| Articles - Overdose |

Drug Abuse

Which drugs cause overdose among opiate misusers? Study of personal and witnessed overdoses

JOHN STRANG, PAUL GRIFFITHS, BEVERLY POWIS, JANE FOUNTAIN, SARA WILLIAMSON & MICHAEL GOSSOP

National Addiction Centre, Institute of Psychiatry and the Maudsley Hospital, Denmark Hill, London, United Kingdom

Abstract

Concern has been expressed at the widespread prescribing of methadone in view of its inherent toxicity. Commentators have opined that methadone is more toxic than heroin and causes more overdose deaths. However, data deficiencies and flawed analyses leave continuing uncertainty about this crucial policy issue. The relative contributions of heroin, other opiates (e.g. methadone) and non-opiate drugs to overdose and overdose deaths among drug misusers were examined in a community-recruited sample of 312 injecting drug misusers in London. Data were collected on last personal overdose (n = 117), last witnessed overdose (n = 167) and last witnessed fatal overdose (n = 55), and on the different drugs that had been involved with these overdoses. Heroin was involved in 83% of last personal overdoses, 90% of last witnessed overdoses and 80% of last witnessed fatal overdoses, while other opiates were involved in only 18%, 8% and 26%, respectively. Methadone accounted for about half of these "other opiate" overdoses. Overdoses involving a combination of heroin and a non-opiate were common-29%, 21% and 39%, respectively. Heroin was the drug most frequently involved in overdose across all three areas of study. However, combinations of heroin and a non-opiate were surprisingly frequent, especially in witnessed fatal overdoses (as reported recently by other investigators using different methodologies). Considering the wide extent of methadone prescribing to this group, methadone was remarkably infrequently reported as responsible (solely or in combination) for either personal overdoses, witnessed overdoses or witnessed fatal overdoses. [Strang J, Griffiths P, Powis B, Fountain J, Williamson S, Gossop M. Which drugs cause overdose among opiate misusers? Study of personal and witnessed overdoses. Drug Alcohol Rev 1999;18:253-2613

Key words: overdose; opiate; heroin; methadone; death.

Introduction

Following attention being drawn to the potential toxicity from injudicious prescribing of methadone done [1,2], it has been suggested that methadone produces greater numbers of fatalities and appears to be greatly more toxic than heroin [3–5] and the issue has drawn contributions from forensic colleagues [68]. Extrapolations from Home Office reports have stimulated heated public debate and have prompted criticisms [9-11] of their computations, their loose use of undefined terms such as "methadone deaths" and their incorrect citation of the works of others— and the debate continues [4,5,9-13].

On the basis of these disputed calculations, the recent expansion of methadone substitution programmes has been called into question [14,15]. Increased prescribing of methadone has indeed been a distinctive feature of national responses to the continuing global heroin problem, both in the United Kingdom and in many other countries. For example, total UK national prescribing of methadone increased from 1.7 kg to 9.4 kg over the 5-year period up to 1994 [16]; methadone constituted 96% of all opiate prescriptions to addicts and was being prescribed to four times as many addicts (estimated at 30 000) compared with 7 years earlier [17].

It is vital that the relative contributions of heroin and methadone to overdose deaths among opiate misusers are established. In this paper, we provide new empirical data from a community sample of opiate misusers on the drugs involved and the circumstances pertaining to personal overdose experiences and the witnessed non-fatal and fatal overdoses of others.

Method

Structured interviews were conducted with a community sample of 312 injecting drug misusers in London on the extent to which their own personal overdoses and the overdoses of others which they have witnessed involved either heroin, methadone, other opiates or non-opiate drugs. The data were collected in the context of interviews which explored attitudes to, and behaviour regarding, injecting, and the extent to which they had experienced a wide range of adverse consequences of their drug use, including exploration of the extent to which they had experienced, and witnessed, overdose. (We report elsewhere [18] on the wider context of these overdoses.) These data were collected by structured interviews using a questionnaire with a stem-and-branch design, and administered by one of a team of 24 interviewers who had been selected on the basis of their existing access to drug-taking populations in South London and who had satisfactorily completed an initial training session and supervised sample interview. Field interviews were also tape-recorded to ensure that they had been conducted correctly, and a full de-briefing occurred after each interview. In addition to our earlier consideration of this approach to sample selection [19], practical and methodological aspects of this approach have also been considered elsewhere [20] with the conclusion that the approach provided good population coverage and access to hidden populations.

