|

This paper reviews the research literature on the utility of the female condom as an HIV risk reduction device, and provides preliminary data on the acceptability of the female condom among women with a number of HIV risk behaviors. The female condom appears promising if for no other reason than it increases the available options for risk reduction, since the only alternative is the traditional male condom. Clinical studies have established that the female condom is impermeable to HIV, and provides significandy lower risk of bacterial and/ or viral infections. Further, the female condom is primarily woman-controlled, so women are not as dependent on the cooperation of sex partners to protect themselves from HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases. Other advantages are that it is stronger than a traditional male condom thereby reducing the risk of rupture, it causes less loss of sensitivity, it permits penetration before complete erection of the penis, and it permits continued intimacy in the resolution phase of intercourse since it need not be removed immediately.

Focus groups were conducted with women with identifiable risk behaviors in three sites. The focus groups suggest that if women (and men) can get over their initial reluctance to try this "funny looking" new device, they like it! Preliminary data from another study of women with multiple HIV risk behaviors found that the majority of the women who used the female condom during sex rated it more favorably than the male condom. Their partners also rated the female condom favorably. Although the female condom will require a period of habituation and will still not appeal to all, there appears to be general acceptance among a wide variety of individuals, including those with a range of HIV risk behaviors.

The Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) estimated that some 20.1 million adults were living with HIV infection or AIDS worldwide as of the end of 1995, including 9 million women. The United States has the largest number of AIDS cases in the industrialized world — approximately 750,000 based on UNAIDS estimating techniques, and 513,486 as of December 1995, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). In the United States, women are the fastest growing population to be infected by HIV (CDC 1995), although men who have sex with men continue to represent the largest number and proportion of persons estimated to have AIDS. The most common forms of exposure among women were injecting drug use (41 percent) and heterosexual contact with a partner who was at risk high (38 percent)—an injection drug user or one known to have HIV infection (CDC 1995).

The risk factors associated with HIV acquisition and transmission specific to women are multiple and interrelated, particularly for women who use drugs (Rosenberg and Weiner 1988). Injection drug use is, of course, a major HIV risk factor. Higher levels of unsafe sex associated with drug use also increases the potential for infection through sex with injection drug users (Padian et al. 1987; Schilling et al. 1991a), sex for crack exchanges (Goldsmith 1988; Campbell 1991; McCoy and Inciardi 1993; Inciardi, Lockwood and Pottieger 1993), and sex with numerous anonymous partners (Plant et al. 1989; Inciardi, Lockwood and Pottieger 1993). In fact, studies indicate that drug use may overshadow sexual activity as a risk factor for HIV (McCoy and Inciardi 1993; Rolfs, Goldberg and Sharrar 1990; Fullilove et al. 1990a; Mantell, Schinke and Akabas 1988; McCoy et al. 1990; Rosenberg and Weiner 1988). Women who are dependent on trading sex to support themselves increase their risk of HIV acquisition (Worth 1989; Campbell 1991).

For women who become injecting drug users (IDUs), the risk of HIV infection tends to be particularly high. Females appear to be more likely to inject in social settings, and inject after their partner. And although the majority of IDUs are men, the majority of those males have their primary sexual relationships with females who are not IDUs. Female IDUs who engage in prostitution to help support their drug habit are also a means of heterosexual transmission of HIV, although this type of transmission has not occurred nearly as frequently as transmission from a male IDU to female non-IDU within a regular, long-term relationship.

HIV infection is increasingly a disease of poverty with disproportionately high rates of infection found among minorities. Although black and Hispanic women constitute 21 percent of all U.S. women, about 76 percent of AIDS cases reported among women in 1995 occurred among blacks and Hispanics. In 1995, for the first time, equal proportions of persons reported with AIDS were black and white (40 percent). In 1995, 84 percent of the children with AIDS were black or Hispanic (CDC 1995).

For many women of color, particularly those of low socioeconomic status, AIDS is only one of many life problems. The possibility of HIV infection appears to be of less concern to those at-risk than other immediate financial concerns, including housing and legal problems. They often rate it as being less serious than unemployment, lack of access to child care, and crime victimization (Kalichman, Hunter and Kelly 1992). Most worry more about the practicalities of daily survival than the eventual consequences of HIV infection. Further, the fear of relationship loss is more operant in the health beliefs and actions of the majority of women, than the fear of infection (Shervington 1993).

