Chapter Three The Age of Prohibition

| Books - Cannabis: Marihuana - Hashish |

Drug Abuse

Chapter Three The Age of Prohibition

A ban on any substance depends exclusively on the self-seeking choices of those who have an interest in imposing it and the power to do so.

Until the nineteenth century, mind-affecting substances included many euphoriant and therapeutic agents that played an important part in social life and occupied a privileged place in the therapeutic armoury of medical science. Alcohol, tobacco, coffee, tea, opium, marihuana, and cocaine, which were used for a variety of restorative and therapeutic purposes; morphine, which served medical needs; and many other natural products which simply had an invigorating effect made up the wide range of mind-affecting substances that were freely available until the end of the nineteenth century.(77)

Alcohol and opium and its derivatives have been widely used all over the world for thousands of years. Coffee was discovered in Arabia and tea in China, whence they came to America via Europe. Columbus discovered tobacco on his first voyage to America and brought it back to Europe. Marihuana was the biggest agricultural crop on the planet and served a wide range of needs. Coca was initially discovered in Mexico and soon found to exist in vast areas of Central and South America. Morphine is an alkaloid of opium that was isolated in 1805.(78)

The existence of all these substances was not a `threat to society', nor was their use by the free choice of any individual perceived as an `antisocial activity'. On the contrary, all these agents of pleasure or of therapy were socially accepted and quite in keeping with the needs and the values of Western society in the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries, because they enhanced their consumers' sociability and efficiency.

Most of the major drugs that affect behaviour - in particular, marihuana, opium, and cocaine - were used to enable men to work better, harder, and longer. These drugs were to pretechnological man what machines are to technological man: they helped him to increase `productivity' or `output'. These facts have, of course, been brushed aside - indeed, they have been denied and falsified - by the evangelists of our modern pharmaco-mythologies.(79)

The supposed threat posed by drugs was invented later to justify the banning and persecution of certain substances in the service of specific economic and political interests. Unlike a ban, which automatically creates a black market and promotes the use of adulterated mind-affecting substances (which is directly detrimental both to users and to society as a whole), social acceptance and legality have always operated as a safety valve that protects both users and society.

Before the rabid campaign of persecution and repression that has swept the world in the twentieth century, many people in America and all over the world found serenity, euphoria, pain relief, and a remedy for a number of ailments in natural mind-affecting substances, which made their lives more bearable or more agreeable. Whether as popular remedies or as euphoriants, opium, cocaine, cannabis, and their derivatives were highly prized by the medical world and were the substances of choice for many people for centuries on end, from the mediaeval serf to the modern industrial worker.

The free availability of mind-affecting substances and citizens' right to decide for themselves which, if any, of these substances they wished to consume or avoid, and how and when they would do so, came to an end in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, when the state stepped in. Using the weapons of police and penal coercion and state-arbitrated moral pretensions, the administration arrogated to itself the sole right to decide which, if any, substance its citizens would consume, and when, depending on which particular economic and political expediencies it wanted to serve at any given moment.

The intervention of institutionalised constraint in the sphere of mind-affecting substances and the concomitant suppression of citizens' fundamental right to decide for themselves whether or not they would consume any of these substances upset the established equilibrium between the substances, their consumers, and society destroyed the self-regulating mechanisms that protect individuals and society, and created a functional vacuum which enabled the state to present itself as the only agent capable of filling it and to multiply the prohibitions ad infinitum.

Before the state intervened, the individual's relationship with mind-affecting substances was a matter of personal choice and responsibility, an area in which complete freedom was exercised. Afterwards, the individual's relationship with the various mind-affecting substances became regulated by a body of laws and social policies that served a variety of ulterior motives and were born of the authoritarian notion that citizens are incapable of handling mind-affecting substances like responsible adults.

It is a notion that has been forcibly internalised and is now constantly regurgitated by thousands of infantilised adults, who implore the parent state to treat them like irresponsible babies and protect them from, of all people, themselves. To turn the state into a parent-figure and society into so many infants has always been the aim of all administrators of lawful violence, whatever their ideological and political stripe. All that changes is the means used by the power-crazed, which vary according to their needs and the technical possibilities of each particular age.(80)

After the ban on opium-smoking (1875-1902), which served as a pretext for subjugating and manipulating the Chinese immigrants to the United States, and the Chinese immigration ban of 1902, the so-called `drug threat' was trotted out to justify the United States' initial sortie into the sphere of international policy (with the imposition of American control in Puerto Rico, Cuba, Guam, and the Philippines after the war between America and Spain in 1898).(81)

The leading political and economic circles in the United States then realised the enormous importance of prohibiting certain mind-affecting substances as a tool of domestic and foreign policy, and started to wield it extensively. In a matter of sixty years (1875-1937), a combination of economic and political interests had banned opium smoking (1875-1902), all opiates and cocaine (1914), alcohol (1920), and cannabis (1937).

The active intervention of the authorities in an area of personal choice and responsibility actually created what has since become known as the `drug problem'. This so-called problem has in fact merely meant that the relationship between the individual, society, and mind-affecting substances has been reduced from a question of the free choice and responsibility of each individual to a matter to be regulated by the authorities. It is regulated by force by the simple expedient of transforming a means of pleasure or self-therapy into a `threat' to the individual and to society.

1. A tool of domestic policy (1900-30)

In the United States cannabis was a freely available, socially acceptable, and widely used euphoriant and therapeutic agent until the end of the 1930s. This is attested by the fact that every edition of the official US Pharmacopoeia from 1850 to 1942 lists it as a safe remedy for a wide range of maladies.

The leaves of the female cannabis plant were first smoked in the western hemisphere in 1870, on the West Indian islands of Jamaica, the Bahamas, and Barbados. The custom was then brought to North America by Mexican and black sailors. The first written record of the use of marihuana in the United States dates from 1903 and comes from the Mexican community of Brownsville, Texas; the next dates from 1909, in the black community of Storeyville in New Orleans, which is regarded as the home of jazz.(82) After 1910 the use of marihuana began to spread into the communities of Mexican and black workers in Texas and Louisiana, and it later became associated with the jazz world, which facilitated its spread amongst Whites.

During the first decade of the twentieth century, the Mexicans and blacks who were living in the southern states under a harshly racist legal regime began to demand better living conditions.

Between 1884 and 1990, 3,500 documented deaths of black Americans were caused by lynchings; between 1900 and 1917, over 1,100 were recorded. The real figures were undoubtedly higher. It is estimated that one-third of these lynchings were for insolence, which might be anything from looking (or being accused of looking) at a white woman twice, to stepping on a white man's shadow, even looking a white man directly in the eye for more than three seconds, not going directly to the back of the trolley; etc. It was obvious to whites, marihuana caused Black and Mexican viciousness or they wouldn't dare be insolent; etc. Hundred of thousands of Blacks and Chicanos were sentenced from 10 days to 10 years mostly on local and state chain gangs for such silly crimes as we have just listed.(83)

In the circumstances, certain powerful economic factors realised that a ban on marihuana could be used as a means of marginalising and oppressing the underprivileged black, immigrant, and working-class communities and bringing them to heel, just as had been done in the past with the Chinese and the ban on opium smoking. Cannabis was not likely to prove an exception to the standard rule that penal control of a substance is a precondition for penal and political control of its users.

According to the racist propaganda that found fertile ground amongst the whites, "Mexicans and blacks under marihuana's influence were demanding humane treatment, looking at white women, and asking that their children be educated while the parents harvested sugar beets; and other insolent demands. (84) By blaming marihuana for the black community's efforts to improve their situation, the whites could justify all their own atrocities against them.

And so began the first smear campaigns against cannabis led by the Hearst Group's yellow press. Their main target, of course, was the black and Mexican workers. The upshot was that various states (led by Utah and California in 1915 and Colorado in 1917) adopted measures that criminalised possession and use of cannabis and thus paved the way for a process of prohibition that grew all the more easily from the 1920s onwards in the climate of repression created by the folly of alcohol prohibition (1920-33).

