Politics of Denial: White House

Keeping an Eye on America

Every year since 1989, the White House has told Congress what it plans to do in the field of drug policy by submitting a National Drug Control Strategy. And every year the opposition party has disparaged the Strategy, largely because Democrats and Republicans have different criteria for evaluating progress in the field. This year, the Clinton administration is trying to change that.

President Clinton and his top drug policy advisor, General Barry McCaffrey, unveiled the administration's latest Strategy on February 14. In it, they ask Congress for a record $17.1 billion for the 1999 fiscal year. But, more significantly, they propose a plan for decreasing illegal drug use and the availability of drugs by half over the next 10 years. By setting up a series of goals and benchmarks, Clinton has offered Congress a common frame of reference for evaluating drug policy.

How likely is the new 10-year plan and the increased spending to cut drug use in half? Not very. Presidents and drug czars routinely acknowledge that they alone cannot bring about the changes that they pitch to Congress and the voters. Drug demand and supply change according to many factors, not just according to government policy. But the new Strategy is worth exploring if only to see how it proposes reducing drug use to historic lows.

MORE SPENDING IN 1999

Since McCaffrey became director of the White House Office on National Drug Control Policy in 1996, President Clinton has increased both the office's funding and its staff dramatically. McCaffrey has brought new life to a once-marginalized post, and he now arguably rivals ONDCP's first director, William Bennett, for keeping drug policy in the national spotlight.

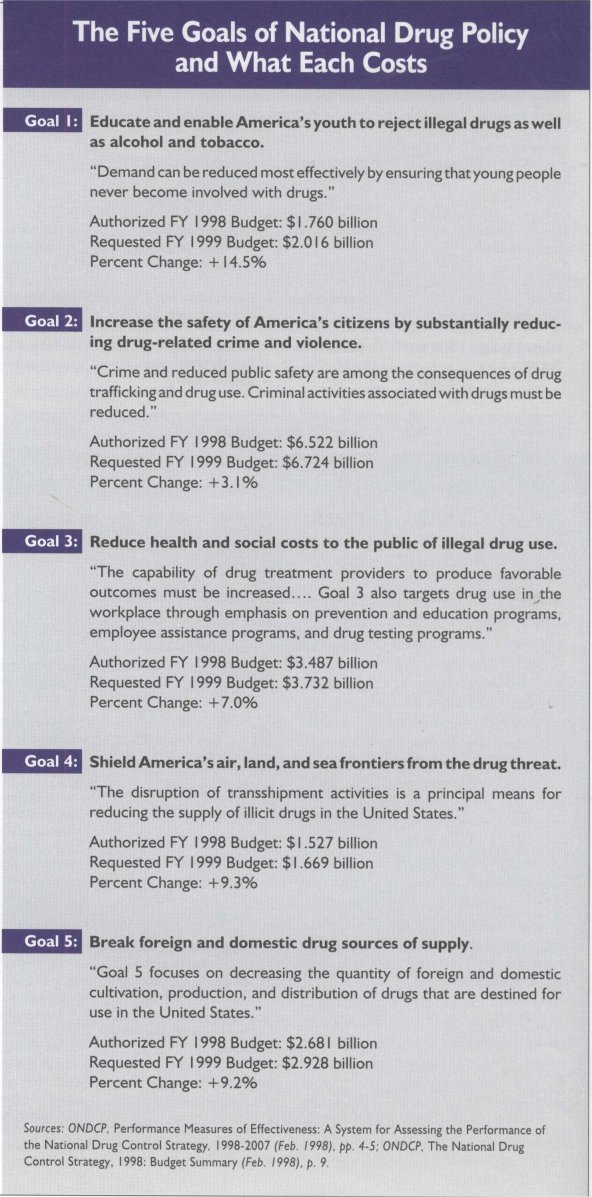

The 1999 budget of $17.1 billion is $1.1 billion (6.8 percent) more than the 1998 fiscal year. The money will go to over 50 federal departments and agencies —34 percent allocated to demand reduction, 66 percent to supply reduction. McCaffrey, however, does not agree with the simple demand/supply split and last year introduced five Strategy Goals (see Box, page 12) to characterize, the administration's priorities.