Inclusion criteria were that the subject had previously (including currently) injected and was currently using injectable drugs (in this instance, "currently" defined as at least once within the last month). Injecting drug misusers (n = 312) were contacted and interviewed by privileged access interviewers (PAI) during 1995/96 (for further details on PAI method, see Griffiths et al. [19]). As we have reported elsewhere in an exploration of the potential benefit that might result from take-home naloxone [21], subjects were asked to describe how they would tell whether someone had overdosed: a wide range of indicative signs were described, including that the person was unconscious (44%); had a distinctively abnormal facial appearance (e.g. blue) (27%); had stopped breathing (11%) or was visibly dead or almost dead (11%). The interviews were followed by collection of a saliva sample for linked anonymous testing of markers for infection with HIV, hepatitis B and C (on which we will report later).

The structured interview took approximately 45 minutes to administer, during which enquiry covered a range of areas including present and past injecting and wider drug-taking behaviour and history of health complications as well as enquiry into the subject's overdose experience. Enquiry about overdoses covered two distinct areas—first, personal experience of overdose and secondly, the witnessing of overdoses by others, and these results are reported separately below. Some of the witnessed overdoses were fatal, and separate additional analyses are presented for these witnessed fatal overdoses. Data were specifically collected on the drugs which had been taken in nonfatal overdoses experienced by our interviewees, and on fatal as well as non-fatal overdoses of other drug users which they had witnessed.

The drugs involved in these overdoses have been examined as being either (a) heroin, (b) other opiates (methadone, dipipanone, dextromoramide, etc.) and/ or (c) non-opiate drugs (barbiturates, benzodiazepines, etc.). In view of the extensive reliance on methadone in substitution treatment programmes in the United Kingdom [22] and the particular concerns about methadone voiced by Marks [3] and Newcombe [4,5], data are presented separately on the extent to which the "other opiate" was methadone.

Results

Demographic characteristics of the study sample

The study sample (n = 312) comprised 196 men (63%) and 116 women (37%), all of whom were current injectors (i.e. had injected at least once in the month prior to interview). Mean age was 30.6 years (range 14-54), with the majority of the sample (285, 91%) being white, most of the remainder describing themselves ethnically as of Afro-Caribbean origin (21, 7%). The majority (290, 93%) had been involved in heroin use in the year prior to interview, although many had also used other drugs including methadone (238, 76%) and cocaine (186, 60%). Several also drank alcohol heavily, including 22 men and 16 women who had been drinking alcohol above recommended sensible limits (21 units of alcohol per week for men and 14 units per week for women) in the week prior to interview. Most subjects had an extensive history of intravenous drug use, with a mean duration of injecting for the sample of 10 years (range 1-40 years), amongst whom 87% (272) had injected heroin in the month prior to interview. Mean number of days

Heroin (n =97)

of injecting in the month prior to interview was 19 (range 1-31). Of these 312 injectors, 71% (220) had at some point been in treatment for their drug problem, including 150 (48% of the total sample) who were currently receiving treatment. A total of 238 (76% of the sample) had used methadone in the year prior to interview, of whom 184 (59% of the total sample; 77% of those who had used methadone) had received at least part of this supply of methadone on a prescription to themselves.

