfied that subjects were truthful. Several factors accounted for this rapport. (1) Staff were not related to a treatment program. (2) Staff approximated the age range of subjects and therefore were probably perceived as trustworthy or sympathetic. In fact, many subjects supposed that the staff members themselves used illicit drugs. (3) The atmosphere of the interview was casual and the time allotted was sufficient to allow for "off the record" conversations before, during, and after the interview. (4) The various steps taken to assure confidentiality helped place the subjects at ease. (5) All the interviewers were trained to ask for the same information about important aspects of attitudes and actions concerning drug use and to pursue contradictions when found. (6) Interviewers were also trained to ask about and pick up nuances of psychological functioning,

Even though the staff and I had good reason to believe that the information we collected would be valid, we employed several techniques to test the veracity of subjects' statements.

First, the interviews were structured so that selected topics were raised more than once in slightly different ways at widely spaced intervals. Inconsistent responses could thus be detected at the time of the interviews and attempts made to resolve any discrepancies.

Second, follow-ups provided another opportunity to identify inconsistencies. A set of core questions, most of which concerned drug use, was repeated at follow-up. Therefore, if a subject initially distorted his report of his relationship with his wife or the manner in which he used barbiturates, the same distortions would have had to occur during a follow-up interview held twelve to twentyfour months later in order to escape detection by the researchers. Follow-up interviews also provided an opportunity to enhance personality assessment, to learn more about the nicities of drug use, and to pursue other specific issues raised in the initial interview that the research team felt needed clarification or verification.

Third, the subjects who were recruited by other subjects provided opportunities to cross-check data. Thirty-four percent of all subjects in the combined sample were socially connected in some way to at least one other subject from the three samples. Among controlled opiate users, about whom the greatest skepticism exists, the percentage of subjects related to another interviewee was 43%. The rule on confidentiality, stating that no subject would be told what another had said, proved important with respect to this validity check.

For example, one controlled opiate subject, Mary, reported that she was concerned about her mate's somewhat increased level of opiate use and strongly suspected he was not being honest about using the drug with other people. When her mate, Sam, was interviewed, he discussed using with other people and his attempts to keep this a secret from Mary. Both subjects were followed up approximately one year later. A detailed analysis of initial and follow-up data revealed that fifty-eight topics had been discussed by both subjects or reviewed at follow-up. Corroboration occurred on fifty-five of these items. Areas of agreement included demographic information, current activities, drug-using history, current drug use, drug-using practices, and criminal activities. In addition to Sam's hidden opiate use, agreement occurred in many other areas where the reported behavior might have been regarded negatively (for example, dealing, fleeing a warrant for arrest, receiving welfare payments while working, contracting hepatitis). The three areas of disagreement were comparatively minor and centered around the circumstances of Sam and Mary's first use of heroin together. Mary reported that she had first used heroin with her sister and brother-in-law and that Sam had not participated because he feared the drug. At her next try, she said, Sam had joined the group and had fainted immediately after injection because of his fear of needles. Sam did not report that Mary had first used without him or that he had fainted (although he did note that he had become nauseous). The disparity in their reports was not only minor but came about through Sam's omitting material rather than by direct contradiction.

Because indigenous data gatherers had continuing personal contacts with the subjects they had interviewed, they had many informal opportunities to check the validity of the data they collected. Our own continuing relationships with these data gatherers also provided us with a host of opportunities to test data about them. Indigenous data gatherers served in effect as intensive case studies.

During the NIDA study, testing the validity of data was further formalized by actively recruiting a "friend" or collateral for each subject interviewer. Subjects were asked to send in close friends who had known about their drug use for at least two years. (No restrictions were placed on the friends' drug use.) This request was explained by telling subjects that we wished to learn more about how the attitude of people they knew might have been affected by the subjects' drug use.

One or more friends were recruited for each of seventeen NIDA opiate users. Interviews with friends were shorter than those with the subjects themselves, concentrating on the friends' perceptions of the subjects' drug use and other behavior. Comparison of a friend and a subject could be made across a large and variable number of topics. (One analysis involving a controlled opiate user yielded twenty-six topics on which information was available concerning both parties.) Although data from friends sometimes slightly altered our understanding and interpretation of a subject's statements, instances of contradiction that would have necessitated a change in coding of the data were so rare and minor that after twenty-two interviews the procedure of recruiting friends was abandoned. For example, in the analysis of the controlled opiate user just mentioned, disagreement between the user and the friend occurred on only one of the twenty-six topics. This disagreement concerned whether the subject and friend had been using opiates together once every three or four months, as the subject reported, or once every two or three months, as the friend reported.

