CHAPTER 7 A CRITIQUE OF CURRENT VIEWS OF ADDICTION

| Books - Addiction and Opiates |

Drug Abuse

PART I The Nature of the Opiate Habit

CHAPTER 7 A CRITIQUE OFCURRENT VIEWS OF ADDICTION

The views of addiction most commonly expressed in both the popular and the scientific literature have not changed significantly for many decades. The main substantial change has been in the vocabularies employed to express them. This is made evident by listing terms that have been used to describe addicts or types of addicts, usually with the assumptions that what is being described is an addiction-prone personality type and that the named attribute has etiological significance. All of the terms that follow are taken from only two studies: that of Terry and Pellens (1) in 1928, which presents older terms taken in some cases from literature of the nineteenth century, and that of Ausubel, (2) published thirty years later: "alienated," "frustrated," "passive psychopath," "aggressive psychopath," "emotionally unstable," "nomadic," "inebriate," "narcissistic," "dependent," "sociopath ... .. hedonistic," "childlike," "paranoid," "rebellious," "hostile," "infantile," "neurotic," 11 over-attached to the mother," "retreatist," "cyclothymic ... .. constitutionally immoral," "hysterical," "neurasthenic," "hereditarily neuropathic ... .. weak character and will," "lack of moral sense," self-indulgent," "introspective," "extraverted," "self-conscious," motivational immaturity," "pseudopsychopathic delinquent," and finally, "essentially normal."

Views or theories of addiction advanced by different writers can, as a rule, be reliably predicted from knowledge of the investigator's professional and intellectual training and commitments. Orthodox Freudians find, in addiction behavior, a confirmation of Freud's ideas; Adlerians propound Adlerian theories; behavioristic psychologists who are followers of Skinner find that drug addiction fits neatly into the framework of operant conditioning. sociologists who are followers of Merton emphasize alienation, anomie, and the double-failure hypothesis; statisticians tend to -e the methodological blunders, connected with sampling e of controls, that are committed by the nonstatisticians; trained researchers suggest biological theories and by the subjectivism and lack of precision of behavioral gical studies. is is true, it implies that theories of addiction are 'ling other than the facts. If the data serve only existing ideological positions of the investigate controversies are likely to be noisy and futile conducive to the formulation and progressive thereof theory which is characteristic of genuine science on the assumption that the controversy between competing positions stems in large part from the fact that different investigators proceed from different and usually unstated methodological presuppositions, I have tried to state my own fairly explicitly and fully in the foregoing chapters. The comments in this chapter on views which I do not share and which seem mistaken to me are implied by my own methodological assumptions. Thus, I must state that most of the views examined in this chapter are not genuine theories at all from my standpoint, either because they do not purport to be generally applicable to all opiate-type addiction or because they are so formulated that no conceivable evidence to negate them is possible or conceivable. Persons who think of scientific theories in other terms than these will naturally not agree with my evaluations. When a theorist or a critic makes his assumptions explicit, those who disagree are in the position of knowing whether they should discuss the evidence or concern themselves rather with questions of scientific method and logical inference.

Psychopathy and Addiction

Thirty years ago, in a discussion of drug addiction, E. W. Adams, a well known British writer on this subject, stated:

It is almost universally agreed now, that running beneath all other causes is an inherent mental or nervous instability of a greater or less degree. That statement may be said to rest upon evidence as convincing as that upon which most of the canons of medicine are based. Addiction can, as will later be seen, be brought about in persons mentally normal Jo all appearances, if deliberate attempts are made with this object or if their medical advisers unwisely subject them to unduly prolonged narcotic treatment, but such persons will not become addicts of their own accord. Ordinarily, then, addiction is a sign of a mental makeup which is not entirely normal.... We shall not go wrong, then, in accepting as a fact the existence of this psychopathic basis in the large majority of the victims of drug addiction. (3)

Numerous other authorities who agree with this conclusion are cited by Adams, and essentially the same views have been expressed by countless writers since that time.

It is at once evident from Adams' statement that it does not qualify as a scientific general theory of addiction because it claims only that mostaddicts who become addicted by voluntarily taking drugs are abnormal in some way and implies that this abnormality occurs more often among addicts than among non addicts. His statement suggests that the above conclusions may be reversed in the case of those persons who become addicted in medical practice without using the drug voluntarily. While he asserts the existence of a psychopathic basis for most voluntary addiction, Adams does not stop to consider whether even this weak conclusion is generally or universally valid. For example, in Eastern countries where folk beliefs bold that opium is an effective remedy for widespread tropical diseases, for sexual impotence, and other complaints and ailments, would voluntary use of opium under such circumstances have the same psychopathic basis? Does such a psychopathic basis exist when the use of the drug is a status symbol, as it has been among upper-class Chinese? Would this idea apply to communities in China and other Eastern countries where it has been reported that it was the custom of virtually all adult males to use opium?

The view expressed by Adams is still widely accepted among students of addiction despite its obvious deficiencies and the wide range of disagreement as to bow the alleged psychopathic predisposition or addiction-prone personality is to be described. Some writers in Adams' time and earlier sought to extend the conclusion to all addicts just as contemporary students occasionally do.

This position is, in my opinion, mainly a reflection of a popular conception which long antedates it, that persons with bad compulsive habits are afflicted with "weak wills." A narcotic agent whom I asked why addicts used drugs replied that it was because 11 they are weaklings'' The prevalence of the popular view and the scientific view with which it is in essential agreement is based primarily on frequency of repetition rather than on evidence. Even if it were to be unequivocally confirmed that most addicts are in fact not psychologically normal, little would be gained, since the problem of explaining the mechanisms of addiction would still remain and it would still be necessary to account for the minority, however small, of addicts to whom the description did not apply.

Two of the older studies may be taken as prototypes of this approach. Both were published by competent investigators of excellent standing in their professions, Dr. Lawrence Kolb and Dr. Charles Schultz. As is characteristic of studies in this tradition, both present a classification of addicts as the main grounds for their conclusions. In a study by Kolb, 225 addicts were classified in the following categories: "Normals who are accidentally or necessarily addicted in medical practice ( 14 per cent). Care free individuals, devoted to pleasure, seeking new sensations (38 per cent). Definite neuroses ( 13.5 per cent). Habitual criminalsalways psychopathic ( 13 per cent). Inebriates (21.5 per cent) . (4) Kolb states that all these addicts became addicted "because of the pleasurable mental satisfaction that the first few doses of the narcotic gave them. The degree of inflation varies in direct proportion to the degree of pathology. It occurred only slightly or not at all in those considered nervously normal, but was very striking in some of the extreme psychopaths." (5)

Concerning the habitual criminal, Kolb asserts: "Habitual criminals are psychopaths, and psychopaths are abnormal individuals who, because of their abnormality, are especially liable to become addicts."(6) He concludes:

The instability of the various abnormal cases expressed itself in some form of social or Psychical reaction that marked them off as different from the average stable individual. They were not necessarily invalids or vicious; some of them were useful citizens and remained so; others were so abnormal as to have been social problems before their addiction, or the use of narcotics with its attendant social and physical difficulties, had seriously reduced their efficiency.

