Chapter 15 Multinational export-import ventures: Moroccan hashish into Europe through Spain

| Manuals - Cannabis Reader |

Drug Abuse

Keywords: cannabis — cannabis resin — crime networks — criminology — Morocco — socio-economic analysis — trafficking

Setting the context

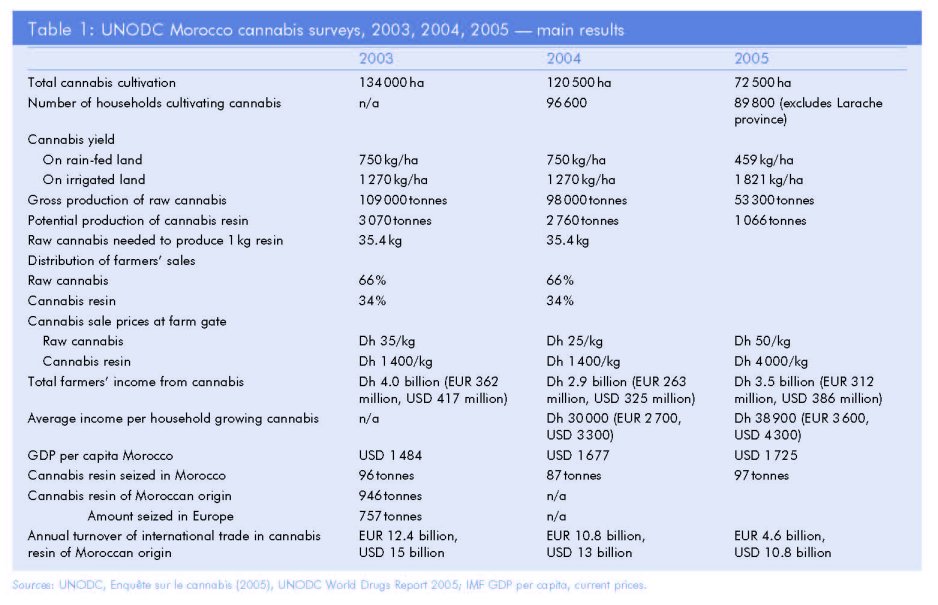

In recent decades, Morocco has emerged as the world's largest producer and exporter of cannabis resin, or hashish. The Moroccan cannabis resin market is substantial: the country supplies over 70% of the cannabis resin consumed in Europe, and half of global production (EMCDDA, 2006). Within Morocco itself, hashish is one of the key agricultural products of the provinces containing the Rif mountain range in northern Morocco, and an estimated 760 000 peasant farmers (2.5% of the population) obtain their livelihoods from hashish. By 2003, Morocco's cannabis resin production had reached 3 070 tonnes, with a retail market value estimated at over EUR 12 billion by the UNODC. Since then, cultivation has decreased substantially, due both to crop eradication efforts, political pressure placed on the Moroccan government and the damage wrought by a major drought in 2005. The most recent UN figures put production at around 1 070 tonnes, resulting in a retail market estimate of EUR 4.6 billion.

The full picture of hashish trafficking is more complex. It is estimated that only about a tenth of the retail earnings are likely to end up in the pockets of Moroccan farmers, wholesalers and traffickers. The majority of profits are made lower down the supply

chain once the resin has entered the EU. Most Moroccan hashish is exported through the Iberian peninsula, particularly Spain, a country that is today the crucial transit zone for Moroccan hashish sold in the European market. From Spain, cannabis resin is bounced through a complex network that unites producers, traffickers, dealers and consumers.

This chapter examines the export—import system of cannabis resin between Morocco and the EU through Spain. It combines a review of the literature on the Moroccan production of hashish and a preliminary analysis of over 2 000 press reports using an event history analysis approach (Franzosi, 1995; Olzak, 1992). The result is data on 1 370 groups of importers and dealers apprehended during a 27-year period, and a first sketch of the structure of the multinational smuggling industry. The result is a typology of networks and groups who deal with hashish at different levels of a distribution pyramid, profiled according to the size of 'project' they manage. The chapter thus clarifies the importance of networks and hierarchies in illegal enterprises, the type of complex and impermanent structure that has received considerable attention in EU criminology literature (see Dorn et al., 2005).

A number of enforcement questions arise from this chapter. Given the strong decrease in Moroccan cannabis resin production, is supply moving elsewhere? A number of countries in northern Europe are reporting increasing use and domestic cultivation of cannabis herb (see Carpentier, this monograph), with an indirect effect on the potency of cannabis consumed (see King, this monograph). Recent press reports also suggest that Sub-Saharan Africa is stepping into a gap in the market: seizures of resin are increasing along the Saharan route via the North African coast, and countries such as Algeria, Libya, Niger and Mali have reported overall increases in seizures. However, given the fluctuation that characterises such seizure statistics, it is difficult to draw clear conclusions. Another question is whether Moroccan cannabis resin trafficking networks are diversifying into cocaine trafficking. This is a concern expressed by the Spanish and French authorities, together with Europol with some concern about cocaine seizures on the Ceidiz coast, a traditional hashish route. Reported seizures of cocaine in Morocco have fluctuated greatly since 2000, peaking at 15.8 tonnes in 2002, yet with a wide range starting at 0.9 tonnes in 2000 to just over 4 tonnes in 2004 (UNODC, 2006).

Further reading

Dorn, N., Levi, M., King, L. (2005), Literature review on upper level drug trafficking, UK Home Office Online Report 22/05, London.

Europol (2005), European Union situation report on drug production and drug trafficking 2003-2004, Europol, The Hague.

UNODC (2007), 'Invisible empire or invisible hand? Organized crime and transnational drug trafficking', Chapter 2 in World Drugs Report 2007, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime Control, Vienna.

UNODC and Kingdom of Morocco (2007), Enquête sur le cannabis 2005, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Vienna.

Multinational export-import ventures: Moroccan hashish into Europe through Spain (1)

Juan Francisco GameIla and Maria Luisa Jiménez Rodrigo

Introduction

The production of cannabis is a global phenomenon; 134 countries have been identified as source countries of this substance (UNODC, 2007). Two regions, however, concentrate the largest markets for cannabis products, and the largest accumulation of revenues: North America, where two-thirds of all cannabis products are sold, mainly in the form of marijuana, and Europe, the largest importer and consumer of resin or hashish (for more detail on the world cannabis market, see Legget and Pietschmann, this monograph).

While the production of herbal cannabis is widely dispersed around the planet, including a growing number of European home-growers, the production of resin is centred in a few countries such as Morocco, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Lebanon and Nepal. Among them, Morocco has become the world's largest producer and exporter, supplying over 70% of resin consumed in Europe (EMCDDA, 2007). Although statistics vary widely, in recent years Morocco's hashish production has declined from 3 070 tonnes in 2003 to 1 070 tonnes in 2005 (UNODC, 2007). Average retail prices for cannabis resin is reported in Europe at between EUR 2.30 and EUR 11.40 per gram, while cannabis resin seizures for 2003 in Spain and Portugal were reported at 809 tonnes, or just over a quarter of Moroccan production (EMCDDA, 2006). The UNODC's estimate of the annual international market for Moroccan cannabis resin has seen a decline from EUR 10.8 billion in 2004 to EUR 4.6 billion in 2005.

