5 Policy assessment

| Reports - A Report on Global Illicit Drugs Markets 1998-2007 |

Drug Abuse

5 Policy assessment

5.1 Introduction

Though the international regime consisting of the three major UN drug conventions and the UN bodies (CND, INCB and

UNODC) constitute an important influence, policy is made primarily at the national and sub-national level and needs to be

assessed against the specific problems and goals of the country, province or city. Moreover, assessing a specific intervention,

such as prevention or harm reduction, requires a statement of what links that intervention to the various goals of policy.

The international regime

Reference has already been made to the three major international conventions that essentially every nation has signed. The

last of these was negotiated 20 years ago and the process of amendment is extremely cumbersome (Room et al., 2008;

Chapter VI), so they are unlikely to be changed in the near future.

Three bodies operate the international regime: (1) The International Narcotics Control Board (INCB) which has responsibility

for assuring the availability of medications that fall under the control system, notably the opioids. It also monitors compliance

with the conventions and has not hesitated in recent years to issue critical reports of national innovations (2) The Commission

on Narcotic Drugs (CND), a group of 53 nations which meets annually to set policy (3) the United Nations Office on

Drugs and Crime (UNODC) which provides technical services to national governments, particularly in developing nations,

and supports the work of the CND. It also publishes the now annual World Drug Report which has become the most cited

document on the state of the world drug problem.

It is difficult to assess the effects specifically of the international system for at least two reasons. First, the three bodies have no

policy powers outside of the convention; the INCB can administer no sanctions against nations that it judges not in compliance

with the system. Second, the resources of the system are tiny; in 2006 UNODC had a staff of about 500 worldwide and a

budget of less than $70 million.

That is not to say that the system has no effect. First, countries that have been censured by the INCB react strongly; that

suggests the censure stings. Moreover experts involved in drug policy believe that some policy changes have not been

adopted because of concerns about such censures. Second, the UNODC does offer a unique and valued service in such

activities as price monitoring in the opium and coca producing countries and its flagship publications.

However it is clear that in assessing the progress globally since UNGASS that the international bodies are at most a marginal

influence. National policy is the principal focus for assessment.

The variety of national problems

We start by noting again that nations differ substantially in the nature of their drug problems. For example, Colombia is

greatly harmed by drug production and trafficking, both of which generate high levels of violence, corruption and political

instability; consumption of drugs is modest, whether expressed as a share of the nation’s drug problems or compared to

many other countries. For Turkey, the problem is largely confined to the corruption surrounding transhipment of heroin. In

contrast, rich European countries such as Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom have large domestic populations of

dependent users of expensive drugs and minimal problems of violence, corruption or political instability related to production

or trafficking. The differences in problems imply that policy has different goals across countries.

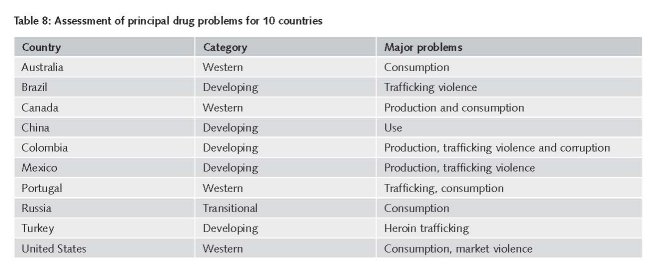

In Table 8, we present a very brief assessment of the principal drug related problems of 10 of the 18 countries that we studied,

simply to illustrate their variety. These assessments are based on the studies in Report 4 and are intended as rough judgments

rather than nuanced statements.55 Countries rarely present “pure” cases. For example, Canada does have some problems

of violence around drug trafficking, particularly biker gangs in Quebec, while Turkey does have some heroin consumption.

However these judgments do provide an indication of what problems the government in each nation is most likely to target

in its policy decisions.

5.2 Unintended consequences

A distinctive characteristic of drug policy is the prominence and variety of unintended consequences, primarily negative.

Indeed, in a much cited essay for the Commission on Narcotic Drugs meeting in 2008, the Executive Director of the UNODC

identified five broad classes of unintended consequences of prohibition as implemented that should play a role in discussions

of policy: creation of huge criminal black markets, policy displacement (from health to enforcement against those markets),

geographic displacement, substance displacement (to less controllable drugs) and displacement in the wav we perceive and

deal with the users of illicit drugs (Costa, 2008). Report 5 provides an analytic categorization of the sources of unintended

consequences that aims to extend Costa’s discussion.

