Chapter 6 Enlargement 2005: cannabis in the new EU Member States

| Manuals - Cannabis Reader |

Drug Abuse

Keywords affordability – availability – cannabis use – EU enlargement – herbal cultivation – law enforcement – public debate – social representations – social responses – supply routes

Setting the context

This chapter examines cannabis use in the 10 Member States which joined the European Union in May 2004. It attempts to identify patterns in a cluster, and aims to increase our understanding of cultural, social and economic issues which are deeply embedded in cannabis use patterns and social responses.

More time will be needed to grasp the full impact of how drug use is affected by such a root-and-branch political shift as EU membership — if indeed any generalisations can be made in what remain, even after EU membership, very diverse countries. Will cannabis use patterns in EU Member States converge or continue to differ? To what extent does changing affordability, or the geographical proximity to supply routes, affect cannabis consumption? Will new EU members also experience the shift to herbal cannabis cultivation, as witnessed in a number of EU countries? Can country peculiarities, such as the high prevalence of cannabis in the Czech Republic, be easily explained? After EU membership, how does drug use interact with other social, economic and health indicators?

This chapter offers some thoughts, impressions and observations on early experiences. These experiences invite further validation and consideration as the drugs data for these countries mature. Moreover, since this article was written the European Union has further grown: two new Member States, Bulgaria and Romania, joined in January 2007. Drug use in two candidate countries, Turkey and Croatia, has also begun to be monitored directly by the EMCDDA. As the Centre is increasingly sought to comment on drug use among its new members and near-neighbours, this chapter emphasises the value of expert local insights: the voices behind the statistics.

Further reading

European Union enlargement

European Commission enlargement website

EMCDDA (2006), Country situation summaries, European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, Lisbon

EMCDDA (2006), Reitox national reports, European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, Lisbon www.emcdda.europa.eu/index.cfm?nnodeid=435

McKee, M., MacLehose, L., Nolte, E. (eds.) (2004), Health policy and European Union enlargement, European WHO Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Series, Open University Press, Maidenhead.

Scott, J. W. (ed.) (2006), EU enlargement, region building and shifting borders of inclusion and exclusion, Ashgate, Aldershot.

Stephanou, C. A. (2006), Adjusting to EU enlargement: recurring issues in a new setting, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham.

Drugs and the new Member States

Central and Eastern European Harm Reduction Network (CEEHRN) website www.ceehrn.org

EMCDDA (2005), Illicit drug use in the EU: legislative approaches (11 February), European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, Lisbon

Websites of Reitox national focal points www.emcdda.europa.eu/index.cfm?nnodeid=403

Enlargement 2005: cannabis in the new EU Member States

Jacek Moskalewicz, Airi-Alina Allaste, Zsolt Demetrovics, Danica Klempova and Janusz Sierostawski, with Ladislav Csemy, Vito Flaker, Neoklis Georgiades, Anna Girard, Vera Grebenc, Ernestas Jasaitis, Ines Kvatemik Jenko, Richard Muscat, Marcis Trapencieris, Sharon Vella and Alenka iagar

Introduction

The 2004 enlargement of the European Union (EU) covered 10 countries of very different size, population and culture, spreading from the Baltic to the Mediterranean. Considering existing commonalities and differences, three broad groups may be distinguished: the Baltic States (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania); the Central European countries (Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Slovenia and Slovakia) and the Mediterranean islands (Cyprus and Malta). The number of their inhabitants ranges from just over 400 000 in Malta to over 38 million in Poland. Altogether, close to 80 million people live in the new members of the EU, sometimes referred to as the EU-10.

Significant differences exist in economic development and wealth among the EU-10. Gross national product (GNP) per capita adjusted for purchasing power varies from well below EUR 8000 in the Baltic states to over EUR 15000 in Cyprus, Malta and Slovenia. The new EU Member States are also very different in terms of political history. For about a half of the last century the Baltic states were part of the Soviet Union, and Poland,

the Czech Republic and Slovakia, as well as Hungary, belonged to the bloc of socialist countries bound militarily and economically to the Soviet Union. Slovenia was part of socialist Yugoslavia, while Cyprus and Malta experienced market economies and more pluralistic political systems after rejecting the colonial power of the United Kingdom about 50 years ago. Eight out of 10 new EU members have been affected, then, by root-and-branch social change in the last 20 years.

Introduction of multi-party political systems and reinforcement of the market economy have resulted in more personal freedom and economic growth in recent years. On the other hand, a sense of everyday security has deteriorated. According to the participants of the project, security deteriorated the most, followed by housing security. Cannabis has been an illicit drug of choice for relatively large segments of young people in Western Europe. After the fall of the Iron Curtain cannabis use has rapidly increased in prevalence in Central and Eastern Europe as well, both in terms of physical presence and as a symbol of affiliation to the Western youth cultures.

This chapter is co-authored by individuals from 10 countries. In the first stage of its preparation, representatives of each country produced a detailed inventory of available cannabis data in standardised format. The inventories served as background material that was used extensively during a two-day workshop with the aim to write a first draft of the chapter. The participants, divided into three groups which focused respectively on epidemiology, social perception and social responses, outlined three sections of

the chapter which were then elaborated by three individuals: Airi-Alina Allaste (social perception), Zsolt Demetrovics (social response) and Danica Klempova (epidemiology). Finally, the chapter was combined and edited by Jacek Moskalewicz and Janusz Sierostawski. Support and encouragement was offered by Linda Montanan i and Sharon Reidner Sznitman.

Epidemiology

History of cannabis in the region

Origins and industrial use of cannabis in the new EU Member States

Cannabis sativa was thought to be brought to Southern Europe by Scythians in the 7th century BC. After that it gradually spread to other parts of Europe (Booth, 2004; Encyklopéclia Siovenska, 1979). During feudalism, it was grown in central Europe, including the present territories of the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Slovenia, Slovakia and possibly also other new EU Member States (e.g. Cyprus), usually in small-scale production by farmers, who processed it to make fabric, ropes and oils.

The appearance of cheaper materials led to the replacement of hemp and decline of its cultivation. After the year 1945 the small-scale production of hemp almost disappeared. The industrial cultivation of hemp was, however, still present in some countries in the 1980s. Main products made from it included fabrics for clothes, ropes, sheets, bags, cords for tyres, upholstering materials, oil used to make lacquers and varnishes, soap, materials for the food industry, animal foods, medications, materials for the construction industry, cellulose, etc. The contents of THC in the hemp grown for industrial purposes was low — about 1%. At the end of the 1980s, growing and cultivation of cannabis was entirely stopped or heavily reduced due to stricter controls imposed by international conventions.

History of use of cannabis for its psychoactive properties

In Cyprus, cannabis as a psychoactive substance had culturally determined roots: both from Turkish culture present on the island, where cannabis resin used to be smoked in water pipes, and via Cyprus's central location in historical Eastern Mediterranean cannabis trading routes (Egypt, Greece, Lebanon, Syria, Turkey). In Slovenia, the use of cannabis for its psychoactive and hallucinogenic attributes is also believed to have been known to its inhabitants for centuries.

In Malta documented evidence of cannabis dates back to the early 1980s. During this time herbal cannabis was grown locally, mainly during the summer months. Between 1985 and 1990 an increase in trade between other countries resulted in an increase in the importation of cannabis oil, which is quite rare today, and Lebanese and Moroccan cannabis resin. The latter remains the most common type of imported resin in Malta.

In the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia anecdotal evidence exists about cannabis use during the revolt of the 'hippie generation' from the late 1960s on, although prevalence was rather low. This can partly be explained due to low THC content in domestic cannabis and low availability and relatively high prices of cannabis sourced abroad. In Slovenia, with its warmer climate, cannabis use was supported from home growing during the 1980s. In that period, often referred to by the users as a golden age, cannabis supply was based on principles of reciprocity, barter and gifts, and not based on a criminal black market (Flaker, 2002).

In Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, cannabis for psychoactive purposes is anecdotally reported to have been brought by soldiers serving their compulsory military service in Central Asian republics in the 1970s and 1980s. Herbal cannabis known as 'anasha' was consumed and brought home to some extent, especially by young soldiers (Kardi, 1993: 54-61, 58-63).