Overdose history

Personal overdose history

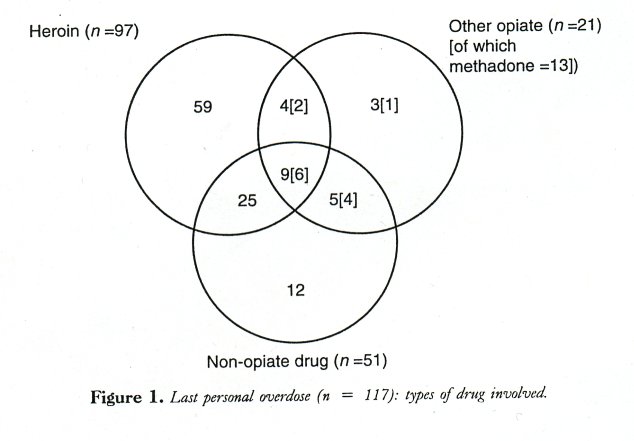

One hundred and seventeen (38%) of the 312 injecting drug misusers had suffered at least one overdose. Seventy-one (61%) identified a single drug of overdose, while 27 (23%) had taken two drugs and 19 (16%) had taken three or more drugs. (Some of these different drugs may have been from the same group (e.g. two different opiates), and hence a lesser extent of overlap is shown in Fig. 1 where, for example, an overdose with 2 non-opiate drugs is displayed as non-opiate only.) These personal overdoses had occurred a mean of S years ago, with 30 of these 117 subjects (26%) having had this overdose within the year prior to interview.

Last personal overdose had involved heroin for 97 (83%), other opiates for 21 (18%) and non-opiate drugs for 51 (44%). Methadone was one of the drugs of overdose for 13 (subsumed within the 21 already reported)—in combination with heroin for eight, and in combination with a non-opiate for 10, and was the only drug of overdose for only one. For 94 of these 117 subjects who had themselves overdosed, they were taking drugs by injection on the occasion of this overdose (for the remainder, the route was oral). Alcohol had been consumed on the day of overdose for 61 of these 117 (52%), with the mean number of units of alcohol drunk by these subjects on the day of their overdose being 17 units.

Witnessing of overdoses by others

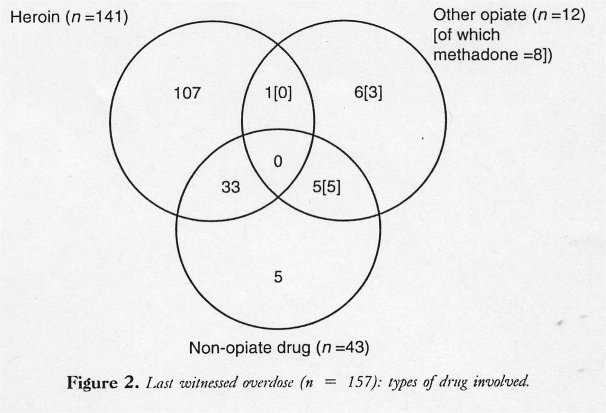

One hundred and sixty-seven (54%) of the 312 injecting drug misusers had witnessed an overdose by another drug user, with 157 of them being able to identify the drugs involved at this last witnessed overdose. One hundred and fifteen (73%) identified a single drug of overdose, 40 (25%) identified the two drugs had been taken, while only two (1%) identified three or more drugs.

Last witnessed overdose had involved heroin. for 141 (90%), other opiates for 12 (8%), and non-opiate drugs for 43 (27%). Methadone was one of the drugs of overdose for eight (already included in the 12 reported as "other opiates")—five of which were in combination with a non-opiate, and as the only drug of overdose for three (Fig. 2).