The typical problem for women is that the only proven method of HIV prevention — consistent use of a male condom — requires the cooperation of the male partner. One reason for the increased risk faced by women of lower socioeconomic status is that condom use is partially determined by poverty and culture (Roper, Peterson and Curran 1993). The ability ofwomen to negotiate for safer sex practices, i.e., insist on condom use, are lower in cultures where women occupy lower social positions (and this is still true in the United States). The ability of sex workers to negotiate for condom use is expected to be lower yet, especially since sex work is illegal and carries with it few social or legal rights. Also, negotiating for condom use with a client under the influence of alcohol or other drugs may introduce further complications and the risk of violence.

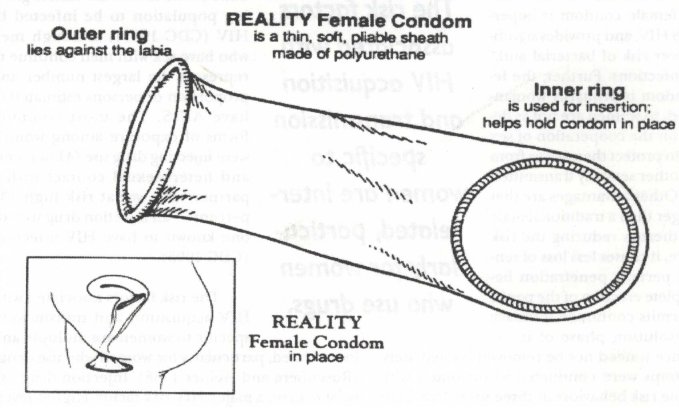

Women have few HIV risk reduction options under their direct control. Although sponges and diaphragms are promoted as HIV risk reduction mechanisms because they reduce the incidence of STDs (Rosenberg and Gollub 1992b), neither has actually been tested in terms of HIV infection-risk reduction. It is therefore essential to develop and promote an effective woman-controlled risk reduction method to reduce HIV acquisition and transmission (Carovano 1990; Lancet 1990; Gollub and Stein 1993; Institute of Medicine 1994). The Reality™ Vaginal Pouch, or simply, the female condom, holds considerable promise in expanding the HIV risk reduction options for women. First marketed in the United Kingdom in September 1992, the female condom received FDA approval in the United States in 1994. The female condom has been marketed by Wisconsin Pharmacal (recently bought out by the Female Health Co.) under the name of Reality, since August 1994. The RealityTM female condom is a polyurethane sheath with a flexible inner ring which secures the condom against the cervix and an outer ring which prevents the condom from entering the vaginal canal. The design combines features of the male condom and the diaphragm (Bounds et al. 1988).

The female condom has several advantages over the male condom as an HIV risk reduction devise. As mentioned above, it puts women more in control since it is worn by women. Nevertheless, it's use does generally require male cooperation, although one small study (n=24) of female sex workers in Mexico found they were able to conceal the condom from their clients by pushing the outer ring up into the vagina and pulling it out just before intercourse (Hernandez-Avila 1992). In a study of over 200 Puerto Rican women, the female condom was thought to offer protection primarily because the womén believed they would be able to negotiate and control its use (Gil 1995). About three-quarters (78.5 percent) said they were somewhat willing or willing to discuss the use of the female condom with their partners. This percentage seems high in that Hispanic men's assertive role in sexual negotiation is well-documented. It is believed that requesting condom use undermines authority and promotes infidelity (Gil 1995). However, the women seemed to feel they would be willing to try the female condoms themselves, even though they might not be willing to suggest male condom use to their partners.

Another advantage is the female condom can be inserted up to eight hours before intercourse, which can be a real advantage for women sex workers or those heavily drug involved (i.e., it can be inserted before they get high and their judgment is impaired). It can also protect women from infections from pre-ejaculated fluids. Because the female condom covers both the internal and external genitalia, it provides greater protection against STDs. The female condom covers the entrance to the vagina where STD lesions may be found and the urethra which may be an entrance to infection, and it covers the base of the penis during intercourse (Leeper and Conrardy 1989). In addition, because the female condom is made of polyurethane, which is 40 percent stronger than a male latex condom, it has less risk of rupture than the male condom (Bounds et al. 1988; Bounds 1989; Leeper and Conrardy 1989; Gollub and Stein 1993; Farr et al. 1994). Polyurethane also transfers heat much more readily than latex, making it more comfortable. Other advantages are that because of its loose fit, it causes less loss of sensitivity, it permits penetration before complete erection of the penis, and it permits continued intimacy in the resolution phase of intercourse since it need not be removed immediately (Bounds et al. 1988).

