Key findings

| Reports - A Report on Global Illicit Drugs Markets 1998-2007 |

Drug Abuse

Key findings

This document provides the key findings of a project assessing how the global market for drugs developed from 1998 to 2007 and describing drug policy around the globe during that period. To the extent data allows, the project assessed how much policy measures, at the national and sub-national levels, have influenced drug problems. The analysis is focused on policy relevant matters but it does not attempt to make recommendations to governments. The work was performed by the Trimbos Institute and the RAND Corporation under contract to the European Commission Directorate-General for Freedom, Justice and Security. This document is a shortened print version of the full study report. The full report includes the Main Report and six additional reports, of which abstracts have been included at the end of this document.

Operation of the world drugs market

For cocaine and heroin the cost of production and refining, as opposed to distribution, is a trivial share of the final price in Western countries, roughly one to two per cent. ATS manufacturers also receive a small share of the retail price. Only cannabis growers in rich countries receive a substantially larger share of the retail price. Smuggling across national boundaries, accounts for perhaps 10 percent of the retail price of heroin or cocaine. The vast majority of costs are accounted for by domestic distribution in the consumer country.

The overwhelming majority of those involved in the drug trade make very modest incomes. For example, the hundreds of thousands of heroin retailers in rich countries have net earnings of a few thousand Euros per annum. A few individuals in the trafficking, smuggling and wholesale sector make great fortunes but that accounts for a small share of the total income.

Production

UNODC and the United States government both produce annual estimates of production of cocaine and opium. Though the two sets of figures are inconsistent, reflecting the difficulty of making these estimates they both show that (1) production since 1998 has fluctuated around a fairly constant level for cocaine and, until 2006, also for opium. (2) production is increasingly concentrated in Afghanistan (opium) and Colombia (coca). These two drugs have always been produced by only a handful of countries but the dominant country now has an even higher share.

Cannabis is produced in over 170 countries' often indoors and in very small plots. Global production estimates are pure speculation. ATS (Amphetamine Type Stimulants) are manufactured in a few countries but still more countries than either coca or opium. The producer countries include rich ones (e.g. Netherlands for ecstasy), transition countries (the Russian Federation for amphetamines) and developing countries (e.g. Myanmar for methamphetamine). Moreover new countries enter the market on the production side in contrast to coca and opium where there is only redistribution of markets shares among the existing production countries. It is impossible to determine whether the global quantity of ATS production has increased or declined.

Consumption

The global number of users of cocaine and heroin expanded over the period; declines in some major mature markets were compensated by new user populations in countries previously little affected. For cannabis the total number of users worldwide has probably declined. For ATS no definite statement is possible.

For countries where cannabis use was common by the early 1990s (e.g. Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States) prevalence rates rose for the early part of the period, coming to a peak roughly between 1998 and 2002, and then fell substantially through 2006. For Brazil, China, India and Mexico cannabis use rates remain low relative to Western levels.

In most Western countries the number of frequent heroin users has declined through most of the last ten years while a serious epidemic of opiate use occurred in the Russian Federation and Central Asia. Iran may have the most severe opiate

onsumption problem (2.8% of the 15-64 population). There is no evidence of much increase in heroin use in China or India, both traditional consumers of opiates.

From 1998 to 2007 cocaine prevalence declined in the United States and expanded in Europe, particularly in Spain and the United Kingdom. Cocaine use is rare in any country outside of North America, Europe and a few countries in South America (notably Brazil).

