| Articles - Work and work place |

Drug Abuse

AIR CREW ALCOHOL AND DRUG POLICIES:

A SURVEY OF COMMERCIAL AIRLINES

Christopher CH Cook, Kent Institute of Medicine and Health Science, University of Kent at Canterbury, UK

The aviation industry operates in a safety sensitive environment, in which there has been appropriate concern regarding the formation of alcohol and drug policies. A survey was conducted concerning alcohol and drug policies in commercial aviation, with particular reference to those issues affecting flight crews. Most companies did have their own alcohol and drug policies, even though such matters are also the subject of national legislation and international regulation. Alcohol policies mostly concentrated on regulating against alcohol consumption during flight and within a given time period relative to flight. Relatively few airlines employed screening procedures designed to detect alcohol or drug misuse in aircrews. In commercial, passenger carrying, aviation serious alcohol or drug related accidents are rare. It might therefore be argued that such policies are highly effective. However, the extent to which the existence or content of such policies has contributed to this safety record requires further research.

INTRODUCTION

There are certain contexts within which even very modest drinking may increase the risk of alcohol related harm to an unacceptable degree. The most commonly occurring contextual drinking problem is probably that of drinking and driving, and this accounts for a substantial morbidity and mortality in many countries worldwide (Edwards et al., 1994). However, the context of driving a motor vehicle is by no means the most sensitive or hazardous environment as far as drinking is concerned, and there are many workplace environments in which even minimal impairment of performance by alcohol consumption could prove fatal, not only for the drinker, but also for many other innocent parties. Amongst these safety sensitive environments, aviation is one which is especially sensitive to performance deficits, and in which the potential costs are particularly high.

Contextual drinking problems are amenable to prevention through the introduction of appropriate, relevant and focused policies. This has been particularly well demonstrated in respect of drinking and driving (Edwards et al., 1994), yet surprisingly little research has been conducted in other contexts. In the aviation environment, there certainly has not been a failure to form policy, nor has there been evidence that policies are ineffective. However, there does appear to have been a failure to subject such policies to scientific study.

A study of alcohol and drug policies in the aviation environment would therefore appear to be a profitable exercise. The apparent rarity of alcohol induced accidents in this setting (Holdener, 1993) would suggest that lessons may be learnt for the benefit of other alcohol sensitive contexts. The potentially great costs (financial and human) of a major commercial aviation disaster would suggest that it is important to maintain and improve effective policies which are designed to protect both employees and passengers alike.

Aviation alcohol and drug policy is determined at three levels: international, national and by each airline/air force (see Cook, 1997 for a review of policy formation in this field). The International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO) determines common international requirements to which all member states subscribe (International Civil Aviation Organization, 1995). ICAO licensing requirements for aircraft maintenance personnel, air traffic controllers, flight operations officers, and aeronautical station operators, as well as flight crew, specify that a license applicant shall have no established history or clinical diagnosis of alcoholism or drug dependence. Periodic medical assessments, specified in the regulations, provide an opportunity for the detection of alcohol or drug problems arising in existing license holders. Finally, the regulations prohibit pilots and other flight crew from flying whilst their performance is impaired by alcohol or other drugs.

Various national bodies, such as the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) in the United Kingdom and the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) in the United States of America, determine national policy, which is usually enshrined in legislation (Federal Aviation Administration, 1986). Individual airlines and airforces also have their own policies that impose additional restrictions over and above national and international legislation. The present study was designed to collate and describe the experience of commercial airlines in alcohol and drug policy formation, with particular emphasis upon those aspects affecting aircrew.

METHODOLOGY

A brief questionnaire was sent by post to all 196 airlines listed in the 1993/4 Flight directory (Ginsberg, 1993). The questionnaire was initially addressed to the 'Senior Occupational Physician', as it was assumed that most airlines would have links with a physician advising on fitness of aircrew to fly.

