12. Cannabis Permissivism' and Social Response in Australia

| Books - Cannabis and Man |

Drug Abuse

12. Cannabis Permissivism' and Social Response in Australia

Simon Hasleton, Department of Psychology, University of Sydney, N.S.W., Australia.

It is worth reminding ourselves that cannabis use is a meaningful activity. By this, I mean only that its non-drug effects are more important than the strictly pharmacologic effect of the active elements. The evidence is that in most cases the dose taken in the naturalistic setting in 'Western' societies is such that the effects are evanescent, subjective, and highly sensitive to set and mood and expectation. (1) Indeed, there is every indication that the user not only requires an extensive coaching in recognising and responding to the effects of the drug, but that he is also capable of 'switching off' the intoxication should he need to do so. (2)

Nevertheless, this activity has generated an enormous response. It has been shown that in California alone, in one year, (1968) 51,000 persons were arrested for marihuana offences, at a cost to to the State of some 72 million dollars. (3) The drug has generated in the last few years, two major government sponsored reports, an embarrassing volume of other research, and not least, this series of conferences. This response could not possibly be explained in terms of the pharmacology of cannabis as a toxin, or in terms of its nuisance value as an elective intoxicant. The fact that the recommendations of the various Committees of investigation have been ignored, and that cannabis use continues to be prosecuted with the most draconian penalties and to be classified with the narcotics in many cases, indicates that the response to the use of this substance is not the rational outcome of its denotations.

This is not to imply that the response is irrational but rather that it has been generated by connotative aspects other than those which are investigated in ordinary scientific enquiry. In this paper, I wish to report two studies (4) which have explored some aspects of the 'meaning' of cannabis use, and the social response which this activity has generated. Both studies refer to Australia, a national community which derives some of its mores from Britain, some from Catholic Ireland, some from the United States West Coast, and many from its own recent experiences as the recipient of immigrants from most countries in Europe and many other countries beside.

These studies are unique, I think, in that they are based on large stratified random samples of the electorate. The use of such samples permits generalisation to the electorate as the medium of orderly social change, and reflects the belief that cannabis related activity is appropriately discussed in a political or macro-psychological arena.

The studies were designed to locate the cannabis issue within the context of other social issues, to examine the structure and complexity of the issues, the support they command, both absolutely and relative to each other, and the social and biographic correlates of that support. Within that framework, cannabis affiliations and the response they generate have been examined in more detail, in order to ascertain whether they comprise a special case, or whether they can be accomodated within the model.

METHOD

Australian National Polls Pty. Ltd. were commissioned to carry out two separate surveys on samples of the electorate in May and August 1973. A.N.O.P.'s sampling frame is based on a stratified random probability design, in which respondents are selected at random from the Commonwealth Electoral Roll, within electoral divisions which are selected on the basis of a series of social and political indicators. In each capital city, electoral divisions are ranked on a four level SES description and a three level political stability rating. Electorates are then selected in terms of each division's relative population proportion in the 4 X 3 combined levels of these two strata, and following further substratification at the subdivisional level, the random sampling of electors takes place in terms of enrolled electoral

populations. Sampling takes place in the whole Commonwealth, with the exception of the Northern Territory and the Australian Capital Territory. In each case the interviewer visited the respondent in his home, the statements being presented verbally and the responses being noted in the presence of the respondent. 1881 subjects were interviewed in one study and 1883 in the other.

In order to locate 'marihuana' with other social issues, a bracket of items was selected so as to be representative of those commonly discussed in the context of 'permissiveness' in Australia. The statements presented to the sample are set out below:

1. Do you agree or disagree that people over the age of 16 should be able to buy contraceptives?

2. ... that homosexuality between consenting adults should be legalised? ...

3. .., that censorship of books and films should be tightened up ...

4. ... that a woman should be free to have an abortion in the first three months of pregnancy without risking prosecution ...

5. ... that the community should frown on unmarried couples living together ...

6. ... that the smoking of marihuana should be legalised ...

7. ... that prostitution should be legalised ...

8. ... that divorce on request should be available to couples without children ...

9. ... that hotels should be closed on Sundays ...

10. that there should be more sex education in schools ...