However, the history of the use of cannabis for its psychoactive properties in the 10 new EU Member States is only documented anecdotally, and historical sources in most of the countries are scarce. With the exception of Cyprus, and perhaps Malta and

Slovenia, before the 1990s the psychoactive properties of cannabis went either generally unrecognised or its use was very rare.

Contemporary prevalence of cannabis use

European School Project on Alcohol and Drugs

The most consistent data source for country comparison of cannabis use among teenagers is probably the European School Project on Alcohol and Drugs (ESPAD, see Hibell, this monograph). This survey took place in all of the 10 new EU Member States in the years 1995, 1999 and 2003 (Hibell et al., 1997, 2000, 2004).

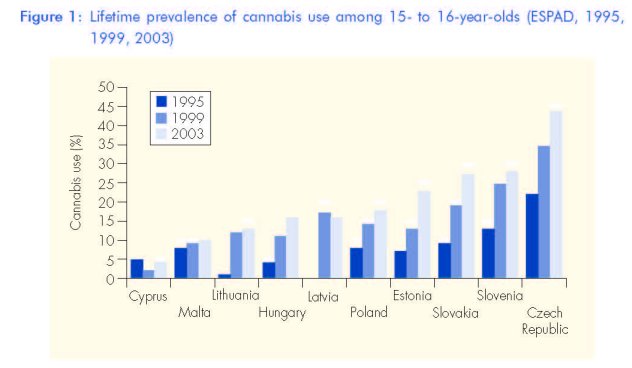

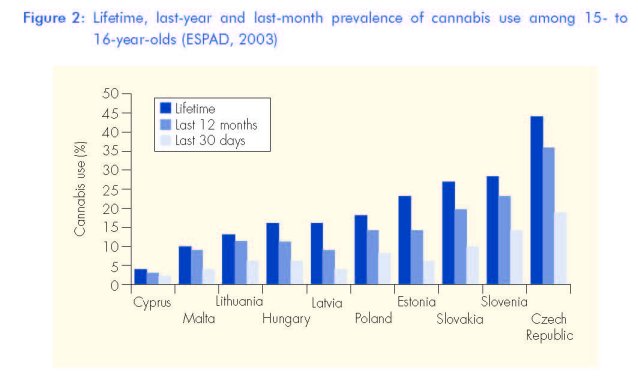

Figure 1 shows trends in lifetime prevalence of cannabis use among 15- to 16-yearolds, according to the ESPAD survey in the 10 new EU Member States, while Figure 2 presents differences between lifetime, last year and last month prevalence, as recorded in 2003 (Hibell et al., 2004).

The reported lifetime prevalence of cannabis use among 15- to 16-year-old ESPAD respondents increased in the years 1995-2003 in all new EU member countries except Cyprus, where it remained approximately stable at a relatively low level (2-5%). The increase in the years 1999-2003 was smaller in most countries than in 1995-1999. Among the 10 countries, a medium level of lifetime experience with cannabis can be found in the Baltic countries (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania) and in Hungary, Malta and Poland (10-18%). The highest lifetime cannabis use prevalence is reported in the Czech Republic (44%), Slovakia (27%) and Slovenia (28%).

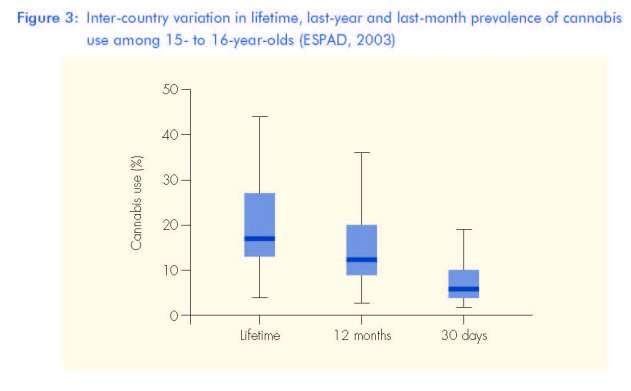

Last year and last month prevalence of cannabis use among 15- and 16-year-olds show similar time trends. Last year prevalence is lower than, yet mostly close to, lifetime prevalence in this age group. Last month prevalence, as an indicator of regular cannabis use, is much lower. In the three countries with the highest prevalence, regular use ranges from 18% in the Czech Republic through 14% in Slovenia to 10% in Slovakia. The range of the remaining seven countries is narrower and it varies from 2% in Cyprus to 8% in Poland. As a rule, prevalence of cannabis use during last month constitutes about 50% of the last year prevalence, while last year prevalence is 15-40% lower than lifetime cannabis experience. In effect, the wide gap among countries with regard to lifetime use tends to narrow with increasing frequency of use (Figure 3).

The three syringes above show inter-country ranges in lifetime, last year and last month prevalence of cannabis use. Each cylinder represents two quartiles of respondents spread either side of the median and, finally, a horizontal pusher indicates a median value of prevalence among all countries. The declining values of all three indicators confirm that the cultural gap in cannabis use tends to close with growing frequency of use.

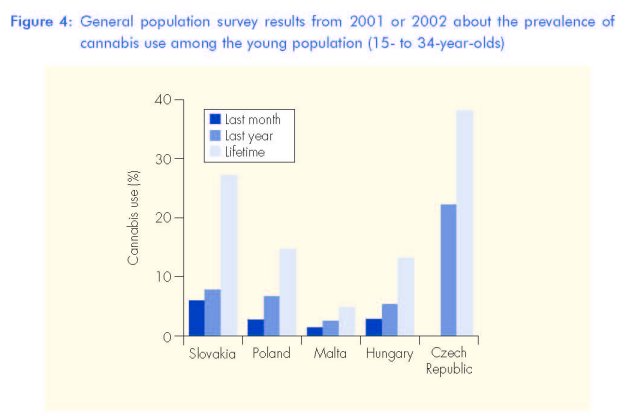

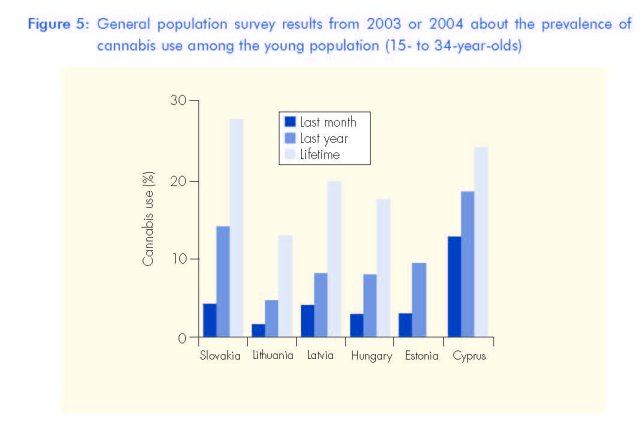

General population surveys

The general population surveys provide a picture of cannabis use among the young population (15-34), which is slightly different from the ESPAD results (see Figures 4 and 5). In Latvia, general population prevalence is similar to ESPAD survey results. In Lithuania, Slovakia and Hungary, the ESPAD results show similar values for lifetime prevalence, but indicate higher last year and last month prevalence. In the Czech Republic, Estonia, Malta and Poland, cannabis use among 15- to 16-year-olds surveyed by ESPAD is markedly higher than in the general population. Cyprus is the only country where general population data indicate higher prevalence than ESPAD data. There is a sharp contrast between figures for 15- to 16-year-olds — ranging from 1 to 5% — and those for young adults aged 15-34 — ranging from 13 to 25%. Data from Cyprus also show smaller gaps between lifetime experience and last year and last month use.

General population surveys across all 10 countries confirm that cannabis use is not only a matter of teenager behaviour, but is also prevalent among young adults up until their early 30s. Similarly to ESPAD, general population surveys show that while cannabis has been tried by a substantial proportion of young people, regular cannabis use is still only represented by small percentages of young adults.