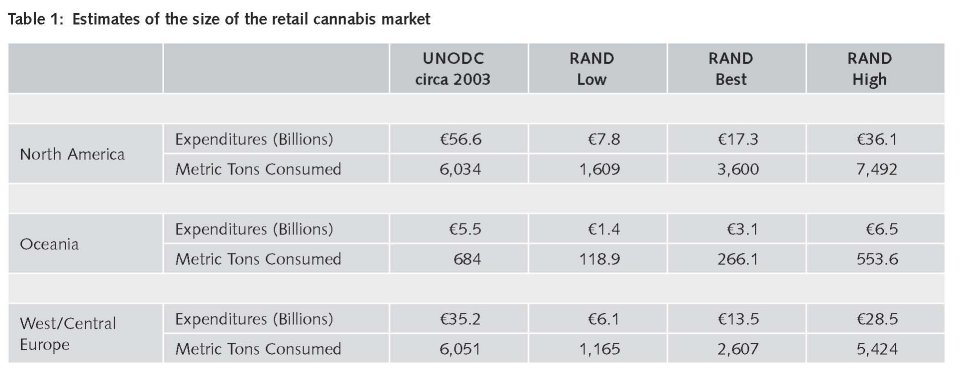

Revenues

The project developed new estimates of total revenues in 2005 and of their distribution across the various levels of distribution and production. UNODC estimated total sales revenues in 2003 as $322 billion and wholesale revenues as $94 billion. Our retail and trafficking estimates for 2005 are substantially lower. Table 1 presents UNODC and project estimates for cannabis for the major consuming regions; cannabis was estimated by UNODC as generating the highest revenues of any drug. Our best estimates of retail revenues are less than one half those of the UNODC, though there is considerable uncertainty. Our estimates of the international trade value is also substantially less than that provided by UNODC.

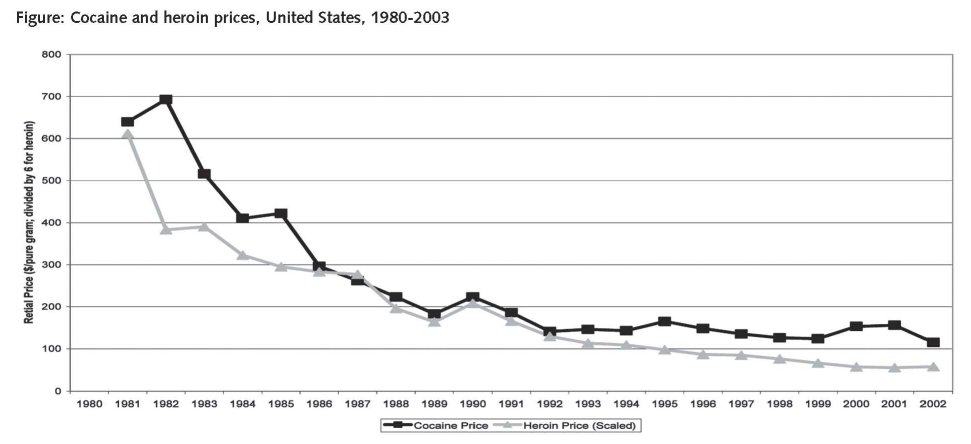

Global retail revenues have probably fallen because cocaine and heroin prices in major markets have fallen sharply. Figure 1, shows the decline in prices in the United States through 2003.

Drug-related problems

A nation's drug problem is not simply measured by the share of the population that uses some illicit drugs. It is also a function of the harms resulting, which differ among drugs and use patterns. Unfortunately very limited data were available on such major harms as the number of drug related deaths (DRDs), HIV/AIDS and drug-related crime.

In many Western countries the number of drug-related deaths has declined since about 2000. For example, in the European Union the EMCDDA estimates that the number of DRDs approximately doubled from 1990 to 2000 but then fell by about 15% to 2005. Australia experienced a decline of more than 50% between 2000 and 2005. For the major developing countries, including Brazil, China and India, no data were available on DRDs. For HIV many countries were able to reduce the incidence of new cases related to injecting drug use. There were no consistent sources of data on drug related crime for any country.

In a few developed countries there are estimates of the economic costs of drug use. The project analyzed these estimates with a goal of developing a global figure. There are so many fundamental differences in the methodology and quality of data series that the exercise was judged infeasible.