Witnessed fatal overdoses

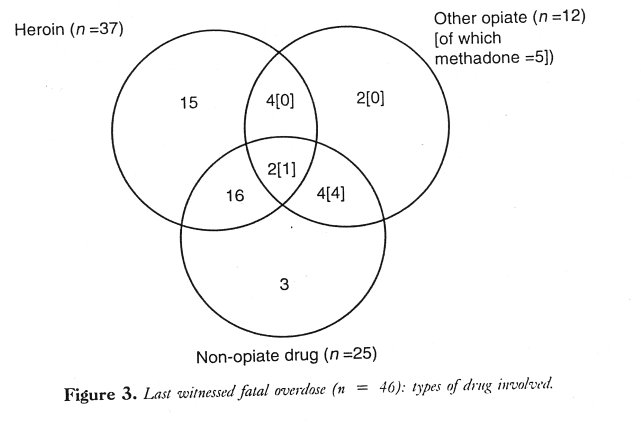

Fatal overdoses had been witnessed by 55 of the 312 injecting drug misusers-18% of the total sample, and 33% of those who had witnessed an overdose. Forty-six interviewees were able to identify the drugs involved, with 19 (41%) identifying a single drug, 20 (43%) reporting that two drugs had been involved, and with seven (15%) identifying three or more drugs that had led to the fatal overdose.

Witnessed fatal overdoses had involved heroin for 37 (80%), other opiates for 12 (26%) and non-opiate drugs for 25 (54%). Methadone was one of the drugs of overdose for five (part of the 12 reported as "other opiates")—in combination with non-opiates in all five instances, and with heroin also being taken with one of the fatal overdoses (Fig. 3).