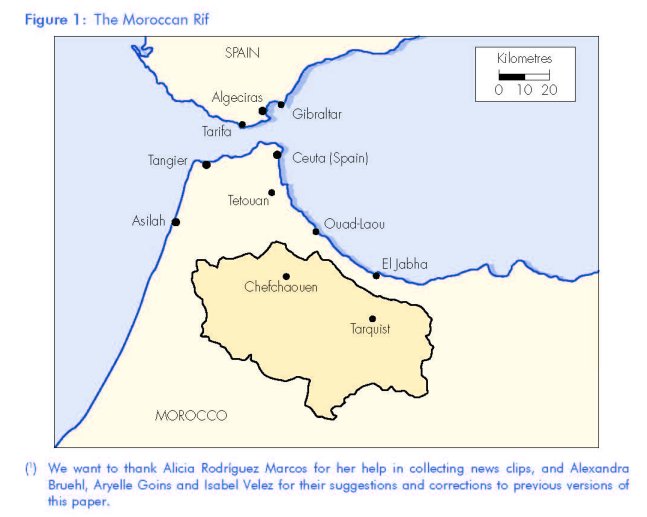

Most Morocco-produced hashish is exported through Spain, a country that is today the crucial transit zone for Moroccan hashish sold on the European market (Figure 1). In 2003, out of the 757 tonnes of Moroccan resin seized in the EU, 727 tonnes (over 90%) were seized in Spanish territory or jurisdictional waters (UNODC, 2005). This binational industry has exploded in the last three decades from a traditional base of rural growers in the Ketama region, whose products were distributed from the late 1960s by hippie entrepreneurs. In the last decade, smuggling networks have begun to move faster and further, and to establish international connections with traffickers of other drugs, for instance with large cocaine exporters from South America, who are increasingly using the routes opened by the distribution of Moroccan hashish.

The 14 km of the Strait of Gibraltar, and the frontier around the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla, make up one of the deepest socio-economic and cultural divides on the planet (2). Disparities in wealth, income, demographic structure, educational and labour opportunities are huge and stimulate a licit and illicit movement of persons that in many ways parallels the movements of drugs, money and manufactured products. This is a crucial frontier for the EU and its policies concerning development, immigration and drug control.

This chapter examines the export—import system of cannabis resin between Morocco and the EU through Spain. First, we will review what is known about the extent, location and organisation of cultivation and manufacture in northern Morocco. We will then explore the structure of the import industry using Spanish data. We will consider the type of organisations and networks that participate in this trade, their structure, and the tasks their members perform in their transactions. We will also examine the profile of workers and entrepreneurs in these groups, and the changes that seem to have occurred in recent decades. We will also present some observations about the permanence of the smuggling networks and organisations, their strategies to avoid detection, and the pricing tendencies in this market. This information may help to clarify the importance of networks and hierarchies in illegal enterprises (Morselli, 2001; Natarajan and Belanger, 1998; Ruggiero and South, 1995; Reuter and Haaga, 1989; Adler, 1985; Reuter, 1984), and the nature of the cannabis industry.

Data sources

We use a combination of primary and secondary data sources, including prior studies and reports published by international agencies, data from our ethnographic fieldwork in drug trading environments and our ongoing research and analysis of seizure cases published in the Spanish press from 1976 to 2003. In this period, thousands of illegal deals were prevented. The press reports on these failed transactions provide important insights on the structure of hashish distribution and the character of drug trafficking organisations. We have applied to this topic the methodology of event analysis as it has been developed by historians in their study of collective actions along a wide time span (see Franzosi, 1995; Olzak, 1992; Tilly et al., 1975).

Production and manufacture in Morocco

In the past 20 years, cannabis cultivation has spread in all directions from the traditional areas in the central Rif, where it has been present since the 15th century (OGD, 1996). However, recent crop eradication efforts, together with the effects of a drought in

2005 have led to a strong decline in cultivation from 2004 until 2006. From the early 1980s to the 2000s, the area devoted to cannabis seemed to have multiplied by 20, and doubled every three to five years. There is considerable agreement in the literature about this rising trend in the various estimations available, notwithstanding their disparities (see Labrousse and Romero, 2001). This constant growth occurred despite the well-publicised campaigns by the Moroccan government in the 1990s to eradicate drug trafficking (Ketterer, 2001).

Recently the UNODC has undertaken detailed surveys of cannabis cultivation with the cooperation of the Moroccan government (UNODC, 2004, 2005, 2006). These surveys provide the most accurate data on the extent, characteristics and value of cannabis production in the country today. Table 1 summarises their results.

Most kif, as cannabis is locally known, is grown in four northern provinces along the Rif mountain chain. One province alone, Chefchaouen, accounts for 56% of cultivation, followed by Taounate (17%), Al Hoceima (16%) and Tetouan (11%). A further province, Larache, reported no significant cannabis cultivation following a crop eradication programme in the summer of 2005. In Chefchaouen a quarter of arable land was planted with cannabis in 2005, while in other provinces this share was between 3% and 10%. Cannabis was grown in three out of four duars (villages), mostly in smallholdings. Nearly 90 000 families grew kif, obtaining about half their income from cannabis (Dh 38 900 or EUR 3600). About 760 000 peasants live from this illicit crop (UNODC, 2005) and other estimations are even larger (3). Kif has become a pillar of the economy.

A hectare planted with kif produces 2-8 tonnes of raw plant (2.3 tonnes on average) depending on soil conditions, irrigation, use of fertilisers, etc. The estimated resin production for 2005 was 1 066 tonnes. Productivity varies from year to year, often drastically. This is typical of dry farming conditions in the Mediterranean basin, due to great oscillations in rainfall. Part of the crop is locally consumed, mostly in the form of low-grade marijuana, which has been traditionally smoked in the region since the 16th century (OGD, 1996). Nevertheless, most of the production is exported to European markets in the form of resin or hashish. Programmes for substituting cannabis with alternative crops have failed so far, although significant progress was made from

2004 until the time of publication in 2008. Kif is 12 to 46 times more profitable than traditional cereal crops, such as wheat and barley (Labrousse and Romero, 2001). In fact, some of the best plots, previously devoted to food crops, are now used to grow cannabis, and forest land has been cleared to plant kif.

Manufacturing: from kif to hashish

Farmers sell both raw cannabis plants, and powder (sandouk). According to UNODC, 35.4 kg of raw cannabis are needed to make 1 kg of hashish. Extracting resin powder from plant material increases profits by about 13% (4) (UNODC, 2005). Pascual Moreno offered different estimations. According to his fieldwork, extracting the resin dust from kif would increase profits by up to 66% (5). However, the risks of being denounced to the police also increase (Labrousse and Romero, 2001). Thus, it seems that two out of three farmers sell raw plants to manufacturers and middlemen.

Hash oil is more concentrated and valuable than hashish itself, and is also easier to conceal and to transport. 10 kg of hashish is needed to produce 1 kg of oil. The techniques for hash oil production were introduced to Morocco in the 1960s following Lebanese and Pakistani methods, in what is claimed to be a dual initiative of both foreign and Ketami traffickers to address export demand and to increase the value of their products (Labrousse and Romero, 2001).

Farm prices and export prices

Cannabis offers a good source of income for small farmers in an underdeveloped region, even though the farmer only receives a small part of the retail price of hashish. According to UN data for 2003, farmers sell 1 kg of resin for Dh 1 400, or about

EUR 130. In Spain, the same kilogram could be sold for EUR 2 725 at wholesale prices (UNODC, 2007) or around EUR 4 400 at retail prices (EMCDDA, 2006).

Export prices in Morocco vary considerably, depending on quality, amount purchased, place of acquisition, etc. If bought directly from the farmers, a gram of best quality hashish (sputnik, doble cero) could reach a price of EUR 0.45 to EUR 0.75 (6). Second-or third-rate hashish will get a third of that (Labrousse and Romero, 2001). In our own research we have found prices as low as EUR 0.10 per gram, or EUR 100 per kg for larger quantities. A common price of second-rate hashish would be EUR 0.50 per gram for those who smuggle up to 1 kg. In one field trip to Chefchaouen in 2001, for instance, we knew of three Spaniards who bought 500g of second quality hashish at Dh 8.5, about EUR 0.60, per gram. They felt cheated, because the sample they were shown in advance was of much better quality. However, they retailed most of the batch in Spain at about EUR 4.00 per gram, which paid for the costs of their trip, together with a small profit.