By 1917, penalties for using cannabis had been instituted for the first time in Egypt (1879), Greece (1890), and Jamaica (1913). The penalties were those applicable to a misdemeanour, were imposed for cannabis use only by the lower social classes, and were justified on the grounds that it was associated with unacceptable or objectionable social conduct (vagrancy, social parasitism, etc.). But two countries, which had a similar domestic policy of discrimination, began to adopt penal measures against cannabis on the grounds that it was necessary to stamp out `black insolence': South Africa (1911) and the United States (1915) were subsequently to lead the campaign for the prohibition of cannabis all over the world.(85)

However, until the early 1930s, which brought the technological and economic changes that necessitated cannabis prohibition for the benefit of the economic behemoths which controlled the new technologies, cannabis was a fundamental stabilising factor in the US economy and its products covered a wide range of everyday needs. This forced the federal government to adopt a Janus-faced policy towards cannabis in order both to shield the racist and economic expediencies served by the ban on marihuana in the Deep South and to promote the cultivation of cannabis in the north-eastern states by producing special Department of Agriculture leaflets exhorting farmers to intensify their activities in this particular sector of productions.(86)

The authorities and the medical community were well aware that cannabis and its derivatives were non-narcotic therapeutic agents of enormous value. This is precisely why they were not included under the restrictions imposed by the Harrison Bill of 1914, which instituted controls over the supply of narcotic substances (opiates and cocaine) used for medical purposes.

Between 1900 and 1920, American consumers were more interested in cannabis' therapeutic properties (which meant that cannabis products were legally prescribed for a host of physical and psychological dysfunctions right up until 1940) than in its euphoriant effects. But during the period of alcohol prohibition, from 1920 to 1933, they began to show increasing interest in precisely these euphoriant effects, since cannabis was a cheap, harmless substitute for the alcohol they were no longer permitted to consume. So, `during the 1920s, marihuana tea pads - late-night smokeries similar to bars - operated in many large cities, including New York City', which were much like to the bars and coffee houses found in The Netherlands today.(87)

2. A tool of foreign policy (1900-30)

Following the extremely instructive experience with opium and the passage of the Harrison Bill in 1914, the US Government fully appreciated the enormous importance of the `war on drugs' as an auxiliary tool both in implementing the domestic policy designed to manipulate minorities and the working class and in consolidating the expansionist foreign policy designed to gain control over other countries.(88)

After the economic crisis of 1893, the United States entered a phase of explosive development, which demanded a large-scale sortie into new markets. This necessarily presupposed the abandoning of the isolationist Monroe Doctrine and active US involvement in the international political scene.

In this context, the supplying of aid to certain countries to address the non-existent threat of drugs proved a most effective tool of political influence and control on two occasions.

It was in 1898 that the United States first adduced the `necessity' of addressing the so-called drug threat to justify indefinitely postponing recognition of the independence of Puerto Rico, Guam, Cuba, and the Philippines and imposing US control over them (as Spanish colonies, they had rebelled and fought as US allies during the American-Spanish War of 1898 in the hope of winning their independence).

The Filipinos, having fought side by side with American troops to drive out the Spanish, thought that the United States was going to free the islands and turn the government over to them. It was difficult to convince them that the Islands were not yet ready for self-government.(89)

The same excuse was employed again in 1900, to justify US intervention in China during the political and diplomatic clashes between the great powers, who were trying to redistribute their spheres of influence there after the nationalist and anti-colonial Boxer Rebellion had been put down.

Having drawn the necessary lessons from these two cases, in 1908 the US devised the need for a `worldwide crusade' against opium and its derivatives. In 1912 (at The Hague Conference) the United States undertook to lead this crusade, which, in 1925 (after the Geneva Conference), also began to target cannabis.

Until the second Conference on Opium, which was held in Geneva in 1925, the United States had been absorbed in its efforts to convince the other countries of the need to take steps against opium and had shown no interest in cannabis. But during the proceedings, the delegates from Egypt and Turkey (two countries where the cultivation of opium was a major factor in the agricultural economy and which consequently had much to lose from the ban the US was urging) tried to create a diversion by announcing that they would not subscribe to the condemnation of opium if the same treatment were not first applied to cannabis. They were counting on the disagreement of the other countries.

Not unexpectedly, Turkey and Egypt's demand was met with resistance from most of the other delegates. But the US, determined to achieve its aim as far as opium was concerned, supported the demand and (owing to the political and material advantages it enjoyed as the only country to have emerged economically powerful from the First World War) leaned heavily on the other countries' means of economic blackmail, the US eventually forced the participants reluctantly to accept the idea of a possible ban on cannabis for purely political, and not medical, reasons.(90)

So the United States found itself spearheading a campaign against both opium and cannabis together, which enabled it to impose its undisputed domination in the `war on drugs' and to maintain it until the 1970s, when some countries (such as the United Kingdom and The Netherlands) realised the disastrous consequences of prohibition and repression and decided to take steps that went directly against the American anti-drug policy.

3. The reasons for prohibition (1930-40)

The fate of cannabis was decided solely by the combination of political, economic, and technological changes that took place in the 1930s. The plant's multitude of advantages and applications made it an appreciable, if not the only, rival to the products of a number of industrial sectors (petroleum, alcohol, tobacco, pharmaceuticals, paper), which all joined in a concerted effort to have cannabis criminalised over a period of ten crucial years (1926-36) that were marked by five landmark events.

These were:

the creation of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN) in 1930;

the end of alcohol prohibition in 1933;

the invention of high-technology machines to produce paper from timber and the monopolising of the paper industry by the Hearst Group (1930-6);

the mass influx onto the market of petrochemical products (1926-36) and nylon (1935); and

the discovery by the pharmaceuticals industry of the means of producing mass synthetic medicines (1928-32).

All these major breakthroughs took place over a ten-year period and sealed the fate of cannabis, which was the chief threat to their products.

1) In 1930, the Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN) was set up. It was staffed by former prohibition agents under the notorious Harry Anslinger and played a leading role in the processes which led to the outlawing of cannabis in 1937. Sixteen years after the ban on opium and opium products (1914) and ten years after the prohibition of alcohol (1920), the terrible slump of 1929-31 led Congress to slash the FBN's budget and to reduce the number of its agents. Anslinger was terrified that the bureau would collapse. In the circumstances, the newly established bureau, which had not had time to demonstrate the `usefulness' that would justify its place in the national budget, considered it as a matter of survival, prestige, and power to discover a new threat from which society needed its protection. This is why Anslinger and his officers in their new posts completely ignored opium and alcohol and trained their guns right from the start on cannabis, which they foresaw would open up a wide new field of activity for them.

An executive officer for alcohol prohibition until 1930, Harry Anslinger was Director of the FBN(91) from its foundation in 1930 until 1962, when President Kennedy forced him to retire because he had tried to censor the publications of Professor Alfred Lindesmith and to intimidate Lindesmith's employers at Indiana State University. (92) He was appointed to the FBN at the suggestion of Andrew Mellon, owner of one of the two banks with which the DuPont empire was associated.(93) Anslinger's activities as Director of the FBN were wholly determined by his commitment to DuPont, his extreme right-wing and racist views, (94) and his admiration for Edgar Hoover and the FBI. He copied the organisational structure, the manner of operation, and the work style of the FBI and in his hands the FBN became the most effective tool for the institution and preservation of prohibition in accordance with the interests of his `bosses'. After he retired, Anslinger presented his personal records, covering the thirty-one years of his absolute reign over the realms of repression, to the State University of Pennsylvania.(95)

2) IN 1933, the Eighteenth Amendment to the US Constitution, which had ushered in alcohol prohibition in 1920, was repealed and the production, sale, and purchase of alcohol became legal again.

The main market rival to alcohol was the products of cannabis. And the newly established alcohol industries, in which were invested some of the profits from the organised crime that had controlled the distribution and trafficking of bootleg alcohol during Prohibition, had a vital interest in seeing these competing products wiped out.