Drugs involved in `other opiate" overdoses

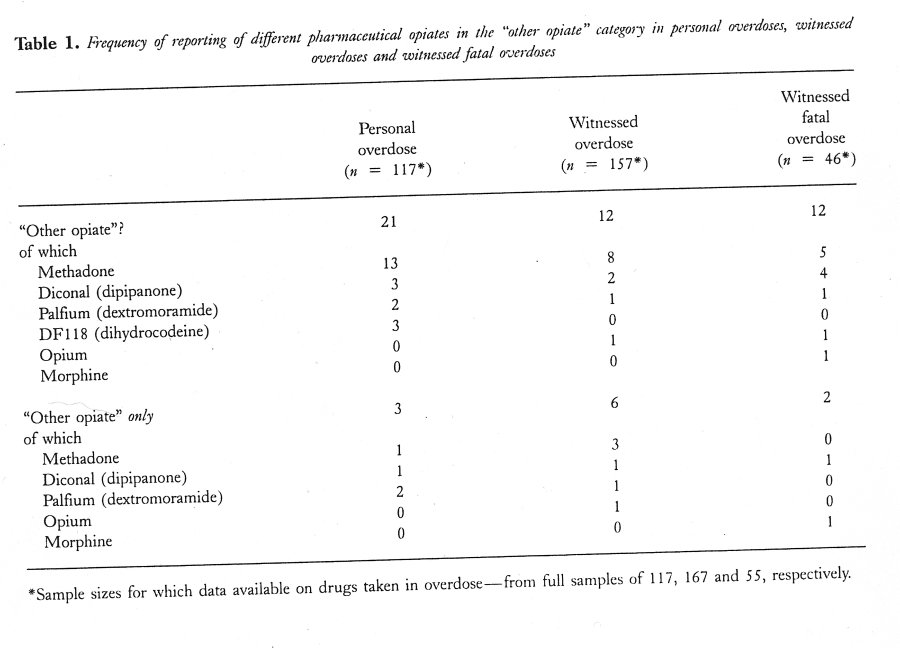

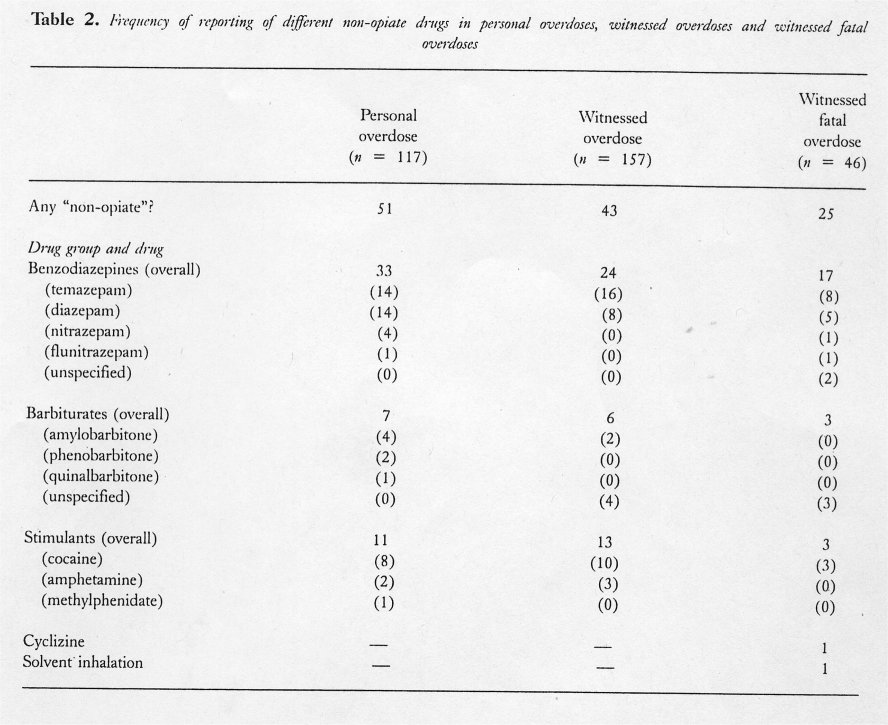

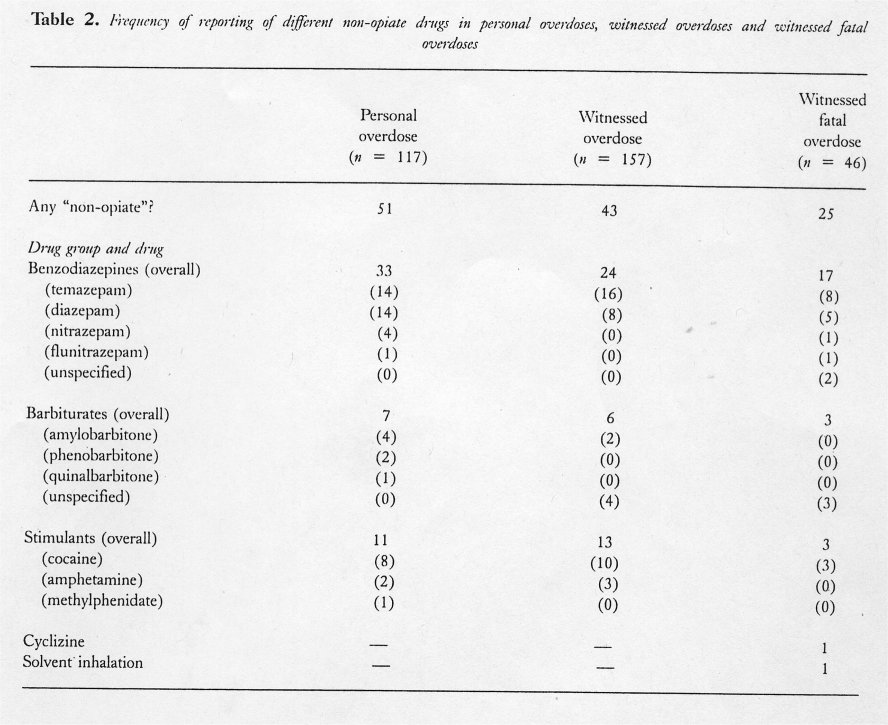

As reported in the preceding sections, "other opiates" (i.e. not heroin) had been taken in 18% of personal overdoses, 8% of witnessed overdoses and 26% of fatal overdoses in our study, although the proportions of these overdoses which involved only these "other opiates" were much lower at 3%, 4% and 4%, respectively. The pharmaceutical opiates most frequently reported in the "other opiate" category are shown in Table 1.