Comparing different sources, including our fieldwork, we estimate that export prices oscillate between EUR 0.10 and EUR 1.00 per gram of hashish. The total country earnings of the Moroccan hashish industry includes farmers' revenues, exporters' profits and remittances from Moroccan traders and dealers abroad. If about 2 200 tonnes of Moroccan hashish were successfully exported in 2003, earnings could be estimated in the range of EUR 1 billion to EUR 1.5 billion. In any case, earnings are multiplied by a factor of 8 to 10 when sold in Europe. Compared with the price paid by consumers, at about EUR 5.4 per gram of resin, the total turnover of the market for Moroccan cannabis could be estimated at EUR 12 billion. Yet most of this is generated in European markets and is invested in Europe.

The commodity chain of hashish: private and public actors

Smallholders in the Rif economy grow cannabis plants both in rain-fed and irrigated plots. They often hire labourers in summer months, mostly in August, to harvest the plant. Once harvested and dried, plant material is sold to middlemen who extract the sticky dust, especially from the tops of the female plants, press it into balls or blocks of hashish and often adulterate it. Intermediaries then stockpile large amounts of the product in central locations such as Tangier, Tetouan, Al Hoceima and Asilah and have the resin sent to Ceuta and Melilla or across the Strait of Gibraltar to Spain. From Spanish locations, the product is then distributed to all European countries directly, or to the Netherlands, which serves as a secondary distribution centre for northern Europe (Korf and Verbraeck, 1993; De Kort and Korf, 1992).

A pyramid-like structure may be at work, with middlemen buying kif or sanciouk from peasants and producing blocks of hashish of different qualities, stockpiling them, and transporting them to storehouses (Labrousse and Romero, 2001).

Cannabis fields are visible from the roads, and there is no attempt to hide them. Every summer, busloads of workers arrive to work in the kif harvest and thousands of tonnes of plant product are moved, apparently within reach of police officers. Bribery may be widespread, and a local joke tells of traffickers who count distances by the number of bribes they have to pay (Labrousse and Romero, 2001; Ketterer, 2001).

Some cannabis resin networks use a legal business as a façade and have no difficulty recruiting from the young and unemployed in what is a poor region. Among the higher echelons, there is evidence that the hashish trade has become industrialised. The Observatoire Géopolitique des Drogues (OGD) notes that hashish exporters are involved in large Moroccan firms in agribusiness, fishing, transportation, and import—export operations. There is some speculation that this would mean a shift away from the Tangier cartels and toward the Casablanca cartels, which are more acceptable to the government because they do not contest state power in the same way (Ketterer, 2001).

Export practices serve to link expatriate Moroccans in different European countries with drug distributors in the target country. Drug money has changed the consumption patterns of the region. Ketterer recently described the scene:

Driving east from Tangier along the Mediterranean coast, the signs of drug power are obvious: heavily guarded villas with strangely stylised pagodas, frequent roadblocks with police looking for the next payoff and an endless supply of young men going about their workdays in the drug business.

Corruption of public officials is part of the operating routine of illegal businesses (Reuter, 1984). In the case of the Moroccan cannabis resin trade, it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that involvement or interested acquiescence of law enforcement officials must be widespread, considering the level of cultivation, storage and export in place. Some scandals have revealed the involvement of powerful actors in the Moroccan political scene. For instance, in November 1995, data from a secret report of the OGD appeared in the French newspaper Le Monde, alleging public sector corruption had reached the highest political levels, including the royal entourage (7). The Moroccan government sued the newspaper. A backlash against the drug trade produced several notorious arrests and trials in the following months and years. These revealed the connections that operated in the hashish trade between public officials and entrepreneurs.

Two major drug traders had become leaders of networks in the north and had become a threat to state power. One of them, Yakhaoufi, was arrested in late 1995. His subsequent trial revealed a sophisticated and massive organisation with international scope. His own organisation transported hashish out of the central Rif, stockpiled it in Tetouan, shipped it to Spain by sea, then delivered it to wholesalers in Amsterdam. In addition to bank accounts in Morocco, Spain, Gibraltar and Canada, along with a yacht and 15 cars, Yakhloufi boasted of personal, commercial and political ties to the Castro regime in Cuba. These ties facilitated contacts with the Colombian cocaine cartels, which craved Morocco's easily penetrable borders as distribution points into Europe. Yakhloufi was sentenced to 10 years in jail and died of an apparent heart attack in 1998. 'He was too dangerous — he knew too much,' said one Tangier street dealer of Yakhloufi's death (Ketterer, 2001).

A second major figure in the cannabis resin trade in Morocco was H'midou Dib. He retains folk hero status in northern Morocco. A former fisherman, he constructed his own port in Sidi Kankouch on the coast north of Tangier, which was an embarkation point for a steady stream of speedboats. Dib constructed an enormous network of loyal foot soldiers and villagers eager to protect him. He supplied jobs, built mosques, delivered social services and kept the despised authorities at bay. Dib was also involved in complex real estate transactions in Tangier, money laundering operations and other elements of organised crime.

The Dib trial revealed other links between drug traffickers and government officials, including two advisors to former governors in the Tangier province, three civilian police colonels, the military police colonel in charge of coastal surveillance and three former chiefs of the Tangier urban judiciary and national security police services. Some of these officials were fired, arrested and tried, but it is clear that the cleansing campaign of the mid-1990s did little to curb the growth of the drug trade or its ties to official Morocco (Ketterer, 2001).

Sociopolitical and ecological consequences

The cannabis industry has had powerful effects on the society of northern Morocco, the ecology of the region and its political relationships with the rest of the country. Cannabis plots have expanded so fast and so far into hillsides that they are causing soil erosion and the destruction of old forests (Bowcott, 2003; Labrousse and Romero, 2001). Moreover, they compete with the best land for traditional food products and now the region is dependent on food imports. On the other hand, the Rif has traditionally been an impoverished region, discriminated against in investment and infrastructure and driven by resentment towards the central government and the accumulation of wealth and power in the hands of a few. In the years after independence, people in the region revolted and were subjugated by military intervention that caused thousands of deaths (OGD, 1996).

Today, the economy of northern Morocco depends heavily on the kif trade and is becoming a society of smugglers, both of people and commodities into Europe, and manufactured goods into Morocco, with multiple links with Costa del Sol real estate business, Gibraltar offshore banks, and Ceuta and Melilla smuggling organisations. Furthermore, the drug trade affects the crime situation in the country. Some networks of drug traffickers are very often involved in other drug-related crimes and activities. Moreover, there are certain crime prevention-related phenomena inherent to the country and its traditions, namely child labour, some involvement of underage recruitment in liberation movements (mostly in the Western Sahara region), trafficking of human beings and smuggling of migrants (UNODC, 2003).

A young, growing and often restless population looks to the other side of the Mediterranean for jobs, money and a better future. As Ketterer (2001) observed, northern Morocco represents a challenge for the Moroccan state. The region has a potent mix of discontent, drugs, organised political opposition and religion. Morocco's drug barons have steadily become a serious crime problem and security threat, and also major players in the domestic political system. Moreover, there is a growing evidence that violent Islamist cells have become involved in the hashish trade both in Morocco and in Spain. Tragically, several major terrorists acts have been funded with hashish money (Wilkinson, 2003). The two most important so far are the bombing in Casablanca in May 2003, which left 32 people dead; and the train bombings in Madrid in March 2004, that killed 192 people and injured over a thousand (8).

The other side of the Strait: smuggling kif into Europe

Hundreds of tonnes of hashish are smuggled into Europe every year from the Rif. This is a multifaceted export—import industry which enriches thousands of people. Balls, blocks and packages of hashish and hashish oil are carried to Europe by speedboat, fishing boat, cargo ships, cars, vans, trucks, small aircraft, and individuals who carry the drug in their bags, their clothes or their bodies (9). Hashish is hidden beneath vegetables, fish, wood and any other commodities crossing the Strait. Lately, Moroccan hashish and Latin American cocaine have been smuggled together, and South American networks are using West African connections with bases in Morocco to smuggle cocaine into Europe.