Clinical studies have established that the female condom is impermeable to HIV (Drew et al. 1989, Voeller 1991) or cytomegalovirus (Drew et al. 1989), and provides significantly lower risk of bacterial and/or viral infections (Bounds 1989; Soper, Brockwell and Dalton 1991; Soper et al. 1993). In a leak test where condoms were tested for pin holes and tears during manufacturing, RealityTM received a .6 percent leakage rate compared to a 3.5 percent leakage rate for the male condom. In another leak test measuring spillage during use, RealityTM had a 2.7 percent vaginal exposure rating whereas the male condom had a 8.1 percent rating (Leeper and Conrardy 1988; Leeper 1990). RealityTM has also been found to have no effect on resident bacteria flora and there is no evidence of lower genital tract trauma during intercourse when RealityTM is used (Soper, Brockwell and Dalton 1991). In terms of pregnancy, clinical trials conducted in the United States and abroad have found the female condom to provide contraceptive efficacy in the same range as other barrier methods (Farr et al. 1994; Trussell et al. 1994).

Several studies have tested the acceptability of RealityTM among both women and men and found that the majority of both women and men had favorable reactions to the female condom (Gollub, Stein and El-Sadr 1995; Gil 1995; Farr et al. 1994). Of 24 couples studied in the United Kingdom, 67 percent of the women and 83 percent of the men found the female condom easy to use; 50 percent of the women and 54 percent of the men found it an acceptable contraceptive and HIV/STD prevention method; and 50 percent of the women and 37 percent of the men preferred it to the male condom (Schilling et al. 1991). In a study of 294 U.S. women, 73 percent found RealityTM easy to use, 56 percent considered it an acceptable contraceptive, and 82 percent found it an acceptable HIV/STD prevention method (Schilling et al. 1991). Gollub, Stein and El-Sadr (1995) also found that their study's respondents had favorable attitudes toward RealityTM. The 52 respondents 87 percent Black and 12 percent Hispanic) overall reaction to the condom was extremely positive, with a mean score of 1.1 (0=liked very much, 4=disliked very much). In addition, the respondents were asked to rate their partners' reactions, and nearly half (49 percent) reported that their partner liked the female condom.

To date, only a few studies of the acceptability of the RealityTM female condom have been conducted among women at high risk for HIV. In Thailand, for example, 20 sex workers were educated about and given female condoms. The female condom was used in 32 percent of all sexual encounters and male condoms in 35 percent of sexual encounters. Almost all the women — 90 percent — said they would recommend the female condom to friends (Sakondhavat 1990). A study involving 46 sex workers in Malawi (Africa) found that 91.3 percent liked the female condom very much, and 8.7 percent liked it fairly well. 93.5 percent said they liked it more than the male condom, with the most frequent reason cited for liking the female condom was that it gave them personal control/power. 97.8 percent of the sex workers said they would use the female condom again (Blogg 1994).

Focus Groups among High Risk Women

Since little research has been conducted on the acceptability of the female condom among high-risk groups, particularly in the United States, University of Delaware staff worked with colleagues at two additional sites (St. Louis and North Carolina) in conducting focus groups of women with multiple HIV risk behaviors. The focus groups in St. Louis and North Carolina included women respondents enrolled in the National Institute on Drug Abuse's (NIDA's) Cooperative Agreement for AIDS Community-Based Outreach/Intervention Research. The focus group in Delaware included all African-American women who were recruited either from ongoing studies of ex-offenders, or who had been treated in a public health clinic for STDs. In each site, a series of two focus groups were held. In the first session, women were introduced to the female condom and then asked to discuss their initial reactions to the device. Women were then instructed on the use of the female condom and their reactions were again sought. Each woman was given six condoms, a bottle of lubricant, and an instructional brochure. The women were asked to try the female condoms, and return in two weeks to discuss their experiences—both positive and negative.

A total of 30 women participated in the first session across the 3 sites, and 28 returned for the follow-up sessions. The women in the Cooperative

Agreement sites had heard about the female condom because it is introduced in the "Standard [HIV] Intervention." However, female condoms are not made available to the women and no one had tried a female condom. These women's initial reactions were surprise and laughter at the sight of the condom. They thought it was very big, and wondered how it fit inside a woman's body. They were concerned that it could get lost inside them. The women also didn't like the idea of the outer ring of the female condom hanging outside their body.