Frank cases of hysteria and psychasthenia were less common than cases that showed biased personality of one kind or another. Psychopathic characters, periodic inebriates, extremely temperamental individuals, and persons who had been problem children were more common than cases with phobias, fits, or pathological fears. A common type among these cases is a psychopath who, with his special deviation of personality, is, in the language of the street, an individual who knows it all and does not care....

The psychopath, the inebriate, the psychoneurotic, and the temperamental individuals who fall easy victims to narcotics have this in common: they are struggling with a sense of inadequacy, imagined or real, or with unconscious pathological strivings that narcotics temporarily remove; and the open make-up that so many of them show is not a normal expression of men at ease with the world, but a mechanism of inferiors who are striving to appear like normal men. (7)

In another study of 119 persons who became addicted in medical practice, Kolb rated only 67 per cent as psychopathic, (8) while in a third study he found that go per cent Of 210 cases were psychopathic prior to addiction. (9) He summarizes his viewpoint as follows:

It has long been recognized by students of the subject that the addict is generally abnormal from the nervous standpoint before he acquires the habit while some, like Block, assert that normal persons never become habitues. It is probable that Block does not class as habitues persons who, because of certain painful conditions, are necessarily addicted in the treatment of them. If this assertion allows for this exception and is limited in application to countries which like the United States have laws that protect people from the consequences of their own ignorance, its accuracy is supported by my own findings. Ninety-one per cent of this group and eighty-six per cent of a group reported elsewhere by me deviated from the normal in their personalities before they became addicted....

The unstable individuals who constitute the vast majority of addicts in the United States may be divided into two general classes: Those having an inebriate type of personality, and those afflicted with other forms of nervous instability. The various types find relief in narcotics. The mechanism by which this is brought about differs in some respects in the different types but the motive that prompts them to take narcotics is in all cases essentially the same. The neurotic and the psychopath receive from narcotics a pleasurable sense of relief from the realities of life that normal persons do not receive because life is no special burden to them. The first few doses, especially if larger than the average medicinal doses, may cause nausea and other symptoms of discomfort, but in the unstable there is also produced a feeling of peace and calm to which they are not accustomed and which, because of its contrast with their usual restless and dissatisfied state of mind, is interpreted as pleasure.(10)

Schultz classified 318 cases of addiction in the following manner:

Unclassified, 42 patients (13.2 per cent); i.e., in 13.2 per cent of the patients treated, little or no evidence could be elicited of psychopathic personality other than the drug addictionper se. These cases gave the impression of having possessed and still retaining normal personalities.

Inadequate personalities,' 96 patients (30 per cent). While the majority in this group were probably psychopathic types who had been the shiftless black sheep and ne'er-do-wells of their families before using drugs and whose failings may have been accentuated as a result of the addiction, there were some who appeared to have been fairly normal individuals before using drugs, but who went to seed afterwards, from what information was available.

Emotional instability, 65 patients (20 per cent). Here there is a question, in some cases, as to whether the instability was present before or came as the result of the addiction. Undoubtedly, the majority were unstable before using drugs....

There are some types who from their previous histories appear to have been more stable before using narcotics, and in whom the instability was secondary to the use of drugs. (In all observations carried out on these drug addicts, the emotional instability was the most striking feature.)...

The following groups appear to have been basically psychopathic. Criminalism, 41 patients (13 per cent). The dominant feature here is seen to be profound egotism combined with complete indifference in regard to ethical issues. The exclusive aim of such an individual is his own pleasure or his own interest. He has neither sentiment of honor nor respect for the truth. His unique pre-occupation is toescape conviction and punishment. . . .

Paranoid personality, 29 patients (9 per cent). In this type we find conceit and suspicion, and a stubborn adherence to a fixed idea; contempt for the opinions of others, argumentativeness, and a tendency to develop persecutory trends.

Nomadism, 26 patients (8 per cent). The nomadic or wandering tendency is present in most of us to some degree and, as all know, is in certain races so pronounced as to govern their mode of existence and social organization. . . .

Sexual psychopathy, 18 patients (6 per cent), homosexuality. These patients all showed the stigmata and reactions which were characteristic. In addition, many patients showed tendencies to be masochistic; e.g., pricking themselves with pins and needles during treatment or asking for "sterile hypos" after they were off treatment to get a "kick" out of it. This they termed "needlemania" [The followers of Watson and Pavlov might call this a conditioned reflex.]

Thus if we exclude all those in the unclassified and inadequate personality groups, we still have about 56 per cent who appear to have been constitutionally psychopathic.

However, most of those grouped as inadequate personality were probably also basically psychopathic, so that we have between 56 per cent and 87 per cent of the patients who may well have been psychopathic before acquiring the state of drug addiction.(11)

Since the attributes which are said to characterize the various types of addicts in these studies also exist among non-addicts, before one could say with assurance that they were more frequent among drug users it would be necessary to compare addicts with non-addicts from the same social strata, residential and family backgrounds, income level, ethnic background, and so on. However, no control groups were utilized in these two studies.

A more recent investigation by Gerard and Kornetsky, (12) in which a controlled comparison is made, is often cited to support the current versions of the position under discussion. Gerard and Kornetsky used a randomly selected group Of 32 adolescent addicts who were federal probationers or volunteer patients admitted consecutively to the Lexington Public Health Service Hospital. The controls consisted Of 23 non-addicts who were acquaintances or friends of known addicts, who were of the same age, ethnic and educational background, who lived in high drug-use census tracts in New York City, and who bad "no probationary or institutional record." The search for control subjects began with91 prospects, of whom all but 23 had to be eliminated for a variety of reasons.

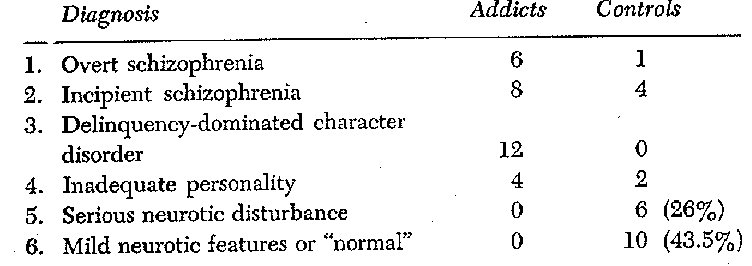

The findings of the study were based mainly upon results obtained from administering the Rorschach and Human Figure Drawings tests, and from a psychiatric interview with each of the subjects in both groups. Evidently because some addict subjects were lost before the study was completed, the authors summarized their psychiatric diagnoses with respect to 30 addicts and the23 controls as follows.(13)

These results are sharply at variance with those reported by Kolb and Schultz and many other writers in a number of interesting respects. Schizophrenia, for example, which Gerard and Kornetsky report in overt or incipient form in almost half of their addicts, is not mentioned at all by Kolb and Schultz. The latter writers, on the other band, mention definite neuroses or neurotictype ailments which Gerard and Kornetsky find only in the controls. All of these studies are alike in at least one respect, namely, that the categories containing the largest number of cases are invariably especially nebulous and poorly defined. In Kolb's studies about 60 per cent of the addicts are characterized as carefree individuals devoted to pleasure or as inebriates; Schultz describes 50 per cent of his cases as inadequate personalities or emotionally unstable; Gerard and Kornetsky find that most of their addicts who did not fit under the schizophrenia labels bad delinquencydominated character disorders while no controls did. Since the controls in the latter study were selected on the basis of having no probationary or institutional record, this particular difference was guaranteed in advance by the design of the study and is of no significance. The manner in which the controls were selected suggests that the comparison, besides being one of addicts with non-addicts, was also to a considerable extent a comparison of delinquents and non-delinquents in high delinquency areas.