3) IN 1935, the American company DuPont (96) put non-recyclable nylon on the market and in 1937 acquired the patent.(97) The new product's sole rival was recyclable cannabis, and consequently nylon's survival depended on whether or not DuPont could dislodge cannabis from the market. As Lammot DuPont conceded, `synthetic plastics find application in fabricating a wide variety of articles, many of which in the past were made from natural products.(98)

4) IN 1936, DuPont managed to secure the monopoly on the petrochemical products whose patents had been ceded to the US by the German company I. G. Farben as part of Germany's reparations after the First World War. By this means, 30% of the mighty 1. G. Farben passed into the ownership of DuPont.

The main rival to the various products of the petrochemical industry (paints, dyes, machine oil, and fertilisers, amongst many others) was cannabis and its products, and consequently the DuPont industrial behemoth had a vital interest in seeing them banned. Without the prohibition of cannabis, 80% of the DuPont empire's businesses could not exist.

5) IN 1936, 70% of the paper produced in the United States by felling timber and destroying forests was in the hands of the companies owned by the `robber press baron' William Randolph Hearst.(99)

Prior to 1883, 75-90% of the paper used all over the world was made from cannabis. Cannabis paper is cheaper, of higher quality, and more durable than the paper that began to be produced when technological progress made it possible to fell timber on a large scale and destroy whole forests. In the thirties, cannabis was the Hearst group's number one competitor.

6) AT THE SAME TIME, by the mid-thirties, technological advances were enabling the pharmaceutical industry to manufacture chemical products in the laboratory, with the result that companies in this sector ceased to process and sell natural pharmaceuticals and became independent manufacturers with exclusive control over the products made in their labs.

Everyday therapeutic practice in modem times had been dominated by two broad categories of natural healing agents: the products of opium and the products of cannabis. Opium products were eliminated from the therapeutic field by the Harrison Bill of 1914. Consequently, in the thirties the only rival to the pharmaceutical industry's chemical products was cannabis and its products. The consolidation of the pharmaceutical industry's interests and the transition to the era of universal medical chemical poisoning necessitated the ostracising of cannabis from the field of medicine. To achieve this goal, the pharmaceutical industry worked hand in hand with the other industrial colossi and the medical closed shop.

This perfect dovetailing of the interests of the FBN and the petrochemical, alcohol, pharmaceutical, and paper industries sealed the fate of cannabis to the advantage of this bloc of society's `protectors' and to the disadvantage of cannabis itself, the public interest, and humanity in general. It was an unequal battle and the outcome a foregone conclusion: for the survival and increasing power of the FBNs, the DuPont, the Hearst, and the pharmaceutical and alcohol industries' empires demanded that the cultivation of cannabis cease and its use be banned in all sectors of industry - with catastrophic consequences for the environment and the world economy.

In 1935, under the guidance of DuPont executives and the Hearst Group's network of yellow-press newspapers, the FBN launched an extensive propaganda campaign against cannabis, which prepared public opinion for its forthcoming prohibition.

In 1937, the overlapping interests of the offended industrial sectors, led by DuPont and Hearst, used theirinfluence with the government and the administration to have cannabis banned under the Marihuana Tax Act.

On paper, this act imposed a tax in the form of a special stamp that had to be affixed to any medical prescription containing cannabis products; in practice, however, it penalised the cultivation, possession, use, and distribution of cannabis and its derivatives. The stamp was exclusively issued and supplied by the Treasury, which saw to it that "the stamp was never available for private use." (100)

The passage of this new act made it easy for cannabis to be replaced as a raw material in the textile industry by the petrochemical products on which DuPont now had the monopoly, having acquired the patent from I. G. Farben; and it also enabled DuPont to enjoy almost total dominance in all related sectors of production. At the same time it safeguarded the interests of the Hearst Group as the uncontested monopolist of paper production.

Fifty percent of all the toxic chemical fertilisers that are used today in the agricultural production of the US and most other countries (poisoning the soil, the water sources, and the environment in general) are used for the cultivation of raw materials for the textile industry to the exclusive advantage of the companies, with DuPont in first place, that control the production and supply of the fertilisers themselves.

Whereas cannabis had been a benison of nature for thousands of years, on the pretext of `protecting society' its production was now prohibited and it was banned from the market. The Marihuana Tax Act of 1937 `normalised' the US (and by extension the world) economy to the benefit of the centres of economic and political power that set the United States' course. It took the alliance of the most powerful blocs in the US economy into a paradise of continually accumulating, enormous profits, while humankind entered a hell governed by chemicals and plastics.

4. The State in favour of cannabis (1942-5)

During the Second World War, after Japan had invaded the Philippines, the United States suddenly found itself cut off from the source of a raw material, which, though banned, was nonetheless of great importance for the nation's war effort. From cannabis were made the parachutes, the tents, the kit-bags, the flags, the fatigues, an extremely useful fuel, various fertilisers, and all sorts of other supplies and equipment used by the army and the air force.

The American government addressed this state of necessity by putting its self-imposed ban on the back burner, and setting its 'anti-drug' fervour aside for the time being. From one moment to the next, it stopped persecuting and started defending cannabis, transformed it from a `murderer of young people' into `hemp for victory', and did all it could to urge farmers to grow it.

Until the United States joined the war, any farmer who dared to grow a single cannabis bush was treated like a criminal by the judicial system and regarded by the FBI and the FBN as a threat to the nation. After the United States joined the war, the American government started exhorting farmers to grow as many acres of cannabis as they wanted, presenting it as a patriotic duty.

1) In 1942, the US Department of Agriculture circulated numerous advertising leaflets and made a special propaganda film about cannabis - significantly titled Hemp for Victory - which was shown repeatedly throughout the United States.(101)

2) In 1942, the US government issued a five-dollar tax stamp on cannabis, and aimed to increase the extent of cannabis cultivation to 1,400,000,000 m2 in 1943.(102) It also supplied farmers with very cheap machinery especially for cannabis cultivation. And most astonishing of all:

3) Between 1942 and 1945, every farmer who agreed to grow cannabis for the state was exempted from military service, as were his sons.

After the war, prohibition hysteria returned with a vengeance, drawing even greater strength from its alliance with the reds-under-the-bed phobia, inflamed by the high noon of McCarthyism. Once again cannabis became a `murderer of young people' and a `threat to the nation'.

From then on, for several decades, the Government and the powerful financial interests subjected society to a systematic process of brainwashing by means of repeated campaigns against cannabis. The effect was that "public attitudes towards the use of marihuana were generally marked by hysteria and exaggerated claims of disastrous individual and social consequences of the use of the drug „(103)

Under the pressure applied by Harry Anslinger and the yellow press, the states began to institute increasingly severe penal sanctions for mere possession of cannabis, and in some of them, indeed, persecution reached fever pitch. In Louisiana, for instance, "the penalty is death on the first offence, but if the jury recommends mercy, then there is a mandatory sentencing of thirty-three years to life imprisonment. Thus, in Louisiana a twenty-one-year-old man who is caught giving some pot to his twenty-year-old girlfriend may be legally executed" (104) while Texas instituted "sentences up to life in prison with ten and twenty-year sentences because they were caught with a few marihuana cigarettes.(105)

In the years following the Marihuana Tax Act, Anslinger and the FBN carried out numerous propaganda campaigns and gradually instilled public opinion with a completely distorted image of cannabis based on three fundamental misconceptions: that the use of cannabis impels people to commit violent crimes; that it leads to the use of heroin; and that it poses an enormous threat to society.

The demonising and terrorising activities carried out by the FBN, which acted like a state within a state as far as public life was concerned, stifled at birth any inclination to resist the anti-drug policy of Anslinger and his bosses. An attempt by the medical profession to react against the FBN's totalitarianism ended in an ignominious compromise: the AMA requested that the FBN not be allowed to remove cannabis from its therapeutic arsenal after 1937, and Anslinger, being responsible for seeing that the Marihuana Tax Act was observed, responded with a stream of prosecutions of doctors. On the FBN's initiative, in 1939 alone 3,000 members of the AMA were prosecuted for illegally prescribing marihuana. The blackmail campaign had the desired effect and the medical profession reached a compromise with Anslinger: over the next ten years (1939-49), the FBN instigated legal proceedings against only three doctors, while the official organs of the medical profession uttered never a word on the subject of cannabis. (106)

It is a long-standing truth that has been confirmed over and over again in the course of history that, whenever professional repressionists and the members of the prohibition brigade are confronted with an obvious discrepancy between the mendacity of those in power on the one hand and the conclusions of experience and scientific knowledge on the other, they typically adopt a schizophrenic double-talk, which is extremely alarmist when addressed to the public and moderately frank when addressed to specialists.

