Report 5 Definitions

| Reports - A Report on Global Illicit Drugs Markets 1998-2007 |

Drug Abuse

2 Definitions

Unintended refers to a state of mind, an expectation. There is however not a single decision maker for these policies or interventions. To substantiate a claim of “unintended”, one might refer to documents that describe the predicted and desired consequences of a programme. However many of the interventions discussed here are not the results of explicit and documented decisions. For example, a police department might increase arrest rates of cocaine dealers by dispatching more officers to a location frequently used by cocaine dealers without having to provide a specific assessment of the likely consequences of doing so. Even at the broader level of international interventions, aimed for example at opium production in Afghanistan, there is no obligation of governments to prepare, let alone publish, full assessments of the intended consequences.

Instead, we make general inferences based on agency statements on specific interventions. For example agencies discussing their decisions to increase treatment will refer to reductions in crime and in certain risk behaviours, as well as drug use, so the crime and risk effects are not unintended.4 The funding of a new integrated drug control agency in Tajikistan is intended to cut corruption in that country’s drug enforcement as well as reduce the flow of heroin to Russia, so integrity enhancement is an intended effect.

Intent and predictability need to be distinguished.5 No policy intends to increase the spread of HIV but many analysts assert that a prohibition on syringe exchange programmes (SEP) will facilitate the spread of HIV.6 Advocates for an SEP ban might even agree with that prediction (though this is contentious) but still claim that there are ethical reasons for the government to ban the facilitation of a banned behaviour. Thus we treat the spread of HIV as an unintended but predicted consequence of a prohibition on SEPs. Tonry (1995) makes a similar distinction in his analysis of the predictably disproportionate effects of US federal mandatory minimum penalties on African-American users and sellers, a pattern he calls “malign neglect.”

Policy may be usefully defined as the explicit actions by the government, classified into laws and programmes (Kleiman, 1992). Laws can have effects even without explicit implementing programmes. Notably the decision to prohibit drugs engenders many consequences even if the enforcement is minimal.

Thus an important distinction is between consequences that arise from prohibition itself, as opposed to those resulting from specific implementing programmes. For example, prohibition itself ensures that government cannot regulate quality of the product7 or require labelling; this effect is not much worsened by tougher enforcement.8 More subtle is the effect on the growing of illegal drugs. Coca production in its current forms is considered environmentally damaging. The coca bush exhausts the soil relative rapidly (Leons & Sanabra, 1997) and the chemicals used to extract the alkaloid from the leaf are disposed of in damaging ways. If cocaine were legal, then it might be grown in places9 and in forms that would lead to less environmental degradation. Thus some of the environmental damage may be seen as a UC of prohibition itself. The problem is exacerbated by efforts to eradicate, whether manual or aerial. These lead to additional clearing of the forest in vulnerable areas, as a higher acreage has to be cultivated in order to obtain a given output.

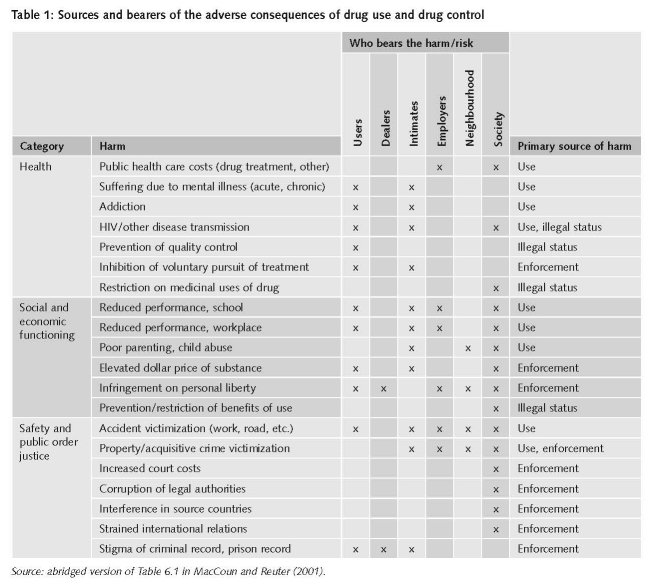

MacCoun and Reuter (2001) make that distinction in identifying the sources and bearers of over 50 specific harms associated with contemporary drugs in the United States10. Their analysis distinguishes three potential sources of harms: drug use itself, prohibition and enforcement. Bearers are divided into four categories: users, intimates, neighbours and society generally. Table 1

presents an abridged form of that table.