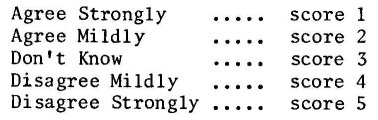

Responses were scored as follows, after inversion of items three, five and nine:

Acquiescence is recognised as a problem in studies of this sort. In this case, the three negatively cast items were combined with three positively cast items having a similar factorial composition, and a measure of acquiescence generated. This measure proved to have a very low correlation with the summed scores on the items (0.03) and with the score on the first principal component (0.07), and it was concluded that although acquiescence was present to a statistically significant degree, the findings were not substantially affected.

The first analysis of this material was designed to examine whether these items are related in such a manner as to allow discussion of 'permissiveness' as an entity. Product moment correlations were calculated between the items, and a principal component analysis performed for the total sample and a number of subgroups based on age and education.

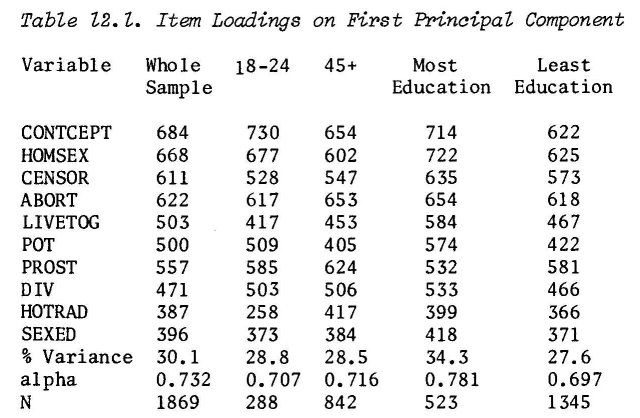

For the total sample, the proportion of the variance extracted by successive components was 30.14, 11.16, 9.45, 8.70, (etc). Factor scores calculated on the first principal component correlate 0.996 with the summed raw scores on the items: the generalized split-half reliability coefficient, (alpha) a measure of consistency, ranged from 0.781 for the tertiary educated to 0.697 for those with less than three years secondary education. Table 12.1 sets out the results of this analysis. (Item mnemonics will be self-explanatory.)

NOTE: Decimal points omitted from component loadings and cases with incomplete data suppressed.

It may be concluded that this set of items is related in such a way that it is meaningful to speak of 'permissiveness' as a unitary entity, and furthermore, that the tendency to conceptualise the items as having 'something in common' is higher among the tertiary educated than among those with less formal education. It should be noted that the marihuana issue is embedded in the general factor and is thus not considered as an issue separate from the general questions of personal liberty or licence which are raised by these items. Permissiveness can now be defined as that dimension which best accounts for the common variance in this set of items, in other words the first principal component, and scores on this component may be utilized as a measure of permissiveness.

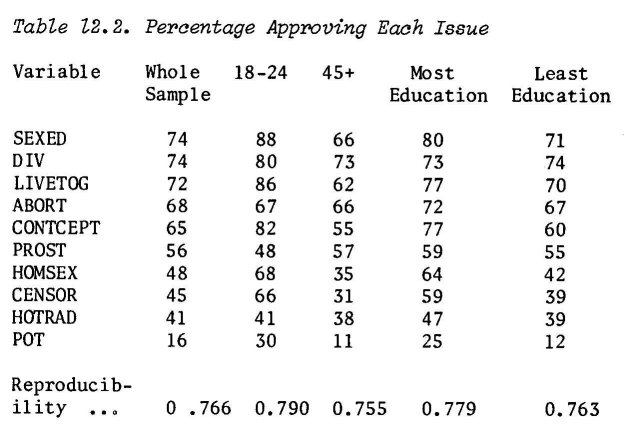

Subsequently, the relative difficulty and scalability of the items was tested entering a Guttmann analysis with a cutting point set above the 'don't know' score of 3. Table 12.2 sets out the results of this analysis.

This material raises a number of points for discussion. Among them are the generally high level of approval for permissive issues in Australia, and the way in which marihuana legalization is clearly of a higher order of item difficulty than the other items for all except the best educated and the 18 to 24 age group. Nevertheless, support for this item is fairly substantial. Utilising a recursive multiple regression technique, six variables were identified as predictors of permissiveness. These achieved a multiple R of 0.550 for the whole sample,