Methadone had been taken in about half of the overdoses involving "other opiates"—personal overdoses (62%), witnessed overdoses (67%) and fatal overdoses (42%). Diconal (dipipanone) had been the "other opiate" taken in three of the 21 personal overdoses (14%) and in two of the 12 witnessed overdoses (17%) involving other opiates. Among the 12 "other opiate" fatal overdoses, five (42%) had involved methadone and four (33%) had involved Diconal (dipipanone).

The analysis has then been restricted to overdoses in which only an "other opiate" had been taken (see lower half of Table 1). Of the 11 overdoses involving only "other opiate", four involved methadone (including neither of the two fatal overdoses), three involved Diconal (dipipanone) (including one fatality) and two Palfium (dextromoramide).

Drugs involved in "non-opiate" overdoses

As reported above, "non-opiates" had been taken on 44% of last personal overdoses, 27% of last witnessed overdoses and 54% of last witnessed fatal overdoses. The particular drugs involved in this "non-opiate" category are detailed in Table 2. These "non-opiate" drugs were most frequently benzodiazepines (more than half of the non-opiate reports in all three categories of overdose)—mainly temazepam or diazepam. Although less frequently, barbiturates also comprised a substantial proportion of reports of "non- opiate" drug use on overdose, being 14% of these reports for both last personal overdose and last witnessed overdose and 12% for last witnessed fatal overdose. Stimulant abuse, particularly cocaine, often co-occurred with opiate abuse in London (as we have reported previously [23,24]) and this was seen with up to 10% of the overdoses-9% of last personal overdoses, 8% of last witnessed overdoses and 6% of last witnessed fatal overdoses.

Discussion

Heroin emerges clearly as the main drug involved in the reported overdoses—more than three-quarters of the personal overdoses of our interviewees, of the overdoses of others which they have witnessed, and also of the fatal overdoses which they have witnessed. Overdoses involving other opiates were much less frequent—less than a quarter as frequent for personal overdoses and witnessed overdoses, and only a third as frequent in witnessed fatal overdoses. Methadone was only occasionally reported as a drug involved in personal overdoses and the witnessed overdoses of others, and was extremely rare as the only drug of overdose (only one of the 117 personal overdoses, three of the 157 witnessed overdoses, and none of the 46 witnessed fatal overdoses).

Fatal overdoses were distinctive in our sample for the greater likelihood of multiple drug involvement compared with the non-fatal overdoses—more than half of the fatal overdoses compared with only a quarter of the non-fatal overdoses. However, the particularly striking feature of this multiple drug use among the fatal overdoses was that it mainly involves a combination of heroin and non-opiate drugs—a combination which accounted for more than a third of all the fatal overdoses while constituting only a quarter of the non-fatal overdoses. Thus, while overdoses of heroin alone were more than twice as frequent as overdoses involving heroin combined with a non- opiate in the non-fatal overdoses (among both the personal overdoses of our interviewees and also the witnessed non-fatal overdoses), the combination of heroin with a non-opiate was just as frequent as a heroin-alone overdose in the fatal overdoses.

The importance of non-opiate drugs as contributors to overdose fatalities has been postulated recently [2527] and our data lend further support to this proposal. While non-opiates alone were an infrequent cause of overdose and only a rare cause of fatal overdose, the combination of opiate with non-opiate drug had not only been a common cause of overdose but was also particularly commonly seen among the overdose fatalities. Among the drugs in the "non-opiate" category, benzodiazepines were particularly commonly reported—more than half of all the reports of "non- opiate" drug use. The dominant position of temazepam presumably not only reflects its substantial share of the prescribing market, but also the large proportion of opiate misusers who also take benzodiazepines [28] and the particular problems of intravenous abuse of temazepam that have occurred in the United Kingdom [29].