4 See for example the publications of the United Kingdom Treatment Agency such as www.nta.nhs.uk/publications/documents/nta_treatment_outcomes_what_we_need_to_know_2005_te2.pdf

5 A useful discussion of these matters, aimed at policy analysts, can be found in Bardach (2008).

6 See for example Committee on the Prevention of HIV Infection among Injecting Drug Users in high-Risk Countries (2006).

7 Efforts to provide test data on the composition of party drugs, as has been condoned by the Dutch government in recent years, is a small exception to this statement (CITE).

8 It can be argued that tougher enforcement will lead to greater dilution and hence greater variability of quality; however that is a modest change compared to the loss of quality control consequent on prohibition itself.

9 Historically, coca has been grown in Java, Formosa and Bengal under various colonial auspices in the early part of the twentieth century. Though there is no description that would allow a definite assessment of the environmental consequences, it seems likely that these would have been less sensitive areas than those currently used for clandestine coca growing.

10 The four major harm categories are health, social and economic functioning, safety and public order, and criminal justice.

Though MacCoun and Reuter do not separate intended from unintended harms, clearly many of the harms identified are unintended. This report expands the analysis to include sources of possible unintended benefits; thus we also include treatment and prevention programmes as having possibly unintended effects.

Consequences are effects on social wellbeing that are large enough to be valued by society. While few doubt that the crimes committed by drug users to support expensive habits constitute an important unintended consequence of the prohibition of heroin, other consequences that may well be predicted and articulated may simply not be large enough to be worth accounting for. For example, marijuana is used in some countries (e.g. the Netherlands) as a minor therapeutic agent for some diseases. In others, notably the United States, because the drug is so marginalised/demonised, its therapeutic potential has hardly been explored (Joy, Watson and Benson, 1999). One might then take the loss of marijuana as a drug for dealing with such medical problems as AIDS Wasting Syndrome, glaucoma and the side-effects of chemotherapy as an unintended consequence. However though in the United States this has proven a major policy battleground, the therapeutic value of the drug does not seem significant enough to include it on the list of unintended consequences.11

11 There is a different unintended consequence associated with the medical marijuana movement. In the United States the principal advocates for making marijuana available for therapeutic purposes have been drug policy reform groups rather than groups associated with specific medical problems. Many observers believe that the advocates’ interest is primarily in easing access to the drug for recreational purposes (see Samuels, 2008). Thus prohibition may perversely have increased therapeutic availability of the drug.

3 A taxonomy of mechanisms

These consequences are of policy value for two reasons. First, they should be taken into account when policy decisions are made. Second, these unintended but predictable negative effects should be ameliorated where possible. In order to accomplish the latter, it is important to identify the sources of those consequences as well as who is affected.

Some consequences are the result of behavioural changes of participants brought on by policies. For example, tougher enforcement (whether a higher probability of arrest or a longer sentence on conviction) increases incentives for taking violent action against other market participants who might be informants.12 Thus tougher enforcement may increase the number of killings and injuries in drug markets as a result of participant actions in response to the policy.13

The iconic harm reduction programme, needle exchange, is a response to a behavioural adaptation by users. If policing makes needles hard to obtain or if needle possession is taken as evidence of drug use, then injecting drug users will economize on needle purchase and possession by sharing them with others. This has been a major vector of transmission of AIDS in a few countries, notably the United States.14

Other examples of such behavioural changes include:

• An increased interest in drugs because they are prohibited, what is often referred to as the “forbidden fruits” effect (MacCoun and Reuter, 2001);

• Disintegrative shaming effects (Braithwaite, 1989) where stigmatizing users further marginalizes them from mainstream society, weakens the bite of informal social controls, discourages them from seeking treatment, etc.;

• Distorted messages about relative drug risk and risk management:

- The very clarity of the law creates the false impression that alcohol is safer than it really is;

- Difficulty of conveying messages about safe-use practices.