Differentiation in cannabis use

Gender

Although in all countries cannabis use is higher among males than females, the size of the gap between the genders differs. Among 15- to 16-year-olds in 2003 there were five males to one female using cannabis in Cyprus, and two males to one female using cannabis in Latvia, Lithuania and Poland. The ratio ranged between 1:3 and 1:4 in Estonia, Hungary, Malta and Slovakia, and it was very small, at just below parity, in the Czech Republic (1:1) and Slovenia (1:1) (Hibell et al., 2004). It is worthwhile noting that a trend towards a more narrow gender gap was reported in most of the countries between 1 995 and 2003.

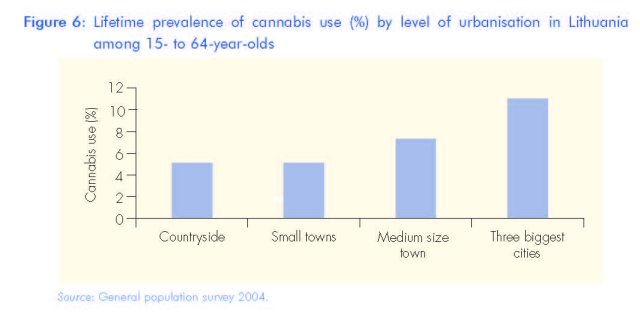

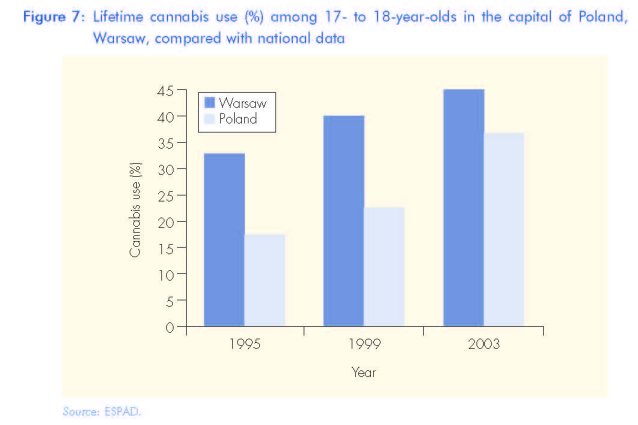

Urban versus rural areas

All of the countries which explored the difference between rural and urban areas found a higher prevalence of cannabis use in the larger cities, for example Estonia, Lithuania, Poland or Slovakia (see Figures 6 and 7). In some countries, this difference between urban and rural areas is levelling off (e.g. in Poland) while in others (e.g. Slovakia) it remains stable.

Other socio-economic factors

Data from the ESPAD survey in most countries revealed a clear association between cannabis use and truancy, sibling substance use and parents not knowing where the student spends Saturday night. A slightly weaker, yet still significant, association in most countries was living in a non-intact family structure. The association is unclear or nonexistent in the cases of parents' education and the economic situation of the family in which the respondent lives (Hibell et al., 2004).

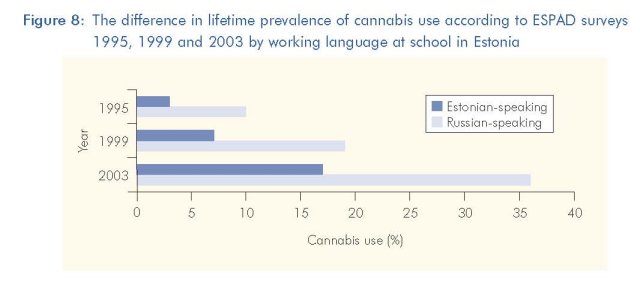

In Estonia, analysis of the available data also revealed higher cannabis use among the Russian-speaking part of the population. This discrepancy, which has slowly tended to narrow, can be attributed to a number of factors. First of all, Russian-speaking schools are mostly located in the cities where drug use is more widespread. Secondly, the Russian-speaking population lives in the north-western part of Estonia, which suffers from a higher level of social exclusion, including high unemployment and criminality, as well as alcohol and drug use (Allaste and Lagerspetz, 2005: 267-285) (Figure 8).

Patterns of cannabis use

Description of the patterns of use

In all new EU Member States, cannabis is found in all forms with various levels of THC concentrations: herbal cannabis and cannabis resin, both imported as well as grown indoors or outdoors. The general pattern of smoking cannabis herb or cannabis resin dominates, with herb dominating in some countries and resin in others. In those countries where the traditional consumption mode was the water pipe, this is fading and hardly exists among youngsters.

In most countries cannabis use has become more or less normalised among youths. This does not mean that all young people use cannabis, but that the drug is fairly available and the majority of youths are 'drug-wise' and tolerate cannabis use among others, even if they themselves do not use the substance (Parker et al., 1998). According to qualitative data, cannabis use does not increase the social status of the user, nor does it benefit from aggressive marketing. Cannabis has emerged simply as a part of the culture of young people, who want to have fun with their friends (Fatyga and Sierostawski, 1999).

Polydrug use

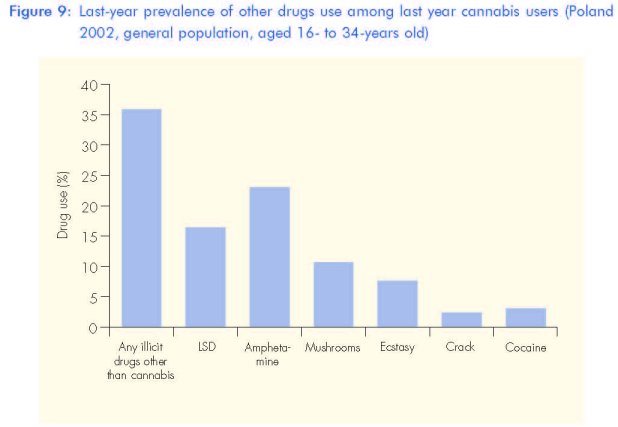

Users of cannabis usually have a higher probability to have experienced other drugs, in particular stimulants and hallucinogens (e.g. Zimmerman et al., 2005; Milani et al., 2005; Butler and Montgomery, 2004). This relationship also appears to hold true for the new EU Member States. According to secondary analysis of ESPAD data, last year prevalence of marijuana use in new EU members highly correlated (P< 0.05) with the prevalence of the use of ecstasy and any illicit drug other than marijuana and hashish (P=0.722 and 0.691 respectively).

According to Slovenian qualitative research (Kvaternik, 2004), young people in the age group 15-25 (pupils and students) usually engage in more risky behaviour than their older peers while using drugs. They consume more drugs (polydrug use) and larger quantities in any one occasion. Although being reasonably informed, it seems that in practice they do not seriously consider potential health risks.

Users of 'harder' drugs are more likely to have used cannabis too. Practically all ecstasy users use cannabis to recover from a night of exposure to ecstasy and noise (Demetrovics, 2001; Moskalewicz et al., 2004). On the other hand, the majority of cannabis consumers do not use other drugs, as documented by the Polish survey data. As can be seen from the graph, under one-third of cannabis users combine cannabis with other drugs, mostly with stimulants and hallucinogens, while 65% of them use only cannabis. It must be stressed that the vast majority of cannabis users never use opiates (Figure 9).

The role of social networks

According to ESPAD, in all of the 10 countries except Lithuania, the illicit drug first used, usually cannabis, is typically obtained from a friend, or shared in a group (ESPAD, 2003). Polish qualitative research has revealed that the pressure to use cannabis when peers are using is not perceived to be strong by young people. They argue that they are free not to use when they choose not to (Fatyga and Sierostawski, 1999).

Availability of the drug

Subjective availability

Availability of cannabis can be indirectly inferred from the data on perceived availability, police seizures data and also prices of the drug on the street as they indicate economic accessibility of drugs if related to incomes.

