|

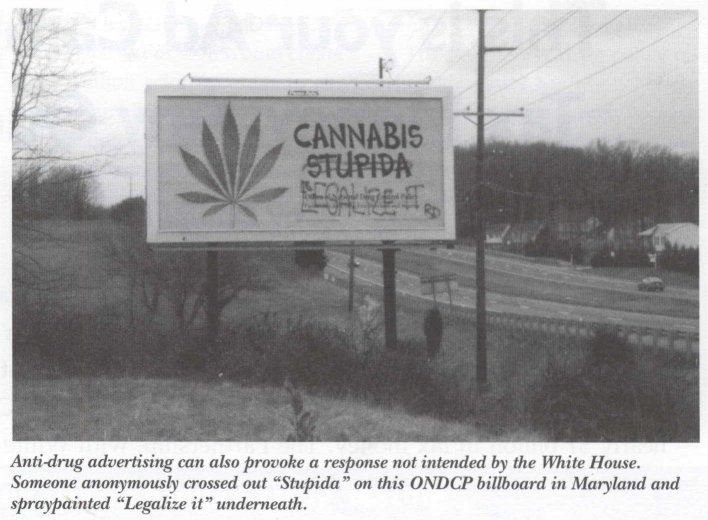

Piggybacking on the Partnership for a Drug-Free America's decade-old ad campaign, the White House has committed $195 million in 1998 for an anti-drug media campaign that went nationwide on July 9. The White House Office of National Drug Control Policy wants Congress to continue to fund its National Youth Anti-Drug Media Campaign over the next four years — nearly $1 billion in tax money. The Partnership, with White House oversight, will generate advertising that targets young people and parents with four or more anti-drug impressions a week.

The media — especially broadcasters, but also newspapers, billboards, home videos, and the Internet — will be de facto required to donate free equivalent time and space for every ad purchased for the campaign. Over five years, that's close to another $1 billion on top of the almost $3.3 billion donated for PDFA ads from 1987 to 1997. And, starting this fall, the ONDCP anticipates that nonmedia companies will provide fast-food tray liners, sporting event tie-ins, and anti-drug tag lines in a corner of their own ads, to name a few such efforts.

The White House will also try to influence the content of movies, music, and television programming; it's already met with major Hollywood studio heads and the Writers', Actors', and Directors' Guilds, according to ONDCP senior adviser Alan Levitt. Programming could conceivably count as a match, Levitt said, so broadcasters might increase revenues by airing the appropriate anti-drug story lines in lieu of donating ad time.

This brings the grand total to $5 billion, including the projected $1 billion in public funding for a previously private campaign. What evidence is there that the advertising works to make kids put down or never pick up a joint or tube of glue?

The PDFA formally cites three pieces of work. But, as I reported in the April 27 edition of Brandweek magazine, one of the researchers, though ultimately standing behind her article, has expressed grave doubts about the research techniques. The other researchers have yet to publish their studies; by the peer-review standards of academia, their work is still aborning.

Dr. Evelyn Cohen Reis, then a fellow at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, was lead author of a December 1994 article — her only drug-use study — published in the Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Interviewed recently, she said, "You can't tell, based on the paper, that it [the advertising] actually works." She added, the study "being entirely self-reported is a huge limitation. I think they [her respondents] were telling us what they thought we wanted to hear."

As Reis explains: "It's called 'socially desirable' answers. My concern is the kids thought they were supposed to say the ads work, the younger kids more so." Asked whether there was "any validity" to her published claim on the ads' deterrent effect, she said she didn't know. She added, "You can't prove it either way, whether they're just saying the 'right' thing."

Reis ultimately did not repudiate her paper. She said, "My opinion is that we know children and adults are influenced by advertising, so it makes sense that the PDFA ads work" [emphasis added].