The women's opinions changed over the course of the initial focus group, and they vocalized increasing acceptance of trying the female condom. There were mixed comments about women's willingness to put their finger in their vagina to insert the condom, but most women reported they used tampons, although several indicated they had discontinued their use because they found them uncomfortable. Virtually all the women had tried male condoms, with various levels of satisfaction reported. The consensus at the end of the focus groups seemed to be that although this condom is "new and funny looking," it has potential and we would like to try it.

In total, 16 women (53.3 percent) across the three sites reported trying the female condom. Most of women used at least two of the condoms, but no one used more than four. Most of those who did not try them reported not having the opportunity to do so because they had not had sex, although a few women reported their partners were unwilling to try them. A few women in each group passed along female condoms to friends, and returned to the group with stories about those experiences. These women seemed to relish the role of being "gatekeepers," and passing along the female condoms to others with instructions for their use. These gatekeepers said the women they shared them with really liked the condoms.

Virtually all of the women reported difficulty inserting the female condom the first time because the lubrication made it slippery and difficult to grasp. However, most women said it was easier to insert the second time. Overweight women reported difficulty inserting the female condom, but one woman said she dealt successfully with this by letting her husband insert it. She reported this enhanced their sexual enjoyment.

Most of the women introduced the female condom to their partners by explaining what it was and showing them the instructional brochure. Some also showed the condom to their partner and allowed him to feel it and react to it. The women did not necessarily have uniform experiences with the female condom during sexual encounters. While the majority were pleased with their experiences, and nearly all stated they would be willing to use the female condom again, not all had positive reactions. However, most of the negative impressions were from those who didn't actually try the female condom.

Most women reported they liked the female condom because it allowed for greater stimulation, warmth, and empowerment for them and less restriction for their male partner. Several women reported that neither they nor their partner felt the female condom while having intercourse—although nearly an equal number said their partner reported reduced sensation. Many women reported their partners generally liked the female condom, and most felt it superior to the mâle condom. One woman in Delaware was especially adamant about her positive experiences—stating that the female condom enhanced both her's and her partner's enjoyment. They both reported extra stimulation. The enthusiasm of this woman was infectious, and even those women who reported less than positive reactions to the female condom seemed inspired to give them another try.

The "gatekeeping" phenomenon mentioned earlier was unanticipated. What was especially surprising was that a few women in each of the focus groups reported sharing their supply of female condoms with friends. The women said it was good to know there was another alternative to the male condom for HIV and STD prevention, and several suggested that they would like to pass out these condoms to women sex workers that they knew. These gatekeepers obviously thought it important to give women alternatives, especially those they viewed as "high risk," and gladly accepted the role when it was made available by virtue of arming them with some knowledge and a small supply of female condoms. It's too early for there to be much "common wisdom" about the use of the female condom, and the early information funneled through gatekeepers will be critical in it's acceptance.

A consensus reached in each focus group was that more experience with the female condom would help to increase its acceptance. The women felt that the introduction they had received to the product made a big difference. They felt it would be difficult for women to use the female condom with only the instructions that are packaged with the product on store shelves. Because the female condom is new and different, it will take some getting used to. The women felt that it is critical to have someone demonstrate and explain how to use the device.

The experience with the focus groups led the to recognition of the importance of an instructional/counseling intervention of the female condom to high-risk populations. Precisely because it is "funny looking," and a new device, it will require a period of learning, especially among women who have difficultly touching their genitalia or poor knowledge of their anatomy. There is also the difficulty of sexual negotiation. Most of the women enrolled in the Focus Groups who used the female condoms were in monogamous relationships, hence they experienced little difficulty in negotiating the use of the female condom. However, even so, a few of the women reported their partners refused to try the female condoms.