Overall, the application of these procedures confirmed our sense that subjects were truthful. When we acted upon our original plan to discard interviews whose validity had been brought into question, only three interviews for the DAC and NIDA studies together had to be rejected. In each instance the interviewer had expressed concern about validity before the problem was officially confirmed by examining friends' interviews or by identifying inconsistencies between the subject's initial and follow-up interviews.

Perhaps the most striking feature of the interviews was the subjects' willingness and at times eagerness to discuss their personal relationships, drug use, criminality, sexual behavior, and other matters that might have caused them embarrassment in another context. Subjects apparently felt well protected and rarely exercised their option to reject a question or turn off the tape recorder. In fact, deleting from tapes any identifying information that might have incriminated a host of people became something of a chore for the research staff. The team and I speculated that many subjects had used the interviews to relieve themselves of much information that they could not readily share with others. The chief problem was not to "get at the truth" but to place reasonable limits on this type of confessional behavior so that the interview did not evolve into a therapeutic encounter. ,

DATA REDUCTION. Most of the time spent on this project was devoted to reducing the vast amounts of information-literally thousands of pages of tran script-into manageable form for analysis and then carrying out that analysis. Data reduction took three forms: case-history analysis, excerpting, and coding. To begin with, case notes were prepared from the transcripts and tapes for presentation to other staff. Attendance at case presentations varied, but it often included an indigenous data gatherer who contributed direct experience with the drug, and with drug users, to the discussions. Periodically, an interested outsider was invited to participate in order to help identify biases among the staff. Notes on the sometimes heated discussions of cases were made a part of the subject file, and from these notes and the transcripts, case histories (like those appearing in chapters 1 and 2) were drafted and revised by other staff. Next, after the transcripts had been carefully reviewed, material was ex cerpted that seemed to represent the point of view of a number of subjects, suggested some new perspective, or encapsulated the subject's overall current and past personality functioning. Excerpts such as those appearing in chapters 4 and 5 were circulated among staff and indigenous data gatherers for comment. In this way the richness of the original material was preserved, and both the variety and the commonalities among subjects, including their attitudes, were identified.

Finally, working from transcripts and tapes (as needed), the staff coded each subject's initial and follow-up interviews separately for computer analysis. Since coding required translating the subject's language into a set of exclusive, fixed categories, it was inevitably subjective. (The cases and excerpts presented in this book are intended in part to provide access to untransformed material.) At least the coders, who included both indigenous data gatherers and staff, proved consistent in their judgments. The first few attempts by a new coder were checked for agreement and accuracy by more experienced staff members. In addition, during the project, twenty cases that had been coded were selected at random and assigned to another staff member or indigenous data gatherer for coding. The second coder did not know that someone else had already coded the cases and thus had no motive for taking special care in preparing them. With more than zoo items to be coded per interview, there was disagreement on fewer than 2% of the items.

The style of analysis employed on the project was mixed, incorporating both an individual, case-history, qualitative approach and a more selective, quantitative, statistical approach. Each method included a subjective element and provided a different, though not necessarily contradictory, picture of control over drug use. The statistical overview presented later in this chapter is intended to restore in some degree the general trends and distribution of differences that are obscured by the case-history approach.

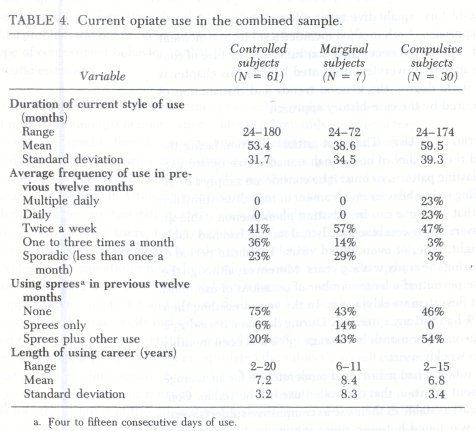

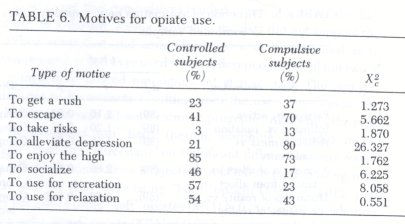

STABILITY OF CONTROLLED USE. The most critical question facing the research staff concerned the stability of occasional, nonaddictive opiate use. Can controlled use be a lasting pattern, or must it be considered simply a brief, transitional stage preceding either heavier involvement or total discontinuance of use? We discovered that such use can be a lasting phenomenon (table 4). Some of the controlled users in our combined analytical sample had had stable patterns for as long as eight, nine, or even fifteen years. The mean period of current controlled use during the study was 4.5 years. Moreover, although the criteria for controlled use permitted a large number of occasions of use, most subjects were infrequent (less than weekly) users. In the year preceding their initial interview, only 26% had had any spree use. During the same period 23% had used opiates less than once per month on average, 36% had been monthly users, and 41% had been weekly users.