In Spain most hashish is seized at sea or in coastal areas, including docks, harbours, beaches and local roads. The most common route of entry crosses the provinces of Cadiz and Malaga, bordering the Strait of Gibraltar. However, more and more quantities have been seized as far away as Catalonia in the east, and Galicia on the north-west Atlantic coast, as drug smugglers use both faster and larger boats. One of the reasons for this displacement of smuggling routes may be the stricter control of the Strait trying to curb illegal immigration.

The constant growth of the hashish trade

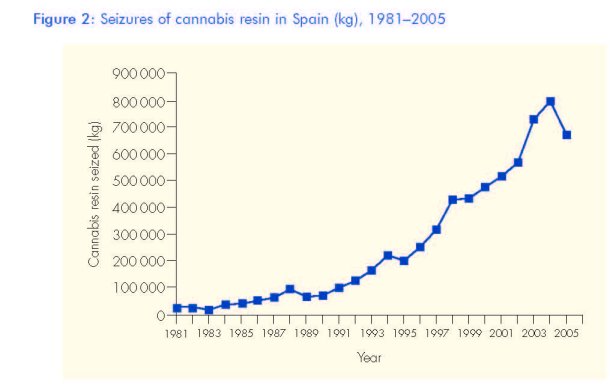

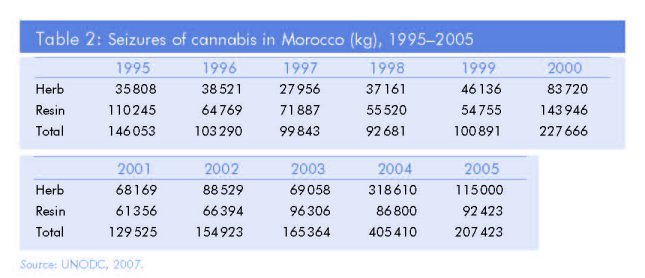

If enforcement agencies' data on seizures are an indicator of this trade, and not of police resources or priorities, the evolution of cannabis seizures in Spain shows the substantial growth of this drug industry in the last 15 years. Spain has recorded a continuous rise in cannabis resin seizures since 1980, reaching over half a million kg a year by the 2000s (Figure 2). Spain alone seizes more hashish than the other 26 countries of the European Union (plus Norway) together. The increase might partly reflect the increase or improvement of police resources. However, the rise in confiscations in Spain parallels the spread of cannabis crops in the Rif, with the moderate tail-off reported for 2005 reflecting the reduction in cultivation reported since 2004. It is thus plausible that the increase in confiscations in Spain is mostly due to growth in the hashish trade. By comparison, seizures in Morocco have fluctuated throughout the last decade (Table 2).

Demand/supply: prices in Spain and Europe

Retail prices for cannabis resin vary greatly within and between European countries (see Carpentier, this monograph), with average prices reported in Europe at between EUR 2.30 (Portugal) and EUR 12.50 per gram (Norway) (EMCDDA, 2006). Average prices of cannabis resin, corrected for inflation, fell over the period 1999-2004 in EMCDDA reporting countries except in Germany and Spain, where prices remained stable, and Luxembourg, where a slight increase occurred (EMCDDA, 2006). In Spain prices tend to increase as one moves north. In Seville or Granada, for instance, in 2003 retail prices of hashish ranged from EUR 2 to EUR 5 per gram, while in Bilbao or Barcelona they commonly ranged from EUR 3.5 to EUR 7. The quality of Moroccan hashish seems to oscillate considerably, although its potency has remained in a range of 5-14%, with little sign that it has increased in the last decade (see King, this monograph). If export prices range from EUR 0.15 to EUR 0.60, retail prices provide a margin of 16-80 times cost. This is an important price differential, and the main incentive for the international trade, but does not seem larger than other drug businesses (see Moore, 1977; Reuter, 1985; Reuter and Kleinman, 1986; Wagstaff, 1989; Reuter et al., 1990).

Event analysis from a sample of newspaper articles

We have applied to this topic an event analysis methodology developed by historians for the study of collective actions such as strikes and social protests across a wide time span (see Olzak, 1989; Franzosi, 1995). In this methodology, events are commonly defined as non-routine, collective, and public acts. The first step in this method is to establish formal rules for coding information on collective events using records from archives, newspapers, historical documents, and police and magistrate records. This allows information on different aspects of a particular type of collective action to be measured and compared across social systems or across time periods, as data are collected in commensurate dimensions (Olzak, 1989).

Historians have observed that newspapers provide the most complete account of events for the widest sample of geographical or temporal units (Tilly et al., 1975) and, despite the limitations of the newspapers as a source of socio-historical data, they often constitute the only available source of information. 'Exclusion of newspaper data would prevent research in fields where no alternative data are available' (Franzosi, 1987). This is especially apt in the case at hand. However, as Franzosi has noted, 'the validity of newspaper information is questionable: newspapers differ widely in their reporting practices and news coverage'. 'The values, routines, and conventions of news organisations constrain the amount and nature of coverage devoted to any story' (Kielbowicz and Scherer, 1986). Nevertheless, in using mass media reports, the type of bias more likely to occur 'consists more of silence and emphasis rather than outright false information' (Franzosi, 1987). In the study of illegal enterprises it is evident 'that no data source is without error, including officially collected statistics', but 'in the absence of systematic and comparative validation, there is no a priori reason to believe that data collected from newspaper would be less valid than other commonly used sources'.

The sample of events

We have reviewed over 2 000 news reports from the newspaper El Pais, concerning cannabis seizures from May 1976 to December 2003. They describe 1 370 failed schemes or projects of smugglers or distributors. On average, these events represent 40.2% of all cannabis seized during this period in Spain, with a considerable variation from year to year (standard deviation: 21.7). In total, our sample includes reports of about one out of every three groups detained in Spain for hashish trafficking in this 27-year period. We chose El Pals for the quality and consistency of its reporting concerning social issues, and because it is the only newspaper that is edited throughout Spain with local editions in all major regions, and, more importantly, because it has indexed all of its issues published since its first edition in May 1976. We have attempted to check the selected cases found in El Pals against other news and police reports of the same events. Our analysis is still ongoing, and the results we present here are provisional and tentative.

The organisation of smuggling and distribution of hash into Spain

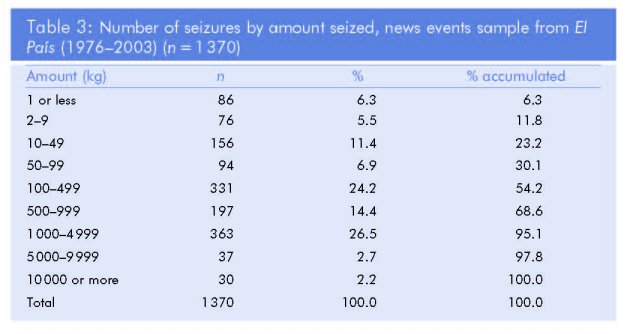

We can draw some preliminary conclusions from our sample of events. In Table 3 we present the number of episodes described in our sample by the amount of cannabis seized. In most cases the substance confiscated was hashish, although some herbal cannabis was also seized, in particular during the 1970s and in the last decade.

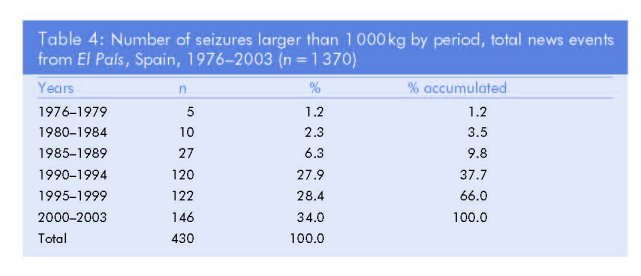

When examining the 1 370 operations we found that over 800 regional distributors and importers were involved. Almost all of those arrested with over 500 kg of hashish were smugglers or large-scale distributors. It is important to note that some of the groups or individuals caught with smaller amounts, even those arrested with less than 1 kg, were also smugglers. Large import operations of 1000 kg or more became more frequent from 1990 onwards (Table 4). This is coherent with the growth of total seizures that surpassed 100 tonnes in 1990 and 1991. In the 2000s, the level of operations seems to have increased even more. We have found data on 430 groups that imported between 1 and 36 tonnes. On average, 3.4 tonnes were seized in these operations, although there is great variation in this sample (standard deviation: 4.5). On average, 7.4 people were arrested by project or police raid (mean: 4.5). The size of these groups varied a great deal (standard deviation: 10.6). In one case, 97 people were arrested in several European countries in a connection with a wide transnational ring of smugglers, distributors and money launderers; in some cases only one person was arrested, for instance, the driver of the truck.