Reis's co-author, Dr. Hoover Adger Jr., is current deputy director of the ONDCP. In response to Reis's remarks, Adger said, "You can't get into cause and effect in any self-reported [behavior] study." He defends the ads' efficacy, but cited no published work other than Reis's to bolster that contention. The PDFA's acting research chief expressed surprise at Reis's statements, but declined further comment.

Research by Professor John K. Worden of the University of Vermont College of Medicine accentuates Reis's doubts about self-reporting. To study anti-tobacco advertising, he put cotton balls in his youthful respondents' mouths, warning he was checking to see if they'd been smoking. Led to believe lying was futile, they admitted to a 30 percent higher self-reported smoking rate.

The second paper the PDFA cites has yet to be published. Its lead author, Lauren G. Block, assistant professor of marketing at New York University, has recently withdrawn it from consideration to be revised with econometric input from a new collaborator. The PDFA knows this, but nonetheless cites her draft, which might not be resubmitted for another year.

Block is studying the PDFA's own data from its first six years of operation (1987 to 1992), involving some 8,000 respondents. Most were approached in malls, a questionable sampling technique — usually used by researchers with limited budgets — that the PDFA has since abandoned.

Asked about the accuracy of self-reported drug-use surveys, Block said: "People are somewhat accurate. With drug abuse, yes, there's a bias toward under-reporting. But they're fairly accurate."

Block finds patterns associating drug-use declines and advertising. But she writes, "[lit is possible that the observed decline could be partly or entirely attributable to other causes.... [O]ther variables such as discretionary income, parental control, and the price of different drugs could also influence drug behavior," as could "other anti-drug intervention programs in addition to their exposure to anti-drug advertising."

Third and finally, the PDFA cites University of Michigan professor Lloyd D. Johnston. A respected researcher, his annual teen survey, "The Monitoring the Future Study," receives national notice.

Johnston has included questions in his survey about the PDFA's ad campaign since its inception in 1987. But he has yet to publish the results formally; he'll do so in about a year.

When formally published, his data will indicate the PDFA ads have a considerable, if declining, deterrent effect. Johnston acknowledged, "It's very difficult to measure the effect of the ads; drugs are such a feature of the culture." And he cautions about "the fallacy of single causes. Advertising is only one, and not the strongest, influence." Federal money supports Johnston's surveys, and it has helped the PDFA evaluate its campaign since 1990 (according to Block).

With the federal government's large new ad campaign, the public is entitled to some accounting for the money spent as well as the reliance on PDFA ads. Given Reis's expressed doubts and Professor Block's recent retreat, it looks as though only the third, unpublished leg of PDFA's three-legged stool remains in place. But Johnston's work needs to see print to subject his work to outside analysis.

William DeJong of the Harvard School of Public Health, who consulted on the ONDCP paid campaign, said, "My fondest wish is to get these campaigns rigorously evaluated. I wish I could say we know for sure that they work, but I don't think I can say that." Adds Lawrence Wallack, professor of public health at the University of California, Berkeley, who met with ONDCP a year ago, "There's no solid data that show the media campaigns create meaningful changes in behavior."

What about results as measured in the real world? The media donated time and space to the PDFA worth $361 million in 1990, $367 million in 1991, $323 million in 1992, $305 million in 1993, and $295 million in 1994. Representatives of both the PDFA and the ONDCP said that the behavioral changes were expected to lag exposure to the ads by two or three years.

In 1992, Johnston's "Monitoring the Future Study" reported that illegal drug use increased among eighth graders, a trend that spread to tenth and twelfth graders and picked up speed in 1993. Note that 1991 was the ' peak year and yet, despite the supposed lag, drug use increased. Other surveys confirmed these increases, which now appear to be slowing down or reversing themselves. It looks like the Partnership picked a good time to be getting more publicity (and more money) for its ads. The question, however, remains: When will the public know whether the White House is making a sound investment with its $1 billion-plus campaign that relies on unproven techniques?

Daniel Forbes is a New York freelancer who writes on social policy issues. Forbes published an article based on his research in the April 27 edition of Brandweek magazine under his pen name, Daniel Hill.

|