Gerard and Kornetsky themselves indicate that the size of their sample was inadequate for secure conclusions to be drawn from it. Another serious problem is involved in their interpretations of the Rorschach results, which -they found differentiated significantly between addicts and controls and buttressed their conclusions. In a footnote, the authors note that a clinical psychologist who made a blind rating of the Rorschach protocols found no statistically significant differences whatever between the addicts and the controls. (14) This makes one wonder what would have happened if the

psychiatric interviews bad also been blind, that is, without the interviewer's knowing which subjects were addicted and which not. As Clausen has suggested, it is virtually impossible to interview an addict without tending to attribute to him the personality traits which ones entire training and ideological commitments indicate must be there. (15)

Another 'classification of addicts has been developed by Ausube], who regards his scheme as superior to "the widely used Kolb classification."(16); According to Ausubel, there are three basic categories of opiate addiction: (1) "primary addiction in which opiates have specific adjustive value for particular personality defects"; (2) symptomatic addiction in which the use of the drug is "only an incidental symptom of behavior disorder and has noadjustive value"; and (3) reactive addiction "in which drug useis a transitory developmental phenomenon in essentially normalindividuals influenced by distorted peer groups.(17) The first category of primary addiction includes two subtypes: the inadequatepersonality and drug use in connection with anxiety and reactivedepression states. Symptomatic addiction occurs' mainly in "aggressive antisocial psychopaths," or criminals, for whom the drughas no particular adjustive value but is merely incidental in acriminal career. Reactive addiction, according to Ausubel, is essentially an adolescent phenomenon involving mainly "essentially normal boys and girls" for whom the use of drugs "is largely anon-specific aggressive response to the prolonged status deprivation to which adolescents are subjected in our society."(18) Thiskind of addiction, he says, is usually transitory and self-limiting,with no serious or lasting consequences.

The above description of adolescent addiction is in sharp conflict with that of Gerard and Kornetsky, and the assertion that youthful addiction is a relatively trivial matter, easily overcome and with few serious long-range consequences is, simply not true. Speaking of Kolb's inclusion of persons who are accidentally addicted in medical practice, Ausubel dismisses them with the assertion that they are "rare and are not true addicts since their addiction is based chiefly on physical dependence and has little adjustive value in a psychological sense."(19) In support of his classificatory scheme he advances the astonishing argument that parents and teachers who think that anyone can become addicted will be relieved to learn that only those with "very special kinds of personality defects can become truly addicted to drugs.(20)

It is evident that the promulgation of classificatory schemes such as those that have been described has not contributed significantly to the development of theory. While almost all of them recognize the existence of addicts without psychiatric problems and personality defects apart from addiction itself, none offers a rational way of accounting for this. If addiction is contracted because of personality defects one may ask why normal persons also become addicted. If the answer is like that of Ausubel, that is, such persons are addicted largely because of the withdrawal symptoms, why should not the same symptoms be sufficient to addict abnormal persons?

Almost all of the writers who, like Ausubel, Kolb, Schultz, and Gerard and Kornetsky, have adopted classificatory schemes in support of the view that addiction is produced by psychiatric or personality problems, have concerned themselves exclusively with American addicts, and have contented themselves by applying their conclusions to "most," "the great majority," or the "bulk" of twentieth century American heroin addicts. Kolb, however, intimated that his conclusions might not be applicable in other countries where laws do not protect individuals against the consequences of their own ignorance as they are presumed to do in the United States. As a matter of fact, of course, which kinds of persons become addicted is a matter that is influenced by patterns of availability, by control policies by social custom, and by many other factors. The pattern of recruitment in the United States of the twentieth century is vastly different from that of the nineteenth, and both differ drastically from some of those found in European and especially in Asiatic countries.

In their superb survey of the literature of addiction up to 1928, Terry and Pellens evaluated the classificatory schemes that bad been proposed, in words that are as relevant today as when they were written:

In the foregoing, one is struck with the contradictions apparent in the widely varying views expressed as to the types of individuals predominating among chronic opium users. Unless we bear in mind, along with other coexisting factors which will be discussed below, the fact that for the most part each writer was influenced by impressions received from observations on selected cases, we may become confused by the picture presented. For example, terms such as "constitutionally inferior," "degenerate," "vicious," "highly intellectual," "akin to genius," "of the upper social strata," "of the most depraved type, 11 "potential criminals," etc., etc., commonly have been used to indicate type characteristics. All too often the proponent for one type or another loses sight of the fact that his experience has been limited because of certain influencing factors to a selected group.

It is obvious, therefore, that generalizations from such selected and hence quite atypical groups are valueless and prejudicial to a true conception of the real nature of the problem as a whole....

In addition to the foregoing possible misinterpretations oil the part of the writers quoted, is it not possible that where individual writers have accorded to certain types a tendency to the use of this drug, effect has been mistaken for cause? Have not these patients, possibly as a result of the situation in which they find themselves-the toxic effect of the drug, disturbed metabolism, fear of discovery and realization that unaided they cannot regain their health presented temporarily characteristics that were not constitutional with them? In spite of frequently repeated statements that the use of opium and its derivatives causes mental and ethical deterioration in all cases, we are inclined to believe that this alleged effect has not been established. The evidence submitted in support of such statements, in practically every instance coming under our notice, has been secured after the development of the addiction and was not based on a knowledge of the individual's condition prior to his addiction. In other words, the pre-addict has not been studied, and traits of character, ethical standards, and intellectual capacities based on post hocfindings may or may not have a propter hoc significance and effects attributable to the influence of the drug quite possibly may be evidence-as also may the taking of the drug-of pre-existing constitutional tendencies. It may be said with equal truth in considering the claims of those who state that certain types of individuals comprise the bulk of chronic opium users, that for one reason or another in the writings of many, 11 types" as generally understood are not considered as such until extraneous circumstances, possibly even the use of the drug itself, have altered the individual or group in question. In other words, what might be called the original type has come to be something else or attributes or factors not inherent in type delineation have been introduced as type-descriptive. Wherever the truth may lie the evidence submitted in support of the statements appearing in this chapter dealing with type predisposition and with the effect of opium use on mental and ethical characteristics is, in our opinion, insufficient to warrant the opinions expressed. . . . Unfortunately, in an attempt to present a comprehensive picture of the sociologic, constitutional, and other types of individuals involved in chronic opium intoxication, we are handicapped by the fact that there are available few valuable data, but rather in their place we find categoric statements without any presentation of the evidence upon which they are based. For the most part, we have found as data brief series of cases which by reason of the factors determining their selection may not be considered typical of the opium-using population as a whole.