More subtle effects of behavioural responses can also be identified that work through market forces. For example, it appears that increasing interdiction rates for cocaine smuggling will lead to greater export demand for Colombian cocaine. The paradox is easily explained. Seizing a higher fraction of shipped cocaine has two effects on the export demand for Colombian cocaine. On the one hand it increases the number of kilos that have to be shipped in order to deliver one kilogram to U.S. consumers; that raises export demand from Colombia. On the other hand the higher price that smugglers have to charge in order cover their increased replacement costs may lower U.S. consumption and thus reduce the export demand. It turns out that under reasonable assumptions about the cost structure of cocaine smuggling and the elasticity of supply of coca, the first effect will be larger (Reuter, Crawford and Cave, 1988; Appendix B). Thus Colombia will produce and export more cocaine as the result of a more effective U.S. interdiction programme. It is not the result of adaptive behaviour by participants trying to mitigate the effects of the policy but simply of the logic of markets.

Another category of UC results from the behavioural changes of non-participants. If tougher enforcement against street markets leads to greater violence, then there may be out-migration of uninvolved households from the targeted neighbourhood. That out-migration is itself a potentially important consequence and may generate other effects, for example increasing the number of abandoned buildings and the attractiveness of the specific neighbourhood for continued dealing as the neighbourhood attracts a more socially marginal population.

Other UCs are not the result of actor response to incentives but of programme characteristics. For example, some negative environmental effects of spraying coca or poppies15 are simply the result of the inevitable frailties of complex programmes executed under difficult circumstances. Coca is not planted well separated from legitimate crops, often of other farmers. Spraying when pilots are concerned with being shot at is sometimes inaccurate. Wind conditions can change suddenly. Intelligence about what is coca cultivation can prove erroneous. As a consequence it is predictable that some innocent farmers will lose legitimate crops, an unintended consequence.16 If the herbicides have adverse health effects, those are also a consequence of the programme itself.

12 It is less clear whether other kinds of market violence, primarily disputes over territory or individual transactions, are affected. If tougher enforcement raises prices, which it theoretically should do but for which effect there is minimal evidence, then certainly transactional disputes will involve higher stakes and may be more likely to generate violence.

13 No study has attempted to identify the relationship between enforcement intensity and drug market violence, both of which are difficult to measure.

14 Another enforcement related AIDS transmission mechanism has been found to be important in the U.S., namely mass incarceration. High rates of incarceration have been found to explain differences in AIDS rates between the African-American and white populations in the United States (Raphael and Johnson, forthcoming). It is difficult to know how to classify the mechanism; the transmission is through homosexual activities that are engendered and facilitated by incarceration. It is a behavioural response but not related to drug use or sale.

15 These effects remain a matter of dispute, with the U.S. government maintaining that they are quite modest. For a summary see Jelsma (2001). An official refutation of the claim is offered in Inter-American Drug Abuse Control Commission (2005).

Programme management may generate unintended consequences. Large black markets generate incentives for corruption, both at the political level in producing countries and at the enforcement level in consuming nations. The corruption can be subtle in nature. In the United States local police departments have the authority to seize financial assets from suspected drug dealers and use them for any law enforcement purpose. Though in principle any wrongful seizure can be corrected through formal appeal, there is evidence that some police agencies are misusing this power in order to generate larger budgets (Economist, 2008)

Other negative unintended consequences are inherent in the intended consequences and reflect neither implementation problems nor behavioural responses. Locking up drug dealers (aimed at raising prices, reducing availability and implementing just desserts) means that those individuals will function less well later in the workforce and that children will lose time with their parents. Whether these are large effects depends on what kinds of jobs the drug dealers would have in the absence of incarceration and how good they are as parents when not locked up; drug dealers often have minimal education and job skills and can be neglectful or abusive parents in part because of their own drug habits. Again, this is not an assessment of the desirability of incarcerating drug offenders but simply a statement of an unintended consequence that might be considered in a cost-benefit analysis.