Policies

Countries use many different approaches to controlling illegal drugs. Some governments provide many services for individuals experiencing drug problems and regard the enforcement of the criminal law as a last resort, aimed primarily at protecting the public from predatory and dangerous activities related to drug selling; this list includes the Netherlands and Switzerland. Other nations see law enforcement as central to controlling drug use and related problems, with services for problematic users available only on a very limited basis; the Russian Federation and the United States are leading countries of this group. In practice, many countries have no clear strategy or policy, even if they may have a formal "Drug Strategy".

Policies appear to be converging across countries. Harm reduction (HR) has been accepted in a growing number of countries, albeit implemented in an inconsistent fashion. Some countries for whom tough enforcement had been central, notably China and Iran, now accept methadone maintenance. Globally, methadone maintenance has become much more widely available. Sweden, rhetorically opposed to Harm Reduction, has also adopted many HR programs. Even in the United States, whose federal government has continuously challenged HR in international fora, some state and municipal governments implement needle exchange. Iran, long among the very toughest in its response to violators of drug laws, now provides methadone to more than 100,000 opiate addicts.

Legal changes have reduced the criminal sanctions against drug users, both in Western countries and elsewhere. Marijuana in particular has seen reductions in legal penalties in many countries. More countries are finding ways of diverting from the criminal justice system criminal offenders whose activities are motivated by drug abuse. For example, the United Kingdom has used such programs since 2000 to massively increase the number of drug users in treatment from 100,000 in 2000 to 180,000 in 2005.

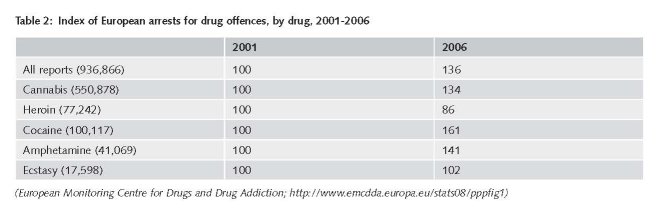

There has been simultaneously a modest toughening of enforcement against sellers in many countries. For example, the United Kingdom actively espouses harm reduction programs but has sharply increased the number of incarcerated drug sellers. Data from non-Western countries do not show a clear trend of increasingly punitive measures toward drug sellers and producers.

Prevention

The limited available evidence suggests that — in comparison to total spending on the illicit drug phenomenon - little is spent on primary prevention activities and that programs are generally of limited effectiveness. The principal funded programs are school based; some countries eschew mass media campaigns.

Though there is research evidence that effective school based programs are possible the programs that are adopted often have no demonstrated effectiveness; the US-based DARE program is the leading example. Moreover, programs are often poorly implemented. In countries facing major drug use for the first time, the prevention response has been uneven.

Treatment

There is a substantial body of evaluations of implemented treatment programs with positive outcome. However, only a few evaluations have been done outside Western countries. Opiates dominate treatment demand in most countries. Cannabis treatment demand has been rising throughout the Western world.

The total number of patients in methadone maintenance programs has grown substantially across the world and may now exceed 1 million. In some countries (e.g. Switzerland, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom) over half of the estimated opiate dependent population is now in treatment, mostly methadone maintenance.

Harm reduction

Harm reduction aims to reduce drug problems by directly targeting the adverse health- and social consequences of drug abuse; lowering the prevalence of drug use is not the goal of these interventions. Many harm reduction programs have been controversial since inception.

Most harm reduction efforts focus on injecting drug use. The canonical program involves the provision of clean needles by legally sanctioned operators (SEP: Syringe Exchange Programs). Other Harm Reduction interventions may include the provision of Naloxone to injecting drug users so that they can revive friends who have overdosed; distribution of condoms for safer sex and — in a very small number of countries — provision of safe injecting facilities.