It is not hard to find illustrative unintended consequences. For example bans on the possession of syringes, intended to reduce

drug use, lead to increases in needle sharing among injecting drug use and the spread of blood borne diseases such as HIV.

In some settings tough enforcement of criminal laws against the possession of cannabis, intended to reduce the number of

people who use cannabis, has large consequences in reducing the employment prospects of the arbitrarily selected set of

cannabis users who end up convicted of a criminal offense.56 These are gross statements about effects, not assessments about

whether the interventions have a positive net benefit for society.

We focus here on the unintended negative consequences of enforcement. Some are at the macro-level. Colombia’s political

stability has been affected over a long period of time by the intense efforts to control coca production, which have given a lucrative

role to the rebel movement, the FARC, in protecting coca farmers from the government. The crack-down on drug trafficking

in Mexico since 2006 is one factor generating a wave of horrifying killings that has undercut the legitimacy of governments at all

levels in Mexico. Spraying coca fields has caused considerable environmental damage not just directly but by creating a need to

plant a larger area with coca, a crop whose cultivation itself has adverse consequences for the soil. The incarceration of numerous

individuals for drug selling has resulted in many children deprived of the presence of a parent for extended periods.

There are also positive unintended consequences; these receive little attention. For example, since many heroin addicts who

enter treatment are also drug sellers, the effect of treatment is partly to reduce the supply of drug selling labour. Similarly,

many of those locked up for drug selling offenses are also drug users, so that the incarceration lowers drug demand.

The “balloon effect”, i.e. the ability of drug production to move to a new location, either within a country or across international

borders, in response to events that reduce the attractiveness of existing production areas, has been much noted as an

unintended consequence. This causes damage because the positive effects of reducing production in the initial country are in

general more than outweighed by the damage done in the new producer country. We take up its policy implications below.

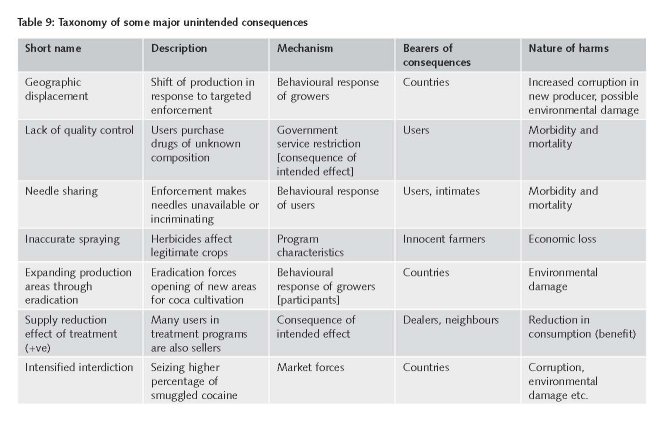

Report 5 (“The unintended consequences of drug policy”) identifies the various mechanisms that generate the unintended

consequences. It distinguishes between those consequences that arise from prohibition per se, such as the lack of quality

control, and those that are a function of the intensity and characteristics of enforcement. It identifies seven mechanisms that

can generate unintended consequences: behavioural responses of participants (users, dealers and producers), behavioural

responses of non-participants, market forces, program characteristics, program management, the inevitable effects of intended

consequences and technological adaptation. The mechanisms, presented through analysis of specific example in Table 9, are

useful for policy choices. Table 9 also highlights the variation in who bears the unintended consequences.

5.3 Drug epidemics

Another important construct for policy assessment is a simple model of the spread of drug use in a population. In examining

variation across countries and over time, it is useful to think of drug use as spreading as though there were an “epidemic” of

the behaviour. There is not literally an epidemic but it is a useful metaphor and provides important statistical tools.

The notion of a drug epidemic captures the fact that drug use is a learned behaviour, transmitted from one person to another.

Although there are individuals – drug importers and distributors – who consciously seek to create new markets for their drugs,

it is now clear that almost all first drug experiences are the result of being offered the drug by a friend or family member.