The professional repressionists (of other people's liberties) used this ploy ad nauseam in order to negotiate the obstacle of the manifest discrepancy between the stereotype of cannabis projected by the theorists of its persecution and the scientific facts adduced by many intellectuals, scientists, and politicians.

During House hearings, the following exchange between the Michigan representative John Dingell and Harry Anslinger, Director of the FBN, is revealing:

Mr Dingell: I am just wondering whether the marihuana addict graduates into a heroin, an opium, or a cocaine user.

Mr Anslinger No, sir; I have not heard of a case of that kind. I think it is an entirely different class. The marihuana addict does not go in that direction.(107)

6. The challenge to Prohibition (1960-80)

People's accumulated observations and experience over thousands of years made it possible to assess and use the valuable, and in some cases unique, therapeutic properties of cannabis. (108)

Until the end of the thirties, cannabis was acknowledged as an indisputably valuable, harmless therapeutic agent which enjoyed the approval of the medical profession, the unqualified acceptance of the State, and the interest of the pharmaceutical industry, which latter was not yet in a position to manufacture synthetic medicines that could substitute for the natural derivatives of cannabis in certain therapeutic applications.

The State's attitude to cannabis was in complete accord with that of the medical profession. This is proved beyond all shadow of a doubt by the fact that every edition of the Pharmacopoeia of the United States from 1850 to 1942 lists it as a harmless medicament suitable for a wide range of ailments, and the US National Formulary and Dispensatory likewise have precisely the same attitude towards it. (109) The pharmaceutical industry's interest was directly related to the medical profession's and the public's demand for a safe, effective, highly rated medicament. This much is clear from the fact that a considerable number of pharmaceutical products based on cannabis had been on the market ever since the end of the nineteenth century, patented by such major names as Parke Davis, Squibb, Eli Lilly, and Burroughs Wellcome.

The course of events took a completely different turn in the thirties, with the establishment of the FBN, the passing of the Marihuana Tax Act, and the witch-hunt that followed. Yet the effusion of police and penal repression did not completely halt scientific research into cannabis.

At the beginning of the forties, Robert Adams managed to isolate the active substance in cannabis, tetrahydrocannabinol, and opened up the way to more precise laboratory studies that led to a gradual revision of the scientific world's attitude towards `grass' and public opinion about it.(110)

The year 1944 saw the publication of America's first ever scientific report on marihuana, the fruit of five years of research by the ad hoc committee set up by the Mayor of New York, Fiorello La Guardia, in association with the Medical Academy of New York."(111)

Of the thirteen conclusions reached by the sociological-study branch of the report, two are of special relevance to the issue of crime: 1) Marihuana is not the determining factor in the commission of major crimes. 2) Juvenile delinquency is not associated with the practice of smoking marihuana.(112)

The publication of the committee's findings could have triggered a process that might have led to the abolition of the penal and medical control of marihuana imposed by the 1937 Marihuana Tax Act. Such a development would have gone directly against the interests of the politico-medical network of the bureaucrats who handled the medical guild's affairs, not to the doctors' but to the state's advantage. The AMA was therefore quick to oppose publication of the report, calling upon the authorities to disregard the study and "continue to regard marihuana as a menace wherever it is purveyed".(113)

In the early fifties, Cold War hysteria helped the secret services to associate illegal drugs with the `Communist conspiracy':

Congress decreed mandatory minimum sentences for narcotic offenders in an emotional atmosphere similar to the years of the first Red Scare. Hale Boggs's bill, which contained mandatory sentences, was passed in 1951 at the beginning of the McCarthy era and fears of Soviet aggression, the `betrayal' of China to the Communists, and suspicion of domestic groups and persons who seemed to threaten overthrow of the government. Narcotics were later associated directly with the Communist conspiracy: the Federal Bureau of Narcotics linked Red China's attempts to get hard cash, as well as to destroy the Western society, to the clandestine sale of large amounts of heroin to drug pushers in the United States.(114)

The penal sanctions for offences covered by the drug legislation became horrifically harsh and all research into the therapeutic uses of cannabis came to a complete halt, not to be resumed until ten years later, when the draconian restrictions slackened somewhat.

Under Hale Boggs' Bill, which was passed in 1951, when the morphine-addicted Senator McCarthy (whose supplier was none other than Anslinger himself)(115) was at the height of his power, possession and use of any illicit substance was punishable by a term of imprisonment ranging from five years to life, depending on whether it was a first or a second offence. The sale of heroin by adults to minors under eighteen carried the death sentence.

But despite the intensity of the persecution, at the end of the fifties marihuana and various other mind-affecting substances began to gain a certain popularity amongst middle and upper-class young people, whose social position and level of education made them less receptive to the wild scaremongering of the FBN's anti-cannabis propaganda. It soon became apparent that the repressive absurdity of including cannabis in the same category as addictive substances, banning it, and persecuting its users was in fact promoting, rather than preventing, its diffusion and helping to link it with the protest movement which sprang up in North America and spread all over the world in the 1960s.

The emergence of cannabis from the ghetto to which its persecutors' holy fervour had consigned it led to a change of attitude in a large segment of the population and reactivated the scientific world's interest in it. So, as young people were discovering the euphoriant properties of cannabis and promoting is use as a gesture of defiance against the conformist adult world, the medical profession was rediscovering its therapeutic properties and advancing increasingly persuasive scientific arguments that completely pulverised the prohibitionists' fictions.

These two mutually defining processes had a decisive influence on society's gradual change of attitude towards illicit substances in general, not just towards cannabis, which is not a narcotic in the medical sense of the term.

IN 1965, the United Nations' Drugs Commission published a catalogue of 2,000 studies of cannabis, 377 of which had been carried out before 1623 and the rest after 1900. As far as the scientific studies are concerned, an average of 120 titles per decade were published between 1880 and 1929, 300 titles per decade between 1930 and 1959,(116) and 500 titles per decade after 1961. Between 1965 and 1980, more than 3,000 research studies on cannabis were published.

IN 1967, the US government financed a wide-ranging, long-term research programme on cannabis to the tune of five million dollars. It involved one thousand researchers from all over the world working on sixty research projects, under the aegis of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, a government organisation which is part of the US Department of Health. The NIDA published the findings of that mammoth effort nine years later, in 1976.(117)

IN 1968, the British government's Advisory Committee on Drug Dependence published its report on cannabis, commonly known as the Wootton Report, (118) which was described by most of the scientific community as `one of the first contemporary attempts to summarise our state of scientific knowledge and to review the social implications of cannabis use'.(119)

IN 1970, the Canadian government's Commission of Inquiry into Non-Medical Use of Drugs, known as the LeDain Commission, published its important Interim Report. (120)

IN 1970, Lester Grinspoon, Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, published his pioneering study, Marihuana Reconsidered, in which he summarised present scientific knowledge about cannabis and exploded the myths and scaremongering of those who would repress it. (121)

IN 1971, the New York Academy of Sciences held an interdisciplinary conference to discuss the biological effects of marihuana and its use as a means of social control. The conference established that from a medical point of view, marihuana is less harmful than alcohol, tobacco, and a number of medicaments, such as barbiturates) and argued that "an individual should not be punished by criminal law for risking his own health."(122)

IN 1971, the US Department of Health, Education and Welfare published its first annual report to Congress, titled Marihuana and Health.(123)

IN 1972, that reputable body, the US Consumers' Union, published its extremely interesting report Licit and Illicit Drugs, edited by Edward Brecher.(124)

IN 1972, the National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse published its sensational report, Marihuana: A Signal of Misunderstanding, which was followed a year later by Drug Abuse in America: A Problem in Perspective.(125) In 1973, Professor Tod Mikuriya of the University of Berkley in California edited a unique publication titled Marihuana: Medical Papers 1839-1972, which included the most important medical works on cannabis written between 1839 and 1972.(126)