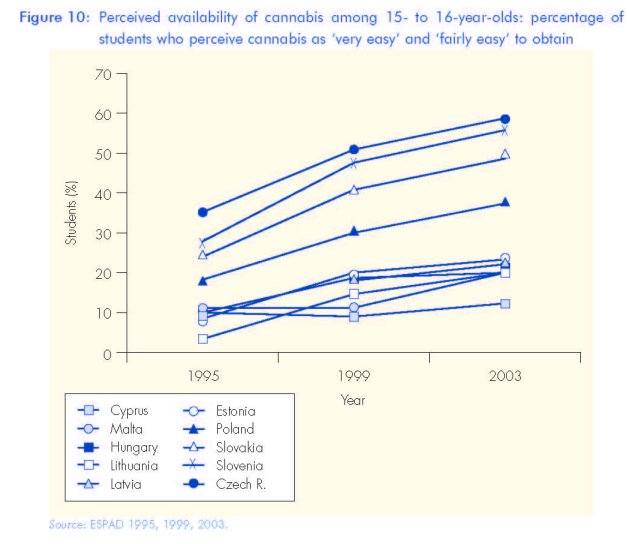

A few conclusions can be drawn from Figure 10. First, cannabis seems to be fairly easily available for a substantial proportion of students in all countries under review — from more than 10% in Cyprus to close to 60% in the Czech Republic. Second, perceived cannabis availability has increased in all countries, and no saturation effect has been recorded. In other words, countries that reported high availability already 10 years ago tend to see it growing as fast as remaining countries. Third, it is evident that large differences still exist among the new EU members. Four groups of countries emerge, the first being high availability countries, including the Czech Republic, Slovenia and Slovakia, where subjective availability is around 50% and over. These countries are followed by Poland, where the indicator approaches 40%. Then, remaining countries report availability of approximately 20%. Finally, Cyprus reports the lowest availability, where only 12% of students consider cannabis easily available.

Economic accessibility

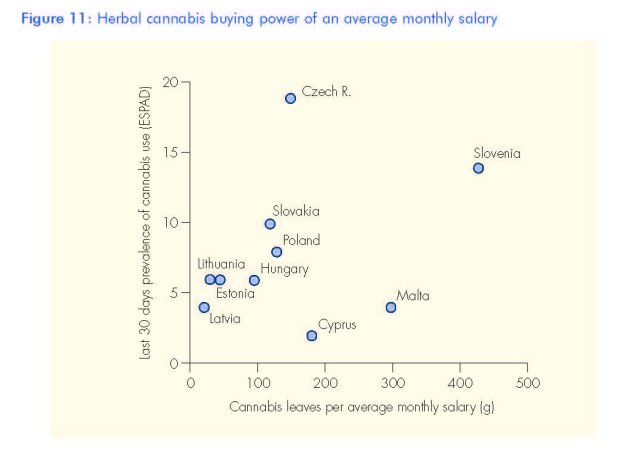

For decades, centrally planned economies in Eastern Europe were economically relatively self-contained. The economic systems included the non-convertibility of their currencies. In effect salaries, although adequate in terms of purchasing power, were extremely low when exchanged to any convertible currency, varying between USD 20 and USD 50 per month. On the one hand, smuggled cannabis was practically unaffordable for young people, and, on the other hand, Central and Eastern European markets were of little interest for illicit suppliers. The transition to a market economy brought with it the convertibility of national currencies and a rapid increase of nominal incomes calculated in hard currencies. More than a decade after this transition, prices per gram of cannabis in the EU-10 have become relatively stable and are close to prices in the EU-15, ranging from EUR 3.5 in Slovenia to EUR 17 in Latvia.

There are substantial variations in prices in relation to purchasing power, too. The average monthly income in the Baltic States equates to the value of 30-50g of cannabis, in the Central European countries to 100-150g. In Cyprus, Malta and Slovenia, where the currencies have been convertible for decades, an average monthly income could buy 200-400g of marijuana.

Figure 11 shows that herbal cannabis prevalence increases with average purchasing power. This is particularly the case for former socialist countries, where national currencies became suddenly convertible at the beginning of the 1990s, and where purchasing power for imported goods increased manifold almost overnight. The outliers of this linear relationship are countries with very high (Czech Republic) or very low (Cyprus and Malta) cannabis use. Cyprus and Malta represent relatively affluent societies with a longer history of a market economy, where cannabis has been relatively affordable for decades. The third outlier — the Czech Republic — has the highest prevalence of cannabis use worldwide. Its high position on the plot may partially be attributed to its relative wealth. However, all three outliers confirm that socio-cultural factors in drug consumption are more important than affordability alone.

Social representations of cannabis in new EU countries

General perception of the drug problem

Officially, the new EU countries do not make distinctions between cannabis and other drugs, and the general public supports such grouping of illicit drugs. In most countries, the media tends to sensationalise drug use (Paksi, 2000: 70-86). This means that overdose cases, seizures and other drug-related crimes are overexposed compared with other major social questions. Cannabis, if discussed at all, is primarily mentioned as a gateway drug, and the normative idea that smoking cannabis leads to use of harder drugs is expressed from time to time in most of the countries. As is common in many countries, problem drug users are often stigmatised. A common presentation of drug users that is propagated through the media is the image of drug addicts as dirty asocial human wrecks with frantic eyes. However, according to public opinion surveys from Poland and Estonia, people tend to perceive drug addicts as ill people rather than as criminals (Laidmde and Allaste, 2004: 118-143).

Perception of cannabis by the younger generation

Whereas the older generations tend to perceive all drugs as equally dangerous, younger generations tend to consider cannabis less harmful than other drugs in all the new EU countries. The generation gaps emerge with rapid social and cultural change and 'the young quickly acquire "new strategies of action" for coping with life in unsettled times' (Misztal, 2003: 85). Illicit drugs were introduced to the Baltic market only during the last decade, and to the Central European markets only a little earlier. This created a situation where the younger generations, who are experimenting with drugs, know more about the topic and are also much more tolerant than the older generations.

According to the ESPAD study, social condemnation of experimenting with cannabis is decreasing in Central Europe, and the most tolerant attitude towards this issue is displayed by school teenagers in the Czech Republic and Poland.

Although cannabis use has become ordinary, especially in the countries of Central Europe, it has also sometimes acquired a symbolic meaning of rebellion, at least in some youth cultures. Nevertheless, this rebellion is not a total negation of the society's value system, as was evident in the 1960s. Today, young people consider cannabis prohibition hypocritical within the context of the growing availability of alcohol. They either question the right of the state to impose the ban or demand that liberal economic policies applied to legal drugs should be extended to cannabis.

Images of cannabis in the arts and the media

Cannabis is not used extensively in the established visual arts, but the portrayal of cannabis with clearly positive connotations can often be seen in graffiti in most of the countries. Cannabis symbols are used in souvenirs, T-shirts, earrings, scarves, bracelets, cough drops, etc., and images of cannabis leaves can sometimes be found in book designs. However, these are niche products that can be bought from alternative shops or markets in most of the countries, and are found more commonly only in the Czech Republic.

Positive connotations of cannabis are much more often expressed in local popular and hip-hop music. In Poland, the vocalist Lora Szafran sings about the society which prohibits cannabis use but encourages youngsters to drink alcohol: 'The society is telling you that you better drink and smoke (tobacco) but grass is peace while alcohol — madness.' In the Czech Republic, the columnist of the magazine Reflex, Jiff Dole2al, has been a strong voice in cannabis advocacy (1).

Popular culture stresses the positive features of cannabis in contrast to other drugs: 'Weed unites people', 'Marihuana heals, other drugs — never use them'. Marijuana is strongly associated with rasta culture and hip-hop music, and the respective attitudes are openly expressed in the songs. Hip-hop has become a popular part of youth culture, and those who claim to belong to the sub-culture often call themselves: 'The Society of Hash and Scun', 'League of Blunters' or lbluntoholics'. All of these play on slang for cannabis. Cannabis use combined with alcohol seems to have become an integral part of their lifestyles, as well as its symbol (Demetrovics, 1998, 2001, 2005; Tossman et al., 2001).

Social response

Supply reduction

Legislation and policy

Drug legislation in all new EU members has evolved for several decades in an unexpected way. Twenty years ago drug legislation was restrictive and repressive in the Baltic States, as elsewhere in the Soviet Union. Restrictive laws prevailed in Cyprus and Malta, too. However, in Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland and Yugoslavia the penal sanctions were not that severe and possession of drugs was not penalised at all. In the 1990s when a number of 'old' EU countries tended to liberalise their drug policies, countries of Central Europe introduced more repressive legislation, which generally did not make any distinction between cannabis and other drugs.