Drug use thus spreads much like a communicable disease. Users are ‘contagious’, and some of those with whom they come

into contact are willing and thus become ‘infected’.

In an epidemic, rates of initiation in a given area rise sharply as new users of a drug initiate friends and peers. At least with

heroin, cocaine, and crack, long-term addicts are not particularly ‘contagious’. They are often socially isolated from new users.

Moreover, they usually present an unappealing picture of the consequences of addiction to the specific drug. In the next

stage of the epidemic, initiation declines rapidly as the susceptible population shrinks, because there are fewer non-users to

infect, and because the drug’s reputation sours, as a result of better knowledge of its effects. The number of dependent users

stabilizes and typically gradually declines.

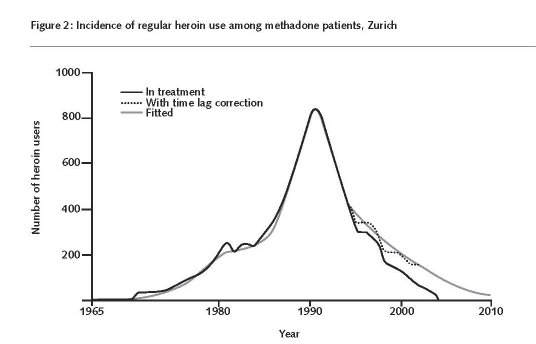

Heroin is the drug that is classically associated with ‘epidemics’ (Hunt 1974). In most Western countries there has been just

one discrete heroin epidemic. That is true for example of the Netherlands and the United States, both of which experienced

an epidemic of heroin use between the late 1960s and early 1970s; since then each has had only moderate endemic levels of

initiation. Figure 2 shows this pattern for Zurich, using heroin treatment admission reports of year of first regular use (Nordt

and Stohler, 2006).

However not all countries show this pattern for heroin. For example in the United Kingdom there was an increase in heroin

initiation rates from about 1975 to 2000 (Reuter and Stevens, 2007).

The model also works for cocaine powder and crack cocaine in the United States (Caulkins et al. 2004). It has not been fitted

to the spread of cocaine in European countries; the required data are not available in those countries. Nor has it yet been fit

to the distribution of methamphetamine in the United States.

The model does not seem to apply to cannabis, in part because the adverse effects of cannabis use appear modest to users

(Hall and Pacula, 2003). It is not plausible for drugs that are not dependency creating, such as ecstasy.

It is however useful to keep this model in mind when considering changes in the number of Problem Drug Users in different

nations in the same year. One country might be early in its epidemic, with the “natural” change from the past year being a

substantial increase in new initiates; simply preventing an increase in the number of current users would be a major success.

Another nation may be at the end of its epidemic, with the undisturbed trajectory being a modest decline from the previous

year; an observed decline might then not indicate any particular policy success.

An important characteristic of a drug epidemic is that the distribution of drug use changes over its course. In the early stages

of the epidemic there are many occasional users of drugs and few who are yet dependent. As the epidemic of new use comes

to an end, many light users desist, while a few go on to become frequent and dependent users. Thus the numbers of drug

users may decrease even as total quantity consumed goes up. This is precisely the finding of Everingham and Rydell (1994)

with respect to cocaine in the United States. The number of cocaine users declined sharply after about 1982, but because of

the contemporaneous growth in the number of frequent users, total consumption continued to rise until 1988 at least, and

declined only slowly after that.57

This has two consequences for assessing policy toward cocaine and heroin. First, what can be accomplished through policy is

a function of where a nation is in terms of the epidemic it is experiencing. Second, what policy interventions are likely to be

effective will also depend on the epidemic stage.

In the early stages the goal will be to prevent rapid growth in the number of new users; later, after the explosive phase is

past, it will be to accelerate the numbers who quit or at least substantially reduce their consumption levels. Caulkins and

collaborators in a long series of papers (e.g. Tragler, Caulkins and Feichtinger, 2001), have explored the policy implications of

these factors on the optimal choice of policy instruments.

In many Western countries the population dependent on heroin is aging. For example, the same aging pattern can be found in

the Netherlands, Switzerland and the United States, despite different policy stances.58 In the United States it can be observed

very clearly in the cocaine population as well. It represents the consequences of a combination of a low rate of initiation,

which brings in few younger users, and the long drug using careers of those persons dependent on cocaine and heroin.59

Treatment may reduce client drug use and has many beneficial effects for both users and society but it leads to long-term

desistance by a small fraction of those who first enter.