A relatively new effect that is now prominent arises from adaptation in technology induced by enforcement. Methamphetamine consumed in the United States was for a long time produced in large laboratories in Mexico, using imports of precursors such as ephedrine and pseudoephedrine. The United States and Mexico governments have acted aggressively against this trade. One consequence has been a shift to production within the United States, often using ingredients purchased from retail pharmacies. That production has been environmentally damaging for a variety of reasons having to do with the limited competence of the producers themselves and their lack of good facilities.17 Thus an unintended consequence of the tightening regulation of the international precursor market was increased health and environmental problems in the United States.18

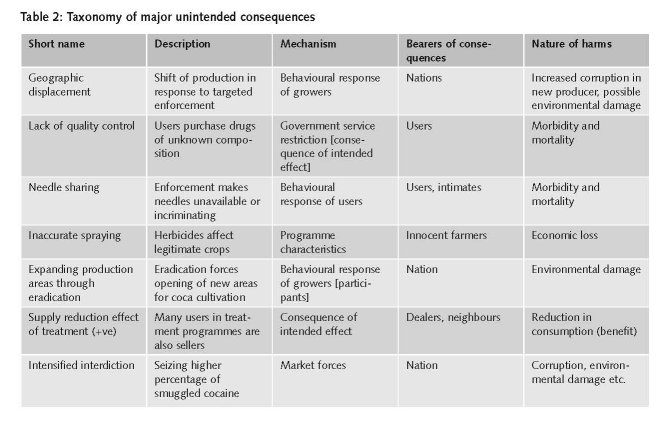

Table 2 uses this taxonomy to list some of the unintended consequences by their source (prohibition itself, a specific programme), the mechanism which induces the effect, who bears the harm and the nature of the harm itself. It aims not to be exhaustive but to suggest the variety of these effects and mechanisms. It includes one instance in which it is not a harm but a benefit that is unintended. For each entry just one mechanism is identified, though it is possible that more than one is involved.

16 Distinct from that is the dispute about the toxicity of the chemicals used for spraying. That involves a factual dispute which could be resolved through a research programme. In absence of that research the toxicity is a potential negative consequence, a “known unknown”. If it were established that the herbicide did have adverse consequences for human health and the environment, then the negative consequence could be eliminated by use of another herbicide without those effects.

17 The same phenomenon has been observed in the Netherlands as well.

18 Subsequent regulation of access to specific retail medicines in the U.S. has made domestic production more difficult and there is evidence of a decline in the number of meth labs in the U.S. See www.usdoj.gov/ndic/pubs26/26594/strat.htm#Chart3.

4 Displacement

Costa (2008) in his interesting short essay on unintended consequences focuses primarily on the concept of displacement. One instance is “substance displacement”, usually thought of as the substitution of a more powerful for a less powerful traditional form of a drug. Thus it has been asserted that in Pakistan and Thailand, the western promotion of tougher enforcement policies against opium in the 1970s led to the substitution of injected heroin instead (McCoy, 1991; Westermeyer, 1976). Heroin is preferred by dealers and users facing serious prohibitions. For users, now facing higher prices and greater risks of having the drug confiscated, heroin is desirable as a more efficient method of delivering the desired psychoactive effects and because it is more compact and thus easier to conceal. For dealers, the relative ease of concealment is the principal attraction of heroin as compared to opium. However, injected heroin poses higher risks than opium in many dimensions, including the spread of blood born diseases, a risk of fatal overdose and greater difficulty of cessation. Thus an unintended consequence of tough enforcement of prohibition is displacement to a more dangerous drug.19