The University of Delaware has also been involved in a conducting a research study on the acceptability of the female condom among women being released from jail and prison within Delaware. Women participate in a 20-hour course designed to educate them about HIV risks, in which the female condom is introduced. Participants have access to free female and male condoms for a one year period following their release from incarceration at six distribution sites throughout the state. Early follow-up data on 28 women who had been released in the prior two months, shows that 22 of these women have had sex. Seventeen of these 22 women have used the female condom—with one indicating that she has used 100 female condoms. Of the 20 who report having vaginal sex with their husband or boyfriend, 15 have used the female condom—and five women report using the female condom every time they had sex with their husband or boyfriend. Thirteen women reported using a male condom with their husband or boyfriend, and four reported using a male condom every time they had sex. Of the four women who reported having vaginal sex with a friend or acquaintance, two have used the female condom and three have used male condoms. Two women reported having sex with a stranger, one who reported using a female condom some of the time, and the other reported using male condoms every time she had sex with a stranger.

Fourteen of the 17 women using female condoms said their partners liked the female condom, and 12 women said their partner liked it better than a male condom. Only two women said their partners had strong objections to using the female condom. Overall, 71 percent of the women using the female condom said they were very satisfied with it, and 7 percent said they were somewhat satisfied. Another 14 percent said they were neutral, and only 7 percent were very dissatisfied. While these data are preliminary, they suggest that women (and men) like the female condom!

Research suggests promising results and acceptability of the female condom among diverse populations with varying sexual histories. However, these studies have been on a small scale, and additional data are needed to further test the acceptability of female condom use. The study currently being conducted by the University of Delaware will provide additional data on the acceptability among women at high risk for HIV infection, such as sex workers, IDUs, or those who exchange sex for drugs. Not all people with identifiable HIV risk behaviors will like the female condom, but it appears that there is acceptability for this product among high risk groups.

NIDA's AIDS projects as well as other HIV/ AIDS education efforts have documented the difficulty involved in getting women to participate in HIV prevention and education efforts (Flaskerud and Nyamathi 1990; McCoy et al. 1990; Weissman 1991). Therefore, many HIV education projects have had limited success in reaching the women in greatest need of risk reduction initiatives. Cultural norms of female submission and passivity in sexual negotiation is a major barrier to preventive actions. However, women express enthusiasm for female condom because it allows them greater control over safe-sex practices. Like any new method, it will require a period of learning and habituation (Gollub and Stein 1993), but there is evidence suggesting that it will be accepted by many of those with identified HIV risk behaviors. •

Lana Harrison, PhD, is the associate director of the Centerfor Drug and Alcohol Studies at the University of Delaware, 77 E. Main St., Newark, DE 19716, tel: (302) 831-6113.

REFERENCES

Blogg, Suzanne and James Blogg. 1994. "Acceptability of the Female Condom (Femidon) within a Population of Commercial Sex Workers and Couples in Salima and Nkhotakota, Malawi." Family Health International, Research Triangle Park.

Bounds, Walli, John Guillebaud, Laura Stewart, and Stuart Steele. 1988. "A Female Condom (Femshield): A Study of its User Acceptability." British Journal of Family Planning 14:83-87.

Bounds, Walli. 1989. "Male and Female Condoms." British Journal of Family Planning 15:14-17.

Campbell, Carole A. 1991. "Prostitution, AIDS, and Preventive Health Behavior." Social Science Medicine 32:1367-1378.

Carovano, Kathryn. 1990. "More Than Mothers and Whores: Redefining the AIDS Prevention Needs of Women." International Journal of Health Services 21:131-142.

Centers for Disease Control. 1995. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report 7(2).

Drew, W. Lawrence, Margaret Blair, Richard C. Miner, and Marcus Conant. 1989. "Evaluation of the Virus Permeability of a New Condom for Women." Unpublished Manuscript from the Mount Zion Hospital and Medical Center, Biskind Pathology Research Laboratory, San Francisco, CA; and the University of California San Francisco.

Farr, Gaston, Henry Gabelnick, Kim Sturgen and Laneta Dorfinger. 1994. "Contraceptive Efficacy and Acceptability of the Female Condom." American Journal of Public Health 84:1960-1964.

Fullilove, Robert, Mindy Thompson Fullilove, Benjamin Bowser, & Shirley A. Gross. 1990. "Risk of Sexually Transmitted Disease Among Black Adolescent Crack Users in Oakland and San Francisco." Journal of the American Medical Association 263:851- 855.

Gil, Vincent E. 1995. "The New Female Condom: Attitudes and Opinions of Low-Income Puerto Rican Women at Risk for HIV/AIDS." Qualitative Health Research 5 (2) :178-203.

Gollub, Erica L., and Zena A. Stein. 1993. "Commentary: The New Female Condom - Item I on a Women's AIDS Prevention Agenda." American Journal of Public Health 83:498-500.