The relative frequencies of overdose with either heroin or with methadone and the other pharmaceutical opiates warrant specific consideration in view of the concerns raised by Marks [3] and Newcombe [4,5]. Of "other opiates" (i.e. opiates other than heroin) involved in overdoses, methadone was indeed the opiate most frequently involved—both in conjunction with heroin and also as the only opiate. Of all overdoses in which "other opiates" were involved, methadone had been taken for approximately half of these instances, and this proportion was similar for both the fatal and the non-fatal overdoses. However, these figures were far less than the extent to which heroin was implicated (which was reported approximately 10 times as frequently), although the precise meaning of this figure is difficult to establish as it is itself influenced by the uncertain relative availabilities of heroin and methadone to the population at risk. Furthermore, notwithstanding the consistent finding of good reliability with self-report data from drug misusers [30-33], the actual awareness of earlier drug use contributing to witnessed overdoses must be considered, and hence these data must be considered alongside findings from post-mortem studies as is now being done in Australia [26,34] and the United Kingdom [6].

The frequency with which the different "other opiate" drugs were involved also needs to be considered against the available data on the extent to which they are being prescribed to this population. Data have recently been made available [22] on the extent to which the different opiate drugs are being prescribed. In the national survey of community pharmacies in England and Wales, of data on nearly 4000 opiate prescriptions, 96.0% were for methadone, while Diconal (dipipanone) was only prescribed extremely rarely (0.3%). Thus the important observation with regard to methadone might be considered to be the small number of occasions on which it appears to have been involved in overdoses in view of the wide extent to which it is prescribed to this population, and the interesting observation about Diconal is the frequency with which it is reported in view of the rarity of its prescription.

The contributory significance of alcohol is difficult to gauge from the data collected in our interviews, as these were not constructed in such a way as to explore this area adequately. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that half of the personal overdoses had involved simultaneous intake of alcohol (i.e. on the day of the overdose)—often in large quantities. Others have previously drawn attention to the probable significant interplay of alcohol with opiates in the genesis of adverse outcomes from opiate overdose [33-35] and our data on alcohol consumption, despite their limitations, would support this conclusion.

In conclusion, we find that both fatal and non-fatal overdoses among opiate misusers mostly involve heroin as the drug of overdose (either alone or in

conjunction with a non-opiate drug) and that combined overdoses involving heroin and a non-opiate drug are particularly frequent in the fatal overdoses. For the minority of cases that involve other opiates, methadone is considerably less frequently involved than would be expected in view of its widespread prescription to opiate addicts and the almost universal provision of take-home supplies in the United Kingdom [17]. These data indicate that, at least in this South London context, Marks [3] and Newcombe [4,5] are seriously mistaken when they have concluded that methadone produces greater numbers of fatalities than heroin.

Acknowledgement

These data were collected during the course of a research project supported by the Department of Health. The views expressed are those of the authors.

References

[I] Harding-Pink D. Opioid toxicity-methadone: one person's maintenance dose is another's poison. Lancet 1993;341:665-6.

Obafunwa J, Busuttil A. Deaths from substance overdose in the Lothian and Borders region of Scotland, 1983-1991. Hum Exp Toxicol 1994;13: 401-6.

Marks J. Deaths from methadone and heroin. Lancet 1994;343:976.

Newcombe R. Live and let die: is methadone more likely to kill you than heroin? Druglink 1996;11: 9-12.

Newcombe R. Staying alive: how safe is methadone? Juice 1996;1:16-17.

Cairns A, Roberts I, Benbow E. Characteristics of fatal methadone overdoses in Manchester, 1985-1994. Br Med J 1996;313:264-5.

Kintz P, Mangin P, Lugnier AA, Chaumont AJ. Toxicological data after heroin overdose. Hum Toxicol 1989;8:487-9.

McCarthy JH. More people die from methadone misuse than heroin misuse. Br Med J 1997;315: 603.

Ward J, Mattick RP Hall W, Darke S. The effectiveness and safety of methadone maintenance 1996;91:1727-1728.

[10] Byrne A. A reply to Newcombe (Letter). Addiction 1997;92:220-1.

[1 1] Neeleman J, Farrell M. Fatal methadone and heroin overdoses: time trends in England and Wales. J EpidemiolCommun Health 1997;51:435-7.

