Although the Corsican underworld's wartime alliances were to have important consequences for the postwar heroin traffic and laid the foundation for Marseille's future criminal dynasty, the end of the German occupation generally meant hard times for the Marseille

milieu. For over twenty years Carbone and Spirito had dominated the underworld, pioneering new forms of criminal activity, providing leadership and discipline, and most importantly, political alliances. Now they were gone, and none of the surviving syndicate bosses had as yet acquired the power or privilege to take on their mantle.To add to its problems, the milieu's traditional enemies, the Communist and Socialist parties, remained firmly allied until mid 1946, thus denying a conservative-underworld alliance any chance of acquiring political power. In the first municipal elections of April 1945, a leftwing coalition swept Socialist party leader Gaston Defferre into the mayor's office. Splitting with the Socialists in 1946, the Communist party mounted a successful independent effort- and elected its candidate mayor in November. (19)

Moreover, a new police unit, the CRS (Compagnies Republicaines de Securite) had become the bane of the Marseille underworld. Formed during the liberation struggles of August 1944, when most of the municipal police force (who had been notorious collaborators) disappeared, (20) the CRS was assigned the task of restoring public order, tracking down collaborators, restricting smuggling, and curbing black market activities. A high percentage of its officers was recruited from the Communist Resistance movement, and they performed their duties much too effectively for the comfort of the milieu. (21)

But the beginning of the milieu's rise to power was not long in coming.

In the fall of 1947 a month of bloody street fighting, electoral reverses, and the clandestine intervention of the CIA toppled the Communist party from power and brought about a permanent realignment of political power in Marseille. When the strikes and rioting finally came to an end, the Socialists had severed their contacts with the Communists, a Socialist-underworld alliance was in control of Marseille politics, and the Guerini brothers had emerged as the unchallenged "peacemakers" of the Marseille milieu. For the next twenty years their word would be law in the Marseille underworld.

The confrontation began innocently enough with the municipal elections of October 19 and 26, 1947. On the national level, Gen. Charles de Gaulle's new antiCommunist party (Rassemblement du Peuple Francais, RPF) scored substantial electoral successes throughout France. In Marseille, the revitalized Conservatives won enough seats on the municipal council to unseat the Communist mayor and elect a Conservative, Michel Carlini. One of Mayor Carlini's first official acts was to raise the municipal tram fares: a seemingly uncontroversial move entirely justified by growing fiscal deficits. However, this edict had unforeseen consequences.

More than two years after the end of the war, Marseille was still digging itself out from the rubble left by the Allied bombing. Unemployment was high, wages were low; the black market was king, and a severe shortage of the most basic commodities lent an air of desperation to morning shoppers. (22) The tramways were the city's lifeline, and the increased fare pinched pocketbooks and provoked bitter outrage. The Communist-Socialist labor coalition (Confederation Generale du Travail, CGT) responded with a militant boycott of the tramways. Any motorman daring to take a tram into the streets was met with barricades and a shower of rocks from the angry populace. (23)

Marseille's working class was not alone in its misery, Across the length and breadth of France, blue-collar workers were suffering through the hard times of a painful postwar economic recovery, Workers were putting in long hours, boosting production and being paid little for their efforts. Prodded by their American advisers, successive French cabinets held down wages in order to speed economic recovery. By 1947 industrial production was practically restored to its prewar level, but the average Parisian skilled worker was earning only 65 percent of what he had made during the depths of the depression. (24) He was literally hungry as well: food prices had skyrocketed, and the average worker was eating 18 percent less than he had in 1938, And even though their wages could barely cover their food expenditures, workers were forced to shoulder the bulk of the national tax burden. The tax system was so inequitable that the prestigious Parisian daily Le Monde labeled it "more iniquitous than that which provoked the French Revolution. (25)