This Strategy makes a valiant attempt to predict and manipulate the variables in drug policy. The five main Goals are backed up by 32 supporting objectives. Both the Goals and objectives will be tracked by 94 performance measures or targets, which will tell policy-makers where they should be at certain points between now and 2007. As we will see, the Strategy will attempt a two-pronged approach to reach its ultimate goal, cutting drug use in half.

HOW REALISTIC A STRATEGY?

In theory, the Strategy's complexity means that policy-makers will be paying attention to many different indicators, which can be improved or changed along the way. However, a major limitation is that ONDCP has included unquantifiable measures that reflect political rhetoric more than achievable benchmarks.

For example, Goal 2, Objective 5, "Break the cycle of drug abuse and crime," is important, but the only thing ONDCP wants measured and reduced is the number of inmates who test positive for drugs. The Strategy ignores the fact that prisoners still have access to drugs, a serious flaw in the policy especially for politicians who routinely promise to make some part of the country or another permanently "drug-free." This objective further implies that crime is a direct result of drug abuse. There is an association between the two (besides the fact that any involvement with illegal drugs is a crime), but it misses the point that the black market is a great source of crime — for economic reasons, not for pharmacological ones. Needless to say, the federal government is not interested in addressing the downside of prohibition, so any involvement with drugs counts as a crime, even when no one or no thing is injured or destroyed.

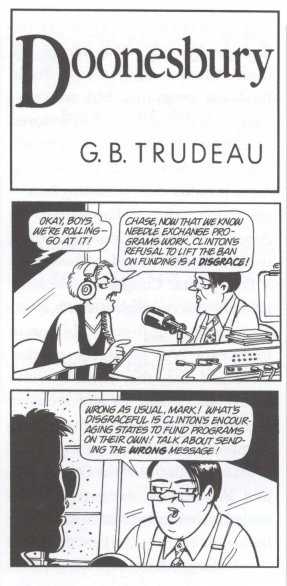

Another example of how the Strategy is unrealistic is in Goal 3, Objective 2, which mandates the reduction of "drug-related health problems with an emphasis on infectious disease." Yet, the goal nowhere mentions syringe exchange programs in its HIV or hepatitis sections. This omission is not surprising. McCaffrey convinced Clinton in April to continue the ban on federal funding for such programs, even as the administration acknowledged that exchanges reduce the spread of blood-borne diseases without increasing drug use. Because the White House is afraid of "sending the wrong message" (McCaffrey's words), this objective is nothing more than an empty promise.

These and other objectives in the Strategy have been long-time drug policy goals, but they also reflect the deep-seated belief among politicians that doing more of the same will eventually work. They ignore the stubbornness of the economic laws behind the drug trade and fail to appreciate the inventiveness of both suppliers and users of illegal drugs to circumvent government enforcement.

THE STRATEGY'S CHIEF MEASURE

Goal 1, Objective 8 reads: "Support and disseminate scientific research and data on the consequences of legalizing drugs." This objective has measurable tasks — developing information packets and sending them out — but it is not clear why young people would be more likely to "reject illegal drugs" because of these efforts. The objective here is not "scientific" or "data-driven." Rather it is an attempt to change attitudes.

This objective highlights an important aspect of ONDCP' s plan: The Strategy's ultimate goal — changing how many Americans report their drug use over 10 years — relies on influencing information that is self-reported rather than information about actual behavior. That does not mean that the White House will not try to change behaviors. But, since the major measures of drug use are self-reported surveys, the Strategy employs a two-pronged approach.

The first prong is to affect attitudes. Self-reporting is widely used in social science, but it runs into problems when used to measure sensitive or illegal behavior. The responses to drug use surveys probably reveal as much about the attitudes about the activities in question as it does about personal use. As a resAlt, the White House is investing heavily in efforts that influence attitudes, such as the new nationwide ad campaign and the anti-legalization information packets.

The fallout from having a policy dependent on self-reported drug use is that the government would eventually begin to distrust what its citizens were saying. So, the second prong of the Strategy is a plan to increase drug testing dramatically. Already, both Clinton and McCaffrey have called for an increase in drug testing in the criminal justice system. They have praised drug courts, which require minor drug offenders to be tested often in order for them to avoid formal criminal charges, and they plan to test prisoners more routinely. Testing those in the criminal justice system, however, is not enough.