Costa suggests a broader concept of substitution, which includes the shift to more concentrated forms. He gives the example of stimulants, where tough enforcement against cocaine has made that drug hard to obtain in the illicit market. This, he argues, has induced a shift of consumption to amphetamines that are relatively easy to produce. Amphetamines may be more harmful on a number of grounds; addictiveness, environmental damage from production (at least in the case of methamphetamines) and health damage from both consumption and production. Costa’s point does not depend on the greater harm of the substituted drug compared to the original but simply the adverse consequences of a shift in drugs. Analytically it is important to note this effect but without a clear statement of harm differences, it is not clear that it has policy significance.

Costa also argues that the emergence of the large criminal black market had the unintended consequence of shifting policy focus from public health to public security.20 Certainly there is evidence that enforcement dominates public expenditures on drug control, even in a country such as the Netherlands with an explicit orientation toward harm reduction (Rigter, 2006). However that does not permit assessment of whether treatment and prevention would fare better if these drugs were not prohibited. Alcohol and cigarettes are the obvious substances for comparison. Expenditures on treatment of alcohol dependence have hardly been generous and the cigarette industry was successful for decades in minimizing the public sector response to dependence on tobacco.

However assuming Costa is correct, this shift in policy focus is an indirect effect, an unintended consequence itself triggered by an unintended consequence. In this instance the first effect (the growth of criminal markets) was predictable, and indeed predicted by many; the second was less predictable. Costa’s analysis points to the breadth of the unintended effects.

In that respect his final category is particularly interesting. He notes that prohibition changes “the way we perceive and deal with the users of illicit drugs. A system appears to have been created in which those who fall into the web of addiction find themselves excluded and marginalized from the social mainstream, tainted with a moral stigma, and often unable to find treatment even when they may be motivated to want it.” (p.11) In effect, the black markets and related harms turn the social response from treatment of a disease to punishment of a crime. That is indeed an unintended, though perhaps predictable, consequence of prohibition.

Costa’s analysis again raises the need to distinguish those effects that are inherent in prohibition from those that are the consequence of the toughness with which it is enforced or the specific ways in which it is enforced. Prohibition, except at the margins such as marijuana decriminalization, is not an active area of policy decision making. The extent and form of enforcement on the other hand is very much a policy choice.

19 Cocaine may be preferred to coca under prohibition for similar reasons, though the effects of coca are so much milder that it is unlikely that, even if legal, coca would capture a large fraction of the Western market.

20 There may also be changes in non-drug policy that are intended to help lessen drug problems but which have unintended consequences for other domains. This is a variant of Costa’s “policy displacement”. For example, in the 1990s, the United States occasionally used trade concessions to Colombia (increased access to the U.S. market) as a tool to encourage the Colombian government to increase its pressure against cocaine traffickers. This is probably a rare enough phenomenon that we do not consider it further.

Consider the threat to Afghanistan’s political stability generated by the massive opium and heroin industry there, which generates perhaps as much as 50 percent of legitimate GDP (Paoli, Greenfield and Reuter, 2009). Is that a consequence simply of prohibition or of specific enforcement activities? One way to answer that is to ask what would happen if the international community lessened pressure on the government of Afghanistan to reduce poppy growing and heroin trafficking. There is little reason to believe that relaxing that pressure would make a difference to the extent of Afghanistan’s involvement in heroin production and trafficking; after all, that country by the most recent estimates accounts for over 90 percent of world opium production. The issue instead is whether the government would lose authority as the result of apparently conceding legitimacy to an activity that is known to be condemned by the international community and to cause harm to others or would gain authority by not threatening the livelihood of millions of rural Afghans. It is difficult to see a way of resolving that issue.