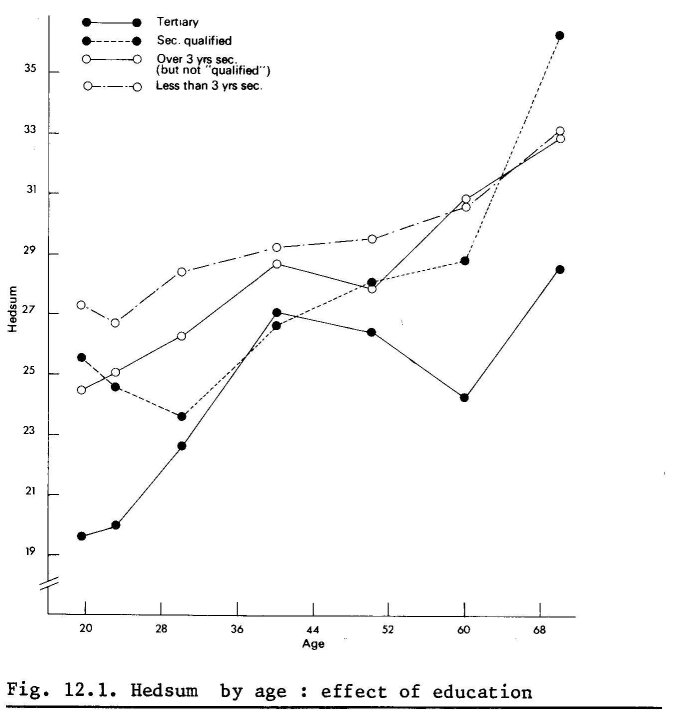

(F = 135.46, df = 6, 1862), and 0.583 for the 18 to 24 age group (F = 24.12, df = 6, 281). Four of these variables, church attendance, age, education, and Left v. Right voting intention accounted for 96 per cent of the predicted variance in the whole sample. To test for the presence of interaction effects, the summed raw item scores were now entered into a four way analysis of variance, classifying on the four predictors. The four main effects were significant beyond the 0.001 level, and three of the two-way interactions (age x church, education x church, and church x voting intent) were significant beyond the 0.01 level. The significance of the age by education interaction was obscured by the way the age groups were combined to maintain cell numbers, but emerges with some clarity in the graphical presentation. (5)

We do not know whether these trends are the result of cohort differences which have remained fairly stable

over the years, or whether changes occur within individuals over their life span. Material is available to the writer which will throw some light on this, but in the meanwhile it seems probable that both explanations are valid. Of direct relevance, it might be noted that there are two fairly clear patterns here. One is shared by the tertiary educated and those who have more than three years secondary education, but no secondary qualifications. The other is shared by those with secondary qualifications and those with less than three years secondary education.

The explanation of these trends is outside the scope of this paper, but the steep rise in anti-permissivism ('Wowserism' in Australia) in the most permissive group, has especial relevance for marihuana when it is recalled that this is the most extreme item in the 'scale'. In

all probability, this steep rise is a result of rapid exposure to the competitive world of business and the professions, and the demands of child rearing; one notes a downturn at age 40, when ambition starts to resolve and child rearing responsibilities to decrease. Studies currently in hand will enable a comparison between the present investigation and one conducted some years earlier in another form in Australia, and between the present study and a parallel investigation in the U.K., and these should enable a clarification of these questions and the underlying issue of the total rate of change in permissiveness, if indeed such change has occurred.

'Permissiveness' concerns a number of aspects of contemporary life. For example, patterns of drug use (including alcohol use) reflect societal norms which might well be discussed under this heading. It can be shown that opinions about marihuana held by the 18 to 24 age group are substantially predictable on the basis of opinions about homosexuality, contraception, censorship, abortion, prostitution and divorce. (R = 0.381, F = 7.77, df = 6,275). When the summed scores on the nine non-marihuana items are added to the biographic indicators marital status, sex, urban residence, political intent, and even in this restricted sample , age, R is increased to 0.454 (F = 11.91). The predictors are cited in the order of their importance. In the latter example the attitudinal predictor accounts for more than half of the predicted variance.

There is, however , a significant difference within the groups based on age and education in respect of the relationship between marihuana and general permissiveness. In the whole sample, the loading on the general factor is 0.500, indicating that 25 per cent of the variance in marihuana sentiments is explicable in these terms. In addition, there is a substantial loading (0.683) on a component specific to marihuana indicating that some 46 per cent of the variance is not explicable as 'permissiveness'.

This situation is not the case with those educated to the secondary qualified or tertiary level, where 32 per cent of the variance in marihuana sentiments is explicable as permissiveness and there is no component specific to marihuana.

On the other hand, the 'separateness' of marihuana sentiments is increased in the numerically larger less well educated group - who are also more 'anti-pot'. Here only 18 per cent of the variance is explicable as permissiveness.