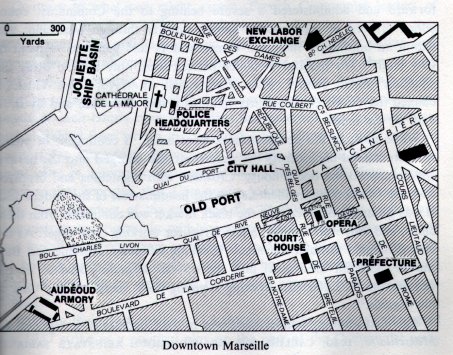

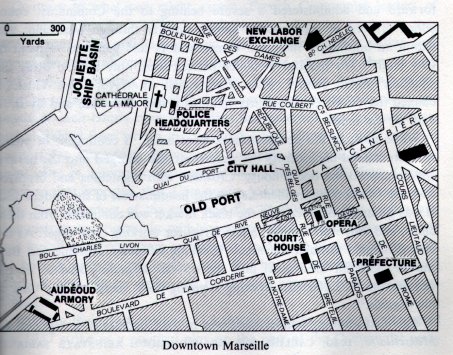

In Marseille, throughout early November, ugly incidents heated political tensions in the wake of the tramways boycott, culminating in the escalating violence of November 12. That fateful day began with a demonstration of angry workers in the morning, saw a beating of Communist councilors at the city council meeting in the afternoon, and ended with a murder in the early evening. (26) Early that morning, several thousand workers had gathered in front of the courthouse to demand the release of four young sheet metal workers who had been arrested for attacking a tram. As the police led two of them toward the hall for their trial, the crowd rushed the officers and the men escaped. Emboldened by their initial success, the crowd continued to try to break through police cordons for several hours, demanding that the charges against the workmen be dropped. Responding to the determined mood of the crowd, the court was hastily convened, and at about four in the afternoon the charges were reduced to the equivalent of a misdemeanor. The demonstrators were just preparing to disband when an unknown worker arrived to announce, "Everybody to City Hall. They are beating our comrades. (27)

The assault had occurred in the course of a regular meeting of the municipal council, when Communist councilors raised the issue of the tramway fares. The discussions became overly heated, and some of the mayor's well-muscled supporters (members of the Guerini gang) rushed forward and administered a severe beating to the Communist councilors.(28) Word of the beatings spread quickly through Marseille, and within an hour forty thousand demonstrators had gathered in front of City Hal 1. (29) The handful of police present were only able to bring the situation under control when Communist ex-Mayor Jean Cristofol calmed the crowd. Within thirty minutes it had dispersed, and by 6:30 P.m. all was quiet.

While most of the demonstrators went home, a contingent of young workers rushed back across the waterfront and charged into the narrow streets around the opera house. Crowded with nightclubs and brothels, the area was commonly identified as the headquarters of the underworld. It was generally believed that the black market was controlled from these clubs, and they were deemed a just target for working class anger. As the crowd roamed through the streets breaking windows, Antoine and Barthelemy Guarani fired guns into the crowd, wounding several of the demonstrators. Later that evening a young sheet metal worker died of his wounds. (30)

The next morning banner headlines in the Communist newspaper, La' Marseillaise, read, CARLINI AND DE VERNEJOUL REINSTATE SABIANI'S METHODS IN THE MAYOR'S OFFICE OF MARSEILLE. The paper reported that an investigation had disclosed it was Guerini men who had attacked the municipal councilors.(31) This charge was not seriously rebutted in the Socialist paper, Le Provencal, or the Gaullist Meridional In a court hearing on November 16, two police officers testified seeing the Guerinis shooting into the crowd. At the same hearing one of the younger Guerini brothers admitted that Antoine and Barthelemy had been in the area at the time of the shooting. But four days later the police mysteriously retracted their testimony, and on December 10 all charges against the Guerinis were dropped. (32) The morning after the shooting, November 13, the local labor confederation called a general strike, and the city came to a standstill.

The strike was universal throughout France. Marseille workers had reached the breaking point at about the same time as their comrades in the rest of France. Spontaneous wildcat strikes erupted in factories, mines, and railway yards throughout the country. (33) As militant workers took to the streets, demonstrating for fair wages and lower prices, the Communist party leadership was reluctantly forced to take action. On November 14, the day after Marseille's unions went on strike, the leftist labor confederation, CGT, called for a nationwide general strike.