IN 1976, the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) published the findings of the international research programme it had started in 1967 and organised, funded, and overseen. The two volumes of Pharmacology of Marihuana exhaustively analyse the chemical, metabolic, cellular, immune, hormonal, genetic, reproductive, neurophysiological, and neuro-pharmacological effects of cannabis, its effects on behaviour, the consequences of long-term use, and its therapeutic properties. (127)

IN 1976, Drs Sidney Cohen and Richard Stillman published The Therapeutic Potential of Marihuana, a "hopeful prognosis for using cannabis in numerous medical applications". (128)

IN 1975-7, the results were published of long-term comparative studies of chronic users of cannabis conducted in Jamaica,(129) Costa Rica, (130) and Greece.(131)

7. The period of tolerance (1970-80)

The early 1970s saw the start of a period of tolerance of illicit substances in general and cannabis in particular. The constant publicity given to the findings of scientific research contributed to a steady strengthening of the groundswell of public opinion in favour of decriminalising cannabis and its derivatives, which was joined by many independent foundations, organisations, citizens' associations, medical societies, and prominent figures in the scientific, literary, artistic, and theatrical worlds. Increasing numbers of people gradually came to appreciate the dead-end effects and the disastrous individual and social consequences of a policy of rigorous repression of illicit substances, and this triggered developments on two levels.

On the administrative level, first of all, many governments began to ponder, while others decided to re-assess their present penal policy and adopt a medicosocial model for addressing illicit substances and their users. The Netherlands led the field in this respect, modifying its legislation on opium in 1976. On the other level, that of the active citizenry, an intellectual and political stance began to evolve, which would soon form the basis of an anti-prohibition movement in the United States that spread to the rest of the world in the 1980s.

Having played a leading part in the worldwide 'anti-drug crusade' ever since 1914, the United States was naturally the main arena for the confrontation between the supporters and the opponents of repression. By the early '70s they had grouped themselves into two clearly defined camps.

The opponents of repression, who wanted the repressive controls on illicit substances lifted, included the American Public Health Association (APHA), the American Bar Association (ABA), the Civil Liberties Union (CLU), the Consumers Union, the Medical Academy of New York, the National Organization for the Reform of Marihuana Laws (NORML), the Alliance for Cannabis Therapeutics (ACT), and thousands of academics, doctors, psychiatrists, judges, magistrates, lawyers, writers, journalists, artists, and Nobel Prize-winning scientists. In the '70s, just about all the creative people of any note in the literary, artistic, and scientific worlds were in favour of a revision of the repressive legislation against illicit substances.

Those who supported prohibition and wanted repression maintained and even intensified included the representatives of reactionary -economic and political circles, anti-drug squads, and ever-fretful parents and guardians, all together in a solid and historically unchanging alliance: the Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN), which later became the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP), and the Partnership for a Drug Free America (PDFA). They indulged in public displays of strength, supported by far-right organisations and a number of well-known personalities, including Gabriel Nahas, Lyndon LaRouche, Ross Perot, Peggy Mann, and Robert Heath.

GABRIEL NAHAS, Professor of Anaesthesiology at Columbia University and, by his own admission, committed to the war on cannabis, is the blue-eyed boy of the DEA and the professional crusaders against narcotics, who trumpet his `scientific' work on cannabis ad nauseam.

Gabriel Nahas and Lyndon LaRouche, agents of the OSS (now the CIA) participated in the cover-up of Nazi war crimes of Austrian politician Kurt Waldheim. They and others derived political leverage from it during Waldheim's rise to the United Nations Secretary General. Despite a professional scandal (for his fraudulent report of a cannabis death in Belgium, 1971) and lack of qualifications, Nahas was put in charge of all United Nations grant money for cannabis research, at the suggestion of Waldheim's daughter. His 1971 appointment to its Narcotic Control Board staff entrenched him in the narcotic control bureaucracy for a decade. (132)

At a special press conference in 1975, the University of Columbia dissociated itself from Nahas' work on cannabis, thus giving some indication of his credibility.

ROSS PEROT, a businessman from Dallas, finances a number of extreme right-wing movements and is chairman of a Texas committee against drugs. PEGGY MANN, a professional crusader, is the author of Marihuana Alen,(133) which "became the Mein Kampf of cannabis prohibition. (134) And ROBERT HEATH, Professor of Psychiatry and a CIA collaborator from 1950 onwards, has headed several of the CIA's `personality-stripping' programmes. (135)

At this point I should like to draw the reader's attention to the Randall case, which played an important part in legalising research into the therapeutic properties of marihuana and the acquisition of a new therapeutic agent. In 1972, the Sociologist ROBERT RANDALL was diagnosed with glaucoma and underwent conventional therapy with the available drugs; but the treatment was unsuccessful. In 1974, he volunteered to take part in research being undertaken by Professor Robert Hepler and his condition improved considerably. In 1975, Randall was arrested for growing cannabis and possessing marihuana for his personal use, and the conflict between scaremongering and science was raised to a judicial level. The court accepted the validity of the medical reasons why the accused needed to take cannabis and gave him the right to continue taking it on the basis of a research protocol drawn up by his doctors. And so, since 1978, the marihuana Randall needs has been supplied by the Federal Government (136)

8. Legislating for tolerance (1970-80)

All these developments helped gradually to dispel the myths and prejudices that the prohibition brigade's propaganda campaigns had implanted in people's minds, accelerated a change in popular attitudes towards cannabis, led to a revision of the sanctions imposed for possession and use of cannabis, and, finally, sparked off scientific research. This amassed an enormous volume of material, which helped to re-establish cannabis as a non-harmful euphoriant and as a useful medicament for many conditions for which there is no effective alternative treatment or, if there is, it is accompanied by serious undesirable side-effects.

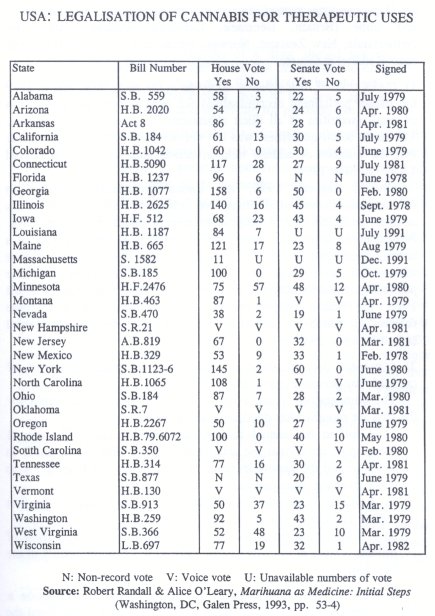

On the basis of these findings, many countries, the US Federal Government, and thirty-four American states changed their legislation on cannabis and Δ9-THC.

In 1970, the US government passed the Controlled Substances Act (its official title was the `Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act'), which made possession and use of cannabis no longer a crime but a misdemeanour. Subsequently, between 1970 and 1977:

1. ALL THE STATES considerably reduced the penalties for possession and use of cannabis.

2. ELEVEN STATES decriminalised(137) possession of small quantities of cannabis for personal use: Oregon in 1973, Alaska, Colorado, and Ohio in 1975, California, Maine, and Minnesota in 1976, Nebraska, Mississippi, North Carolina, and New York in 1977.

3. ALASKA decriminalised the possession and consumption of marihuana by adults in May 1975, by decision of its Supreme Court. The decision stated that:

The use of marihuana does not constitute a public health problem of any significant dimension. It appears that effect of marihuana on the individual are not serious enough to justify widespread concern, at least as compared with the far more dangers effects of alcohol, barbiturates, and amphetamines.(138) The Court held: thus, we conclude that citizens of the State of Alaska have a basic right to privacy in their homes under Alaska's constitution. This right to privacy would encompass the possession and ingestion of substances such as marihuana in a purely personal, non-commercial context in the home unless the state can meet its substantial burden and show that proscription of possession of marihuana in the home is supportable by achievement of a legitimate state interest.