That our controlled subjects had maintained moderate use for an average of 4.5 years showed without question that controlled use can be stable. Controlled subjects were at least as stable in their use as compulsive subjects were; no significant difference was found between these groups in the duration of their current using styles as displayed in table 4: t(89) = -0.85, p = 0.40. Unfortunately, data on marginal subjects were not amenable to statistical analysis because only seven of the users in our sample fell into that category. But data on their frequency of opiate use and using sprees in the twelve-month period preceding the initial interview show that while this group was by no means so intensive in the use of opiates as were compulsive subjects, its members did not demonstrate the consistent restraint and careful manner of use that characterized controlled users. The very existence of marginal users, however, makes a strong case for a continuum of opiate-using styles; as the detailed case histories indicate, assessing the level of abuse for this intermediate group was difficult (Zinberg et al. 1978).

Nevertheless, one who accepts the traditional view that opiate users must progress from experimental to moderate use and then on to increasing involvement with opiates and finally to addiction might still argue that our subjects simply had not reached the point in an opiate-using career where compulsive use develops (Robins 1979). But our findings do not support this view. Since there was no significant difference (t[89] = 0.51, p = 0.62) between the lengths of the total using careers of the controlled subjects and the compulsive subjects, it can be concluded that the two groups had had equal opportunity to become compulsive. Moreover, the length of the total using careers of the controlled subjects-a mean of 7.2 years-suggests that they had already had ample opportunity to progress to compulsive use.

The notion that opiate users always advance through stages of increasing drug use is also contradicted by the following facts about the careers of our compulsive subjects. About half (47%) of them had never had a substantial period of infrequent use; they had been compulsive users every year of their using careers. Only 23% of them had had any years of controlled use. Further, the average duration of that small percentage's longest period of controlled use (1.3 years) was significantly less than the current period of control in the sample of controlled users (4.1 years), measured in years of using career: t(55.3) = -7.07, p < 0.001. Thus, it appears that only a few long-term compulsive users passed through an early stage of controlled use, and those who did so tended not to remain in that stage for long.

Another question-whether any of our controlled users had a past history of compulsive use-is relevant to the issue of the stability of controlled use. Twenty-nine (48%) of the controlled subjects had had one or more such periods during their using careers. It might be argued, therefore, that their current period of controlled use represented only a temporary remission from compulsive use or a tapering off along the way to becoming abstinent. Again, however, the data strongly suggest that these subjects' current controlled using style was a highly significant segment of their using career. For example, their current period of controlled use (mean = 9.5 years) was significantly longer than the average duration of their longest periods of compulsive opiate use (mean = 1.6 years): t(28) = 4.62, p < 0.001. And their current period of controlled use also represented 45% of their total using careers, which included periods not only of compulsive use but of other opiate-using styles as well.

Although there was no way to foretell whether all our controlled subjects would eventually progress to more intensive use (Robins 1979), this seemed unlikely. Follow-up data available for 6o% of the controlled subjects show that 49% had maintained their using pattern and 27% had reduced use to levels below those required for them to be considered controlled users. (Of these, 24% had become abstinent.) Another 11% had maintained their controlled pattern of opiate use but had begun using other drugs too heavily for us to consider them controlled subjects. Only 13% (5 subjects) had increased their opiate use sufficiently to enter either the marginal (8%) or the compulsive (5%) category. Of the two subjects who became compulsive users, one had had a significant period of dependency on heroin and the other a period of dependency on barbiturates before becoming controlled; and one of these had returned to controlled use at the time of reinterview. Even if all these subjects should eventually become addicts, their period of controlled use would form a long and distinctive segment of their using careers. At the time of initial interview, their current period-of controlled use represented 6o% of their opiate-using careers.