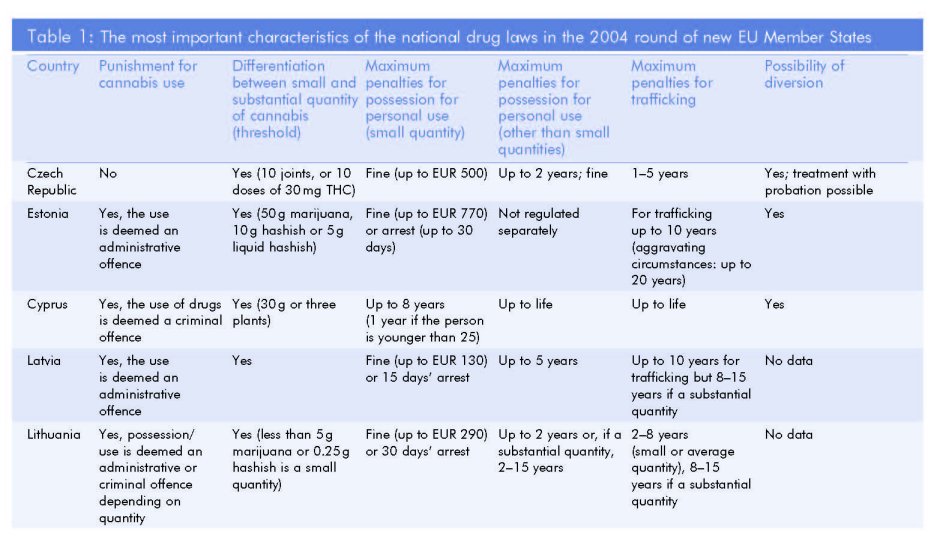

Currently, the new EU countries have stricter drug laws compared with the majority of pre-2004 Member States. Nevertheless, in terms of the most repressive legal control (prison sentences for drug use), only Cyprus among the 10 new EU Member States imposes prison sentences for drug use, vis-à-vis four existing Member States (Greece, France, Finland and Sweden). In addition to Cyprus, the Baltic countries deem drug use to be an administrative offence.

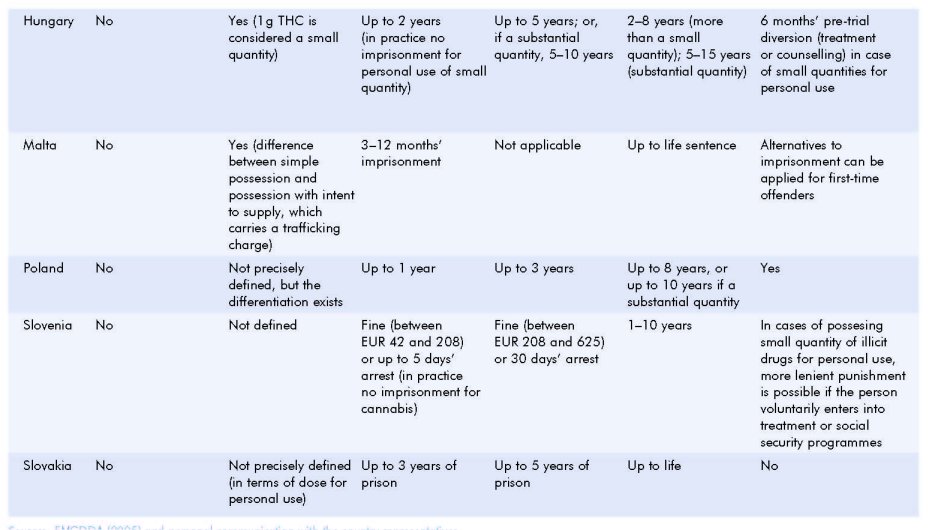

Possession of small amounts of drugs for personal use is criminalised in all of the new EU Member States, although differences exist between legislative penalties and actual sentencing practice at the judicial level. Nevertheless, in the Czech Republic, in the case of small quantities for personal use, and in the absence of aggravating circumstances, the law foresees 'administrative' sanctions only (EMCDDA, 2005). In the Baltic States (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania), possession of a small amount of any drug is considered a 'non-criminal offence'. The difference with regard to the Czech Republic is that in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania a 'non-criminal offence' may be punished by deprivation of liberty for up to 30, 15 and 45 days respectively. In Slovenia, possession for personal use is punished by a monetary fine or 5-30 days of arrest. In the remaining new EU Member States any kind of possession for personal use is considered a criminal offence, making sentences involving imprisonment possible (EMCDDA, 2005). However, possibilities to avoid imprisonment are available in some countries through diversion or referrals (entering treatment as an alternative of the legal process or imprisonment or suspension of a prison sentence). In other countries the application of the law seems to be more lenient than would be possible if the text of the law were taken literally. In Hungary, for example, two years of imprisonment is envisaged for possession of a small amount of cannabis for personal use only, but until the time of writing no-one has been sentenced to such a term of imprisonment. Differentiation between possession for personal use and trafficking exists in all 10 countries, while a differentiation between small and substantial quantities is defined in a number of ways. In some countries there is no exact definition, but the differentiation is based on whether the cannabis was for personal use or for dealing (Table 1).

Law enforcement

Among the new members, two groups of countries can be distinguished in terms of law enforcement (that is, the extent to which police and other law enforcement agencies implement a law). In the first group — Malta and Slovakia — any drug-related crime is subject to a high level of police activity, which means that the level of law enforcement is the same in the case of personal use as in the case of trafficking. In all other countries — with the exception of Estonia, for which data were not available — a more differentiated picture can be identified. In these countries use and possession of a small quantity of cannabis for personal use is enforced at a low or medium level, while the focus of the police and other agencies is on trafficking or possession of substantial quantities of drugs.

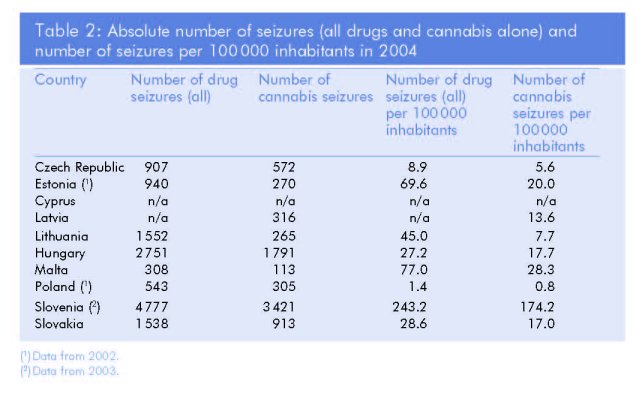

Other, more objective data show that the most seizures (both cannabis and other drugs) occurred in Slovenia (4 777 seizures for any drugs in 2003; 3 801 in 2004) followed by Hungary (2 952 in 2003; 2 751 in 2004), Slovakia (1 532 in 2003; 1 538 in 2004), Lithuania (1 029 in 2003; 1 552 in 2004), Estonia (1 060 in 2003) and the Czech Republic (979 in 2003; 907 in 2004). When drug seizures are calculated per 100 000 inhabitants, the highest rate of seizures is found in the smallest countries — Estonia, Malta and Slovenia — while the lowest is found in the Czech Republic and Poland. Only Hungary diverges from this rule, particularly with regard to cannabis, which has three times more seizures than the Czech Republic, yet a comparable number of inhabitants (Table 2).