In the 1998 Strategy, ONDCP explains that current drug use must be reduced to three percent (half of 1996's 6.1 percent). This means that eight million fewer Americans should report past-month drug use 10 years from now. ONDCP calculates that 5.5 million of the targeted eight million users are employed, adding that these workers "can and will be reached through workforce-focused program interventions." According to the Strategy, this means that workplace drug testing must increase 12 percent by 2002, and 24 percent by 2007. The goal is "an America where all institutions and business organizations of all sizes and types implement drug-free workplaces."

On another front, Clinton has endorsed a "Youth, Drugs, and Driving Initiative," which would provide funds for drug testing of teenagers before they can get a driver's license. Since many Republicans also agree with making drug testing more widespread, these tests are poised to become a routine part of life for many more Americans.

CONCLUSION

There are many other problems with launching a 10-year plan. It should be no surprise that 10-year plans outlive presidential administrations. By the time the deadline rolls around in 2007, the Clinton plan would have to have survived two presidential elections. Different administrations, even Democratic administrations, will have different drug policy priorities and different campaign promises to keep.

McCaffrey acknowledged this point in a radio interview shortly after the Strategy was released.

"Clearly, we can't bind the next administration," McCaffrey said on National Public Radio. "But, just as Kennedy committed ourselves to a 10-year effort to put a man on the moon, we've argued to the men and women in Congress: 'Let's join together ... to confront this...." This point is inconsistent coming from McCaffrey, who believes the "drug war" metaphor should be replaced with one about fighting cancer because fighting a disease is a continuous challenge, whereas a war is a temporary one.

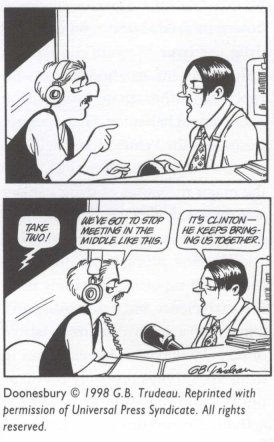

It should also be noted that, even with agreed-upon goals, the White House plan will not stop partisan disagreements over drug policy. Although Congress makes it clear that it is interested in seeing progress, Republicans are also interested in criticizing President Clinton. Republicans, like Democrats, are invested in publicly disagreeing with their opponents about drug policy. There is too much political capital among voters to do otherwise.

Another, deeper reason that Democrats and Republicans disagree with each other is to play down the fact that their policies are largely the same. Clinton made some cuts in Bush-era programs, but was savagely attacked and has since restored funding to these areas. As a result, both parties agree that spending more is better than spending less — no matter what is happening. As Americans reported less casual drug use in the 1980s, President Bush, with a Democratic Congress's blessing, instituted record high budgets, eventually spending over $40 billion in four years. With teenagers reported increased use, the Clinton White House also asked for and received record budgets. So far, Clinton has spent nearly $70 billion in five years.

The similarity of the Democratic and Republican drug policies is rooted in their adherence to the theory that prohibition is the best means of "controlling" drugs and drug users. To argue about that is to draw the public's attention to the horrible costs inflicted by a policy that subsidizes criminals, corruption, and violence. The result is that partisan disagreements are kept to more mundane issues, such as program spending, or symbolic issues, such as who is sending the "right" message.

Does the new Strategy change the course of drug policy? Not significantly. It will not change the escalating role government has played in the lives of its citizens. It will not open the question about the impact of prohibition on society. It is just as hemmed in by political correctness — "sending the 'right' message" — as the Reagan and Bush plans, so it cannot confidently propose progressive modifications, like syringe exchange or medical prescriptions of illegal drugs, let alone research on alternative policies.

Clinton's drug policy legacy may ultimately be a merging of Nancy Reagan's famed drug education mantra — "just say no" — and her husband's arms control saying — "trust, but verify." With congressional approval, widespread drug testing will become the ultimate checkmate against individually held attitudes about drugs. No longer will the government have to rely on ad campaigns to influence attitudes if it can search anyone who has something to lose, such as a job, a student loan, or a driver's license.

Although it is only $1 billion more than the current year, the new Clinton Strategy is championing a policy that promises to be far more invasive. Because it fails io focus on children and because it does not look into the dan-age caused by prohibition, the 1998 Strategy does the only thing it can do to make a difference: It makes drug policy a threat to all Americans' sealrity and constitutional heritage.

|