Contrary to what one might-expect, French Communist leaders of this era were hardly wild-eyed revolutionaries. For the most part they were conservative middle-aged men who had served their nation well during the wartime resistance and now wanted, above all else, to take part in the governance of their country. Their skillful leadership of the wartime resistance had earned them the respect of the working class, and thanks to their efforts French unionists had accepted low postwar wages and abstained from strikes in 1945 and 1946. However, their repeated support for Draconian government austerity measures began to cost them votes in union elections, and in mid 1946 one U.S. State Department analyst reported that Communist leaders "could no longer hold back the discontent of the rank and file." (34) When wildcat strikes and demonstrations erupted in mid-November 1947, the Communist party was forced to support them or forfeit its leadership of the working class. At best its support was halfhearted. But by late November, 3 million workers were out on strike and the French economy was almost paralyzed.

Ignoring their own analysts, U.S. foreign policy planners interpreted the 1947 strike as a political ploy on the part of the Communist party and "feared" that it was a prelude to a "takeover of the government." (35) The reason for this blindness was simple: by mid 1947 the cold war had frozen over and all political events were seen in terms of "the world wide ideological clash between Eastern Communism and Western Democracy." Apprehensive over Soviet gains in the eastern Mediterranean, and the growth of Communist parties in western Europe, the Truman administration drew up the multibillion-dollar European Recovery Plan in May (known popularly as the Marshall Plan) and established the CIA in September. (36) Determined to save France from an imminent Communist coup, the CIA moved in to help break up the strike, choosing the Socialist party as its nightstick.

On the surface it may have seemed a bit out of character for the CIA to be backing anything so far left as a Socialist party. However, there were only three major political parties in France-Socialist, Communist, and Gaullist-and by a simple process of elimination the CIA wound up bedding down with the Socialists. While General de Gaulle was far too independent for American tastes, Socialist leaders were rapidly losing political ground to the Communists and were only too willing to collaborate with the CIA.

Writing in the Saturday Evening Post in 1967, the former director of the CIA's international organizations division, Thomas W. Braden, explained the Agency's strategy of using leftists to fight leftists:

It was personified by Jay Lovestone, assistant to David Dubinsky in the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union.

Once Chief of the Communist Party in the United States, Lovestone had an enormous grasp of foreign-intelligence operations. In 1947 the Communist Confederation Generale du Travail led a strike in Paris which came very close to paralyzing the French economy. A takeover of the government was feared.

Into this crisis stepped Lovestone and his assistant, Irving Brown. With funds from Dubinsky's union, they organized Force Ouvriere, a non-Communist union. When they ran Out of money they appealed to the CIA. Thus began the secret subsidy of free trade unions which soon spread to Italy. Without that Subsidy, postwar history might have gone very differently. (37)

Shortly after the general strike began, the Socialist faction split off from the CGT (Confederation Generale du Travail) and formed a separate union, Force Ouvriere, with CIA funds. CIA payments on the order of $1 million a year guaranteed the Socialist party a strong electoral base in the labor movement, (38) and gave its leaders the political strength to lead the attack on striking workers. While Marseille Socialist leader Gaston Defferre called for an anti-Communist crusade from the floor of the National Assembly and in the columns of Le Provencal, (39) Socialist Minister of the Interior Jules Moch directed brutal police actions against striking workers. (40) With the advice and cooperation of the U.S. military attache in Paris, Moch requested the call-up of 80,000 reservists and mobilized 200,000 troops to battle the strikers. Faced with this overwhelming force, the CGT called off the strike on December 9, after less than a month on the picket lines. (41)

The bloodiest battleground of the general strike had not been in Paris, as Braden indicates, but in Marseille. Victory in Marseille was essential for U.S. foreign policy for a number of reasons. As one of the most important international ports in France, Marseille was a vital beachhead for Marshall Plan exports to Europe. Continued Communist control of its docks would threaten the efficiency of the Marshall Plan and any future aid programs. As the second largest city in France, continued Communist domination of the Marseille electorate would increase the chance that the Communist party might win enough votes to form a national government. (The Communist party already controlled 28 percent of the vote and was the largest party in France.)