CRITICAL DIFFERENCES BETWEEN CONTROLLED AND COMPULSIVE OPIATE USERS. Although the criteria for admission to this study resulted in the creation of subject groups with quite different patterns of use, I wondered initially whether these groupings would prove to be significant and distinct in terms of both the quality and the consequences of their drug use. As it turned out, comparisons made between the controlled and the compulsive opiate subjects did reveal several differences that were closely related to the com monplace distinctions made between drug users and drug abusers.

A highly significant difference was found between controlled and compulsive subjects in the ability to keep opiates on hand without using them. 59% of controlled subjects as against only 17% of compulsive users were able to deter use when opiates were immediately available: ![]() (1)= 11.798, p = 0.001. (Here and elsewhere, subscript c in

(1)= 11.798, p = 0.001. (Here and elsewhere, subscript c in![]() indicates use of Yates Corrected Chi Square.) Controlled users also had significantly lower peak frequencies of opiate consumption during their using careers than compulsive users: X²(4) = 33.678, p < 0.001. Only 23% of controlled subjects, compared with 87% of compulsives, had ever used opiates more than once per day. This difference was not simply an artifact of the criteria used to define the subject groups, for these criteria placed no restrictions on frequency of use prior to the two-year period preceding subjects' initial interviews, and within this two-year period controlled users were permitted to have had brief periods of spree use. In addition, a notable difference, which was partially an artifact of the subject criteria, existed between the two groups in terms of whether they had ever used a nonopiate drug compulsively:

indicates use of Yates Corrected Chi Square.) Controlled users also had significantly lower peak frequencies of opiate consumption during their using careers than compulsive users: X²(4) = 33.678, p < 0.001. Only 23% of controlled subjects, compared with 87% of compulsives, had ever used opiates more than once per day. This difference was not simply an artifact of the criteria used to define the subject groups, for these criteria placed no restrictions on frequency of use prior to the two-year period preceding subjects' initial interviews, and within this two-year period controlled users were permitted to have had brief periods of spree use. In addition, a notable difference, which was partially an artifact of the subject criteria, existed between the two groups in terms of whether they had ever used a nonopiate drug compulsively: ![]() (1) = 4.337, p < 0.04. As expected, far fewer controlled subjects (59%) than compulsive subjects (83%) had such a history.

(1) = 4.337, p < 0.04. As expected, far fewer controlled subjects (59%) than compulsive subjects (83%) had such a history.

These examples indicate that controlled users were more moderate about drug use than compulsives and, as might be expected, that they also suffered fewer negative consequences. Fewer, although not significantly fewer, controlled subjects than compulsive subjects-36% as against 45%-had had any adverse reactions from opiates, and when they had had such reactions they had responded differently. After a negative experience controlled subjects were likely to take new precautions or to suspend use, while compulsives were more likely to maintain their old pattern: X²(1) = 3.970, p < 0.05. Controlled subjects were significantly less likely to have been treated for drug use (41% as opposed to 77% of compulsive users: ![]() [1] -8.892, p = 0.003). In addition, the controlled subjects were treated less often; only 36% had been treated more than once, compared with 61% of the compulsives: t(28.7) = -2.86, p = 0.008.

[1] -8.892, p = 0.003). In addition, the controlled subjects were treated less often; only 36% had been treated more than once, compared with 61% of the compulsives: t(28.7) = -2.86, p = 0.008.

Another relevant finding related to current functioning and especially to employment. A significantly greater number of controlled users (37%) than compulsives (10%)-![]() (1) = 6.267, p = 0.01-worked full-time. And a similar though not significant trend existed in relation to part-time employment, with 44% of controlled opiate users employed part-time versus 27% of compulsives. Self-related performance at work showed the same expected difference between the two groups, with 71% of the controlled subjects "doing well" as compared with 62% of the compulsives. Finally, more controlled subjects (55%) than compulsives (39%) reported that they liked their work.

(1) = 6.267, p = 0.01-worked full-time. And a similar though not significant trend existed in relation to part-time employment, with 44% of controlled opiate users employed part-time versus 27% of compulsives. Self-related performance at work showed the same expected difference between the two groups, with 71% of the controlled subjects "doing well" as compared with 62% of the compulsives. Finally, more controlled subjects (55%) than compulsives (39%) reported that they liked their work.