Another important unintended consequence associated with the heroin trade in Afghanistan and cocaine production in Colombia is the provision of finances for terrorist activities. It raises the same issue as just discussed with respect to the stability of the government of Afghanistan. To what extent is the terrorism connection a consequence of prohibition per se as opposed to tough enforcement? Historically, the Colombian example suggests the difficulty of resolving this matter. The FARC was not involved in the protection and taxation of coca growing until the mid-1990s. However with the eruption of violent conflict between the paramilitary and the cocaine traffickers, there was a large displacement of rural populations away from long-term settled areas into others where the government was weak. This provided an opportunity for the FARC to obtain a new flow of funds. Perhaps the best interpretation is that the result is highly contextual; a combination of circumstances, including policy, can lead to this outcome. The mechanism is ambiguous.

5 Positive unintended consequences

The existing literature emphasizes unintended negative effects; they are usually identified for the purpose of criticizing prohibitionist policies than for overall policy evaluation. Moreover the negative consequences are the most salient. However, there are important unintended consequences of specific interventions that are positive and worth noting for policy purposes.

For example, treatment of drug users is almost always referred to as a demand-side programme. Its benefits arise from the reduction in drug use and associated health risk behaviours, such as needle sharing. However in many countries those who sell heroin are themselves dependent users. Thus an unintended consequence of treatment is a reduction in the supply of drug selling labour; whether it is large enough to make a difference at the aggregate level depends on the specific facts of the situation.

There is a symmetric unintended consequence from the incarceration of drug dealers, since many of those locked up for dealing in heroin are also heavy users of these drugs. Thus what is regarded as a purely supply side programme has desirable demand side effects since it lowers the quantity consumed.

Tough enforcement is often seen as having a negative unintended consequence in creating barriers to treatment seeking. However in an increasing number of developed countries criminal courts have become a portal for entry into treatment.21 That may be accounted as an unintended positive effect, in that the goal of the police (as opposed to prosecutors and judges) is only dealing with the proximate problem, namely open distribution of drugs.

There is an ambiguity in how to deal with earnings from the drug trade, which clearly is an unintended consequence of prohibition. National income accounting conventions do not generally include illegal earnings in Gross Domestic Product (OECD, 2002). Indeed, drug trade earnings have historically been scrupulously ignored by institutions such as the World Bank and IMF even in countries where such earnings are manifestly important, such as Colombia in the 1980s or Tajikistan in this decade.22 Yet it is hard to deny that for farmers in Afghanistan the poppy trade has been a positive source of welfare and indeed, in the post-Taliban era, the World Bank has conducted a number of studies of the substantial economic consequences of opium production (e.g. Buddenberg and Byrd, 2006). A world in 2009 with no demand for illegal opiates would be one in which many peasants in Afghanistan were much poorer.23 That is not to argue that the net effect of prohibition is to improve the wellbeing of Afghanistan as a nation, since there are many other effects (e.g. threats to the stability and integrity of the government). It is simply to note that there are beneficiaries as well as victims of prohibition.

21 For a discussion of this in the context of the United Kingdom, see Reuter and Stevens (2007).

22 This statement is based on a review of all World Bank publications with Tajikistan in the title in the period 2000-2005 and with Colombia in the title in the period 1985-1990 and to a less comprehensive search of IMF reports.

23 Not all earnings are recorded as positive effects, since this could otherwise lead to paradoxical policies. Assume that earnings of high level dealers were included. These consist primarily of compensation for taking risks. If the supply of risk-taking labour were inelastic with respect to risks of incarceration, then a rise in the level of punishment for drug trafficking would raise GDP.

6 Concluding comments

The unintended consequences of drug policies, particularly of enforcement, have an important role in political debates about what are the appropriate ways of dealing with illicit drugs. They are large in number, diverse in type, generated by varied mechanisms and incurred by many different parties. Those critical of the current approach emphasize these consequences and often, with considerable justice, point out that we are more certain about the unintended negative effects of these policies, particularly enforcement related, than that these policies contribute much to their intended goals.