The growing split between Marseille's Communist and Socialist parties and Defferre's willingness to serve American interests had already been revealed in National Assembly debates over the bloody incidents on November 12 in Marseille. Instead of criticizing the Guerinis for beating the municipal councilors and murdering the sheet metal worker, Socialist leader Gaston Defferre chose to attack the Communists.

The American and English flags which were hanging from city hall were slashed by Communist hordes.... We have proof of what the Communists are capable: I trust that the government will take note of the consequences.

The Socialist Party deplores these incidents, but it will not tolerate that those who try to pass here as representatives will be able to defy the law. (42)

Several days later Communist deputy Jean Cristofol rebutted Defferre's accusations, charging that the Guerinis' gangsters were in the employ of both Gaullist and Socialist parties in Marseille. When Defferre rose to deny even knowing M. Guerini, another Communist deputy reminded him that a Guerini cousin was the editor of Defferre's newspaper, Le Provencal Then Cristofol took over to reveal some disturbing signs of the Marseille milieu's revival: underworld collaborators were being paroled from prison and government officials were allowing milieu nightclubs to reopen, among them the Guerinis' Parakeet Club. (The clubs had been closed in June 1947 by order of Cristofol himself, then town mayor.) (43)

The Socialists' first step in breaking Marseille's strike was purging suspected Communist supporters from the CRS police units. Once this was accomplished these units could easily be ordered to use violent tactics against the striking workers. Thus, although official reports had nothing but praise for the cool professionalism of these officers (44) Socialist Mayor Gaston Defferre unjustly accused them of having sided with the demonstrators during the rioting of November 12. (45) After Socialist cadres drew up a list of suspected CRS Communists, Mayor Defferre passed it along to Socialist Minister Jules Moch, who ordered the blacklisted officers fired. (46) (This action by the Socialists was certainly appreciated by the hard-pressed Corsican syndicates as well. In sharp contrast to the regular police, CRS units had been cracking down on the milieu's smuggling and black market activities.) (47) Once these Communist officers had been purged, CRS units started attacking picket lines with unrestrained violence. (48)

But it would take more than ordinary police repression to break the determination of Marseille's eighty thousand striking workers. If the U.S. was to have its victory in Marseille it would have to fight for it. And the CIA proceeded to do just that,

Through their contacts with the Socialist party, the CIA had sent agents and a psychological warfare team to Marseille, where they dealt directly with Corsican syndicate leaders through the Guerini brothers. The CIA's operatives supplied arms and money to Corsican gangs for assaults on Communist picket lines and harassment of the important union officials. During the month-long strike the CIA's gangsters and the purged CRS police units murdered a number of striking workers and mauled the picket lines. Finally, the CIA psychological warfare team prepared pamphlets, radio broadcasts, and posters aimed at discouraging workers from continuing the strike. (49) Some of the psy-war team's maneuvers were inspired: at one point the American government threatened to ship sixty-five thousand sacks of flour meant for the hungry city back to the United States unless the dockers unloaded them immediately. (50) The pressure of violence and hunger was too great, and on December 9 Marseille's workers abandoned the strike, along with their fellow workers in the rest of France. There were some ironic finishing touches. On Christmas Eve of 1947, eighty-seven boxcars arrived at the Marseille train station carrying flour, milk, sugar, and fruit as "gifts from the American people" amidst the cheers of hundreds of schoolchildren waving tiny American flags. (51)

The Guerinis gained enough power and status from their role in smashing the 1947 strike to emerge as the new leaders of the Corsican underworld. But while the CIA was instrumental in restoring the Corsican underworld's political power, it was not until the 1950 dock strike that the Guerinis gained enough power to take control of the Marseille waterfront. This combination of political influence and control of the docks created the perfect environmental conditions for the growth of Marseille's heroin laboratoriesfortuitously at exactly the same time that Mafia boss Lucky Luciano was seeking an alternate source of heroin supply.