Six main questions were asked, each one requiring a YES/NO response as to whether or not the company had a policy concerning:

1. Alcohol consumption by aircrew prior to flight.

2. Illicit drug use by aircrew.

3. Use of prescribed and 'over the counter' medication by aircrew.

4. Screening of aircrew for alcohol/drug misuse.

5. Prevention of alcohol/drug misuse amongst air crew.

6. Management of alcohol misuse in aircrew.

In each case, details of the policy were requested, and the respondent was asked to send a copy of any written policy where possible. An addressed envelope was enclosed in order to facilitate reply.

The first mailing of the questionnaire took place in April 1994. A second mailing was carried out in June 1994, as a follow up to all those companies that had still not replied. Where companies had indicated that they would participate, but had still not returned a questionnaire, a third letter was sent in January 1995. For those companies that did not respond to the third letter, a final contact was made by telephone during the early part of 1995.

Data were entered onto a computer database and analysed using SPSS statistical software.

RESULTS

Response rates

Ninety-two airlines (24 UK and 68 other) participated in the survey, representing an overall response rate of 47% (67% for UK airlines and 43% for other airlines). However, 22 questionnaires were undelivered, the letters being returned by the Post Office with no explanation, and no other address being known. Eight other airlines had ceased trading. The response rate from airlines that were still trading and which received a questionnaire was thus 55% (73% for UK airlines and 5 1% for other airlines). Only four airlines refused to participate. The remainder simply did not return a questionnaire, despite being reminded of the survey. In at least two cases, this was because of a language barrier.

In many cases, the respondant was a chief pilot or other executive and not a physician.

Existence of a policy

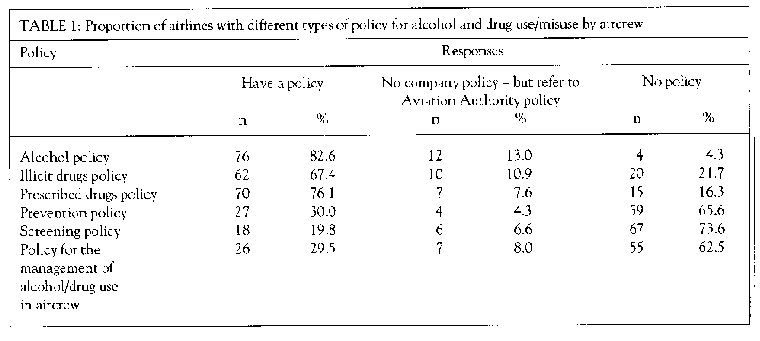

Table I indicates the responses of the participating airlines to each of the major questions asked. Although the questionnaire was intended to refer only to company policy, some companies replied to the effect that they observed ICAO or national aviation authority policy. These replies are indicated separately in Table 1, although they strictly amount to a 'NO' response. Of 12 such replies to the question on alcohol policy, 2 referred to ICAO policy, 2 to the CAA, 4 to the FAA and 1 to 'government legislation'. The remaining three responses in this group were from Arab countries where abstinence from alcohol is enforced by laws applicable to the whole population. It is apparent from Table I that the vast majority of airlines have their own policies covering the use of alcohol, illicit drugs and prescribed drugs by aircrews. Only a minority of airlines have policies covering prevention of alcohol and drug problems, screening measures, and management of detected cases. Out of the four airlines that answered 'No' to the question on alcohol policy, two were from Arab States in which abstinence is enforced by national law. One other airline indicated that its alcohol policy was 'under revision'.

Alcohol policies

Out of the 76 companies that replied 'YES' to the question on alcohol policy, 56 (75%) sent a copy of their policy. The remainder provided variable amounts of information, of variable quality, describing the content of their policy.