It is worth noting at this stage that in making comparisons of the existing regime with any other possible regimes, certainly involving regulated legal markets for these same drugs, that the unintended consequences of these other regimes are consistently ignored. For example, the experiences with legal alcohol, gambling and tobacco all show that the industries created work hard to undermine effective regulation of consumer health and safety (MacCoun and Reuter, 2001). This is an unintended consequence that one can confidently predict would occur if cannabis or cocaine were legalized and regulated and which ought to be weighed when assessing the desirability of alternatives.

Almost all of the unintended consequences share one important characteristic; they are unmeasured. Whether aerial eradication

in Colombia has had a substantial or only modest effect on environmental degradation in that country, to take one of the better studied, is simply a matter of conjecture. Nor can anything quantitative be said about the labour market and family consequences of Britain locking up larger numbers of drug dealers. There is hardly even a literature on how one might go about measuring these consequences in a specific time and place. Some are potentially more measurable than others; the environmental effects probably could be measured, while the child development effects are inherently elusive and very specific to countries and specific sentencing regimes.

An important consequence of this is that assessments of policy choices will not have a strong empirical base. For example, the case for expanding treatment through the criminal justice system is strengthened if it can be shown that this reduces the availability as well as the use of drugs but estimates of the supply side effects are unavailable. Similarly, an assessment of the wisdom of cracking down on street markets should take account of the potential exacerbation of violence that such crack-down generates24.

However it is important to realize that drug policy is not a purely pragmatic endeavour. Assume that an unintended but predictable consequence of aggressive actions (whether alternative livelihoods programmes or eradication) against coca production in Bolivia is that production will shift to Colombia. The international community may still choose to encourage the government of Bolivia to take such actions in order to show its resolve to make the life of those in the trade as difficult as possible (eradication) or to persuade farmers not to grow drugs (alternative livelihoods).

Analysis of these consequences serves another policy purpose as well. Even if it is impossible to estimate their scale well enough to incorporate them into a formal cost-benefit analysis, they can inform policy decisions. Obviously it would be desirable to mitigate the negative unintended consequences of interventions. This is most relevant for different forms of enforcement. Identifying the mechanism generating the undesired consequence increases the capacity for mitigation. This is already well understood with respect to reducing needle sharing by injecting drug users; e.g. police can help by not using needle possession as the basis for arrest. Making assessment of all consequences, both intended and predictably unintended, might well become part of any policy proposal. For example, when making a decision as to whether a substance should be regulated many national and international systems take into account only the direct effect of the drug on the behaviour of the user, including violence (a likely criminal effect). It might be useful to also consider the extent to which the creation of a control system would increase criminality through the growth of a black market.

Understanding which mechanisms apply can also help with other policy decisions. Take the positive effect unintended consequence of treatment discussed above, namely a reduction in the supply of drugs. In order to maximize that effect, some priority might be given to trying to persuade those most involved in drug selling to enter into treatment. It would not be the only consideration for making priority decisions but it would enter into those decisions and can only do so as a result of identifying both the consequence and mechanism generating it.

24 Even if all the victims are themselves participants in the drug trade, a democratic government should be concerned with their well-being. In fact, that violence also has some innocent victims, either bystanders or uninvolved family members.

Similarly, strategic decisions about how combat methamphetamine might take into account the environmental and health consequences of the different production configurations. Pushing the industry to large numbers of small sites, each with its own risk of explosion and contamination, may worsen the overall damage to society from methamphetamine production. Policy makers may choose investigative and prosecutorial strategies that target and sanction such high risk facilities, even if such strategies are less efficient purely as a drug control approach.

This report is exploratory. There are other possible ways of categorizing and analyzing these unintended consequences, for example by the policy area involved, the type of harm/benefit engendered or the bearers of burdens. Given the prominence of these consequences in discussions of drug policy at all levels, what is important is to move beyond mere enumeration and to develop systematic ways of studying them so that they can be incorporated both into decision making and into assessments of policy.

References

Bardach EA. practical guide for policy analysis: the eightfold path to more effective problem solving. 3rd edition. Washington, DC, CQ Press, 2008.