Where groups are defined by age, the situation is more complex, but for those over 45, who account for some 45 per cent of the electorate (as represented in this sample), only 16 per cent of the variance is explicable as permissiveness, and 32 per cent as specific.

Thus one problem of marihuana control may be explicable as follows: in the least permissive, more anti-pot groups, the older and less well educated, marihuana is conceived as relatively separate from the 'permissiveness' issue. The pro-pot lobby finds few allies among the more permissive of this group (who are not very permissive anyway). The better educated and the younger are not only more permissive and more pro-pot but these two characteristics also share the same meaning.

This study has demonstrated that approval of marihuana legalization is a rather complex function of a more general factor, social permissiveness. The raw scores on the items which load on this factor have a platykurtic symetric distribution in the population, unimodal with a mean of 28.05 and a standard deviation of 8.48, indicating that the population is distributed around a mean of indecision on this dimension: the 'silent majority' simply does not exist, but will be referred to further below.

This indecision is reflected in a more detailed examination of marihuana affiliations and the social response they generate. Again in the context of this being the most difficult item on a permissiveness scale, a comparison of the various surveys commissioned on this topic since 1970 indicates a steady increase in the proportion of the population approving of legalization. In the general population from 7.4 to 17.3 per cent and in the under 30's, from 10.4 to 26.6 per cent. Currently, 50.7 per cent of the 18 to 20 age group state that they know one or more people who use marihuana and 33.2 per cent of the 18 to 20's believe that marihuana use should be legalized. For the total under 35 group 33.2 per cent know one or more users: pro-marihuana sentiments cannot be considered statistically deviant in the young population of Australia.

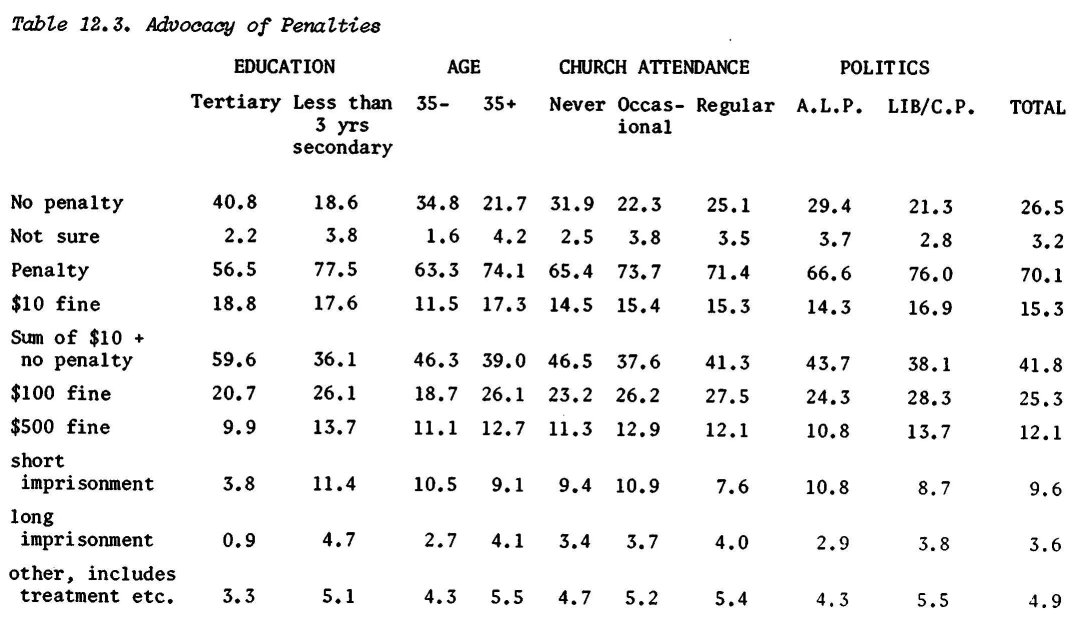

It therefore comes as no surprise that support for police action in this area is weak. Respondents were presented with a vignette in which they were asked about penalties in the case of an occasional user apprehended with a small amount of the drug in his possession. 70.1 per cent of the sample would impose a penalty, 26.5 per cent would not impose a penalty, and the balance are unsure. The percentages in favour of penalties are fairly consistent across the States, with Western Australia highest at 80.9 per cent, and New South Wales, the most populous state, lowest at 67.2 per cent. Support for penalties, and for more severe penalties, is clearly related to the discriminators which have been discussed previously: education, age, church attendance, and political affiliation. This is illustrated in Table 12.3.