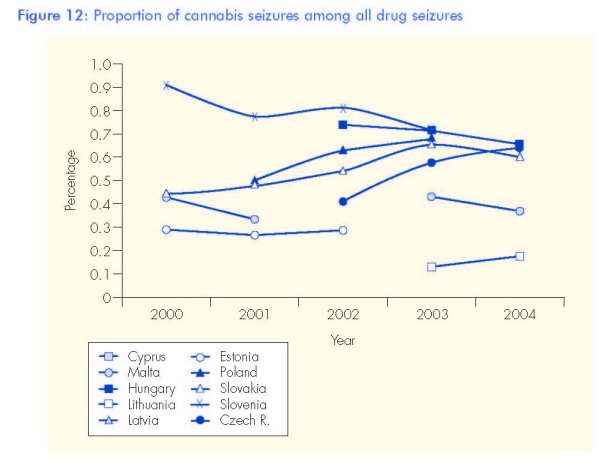

However, there are large differences in what percentage of these numbers are cannabis seizures. For example, in Slovenia in the past four years, 70-90% of all seizures were of cannabis. In the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia this proportion varied between 40 and 70%. Lower shares of cannabis seizures can be found in Lithuania (12-17%), Estonia (26-29%) and Malta (33-43%). Figure 12 suggests that the proportion of law enforcement efforts devoted to cannabis is converging in the 10 countries. In those with the highest 'cannabis oversight' (Hungary and Slovenia), the cannabis share in their seizures has declined while in the remaining countries this share has tended to rise (Figure 12).

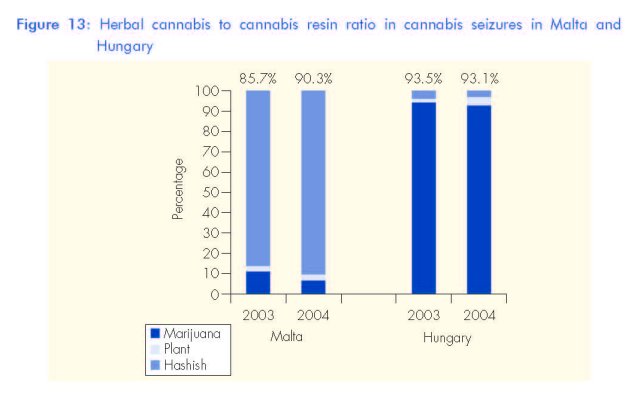

Data are available only from Hungary and Malta about the type of cannabis seizures, but these two countries are worth comparing as they represent substantially different profiles. In Malta the highest percentage of cannabis seizures is registered for cannabis resin (70% to well over 90%), while in Hungary herbal cannabis represents 93% of all cannabis seizures. This comparison may reflect either a great distinction in consumption patterns or a large difference in the focus of control (Figure 13).

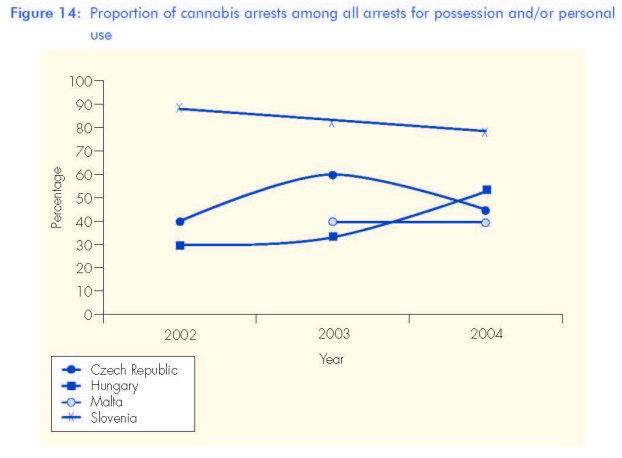

A substantial proportion of those who are arrested for petty drug offences — drug possession or use but not trafficking — is arrested because of cannabis. The highest percentage can be found in Slovenia, where four out of five arrests are related to cannabis. In the three other countries where data are available, this share varies from 30% to 60%.

Demand reduction

Prevention

Prevention campaigns in all 10 countries are dominated by school-based universal prevention programmes, and these naturally integrate cannabis-related issues. However, programmes do not specifically discuss this drug, and no specific emphasis is placed upon cannabis (Paksi and Demetrovics, 2002).

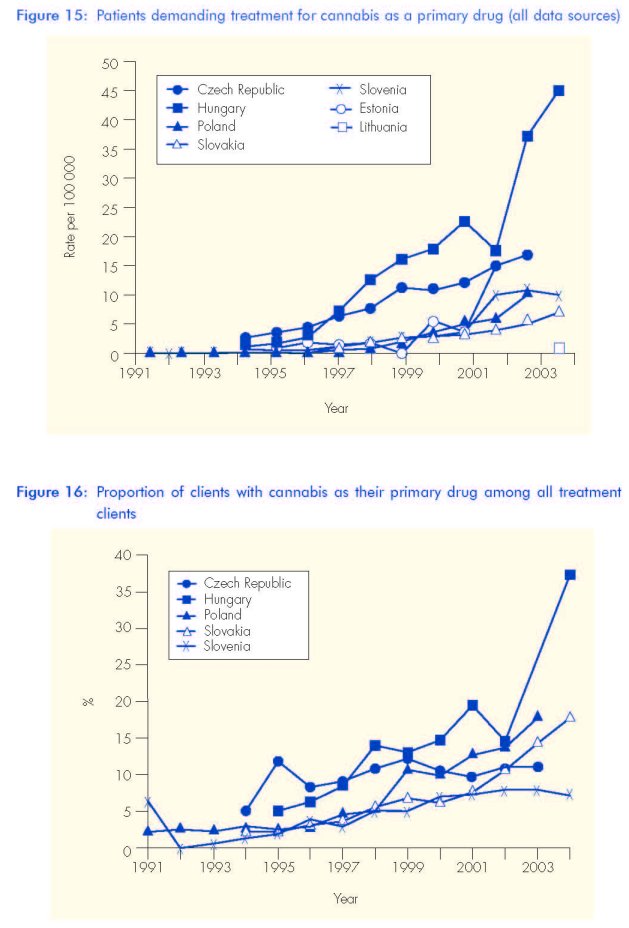

Treatment response

Among the 10 countries, Hungary has the highest prevalence of cannabis users in treatment (see Figures 15 and 16), estimated at 45 cannabis clients in treatment per 100 000 inhabitants (2004). Hungary is followed by Malta (32 per 100 000 in 2003), Estonia (15 per 100 000 in 2003) and the Czech Republic (14 per 100 000 in 2004). In all remaining countries there are 10 or fewer cannabis clients per 100000. As is also evident in the pre-2004 EU Member States (see Montanan i et al., this monograph), all of the new EU states have experienced a substantial increase in cannabis admissions to treatment in the past 10 years. This increase is, however, proportionately higher in Hungary than in the other countries. The reason behind this may be attributed to the proportionately high possibility of referrals (choosing treatment as an alternative to the legal process) rather than a greater need for treatment in Hungary. In 2004, for example, more than half of the clients entered treatment in the frame of referrals, and not on the basis of experiencing physical or mental problems which requires professional help.

Slovakia: outpatient treatment services

In relation to the graphs above, it must, however, be noted that the increase in demand for treatment is a complicated issue and not fully explained in the literature. Trends which indicate an increase in cannabis admissions may reflect: growing numbers of problem cannabis users who look for help with their medical problems; an increase in specialised services which may attract more clients; and more restrictive legislation and enforcement which forces cannabis users to seek an alternative to prosecution in the less repressive medical sector (see Simon, this monograph).

Public debate

Political debate

Officially, there is no distinction between soft and hard drugs in any of the new Member States. Nevertheless, there are some differences in perception of cannabis at the official level. In the Czech Republic, the National Drug Commission has initiated amendments in the legislation in order to distinguish between soft and hard drugs. In Hungary, the distinction between soft and hard drugs and decriminalisation of cannabis use are supported by the representatives of the Hungarian Liberal Party. In Poland, representatives of left-wing political parties also favour depenalisation of cannabis. In 2004, a member of the parliament from the then governing Democratic Left Alliance officially issued a statement on the legalisation of drugs, especially cannabis, which was widely quoted by the media. Two years ago, the agenda of a local left-wing party in Slovakia included decriminalisation of cannabis. By contrast, in the Baltic States and Malta, no officials have publicly expressed their support for the decriminalisation of cannabis.

The topic of legalisation of cannabis use has received much attention from the public in recent years. Much of this discussion has been driven by the liberalisation of drug policies and decriminalisation of cannabis in parts of Western Europe. In Estonia this Western liberalism is strongly opposed by the authorities. The Minister of Social Affairs stated publicly in a newspaper that use of cannabis is illegal and will remain illegal. In other countries, particularly in Slovenia, a co-author suggests that politicians may be waiting for EU directives or an external initiative in order to deal with this matter.