Nationalities of smugglers and traders

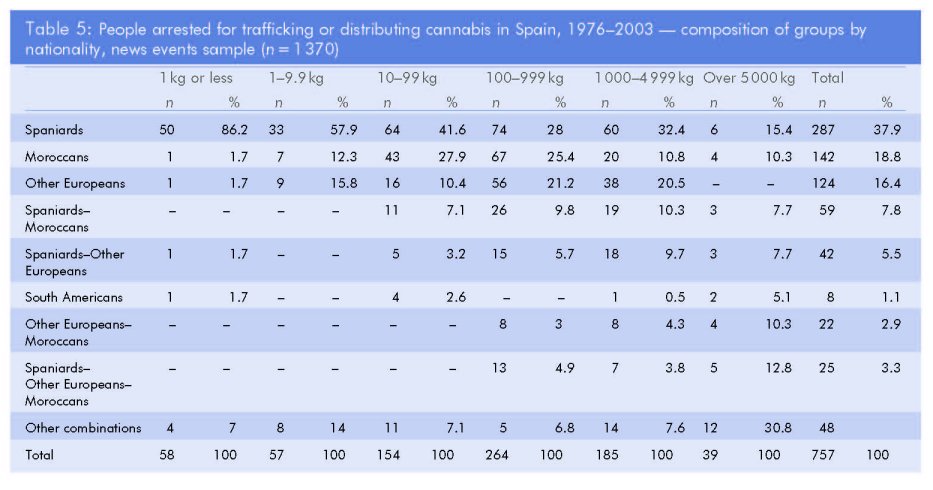

We were able to identify the nationality of people arrested in 757 cases. Over a third of all groups (38%) were formed by Spaniards working with Spaniards (Table 4). Moroccans working with people of their nationality formed the second most frequent type (19%), and groups of nationals from other European countries formed the third most common type. When people from different nationalities cooperated within range of Spanish police, the most frequent combination was that of Spanish and Moroccan nationals (8% of all groups arrested). Spaniards working with other Europeans was also a common type of association, representing 5.5% of all episodes in our sample (Table 5).

We observed a correlation between the size of the haul seized and the nationality of the members of the distribution groups. Furthermore, nationality was linked to the dominant task of the organisation. Almost all retailing is done by Spaniards working alone or

in small groups of same-country nationals. Moroccan immigrants were commonly found in small smuggling and wholesale operations involving less than 100 kg. French, British, Dutch and other Europeans were also important in smuggling these quantities, and sometimes they transported cannabis from Morocco. Often, however, for these quantities the traffickers sourced the cannabis from Spain before shipping it to France, the UK and the Netherlands. In large-scale smuggling, the role of foreigners tends to be proportional to the size of the cargo. Besides Spaniards, French, Dutch and British nationals were commonly involved in smuggling between 1 and 5 tonnes of resin. In the largest, multi-tonne schemes, the groups tended to be more complex and international, and some of the combinations are not reflected in Table 4. For instance, South Americans appeared to be progressively associated with Spaniards and Moroccans in smuggling operations of over 5 tonnes.

We were able to collect information on the nationality of members of 224 groups of importers dealing with one or more tonnes of cannabis resin. Most of these groups were composed of non-Spanish Europeans (40%), followed by groups in which Spaniards cooperated with other Europeans (30%). It is important to note that the data cover only people who were arrested in Spain and do not provide information on all the members of transnational drug-dealing organisations. Thus, it underestimates the level of international cooperation in cannabis trafficking to Europe.

Hashish trafficking and gender

In 280 cases the sex of traffickers was specified, and about 19% were women. Women were especially active in the lower ranges of the hashish trade. Thus, in the groups dealing with 1 kg or less, a third were women working alone or in association with men. In the range of over 1 kg to 50 kg, 29% of all arrestees were women, often dealing in same-sex teams. In the higher echelons of the trade, however — defined as those involving 500 kg or more — less than 5% of arrestees were women, and they always worked in groups led by men. Mixed gender teams were present in all levels of the trade; 11% of all groups were of mixed gender. We found two culturally defined feminine roles culturally sanctioned in the hashish trade — one was sanctioned by the derogatory labels of 'culeras' and lvagineras', or mules who conceal the drug in their rectums ('cub', 'ass') and vaginas. The other involved middle-aged women with grown-up sons and daughters leading family networks in unstructured families and destitute neighbourhoods. Evidently, this is a male-dominated market and women often experience processes of exclusion and exploitation.

Types of organisations and networks

We have found a variety of organisations and networks involved in smuggling and distributing cannabis resin into Europe via Spain. They vary in structure, strategy and main tasks. Case examples of the schemes and groups included in the newspaper corpus serve to illustrate key aspects of smuggling networks, such as their size, tactics, roles, tasks and permanence in the trade. These are crucial elements in the organisation of illegal enterprise (Haller, 1990; Dorn et al., 1992).

The smallest unit of smuggling and distribution

The smallest unit of smuggling and distribution is formed by individuals or by small groups of two or three people who carried the drug in their bags, clothes or within their stomachs, rectums or vaginas. They do not need much investment or organisation, and can repeat their schemes several times every month, or not at all. They are 'freelancers', in the typology proposed by Natarajan and Belanger (1998).

In the early 1980s, trips to the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla in northern Africa or to Tangier or Tetouan to import small amounts of hashish, often within one's own body, became a sort of rite of passage for many novices of the Spanish drug wave.

In slang, the adventure was known as `bajar al moro'. A theatrical comedy and the subsequent film of this title were commercial successes. The film, somehow, reinforced the gendered hierarchies of the trade, as the protagonist had to lose her virginity to be able to make such a trip to a 'Moorish' country. What follows are several examples of this level of trafficking.

Case 1 A 60-year-old 'mule'

In May 1985, a 60-year-old woman went to the emergency room at the hospital in Ciudad Real, a city in central Spain. She could not defecate the 96 10-g 'eggs' of hashish she had swallowed in Morocco. She had to undergo several surgical procedures to extract what had become a large pulp of hashish. She was later indicted for drug trafficking (El Pais, 1 May 1985). This case reflects the not infrequent involvement of older women in the hashish trade. They may transport drugs in order to pay for their family's needs, sometimes with the help of male members of the family.

Case 2 Three Frenchmen who loved oil

Three young Frenchmen bought 80g of hash oil in Tetouan. They sealed it in packages made with condoms, swallowed them, and crossed into Spain through Algeciras. In Multinational export-import ventures: Moroccan hashish into Europe through Spain

Madrid, one of them felt very sick and his colleagues took him to the hospital. The police were called (El Pais, 10 April 1980).

Case 3 An individual multikilo importer

In September 1989, a 28-year-old Moroccan was arrested in Almeria's harbour when getting off the Melilla ferry. He was carrying two suitcases with 45 kg of cannabis resin. He was on his way to Cordoba. Police estimated that the drugs were worth 9 million pesetas, or about EUR 1.20 per gram wholesale (El Pais, 12 September 1989).

Case 4 Small-scale smuggling from Spain into France

In November 1992, four women were arrested in Madrid's Chamartfn train station when they were boarding the Bordeaux train with 32 kg of hashish in their bags. It seems that they were related. Two of them were Spanish, a 54-year-old woman and her 26-yearold daughter, and the other two were French nationals, a 26- and 19-year-old. They were travelling with two babies. They had arrived two days before, exchanged a large amount of French currency in the station bank, took a taxi to Madrid Airport, and flew to Malaga. Upon their return, their bags were searched by suspicious police officers. They had made similar trips in June and September of the same year (El Pais, 26 November 1992).