Examining the congruence of current penalties being imposed in New South Wales courts for possession of a small quantity of marihuana, with current public opinion regarding penalties, responses of the New South Wales sample were compared with the penalties imposed on first offenders for Use or Possession in New South Wales courts of Petty Sessions in 1972. In that year 38.4 per cent were discharged without penalty, or were placed on probation, 11.4 per cent were fined less than $100, 22 per cent were fined between $100 and $199, 24.5 per cent were fined more than $200, and prison sentences were imposed in 2 per cent of the cases. This dichotomy between leniency and severity reflects the balance of public opinion in the State. 43.2 per cent of the N.S.W . sample approve of no penalty or

a nominal $10 fine, 23.4 per cent approve a $100 fine, 11.5 per cent approve a $500 find, 10.5 per cent a short period of imprisonment, and 3.3 per cent a long period of imprisonment. There are few 'victims' in marihuana offenses, and the police are reliant to a large extent on information from the public. However, only about 30 per cent of the sample state that they would inform the police or other authorities if they became aware that a group of young adults occasionally used the drug, as a against 81 per cent who state that they would take similar action if they became aware that 'a parent often severely beats his child'.

CONCLUSION

Pro-marihuana sentiments are closely related to permissiveness as a factor in social attitudes. In turn, permissiveness is a function of age, education, and disengagement from traditional and conservative attitudes, as indicated by Left voting intentions and 'not going to church'. If the drug is available, and the plant grows freely in Australia, then groups definable in these terms will use it, and approve its use, to the extent that such activity continues to be a facet of permissivism. Perhaps the best way of ensuring that the activity continues to

be so regarded is to persist with immoderate legislation and those authoritarian and moralistic statements which can be identified as coming from the opposite end of the dimension. Obversely, the best way of ensuring that such legislation and such statements persist, is to associate the drug with dirt, deviance, and rebellion.

But why, finally, do the traditionalists speak with such confidence of a 'silent majority' which manifestly does not exist? There is, I think, a simple reason. The overlap of the over 35's, the church going, the Right voting, and those educated to less than the secondary qualified standard, accounts for some 17 per cent of this sample. This group is the natural recruiting ground for the anti-permissive and is taken by the vociferous minority of the traditionalists to be representative of the general population.

The overlap of the under 35's, the better educated, the Left voting, and the non-church goers accounts for a much smaller proportion, some 4 per cent of this sample, so that the vociferous minority of the permissives can call on a smaller cheer squad. Alas, the left liberal tertiary educated are equally prone to speak as if their cheer squad represented the population.

The population, meanwhile, is undecided, and probably wishes that neither group would presume to speak so readily on its behalf. This, one suspects, is the most important characteristic of the silent majority.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

1. Jones, Reese T., (1971) Marihuana - induced 'high' influence of expectation, setting- and previous drug experience. Pharm. Rev. 23,4. 359-369. See also Howard Becker's classic 'Becoming a marihuana user', Am. J. Sociot. 59, 235-242 (1953).

2. Dr Smart's paper contains a reference to this aspect of cannabis use. The ability to 'come down' at will is part of cannabis folklore.

3. Kaplan, J. Marihuana, the new prohibition Meridian, N.Y. 1970.

4. One of these surveys has formed the basis for a paper in press with the British J. Addiction. Hasleton, S.L. and Simmonds, D.W. 'Is Australia going to pot: some trends relating to marihuana.'

5. A more detailed presentation of these findings is in preparation.

DISCUSSION

Dr Miles asked about the probable relationship of permissivism to the F scale by Adorno et al. which measures what might be called Fascism or Authoritarianism, and Mrs Mott about the Conservatism Scale, which has

many overlapping items with the F scale. Dr Leuw stated that his group has found a very high correlation between many of the sorts of item used by Mr Hasleton and the F scale.

Mr Hasleton replied that the reason for using the item chosen was because they were all issues under current discussion in Australia.

Ms Berntsen drew attention to the fact that according to this Australian data, the only issue on which the old were more permissive than the young was on the issue of prostitution!

Dr Rubin asked if Mr Hasleton's study, or any other study, had asked why respondents took the position that they did. Mr Hasleton replied that such a question would have to be pursued in a small intensively interviewed sample.