To summarise, opposing political forces tend to gain political leverage from the drugs question in general, and cannabis in particular. Their motives include generating support either among young voters who defend decriminalisation or legalisation, or among conservative elements of society who demand more repressive policies. This political context is counterproductive to a technical discussion on how to achieve a more rational consensus on cannabis policy.

Cannabis activist groups

In Central and Eastern Europe there are active groups advocating drug law reform in terms of depenalisation or decriminalisation of cannabis. In Hungary, one of the leading professional drug reform organisations is the Hungarian Civil Liberties Union (HCLU), which advocates the human rights of other vulnerable populations as well. The Hemp Seed Association (Kendermag Egyesület), a local users' group, actively speaks in favour of the legalisation of cannabis. Each year the Hemp Seed Association organises a demonstration as part of the Million Marijuana March (an annual, worldwide protest campaign for the legalisation of cannabis) in Budapest. It also initiated a civil disobedience movement in March 2005. Participants of this movement appeared at the National Police Headquarters, blaming themselves for violating drug laws in order to raise awareness of the criminalisation of drug users. In the Czech Republic, there are also rather professional organisations fighting for the rights of cannabis users, and there is also a 'Cannabis Ombudsman' whose mission is to help people who have problems with the law. In Poland, the Kanaba.info Association is a union of Polish drug users and other people alarmed by the present repressive drug policies. In 2003, they participated in ENCOD's 'Spread the Seeds' campaign and coordinated a public demonstration in Warsaw. In Slovakia, the non-governmental organisation (NGO) 'Free Choice' was established, as a response to the repressive legislative situation in February 2004. Its goal is to 'invoke discussion about cannabis and its legalisation and demythologise the plant that has been used for hundreds of years as food, a cure, for industry or pleasure'. In Slovenia, the Konoplja.org project campaigns for cannabis users to be given a political voice, together with the depenalisation of cannabis and the introduction of alternative sentences or admonitions. Every year, the Million Marijuana March is organised in Ljubljana and Maribor, where users can freely smoke cannabis (trafficking is forbidden) and point out that changes are necessary. In the Baltic States, Cyprus and Malta, activist groups exist, but are more covert and far less active and professional than in the above-mentioned countries. In the Baltic States, their main forum is the Internet, where they present articles and reports related to cannabis and its effects. There are also discussion forums and other information (legislation, pictures, smokers' stories, instructions on how to grow cannabis at home, extracts from legal acts, etc.).

Discussion

Eight out of the ten new EU Members States have undergone recent transformations from a centrally planned economy to a market economy, and from a single-party system to a pluralist political system. This shift has ushered in not only positive social developments but also a variety of problems which are measurable by 'objective' statistics and are often magnified in the public perception (Leifman, Edgren Henrichson, 1999). Drug problems, despite their high media exposure, are considered less important compared with other burning social issues such as unemployment, poverty and even alcoholism. Nevertheless, a rapid increase in drug use is recorded by relevant statistics (Moskalewicz and Swigtkiewicz, 2005).

Based on current data it is difficult to fully explore determinates of cannabis use in the new EU Member States and, therefore, some of the explanations offered in this chapter are hypothetical and need more research. The data do, however, point towards broad trends and crucial and intriguing issues, which should be monitored and researched more closely.

Cannabis is a widely used illicit drug in the 10 new EU Member States, particularly among teenagers and young adults. Its prevalence used to be somewhat lower than in the EU-15, but a rising tide of cannabis use in the years 1995-2004 has meant that the new EU Member States are reaching approximately the same prevalence rates as the rest of Europe (EMCDDA, 2004).

The sudden rise in cannabis use in all the new countries — except for Cyprus and Malta — has accompanied root-and-branch social change, which could have increased demand for psychoactive substances. Significant influences have been imported from the pre-2004 Member States, where cannabis use was more widespread and normalised than it used to be in the new Member States before the 1990s. Intensive transmission of Western European consumption patterns has affected drug use patterns in general, including cannabis. Young men and boys seem to be more open to the new patterns, particularly in the more religious societies (Cyprus, Lithuania, Malta, Poland) where the gender ratios in prevalence of cannabis use range from 2:1 to 4:1. In other, more secular cultures, such as the Czech Republic, this ratio is 1:1. The gender gap tends to narrow in practically all countries that have a tradition of female emancipation. As in other parts of the world, Westernisation first affects capital cities and larger urban centres. This is reflected by the dynamic geographic spread of cannabis in the countries, which has spread fast from large cities to smaller towns and then to the countryside.

This Westernisation hypothesis is supported by the fact that new EU countries with the highest cannabis prevalence — the Czech Republic, Slovenia and Slovakia, and to a lesser extent Hungary and Poland — are also those which are closest to pre-2004 Member States. The process of cultural homogenisation of Europe seems to be most advanced among younger generations, which are more willing to adopt new cultural patterns, including cannabis use. The image of cannabis has a very positive connotation in the context of rasta and hip-hop culture, both of which are international youth cultures. Cannabis is also popularised by movies, music and souvenirs. The force exerted by these influences seems to be higher in Central Europe, especially when comparing the Czech Republic with the Baltic States, Cyprus and Malta.

The low prevalence of cannabis use in Cyprus and Malta may also have its roots in culture. Unlike in the remaining continental countries, where cannabis has been integrated into teenage culture, particularly in large cities, cannabis for young Cypriots may be associated with traditional hashish waterpipes smoked by middle-aged and elderly men, and therefore have a much less attractive cultural appeal. In Malta, being a smaller country where social stigmas may be felt to a greater extent, open views about cannabis use may be more restricted.

Increasing cannabis consumption can be explained by its growing availability, which is confirmed by subjective opinions collected by the ESPAD study in all countries. The availability hypothesis has been backed up by data from international and national control agencies that focus on the supply side of the drug market. Nevertheless, our study suggests that the availability increase is a phenomenon present in all countries, including those where consumption has tended to level off, such as Cyprus, Malta and Slovenia. Moreover, it is difficult to explain large gender gaps in cannabis consumption recorded in a number of countries, despite its similar availability for boys and girls (see Hibell and Andersson, this monograph).

Cannabis prevalence cannot be explained by its affordability. There is no linear relationship between the economic situation of the country and its level of cannabis use. However, experiences in the new EU members suggest that the income-price elasticity of cannabis demand is much higher in those countries whose currencies recently became convertible and where incomes expressed in terms of convertible currencies tended to grow fast. In more stable economies, cannabis price elasticity is much lower.

Public discussion tends to demonise drugs, to place cannabis on a par with other illicit drugs, and generally to portray drug use as something dangerous. Illicit drug use in society is also generally stereotyped (Young, 1971: 182), and despite idiosyncrasies among the 10 countries, common features include the high social visibility of the drug problem and the negative image of drug addicts in general. Since the Eastern European countries undergoing transition still suffer from many unsolved social problems, drugs have been attributed the role of the 'good enemy' (Christie and Bruun, 1986); that is, drugs are seen as a straightforward political target, rather than attempts to resolve urgent matters such as the problems of disadvantaged groups, inequality in the employment market and undeveloped regional policy. However, especially regarding cannabis, it is possible to make distinctions between regions. In the Central European countries (Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Slovenia and Slovakia), cannabis has a higher social visibility than in the other countries, where the social perception of drug use is focused mainly on problem drug use. Nonetheless, since illicit drug use is a relatively new phenomenon in all of these countries, the older generations tend to have naive and homogenous views of drugs and drug users. Perhaps reflecting such concerns, the majority of new EU countries have recently introduced legislation that is more restrictive than under previous regimes.

Rapid political change in 8 out of the 10 new EU member countries and increasing integration with the EU has had a serious impact on drug policy. All these countries have become more open and more vulnerable to external pressures, particularly from the most powerful allies, such as the USA, which has attempted to exert its influence through relevant UN agencies and by targeting professionals as well as policymakers and politicians. Nordic countries, too, have tended to export their restrictive drug policies, especially across the Baltic Sea. On the other hand, pre-2004 EU members must also have felt the impact of enlargement in this area. Existing European divisions in drug policy may be reinforced by the new Member States, which are more likely to join coalitions of more restrictive countries.