Thus in assessing the effectiveness of drug policy at that stage of an epidemic, the number of drug users, even the number

of problematic drug users, is not an appropriate indicator. Instead, governments can aim to reduce the adverse consequences

of drug use by its current population of problematic drug users. Thus cocaine, there is then a sharp difference between the

situation of the United States on the one hand and, say, Portugal on the other. Portugal may still be in the explosive stage

of the epidemic and might reasonably aim at reducing the number of new problematic users. That should probably only a

secondary goal for the United States.

Is it possible to prevent an epidemic from starting? The first problem is that of detecting it, since surveillance systems are

largely backward looking. The Drug Abuse Warning Network, set up in the United States in the early 1970s, was an attempt

to use the appearance of Emergency Room patients with problems related to their drug use to rapidly detect the arrival of

new drugs and thus allow for preventative policies. There has been no evaluation of how well it has worked in that respect

but it does not seem to have provided valuable early warning for example of the spread of methamphetamine from its West

Coast base in the 1990s. Moreover not all drugs with great potential for harm will manifest that harm in the early phases,

defeating an Emergency Room based system. Other systems may be possible but have not yet been implemented.

We observe only those outbreaks of drug use that actually occur and not those that might have been, so analysis of past

experiences will not be informative as to what actions might prevent an epidemic from occurring once it has begun. Instead

one can only consider the plausibility of the various instruments that are available. Prevention is in principle the most useful;

if youth can be persuaded that psychoactive substances are dangerous, then the potential for a new epidemic is limited.

However both cocaine and heroin use have started at post-high school age, well after individuals have been exposed to

prevention programs. Given the lack of evidence at the population level that prevention can substantially reduce the number

of initiates among 12-17 year olds, there seems little potential for preventing a new epidemic in, say, 18-24 year olds.

Treatment can have only indirect effects on initiation rates, since it is an intervention aimed at those who have already become

heavily involved with the drug.60 Harm reduction does not target either initiation or prevalence. That leaves enforcement as

the one tool for preventing the start of an epidemic. Enforcement is not generic but rather aims at specific drug markets.

Hence it is likely to lag in its effects for a new drug; moreover new drugs are often distributed through social networks rather

than through markets and thus are particularly hard to police.

5.4 Production and trafficking controls

There is little doubt that interventions aimed at production can affect where drugs are produced. We noted above the

changing location of coca growing within the Andean region that are plausibly related to the actions of the governments of

Bolivia, Colombia and Peru. Changes in the location of ATS production over the last decade may also reflect such actions.

What is far less clear is that government interventions have been able to reduce total output, as opposed to where and in

what way the drugs are produced. This is the essence of the claimed “balloon effect”, frequently noted by critics of the

existing control system (e.g. Nadelmann, 1988) as well as by Costa (2008). What has not been developed is the implications

of that balloon effect for policies at the national and international level. The well intended efforts of one nation to control

production can harm other nations; thus the aggressive efforts at control of production by Peru may well have worsened

Colombia’s problems.

Even within a country, the same analysis can provide useful conclusions. Large sections of Afghanistan are under the control

of the Taliban, for which the drug trade is an important source of revenue. If the government cracks down on opium production

in the territories it controls, it may shift production to the Taliban-controlled areas and thus enhance the funding and

political base of the guerrillas. This presents a serious dilemma for the government, since ignoring opium growing undercuts

its authority, in part by providing an independent source of finance for local warlords who may challenge the government.

Exactly the same argument can be made about efforts to control international trafficking. There are typically many paths by

which drugs can travel from their production point to their final market. If tough enforcement makes smuggling along one

route difficult, traffickers may try another.

In recent years this kind of interaction has been conspicuous with respect to trafficking of cocaine. We illustrate the phenomenon

by taking advantage of an unusually detailed analysis of a successful control effort by the Dutch government.