Most Western countries have implemented many HR programs. Even amongst these countries though there is resistance to some elements of Harm Reduction. For example, heroin maintenance treatment, pioneered in Switzerland, is available on a routine basis in only five countries so far. The Russian Federation and Iran have recently begun to implement a variety of HR programs. A few Asian countries have begun implementing SEP as well.

Some countries continue to resist HR. Most are countries that have modest drug problems, such as Egypt and a group of Middle Eastern nations. HR remains essentially unknown in Latin America, where injecting drug use is not a primary concern.

Enforcement

Drug enforcement efforts take many forms.

Production controls

Efforts to control opium production have been of mixed intensity. In Burma the controlling separatist groups have cracked down on opium farmers in the Shall State. However in Afghanistan, the dominant producer, the government has opposed crop spraying, which might threaten its political stability, and has been unable to implement alternative livelihoods programs to a satisfactory level so far.

Eradication efforts against coca growing in Colombia and Peru have been consistently intense. In Bolivia relatively large sums were spent on developing legitimate economic opportunities in the principal coca growing area, the Chapare.

Because cannabis production is so dispersed around the globe, it is much more difficult to describe actions against growers. Mexico has aggressively sprayed marijuana fields. Morocco has adopted a more varied set of programs, including alternative livelihoods. Enforcement elsewhere has generally been modest. Enforcement against ATS producers is much more like investigation of traffickers or interdiction.

Interdiction

Interdiction activities (aimed at seizing drugs and smugglers in international traffic) are implemented on a large scale by a variety of countries including Iran, Mexico, the Netherlands, Turkey and the United States. The results are large seizures and the arrest of many smugglers. Global seizures, as a share of estimated global production, have risen substantially for both cocaine (from 23% in 1998 to 42% in 2007) and heroin (from 13% in 1996 to 23% in 2006).

Retail enforcement

Most drug enforcement targets retail sellers or users; retailing has the largest number of participants and is often the most visible sector. Numerous countries report active street markets for heroin while for marijuana the retail transactions often occur in private settings imbedded in social networks.

Drug specific arrest rates are not available for the developing and transitional countries. Incarceration is reserved for dug sellers in most countries. The United States incarcerates far more drug dealers per capita than any other nation, roughly 500,000 in federal, state and local facilities.

Cannabis possession accounts for most arrests in almost all Western countries. Though the numbers of persons arrested is large for some countries, even in the United States a cannabis user has less than a 1 in 3,000 risk of being arrested for any given incident of marijuana use. Almost no cannabis possession arrests produce jail sentences.

Despite the expansion of the international money laundering control system the seizures of drug related assets have been slight in all countries, relative to the estimated scale of the trade.

Policy assessment

Though the international regime consisting of the three major UN conventions and the UN institutions (CND, INCB and UNODC) constitute an important influence, policy is made primarily at the national and sub-national level and needs to be assessed against the specific problems and goals of the country, province or city.

The variety of national problems

National drug problems differ substantially. For example, Colombia is greatly harmed by drug production and trafficking; they generate high levels of violence, corruption and political instability. Consumption of drugs is modest. For Turkey, the problem is largely confined to the corruption surrounding transhipment of heroin. In contrast, European countries such as Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom have large domestic populations of dependent users of expensive drugs and minimal problems of violence, corruption or political instability related to production or trafficking. The differences in problems imply that policy has different goals.

Unintended consequences

Drug policy, particularly enforcement, has many unintended negative consequences. For example, Mexico's efforts to crackdown on drug trafficking is one factor generating a wave of horrifying killings. Incarceration for drug selling in the United States has resulted in many children deprived of the presence of their parents for extended periods.

We identified the various mechanisms that generate the unintended consequences. There are seven mechanisms that can generate unintended consequences: behavioural responses of participants (users, dealers and producers), behavioural responses of non-participants, market forces, program characteristics, program management, the inevitable effects of intended consequences and technological adaptation. The mechanisms can inform policy choices.