Braithwaite J. Crime, Shame and Reintegration. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1989.

Buddenberg D, Byrd WA (ed.). Afghanistan’s Drug Industry: Structure, Functioning, Dynamics and Implications for Counter-Narcotics Policy. New York, UNODC and World Bank, 2006.

Committee on the Prevention of HIV Infection among Injecting Drug Users in high-Risk Countries. Preventing HIV infection among injecting drug users in high risk countries: an assessment of the evidence. Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 2006.

Costa A M. Making drug control ‘fit for purpose’: Building on the UNGASS decade. Statement of the Executive Director of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2008.

Economist. The Sheriff’s stash. 24 July 2008.

Gramlich E. A Guide to Cost-Benefit Analysis. Prentice Hall, 1990.

Hirschman AO. The Rhetoric of Reaction: Perversity, Futility and Jeopardy. Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1991.

Inter-American Drug Abuse Control Commission. Environmental and Human Health Assessment of the Aerial Spray Program for Coca and Poppy Control in Colombia. Washington, DC., Organization of American States, 2005. Available: www.cicad.oas.org/en/glifosateFinalReport.pdf, last accessed 19 October 2007.

Jelsma M. Vicious Circle: The Chemical and Biological War on Drugs. Amsterdam, TransNational Institute, 2001.

Available: www.tni.org/archives/jelsma/viciouscircle-e.pdf, last accessed 16 October 2007.

Joy JE, Watson SJ, Benson JA. Marijuana and medicine: Assessing the science base. Washington, DC,. National Academy Press, 1999.

Kleiman M. Against Excess: Drug Policy for Effect. New York, Basic Books, 1992.

Leons MB, Sanabria H. (eds.) Coca, Cocaine and the Bolivian Reality. 1997.

Lenton S, Humeniuk R, Heale P, Christie P. Infringement versus conviction: the social impact of a minor cannabis offence in South Australia and Western Australia. Drug and Alcohol Review, 2000, 19(3): 257-264.

MacCoun R, Reuter P. Drug War Heresies: Learning from Other Vices, Times and Places. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2001.

McCoy AW. The Politics of Heroin: CIA Complicity in the Global Drug Trade. Brooklyn, NY, Lawrence Hill Books, 1991.

Nadelmann E. Drug prohibition in the United States: Costs, consequences, and alternatives. Science, 1989, 245: 939-947.

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development et al. Measuring the Non-Observed Economy: A Handbook. Paris, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2002.

Paoli L, Greenfield V, Reuter P. The World Heroin Market: Can Supply be Cut? New York, Oxford University Press, 2009.

Rapahel S, Johnson R. The Effect of Male Incarceration Dynamics on AIDS Infection Rates Among African-American Women and Men. Journal of Law and Economics. (Forthcoming)

Reuter P, Crawford G, Cave J. Sealing the Borders: Effects of Increased Military Efforts in Drug Interdiction. The RAND Corporation, R-3594-USDP, 1988.

Reuter P, Stevens AW. An Assessment of UK Drug Policy. UK Drug Policy Commission, 2007.

Available: www.ukdpc.org.uk/docs/UKDPC%20drug%20policy%20review.pdf

Rigter H. What drug policies cost. Drug policy expenditures in the Netherlands, 2003. Addiction, 2006, 101: 323–329.

Room R, Fischer B, Hall W, Lenton S, Reuter P. Cannabis Policy: Moving beyond the Stalemate. 2008.

Available: www.beckleyfoundation.org/pdf/BF_Cannabis_Commission_Report.pdf, last accessed 11 December 2008.

Samuels D. The California Dream. The New Yorker. 28 July 2008.

Thoumi F. Illegal Drugs, Economy and Society in the Andes. Washington, DC, Woodrow Wilson Centre, 2003.

Tonry M. Malign Neglect. New York, Oxford University Press, 1995.

Westermeyer J. The pro-heroin effects of anti-opium laws in Asia. Archives of General Psychiatry, 1976, vol. 33:1135-9.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|