This appears to be a case of small-scale smuggling from Spain to France. It is possible that these women were wholesalers or retailers in France. There was some continuity in their projects, and they may be an example of a family business, in the typology proposed by Natarajan and Belanger (1998).

Smugglers for multiregional distribution

The second type or level of drug trade organisation includes networks that smuggle hundreds of kilograms using boats, trucks, or even small aircraft. Often they work together with importers or regional distributors in other European countries, and maintain, at least for a period, some continuity in their operations.

Case 5 By air: importation and regional distribution

In February 2000, Spanish police forces were suspicious of wholesalers in four provinces that followed similar routines. They were able to trace a common contact in Seville, and learned of an incoming shipment arriving at a makeshift airfield in the Cadiz countryside. There they seized 639 kg of 'pollen' or high-quality resin, and five high-end cars. A light aircraft made the three-hour round trips from a small airport in Seville to Morocco and back, with an intermediate landing in countryside locations. Seven people were arrested at the landing grounds. The financier and an aide were arrested on their return from Morocco. In the financier's home the police found 40 million pesetas in cash (about EUR 240 000). All arrestees seemed mature, knowledgeable and careful. Their average age was 38. Police found that they had been conducting regular flights to Morocco, often at night, for several months.

This appears to be a case of importers linked to regional distributors and wholesalers, with a clear hierarchy and division of tasks based on resources, contacts and expertise. They seemed to work exclusively in Spanish regional distribution covering a large area. They exhibited some permanence and repeated the same modus operandi over several months.

Large-scale importers for an international market

A higher level of operations is reached when tonnes of hashish are smuggled into Spain and sent to other European countries for wider distribution.

Case 6 Middle-tier distribution network: smuggling to the wider Europe

In March 1977, the British yacht Cynosure was seized in Palma de Mallorca's harbour. In the yacht's stores the Spanish police found over 2000 kg of hash in sealed packages. Two French sailors were arrested on the spot. The captain and owner, a prominent businessman from the Balearic hotel trade, fled but was arrested in Amsterdam some weeks later and extradited. The cargo had been transferred to the yacht from a fishing boat in Betoya's Bay in northern Morocco. The two French sailors had been hired in Ibiza to sail the yacht from Morocco to Southern France. Near Mallorca the engines failed, and in their search for help they provoked police suspicion. There was evidence of previous trips by the Cynosure from Moroccan ports to Southern France, with stops in the Costa del Sol, Costa Brava and Mallorca. Here we see a small organisation, linking Morocco and France, with a minimal hierarchy and distribution of work, and some recurrence in their operations.

The industrial level

The higher level of the cannabis resin export—import industry is composed of groups that deal with dozens of tonnes at a time in industrial scale operations.

Case 7 Large-scale smuggling: an electric train in a cave

The sophistication of the higher echelons of the cannabis resin import industry was revealed in July 1 988 when police discovered one of the largest stashes of hashish on record in a cove near the Costa Brava resort of Lloret de Mar in north-east Spain. Smugglers had constructed a 50-metre tunnel through a mountain that connected the beach to a cabin in a field via a small train. In the tunnel, police found 15 tonnes of cannabis resin. Another 2 tonnes were found in a farm nearby. Air conditioners and humidifiers maintained the hashish's quality, and refrigerated trucks took the product to markets in France, Britain and West Germany. Six people were arrested, all in their 40s and 50s. A Corsican and a Spaniard were the leaders of the group. The Spaniard had already been prosecuted in 1981 when found with 2.5 tonnes of hashish. Police claimed that 'The Corsican', as the second leader was known, was considered the chief of a ring of international smugglers (El Pais, 26 July 1988). He was a French citizen who owned several restaurants on the Costa Brava. One of these restaurants had been attacked with a bomb three years before. His arrest was world news, and he was related to the Corsican Mafia (see Time article, 'Smugglers On Ice', 8 August 1988). In 1992, when the trial took place, it became evident that the group had been operating for some time, and probably was responsible for the smuggling of hundreds of tonnes of hashish (El Pais, 16 July 1992). 'The Corsican' was arrested again in June 1997 in relation to another haul of 6 tonnes of hash seized near Barcelona. Six people were arrested. He had, at the time, been out of jail for less than a year (El Pais, 24 June 1997).

This is an example of a section of an international network, armed and well organised, with credit and capacity to invest in infrastructure and the trafficking of tonnes of cannabis resin in every operation. These traffickers had been in the business for over 15 years, although it seems that much of this time they were inactive.

Case 8 A freight cargo with fish meal

Early in 1996, customs officers in Marini a small harbour in the Galician coast of northwestern Spain unloaded thousands of 10-kg hashish packages hidden beneath fish meal in the storerooms of the Volga One, a 49-metre cargo ship registered in Panama that had arrived that day. Three months before, the same ship, with a different name, had unloaded a legal cargo of 260 tonnes of tuna fish. This time, 36 tonnes of Moroccan hashish were hidden beneath a cargo of 90 tonnes of fish meal. The ship picked up its cargo in Asilah, a small harbour in the Atlantic coast south of Tangier. Most of the eight crew members were Russians. This was the largest seizure of hashish on record, and 11 people were charged. A highly indebted businessman from the Canary Islands, with experience in food imports, appeared to be the financier and the contact with Dutch and Moroccan distributors. A Galician entrepreneur linked to tobacco smuggling and cocaine importers seemed to have organised the shipment and local storage. A trade union leader and a prison officer were also charged. The 'Canario' entrepreneur had USD 2.5 million in cash, mostly in Dutch currency, when apprehended.

Here, we see a coalition of entrepreneurs working together on a large project. Individuals from at least four countries were playing roles according to their expertise and capacity: financiers and buyers of the drug, organisers, wholesalers, ship crews, transporters and Dutch importers. The network they had developed, however, seemed transitory, project-oriented, and non-hierarchical.

In this simplified overview, we have shown the emergent lines of a pyramid that includes various actors performing different tasks in association or competition. Our sample reveals only failed schemes, and of those, only the portion operating in Spain. Obviously, the limitations of our sample are considerable. Further work is necessary to document networks operating in other countries at both ends of the commodity and the financial chains followed by hashish and the money that pays for it. Thus, much work remains to be done in Morocco, Gibraltar, Costa del Sol and in the receiving European countries.

Violence in the hashish market

Violence in the hashish market seems to be much less frequent and serious than in the cocaine and heroin markets, although perhaps in both cases its effects tend to be exaggerated. As Reuter observed, 'there are many limitations on the use of violence as a tool for competition, that only in very narrowly defined circumstances can violence be used to suppress competition' (Reuter, 1984). We found violent acts in three realms of the hashish trade: in connection with large networks in which some associates abandon their duties; in retailing, where some dealers (in Spanish: 'camellos') and clients fight over prices, money, thefts, etc., and when traffickers react violently against enforcement officers. Here we present some examples.

In June 1990, a suspected hashish dealer was arrested in Madrid when he knifed a client in a central square notorious for the drug scene (El Pais, 27 June 1993). In the Costa del Sol there have been some cases of murders related to hashish trafficking, apparently related to unpaid debts (see El Pals, 20 January 1993). In 1996, a 'mule' who did not deliver the drug he was given in Morocco to bring to Spain inside his body was kidnapped (El Pais, 6 June 1996). There was also the case of an international criminal network that poisoned two importers who had apparently sold adulterated hashish. Following this incident, one of the dealers attacked became a police informant (El Pais, 10 May 1994). In another case, a group was using 15-year-olds to smuggle hashish within their bodies from Ceuta, and used intimidation and violence to coerce the minors (El Pais, 11 October 1995).

In our sample, episodes involving violent acts are few and far between, and the atmosphere in the hashish trade does not seem as threatening or violent as that of the cocaine industry. Violence and intimidation may be a means to solve disputes in the hashish market, and to enforce contracts and obligations. But, at least on the European side in Spain, there is little sign that it is used to maintaining monopoly or oligopoly conditions, which would prevent people from entering this trade.