Drug epidemics

In examining variation across countries and over time, it is useful to think of drug use as spreading through 'epidemics'. Drug use is a learned behaviour, transmitted from one person to another. There is not literally an epidemic but the metaphor provides important statistical tools. Heroin is the drug classically associated with 'epidemics'. The model also works for cocaine powder and crack cocaine but does not seem to apply to cannabis.

This model helps assessment of changes in the number of Problem Drug Users in different nations in the same year. In the early stages of an epidemic the goal will be to prevent rapid growth in the number of new users; later, after the explosive phase is past, it will be to accelerate the numbers who quit or at least substantially reduce their consumption levels.

In many Western countries (e.g. Netherlands, Switzerland, and the United States) the population dependent on heroin is aging, as the result of a low rate of initiation, which brings in few younger users, and the long drug using careers of cocaine and heroin addicts. Treatment may reduce client drug use and has many beneficial effects for both users and society but it leads to long-term desistance by a small fraction of those who first enter.

Thus in assessing the effectiveness of drug policy at that stage of an epidemic, the number of drug users, even the number of problematic drug users, is not an appropriate indicator. Instead, governments can aim to reduce the adverse consequences of drug use by its current population of problematic drug users.

Is it possible to prevent an epidemic? Prevention is in principle the most useful. However both cocaine and heroin use have started at post-high school age, well after individuals have been exposed to prevention programs. Moreover prevention has not yet proven successful at the population level.

Treatment only indirectly effects initiation rates, since it aims at current heavy users. Harm reduction does not target either initiation or prevalence. That leaves enforcement as the one tool for preventing the start of an epidemic. There is no evidence that enforcement can prevent formation of a new market.

Production and trafficking controls

Interventions aimed at production and trafficking can affects where drugs are produced or trafficked but have not been able to reduce global output. As a consequence, the well intended efforts of one country to control production can harm other countries; thus the intensive efforts at control of production by Peru may well have worsened Colombia's problems.

The same analysis applies within a country. Large sections of Afghanistan are under the control of the Taliban, for which the drug trade is an important source of revenue. A government crack-down on opium production may shift production to the Taliban-controlled areas and enhance its funding and political base.

A rare and controversial enforcement success is the Australian "heroin drought". In late 2000, Australian heroin markets experienced an abrupt and large reduction in drug availability. Seven years later the market remains depressed. Probably this resulted from operations by the Australian and Asian governments aimed at major importers but little is known about the intervention.

Domestic enforcement

Could the higher enforcement against sellers account for the reduction in drug problems that has been observed in various countries? Tougher enforcement should reduce drug use by making drugs more expensive and/or less available. Retail prices have generally declined in Western countries, even those that intensified enforcement. There are no indications that the drugs have become more difficult to obtain.

Conclusions

We note again that this study aims to inform policy makers and not to provide recommendations.

The global drug problem clearly did not get better during the UNGASS period. For some countries (mostly rich ones) the problem declined but for others (mostly developing or transitional) it worsened, in some cases sharply and substantially. The pattern for drugs was also uneven. For example, the number of cannabis users may have declined but the sudden and substantial rise in cannabis treatment seeking suggests that consumption and harms may have gone up. On the other hand, for cocaine a roughly stable consumption was redistributed among more countries. In aggregate, given the limitations of the data, a fair judgment is that the problem became somewhat more severe.

Policy changes complicate policy assessment. We think that drug policy had no more than a marginal positive influence.

Production and trafficking controls only redistributed activities. Enforcement against local markets failed in most countries to prevent continued availability at lower price. Treatment reduced harms both of dependent users and of society without reducing the prevalence of drug use. Prevention efforts, though broad in many Western countries, were handicapped by the lack of programs of proven efficacy. Harm reduction diminished specific elements of the problem in some countries.

Enforcement of drug prohibitions has caused substantial unintended harms; many were predictable. The challenge for the next ten years will be to finwd a constructive way of building on these lessons so that the positive benefits of policy interventions are increased and the negative ones averted.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|