The social response to cannabis is overwhelmingly dominated by individually oriented approaches, that is, law enforcement and treatment. From incomplete data it can be estimated that the number of cannabis users dealt with by law enforcement agencies is much higher than those in medical treatment. This results from increasingly repressive legislation which applies penalties even for possession of small amounts for personal use, which in fact implies penalisation of use. In some countries presence of cannabis in body fluids may legally be interpreted as possession. Such legislation implies that referrals to medical treatment, where present, are used as much as a social control as a psychosocial care method. In most countries cannabis-specific treatment is not widely available, and cannabis dependence is accepted as a phenomenon, which is not considered as requiring specific treatment centres and methods. Treatment of cannabis clients is integrated in general drug treatment settings which focus on opiate-dependent individuals. Thus, the growing share of cannabis users in medical treatment probably reflects referrals from the criminal justice system rather than impressive advances in treatment methods.

(1) Seth Fiegerman, Jir-i Doleial: 'Still looking for change', The Prague Post, 18 April 2007.

Bibliography

Allaste, A. A., Lagerspetz, M. (2005), 'Drugs and double-think in marginalised community', Critical Criminology 13: 267-285.

Booth, M. (2004), Cannabis: a history, St. Martin's Press, New York.

Butler, G. K. Montgomery, A. M. (2004), 'Impulsivity, risk taking and recreational ecstasy (MDMA) use', Drug Alcohol Dependence 76: 55-62.

Christie, N., Bruun, K. (1986), Hyva vihollinen. Huumausainepolitiikka Pohiolasso (Good enemy: Drug policy in Nordic Countries), Weilin and Gôôs, Espoo.

Demetrovics, Zs. (1998), 'Drugs and disco in Budapest: smoking, alcohol consumption and drug-using behaviour among youths in the clubbing subculture' (in English), Regional Resource Centre, Budapest.

Demetrovics, Zs. (2001), 'Droghaszneilat Magyarorszeig tâncos szôrakoz6helyein' (Drug use in Hungarian clubbing subculture), L'Harmattan Kiadô, Budapest.

Demetrovics, Zs. (2005), 'The characteristics of psychostimulant use in the Hungarian party scene', Abstracts of The Inaugural European Association of Addiction Therapy Conference Budapest, 6-8 July 20051 13.

EMCDDA (2004), Annual report: the state of the drugs situation in Europe, European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, Lisbon.

EMCDDA (2005), Annual report 2005, European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, Lisbon.

EMCDDA (2006), 'Web page: 'Possession of cannabis for personal use', European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, Lisbon

Encyklopéclia Slovenska [Encyclopedia of Slovakia], part III (1979), VEDA, SAV, Bratislava, 156. Fatyga, B. and Sierostawski, J. (1999), `Uczniowie i nauczyciele o stylach iycia i narkotykach', Raport

B. and Sierostawski, J. (1999), `Uczniowie i nauczyciele o stylach iycia i narkotykach', Raport

z badan jakoiciowych, Instytut Spraw Publicznych, Warsaw.

Flaker, V. (2002), 'Heroin use in Slovenia: social consequence or social vehicle', European Addiction Research 8: 170-176.

Hibell, B., Andersson, B. (2008), 'Patterns of cannabis use among students in Europe', this monograph.

Hibell, B., Andersson, B., Bjarnasson, T., Kokkevi, A., Morgan, M., Narusk, A. (1997), The 1995 ESPAD report: alcohol and other drug use among students in 26 European countries, The European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs, CAN, Stockholm.

Hibell, B., Andersson, B., Ahlstrôm, S., Balakireva, O., Bjarnasson, T., Kokkevi, A., Morgan, M. (2000), The 1999 ESPAD report: alcohol and other drug use among students in 30 European countries, The European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs, CAN, Stockholm.

Hibell, B., Andersson, B., Bjarnasson T., Ahlstrôm S., Balakireva O., Kokkevi A., Morgan M. (2004), The 2003 ESPAD report: alcohol and other drug use among students in 35 European countries, The European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs, CAN, Stockholm.

Kardi, V. (1993), 'Marihuaana ja hashishi tarvitajatest Eestis' [About marijuana and hashish users in Estonia], Yikerkaar 8 (5): 54-61 and 8 (6): 58-63.

Kvaternik, J. I. (2004), 'Drugs as an element of political relations: human rights on the example of the subculture of drug users', University of Ljubljana, Faculty for Social Studies, Ljubljana.

Laidmae, I., Allaste, A. A. (2004), 'Tervis' (Health), in Hansson, L. (ed.) Valikud ja vôimalused: argielu Eestis aastatel 1993-2003 [Choices and opportunities in everyday life in Estonia 1993-2003], Pedagooglise Ülikooli Kirjastus, Tallinn, 118-143.

Leif man, H., Edgren Henrichson, N. (1999), 'Statistics on alcohol, drugs and crime in the Baltic Sea region: NAD Change, Helsinki', European Addiction Research 8: 170-176.

Milani, R. M., Parrott, A. C., Schifano, F., Turner, J. J. (2005), 'Pattern of cannabis use in ecstasy polydrug users: moderate cannabis use may compensate for self-rated aggression and somatic symptoms', Human Psychopharmacology 20: 246-263.

Misztal, B. (2003)1 Theories of Social Remembering, Open University Press, Philadelphia.

Moskalewicz, J., Swiqtkiewicz, G. (2005), 'Naduiywanie substancji psychoaktywnych na tie innych problem6w spotecznych w Polsce (Drug abuse in Poland against other social problems)', in Piqtkowski, W., Brodniak, W. A. (eds) (2005) Zdrowie i choroba. Perspektywa sociologiczna (Heath and illness: a sociological perspective), Wyisza Szkota Spoteczno-Gospodarcza, Tyczyn, 203-216.

Moskalewicz, J., Swiqtkiewicz, G., Dqbrowska, K. (2004)1 'Ecstasy use in Warsaw: do cultural norms prevent harm?', in Decorte, T., Korf, D. J. (eds), European studies on drugs and drug policy, VUB Press, Brussels, 179-193.

MravCik, V., KorCigov61 B., LejCkov6, P., Miovsk6, L., t'krdlantov6, E., Petrog, O., Radimec4, J., Sklen6i=, V., Gajdogikov6, H., Vopravil, J. (2004), Annual Report of the Czech Republic — drug situation 2003, Office of the Government of the Czech Republic, Prague.

MravCik, V., KorCigov6, B., Lejacov6, P., Miovsk6, L., t' krdlantov6, E., Petra, O., Sklen61=, V., Vopravil, J. (2005), Annual report of the Czech Republic — 2004 drug situation, Office of the Government of the Czech Republic, Prague.

Paksi, B. (2000), 'A szintetikus szerek képe a magyarorsz6gi sajt6ban (Presentation of drugs in the Hungarian medla)1, in Demetrovics, Zs. (ed.), Diszkenlrogok, drogfogyaszt6k, szubkult6r6k (The World of Synthetic Drugs. Disco drugs, drug users, subculture), Animula, Budapest.

Paksi, B. and Demetrovics, Zs. (2002), A drogprevenci6s gyakorlat megismerése. (Evaluation of school prevention programmes), L'Harmattan, Budapest.

Parker, H., Aldridge, J., Measham, F. (1998), Illegal leisure: the normalisation of adolescent recreational drug use, Routledge, London.

Tossman, P., BoIdt, S., Tensil, M-D. (2001), 'The use of drugs within the techno party scene in European metropolitan cities', European Addiction Research 7: 2-23.

Young, Y. (1971), The drugtakers: the social meaning of drug use, Paladin, London.

Zimmermann, P., Wittchen, H. U., Waszak, F., Nocon, A., Hofler, M., Lieb, R. (2005), 'Pathways into

ecstasy use: the role of prior cannabis use and ecstasy availability', Drug Alcohol Dependence

79: 331-341.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|