Marihuana possession and consumption by adults in their homes was held to be a constitutionally protected activity under the Alaska state constitution's right of privacy provision in a unanimous 1975 decision by the Alaska State Supreme Court (Rauin v. State 537 P.2d 494, Alaska 1975). The court held that the state constitution's explicit privacy clause requires that the state government be prohibited from penalising adults within that state for using marihuana in private. Thus, "for nearly 16 years, adults in Alaska enjoyed the legal right to choose whether or not to use marihuana without fear of punishment by the government for doing so. But on Nov. 6, 1990, a slim majority of the voters passed ballot measure II, a statute proposed through the initiative process, which purported to restore criminal penalties for private marihuana use by adults. Whether this attempt to recriminalize marihuana use will withstand constitutional scrutiny is the subject of litigation now before the Alaska Courts." (139)

4. NEW MEXICO legalised the use of cannabis for medical purposes and between 1978 and 1992, 37 states enacted legislation recognising the valid medical uses of cannabis.(140)

Many countries moved towards decriminalising the use of cannabis and some (Britain, Denmark, Germany, Ireland, Italy, The Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Spain, and Switzerland) enacted special liberal measures.

1) ITALY revised its legislation on drugs in the early '80s, and in 1989 the Italian parliament decriminalised the procurement and possession of small quantities of all illicit substances for personal consumption. The term `small quantities' was not defined, however, with the result that the number of addicts held in prison shot up (they numbered 12,500 in May 1991).

On 13 January 1993, the Italian government decided to decriminalise the use of all drugs, and defined a `small quantity' as the amount sufficient for a dependent user's needs for three days. Possession of more than three days' doses is punishable by loss of a driving licence for one to three months for mild drugs and two to four months for hard drugs; the local prefect is empowered to make persistent offenders attend a detoxification programme. On 18 April 1993, the Italian people upheld decriminalisation in a multiple referendum which overturned the political scene that had dominated Italy ever since 1948.

2) GERMANY decriminalised the possession of small quantities of cannabis for personal consumption in 1994.

The comparative statistics released by the state of California for the first six months after decriminalisation revealed:

1) A fall in the annual increase of cannabis use. The annual increase of occasional use fell from 2.9% in 1968-75 to 2.2% in 1975-6; and the annual increase of regular use fell from 1.1 % to 0.8 % over the same period.

2) A fall in prosecutions by some 50%: from 27,000 in the first half of 1975 to 14,000 in the first half of 1976.

3) A fall in prosecution and court expenses by some 75 % : from 17 million dollars in the first half of 1975 to 4.3 million dollars in the first half of 1976.(141)

In view of the circumstances, President Jimmy Carter made a historic speech to Congress in August 1977, in which he outlined the attitude the federal authorities should henceforth adopt towards illicit substances and cannabis:

Penalties against possession of a drug should not be more damaging to an individual that the use of the drug itself, and where they are, they should be changed. Nowhere is this more clear than in the laws against possession of marihuana in private for personal use. (142)

Carter's policy was not intended to do away altogether with the folly of prohibition, but simply to rationalise the legislation covering prohibition in response to pressure both from the general public and from a sizeable proportion of the scientific world, who were publicly demonstrating their refusal to accept that the conclusions of scientific research be sacrificed on the altar of repressive hysteria.

In his efforts to reconcile the interests of the economic circles that were sustaining prohibition with the demand of millions of American citizens that an absurd policy of repression be lifted, Carter pursued an ambiguous course which ranged between the two extremes of abolishing penalties for possession and use of marihuana on the one hand and `Operation Paraquat' on the other. The latter scheme was devised in 1975 and involved spraying all cannabis and opium poppy plantations with an extremely dangerous poison, first on the territory of neighbouring countries (starting with Mexico in 1977) and then within the United States. To carry out his drug policy, President Carter appointed as his `drug tsar' (143) Peter Bourne, a psychiatrist whose controversial career was perfectly in keeping with the controversial policy he undertook to enforce.

PETER BOURNE had been sent by the Pentagon on a special mission to Vietnam in 1965 as advisor to the Green Berets (who awarded him the silver star). At the same time he was masquerading as an activist in the movement against the war. He took part in the planning of Operation Paraquat and at the same time was a fellow-traveller in the movement to revise the legislation on marihuana. He condemned barbiturates and at the same time procured them (which was the

reason for his `dethronement' in 1978). He paternalistically excoriated users of illicit substances and at the same time was an occasional user himself of marihuana and coca (as revealed by the New York Times). In 1962, he graduated from medical school in Atlanta; in 1965, he worked for the military secret services in Vietnam; in 1971, Nixon appointed him Deputy Director of the White House Drug Task Force; in 1974, as president of the one-man International Research Institute, he travelled the world offering `special advice' to anyone prepared to pay him for it. In 1976, he was crowned drug tsar, when Carter appointed him as his special advisor and Director of the White House Narcotics Bureau. In 1977, he approved the DEA's project to spray marihuana and opium poppy plantations in Mexico with lethal Paraquat. And in 1978, he was toppled from power when the Washington Post accused him of being a `user and pusher of drugs' (19 July 1978).

The Carter administration's timid attempts to rationalise the repressive legislation were seen as a terrible threat by the supporters of prohibition, who tried to pre-empt the probable developments prescribed by President Carter's speech. The elimination of Boume was a clear enough message, for, apart from being one of Carter's chief advisors, he was also his personal physician. Boume's fate was sealed in February 1978, when he conveyed the mood of the Carter administration from the national to the international level.

He addressed the United Nations Commission on Narcotic Drugs regarding United States drug policy. He did not specifically mention decriminalization, a process that some nations either had difficulty understanding or frankly opposed, but he called attention to the fact that priority of attention would be given to those drugs that caused the greatest threat to life.(144)

For the combined interests of the petrochemical, paper, pharmaceutical, alcohol, and tobacco trusts, organised crime, the prosecution authorities, and a host of people who had made their careers as professional crusaders against drugs, the danger of their being put out of commission if the Carter administration's attitude towards marihuana were internationalised was now obvious and immediate.

The DEA decided to publicise the Long case on 19 July 1978.(145) Bourne then resigned and any talk of reform in the government ceased abruptly, thus heralding the end of the `age of tolerance' and the dawn of a new phase of anti-drug hysteria, which would be dominated by an erstwhile informer yelping `Just say no', and an ex-secret service agent hollering `Zero tolerance'.

9. Back to the past: `Just say no' (1981-8)

After 1978 the political climate in the United States began to change. Energy problems and the recession were causing unrest; people were starting to turn towards the champions of neoliberalism; and developments abroad, as the balance of power the United States had engineered in various vital areas of the planet was upset (in the Middle East, for instance, with the establishment of a theocratic regime in Iran), were engendering an alarm and insecurity that made the electorate increasingly conservative in its attitudes. This found political expression in 1980, when Ronald Reagan was elected President of the United States.

RONALD REAGAN, a former film actor, an informer for the secret services, a betrayer of many of his colleagues to the Committee of Un-American Activities, and an associate of the notorious morphine-addicted Senator McCarthy and his assistant Richard Nixon during the Cold War, proved to be the right man to express the new political climate that was developing at that time in the United States.

During his first term (1981-4), Reagan tried to impress public opinion by implementing a repressive policy that was ostensibly intended to reduce the supply of illicit substances. Its key aims were:

1) To apply pressure on various foreign governments to make their drug legislation stricter.(146)

2) To increase the powers of the DEA and reduce the `legal obstacles' to its activities.

3) To extend `Operation Paraquat' by spraying cannabis and opium poppy plantations not only in neighbouring countries but within the United States too.

4) To increase the budget for equipping other countries' drug task forces.

5) To continue the financial aid programmes for replacing poppy, coca, and cannabis plantations.

6) To attempt to force scientists to destroy the protocols, documents, and findings of all the investigations into the biological effects of marihuana conducted between 1966 and 1976 with government permission and funding.

Whichever way one looks at this doomed policy, which increased rather than decreased supply, it did have one very special and historically unprecedented aspect; and that was the cold-blooded murder of marihuana users who unknowingly smoked grass that the DEA had sprayed with Paraquat. The long arm of the unscrupulous criminals masquerading as protectors of society caused and established a brand new category of deaths: those caused by marihuana with a Paraquat coating, a new lethal product launched onto the market by the DEA.