Gollub, Erica L., Zena A. Stein, and Wafaa El-Sadr. 1995. "Short-Term Acceptability of the Female Condom Among Staff and Patients at a New York City Hospital." Family Planning Perspectives 27 (4) :155-158.

Goldsmith, Marsha F. 1988. "Sex Tied to Drugs =STD Spread." Medical News and Perspectives 260:2009.

Inciardi, James A., Dorothy Lockwood, and Anne E. Pottieger. 1993. Women and Crack-Cocaine. New York: Macmillan.

Institute of Medicine. 1994. AIDS and Behavior: An Integrated Approach. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Kalichman, Seth C., Tricia L. Hunter, and Jeffrey A. Kelly. 1992. "Perceptions of AIDS Susceptibility Among Minority and Nonminority Women at Risk for HIV Infection." Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 60:725-732.

Lancet. 1990. "Barriers and Boundaries." The Lancet 335:1497-1498.

Leeper, Mary Ann. 1990. "Preliminary Evaluation of REALITY", A Condom for Women to Wear." AIDS Care 2:287-290.

Leeper, M.A. and M. Conrardy. 1989. "Preliminary Evaluation of REALITY": A Condom for Women to Wear." Advances in Contraception 5:229-235.

Mantel!, Joanne E., Steven P. Schinke and Sheila H. Akabas. 1988. "Women and AIDS Prevention." Journal of Primary Prevention 9:1-2.

McCoy, H. Virginia and James A. Inciardi. 1993. "Women and AIDS: Social Determinants of Sex-Related Activities." Women and Health 20:69-86.

McCoy, H. Virginia, Carolyn Y. McKay, Lisa Hermanns and Shenghan Lai. 1990. "Sexual Behavior and Risk of HIV Infection." American Behavioral Scientist 33:432-450.

Padian, Nancy S. 1988. "Prostitute Women and AIDS: Epidemiology." AIDS 2:413-419.

Plant, Moira L, Martin A. Plant, David F. Peck and Jo Setters. 1989. "The Sex Industry, Alcohol and Illicit Drugs: Implications for the Spread of HIV Infection." British Journal of Addiction 84:53-59.

Rolfs, Robert T., Martin Goldberg, and Robert G. Sharrar. 1990. "Risk Factors for Syphilis: Cocaine Use and Prostitution." American Journal of Public Health.

Roper, William L., Herbert B. Peterson and James W. Curran. 1993. "Commentary: Condoms and HIV/STD Prevention - Clarifying the Message." American Journal of Public Health 83 (4) :501-503.

Rosenberg, Michael J., and Erica L. Gollub. 1992b. "Commentary: Methods Women Can Use That May Prevent Sexually Transmitted Disease, Including HIV." A mericanJournal of Public Health 82:1473-1478.

Rosenberg, Michael J. and Jodie M. Weiner. 1988. "Prostitutes and AIDS": 78:418-423.

Sakondhavat, C. 1990. "Further Testing of Female Condoms." British Journal ofFamily Planning 15:129.

Schilling, Robert F., Nabila El-Bassel, Mary Ann Leeper and Linda Freeman. 1991. "Acceptance of the Female Condom by Latin- and African-American Women." American Journal of Public Health 81:1345-1346.

Shervington, Denese. 1993. "The Acceptability of the Female Condom among Low-Income African-American Women." Journal of the National Medical Association 85 (5) :341-347.

Soper, David, E., Nancy J. Brockwell, and Harry P. Dalton. 1991. "Evaluation of the Effects of a Female Condom on the Female Lower Genital Tract." Contraception 44:21-29.

Soper, David E., Donna Shoupe, Gary A. Shangold, Mona M. Shangold, Jacqueline Gutmann and Lane Mercer. 1993. "Prevention of Vaginal Trichomoniasis by Compliant Use of the Female Condom." Sexually Transmitted Diseases 20:2-12.

Trussell, James, Kim Sturgen, Jennifer Strickler and Rosalie Dominik. 1994. "Comparative Contraceptive Efficacy of the Female Condom and Other Barrier Methods." Family Planning Perspectives 26:66- 72.

Worth, Dooley. 1989. "Sexual Decision-Making and AIDS: Why Condom Promotion Among Vulnerable Women is Likely to Fail." Studies in Family Planning 20:297-307.

|