In general, however, it would appear from the data submitted that this condition is not restricted to any social, economic, mental or other group; that there is no type which may be called the habitual user of opium, but that all types are actually or potentially users.(21)

It is difficult to discover in what exact sense the term "normal" is defined by Kolb and others, who take the position that addiction can be explained by the preexisting abnormality of the person who becomes an addict. It is clear, however, that the term is not used in the sense of "average." Kolb, Ausubel, and Schultz admit that normal persons, as they define them, do become addicts, but the implication of their theory is that they should not that they should show immunity. Apparently some practicing physicians have been more consistent in this matter. Ernst Meyer, a writer who held to the psychopathic theory, tells of cases known to him in which physicians. ordered morphine for repeated use with the explanation that there was no danger because of the absence of psychopathic predisposition. Meyer solemnly warns against this practice: "Care in the use of narcotics should still be maintained in spite of the theory that a psychopathic constitution is a necessary basis for the development of a chronic abuse of the drug. " (22)

Since all of the so-called character and personality defects which are said to lead to addiction also exist in the general population and are often found in the addict only after he has become addicted, the view being considered appears as an ex post facto explanation without practical or predictive value for the physician. Indeed, as Meyer indicated, it is a dangerous doctrine for physicians or anyone else to accept, if its logical implication, that there are some types of persons who are immune to addiction because of normal personality makeup, is accepted and acted upon.

Joel and Frankel have sharply criticized this view of addiction as a consequence of psychopathy in terms which are directly applicable to current positions like those of Ausubel, Gerard, and Kornetsky:

This conception is wrong in all its details and has dubious consequences. Even disregarding the fact that the concept of psychopathy is so extended today that one can find some psychopathic traits in anyone, the addiction itself is often taken as evidence of degeneracy when psychopathy cannot be otherwise proved. This is, of course, to reason in a circle. Also when it has been demonstrated that these persons have tainted heredities, therapeutically and for prognosis very little has been gained.(23)

If one substitutes "tainted personality" for "tainted heredity" in the above statement, it can be applied without any other change to current theories of the kind under examination.

An American addict, William S. Burroughs, has expressed his views of the idea that there is an addiction-prone personality, in the following blunt language:

Addiction is an illness by exposure. By and large those who have access to junk become addicts.... But there is no pre-addict personality any more than there is a pre-malarial personality, all the hogwash of psychiatry to the contrary.... Knock on any door, Whatever answers, give it four half-grain shots of God's Own Medicine every day for six months and the so-called "addict personality" is there! (24)

In support of Burroughs' conclusions, it is generally impossible to find any adherent of the addiction-prone personality school who is willing to test his theory on himself-by the six months' test suggested by Burroughs, for example. Clearly if one does not have the special personality attributes necessary for addiction one should be immune. Nevertheless, even with the stimulus of a substantial wager, these investigators refuse to risk the experiment on themselves. This indicates one of three things: ( 1) they suspect that they may have addiction prone personalities; (2) they do not know what the type is and do not believe their own theory; or (3) those who have made the test have become addicted and changed their occupations.

In the older literature of addiction a significant aspect of the attempt to show that addicts constituted a different breed of human beings from non-addicts included the investigation of their genealogical histories. Since such studies are no longer given much attention in the behavioral sciences, I shall content myself by indicating that, when the necessity of controlled comparisons was recognized and - applied, virtually all of the claims which had been made concerning the unusual prevalence of hereditary defects in addicts dissolved. The more sophisticated studies that were made seemed to indicate that the hereditary backgrounds of addicts were not significantly different from those of normals, with the possible exception that psychotic conditions of some kinds seemed to be less frequently found in the addict's background.(25)

Selective Factors in Addiction

The purport of the preceding discussion is not that personality factors do not play any role in the process of becoming addicted. On the contrary, it seems certain that they do and that if there were personality types that could be identified objectively and reliably they would be distributed differently among addicts and non-addicts. However, the same statement would probably be true of the persons who contract venereal disease. One does not speak of a predisposing personality type as a cause of venereal disease, but it would certainly be relevant in a consideration of exposure to the disease. Personality influences may well operate in a similar selective manner in the case of exposure In addiction. However, all the types that exist in the general population also sometimes turn tip as addicts and the influence of given personality attributes varies widely in different social settings.

Besides the personality factors there are a great many other kinds of influences that operate selectively with respect to who uses drugs and who does not. Availability of the drug is such aninfluence. In the United States high availability exists primarily in two broad areas; one of these is the medical profession, the other, the underworld and the metropolitan slums. Addiction rates are comparatively high in both. Other more indirect influences are those of age, skin color, place of residence, income level, occupation, special events such as going to war or acquiring certain types of diseases, one's associates, and no doubt many others. During the nineteenth century, for example, there were more female than male addicts, the average age of users was much higher than now, Negroes were not over-represented as now, and addiction was distributed fairly evenly in the social classes and may even have been concentrated to a slight extent in the middle and upper strata. Obviously the selective processes at work must have been very different from what they now are, and there is obviously much more involved than personality types.

A study which, like those that have been cited, stresses personality predisposition, but also allows for the other influences of the type noted, is that of Chein and his associates, (26) whose conclusions were based on their well-known investigations of adolescent addiction in New York City slums. Gerard, who co-authored the final published report, presented in it the same classification of addict personality types that be and Kornetsky had previously published.

Chein evidently accepted the general purport of these findings, for be remarks elsewhere that when addicts come to psychiatric attention "they seem to be, without exception, suffering from one or another of a variety of mental disturbances, apart from their addiction .(27) Unlike Gerard and Kornetsky, Chein emphasizes.. the idea that the spread of, drug use is associated with human misery generated by the nature of life in the slums and, especially- by the nature of family life. Two moods favorable to the spread of the habit are identified: one of pessimism, unhappiness, and futility; the other of mistrust, negativism, and defiance. At the same time

he observes that only a small percentage of the boys in the areas studied (never more than 10 per cent) become addicted. He thus conceives of the personality disorders which are said invariably to precede and facilitate the addiction as natural consequences of slum life and experiences within the family.

The study by Chein and his associates, it should be recalled, was focused on adolescents in a twentieth-century urban slum. As such, it deals with a specific pattern of recruitment into the ranks of addiction that is prominent in the United States at present, but which does not encompass all existing paths to addiction and which scarcely existed throughout most of the nineteenth century. There are, for example, many European and other metropolitan slums scattered throughout the world which can at least match those of New York and in which addiction rates are probably lower than are those, for example, among physicians. From the very nature of the Chein studies, addiction among physicians, in foreign countries, among hospital patients, in non-slum, non-urban environments, in the upper classes, and in past periods of time, were not taken into account.

The Chein studies, thus, were not, and did not really purport to be, of addicts in general. The conclusions which they generated do not constitute a universally applicable theory of the mechanisms of the addiction process, but are rather descriptions ofselective processes, operating within a particular social environment in contemporary American society and applicable to some addicts but not to all and possibly not even to most of them.