No definite causal relationship between drug use and the ability to work is implied by these findings; differences in work performance between the two groups may have been due to a variety of factors. At the same time, there does not seem to have been a relationship between compulsives' relatively poorer performance and a lack of social opportunity, as indicated by variables relating to social background. There was no difference between controlled and compulsive users in terms of the reported socioeconomic status of their family while they were growing up (X²[3] = 1.361, p = 0.71). There was no difference in the total number of school years they completed (t[44.1] = 1.29, p = 0.21). Insofar as these factors affected future employment, controlled and compulsive subjects might have been expected to do equally well in their work life.

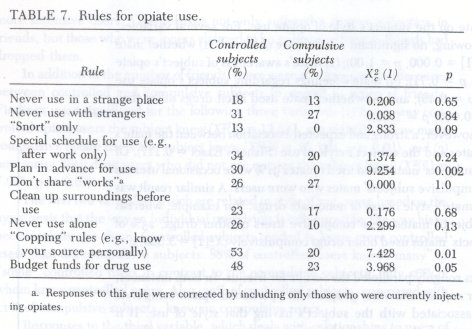

Besides the variables already discussed, many other variables-some associated with availability of and experience with opiates, some with set (personality), and some with setting-were examined in an effort to pinpoint other critical differences between controlled and compulsive opiate users.

DRUG VARIABLES. Since the availability-or, rather, nonavailability-of drugs is viewed by many policymakers as the most crucial factor in reducing use, the apparent moderation of our controlled users would be less striking if it could be shown to have resulted from a lack of opportunity to use opiates rather than from individual restraint. Yet our analysis of variables relevant to the question of opportunity to obtain drugs showed no significant differences be tween controlled and compulsive subjects. The variables considered included: (1) current ease of obtaining opiates (X² [2] = 4.495, p = 0.14); (2) number of sources for obtaining opiates (t[89] = -.71, p = 0.48); (3) current dealing of any drugs (![]() [1] = 0.0, p = 1.00); (4) current dealing of opiates (

[1] = 0.0, p = 1.00); (4) current dealing of opiates (![]() [1] = 0.10, p = 0.92); (5) number of drug types currently used (t[40.5] = 0.98, p = 0.32); (6) number of drug types ever used (t[46.9] = 0.88, p = 0.39; (7) history of significant reduction or discontinuance of opiate use due to its unavailability (

[1] = 0.10, p = 0.92); (5) number of drug types currently used (t[40.5] = 0.98, p = 0.32); (6) number of drug types ever used (t[46.9] = 0.88, p = 0.39; (7) history of significant reduction or discontinuance of opiate use due to its unavailability (![]() [1] = 0.058, p = 0.81); and (8) history of significant increase in opiate use due to availability (

[1] = 0.058, p = 0.81); and (8) history of significant increase in opiate use due to availability (![]() [1] = 1.508, p = 0.23). In short, in terms of access to opiates, the controlled and compulsive subjects were equally at risk in relation to losing or gaining control over their drug use. These negative findings are among the most important results of our research because questions about availability are crucial to any theory of controlled use as well as to the development of public policy toward drug use.

[1] = 1.508, p = 0.23). In short, in terms of access to opiates, the controlled and compulsive subjects were equally at risk in relation to losing or gaining control over their drug use. These negative findings are among the most important results of our research because questions about availability are crucial to any theory of controlled use as well as to the development of public policy toward drug use.

A corollary finding concerned the method used to administer opiates. Analysis of several relevant variables did not support the view that compulsive users inject opiates and controlled users do not. There were no significant differences between these groups as to whether they currently injected opiates (![]() [1] = 0.903, p = 0.342), whether they injected heroin (

[1] = 0.903, p = 0.342), whether they injected heroin (![]() [1] = 0.536, p = 0.46), or whether they had ever injected opiates (

[1] = 0.536, p = 0.46), or whether they had ever injected opiates (![]() [1] = 0.352, p = 0.55). In fact, for all three variables the direction of difference was the opposite of what might have been expected, showing that a greater proportion of controlled subjects than compulsives actually injected the drugs.

[1] = 0.352, p = 0.55). In fact, for all three variables the direction of difference was the opposite of what might have been expected, showing that a greater proportion of controlled subjects than compulsives actually injected the drugs.