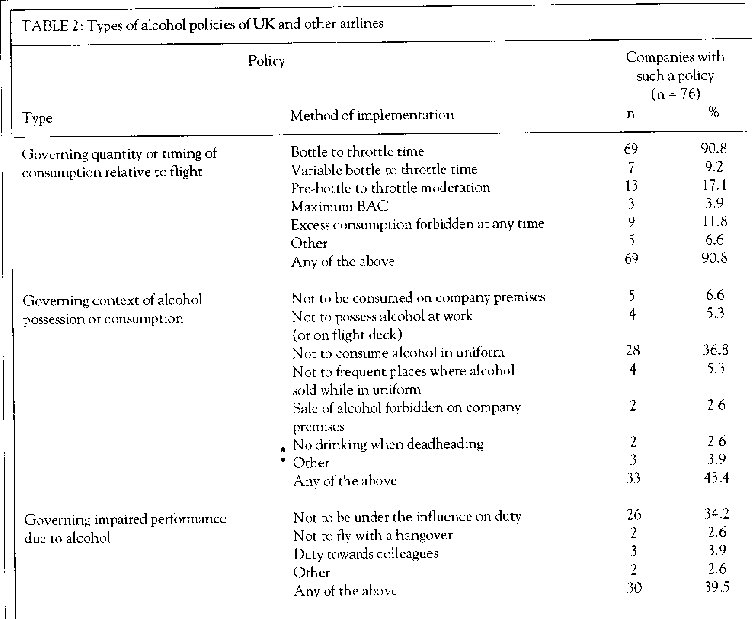

Careful study of these policies revealed that they comprised a combination of different elements which could be categorised under three main headings. The characteristics of these three groups were as follows:

1. Policies governing quantity or timing of alcohol consumption relative to flight

The general intention of these clauses, although often not explicitly stated, appeared to be that the blood alcohol concentration (BAC) of aircrews on duty should either be 'zero', or else kept to a minimum. Usually this was achieved either by limiting he quantity of consumption, or else by restricting he timing of consumption relative to flying duties. However, a variety of other approaches were also raised. Rarely, a maximum BAC was specified.

The most commonly adopted approach in this category, was to specify a 'bottle to throttle' time. 17his is a defined period of time before reporting for Jury, during which aircrew may not consume alcohol. Variations on this approach include variable bottle to throttle times, dependent upon previous alcohol consumption, and specification of pre-bottle to throttle periods of moderate drinking.

2. Policies governing the context of alcohol possession or consumption

The intention of these clauses appeared to be the prohibition of alcohol consumption in places or circumstances that would either be likely to result in intoxication on duty, or else would potentially impair the reputation of the airline (by making i.t appear that intoxication on duty was permissible).

Examples of such policies include stipulations that alcohol is not to be consumed on company premises or when in uniform, or that places where alcohol is sold should not he frequented whilst in uniform.

3. Policies that govern impaired performance attributable to alcohol consumption

The intention of these clauses appeared to be that aircrew should not fly if their performance was impaired by alcohol. The implicit assumption in these clauses appears to be that aircrew should themselves know and identify whether or not their performance is actually impaired as a result of their drinking.

In most cases these policies simply included an instruction not to fly whilst under the influence of alcohol. In three cases only, an obligation was imposed that aircrew should not fly with colleagues who were under the influence of alcohol.

A limited number of methods of achieving these three policy options appeared to have been devised and utilised by the airlines responding to the survey. In some cases, identical wording suggested that policies had been copied from a common source. In most cases, the principles rather than the text appeared to have been transcribed.

The numbers of airlines utilising the various clauses that were identified under each of these three headings are shown in Table 2. It may be seen that policies governing the quantity or timing of alcohol consumption were the most frequently employed, mainly by virtue of the great popularity of the 'bottle to throttle' rule. Approximately 40% of airlines employed each of the other approaches (governing context of alcohol consumption and impaired performance).

The period of time prior to duty for which abstinence is enforced (the 'bottle to throttle time'), in the various airline policies that incorporated such measures, ranged from 8 hours to 72 hours. Amongst 69 airlines, only five different time periods (8,10,12, 24 and 72 hours) are specified. The single most popular 'bottle to throttle' time (n = 39 airlines) is also the shortest, at only 8 hours. A 10 hour interval was specified by seven airlines, and a 12-hour interval by 16 airlines. Only six airlines specified a 24-hour period of abstinence, and only one airline specified a 72 hour period.