A Psychoanalytic Perspective

While the views of Sandor Rado on addiction have commonly been spoken of as a "theory" of the etiology of drug addiction, it appears that Rado himself regarded them as something other than that. In a 1963 article Rado observed: "though the etiology of narcotic bondage is still unknown, its clinical feature is obviously the victim's craving: if we could stop his craving he would no longer be in bondage " (28) What Rado evidently seeks to do is to indicate, in psychoanalytic terms, how the craving for drugs is integrated in the motivational structures of the addicted person. Since Rado is not concerned with the origin of the craving, which is the central concern of this study, his views are not directly competitive and are only occasionally of theoretical relevance here.

In an earlier article, Rado suggested that all types of drug craving be regarded as varieties of a single disease which he proposed to call "pharmacothymia." Noting the addict's typical fluctuations in mood between a state of elation or euphoria and one of depression, he characterized the "megalomania of pharmacothymic elation" as a manifestation of narcissistic regression. For many years, Rado says, he could not understand why the addict did not simply quit his habit when continued use of the drug bad demonstrated to him that the initial elation disappears and that his hopes concerning it bad been delusional: "A patient himself gave me the explanation. He said, 'I know all the things that people say when they upbraid me. But mark my words, doctor,nothing can happen to me.' . The elation bad reactivated his narcissistic belief in his invulnerability."

Rado' describes the attainment of pleasure from the drug as "an artificial sexual organization which is autocratic and modeled on infantile masturbation. . . . The ingestion of drugs, it is well known, in infantile archaic thinking represents an oral insemination; planning to die from poisoning is a cover for the wish to become pregnant in this fashion. We see, therefore, that after the pharmacothymia has paralyzed the ego's virility, the hurt pride in genitality, forced into passivity because of masochism, desires as a substitute the satisfaction of child bearing."(29)

In the 1963 article, Rado refers to the psychoanalytic doctrine that in the initial experiences of manipulating his own limbs the child comes to believe in his omnipotence and that this is his first self-image or primordial self. The addict's experience of gratification or narcotic grandeur from a fix is said to reactivate the feeling of omnipotence of the primordial self, making the satisfied addict feel like the "omnipotent giant" he bad always fundamentally thought he was .(30) Rado concludes that the response of narcotic grandeur is elicited only in a small minority of persons who retain a more powerful primordial, omnipotent self than is the case with the vast majority. He notes, however, that some persons who become addicts evidently do not possess this predisposing trait and do not develop narcotic intoxication or experience narcotic grandeur.

From the perspective of the theory concerning the nature and origin of the craving for drugs that has been outlined in previous chapters, it might be expected that this irrational and powerful impulse would be symbolically elaborated by the person subject to its influence and that it would become a pervasive aspect of his personality structure as the latter is viewed by psychiatrists. Rado's interpretation would not be accepted by psychiatrists committed to other ideological positions, and it is bard to see bow it could be subjected to any sort of empirical verification. This, however, need not concern us here. The important point to be kept in mind concerning Rado's work is that it is concerned essentially with the consequences of addiction, not with its antecedents. This is the clear import of his own remark that the etiology of addiction is unknown.

The Pleasure Theory

It is a common belief that opiate addiction is based upon the pleasure or happiness which the drug is supposed to produce. In a sense, this view is incontestable, for obviously the user of drugs obtains satisfactions of some sort or he would not be addicted. The satisfaction of the addict's craving for drugs may itself be called a pleasure. The relief from withdrawal distress which an injection gives may also be so designated. So considered, the assertion that an addict uses drugs because be obtains pleasure or satisfaction from them is merely a tautology.

If one views this theory as a serious attempt at causal explanation it has grave faults. Virtually all addicts maintain, for example, that they feel only "normal" under the influence of the drug after the initial interval when addiction is being established. This contention can scarcely be denied, for, after all, the addict is the final authority on this question of how he feels.

Nevertheless, Ausubel ventures to disagree with the addict about how he feels. Noting that addicts as a group maintain that the kick disappears and that the drug is used, when dependence is fully established, merely to feel "normal," he suggests that they are untruthful. Faced with data that do not conform to his theory, Ausubel alters the data rather than his views by inventing "a lesser residual euphoria, possibly devoid of the original voluptuosity" that always remains. The addict's claim, he argues, "sounds very unlikely when one considers the tremendous cost in money and social prestige, as well as the risk of imprisonment and disgrace involved-all of which could be avoided by simply undergoing the moderate and self-limited physical suffering of withdrawal ."(31)

Because addicts have a bad reputation for veracity and because they rarely read or write articles in learned journals, there is little hazard attached to attributing wholely imaginary subjective effects to the drug. Indeed, this is more or less required in the mass media catering to popular tastes, since the general public commonly assumes that the mysterious power of the habit must be based upon an equally mysterious and uncanny pleasure. The writer who in one paragraph describes addicts as living in a state of ecstasy may in the next elaborate on the disaster, disgrace, and misery that addiction entails. Anyone with minimal knowledge of the conditions under which American addicts live could not possibly characterize them as anything but miserable. If they use the drug for pleasure in the usual sense it is certainly not evident in their lives. Obviously, if they were suddenly to begin to act so as to maximize their pleasures and minimize their pains and sorrows, they would all quit their habits.

The idea that the power of the opiate habit rests upon the pleasant state of mind that it engenders shatters upon the fact that there are substantial numbers of addicts who state that they have never experienced euphoria from the drug and the fact that the initial euphoria vanishes either entirely or almost entirely in confirmed addiction. Reports of the absence of any euphoric experiences are particularly common from persons who first begin to use an opiate to relieve severe organic pain, who use it by other than the intravenous route, and who are not members of the addict subculture. Thus, a prominent member of the New York Bar, cited by Bishop in 1921, stated flatly," I have never experienced the slightest pleasurable or sensually enjoyable sensations (32) from the administration of morphine....

A noted investigator in the field, Abraham Wikler, over a period of many years of research, has come to a conclusion much like mine concerning the inadequacy of the pleasure theory. When the first edition of this book was published in 1.947, however, Wikler had a different opinion and dismissed my contention that it was the relief of withdrawal that created the hook in addiction. Subsequently, perhaps in large part because of an experiment that he performed at Lexington in which he permitted an addict inmate to administer to himself the drug of his choice, his views changed. He found that while the addict accepted the opportunity to use drugs with alacrity and anticipatory pleasure, after a few days of use he became morose and unhappy-a fact which showed up not only as direct statements in the interviews but also in the subject's dreams. (33)

The development of Wikler's thinking on this matter is interestingly brought out if one compares his earlier publications with his later ones. (34)

A German physician and ex-addict protested as follows against the notion that an addict uses drugs to produce in himself a pleasant state of mind:

How false it is to say of a drug addict that he takes his injections to produce a "pleasurable state of mind." Good heavens! If people only knew how much misery it causes the addict each time he has to take the drug, they would not say this, True, that the first few injections cause some users to feel stimulated, alert, and so on. However, as soon as tolerance is completely established the euphoria vanishes. When this point is reached, the addict takes his morphine in the same spirit that the prisoner carries his chains. One would then have to use the term "euphoria" to refer to the fact that the distress of abstinence disappears after the injection, but by the same logic any person with a headache could be said to experience euphoria when it disappeared. According to such a standard every normal man spends his whole life in a state of euphoria. . . . And it is entirely false to believe as people do, that addicts use drugs to produce pleasurable sensations. Every addict who hears- people talk in these terms, sighs and holds his peace. (35)

