| Articles - Supply reduction |

Drug Abuse

NOTES FROM THE DRUG WARS By Ernest Drucker The real gulf and the phoney war

The war in the Persian Gulf overwhelms us with its high tech lethality, diminishing our sense of humanity just that much more. It puts us in our place with a startling display of military power and reminds us about Will and Force, and just how hard the hard boys can be. In this context, the Drug Wars are easily forgotten - consigned to a quiet corner of chronic social ills. No longer is there the need to gnash our teeth at junkies - now that we've got Saddam Hussein to hate.

Besides, it is declared, we've "turned the corner" in the Drug War and that "light is visible at the end of the tunnel". The results of the latest federally financed survey from the University of Michigan's Institute for Social Research showed a drop in cocaine use among "main stream" American youth - 15,000 high school seniors who are interviewed each year. For the first time in 16 years, fewer than half those surveyed report ever using an "illicit drug" - down from a high of 66% eight years ago. U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services Louis W. Sullivan, said "This is a significant milestone underlying considerable progress in our efforts to replace a drug culture with a culture of character, convincing students that drugs are not a rite of passage, but a road to disaster".

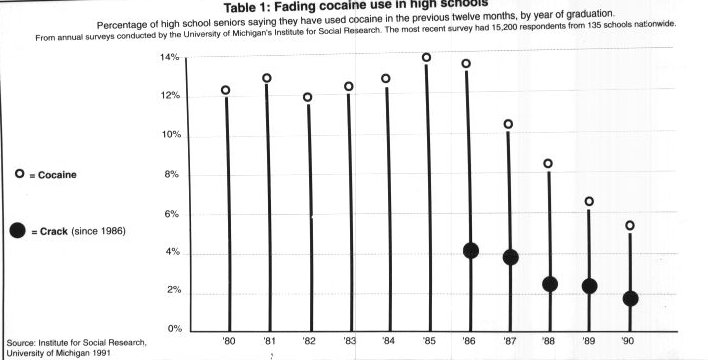

Cocaine is singled out for special attention (See Table 1 ) and cited as the most significant victory of the War on Drugs. "Crack and cocaine are finished when it comes to young people in the middle classes" said Mathea Falco, former Assistant Secretary of State for international narcotic matters in the Carter Administration. The survey showed that 5.3% of seniors (age 17-18) used the drug at least once in the last years down from a high of 13% in 1986. And use within the last month fel to 1.9% from a high of ¢.7% in 1986. Crack use during the previous year declined even further in this group - 1.9% in 1989-1990, down from 4% in 1986. Regular use of crack would, of course, be only a fraction of both rates.

But all is not rosy at Riverdale High. The evidence from the same survey suggests a shift to alcohol and at rates which the Michigan research called "staggering". Nearly a third said they had consumed five or more drinks in a row within the last two weeks. And tobacco use, for the seventh straight year, remains unabated - 19% smoke daily,11 % smoking half a pack or more each day. Yet, somehow, these results are interpreted to mean that "drug use" is going down due to the effort of the Drug War.

If "casual use" of cocaine by the middle class has dramatically declined (by 45%-50% according to a household survey of adults by NIDA), the regular or heavy use of cocaine and heroin shows no such trend. A report from Senator Joe Biden (based, l believe, on some work of Harvard’s Mark Kleiman) estimates the U.S. to still have 2.4 million "hard core" cocaine users. While this number is fairly meaningless (what’s the definition of level of use and how is it validated?), there is some independent evidence of the establishment of a cohort - a fixed group of users established with fewer new entrants, with some dropping out or going to prison, and others dying "in combat". NIDA estimates a lower level of regular users (once a week or more, declining ftom 862,000 in 1986 to 662,000 in 1990. Yet, in the same period, daily use is judged to have increased by about 15% - from 292,00( to 336,000.

An on-going survey by the US National Institute of Justice monitors levels of use among people arrested fo felony offenses (excluding drug possession.charges per se) in 22 US cities.

This survey indicates a peaking of cocaine use among the heavy users in the American ghetto - the population most likely to get caught in the net of the criminal justice system. An astonishing 74% of all New York City felony arrests in 1988 were positive for cocaine - as were 25% of all auto fatalities in the City. Now the jail figures have dropped to 66%, as have emergency room incidents associated with cocaine toxicity.

The urban anthropologist, Ansley Hamid, studying the political economy of the crack trade in Harlem and Brooklyn, also reports a decline in crack cases - especially in the appearance of new users. Noting an increase in price as well, Hamid reasons that dealers are trying to extract the same level of earnings from a shrinking market - a paradox of supply and demand if ever one was seen but consistent with some other peculiarities of the drug economy. (Hamid’s article The decline of crack use in New York City: Drug policy or natural controls? will appear in the next issue of IJDP).

And, while the war in the Persian Gulf occupies most of the limited attention span of the press and public, the hemispheric drug trade is doing just fine. Since January 16 and the start of hostilities, the following items appeared in New York newspapers providing a sidebar to the main event - even as US battle ships fire cruise missiles so accurate they could go down the chimney of a building 600 miles away in Iraq.