In 1981, on the recommendations of George Bush and Nancy Reagan, President Reagan appointed Carlton Turner Director of the White House Narcotics Bureau. The standard of Ronald and Nancy's anti-drug policy is clearly reflected in the curriculum vitae of the man they chose as their `drug tsar'.

CARLTON TURNER was a careerist with a `business mind'. In 1978 he tried to market a fake Paraquat test. In 1981, Reagan appointed him Director of the White House Narcotics Bureau, and from then until 1986 he relentlessly targeted jazz and rock music and made unsuccessful efforts to ban radio and TV networks from broadcasting it, obsessed as he was by the idea that it was the main reason behind the `drug problem'. On 25 April 1985, he demanded the death penalty for `drug traffickers'. On 27 October 1986, Newsweek mounted an acrimonious attack on him, as a result of which he was forced to resign on 6 December 1986. Having taken advantage of every microphone that was offered to him to declaim that the use of marihuana led to homosexuality, depressed the immune system, and caused AIDS, Turner then worked with Robert DuPont and the formerDirector of the NIDA, Peter Bensinger, to market a test for detecting cannabis in urine.

Between 1981 and 1983, the DEA sprayed marihuana plantations in Georgia, Kentucky, and Tennessee with Paraquat, and this led to the `inexplicable' deaths of many users. In 1983, in a vain attempt to defuse public outrage when the truth came out and to play down the government's responsibility, Turner appeared on national television and, having first contested that the deaths had in fact been caused by Paraquat (which had been proven by state organisations and state laboratories), he then proceeded to justify the DEA's activities by claiming that if the victims had indeed been killed by Paraquat they had only themselves to blame for smoking a prohibited substance in the first place.

In 1983, the US government was forced publicly to condemn the use of Paraquat for spraying plantations and to announce that Paraquat would henceforth be prohibited for that purpose. The trouble was that the ban was never enforced, and in 1993 government planes were still shedding that dangerous poison over vast areas of the United States and certain neighbouring countries. (147)

In September 1983, the President's office wrote to all the universities in an effort to sound out their intentions and likely reactions to the proposed destruction of the data from all the cannabis research conducted between 1966 and 1976, including the synopses in the university libraries. (148) It was all research that had been undertaken with government permission and government funding. All the documents were public records, and their destruction would constitute a violation of the restrictions the Constitution laid upon the executive powers. The reasoning behind these machinations, so reminiscent of the practices of Nazi and Communist totalitarianism, is obvious.

Between 1966 and 1987, 10,000 investigations into cannabis had been carried out, and only twelve of them had produced negative conclusions about the `forbidden plant'. The findings of those twelve had never been corroborated when other researchers repeated them. The whole of this vast mass of research material proved that the state's policy of repression of cannabis was totally at odds with the scientific facts and that the prohibition of cannabis was based not on scientific criteria but on self-interested financial and political ones. Consequently, if it were to maintain the policy of repression and return to the good old days of the witch-hunt, as it wanted to do, the President's office needed to get rid of all those bothersome scientific data that gave the lie to everything it said.

During Reagan's second term (1985-8), the resounding failure of the presidential policy to reduce the supply of illicit substances could no longer be ignored and was being criticised by most of the American press. So Reagan's anti-drug squad dropped it and adopted another, in an attempt this time to target demand for the said substances. All that this meant was that persecution now focused on use and users, rather than on dealing and dealers.

So for the first time in human history an `international crusade against drugs' was organised, the publicly proclaimed target of which was not the dealers but the users of illicit, substances. Its revealing slogan, `Just say no', was, of course, addressed exclusively to users. `Just say no': in other words, since we can't get at the supply, i.e. the dealers, let's wipe out the demand, i.e. the users.

10. Persecution frenzy: `Zero tolerance' (1989-92)

In 1989, George Bush took over the presidency from Reagan. He appointed William Bennett Director of the White House Drug Bureau and put him in charge of the presidential 'anti-drug' policy, chiefly within the United States, and Melvin Levitski Undersecretary of State for drugs, who was responsible for implementing the policy abroad.

WILLIAM BENNETT, addicted to alcohol (daily `social' use) and nicotine and a rabid opponent of marihuana, had no particular knowledge of drugs; but he was admirably suited to the organising of all the presidency's dirty work in relation to them. During his reign, he bombarded public opinion with 'anti-drug' clichés and, needless to say, he was zealously in favour of the death penalty for dealers. `I have no moral problem with hanging dealers,' he said. `My only problem is legal.' MELVIN LEVITSKI was closely involved with the secret services and the DEA and was thus in a position to apply pressure upon such international organisations as the UN and the EC, and particularly upon the governments of various countries, in his efforts to persuade them to adopt George Bush's `Zero tolerance' policy.

GEORGE BUSH, addicted to benzodiazepine (Halcion),(149) was an agent and later Director of the CIA (1975-7), after which he was appointed a director of the Eli Lilly pharmaceutical company (1977-9) by the father of his future vice-president Dan Quayle, whose family controls the company. The Bushes have close links with the pharmaceutical industry and own a significant number of shares in Eli Lilly, Abbott, Bristol, and Pfizer. As director of Eli Lilly & Co., G. Bush "owned $145,000 worth of stock in the drug company. He lied on April 14, 1982, that he had sold his 1500 shares in 1978. It was, in fact, still his single most valuable stock holding."(150)

From 1981 to 1988, Bush was director of Reagan's Drug Task Forces and at the same time Vice-President of the United States. In this dual capacity he was implicated in cocaine trafficking,(151) and did his best to promote Eli Lilly's interests in South America, particularly in Puerto Rico, by no end of unfair practices, for which he was called sharply to heel by the US Supreme Court in 1982.(152) As President (1989-92), Bush continued Reagan's 'six-point' drug policy, merely changing the slogan from `Just say no' to `Zero tolerance' (of users).

Within the United States, he stepped up the repressive measures, armoured the forces of repression both financially and legislatively, and doubled the prison population. Between 1988 and 1991, the budget for the forces of repression was increased by $4,000 and their unconstitutional (and therefore illegal) activities were 'legalised' by a string of presidential regulations. Arrests for mere possession of marihuana went up from 324,000 in 1988 to 390,000 in 1990.(153) In this way Bush kept one part of the twofold promise he had given to the American people when he announced his drug policy on 5 September 1989: that he would solve the drug problem by sending all dealers to jail. During his presidency, over 500,000 users were arrested and imprisoned annually (400,000 were users of cannabis), and the only result was that the drug problem got worse and the prison population doubled.

Outside the United States, Bush used the `war on drugs' as a foreign-policy tool, and in the name of protecting humankind from the danger of drugs he `legalised' the drug trade as a source of revenue that could be used to overthrow regimes that were in Washington's bad books and to further the United States' right to invade other countries' territory.

With full presidential cover, top-ranking state officials supplied the Contras in Nicaragua with laundered money to help them in their efforts to overthrow the Sandinista regime. On the President's orders, the US army invaded Panama, and toppled and arrested the dictator Manuel Noriega, a former CIA agent and high-ranking member of the international consortium of organised crime that controls traffic in illicit substances. The link between Iran and Nicaragua, Granada and Panama clearly reveals the real purposes behind the unified policy of `arms for drugs' implemented by Reagan and Bush, the undisputed leaders of the `world crusade against drugs'. Particularly in view of the fact that all the protagonists in the policy (those eminent crusaders Oliver North, John Hull, John Poindexter, General Secord, Lewis Tambs, and many other members of the American secret services) are now wanted by the Costa Rican authorities because of their extensive drug trafficking in that country.(154)

In 1991, the United Nations transferred synthetic Δ9-THC from Schedule I to Schedule II of controlled mind-affecting substances, but cannabis stayed on Schedule 1, after intensive lobbying by Melvin Levitski on Bush's orders.(155)

Proffering the excuse thatΔ9-THC `has proven medical benefits and is not widely used outside legitimate medical channels', whereas cannabis `is used illegally by millions of people worldwide', the US government placed the control of the profits from the production and supply of syntheticΔ9-THC securely in the hands of the synthetic pharmaceutical industry (which would never have been possible with natural cannabis).(156)One of the companies that stood to gain considerably from the arrangement was Eli Lilly.