Concluding comments

The market for hashish in Europe has grown substantially in the last three decades and has stimulated the spread of an illicit plantation and manufacturing economy on the other side of the Mediterranean. Today, 22.5 million Europeans are reported to have consumed cannabis in the last year (see Vicente, this monograph). Two major products dominate the European market: a relatively standardised cannabis resin, and domestically or Dutch-grown herbal cannabis. Most of Europe's cannabis resin originates in Morocco and is imported through Spain, and then often taken to the Netherlands to be distributed in northern countries (UNODC, 2007).

Cannabis-related policies are contentious issues in international relations. European countries have often been accused of leniency regarding cannabis use and possession, as occurred in the meeting of the United Nations Commission on Narcotic Drugs (UNCND) held in May 2002. The growing links and transfers of people, commodities and ideas from both sides of the Mediterranean have facilitated the explosion in the production of hashish. The multiple transactions and displacements to and from Morocco facilitate the smuggling of hashish.

The rapid growth of cannabis resin production in Morocco is a dramatic phenomenon. Cannabis resin is the most successful Moroccan export of the last quarter of a century. For northern Morocco it has been a mixed blessing. In the short term, it may be helping to alleviate some social and political tensions, providing a source of foreign currency in a region in which underprivileged, forgotten and resentful citizens are pitted against their government. However, it is also increasing corruption, raising local prices, and cutting incentives for local production of legal crops and other goods. Long term, the drug trade could produce nastier effects if it leads to an increase in the local consumption of hashish and other drugs, or if the European demand for cannabis diminishes and the Rif turns to other crops, for instance opium poppies. Growing links between hashish and cocaine traders may prove ominous.

The structure of drug export-import organisations

From our limited review of importers and distributors arrested in Spain, we will venture some observations concerning the types of organisations and networks involved in the trade. First, the hashish trade, like most illegal markets, is a service industry and 'the bulk of total cost of getting the final good to the consumer is not production but compensation to those involved in the distribution of the drug from production point to the final consumer' (Reuter, 1984). Technologically, the hashish industry is very simple. There is little transnational cooperation in the manufacturing of the product, and chemical precursors are not needed. The hashish industry is mostly a storage and transport industry. Some initial investment is necessary for seeds and fertilisers, and to buy raw material from farmers. As in other drug industries, 'capital in this business consists almost entirely of an inventory which is turned over very rapidly and the "goodwill" built up by knowing good suppliers and customers' (Reuter and Haaga, 1989). Thus, the cost curve of cannabis resin distribution is likely to be determined by human factors (Reuter, 1984).

Second, although our data are partial and preliminary, they echo the findings of authors who have been analysing drug dealing networks or organisations from a relational or industrial organisation perspective. For instance, Reuter and Haaga explored careers and organisations in the upper levels of the cocaine and herbal cannabis markets, and found that successful operations did not require 'a large or enduring organisation'. More or less formal organisations may exist, but are not indispensable for 'operational or financial success'. Relationships between partners 'were more like networks than like hierarchical organisations' (Reuter and Haaga, 1989). Therefore, the relational aspects of the drug industry may play a crucial role in its structure, although few studies have focused on this topic. MorseIli (2001) has recently reviewed the operational methods of a long-term distributor of hashish, and found that he never worked within an organisation but was able to operate via his own strong and weak links within a very wide social network.

As we have shown, the major groups working in smuggling hashish present a hierarchical division of roles and tasks, but this structure seems to be transitory and informal. As Reuter and Haaga noted, asymmetries of information 'would preclude formal organisation' (Reuter and Haaga, 1989). Participants often work as independent specialists or salesmen, hired for one project, more like freelancers or specialists. Thus, MorseIli concludes that 'informal cooperation rather than formal organisation' is a more suitable notion to describe the links of those participating in drug importing (MorseIli, 2001).

In sum, hashish smuggling and distributing firms tend to be informal, changing and decentralised, more cooperative than corporative. As Zaitch (2002) has found concerning cocaine import groups in the Netherlands, hashish trading organisations are more flexible than the notion of a 'cartel' suggests. Some are individual enterprises. Others adopt the form of temporary partnerships between two or three persons who collaborate in a single project. Individuals who function as brokers play a central role in bringing about these coalitions for specific transactions or projects (Zaitch, 2002; MorseIli, 2001; Korf and Verbraeck, 1993). Larger operating groups rarely involve more than nine persons, and the division of labour is not rigid or compartmentalised along vertical lines, and despite the importance of kinship ties and the frequent use of relatives, few of these enterprises are 'family businesses' (Zaitch, 2002).

Our results indicate that the organisations in this trade seemed more cooperative than hierarchical, and were based on network modes of resource allocation where transactions occur neither through discrete exchanges nor by administrative fiat, but through networks of individuals engaged in reciprocal, preferential, mutually supportive actions (MorseIli, 2001). It is probable that the structure of drug organisations is somehow different in Europe and Morocco, for a number of reasons. One area of difference stems from the varying roles of the state institutions and officials on both sides of the Strait. Furthermore, the need to grow, harvest, collect, manufacture and store the product on a yearly basis may promote more stable transactions and, perhaps, networks and organisations in Morocco. However, we know very little direct information about groups based primarily in Morocco.

Competition and disorganised crime

The hashish trade seems relatively open and competitive, although competition seems greater at the lower echelons of the market. There is no evidence of smuggling cartels or oligopolies operating in the Spanish side of the trade, and even the existence of large, stable organisations is doubtful. This is more difficult to ascertain for the Moroccan side.

We know that some entrepreneurs have been able to remain involved in the cannabis trade for decades, but for long periods of their careers they were inactive for their own reasons, or because they suffered arrests, trials and incarceration. In any case, most entrepreneurs seem to work 'without having the organizing force and support of a reputed and resource-yielding criminal organisation' (MorseIli, 2001). Instead, they may rely on legal enterprise for a more permanent business structure and stable contractual relationships for some of their associates.

In some cases, one small group, even a single individual, runs the whole pyramid, buying from Moroccan farmers, smuggling it into a European country and retailing the drug to consumers. But larger operations reveal considerable complexity and coordination of people in Morocco, Spain and other European countries buying, storing and transporting the product through several frontiers and selling it to wholesalers and smaller distributors.

There are competing views of how drug markets are organised. Most studies assume that organised crime plays a major role in structuring these markets through organisations that are hierarchical, relatively permanent and bureaucratic. Some authors posit the existence of 'corporations' in the drug trade. In parallel, there are explanations in which 'violence is typically regarded as the principal regulator of competition' (MorseIli, 2001). This model does not seem to apply to our data. It appears that hashish dealers face few barriers to entry in the low and middle levels of the market, and also in the higher levels if they have the right contacts and funds. A successful operation does not require the creation of a large or enduring organisation, and it is possible to function as a high-level dealer without recourse to violence (Reuter and Haaga, 1989). Moreover, violence and intimidation do not have as much of a presence in the European hashish trade as in the cocaine business. There are cases concerning kidnappings and killings in our sample, but they are rare and usually connected with rip-offs, fights at the retail level or reactions against enforcement officers.

Regarding the origin of the agents of this market, Moroccan hashish importers both compete and cooperate with native Spanish and other European importers, and to a lesser extent with traffickers of other nationalities, which is similar to what Zaitch (2002) has recently found concerning Colombian importers in the Netherlands. All traffickers experience conditions that both promote and limit their opportunities. While some Moroccans may have privileged access to hashish supply, local entrepreneurs tend to have better access to human resources and infrastructure in their countries.