Some airlines have made qualifications to their bottle to throttle rules. Seven airlines specified that the bottle to throttle period of abstinence should be longer (in two cases 14 hours, in five cases not specified) if prior drinking was 'not moderate'. These airlines all had bottle to throttle rules that otherwise specified only a short period of abstinence prior to duty (8 hours). Thirteen airlines specified a period of moderation prior to the bottle to throttle period. These airlines had very variable bottle to throttle periods (824 hours), and the additional specified period of abstinence was also very variable (4-24 hours). However, in eight out of these 13 airlines, the normally specified interval was eight hours, and the additionally specified period of prior moderation was 16 hours.

It might be expected that cultural factors would strongly influence airline alcohol policy. In order to investigate this possibility further, 15 airlines from Arab States in the Middle East were identified from the original mailing list. The questionnaire sent to one of these airlines was undeliverable at the address given, and one other airline failed to return a questionnaire. Five airlines, from countries in which total abstinence from alcohol is enforced by law for the whole population, either indicated that they did not have a policy, or else referred to their national legislation. It was indicated that in at least one of these countries extremely severe penalties for drinking were enforced by national legislation. Of the remaining airlines, one referred to ICAO policy, and seven gave details of their own policies, which were not obviousy different from those of other international airlines.

Drug policies

In most cases, drug policies were much more briefly described and defined than were alcohol policies.

Because of this, and because of lack of information provided by respondents, a comprehensive classification of these policies has not be attempted here. However, in at least 12 cases where it was indicated that there was an illicit drug policy, this appeared to refer to general policy provisions concerning the use of any drugs. In seven of these cases, proscription of illicit drug use by aircrews appeared to be subsumed under a policy prohibiting use of any drug that was not either prescribed or else taken under appropriate medical instruction. In the other five cases, illicit drug use was apparently subsumed under instructions prohibiting use of any drugs that might impair performance on duty.

Prescribed drug policies

Prescribed drug policies entailed varying detail regarding specific drugs or groups of drugs, including' over the counter' medications as well as prescription only drugs. In many cases they recommended or required that advice be sought from a company medical practitioner or from an approved aviation medical examiner,

Screening policies

Eighteen airlines indicated that they had an alcohol and/or drugs screening programme for aircrew. Unfortunately, variable amounts of detail were provided, and in two cases no information was provided at all. Two airlines referred only to conducting medical examinations; in one case on a 'frequent' basis, and in the other case on a 'random' basis prior to flying duties. Six airlines referred to specific tests for illicit drugs, mostly modelled on FAA guidelines. Eleven airlines referred to specific tests for alcohol, including seven that specified the use of breathalysers. Of the 11 airlines conducting screening for alcohol intoxication, the context of testing was: random (5), pre-duty (3), post accident (4), pre-employment (3), or on 'reasonable cause'(4).

Prevention policies

In many cases it was not clear from the responses given that respondents had understood the distinction between the broader issue of prevention of drug and alcohol misuse, and the specific alcohol/drug policy issues addressed in other parts of the questionnaire. Few respondents gave any details in their answer to this question, and it appeared likely that most of those giving a positive reply considered any drug/alcohol policy to be a 'prevention' policy. However, inspection of the policy documents provided by some respondents revealed references to 'increasing awareness' of drug and alcohol problems, or a commitment to creating a 'drug/alcohol free workplace'. One company had prepared its own guide to alcohol/drugs for flight crew.

Management policies

Amongst respondents indicating that their company had a policy, very few provided details concerning the nature of the policy that was implemented. Some companies only gave indication of a disciplinary response, sometimes including dismissal. Others indicated that counselling and rehabilitation would he necessary, and in some cases this was to he at company expense. It was indicated in two responses that only one opportunity would be offered for rehabilitation and that dismissal would follow any relapse. Where rehabilitation was an available option, some sort of arrangement was provided for follow-up to ensure both a good outcome for the employee, and also safety in the aviation environment. Suspension from flying duties was invariably mandated during the process of rehabilitation.