Colombian drug lords have apparently cut a deal with the Gaviria government, avoiding extradition to the US and risking only light sentences prior to their re-entry into the mainstream of society. Local journalists still have some fight left in them but, with the murder of Diana Turbay, magazine editor and daughter of a former President of the Republic, journalists who speak out against the Cali and Medellin cartels are getting scarce. As many as 100 Colombian journalists are living out of the country in "self-exile" and 30 more have been slain in the last two years. The morning after a remote controlled bomb exploded in Medellin killing seven policemen, El Colombiano, the City’s largest circulation paper, carried a front page lead headline: "Drug Trafficking Study Proposes Decriminalization and Elimination of Extradition".

But peace talks in Colombia continue and this year may see the surrender of 300 traffickers in exchange for leniency in sentencing and protection from extradition to the US - the thing they fear the most. U.S. drug officials are incensed by these "concessions" calling the shelter from extradition "a devastating blow" and threatening to withhold nearly $100 million in miiitary assistance. Still, the desire for a negotiated settlement grows in popularity. "It’s time to stop pursuing a war that oniy interests the United States", said Humberto Samorano, a 23 year old university student interviewed by James Brooke of the New York Times in Medellin last December, "It’s their problem if they can’t educate their people to stop taking drugs".

Meanwhile in Peru, the Sendero Luminoso continues to make political capital of the drug wars and the presence of US military "advisors" stationed in the upper Hualaga Valley, where they have built a firebase reminiscent of Vietnam. The guerilla war in this desperately poor country has left cocaine as the dominant single economic activity, and who controls it would appear to control Peru. So powerful have the guerrillas grown that Lima, the capital and home to over one-third of Peru’s 22 million people, now spends 25% of its time without electricity - power pylons being a favourite target and a reminder to the urban population of just who dominates the countryside.

And Equador, sandwiched between Peru, the world’s largest coca leaf grower, and Colombia, the world’s largest cocaine refiner, is now also a combatant in the hemispheric drug wars. Its ports became relatively safe havens for cocaine shipments north and the laundering of drug money in Equador is already a very big business - estimated at $700 billion last year in an economy whose entire GNP is only $12 billion. Farmiand bordering Peru and Colombia is being bought up by foreign "investors" at triple its current value. The town of Santo Domingo de los Colorados, a regional centre in the north, has attracted so much cocaine cartel investment, that locals refer to it now as "Santo Domingo de los Colombianos" .

Equador’s geography virtually assures its growing role in the regional drug economy, following a recent history of significant coca crop eradication in the mid 1980s. This shift is visible in growing seizures of drugs (500 pounds of pure cocaine were recently seized in Guayaquil and increased imports of precursor chemicals such as acetone and caustic soda. Now for the first time in this tranquil society, sharp armed conflicts with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, who seek to control the area’s coca leaf plantations and refineries, are becoming evident.

But the US, in a belligerent mood these days, clings to the model of war | at home as well as abroad. And I combatants for both wars are increasingly drawn from America’s minority population - especially Blacks. The U.S. population as a whole is 12% Black, but the US combat forces in the Persian Gulf are 30% Black. And there are more young Black men in American prisons than in American colleges. 25 of all Black men in America, between the ages of 20 and 30, are in prison or on probation or parole following prison. More than half of these inmates are there for drug-related offenses.

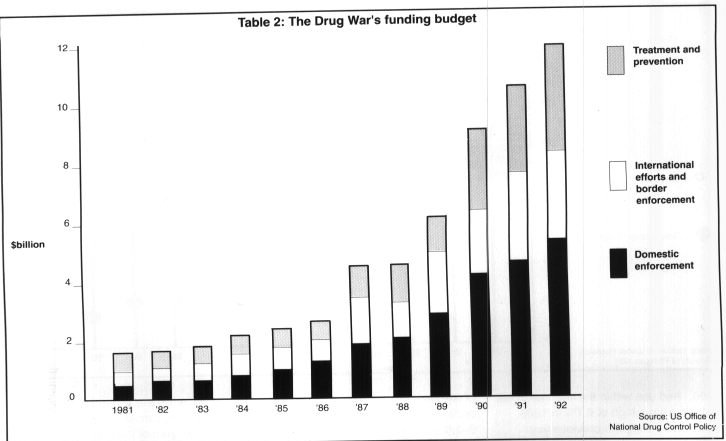

Examining the big increases in the US Drug War budget (from 1986-1990), makes clear that the lion’s share of increases are for prison and domestic enforcement - an approach whose principal result has been to intimidate the middle class to reduce their recreational drug use and shift to alcohol. But the Drug War budget has had little effect on heavy users and provides little treatment for the addicted

So, for the abandoned poor of the inner cities, little has changed. And, despite declarations of victory in this phoney war, the gulf in American society is growing wider than ever.

Ernest Drucker Director, Division of Community Health and Professor of Epidemiology and Social Medicine at Montefiore Medical Centre/Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx, NYC, USA