The Netherlands Antilles is conveniently located for Colombian traffickers shipping to Europe; it has many direct flights to

one of Europe’s busiest airports, Schiphol in Amsterdam. In response to evidence of growing trafficking of cocaine primarily from

Curacao to the Amsterdam airport, the Netherlands government implemented a 100 percent search policy for airline passengers

in Curacao in March 2004 (World Bank and UNODC, 2007). Whereas cocaine seizures in the Netherlands Antilles had not

exceeded 1.3 tons before 2003, in 2004 they reached 9 tons, a remarkable figure for a jurisdiction with fewer than 200,000

inhabitants; the United States seizes only about 150 tons. Seizures of cocaine at Schiphol airport have fallen sharply.

Very probably as a consequence new trafficking routes have opened up from South America to Europe via West Africa

(EMCDDA, 2008).61 For example, the nation of Guinea-Bissau is impoverished and small; it has no military or police capacity

to deal with smugglers and the government is easily corrupted. Smugglers have started using landing strips there for large

shipments. In 2007 there was one seizure of three quarters of a ton and it is believed that an even larger quantity from that

shipment made it out of the country (Sullivan, 2008).

Ghana, a larger nation but one also with fragile institutions, has also seen a sudden influx of cocaine traffickers; in 2005 Accra

accounted for more seized cocaine at London’s Heathrow than did any other city. There are now regular reports of multi-kilo

seizures of the drug either in Ghana itself or at airports after flights from Ghana.

Assuming that Ghana and Guinea-Bissau are serving as trafficking nations at least in part because of the effective crack-down

on an existing route through Curacao, is the world better off as a result of the crack-down? Certainly the Netherlands has

helped itself and one can not be critical of a country making a strong effort to minimize its involvement in the drug trade.

However one can reasonably ask whether in making these decisions, the Netherlands should take into account the likely

effects of their actions on other, more vulnerable countries. We raise this not as a criticism of any government but to point

to an interdependency that has not been explicitly recognized in discussions of international enforcement.

More generally, though, it appears that trafficking control efforts have had little effect in the last ten years. Iran remains a

major transhipment country, despite its long-standing commitment of large resources to interdiction of opiates from Afghanistan

and its willingness to administer tough punishment on convicted smugglers. Mexico in recent years has also made intense

efforts to control smuggling of cocaine from Colombia to the United States. Though there is some indication of a reduction of

export levels in 2007, perhaps reflecting the intensified violence in the market, there is good reason to see this as a temporary

respite. This was the pattern when the flow of cocaine from Colombia was interrupted during the battle between the Medellin

traffickers and Colombian government took place in 1989-1990; the flow resumed at comparable rates after the conflict

subsided with government victory and the re-ordering of the cocaine trade. United States destined cocaine still seems to flow

primarily through Mexico, even two years after the government’s crack-down.

For Mexico corruption may have been a major factor explaining the ineffectiveness of the effort to reduce trans-shipment.

Even in late 2008, two years after President Calderon made the effort against the traffickers a prominent part of his administration’s

agenda, there have been revelations of corruption at the very highest levels of the drug enforcement system (e.g.,

Stevenson, 2008). Too little is known about Iranian enforcement to make statements about the role of corruption in its lack

of success in shifting the trans-shipment traffic to Europe to other routes).

A rare and controversial exception to the failure of interdiction is the Australian “heroin drought”. In late 2000, Australian

heroin markets experienced an abrupt and large reduction in drug availability (Weatherburn, Jone, Freeman and Makkai,

2003). Though there has been some recovery in availability in the following seven years, this event appears to have had

long-term effects. The most likely cause of this interruption is an operation by the Australian authorities (together with

agencies of other governments in Asia) aimed at the small number of major heroin shippers, in particular a seizure and set

of arrests in Fiji (Degenhardt, Reuter, Collins and Hall, 2005). While Degenhardt et al. argue against other interpretations

that give a role to treatment or supply side shifts in the Golden Triangle, so little is known about the specific cause of this

drying up of the heroin market that one can say little more than that perhaps effective interdiction against an isolated

market is possible.

5.5 Domestic enforcement

We noted earlier that there has been a decline in the drug problems of some nations that have been particularly damaged

by drugs in the past and that there has also been an increase in the stringency of enforcement against sellers. Could the

more aggressive enforcement against traffickers and retailers account for the reduction in problems?

That question cannot be answered in a rigorous fashion, for a variety of methodological reasons and because of the

lack of data on enforcement intensity and outcomes.62 However the available evidence is roughly inconsistent with the

hypothesis.