Newcombe R. A reply to Ward et al. (Lette Addiction 1996;91.1728-9.

Raistrick D. Substitute prescribing: social policy individual treatment? (and why we must make tl decision). Druglink 1997;12:16-17.

Ward J, Mattick R, Hall W. Key issues in methada maintenance treatment. Sydney: New South \Wal University Press, 1992.

Farrell M, Ward J, Mattick R, et al. Methado: maintenance treatment in opiate dependence: a revieN Br Med J 1994;309:997-1001.

Farrell M, Sell L, Neeleman J, et al. Meth; done provision in the UK. Int J Drug Polk 1996;7:4.

Strang J, Sheridan J, Barber N. Prescribing injectab: and oral methadone to opiate addicts: results from th 1995 national postal survey of community pharmacic in England and Wales. Br Med J 1996;313:270-2.

Powis B, Strang j, Griffiths P, et al. Self-reporte overdose among injecting drug users in Londor extent and nature of the problem. Addiction 1999;9 471-478.

Griffiths P, Gossop M, Powis B, Strang J. Reachin; hidden populations of drug users by the use Privileged Access Interviewers (PAI): report o; methodological and practical issues. Addiction 1993 88:1617-26.

Keubler D,Hausser D. The Swiss hidden populatio: study: practical and methodological aspects of dat. collection by Privileged Access Interviewers. Addictio: 1997;92:325-35.

Strang J, Powis B, Best D, et al. Preventing opiat: overdose fatalities with take-home naloxone: pre launch study of possible impact and acceptability. Addiction 1999;94:199-204.

Sheridan J, Strang J, Barber N, Glanz A. Role o community pharmacies in relation to HIV preventioi and drug misuse: findings from the 1995 nations survey in England and Wales. Br Med J 1996;313 272-4.

Strang J, Griffiths P, Gossop M. Crack and cocain, use in South London drug addicts: 1987-1989. Br Addict 1990;85:193-6.

Marsden J, Griffiths P, Farrell M, Gossop M, Strang] Cocaine in Britain: prevalence, problems and treatmenresponses. J Drug Issues 1998;28: 225-42.

Darke S, Zador D. Fatal heroin "overdose": a review Addiction 1996;91:1765-72.

Darke S, Sunjic S, Zador D, Prolov T. A comparison of blood toxicology of heroin-related deaths and current heroin users in Sydney, Australia. Drug Alcohol Depend 1997;47:45-54.

Frischer M, Goldberg 1), Rahman M, Berney L. Mortality and survival among a cohort of drug injectors in Glasgow, 1982-1994. Addiction 1997;92: 419-28.

Darks S. Benzodiazepine use among injecting drug users: problems and implications. Addiction 1994;89: 379-82.

Strang J, Griffiths P, Abbey J, Gossop M. Survey of use . of injected benzodiazepines by drug users in Britain-1992. Br Med J 1994;308:1082.

Rouse BA,Kozel NJ, Richards LG, eds. Self-report methods of estimating drug use: meeting current challenges to validity 1985. NIDA Research Monograph 57. Rockville, Maryland: National Institute on Drug Abuse, 1985.

Sherman MF Bigelow GE. Validity of patients self-

reported drug use as a function of treatment status. Drug Alcohol Depend 1992;30:1-11.

Anglin MD,Hser I-I, Chou C-P. Reliability and validity of retrospective behavioural self-report by narcotic addicts. Eval Rev 1993;17:91-108.

Darke S. Self-report among injecting drug users: a review. Drug Alcohol Depend 1998;51:253-63.

Zador D, Sunjic S, Darke S. Heroin-related deaths in NSW, 1992: toxicological findings and circumstances. Med J Aust 1996;164:204-7.

Ruttenber A, Kalter H, Santinga P. The role of ethanol abuse in the aetiology of heroin-related deaths. J Forens Sci 1990;35:891-900.