Some persons become addicts without ever becoming aware of the euphoric effects of the drug which are alleged to be the cause or basis of addiction. This is often the case when drug users have first used the drug in connection with serious and painful disease or when they were semiconscious or unconscious when they received their first injections. As a German physician correctly observed:

A fundamental fact that must be added here is that the experience of euphoria is by no means a necessary precondition for the development of a craving. In addition to the fact that some people develop a desire for sedatives which never produce euphoria, I am acquainted with morphine users who have never, throughout the long period of their addiction, experienced any euphoria from the drug. In the case of most addicts, whatever pleasurable effects may be experienced are of short duration. Morphine addicts have become addicts after reacting to first injection with dizziness, painful vomiting, and headache, rather than with pleasure. (36)

As in the case of alcoholism, the persons who experience the pleasurable effects of morphine alone are never addicts. The casual or social drinker who drinks a few cocktails is exhilarated and stimulated by them and suffers few if any bad effects. The chronic alcohol addict, on the other band, suffers severe aftereffects in the form of physical symptoms, and the social effects may be serious as well. Similarly, it is the non-addict who experiences the beneficent effects of morphine with few or none of the evil effects which are so prominent in the case of the addict. The benign effects of morphine are well recognized in medical practice. Whatever unpleasant effects may follow from the medical use of a few injections of opiates are slight, and are in any case usually not recognized by the patient. On the other hand, the opiate addict himself describes the vast evil social and physical consequences that his habit brings upon him.

From the standpoint that emphasizes the pleasures produced by drugs as the key to understanding addiction, a drug such as marihuana should be intensely addictive, since the pleasurable sensations it produces are comparatively pure and uncomplicated by adverse physical consequences, and there is no withdrawal distress. Yet, it is well known that the addictive powers of marihuana and other drugs like it are negligible by comparison. Indeed, these drugs are described as nonaddicting.

It is sometimes said that only pathological persons experience pleasure from opiate drugs. This contention is manifestly incorrect, as anyone can find out for himself by talking with acquaintances who have bad morphine injections or by talking to a few experienced nurses. Almost all persons who had had morphine injections with whom I discussed the matter described the effects as pleasant, and some found them intensely so. It is usually reported that, if allowances are made for some unpleasant effects with the very first injections, the vast majority of patients experience the initial effects as pleasurable. Retrospective reports of addicts indicate that the initial experiences of addicts cover the entire range of possibilities from those that are intensely pleasurable to those that are decidedly unpleasant. In some cases no effect is noticed.

Addiction as an Escape

The assertion, which is commonly made, that drug addiction is an "escape mechanism" is evidently based upon the assumption that the drug user's assertion that he feels "normal" is false. It implies that by means of drugs a person can escape from the problems that harass him when he is not using drugs, into a realm of fantasy or pleasurable physical sensations which allow him to forget his inadequacies and his problems. As already indicated, there is no evidence that such a mental state is produced in morphine addicts. There is a great deal of evidence to indicate that it is not. Moreover, the drug user is fully aware of the disastrous effects of his habit, particularly upon his social life. It is therefore difficult to see how the drug habit can be regarded as an escape mechanism, since it does not produce forgetfulness as alcohol does, and since the habit itself constitutes a burden and a problem which is usually more serious than those for which it is alleged to provide an escape. It is true that there may be a parallel between the use of alcohol and the initial use of opiates, and that opiates may be used as an escape device before addiction is established. Morphine as used in hospitals is a potent escape device, enabling patients to escape from intolerable pain, from worry, insomnia and so on. When addiction is established, however, this effect is no longer present.

Lower Animals as Addicts

Dr. S. D. S. Spragg described the effects upon chimpanzees of repeated doses of morphine .(37) He claimed that be found unequivocal evidence in the behavior of chimpanzees of a "desire for morphine" and therefore insisted on calling them addicts. He concluded:

A discussion of the nature of morphine addiction in chimpanzee and man was undertaken, and the thesis was defended that morphine addiction is fundamentally a physiogenic phenomenon, developed according to principles of association. That the "societal" factor (which is usually present in human addiction) is not essential in the development of addiction has been demonstrated by the present results.(38)

Spragg taught his chimpanzee subjects to associate withdrawal distress with the hypodermic injection of morphine. He contended that they exhibited genuine addiction behavior in the following ways:

(1) By showing eagerness to be taken from the living cage by the experimenter, at the regular dose times or when doses are needed, in clear contrast to behavior exhibited when taken from the cage at other times; (2) by struggling, under such conditions, to get to the room in which injections are regularly given; tugging at the leash and leading the experimenter toward and into that room; and exhibiting frustration when led away from the injection room and back to the living cage without having been given an injection;(3) by showing eagerness and excitement when allowed to get up on the box on which the injections were regularly made, and more or less definite solicitation of the injection by eager cooperation in the injection procedure or even by initiation of the procedure itself; and(4) under controlled test conditions, choosing a syringe-containing box (whereupon injection is given) in preference to a food-containing boxe. (39)

The choice of food or drugs was offered these chimpanzees under four conditions: (1) when they were hungry and also in need of a dose; (2) hungry, but bad recently been given an injection of morphine; (3) recently fed, but in need of a dose; and (4) recently fed and recently injected. Spragg anticipated that the chimpanzees would choose food under conditions (2) and (4) and drugs under conditions (1) and (3). His expectations were fulfilled in the course of the experiment, leading him to the conclusion that the desire for morphine bad been unequivocally established and that the animals' behavior was essentially like that of human addicts.

There are a number of serious objections to Spragg's conclusions which make it necessary to reject them. In the first place, the assertion that the chimpanzees desired morphine injections involves the fallacy of projecting human attributes onto the animal subjects. On the basis of experimental evidence alone, Spragg might have concluded that the chimpanzees exhibited a desire to be pricked with a hypodermic needle. A second objection to Spragg's conclusions is that hospital patients to whom drugs have

been given regularly for a short time frequently demand that the injections be continued and object strenuously if they are not. Such patients by no means necessarily become addicted, yet their behavior is essentially like that of Spragg's animals. Hospital patients, under the conditions mentioned above, do not become addicts if they are kept in ignorance. It is also possible to satisfy them by giving them other drugs than opiates. Spragg's assumption that the choices made by the chimpanzees are those which an addict would make under the same conditions is incorrect. American drug addicts, if given the choice of food or drugs when (1) hungry or suffering withdrawal distress, (2) hungry but not suffering withdrawal, (3) not hungry but suffering withdrawal symptoms, and (4) neither hungry nor suffering withdrawal distress, would unquestionably choose drugs Under all four conditions provided that the other conditions of the experiment were identical with those imposed upon the chimpanzees. Spragg's results therefore demonstrate an essential difference between the animals and human beings, not a similarity, as Spragg assumes.