Following up this point, Dr Somekh asked how the data presented passed beyond the merely descriptive, and helped to explain the connotative aspects of cannabis that Mr Hasleton referred to at the beginning of his paper. Mr Hasleton replied that the data showed that cannabis was seen as an issue of permissiveness versus non-permissiveness; however, the data did not show why this was the case.

Dr Miles suggested that the general population had been given the impression for years that people who smoked pot were politically on the Left. Maybe this is an accurate impression to the extent that cannabis users express leftist attitudes when answering questionnaires. 'To be permissive is one thing, but to be in favour of people who are seen as having revolutionary thoughts is another matter altogether. This may be why your permissiveness scale gives such an apparently strong reading on marijuana.'

METHODOLOGY

Dr Smart asked about the sampling procedure: how were the elusive deviant younger males found. Mr Hasleton agreed that although attrition in this part of the sample might

be high, and that one might be ending up with a rather conservative selection of younger respondents. However, the intention was to get a sample of the population likely to vote (floaters don't vote) rather than a sample representative of the entire population.

Dr Edwards suggested 'One of the prime rules of factor analysis is that what comes out is determined largely by what goes in and by the initial choice of questions. The mere fact that you have asked about cannabis at the same time as you have asked about prostitution (as opposed to something like wallpaper), means that you have possibly invited a mental set in the respondent. You talk about attitudes to cannabis being embedded in the permissiveness factor. The word embedded is very appealing, and reifies the notion, but it would be good to be able to look at the raw data in a chi-squared form to see to what extent such a description seemed meaningful. I'm sure that attitudes to cannabis do correlate with these other attitudes, but I'm uncertain that the relationship is as large as your elegant statistics lead us to believe.'

Mr Hasleton replied that "The statement that what you get out of factor analysis is what you put into it is, of course, correct. Our task was to test the hypothesis, using component analysis, that a structure of correlations exist to the extent that we could talk about the existence

of permissiveness. We were able to support the hypothesis. The question of the effect on the respondent of putting forward these items together is unanswerable by this data, but is answered by studies which find that these permissivism items do come out as a coherent group from a larger set of items presented to respondents (see a study Eysenck and Wilson, in press B. J. Soc. and din. Psy.)'.

POST-CONFERENCE ADDENDUM TO MR HASLETON'S PAPER

Since this paper was presented the first results of the U.K. survey have come to hand. The sample was constructed along the same lines as those drawn for the Australian studies, and comprised 1968 respondents. The most important differences between the two communities concern the factorial complexity of permissiveness, and the differing contribution of pro-marihuana sentiments to permissiveness.

In the tralian samples it was clear that the first principal component was an acceptable measure of a permissiveness dimension. The minor cluster of items representing abortion, prostitution, and divorce lay oblique to the major dimension, and the item representing marihuana legalisation was moderately correlated with that dimension in the manner described.

In the U.K. sample, the factorial structure is more complex. Three components have eigenvalues greater than unity, accounting for 27.6 per cent, 11.4 per cent, and 10.6 per cent of the total variance respectively. When iterated for communality and rotated to the varimax criterion, three rather 'clean' orthogonal factors emerge. The first, labelled 'permissiveness ' has loadings in excess of 0.40 on contraception, censorship, prostitution, homosexuality, and 'living together'. The second has loadings on sex education and

(a new item) drug education, and a low (0.32) loading on contraception, and might be called 'moral education'. The third has a loading of 0.64 on abortion, 0.43 on divorce, and 0.25 on contraception. This is perhaps best thought of as a factor of 'Catholic morality' in which case the low loading on contraception is worthy of note. All the loadings discussed are positive.

In the Australian samples, the proportion in favour of cannabis legalisation was 17 per cent. In the U.K., the proportion is very much lower: only 9 per cent of the total sample advocating such a change. This indicates that there has hardly been any change in this respect since 1969. In January of that year, National Opinion Polls Ltd. reported that 8 per cent of the sample believed that the penalties for possessing 'pot' should be reduced, (4 per cent d.k.) and in April 1972 12 per cent believed that the 'smoking

of cannabis should be allowed' (5 per cent d.k.). Subsequent analysis may reveal a different trend among the young, but for the total adult population, the early indications are that procannabis sentiments are restricted to a small minority of the population.

This is entirely in accord with.the suggestions expressed in the paper: in the U.K. cannabis does not load on the dimension of social permissiveness, and hence has not been a part of whatever changes may have taken place in this respect.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|