Tougher enforcement should reduce drug use by making drugs more expensive and/or less available. The underlying model

is that the risk of arrest, imprisonment, seizure of drugs, money and assets are all costs to producers and distributors (Reuter

and Kalian, 1986). The higher those risks, the more suppliers will charge for the service. The one published effort, in the

United States, to model rigorously the effects of increased enforcement found that a tripling of cocaine selling arrests had

led to an increase of between 5 and 15% in the price of cocaine, a small return for such a large increase (Kuziemko and

Levitt, 2004). [Bushway et al.]

We have already noted that retail prices have generally declined in Western countries, including those that increased the

stringency of their enforcement against sellers, such as the United Kingdom and the United States There are no indications

that the drugs have become more difficult to obtain. Indeed, survey data such as Monitoring the Future, show very little

evidence of changes in perceived availability (Johnston et al., 2007).

5.6 Methodological issues

Drug problems and drug policy may attract considerable policy and political attention but that has not been matched

by large scale data collection and analysis. There remains a dearth of data sets or indicators for comparing how one

nation’s drug problem compares to that of other nations; for describing how a nation’s drug problem has changed over

time; and for assessing how drug policies contributed to observed changes in national drug problems over time. Report 6

(“Methodological problems confronting cross-national assessments of drug problems and policies”) describes some

of the major data limitations facing assessments of drug problems (demand, supply, harms) and policies; it focused

particularly on challenges to cross-national comparisons. It identifies both conceptual and empirical elements of those

limitations.

Conceptual challenges include inconsistencies in definition and operationalisation of concepts. A well-known conceptual

difficulty is the lack of consensus in defining problematic drug use. Another example is the very concept of “drug” itself. In

English speaking countries this concept covers both illicit drugs and medical prescription drugs; in other countries (e.g. the

Netherlands) the term drug is reserved for illicit drugs. This difference has large consequences for the registration of drugrelated

deaths. A third example is the question “What is drug-related crime?” The relationship between drugs and crime is

complex. It has for example been noted that this relationship can be dynamic and may vary over time (EMCDDA, 2007a).

Even simple differences across countries can create problems of comparison. For example, in Britain the household survey

data is reported for ages 16-59, whereas in Australia it covers all persons over the age of 14. Though this would not present

a problem for an analyst with access to all the data, the published data do not allow for exact comparisons of prevalence

between the two nations, except for specific age groups. Some countries conduct in-person interviews, while others use

telephones for interviews; the latter is known to result in lower prevalence rates. The cumulative effect of these differences

is to make the comparative analysis very approximate.

55 Western refers both to a cultural identity and to a high level of wealth. Some nations could clearly be placed in more than one category. For

example, Portugal having emerged from fifty years of military rule and isolation in the mid-1970s might be regarded in 1998 as still in the

process of transition to a Western nation with established democratic institutions and a predominantly middle class populace.

56 This was an important element of the argument for removing criminal penalties for simple possession of marijuana in Western Australia in 2002.

See, for example, Lenton et al. (2000).

57 The consumption increase also reflected the decline in price that probably led to an increase in annual consumption per dependent user.

58 The most explicit modeling of this phenomenon is Nordt and Stohler (2006) using treatment entry data for Zurich.

59 The length of heroin using careers is best documented in a remarkable 33 year follow-up of a sample of dependent users recruited in the 1960s,

many of whom were still using 30 years later (Hser et al, 2001).

60 As already mentioned , treatment may reduce the supply of drug selling labor since many of those treated for heroin or cocaine dependence are

also drug distributors.

61 In response to the emergence of this new route, seven European nations in the middle of 2007 set up a new entity named MAOC-N (Maritime

Analysis and Operations Center-Narcotics). By the end of 2008, MAOC-N had helped in the seizure of 40 tons of cocaine http://www.guardian.

co.uk/world/2009/feb/09/drugs-patrol-cocaine-seizure [accessed 15 February 2009].

62 The fundamental problem is the lack of sub-national measures of the size of drug markets that would allow the estimation of the intensity of

enforcement. Is an increase in drug seller arrests or incarceration the consequence of more drug sellers or more effective enforcement? Without

being able to measure variation in enforcement intensity within a country over time, the potential empirical analyses are weak.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|