Spragg mentions that the chimpanzees did not conform to one of the criteria of addiction as we have defined it, namely, the tendency to relapse. As a matter of fact, however, none of the criteria of our definition were applicable to his chimpanzees.(40)

Subsequent to Spragg's study, there has been a great deal of highly interesting experimental work done on the responses of lower animals to the regular administration of opiates, especially morphine. Allusion has already been made to some of this work in which the gap between human and animal responses to morphine has been further narrowed by the fact that relapse behavior has been induced in lower animals. Some of the investigators in this area speak of their animals as "addicts" and insist or imply that their behavior is essentially identical with that of human addicts.

Such a claim is comparable to a similar claim that is made with respect to so-called homosexuality in lower animals. These conclusions should be regarded as hypotheses to be tested by detailed empirical comparison of the behavior of human and animal subjects, and not asserted simply on the basis of systematic information obtained from animal experiments related to a few selected aspects of human addiction. If a rat that behaves as did some of those that Nichols (41) trained is to be called an addict, there should be no sense of anomaly or absurdity in the idea of arresting rats as violators of the narcotic laws.

The definition of addiction that was developed in an earlier chapter, and which is much like those proposed by others, included five items which were thought to be characteristic and common features of addiction behavior. Before lower animals can be said to exhibit behavior that is identical with that of human subjects it is reasonable to require that a behavioral comparison be made on all of these five points. The claim, however, is based on only one of them, namely, relapse, and even in this case the evidence presented by Nichols is equivocal. For example, after the training period had ended and drug intake had been stopped, the rats did voluntarily choose to drink much more of the morphine, but the amount diminished rather rapidly from the fourteenth day after withdrawal to the forty-ninth. While Nichols assumed that the withdrawal symptoms had disappeared, it is well known that they do not disappear in all human subjects in 49 days but may last as long as four or five months or even longer. This suggests that the tendency of the experimental rats to drink the morphine solution may have been linked with residual withdrawal symptoms and may subside as they diminish and disappear. The tendency of human users to relapse because of lingering withdrawal symptoms presents a close parallel, but the human subjects also relapse after many years of forced or voluntary abstinence.

If one supposes a hypothetical experiment with human subjects like that performed by Nichols, and supposes that the subjects knew just as little about the drug and what was happening to them as the rats did, it is certain that no one acquainted with the behavior of the average American addict would be willing to say that such subjects were addicts in the same sense. Indeed, it is well known that morphine-dependent hospital patients who are kept in total ignorance of the drug and of withdrawal distress sometimes demand injections or "medicine" to relieve withdrawal symptoms when they are unaware of the nature of the medicine and of the discomfort they experience. The insistence of the demand tends to be proportional to the severity of the symptoms and to decline as they subside. If, after a period of time, such a patient were allowed to have his way, he might well resume the medication or "relapse" into regular use of the drug. Relapse of this sort does not constitute addiction in human subjects, since such patients can still be successfully withdrawn without being any the worse or the wiser for their experience. Such resumption of drug use is qualitatively far removed from the superficially comparable behavior of addicts, and it leads to few or no important long-range behavioral consequences. Such patients also do not think of themselves as addicts or even suspect that they may be. This matter of self conception, which is an integral aspect of human addiction with vast social and behavioral consequences, does not, of course, arise in experiments with lower animals, but clearly it has to be considered before human and animal responses can be declared to be identical or equivalent.

It is difficult and hazardous to extrapolate to human subjects findings obtained from observing lower animals in highly contrived experimental situations in which human beings are never placed. Most investigators, in fact, avoid doing this. The difficulties involved in such extrapolation, and in determining what experimental findings mean, is well illustrated by the differences between Spragg's and Nichols' findings with regard to relapse. If rats relapsed for Nichols, why did the chimps not relapse for Spragg? Another example is provided by the extensive work with monkeys trained in the self-administration of drugs. (42) In some of these experiments the caged animals had an apparatus fastened on their backs that was arranged to permit them to move about freely and to obtain an injection any time they wished by pressing a lever. In this situation monkeys routinely take morphine injections regularly to the point of physical dependence and continue the injections over considerable time periods. If they are withdrawn and after a time are put back in the same situation they promptly resume the injections. In general, monkeys show a liking for the same drugs that humans use for kicks and reject the others. The equivocal significance of these experiments with respect to human subjects is suggested by the fact that monkeys go on giving themselves injections of cocaine and other nonaddicting drugs in much the same way as they do with morphine, thus obscuring the difference between drugs that produce physical dependence and those that do not. It is hard to imagine a similar experiment with human subjects that would justify a valid comparative judgment.

Conditioning Theory

As would be anticipated, those investigators who attempt to generalize about both human and lower animal responses to opiates from data secured primarily from observing lower animals usually interpret their findings in terms of the standard concepts of conditioning or reinforcement theory. Since the latter is itself mainly derived from experimental work with lower animals, it is formulated in terms of concepts that are equally applicable to man and animal and characteristically makes no or few allowances for the effect of any of the special attributes or capabilities of human beings which distinguish them from lower animals. Of particular importance to the analysis of opiate addiction is the conditioning theorist's lack of attention to cognitive behavior.

If it is conceded that nearly all human beings are more intelligent than any animal, it may be proposed that it is not unreasonable to expect this to make a difference in the way in which conditioning or reinforcement operates. From what is known about complex human conduct, it is abundantly clear that stimuli and situations affect it primarily as they are understood or interpreted by the subject. The argument that I have developed with respect to the role of withdrawal distress in addiction is simply another instance of this point. So also is the argument that the addicting effect which the relief of these symptoms has depends upon how it is interpreted.

In the process of reformulating my view of addiction as a type or instance of negative reinforcement theory of the operant conditioning variety, Nichols emphasizes that his rats had to initiate action, that they were not passive recipients of the drug, but self injectors. "Sustained opiate directed behavior" is established, be reasons, by the repeated reduction of drive (withdrawal) which immediately follows the injections and reinforces the original operant act of taking the first shot. In the human addict, he argues, as I have, that the injections are also used to reduce anticipatory anxiety prior to the actual onset of withdrawal or to avoid withdrawal. Further generalization of the response leads the addict to resort to the fix as a sovereign remedy for almost any distress or anxiety.

Nichols tacitly assumes throughout his discussion that the perceptions of the animal and of the human drug user are largely irrelevant and that the cognitions of the human subject, his knowledge or ignorance of the drug and the distress, and the manner in which be conceives his experiences, are of no critical significance. This is the central point of difference between his position and mine. Nichols explains the absence of relapse in Spragg's chimps as a consequence of their being relatively passive recipients of the drug rather than taking it by themselves, an unconvincing explanation since they did exert themselves considerably to obtain shots when they needed them.

An alternative explanation that seems applicable to both human and animal subjects, and that is consistent with the fact that passive human recipients of the drug do become addicted and that some of those who actively seek it and take it themselves do not, is that the organism's selfinitiated actions influence its perceptions or understanding of the situation. The brighter human subject is likely to have acquired sufficient knowledge of drugs so that be grasps the situation even when be is a passive recipient; the animal, on the other band, because be is not nearly as bright, has difficulty making even some of the most rudimentary associations. The elaborate experimental situations in which animals are enabled to give themselves injections may function as they do simply because they facilitate the learning or grasping of some of the associations or connections between events that are necessary preliminary steps on the path to genuine addiction. These associations are made quickly and almost routinely by most human subjects without artificial aids.