The same austere economic conditions that had sparked the 1947 strike also produced the 1950 shutdown. Conditions for the workers had not improved in the intervening three years and, if anything, had grown worse. Marseille, with its tradition of working class militancy, had even more reason for striking. Marseille was France's "Gateway to the Orient," through which material (particularly American munitions and supplies) was transported to the French Expeditionary Corps fighting in Indochina. The Indochina War was about as unpopular with the French people then as the Vietnam War is with so many of the American people today. And Ho Chi Minh had helped to found the French Communist party and was a popular hero in France among the leftist working class members, especially in Marseille with its many resident Indochinese. (52) In January, Marseille dock workers began a selective boycott of those freighters carrying supplies to the war zone. And on February 3 the CGT convened a meeting of Marseille dock workers at which a declaration was issued demanding "the return of the Expeditionary Corps from Indochina to put an end to the war in Vietnam," and urging "all unions to launch the most effective actions possible against the war in Vietnam." The movement of arms shipments to Indochina was "paralyzed." (53) Although the Atlantic ports joined in the embargo in early February, they were not as effective or as important as the Marseille strike. (54) By mid February, the shutdown had spread to the metal industries, (55) the mines, and the railways. But most of the strikes were halfhearted. On February 18 the Paris newspaper Combat reported that

Marseille was once again the hard core; 70 percent of Marseille's workers supported the strike compared to only 2 percent in Bordeaux, 20 percent in Toulouse, and 20 percent in Nice. (56) Once more Marseille's working class militancy called for special methods, and the CIA's Thomas Braden later recalled how he dealt with the problem.

"On the desk in front of me as I write these lines is a creased and faded yellow paper. It bears the following inscription in pencil:

"Received from Warren G. Haskins, $15,000 (signed) Norris A. Grambo."

I went in search of this paper on the day the newspapers disclosed the "scandal" of the Central Intelligence Agency's connections with American students and labor leaders. It was a wistful search, and when it ended, I found myself feeling sad.

For I was Warren G. Haskins. Norris A. Grambo was Irving Brown, of the American Federation of Labor. The $15,000 was from the vaults of the CIA, and the yellow paper is the last memento I possess of a vast and secret operation....

It was my idea to give $15,000 to Irving Brown. He needed it to pay off his strong-arm squads in the Mediterranean ports, so that American supplies could be unloaded against the opposition of Communist dock workers." (57)

With the CIA's financial backing, Brown used his contacts with the underworld and a "rugged, fiery Corsican" named Pierre Ferri-Pisani to recruit an elite criminal terror squad to work the docks. Surrounded by his gangster hirelings, Ferri-Pisani stormed into local Communist headquarters and threatened to make the party's leadership "pay personally" for the continuing boycott. And, as Time magazine noted with great satisfaction, "The first Communist who tried to fire Ferri-Pisani's men was chucked into the harbor." (58)

In addition, the Guerinis' gangsters were assigned the job of pummeling Communist picket lines to allow troops and scabs onto the docks, where they could begin loading munitions and supplies. By March 13 government officials were able to announce that, despite a continuing boycott by Communist workers, 900 dockers and supplementary troops had restored normal operations on the Marseille waterfront. (59) Although sporadic boycotts continued until mid April, Marseille was now subdued and the strike was essentially over. (60)

But there were unforeseen consequences of these cold war "victories." In supplying the Corsican syndicates with money and support, the CIA broke the last barrier to unrestricted Corsican smuggling operations in Marseille. When control over the docks was compounded with the political influence the milieu gained with CIA assistance in 1947, conditions were ideal for Marseille's growth as America's heroin laboratory. The French police later reported that Marseille's first heroin laboratories were opened in 1951, only months after the milieu took over the waterfront.

Gaston Defferre and the Socialist party also emerged victorious after the 1947 and 1950 strikes weakened the local Communist party. From 1953 until the present, Defferre and the Socialists have enjoyed an unbroken political reign over the Marseille municipal government. The Guerinis seem to have maintained a relationship with Marseille's Socialists. Members of the Guerini organization acted as bodyguards and campaign workers for local Socialist candidates until the family's downfall in 1967.

The control of the Guerini brothers over Marseille's heroin industry was so complete that for nearly twenty years they were able to impose an absolute ban on drug peddling inside France at the same time they were exporting vast quantities of heroin to the United States. With their decline in power, due mostly to their unsuccessful vendetta with Marcel Francisci in the mid sixties, their embargo on domestic drug trafficking became unenforceable, and.. France developed a drug problem of her own. (61)