DISCUSSION

The response rate observed in this survey is reasonable for a self-report questionnaire mailing, and is arguably very good in respect of UK based airlines. However, it is clear that many airlines did not participate, and that they may be dissimilar from those thatdid. For example, the response rate was much higher amongst UK airlines, perhaps representing a tendency for respondents to be more willing or able to reply to a survey originating from their home country. Unfortunately, data concerning the fleet size, annual numbers of passengers and annual tonnage of freight transported were not readily available for the majority of airlines. It is therefore not possible to make calculations concerning the extent to which various policies apply to the total numbers of international commercial aircraft, or passengers/freight transported.

Whilst the above comments may limit the extent to which the policies described are considered representative of airlines in general, there is no obvious reason to believe that the group of non responders harbours policies which are novel, more effective, or more comprehensive than those of other airlines. Indeed, the combined sample of policies described in this survey appeared to have considered almost every conceivable aspect of alcohol or drug use and misuse by aircrew which might reasonably be the object of policy making. There is, of course, a danger that the non-responding airlines might have poorer policies, and that they did not respond because of a concern not to be seen to have inadequate policies. The overall picture may therefore not be as good as the one painted here.

The data indicate that almost all airlines have an alcohol policy for aircrew. This presumably reflects a perception that such policies are necessary and important in view of the high prevalence of alcohol use and the potential seriousness of the risk that alcohol poses in this context. However, surprisingly few airlines appeared to have taken more general measures to prevent alcohol problems amongst flight crew. Unfortunately, the questionnaire employed in the present survey appears not to have clarified this issue sufficiently, but very few of the policy documents supplied by participating airlines indicated that this issue had been addressed. Possibly it was felt that other policies already provided a sufficient preventive intervention. Alternatively, it may be considered that companies should only focus on those aspects of employee behaviour which directly impinge upon their work, and that more general or indirect measures constitute an intrusion on privacy. Again, it l-nay be considered that more general health education of this sort is the province of measures aimed at the whole population, and that contextual groups such as aircrew should not be singled out for special treatment. Whatever the possible explanations, policies have been heavily weighted towards the important and laudable, but specific, context of avoiding intoxication on duty. The more general goal of reducing aircrew alcohol consumption and alcohol related problems appears to have been ignored by most airlines. However, given the already very low prevalence of problems in this sphere, it is debatable as to whether or not there is any need to redress this imbalance.

Given the limited options available, almost every conceivable or possible policy option appears to have been explored in an effort to prevent a pilot from flying an aircraft when intoxicated. However, the efforts that have been made also highlight the near impossibility of achieving this objective by means of policy making. This is illustrated by considering the case of a pilot who drinks heavily on a single occassion. An intake of, for example, 10 pints of beer would take approximately 20 hours for complete clearance from the blood stream. If we assume that any BAC above 0 mg/dl is undesirable, and there is evidence that a BAC as low as 11 mg/dl impairs aircrew performance (Davenport and Harris, 1992), then only seven airlines would have prevented such an individual from flying while intoxicated by means of their bottle to throttle policies alone. One more airline may have achieved the same effect by imposing a 24-hour period of moderation prior to an eight-hour bottle to throttle period. However, even these airlines have not addressed the potential risks of continuing impairment beyond the point at which BAC has returned to 'zero' (Post Alcohol Impairment or 'PAI', Gibbons, 1988). PAI could impose a continuing risk to flight safety beyond all but the longest bottle to throttle times. In this survey, only the airline with a 7 2-hour bottle to throttle time could be confident in this regard.

Injunctions not to fly 'under the influence' of alcohol are excellent in theory, but may be unreasonable in practice. It would be extremely difficult for aircrew to judge if their performance was impaired unless they were either given opportunity to test this in practice, or they were given a high level of education as to the effects of particular quantities/patterns of alcohol consumption. No airline gave indication of providing the opportunity to conduct such practical tests, and very few airlines appeared to give any appreciable amount of education or information to their crews on such matters.