The "Evil Causes Evil" Fallacy

It is widely and commonly assumed that anything that encourages or facilitates the use of addicting drugs is ipso facto evil like the drug habit itself. This frame of mind makes it easy to accept ideas such as that human misery, personality defects, double failure, slum conditions, disorganized family life, and a host of other similar undesirable conditions are contributing factors or "causes" of addiction. Personality traits described as a carefree attitude, willingness to experiment, or as a desire for new experiences and pleasures, are frequently cited as features of the addiction-prone personality and as character or personality defects. The same traits in non -addicts are often admired. The experimental frame of mind which leads young people to try LSD, marihuana, and other drugs also prompts them to become scientists, creative artists, reformers, or innovators. A carefree attitude and an interest in new experience on the part of wealthy businessmen is generally applauded. The search for pleasure, even by chemical means, is a popular national pursuit, as the statistics on alcohol consumption alone are sufficient to indicate.

Another example of the same type is provided by those who, with the advantage of hindsight, reproach the users of drugs who have become addicted for their willingness to violate the law and to take risks. These tendencies are also viewed as personality or character defects. Willingness to take risks, however, is apparent in a large proportion of the population and is a pervasive aspect of living. It is evident, for example, in politics, in international affairs, in marriage, in business and financial operations, in exploration, mountain climbing, sports, racing automobiles and airplanes, and in dozens of other activities and occupations. The persons who accept and even enjoy risk often become heroes if they survive. At another level, millions, by smoking tobacco or drinking alcoholic beverages, seem to accept the accompanying risks. Even the willingness to violate laws is not wholly or absolutely bad, since it has, in the past, often led to innovation and progress.

The "evil causes evil" attitude, by subtly leading people to misconceive the traits, feelings, appearance, actions, and motives of drug addicts causes them to think of drug users as a breed apart from ordinary normal people. The same tendency exists with respect to criminals and prisoners. This is perhaps why one of the most common reactions of the average citizen when he first visits a penitentiary or a place like Synanon where live addicts can be seen and talked to is one of surprise. The prisoners and the addicts, he discovers, are very much like other people, and, like other people, each is different from all the others. Whatever weaknesses, faults, or frailties of character or personality he may note do not surprise or shock him too much because they are already familiar to him, either because he has them himself or because he has observed them among his friends and associates.

The earlier pages of this chapter provide a number of illustrative instances of the fallacy that has been described. Numerous other examples can be found in the popular and scientific literature on addiction, as well as in that on almost any other form of deviant and heavily stigmatized behavior.

3. E. W. Adams,Drug Addiction (London: Oxford University Press,19-37), P. 53.

4. Lawrence Kolb, -Types and Characteristics of Drug Addicts,"Mental Hygiene (1925), 9: 301.

5. Lawrence Kolb, "Drug Addiction in Its Relation to Crime,"Mental Hygiene (1925), 9: 77.

7. "Types and Characteristicsof Drug Addicts," op. cit., p. 302.

8. "Drug Addiction: A Study of Some Medical Cases,"Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry (1928), 20: 171-83

9. "Clinical Contribution to Drug Addiction: The Struggle for Cure and the Conscious Reasons for Relapse,"Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease (1927), 66: 22 ff., quoted by Terry and Pellens, op.cit., p. 617 ff. The lowest percentage of abnormals among addicts that I have been able to ascertain, as reported by a competent authority, is 34 per cent, as reported by R. N. Chopra in "The Opium Habit in India,"Indian Journal of Medical Research (October,1935), 23: 357-89, Kolb's 91 per cent is the highest. Other estimates were made by Theodore Riechert, "Die Prognose der Rauschgiftsichten,"Archiv fur Psychiatric (1931), 95: 103-126; Hans Schwarz, "Ueber die Prognose des Morphinismus,"Monatschrift fur Psychiatrie und Neurologie (1927), 63: 180-238; H. M. Pollock, "A Statistical Study of One Hundred Sixty-four Patients with Drug Psychoses,"State Hospital Quarterly (1918-1934, Pp. 40-51; Johannes Lange and Emil Kraepelin, as cited by Alexander Pilcz, "Zur Konstitution der Suchtigen,"Jahrbucher fur Psychiatrie(1934), 51: 169 ff; V. V. Anderson, "Drug Users in Court,"Boston Medical and Surgical journal (1917), 176: 755-57; Karl Bonhoeffer, "Zur Therapie des Morphinismus,"Therapie der Gegenwart (1926); 67: 18-22; see also Terry and Pellens, op.cit., index, under "psychopath" and "psychology."

10. Quoted by Terry and Pellens, op. cit., pp. 617-23.

11. Charles Schultz in "Report of Committee on Drug Addiction to Commissioner of Correction, New York City," American Journal of Psychiatry (1930-31), 10: 484.

17. Ibid., p. 39.

18. Ibid., pp. 50-51.

19. Ibid., p. 40.

20. Ibid.

21. Terry and Pellens Op. cit., pp. 513-16.

22. Ernst Meyer, -Ueber Morphinismus, Kokainismus, und den Missbrauch anderer Narkotika,"Medizinische Klinik (1924), 20: 403-407.

25. See, for example, Otto Wuth, Erbanlage der Suchtigen Zeit schrift fur the Gesamte Neurologie und Psychiatric (1935), 153: <02 ff., and Mark Serejski, "Ueber die Konstitution der Narkomanen," Zeitsclzrift fiir die gesamte Neurologie und Psychiatrie (1925), 95: 130-50.

29. "The Psychoanalysis of Pharmacothymia," Psychoanalytic Quarterly (1933), 2: 1-23.

31. David P. Ausubel, "The Psychopathology and Treatment of Drug Addiction in Relation to the Mental Hygiene Movement," Psychiatric Quarterly Supplement (1948), 22 (2): 219-50.

32. Ernest S. Bishop,The Narcotic Drug Problem (New York: Macmillan, 1921), P. 138.

33. Abrabam Wikler, "A Psychodynamic Study of a Patient During SelfRegulated Readdiction to Morphine,"Psychiatric Quarterly (1952), 26: 270-93.

35. Otto Emmerich, Die Heilung des chronischen Morphinismus (Berlin, H. Steinitz, 1894), P. 123-4.

37. S. D. S. Spragg, "Morphine Addiction in Chimpanzees,"Comparative Psychology Monographs (April,1940), vol. 15, no.7.

42. See, for example, M. H. Seevers, "Opiate Addiction in Monkeys: Methods of Study," Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics (1936), 56: 147, and, by the same author, Chapter 19 in V. A. Drill (Ed.), Pharmacology in Medicine (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1958). Also, T. Thompson and C. R. Schuster, "Morphine SelfAdministration, Food-reinforced, and Avoidance Behaviors in Rhesus Monkeys,"Psych opharm acologia (1964), 5: 87-94.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|