Prices, standardisation of products and economies of scale

Price data are a potentially important research tool for understanding the workings of drug markets and the effects of law enforcement (Caulkins and Reuter, 1998), but its collection has not been a priority in Europe. Thus, we lack historical data on such a crucial variable, which makes it difficult to understand the evolution of drug markets. With regard to cannabis resin and other cannabis products, European evidence shows a clear decrease in real prices, at least from 1 989 to 2004, a period in which there has been a clear increase in demand of cannabis products. This appears to have also happened in other European countries, such as the UK. It seems that international groups which operate in a European common market for cannabis have developed economies of scale, with declining costs per unit of output, and this has resulted in a decrease of prices, the standardisation of supply, and a reduction in the diversity of the final product both in quality, origin and type of derivative.

(1) We want to thank Alicia Rodriguez Marcos for her help in collecting news clips, and Alexandra Bruehl, Aryelle Goins and Isabel Velez for their suggestions and corrections to previous versions of this paper.

(2) In 2004 the GNI per capita of Spain was 14 times that of Morocco; the GNI per capita of France was 20 times that of Morocco. By comparison, the US GNI per capita was six times that of Mexico, its southern neighbour (World Bank).

(3) Pascual Moreno, an agronomist, director of an EU substitution program in the Rif, has worked for 25 years in the region. He estimated that over 200 000 smallholders cultivated cannabis in the Rif in the early 2000s, covering a total area of around 250 000 hectares and affecting from 1 to 1.5 million people (cited in Labrousse and Romero, 2001).

(4) The difference in price is from Dh 3 500 for 100 kg of raw cannabis to about Dh 3 950 for the 2.82 kg of resin obtained from them.

(5) According to Pascual Moreno, 100 kg of kif will get the farmer 5200 Dh. The 3.5 kg of hashish that can be obtained from the 100kg, Dh 8750, a further profit of Dh 3 500 (Labrousse and Romero, 2001).

(6) In 2001 we noted that in a café in Chefchaouen, a lOg egg of good quality hashish retailed at around EUR 1.50 for foreign customers.

(7) See www.ifex.org/en/contentiview/full/60123 for further details.

(8) See, among others, 'La masacre financiada por el narcotrCifico' [The massacre funded by drug trafficking], El Munch:), 15 April 2004.

(9) The World Customs Organisation splits cannabis resin seizures as follows: vessel, 56%; vehicle, 42%; air, 1%; mail, 0.1% (Pierre Bertrand, WCO RILO unit, meeting at the EMCDDA, 29 November 2004).

Bibliography

Adler, P. A. (1985), Wheeling and dealing. An ethnography of an upper-level drug dealing and smuggling community, Columbia University Press, New York.

Bowcott, 0. (2003), 'Morocco losing forests to cannabis', The Guardian, 16 December.

Caulkins, J. P., Reuter, P. (1998), 'What price data tell us about drug markets', Journal of Drug Issues 28(3): 593-612.

De Kort, M., Korf, D. (1992), 'The development of drug trade and drug control in the Netherlands: a historical perspective', Crime, Law and Social Change 17: 123-144.

Dorn, N., Murji, K., South, N. (1992), Traffickers. Drug markets and law enforcement, Routledge, London.

EMCDDA (2006), Annual report 2006, European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, Lisbon.

EMCDDA (2007), Annual report 2007, European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, Lisbon.

Franzosi, R. (1987), 'The press as a source of socio-historical data: issues in the methodology of data collection from newspapers', Historical Methods 20 (1): 5-16.

Franzosi, R. (1995), The puzzle of strikes: class and state strategies in postwar Italy, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

GameIla, J. F., Jiménez Rodrigo, M. L. (2003), El consumo prolongado de cannabis: pautas,

tendencias y consecuencias, Fundaci6n de Ayuda contra la Drogadicci6n, Madrid.

GameIla, J. F., Jiménez Rodrigo, M. L. (2004), 'A brief history of cannabis policies in Spain', Journal

of Drug Issues 34(3): 623-659.

Haller, M. H. (1990), 'Illegal enterprise: a theoretical and historical interpretation', Criminology 28(2): 207-235.

Independent Drug Monitoring Unit (2005), 'The cannabis market', Drug survey 2005 www.idmu.co.uk/ru5.htm

Ketterer, J. (2001), 'Networks of discontent in Northern Morocco: drugs, opposition and urban unrest', Middle East Report Online 218, special issue: Morocco in transition www.merip.org/mer/mer218/mer218.html

Kielbowicz, R. B., Scherer, C. (1986), 'The role of the press in the dynamics of social movements', Research in Social Movements, Conflict and Change 7: 203-233.

King, L. A., Carpentier, C., Griffiths, P. (2004), 'An overview of cannabis potency in Europe', Insights No. 6, European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, Lisbon.

Kingery, P. M., Alford, A. A., Coggeshall, M. B. (1999), 'Marijuana use among youth — epidemiological evidence from the US and other nations', School Psychology International 20 (1): 9-21.

Korf, D. J., Verbraeck, H. (1993), Dealers en dienders: dynamiek tussen drugsbestriiding en de midden- en hogere niveaus van de cannabis, cocaine, amfetamine en ecstasyhandel in Amsterdam, Criminologisch Instituut Bonger, Universiteit van Amsterdam, Amsterdam.

Labrousse, A., Romero, LI. (2001), Rapport sur la situation du cannabis dans Le Rif Marocain. OFDT, Paris.

MacCoun, R. J., Reuter, P. (2001), Drug war heresies: learning from other vices, times and places, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Moore, M. H. (1977), Buy and bust. The effective regulation of an illicit market in heroin, Heath, Lexington.

Morselli, C. (2001), 'Structuring Mr. Nice. Entrepreneurial opportunities and brokerage positioning in the cannabis trade', Crime, Law and Social Change 35: 203-244.

Natarajan, M., Belanger, M. (1998), 'Varieties of drug trafficking organisations: a typology of cases prosecuted in New York City' Journal of Drug Issues 28 (4): 1005-1025.

Observatoire Géopolitique des Drogues (OGD) (1996), Atlas mondial des drogues, Presses Universitaires de France, Paris.

Observatorio Espafiol sobre Drogas (2003), Informe n6mero 6, Noviembre 2003, Ministerio del Interior. Delegaci6n del Gobierno para el Plan Nacional sobre Drogas, Madrid.

Olzak, S. (1989), 'Analysis of events in studies of collective action', Annual Review of Sociology 15: 119-141.

Olzak, S. (1992), The dynamics of ethnic competition and conflict, Stanford University Press, Stanford.

Reuter, P. (1984), Disorganized crime: illegal markets and the mafia, MIT Press, Cambridge.

Reuter, P. (1985), 'Eternal hope: America's quest for narcotics control', The Public Interest 79 (Spring): 79-95.

Reuter, P., Haaga, J. (1989), The organisation of high-level drug markets: an exploratory study, Rand Corporation, Santa Monica.

Reuter, P., Kleinman, A. R. (1986), 'Risk and prices: an economic analysis of drug enforcement', Crime and Justice, An Annual Review of Research 7: 289-340, Chicago University Press, Chicago.

Reuter, P., MacCoun, R., Murphy, P. (1990), Money from crime. A study of the economics of drug dealing in Washington, D.C., RAND Drug Policy and Research Center, Santa Monica.

Ruggiero, V., South, N. (1995), Eurodrugs. Drug use, markets and trafficking in Europe, University College London Press, London.

Tilly, C., Tilly, L., Tilly, R. (1975), The Rebellious Century, 1830-1930, Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

UNODC (2003), Global illicit drug trends 2003, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Vienna.

UNODC (2004), World drug report 2004, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Vienna. UNODC (2005), World drug report 2005, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Vienna. UNODC (2006), World drug report 2006, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Vienna. UNODC (2007), World drug report 2007, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Vienna. Wagstaff, A. (1989), 'Economic aspects of illicit drug markets and drug enforcement policies', British Journal of Addiction 84 (10): 1173-1182.

Wilkinson, I. (2003), 'Morocco: cannabis profits "funding terrorism", Daily Telegraph, 9 August. Zaitch, D. (2002), Trafficking cocaine: Colombian drug entrepreneurs in the Netherlands, Kluwer Law International, The Hague.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|