It was also assumed for the purpose of analysis that controlled users tended to use "softer" opiates, such as Percodan or codeine, for which addiction would develop more slowly, and that compulsives tended to use "hard" opiates like heroin, morphine, or Dilaudid. Again, however, the data did not support the supposition. When controlled and compulsive users were compared as to whether they were using or had ever used seven different opiates, all but two of the fourteen comparisons proved not significant at p ? 0.10. The two differences turned out to be artifacts resulting from the use of methadone by subjects who had been in methadone treatment programs. And when the type of opiate was dichotomized into "hard" (heroin, morphine, Dilaudid, methadone) and "soft" (codeine, Percodan), no significant differences were found between controlled and compulsive subjects in relation to the following relevant variables: whether they were using "hard" opiates (X2[1] = 0.012, p = 0.91); whether they were using "soft" opiates (![]() [1] = 0.000, p = 1.0); whether they had ever tried a "hard" opiate (

[1] = 0.000, p = 1.0); whether they had ever tried a "hard" opiate (![]() [1] = 0.000, p = 1.0); and whether they had ever tried a "soft" opiate (

[1] = 0.000, p = 1.0); and whether they had ever tried a "soft" opiate (![]() [1] = 0.000, p = 1.0).

[1] = 0.000, p = 1.0).

Finally, with reference to drug variables, analysis showed no significant differences between controlled and compulsive users over a wide range of variables relating to the circumstances of early opiate use. These variables included: (1) whether first opiate use had occurred alone or with others (![]() [1] = 0.000, p = 1.0); (2) positive versus negative or equivocal reaction to first use (

[1] = 0.000, p = 1.0); (2) positive versus negative or equivocal reaction to first use (![]() [1] = 0.033, p = 0.86); (3) age at first use (t[43.9] _ -.37, p = 0.71); (4) age when opiates were first purchased (t[42.5] = -0.70, p = 0.49); (5) number of tries before a "high" was achieved (t[83] = 0.72, p = 0.48); and (6) number of other drugs used prior to or concurrently with first opiate use (t[89] _ -0.04, p = 0.97).

[1] = 0.033, p = 0.86); (3) age at first use (t[43.9] _ -.37, p = 0.71); (4) age when opiates were first purchased (t[42.5] = -0.70, p = 0.49); (5) number of tries before a "high" was achieved (t[83] = 0.72, p = 0.48); and (6) number of other drugs used prior to or concurrently with first opiate use (t[89] _ -0.04, p = 0.97).

All these findings overturn, or at least are inconsistent with, arguments that are sometimes used to explain why it is that controlled opiate users exist, arguments that flow from current prohibitionistic policy. Neither availability of opiates, method of administration, type of opiate used, nor early experience with opiates served to distinguish our controlled subjects from our compulsive subjects.

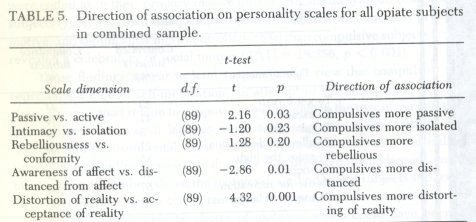

SET VARIABLES. Five personality scales were used in this study: (1) pas sive versus active; (2) intimacy versus isolation; (3) rebelliousness versus confor mity; (4) awareness of affect versus distance from affect; and (5) distortion of reality versus acceptance of reality. Each personality scale was scored from one to six points on the basis of material taken from each subject's interview. The results of all opiate subjects in the combined sample, displayed in table 5, indicate that the direction of association was as expected. Three results were significant at p <_ 0.03, indicating that the compulsives were more passive, more distanced from affect, and more distortive of reality than the controlled subjects.

Other findings on personality dealt with variables that have frequently been taken as indications of early personality deficits, such as criminal and delinquent behavior and unusually difficult family background. The tests administered showed no significant differences between controlled and compulsive users at age eighteen or younger in relation to the following factors: (1) catastrophic family difficulty, such as death of parent or parental divorce (![]() [1] = 0.454, p = 0.50); (2) significant violence in family (

[1] = 0.454, p = 0.50); (2) significant violence in family (![]() [1] = 0.242, p = 0.62); (3) parental discipline, whether strict, moderate, or lax (

[1] = 0.242, p = 0.62); (3) parental discipline, whether strict, moderate, or lax (![]() [2] = 1.73, p = 0.42; (4) history of trouble in elementary school and through high school (

[2] = 1.73, p = 0.42; (4) history of trouble in elementary school and through high school (![]() [1] = 0.954, p = 0.33); (5) relationship to father while growing up (

[1] = 0.954, p = 0.33); (5) relationship to father while growing up (![]() [1] = 2.798, p = 0.25); and (6) alcohol- or drug-abusing parent (

[1] = 2.798, p = 0.25); and (6) alcohol- or drug-abusing parent (![]() [I] = 0.324, p = 0.57).

[I] = 0.324, p = 0.57).