Synthetic Δ9-THC was put on Schedule II of controlled mind-affecting substances because, like all synthetic pharmaceuticals (most of which are extremely toxic, hazardous rubbish), for the last seventeen years it has been the exclusive monopoly of the pharmaceutical companies that produce it and make an enormous profit from it. Cannabis stayed on Schedule I because it is a natural product and as such its production and supply cannot be monopolised by the pharmaceutical companies.

In 1988, after two years of hearings on marihuana's therapeutic benefits `for individuals undergoing cancer chemotherapy and for multiple sclerosis patients', the DEA's Chief Administrative Law Judge, Francis L. Young, ruled that current federal policies prohibiting marihuana's medical use are `unreasonable, arbitrary and capricious', and urged the DEA to reclassify marihuana to reflect its medical uses.

The evidence in this record clearly shows that marihuana has been accepted as capable of relieving the distress of a great number of very ill people, and doing so with safety under medical supervision. It would be unreasonable, arbitrary, and capricious for the DEA to continue to stand between those sufferers and the benefit of this ,substance in light of the evidence in this (157)

But shortly after George Bush took office in 1989, the head of the DEA, John Lawn, rejected the 1988 recommendation of his own agency's top administrative law judge, and marihuana still remains on Schedule I, proving that the marihuana issue is primarily a political issue rather than a medical one.

The criticism the American press unleashed against the deplorable farce of Reagan's and Bush's `drug crusades' focused on their resounding failure, their immensely destructive side-effects on American society, and their enormous cost, which was overwhelming even for a wealthy nation like the United States.

The reaction of American society to its two presidents' `drug war' games is accurately reflected in the titles of some of the articles published in the American press between 1985 and 1990:

`Legalize Dope' William F. Buckley (Washington Post, 1 January, 1985)

'Let's Quit the Drug War' David Boaz (New York Times, 17 March, 1988)

`Once Again, a Drug-War Panic' D. Bandow (Chicago Tribune, 22 March, 1989)

`Why Not Try Decriminalization?' Richard Cohen (Washington Post, 12 April, 1988)

'We're Losing the Drug War Hodding Carter III (Wall Street Journal, 13 Because Prohibition Never Works' July, 1989)

`Legalizing Drugs-Step No. 1' Kiddare Clarke (New York Times, 26 August,

1989)

`A Worthless Crusade' Rufus King (Newsweek, 1 January, 1990)

77 Such as the cola nut, which was discovered in western Africa and taken to America, where it was used as an ingredient in cola drinks; and the plant ilex from Brazil and other countries, which was passed on by the northern Native Americans to the White colonists, who made from it a drink they called `black drink' or 'dahoon'.

78 In America, morphine salts were first produced and sold in 1832 by the Philadelphia firm of Rosengarten & Co. (from which later emerged the well-known pharmaceutical company Merck, Sharp, & Dohme).

79 T. Szasz, Ceremonial Chemistry (1975), p.75.

80 K. Grivas, Oppositional Psychiatry (1989; in Greek), p.16.

81 The use of the 'war on drugs' as a tool of domestic and foreign policy is analysed in greater detail in K. Grivas, Prohibition: A Tool of Domestic and Foreign Policy (at press)

82 Storeyville is the birthplace of Buddy Bohler, Buck Johnson, Louis Armstrong, and many other outstanding jazz musicians.

83 J. Herer, The Emperor Wears No Clothes (1992), p.67.

84 J. Herer, The Emperor Wears No Clothes (1992), p.67.

86 US Department of Agriculture, Bulletin No 404, Hemp Hurds as Paper-making Material (Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 14 October 1916).

87 C. Carroll, Drugs in Modern Society (1993), p.327.

88 D. Musto, The American Disease: Origins of Narcotic Control (1987), pp. 8, 19, 24-53.

89 D. Musto, The American Disease (1987), p.25

90 Gabriel Nahas, one of the leading lights of the postwar anti-drug campaigns, effectively concedes as much when he writes, with reference to the Conference, that `cannabis was put on the forbidden list, not because of medical reasons, but because of social ones' G. Nahas, Keep off the Grass (1990), p.35.

91 Which became the DEA in 1971.

92 A. Lindesmith, `The Addict and the Law', in D. Solomon, ed., The Marihuana apers (1966), p.24.

93 In 1937, the Mellon Bank in Pittsburgh was one of the six largest banks in the USA.

94 In 1934, Senator Jerome Guffey denounced Anslinger as a racist from the Congress rostrum.

95 The records and files of the former FBN are kept in the DEA Library in Washington.

97 The banning of cannabis in 1937 had been foretold to a great extent between 1926 and 1936, when Wallace Carothers, one of the leading chemists in the DuPont laboratories, managed to make nylon out of petrochemical materials.

98 Lammot DuPont, in Popular Mechanics, June 1938, p.805. Quoted in Herer (1992), p.23.

99 Hearst Paper Manufacturing Division.

102 US Department of Agriculture, Ag. Extension Leaflet 25, March 1943.

104 L. Grinspoon, Marihuana Reconsidered (1977), p.339.

105 G. Nahas, Keep of the Grass (1990), p.123.

106 J. Herer, The Emperor Wears No Clothes (1992), p.28.

107 US Congress, House Ways and Means Committee, Taxation of Marihuana, Hearings on H.R. 6385, 75th Cong., 1st sess., April 27-30 and May 4, 1937, p.24. quoted in J. Himmelstein, The Strange Career of Marihuana (1983), p.62.

108 L. Grinspoon, Marihuana Reconsidered (1977), pp.218-30.

109 USA (1936). The official Pharmacopoeia continued to list cannabis as a harmless medicament until 1942, five whole years after the Marihuana Tax Act came into force. It was removed in 1942 under pressure from Harry Anslinger and the FBN.

110 R. Adams and B. Baker, `The Structure of Cannabinol VII: A Method of a Tetrahydrocannabinol which Possesses Marihuana Activity', Jour. Amer. Chem. Soc., 62 (1940), 2405-8.

111 New York Mayor's Committee Report, The Marihuana Problem in the City of New York (Lancaster, N.Y., 1944). Reprinted by Scarecrow Reprint, Metuchen NJ., 1973.

112 L. Grinspoon, Marihuana Reconsidered (1977), p.309.

113 Editorial, 'Marihuana Problems', JAMA, 127 (1945), 1129.

114 D. Musto, The American Disease (1987), p.230.

115 T. Szasz, The Therapeutic State (1984), p.306.

116 L. Grinspoon, Marihuana Reconsidered (1977), p.3.

118 Advisory Committee on Drug Dependence Report: Cannabis. Wootton Committee Reeport (1968).

119 R. DuPont, in Braude and Szara, eds., Pharmacology of Marihuana (1976), p.4.

120 Commission of Inquiry into Non-Medical Use of Drugs (1970), Interim Report: LeDain Report, 1970.

121 L. Grinspoon, Marihuana Reconsidered (1977).

123 US Department of Health, Marihuana and Health: First Annual Report to the US Congress (1971).

124 E. Brecher, Licit and Illicit Drugs (1972).

126 T. Mikuriya, Marihuana: Medical Papers, 1839-1972 (1973)

127 M. Braude and S. Szara, eds., Pharmacology of Marihuana, A Monograph of the NIDA (1976).

128 S. Cohen and R. Stillman, eds., The Therapeutic Potential of Marihuana (1976).

129 V. Rubin and L. Commoa, Ganja in Jamaica: A Medical Anthropological Study of Chronic Marihuana Use (1975). Also available as Jamaican Studies, 1968-1974 (1975).

130 P Satz, J. Fletcher and L. Sutker, in Ann. N.Y. Academy of Sciences, 282 (1976), 266-306.

132 C. Conrad, Hemp: Lifeline to the Future (1993), p.229.

133 P Mann, Marihuana Alert (1985).

134 C. Conrad, Hemp: Lifeline to the Future (1993), p.230.

135 K. Grivas, Oppositional Psychiatry (1989; in Greek), p.86.