Whilst it is relatively easy to find fault with the policies that airlines have introduced, it is clear that the great majority have taken positive, and apparently effective, steps to prevent alcohol and drug related problems amongst their aircrew. Additionally, such matters are addressed by national and international regulatory bodies. To the extent that commercial passenger carrying aviation accidents attributable to alcohol or drug use by aircrew are very rare (and unheard of in so-called 'Part 121'carriers), this would appear to be a success story with lessons to be learnt by other areas of industry. However, more research is required in order to establish which of the policies identified in this survey are most effective, and what the most effective combination of such policies might be.

It is interesting to speculate as to how effective the policies described in this survey might be, if applied to other forms of aviation. For example, if private pilots were compelled to observe similar restrictions, would this reduce alcohol related general aviation accidents? Aside from the enforcement issues that would arise, it is arguable that the employment context, including selection and screening pre-employment, is actually itself a more effective influence. The risk of losing a job, not to mention the responsibility of the safety of large numbers of passengers, must be a very real incentive to be responsible in respect of alcohol and drug use.

Within the group of airlines studied, there are also obvious cultural differences. In Arab countries alcohol use and misuse is less of a problem, and in many cases national legislation already prohibits alcohol use. Accordingly, the need for airline alcohol policies may be perceived as less important.

Screening policies were surprisingly infrequent in the sample of airlines studied. Alongside statistics of alcohol related aviation accidents, and numbers of aircrew with alcohol/drug problems identified through other channels, the results of screening provide the only means of monitoring the effectiveness of other policies. If the results of research on drinking and driving are applicable to the aviation context, they would support the contention that random testing may also be an effective intervention to reduce the prevalence of flying while intoxicated (Edwards et al., 1994). However, a pre-flight breathalyser still does not accommodate the problems associated with PAI.

Most airlines gave few details concerning their policy for management of an identified alcohol or drug problem in aircrew. The few companies that did give such information asked that it he kept confidential; detailed reporting here would be likely to prejudice that confidentiality. However, other publications have already described examples of such programmes (Flynn et al., 1993; Holdener, 1993).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My thanks are due to Ms J. Chester, at the Royal Air Force Medical Library, and DRIC translation services, for their help in obtaining translations of song~ of the non-English policy documents. 1 am also very grateful to all the airlines that participated in this survey.

Professor Christopher CH Cook, Professor of the Psychiatry of Alcohol Misuse, Kent Institute of Medicine and Health Science, University of Kent atCanterbury, Canterbury, Kent CT2 7NR.

REFERENCES

Cook CCH (1997). Alcohol policy and aviation safety. Addiction 92: 793-804.

Davenport M, Harris D (1992). The effect of low blood alcohol levels on pilot performance in a series of simulated approach and landing trials. The International journal of Aviation Psychology 2: 2 7 1-80.

Edwards G, Anderson P, Babor TF, Casswell S, Ferrence R, Giesbrecht N, Godfrey C, Holder HD, Lemmens P, M5kehi K, Midanik LT, Norstr6m T, Osterberg E, Romelsib A,RoomR, Simpuraj, SkogO-J (1994a). Alcohol Policy and the Public Good. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 153-9.

Federal Aviation Administration 0 986). Federal Aviation Regulations. Washington DC: Department of Transportation.

Flynn CF, Sturges MS, Swarsen RJ, Kohn GM (1993). Alcoholism and treatment in airline aviators: One company's results. Aviation Space and Environmental Medicine 64: 314-8.

Gibbons HL (1988). Alcohol, aviation, and safety revisited: A historical review and a suggestion. Aviation Space and Environmental Medicine 59: 657-60.

GinsbergM (Ed) (1993). Flight International Directory: Partl UK and Ireland DirectorN 1993/4. Potters Bar: Flight International Directories.

Holdener F (1993). Alcohol and civil aviation. Addiction 88: 953-8.

International Civil Aviation Organization (1995). Manual on PreventionofProblematic UseofSubstancesin the Aviation Workplace. Montreal: International Civil Aviation Organisation.